Abstract

Background and Objectives: Drowning is a leading cause of unintentional injury related mortality worldwide, and accounts for roughly 320,000 deaths yearly. Over 90% of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries with inadequate prevention measures. The highest rates of drowning are observed in Africa. The aim of this review is to describe the epidemiology of drowning and identify the risk factors and strategies for prevention of drowning in Africa. Materials and Methods: A review of multiple databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus and Emcare) was conducted from inception of the databases to the 1st of April 2019 to identify studies investigating drowning in Africa. The preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) was utilised. Results: Forty-two articles from 15 countries were included. Twelve articles explored drowning, while in 30 articles, drowning was reported as part of a wider study. The data sources were coronial, central registry, hospital record, sea rescue and self-generated data. Measures used to describe drowning were proportions and rates. There was a huge variation in the proportion and incidence rate of drowning reported by the studies included in the review. The potential risk factors for drowning included young age, male gender, ethnicity, alcohol, access to bodies of water, age and carrying capacity of the boat, weather and summer season. No study evaluated prevention strategies, however, strategies proposed were education, increased supervision and community awareness. Conclusions: There is a need to address the high rate of drowning in Africa. Good epidemiological studies across all African countries are needed to describe the patterns of drowning and understand risk factors. Further research is needed to investigate the risk factors and to evaluate prevention strategies.

Keywords: drowning, immersion injuries, Africa

1. Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines drowning as “the process of experiencing respiratory impairment from either immersion or submersion in liquid” [1]. Drowning is the third leading cause of unintentional injury related cause of mortality worldwide, accounting for 7% of all injury related deaths. It is a global under recognized and neglected public health burden that claims the lives of 320,000 people every year [2]. More than 90% of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries with inadequate prevention measures [3]. It is among the ten leading causes of deaths in children and young people in the world with children aged less than five years at increased risk [4]. Between 1990 and 2013, drowning rates declined by 52.2% globally [5], however, despite this decline, the highest rates of drowning were observed in Africa [3].

The African continent is unfortunately plagued with the world’s most dramatic public health crises with communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, and lower respiratory tract infections as leading causes of death in the region [6]. In addition, there is an increasing burden of non-communicable (hypertension, diabetes and heart) diseases and injuries [6]. The combined burden of both the communicable, non-communicable diseases and injuries have placed a strain on the already weak health systems in addition to struggling economies in the continent [6]. In spite of injuries been identified as a leading cause of death in Africa [4], this public health threat is yet to receive the desired attention, rather the management and prevention of communicable diseases is still a top priority [6].

Africa has recorded considerable success in reducing childhood deaths related to communicable diseases [6]. However, there is limited statistics and data on drowning related deaths which also contributes to infant mortality rates. Age is a leading risk factor for drowning and commonly occurs among children aged 1–4 years [4]. A recent incident that occurred in a West African country, was the case of a thirteen-month-old child who drowned in his parents’ indoor swimming pool [7]. This is a common occurrence in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and within the region [8]. Unfortunately, unlike high-income countries such as Australia and the United States of America (USA), drowning cases and deaths are under-reported in the African continent [4]. Other risk factors of drowning include, male gender, increased access to water, flooding disasters, commuting on water, lack of supervision and recreational drug use [4,9,10].

The knowledge of the epidemiology and risk factors of drowning aids the development and implementation of policies and strategies that reduce the incidence of drowning. Studies originating from high-income countries like Australia and USA suggest a range of primary and secondary prevention strategies to curb drowning deaths [11,12,13,14,15]. Recommendations proposed include increasing supervision, erecting pool fences, increasing public awareness and education through health promotion and public health advocacy [11,12,13,14,15]. However, these interventions may not be applicable in a region like Africa due to the diversity and variation in the epidemiologic, demographic and cultural factors [8].

Currently, there is no systematic review investigating drowning in Africa. Only three recent reviews on drowning in low- and middle-income countries, drowning in South Africa and Tanzania respectively have been published [8,16,17]. Therefore, it is imperative to understand the epidemiology, risk factors and current prevention strategies in Africa to direct policies for the prevention of drowning in Africa. Hence, the aim of this systematic review was to describe the epidemiology of drowning in Africa and to identify the risk factors and proposed and current strategies to prevent drowning.

2. Methods

2.1. Literature Search

The systematic review was conducted in accordance to the preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis guidelines (PRISMA) [18]. The PRISMA flow chart for the review is shown in Supplementary Figure S1. A literature search was conducted using Ovid Medline, Emcare, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), PsycINFO, and Scopus for original research articles published in English from inception until the 30th of November 2018. The search was updated on the 1st April 2019. We included all articles focusing on drowning in Africa. There were slight variations in the search terms depending on the database. Search terms involved a combination of free text words and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms. General search terms were “drown*” and “Africa”. The search strategy for Medline is shown in Supplementary Table S1. The study protocol was registered in PROSPERO with registration number CRD42019092758.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

The studies included in this review are published original research reporting drowning in African countries. We applied no limits to the year of publication and included all age groups. In addition, we included studies that reported drowning as part of other injuries studies to capture all data from the region. Studies excluded were review articles, drowning because of suicide or homicide, non-fatal drowning or near drowning or hospitalization due to drowning or where fatal drowning could not be distinguished from non-fatal drowning.

2.3. Data Extraction

Faith O. Alele (F.O.A.) and Theophilus I. Emeto (T.I.E.) identified all included studies from the search strategy. Uncertainties about the included studies was discussed until consensus was reached. FOA and TIE extracted general and study specific characteristics from the included studies and Lauren Miller (L.M.) and Richard C. Franklin (R.C.F.) crosschecked the data.

2.4. Quality of Methods Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed by FOA and TIE using the modified quality assessment tool for studies with diverse designs (QATSDD) critical appraisal tool [19]. The tool assesses the validity, reliability and generalizability of studies. The included studies were a mix of cross-sectional, descriptive and case-control studies and each study design were assessed using the appraisal tool. The tool was modified to exclude two items that were not applicable to the included studies. The excluded items comprised of statistical assessment of reliability and validity of measurement tool(s) (Quantitative only), fit between stated research question and format and content of data collection tool e.g., interview schedule (Qualitative), assessment of reliability of analytical process (Qualitative only) and evidence of user involvement in design. In the modified QATSDD tool each criterion was awarded a score of 0 to 3 with 0 = not at all, 1 = very slightly, 2 = moderately and 3 = complete. The scores of the criteria were summed up to assess the methodological quality of included studies with a maximum score of 36. For ease of interpretation, the scores were converted to percentages and were categorised as excellent (>80%), good (50–80%) and low (<50%) quality of evidence based on the overall score (Supplementary Table S2).

2.5. Data Synthesis

Drowning was reported exclusively or as part of a wider study such as injury studies. Approximately 28% (11) of the included studies reported drowning as unintentional. In studies where drowning was unspecified, we reported the drowning as intentional. Measures used to report drowning were proportions and incidence rates. The incidence rates and proportions of drowning were reported using frequency tables. The risk factors for drowning were identified in two articles, one of which only reported drowning as part of a wider study. Therefore, the risk factors identified were extrapolated to drowning. However, given the paucity of information on risk factors associated with drowning, we identified the potential risk factors based on previously identified factors documented in the literature [3,4,8] and based on the reported rates of the potential factors. A meta-analysis was not conducted due to the heterogeneity of the included studies.

3. Results

3.1. Epidemiology of Drowning in Africa

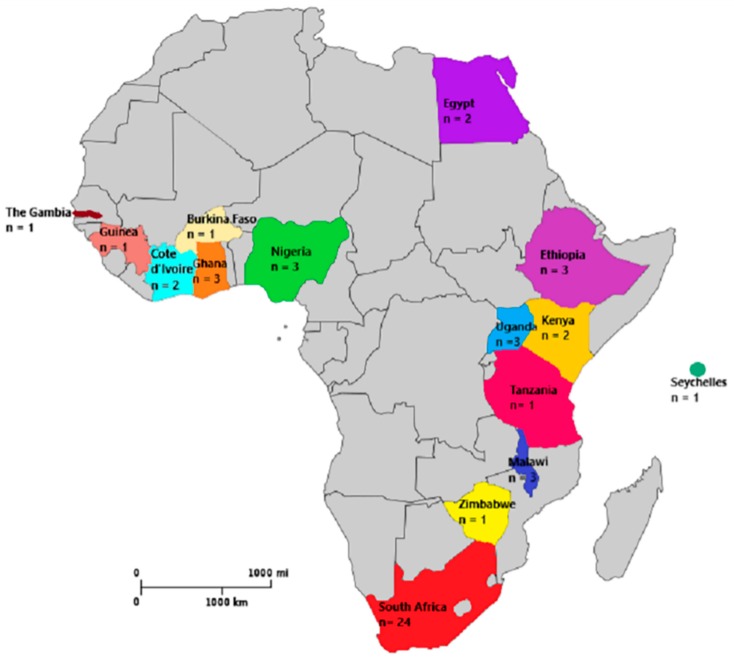

The included studies were conducted across 15 countries in Africa (Figure 1). The databases searches identified 345 articles, of which 42 articles were included in the review after screening for titles, abstracts and full text review (Supplementary Figure S1). Three (3) studies reported drowning in multiple sites (countries) [20,21,22]. Twenty-four (57%) of the articles originated from South Africa [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43], three (7.1%) were from Ethiopia [20,44,45], Ghana [20,46,47], Malawi [20,48,49], Nigeria [50,51,52] and Uganda [53,54,55] respectively, while 2 (4.8%) studies were from Cote d’Ivoire [20,56], Kenya [20,57] and Egypt [21,22] respectively. One (2.4%) article each originated from Burkina Faso [20], Guinea [58], The Gambia [20], Tanzania [59], Seychelles [60] and Zimbabwe [61], See Figure 1 for location. The most commonly used data were surveillance data (46%) and death registers including hospital, police and coronial reports. Twelve (12) studies investigated and described drowning exclusively [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,30,43,50,54,60], while in 30 studies, drowning was reported as part of a wider study including studies investigation all cause of death and external causes of death [20,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,51,52,53,55,56,57,58,59,61]. Measures used to describe drowning were proportions and rates. Drowning rates in children were reported in thirteen (13) studies [21,28,30,31,33,35,37,38,39,42,46,49,52], while 29 (69%) studies described drowning rates of adults and children or adults alone [20,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,32,34,36,40,41,43,44,45,47,48,50,51,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. The denominators used varied by country. In some studies, the estimated proportion or rate of drowning was based on the total population in the study area. By contrast, other studies reported the mortality rates for external causes and all cause of deaths. All deaths due to injuries, trauma and external causes were considered as mortality due to external causes using the ICD 11 classification [62].

Figure 1.

Map of Africa showing the countries and number of studies originating from each country was modified from Wikimedia Commons [63].

3.2. Drowning Rates in Africa

In Table 1, twelve (12) investigated drowning exclusively in different regions of Africa [21,22,23,24,25,26,27,30,43,50,54,60]. However, there were variable methods of reporting drowning across the different studies. Among population-based studies, the proportion of drowning fatalities ranged from 0.019% to 1.2% [23,26]. In studies where all submersion events were reported, unintentional drowning accounted for 80% of drowning deaths in one study [50], while accidental drowning accounted for 10.7% of all submersion (near drowning and drowning) events in another study [30].

Table 1.

Summary of studies exclusively reporting drowning in Africa.

| Authors, Reference, Year | Country | Study Design | Year | Study Population | Rates and Proportion of Drowning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davis and Smith, 1982 [23] | South Africa (Cape Town) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1979–1981 (3 years) | 1,500,000 people (population in Cape Town) | 285 (0.019%) drowning deaths § |

| Grainger 1985 [60] | Seychelles | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1959–1978 (20 years) | 119 drowning deaths | 5.95 ± 2.2 drownings per year (mean drowning rate) |

| Davis and Smith 1985 [24] | South Africa (Cape Town) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1980–1983 (4 years) | 1,600,000 people (population in Cape town) | Male: 38.7/100,000 |

| Female: 8.3/100,000 | |||||

| Meel BL, 2008 [27] | South Africa (Mthatha) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1993–2004 (12 years) | 400,000 people (population in Mthatha) | Mean drowning rate: 7.1/100,000 |

| Seleye-Fubara et al., 2012 [50] | Nigeria (Niger-delta region) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1998–2009 (12 years) | 85 drowning deaths | 80% were unintentional drowning |

| Donson and Nickerk, 2013 [25] | South Africa | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2001–2005 (5 years) | Total population in five cities (Johannesburg, Durban, Cape Town, Port Elizabeth and Pretoria) | 2.1/100,000 |

| Joanknecht et al., 2015 [30] | South Africa: Cape Town | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2007–2013 (6 years) | 75 children admitted for a submersion incident (near drowning and drowning) | 10.7% of the study population drowned |

| Lin et al., 2015 [22] | Egypt South Africa |

Ecological study | 2009–2011 (3 years) 2007–2009 (3 years) |

Entire population in the country Entire population in the country |

1.5/100,000 2.5/100,000 |

| Morris et al., 2016 [26] | South Africa (Pretoria) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2002–2011 | 23,050 registered deaths 278 deaths due to external causes |

1.2% (278) of the deaths were due to drowning |

| Kobusingye et al., 2017 [54] ‡ | Uganda (Buikwe; Kampala; Mukono; Wakiso) | Mixed methods: Quantitative—Cross-sectional ǂ |

Not stated | 2804 people (population in the community) | 502/100,000 |

| Wu et al., 2017 [21] | Egypt South Africa |

Ecological study | 2000 and 2013 | WHO world standard population WHO world standard population |

Unintentional drowning rate 2000: 3.89/100,000 2013: 2.93/100,000 2000: 0.33/100,000 2013: 3.38/100,000 |

| Saunders et al., 2018 [43] | South Africa (Western Cape) | Descriptive cross-sectional | 2010–2016 (6 years) | Total population in Western Cape (not stated by the authors) | 3.2/100,000 |

§ Drowning proportions was calculated using data provided in the article. ‡ For the purpose of the review, only the quantitative aspect of the study was included in the review.

The incidence rates of drowning across the different studies ranged from a low of 0.33/100,000 population to a high of 502/100,000 population [21,22,24,25,27,43,54]. However, the denominators for each study varied. Two studies were conducted using the total population in the country as the denominator [21,22], five studies were conducted within specific cities and towns and total population of the cities were used as denominators [23,24,27,43,54], while one study investigated drowning across five cities [25].

Of the 30 studies reporting drowning as part of a wider study (Table 2), 25 studies reported drowning as part of external cause of death (injury) [20,28,29,31,32,33,34,35,36,40,41,42,44,45,46,47,48,49,51,52,53,55,57,58,59], while 5 studies investigated all causes of deaths and reported the rates of drowning [37,38,39,45,56]. The studies investigating external causes of deaths reported drowning deaths either as a proportion [28,29,31,32,33,34,40,41,42,44,46,47,49,51,52,55,57,61] or as a rate [20,35,36,48,53,58,59] of all external causes of deaths. The proportion of drowning deaths as part of external causes of death ranged from 0.2% to 75% [28,29,31,32,33,34,40,41,42,44,46,47,49,51,52,55,57,61] while the incidence rate ranged from 2.1/100,000 to 10.2/100,000 [35,36,48,58,59]. One ecological study which investigated external causes of deaths across eight (8) countries reported drowning rates ranging from 0/1000 person years to 0.48/1000 person years [20], while. Lett et al., reported that drowning rate account for 0.1/1000 people of all external cause of deaths [53]. In studies reporting drowning as a part of all causes of deaths, the proportion of drowning deaths ranged from 0.02% to 11% [37,38,39,45,56].

Table 2.

Studies describing drowning as part of other studies (including external causes and all causes) in Africa.

| Authors, Reference, Year | Country | Study Design | Year | Study Population | Rates and Proportion of Drowning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitiyo 1974 [61] | Zimbabwe (Bulawayo area) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1972 | 188 adult deaths (external causes) | 11.17% (21) drowning deaths |

| Knobel et al., 1984 [28] | South Africa | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1966–1981 (15 years) | 3248 children < 15 years (external causes) | 356 drowning deaths (11%) |

| Kibel et al., 1990 [31] | South Africa | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1981–1985 (5 years) | 14,118 children under 15 years of age (deaths due to external causes) | 19% of all injury related deaths |

| Flisher et al., 1992 [42] | South Africa | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1984–1986 (3 years) | 9288 adolescent deaths due to external causes | 10.8% of all deaths due to external causes |

| Lerer et al., 1997 [32] | South Africa (Cape Town) | Descriptive cross-sectional | 1994 (1 year) | 3690 deaths due to external causes | 2.6% (96) of all non-natural mortality was due to drowning |

| Kobusingye et al., 2001 [55] | Uganda (Mukono district) | Descriptive cross-sectional | 1993–1998 (5 years) | 34 fatal injuries (external causes) | 27% (9) of fatal injuries were due to drowning |

| Moshiro et al., 2001 [59] | Tanzania | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1992–1998 (6 years) | 64,756 persons in Dr es Salaam | Overall drowning incidence not stated |

| 146,359 (population in Hai) | Female drowning rates/100,000 | ||||

| 103,053 (population in Morogoro) | Dar es Salaam: 4.7 | ||||

| 1478 deaths due to injuries (external causes) all age groups | Hai District: 5.5 | ||||

| Morogoro: 5.1 | |||||

| Male drowning rates/ 100,000 | |||||

| Dar es Salaam: 9.2 | |||||

| Hai District: 10.2 | |||||

| Morogoro: 7.9 | |||||

| Lett et al., 2006 [53] | Uganda (Gulu district) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 1994–1999 (5years) | 8595 people397 deaths due to external causes | 0.1/1000 people were due to drowning |

| Osime et al., 2007 [51] | Nigeria (Benin City) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2001–2004 (4 years) | 5446 trauma related deaths (external causes) | Drowning accounted for 0.8% of all trauma related deaths |

| Burrows et al., 2010 [35] | South Africa | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2001–2003 (2 years) | 3,301,190 children aged 0–14 years 2923 injury related deaths (external causes) of children aged 0–14 years |

Female: 2.1/100,000 |

| Male: 5.3/100,000 | |||||

| Ohene et al., 2010 [46] | Ghana (Accra) | Descriptive cross-sectional | 2001–203 (2 years) | 151 injury related deaths (external causes) among adolescents aged 10–19 years | 38% of deaths were due to drowning |

| Garrib et al., 2011 [40] | South Africa | Analytical cross-sectional | 2000–2007 (7 years) | 133,483 people 1022 injury related deaths (external causes) |

3.3% due to drowning |

| Mendes et al., 2011 [29] | South Africa (Johannesburg) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2006–2009 (4 years) | 1760 unintentional injuries (external causes) | 0.34% of the deaths were due to drowning § |

| Mamady et al., 2012 [58] | Guinea | Analytical cross-sectional study | 2007 | 9,710,144 (total population) 7066 fatal injuries (external causes) |

4.4/100,000 |

| Odhiambo et al., 2013 [57] | Kenya | Analytical cross-sectional | 2003–2008 (5 years) | 220,000 people (total population) 11,147 adult deaths due to trauma (external causes) |

0.2% (23) deaths were due to drowning |

| Weldearegawi et al., 2013 [45] | Ethiopia (Kilite Awlaelo surveillance site) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2009–2011 (3 years) | 409 deaths (all causes) | 4.6% of all deaths were due to drowning |

| Streatfield et al., 2014 [20] | Burkina Faso Cote d’Ivoire Ethiopia The Gambia Ghana Kenya Malawi South Africa |

Ecological study | 2000-2012 (3 years) | 111,910 deaths/ 12,204,043 person-years across Africa and Asia due to external causes | Rates/1000 person years Burkina Faso (Nouna): 0.00 Burkina Faso (Ouagadougou): 0.20 Cote d’Ivoire (Taabo): 0.14 Ethiopia (Kilite Awlaelo): 0.13 The Gambia (Farafenni): 0.11 Ghana (Dodowa): 0.28 Ghana (Navrongo): 0.48 Kenya (Kilifi): 0.18 Kenya (Kisumu): 0.22 Kenya (Nairobi): 0.18 Malawi (Karonga): 0.19 South Africa (Africa Centre): 0.19 South Africa (Agincourt): 0.07 |

| Chasimpha et al., 2015 [48] | Malawi (Karonga district) | Nested case-control | 2002 2012 | 59,947 people (children and adults) in Karonga districtDeaths due to external causes | Unintentional drowning rate: 8.6/100,000 |

| Kone et al., 2015 [56] | Cote d’Ivoire | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2009–2011 (3 years) | 39,422 people (total population)712 deaths (all causes) | Unintentional drowning rates |

| Male * | |||||

| 5–14: 0.1% | |||||

| 15–49: 0.3% | |||||

| Female * | |||||

| 5–14 years: 0.02% | |||||

| Matzopoulos et al., 2015 [36] | South Africa | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2009 | 52,493 injury related deaths (external causes) | Unintentional drowning3.3/100,000 |

| Olatunya et al., 2015 [52] | Nigeria (Ekiti State) | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2012–2014 (2 years) | 5264 children admitted for injury related incidents (external causes) | Drowning accounted for 4.54% of all injuries |

| Pretorius and Niekerk, 2015 [33] | South Africa: Guateng | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2008–2011 (2 years) | Total population in Gauteng 5404 fatal injuries (external causes) in children aged 0–19 years |

8.9% of all fatal injuries were due to drowning |

| Groenewald et al., 2016 [38] | South Africa: Western Cape | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2011 | 2412 deaths (all causes) of children under 5 years of age | Drowning accounted for 2.8% of all deaths |

| Mathews et al., 2016 [37] | South Africa: Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2014 | 711 child deaths (all causes) | Drowning deaths accounted for 2.5% of all deaths |

| Reid et al., 2016 [39] | South Africa: Western Cape | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2011 | 180,814 children under 5 years of age (total population) 1051 under-5 deaths (all causes) |

11% of all deaths were due to drowning |

| Meel BL, 2017 [34] | South Africa | Descriptive epidemiology | 1996–2015 (20 years) | 24, 693 deaths due to unnatural (external) causes | 5.1% of unnatural deaths were due to drowning |

| Purcell et al., 2017 [49] | Malawi: Lilongwe | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2008–2013 (6 years) | 30,462 children with traumatic injuries 343 deaths due to external causes |

11.4% of the deaths were due to drowning |

| Erasmus et al., 2018 [41] | South Africa | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2010–2014 (5 years) | 184 injuries related (external causes) deaths over the time period | 75% (138) of the deaths were due to drowning |

| Gelaye et al., 2018 [44] | Ethiopia | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2009–2013 (5 years) | 623 injury related deaths (external causes) | 21.8% (136) deaths were due to drowning |

| Ossei et al., 2019 [47] | Ghana | Descriptive cross-sectional study | 2008–2016 (8 years) | 1470 unnatural deaths (external causes) | 7.14% of the deaths were due to drowning |

§ Drowning proportions were calculated using data provided in the articles. * Other age groups reported no drowning deaths.

In terms of drowning rates by age demographics, the proportion of drowning among children and adolescents ranged from 2.5% to 19% [28,30,31,33,37,38,39,42,46,49,52], while the incidence of drowning ranged from 0.33 to 5.3 per 100,000 population [21,35]. The rates of drowning among adults ranged from 0.33 to 502 per 100,000 population [22,24,25,27,36,48,54,59] and from 0 to 0.07 per 1000 person years [20,53]. In addition, the proportion of drowning among adults ranged from 0.019% to 80% [23,26,29,32,34,40,41,44,45,50,51,55,56,57,58,60,61].

3.3. Potential Risk Factors

In Table 3, only two studies reported risk factors [48,58]. One study identified risk factors associated with drowning [58] and the other study reported risk factors of a wider study [58]. The identified risk factors were being a fisherman [58], having fishing as source of income [58], being male [58] and older age with the odds of drowning increasing with increasing age from 2.0 to 8.9 [58]. Potential risk factors were identified in 26 studies based on the rates of drowning reported and these potential factors include age, gender, ethnicity, alcohol, access to bodies of water, age of boat and carrying capacity of the boat, weather and summer season. In 19 studies, age was identified as a potential risk factor [24,25,26,27,28,30,31,32,33,37,40,42,46,47,55,57,58,59,60], with 13 studies reporting higher rates of drowning among children and adolescents [25,27,28,30,31,32,33,37,42,43,46,47,59]. In addition, males were reported to have higher rates of drowning compared to females in 15 studies [24,25,26,27,28,35,36,40,43,45,46,47,57,58,60]. Furthermore, six studies reported the rates of drowning for different races [24,26,28,31,35,42]. However, race as a potential risk factor varied between the included studies with three studies classifying the race by age groups [24,31,42]. The other three studies reported the rates of drowning for all age groups without grouping them [26,28,35]. Among studies reporting drowning rates for race by age groups, children aged <1 year–5 years of white African ethnicity were most vulnerable to drowning compared to other races. By contrast, drowning was more prevalent in adolescents and adults of black African ethnicity and Asian ethnicity [24,31,42}. Where no age classification was used, blacks of African ethnicity were reportedly had higher drowning rates in two studies [26,35], while one study reported a higher rate of drowning among whites of African ethnicity [28]. Other potential risk factors identified were alcohol [23,25,26], summer season [24,26,28,42,43], boat age and overloading of the boat [64], stormy weather [64] and access to bodies of water [24,25,26,31,43,48,54,55].

Table 3.

Studies discussing potential risk factors for drowning among all age groups in Africa.

| Authors, Reference, Year | Country | Study Population | Proportions or Rates of Potential Risk Factors | Potential Risk Factors/Risk Factors Identified | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davis and Smith, 1982 [33] | South Africa (Cape Town) | 1,500,000 people | Alcohol | ||||

| Knobel et al., 1984 [28] | South Africa | 3248 children < 15 years | Race | Race: whites | |||

| Coloured | 10.7% | ||||||

| White | 16.1% | ||||||

| Black | 7.9% | ||||||

| Gender | Male | ||||||

| Male | 11.7% | ||||||

| Female | 9.7% | ||||||

| Age | |||||||

| <1 year | 6.9% | Age: 6–14 | |||||

| 1–5 years | 12.8% | ||||||

| 6–14 years | 20.3% | Summer season | |||||

| Weekends | |||||||

| Davis and Smith 1985 [24] | South Africa (Cape Town) | 1,600,000 people | Race | Race: Black race for adults >30 years | |||

| Black race | 32.3/100,000 | White race for children 0–5 years | |||||

| Colored | 24.2/100,000 | Male | |||||

| White | 13.4/100,000 | ||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 38.7/100,000 | ||||||

| Female | 8.3/100,000 | ||||||

| Age | Age: 21–30 | ||||||

| 0–5 years | 13.3% | ||||||

| 6–10 years | 5.8% | ||||||

| 11–15 years | 4.9% | ||||||

| 16–20 years | 10.98% | ||||||

| 21–30 years | 25.14% | Summer season | |||||

| 31–40 years | 15.61% | Swimming pools | |||||

| >40 years | 24.28% | Alcohol | |||||

| Grainger 1985 [60] | Seychelles | 119 drowning deaths | Age | Age: 40–49 years | |||

| 0–9 years | 6.72% | Epilepsy | |||||

| 10–19 years | 13.44% | Head injury | |||||

| 20–29 years | 16.8% | Time of day: 12–2 pm | |||||

| 30–39 years | 18.5% | ||||||

| 40–49 years | 21.8% | ||||||

| 50–59 years | 12.6% | ||||||

| 60–69 years | 5.88% | ||||||

| 70+ years | 4.2% | ||||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 109 deaths | Male | |||||

| Female | 10 deaths | ||||||

| Kibel et al., 1990 [31] | South Africa | 14,118 children under 15 years of age (injuries related death) | Age | Age: 1–4 years | |||

| <1year | 7.4% | ||||||

| 1–4 years | 23.0% | ||||||

| 5–14 years | 20.1% | ||||||

| Race | <1 year | White race for children <1 year to 4 years | |||||

| Blacks | 6.7% | Black race for children aged 5–14 years | |||||

| Whites | 9.5% | Site: | |||||

| Coloured | 8.3% | Swimming pools for white children | |||||

| Asians | 6.4% | Dams and rivers for older black children | |||||

| 1–4 years | |||||||

| Blacks | 18.8% | ||||||

| Whites | 42.7% | ||||||

| Coloured | 22.1% | ||||||

| Asians | 9.4% | ||||||

| 5–14 years | |||||||

| Blacks | 21.9% | ||||||

| Whites | 12.7% | ||||||

| Coloured | 21.2% | ||||||

| Asians | 9.4% | ||||||

| Flisher et al., 1992 [42] | South Africa | 9288 adolescent deaths due to external causes | Race | 10–14 years | Age: 10–14 years | ||

| Whites | 6.3% | Black race for adolescents 10–14 years old | |||||

| Coloured | 25.2% | Asian race for adolescents 15–19 years old | |||||

| Asians | 12.7% | Summer season | |||||

| Black | 24.2% | ||||||

| Race | 15–19 years | ||||||

| Whites | 4.2% | ||||||

| Coloured | 9.7% | ||||||

| Asians | 12.5% | ||||||

| Black | 6.3% | ||||||

| Lerer et al., 1997 [32] | South Africa (Cape Town) | 3690 non-natural mortality | Age | Number of drowning deaths | Age: 0–14 years | ||

| 0–14 years: | 35 | ||||||

| 15–24 years: | 10 | ||||||

| 25–34 years | 16 | ||||||

| 35–44 years | 16 | ||||||

| 45–54 years | 12 | ||||||

| 55–64 years | 3 | ||||||

| 65–74 years | 1 | ||||||

| 75+ years | 3 | ||||||

| Kobusingye et al., 2001 [55] | Uganda (Mukono district) | 34 fatal injuries | Age | % of drowning | Age: 10–39 years | ||

| <10 years | 0% | Extensive water surface | |||||

| 10–19 years | 18% | ||||||

| 20–29 years | 18% | ||||||

| 30–39 years | 18% | ||||||

| 40–49 years | 0% | ||||||

| >50 years | 0% | ||||||

| Moshiro et al., 2001 [59] | Tanzania | 1478 deaths due to injuries all age groups | Female gender/100,000 population | Females; | |||

| Dar es Salaam | Hai District | Morogoro | 0–4 years (across the three districts) | ||||

| 0–4 years | 7.0 | 17.1 | 6.9 | ||||

| 5–14 years | 2.2 | 5.0 | 6.0 | Males: | |||

| 15–59 years | 5.2 | 3.0 | 4.2 | Dar es Salaam: 15–59 years | |||

| 60+ years | 2.8 | 4.6 | Hai District: 0–4 years | ||||

| Morogoro: 60 years and above | |||||||

| Male gender/100,000 population | |||||||

| Dar es Salaam | Hai District | Morogoro | |||||

| 0–4 years | 3.4 | 12.3 | 12.1 | ||||

| 5–14 years | 4.9 | 9.0 | 3.6 | ||||

| 15–59 years | 12.4 | 10.6 | 7.9 | ||||

| 60+ years | 8.5 | 16.1 | |||||

| Meel BL, 2008 [27] | South Africa (Mthatha) | 405 drowning deaths | Male | Female | Male | ||

| 1–10 years | 23.4% | 6.9% | Age: 1–20 years | ||||

| 11–20 years | 15.2% | 9.2% | |||||

| 21–30 years | 9.8% | 4.7% | |||||

| 31–40 years | 11.3% | 2.8% | |||||

| 41–50 years | 5.0% | 1.3% | |||||

| 51–60 years | 3.8% | 0.6% | |||||

| 61+ years | 3.1% | 2.5% | |||||

| Burrows et al., 2010 [35] | South Africa | 2923 injury deaths of children aged 0–14 years | Drowning rate per 100,000 | ||||

| Gender | |||||||

| Female | 2.1 | Buffalo City | |||||

| Male | 5.3 | ||||||

| Male | |||||||

| Population group | |||||||

| Asian | 0.9 | ||||||

| White | 4.3 | ||||||

| Coloured | 2.0 | ||||||

| African | 4.3 | African | |||||

| City | |||||||

| Tshwane | 2.9 | ||||||

| Cape Town | 2.2 | ||||||

| Johannesburg | 4.2 | ||||||

| eThekwini | 3.8 | ||||||

| Nelson Mandela | 3.7 | ||||||

| Buffalo City | 9.2 | ||||||

| Ohene et al., 2010 [46] | Ghana (Accra) | 151 injury related deaths among adolescents aged 10–19 years | Gender | Male | |||

| Female | 25% | ||||||

| Male | 44% | ||||||

| Age | |||||||

| 10–14 years | 46% | Age: 10–14 years | |||||

| 15–19 years | 33% | ||||||

| Garrib et al., 2011 [40] | South Africa | 1022 injury related deaths | Age | Children aged 0–15 years | |||

| 0–15 years | 65% | ||||||

| >15 years | 35% | ||||||

| Gender (rate/100,000 person years) | |||||||

| Male | 6.2 | Male | |||||

| Female | 3.4 | ||||||

| Mamady et al., 2012 [58] | Guinea | 7066 fatal injuries | Female | Ref | |||

| Male | OR 2.8; 95% CI (2.3–3.5) | ||||||

| 0–4 years | Ref | ||||||

| 5–14 years | OR 2.0; 95% CI (1.1–3.5) | ||||||

| 15–24 years | OR 8.9; 95% CI (5.3–15.0) | ||||||

| 25–64 years | OR 7.0; 95% CI (4.2–11.7) | ||||||

| 65+ years | OR 7.9; 95% CI (4.4–14.3) | ||||||

| Seleye-Fubara et al., 2012 [50] | Nigeria (Niger-delta region) | 85 drowning deaths | Alcohol | ||||

| Hard drugs | |||||||

| Epilepsy | |||||||

| Donson and Nickerk, 2013 [25] | South Africa | 1648 drowning deaths | Age (rate/100,000) | ||||

| 0–4 years | 6.3 | 0–4-year age group | |||||

| 5–14 years | 2.2 | ||||||

| 15–29 years | 1.7 | Swimming pools | |||||

| 30–44 years | 1.8 | ||||||

| 45–59 years | 1.4 | Alcohol use | |||||

| 60+ years | 1.2 | ||||||

| Gender (rate/100,000) | December | ||||||

| Male | 3.4 | ||||||

| Female | 0.9 | Male | |||||

| Odhiambo et al., 2013 [57] | Kenya | 11,147 adult deaths due to trauma | Gender | ||||

| Female | 13% | Male | |||||

| Male | 87% | ||||||

| Age | |||||||

| <40 years | 83% | Young adults (<40 years of age) | |||||

| >40 years | 17% | ||||||

| Weldearegawi et al., 2013 [45] | Ethiopia (Kilite Awlaelo surveillance site) | 409 deceased | Gender | Male | |||

| Female | 1.7% | ||||||

| Male | 2.9% | ||||||

| Chasimpha et al., 2015 [48] | Malawi (Karonga district) | 59,947 people (children and adults) in Karonga district | Children from fishing households | OR 3.07; 95% CI (1.03–9.10) ‡ | |||

| Adult male with fishing as a source of income | OR 2.45; 95% CI (1.17–5.14) ‡ | ||||||

| Adult males who are fishermen | OR 2.92; 95% CI (1.42–5.98) ‡ | ||||||

| Adult females who have other occupations | OR 4.04; 95% CI (1.22–13.4) ‡ | ||||||

| Joanknecht et al., 2015 [30] | South Africa (Cape Town) | 75 children admitted for a submersion incident | Public pools and the ocean for children older than 5 years of age | ||||

| Private pools, baths and buckets for children less than 5 years | |||||||

| Matzopoulos et al., 2015 [36] | South Africa | 52,493 injury related deaths | Gender (rate/100,000 population) | Male | |||

| Female | 1.2 | ||||||

| Male | 5.7 | ||||||

| Pretorius and Niekerk, 2015 [33] | South Africa (Guateng) | 5404 fatal injuries in children aged 0–19 years | Age | ||||

| 0–1 year | 9.4% | Age: 2–3 years | |||||

| 13.4% | 2–3 years | 16.8% | |||||

| 4–6 years | 13..4% | ||||||

| 7–12 years | 13.1% | ||||||

| 13–19 years | 3.0% | ||||||

| Mathews et al., 2016 [37] | South Africa (Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal) | 711 child deaths | Age | ||||

| <1 year | 1.1% | Age: 1–4 years | |||||

| 1–4 years | 5.8% | ||||||

| 5–14 years | 5.0% | ||||||

| 15–17 years | 1.9% | ||||||

| Morris et al., 2016 [26] | South Africa (Pretoria) | 346 deaths due to external causes | Gender | ||||

| Female | 21% | Male | |||||

| Male | 79% | ||||||

| Race | |||||||

| Black | 71% | Black race | |||||

| White | 24% | ||||||

| Coloured | 4% | ||||||

| Asian | 1% | ||||||

| Age | Age >18 years | ||||||

| <1 year | 15% | ||||||

| 1–2 years | 19% | Summer months (December to February) | |||||

| 2–13 years | 18% | Alcohol | |||||

| 13–18 years | 3% | Swimming pool | |||||

| >18 years | 45% | ||||||

| Kobusingye et al., 2017 [54] | Uganda (Buikwe; Kampala; Mukono; Wakiso) | 2804 people (population in the community) | Access to water bodies (for transportation or fishing) | ||||

| Overloading | |||||||

| Stormy weather | |||||||

| Old age of boats | |||||||

| Meel BL, 2017 [34] | South Africa | 24,693 deaths due to unnatural causes | Gender | Female | |||

| Female | 6.07% | ||||||

| Male | 4.8% | ||||||

| Gelaye et al., 2018 [44] | Ethiopia | 623 injury related deaths | Gender | Female | |||

| Female | 22% | No formal education (illiterates) | |||||

| Male | 21.1% | ||||||

| Saunders et al., 2018 [43] | South Africa (Western Cape) | 1391 drowning deaths | Age (rate/100,000 population) | Age: 0–19 years | |||

| Children (0–19 years) | 3.8 | ||||||

| Adults (20+ years) | 3.0 | ||||||

| Gender (rate /100,000 population) | |||||||

| Female | 1.2 | Male | |||||

| Male | 5.3 | Access to large open bodies of water | |||||

| Summer season (December, January, February) | |||||||

| Ossei et al., 2019 [47] | Ghana | 1470 unnatural deaths | Age | Age: 0–9 years | |||

| ≤9 years | 40% | ||||||

| 10–19 years | 17.14% | ||||||

| 20–29 years | 17.14% | ||||||

| 30–39 years | 10.48% | ||||||

| 40–49 years | 6.67% | ||||||

| 50–59 years | 3.81% | ||||||

| 60–69 years | 2.86% | ||||||

| ≥70 years | 1.90% | ||||||

| Gender | Male | ||||||

| Female | 22.9% | ||||||

| Male | 77.1% | ||||||

‡ Risk factors for external death, which also applies to drowning.

3.4. Prevention Strategies

Sixteen (16) studies proposed prevention strategies to reduce drowning rates in Africa [23,24,25,26,27,30,31,42,44,45,46,48,53,54,59,60]. These prevention strategies include increased supervision of children around bodies of water, aquatic education and training about basic life support measures, training about life skills in communities, community awareness and implementation of legislation to prevent drowning (Table 4). Using the hierarchy of controls [64], fourteen of the sixteen studies proposed administrative control/preventive measures, which included education/training on basic life support, legislative laws and increasing public awareness [23,25,27,30,31,42,44,45,46,48,53,54,59,60]. Two studies proposed engineering control measure that include building life safety facilities and the use of barriers and safety nets around swimming pools [24,26].

Table 4.

Studies discussing proposed prevention strategies for drowning among all age groups in Africa.

| Authors, Reference, Year | Country | Study Population | Prevention Strategy | Hierarchy of Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davis and Smith, 1982 [23] | South Africa (Cape Town) | 1,500,000 people | Increase public awareness | Administrative control |

| Media campaign to reduce drinking in combination with aquatic activities | ||||

| Davis and Smith 1985 [24] | South Africa (Cape Town) | 1,600,000 people | Live saving facilities | Engineering control |

| Improved adult supervision of children | Administrative control | |||

| Grainger 1985 [60] | Seychelles | 165 deaths due to accidents | Primary health education proposed | |

| 119 drowning deaths | ||||

| Kibel et al., 1990 [31] | South Africa | 14,118 children under 15 years of age | Increase public awareness | Administrative control |

| Safety legislation to reduce environment hazards | Administrative control | |||

| Flisher et al., 1992 [42] | South Africa | 9288 adolescent deaths | Media efforts/ intervention to prevent drowning | Administrative control |

| Moshiro et al., 2001 [59] | Tanzania | 1478 deaths due to injuries | Education | Administrative control |

| Lett et al., 2006 [53] | Uganda (Gulu district) | 397 deaths due to injuries associated with war | Formal monitoring by international bodies with no political or economic interest in the conflict. | Administrative control |

| Meel BL, 2008 [27] | South Africa (Mthatha) | 405 drowning deaths | Education and training at schools about life skills | Administrative control |

| Ohene et al., 2010 [46] | Ghana (Accra) | 151 deaths among adolescents aged 10–19 years | Aquatic safety education | Administrative control |

| Supervision near recreational water bodies | Administrative control | |||

| Donson and Nickerk, 2013 [25] | South Africa | 1648 drowning deaths | Public aquatic safety education | Administrative control |

| Implementation of evidence-led safety measures | Administrative control | |||

| Water safety legislation | Administrative control | |||

| Weldearegawi et al., 2013 [45] | Ethiopia (Kilite Awlaelo surveillance site) | 409 deceased | Integrating occupational and safety education with existing health programme to reduce mortalities associated with accidents | Administrative control |

| Chasimpha et al., 2015 [48] | Malawi (Karonga district) | 59,947 people (children and adults) | Improved supervision of children around bodies of water | Administrative control |

| Joanknecht et al., 2015 [30] | South Africa (Cape Town) | 75 children admitted for a submersion incident | Community based education and prevention programs focusing on restricting access to private pools for young children | Administrative control |

| Morris et al., 2016 [26] | South Africa (Pretoria) | 346 deaths due to external causes | Public education regarding basic life support measures and dangers of alcohol consumption and swimming | Administrative control |

| Use of safety nets/barriers | Engineering control | |||

| Kobusingye et al., 2017 [54] | Uganda (Buikwe; Kampala; Mukono; Wakiso) | 2804 people | Enforce boat construction and maintenance regulations | Administrative control |

| Loading limits | Administrative control | |||

| Boat crew training | Administrative control | |||

| Use of weather forecast | Administrative control | |||

| Gelaye et al., 2018 [44] | Ethiopia | 623 injury related deaths | Community awareness | Administrative control |

3.5. Methodological Quality Assessment

The QATSDD scores ranged from 53% to 100% (Supplementary Table S1). Thirty-three studies which scored above 80% [20,21,22,25,26,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59], were categorised as having excellent methodological quality, and included details about sampling, data analysis, strengths and limitations of the study. The other studies were considered to be of good methodological quality [23,24,27,28,42,50,51,60,61] and no study scored below 50%. The included studies utilised retrospective data or collected information retrospectively from participants. Inaccuracy and incompleteness of the data may be associated with the use of retrospective data. In addition, misclassification bias may have been introduced into the studies that used retrospective data. Furthermore, depending on the participants, recall bias may have been introduced into some of the studies. These biases could have underestimated or overestimated the burden of drowning in Africa.

4. Discussion

Drowning is a significant public health burden in Africa and the findings of this systematic review suggest that there is a huge variation in drowning mortality across Africa. The highest proportion of drowning (approximately 80%) was reported in Nigeria [50], while the highest rate reported (502/100,000 population) was observed in Uganda [54]. Although only two studies identified risk factors which includes being a fisherman, and older age [48,58]; we identified potential risk factors based on previous evidence [3]. The limited evidence suggests that male gender and young people are at higher risk for drowning especially children and adolescents. In addition, other potential risk factors identified were being of black African ethnicity, alcohol use, access to bodies of water, age of boat and carrying capacity of the boat, weather and summer season. This systematic review has highlighted the need for more data on drowning prevalence, together with good epidemiological studies across all African countries to describe the patterns of drowning and understand risk factors to guide prevention initiatives.

Due to the limited data available, quantifying the prevalence of drowning in Africa was challenging. This finding was echoed in a study of drowning in low- and middle-income countries by Tyler et al. who reported that inconsistences in data collection for drowning poses as a challenge for data synthesis [8]. Although the estimated rates and proportions may be considered high, in majority of the studies, drowning was reported as part of a wider injury study. Of the 54 countries in Africa, only 15 countries had some published data on drowning with the majority (57%) of the literature originating from South Africa. In many African countries, cases go unreported and the lack of an injury surveillance system as seen in many LMIC also contributes to the limited data [65]. This is consistent with the findings of two recent systematic reviews describing the burden of drowning in South Africa and Tanzania [16,17]. Saunders et al. and Sarrassat et al., reported that strengthening the existing surveillance systems or establishing new ones are needed for consistent and detailed drowning surveillance [16,17]. In addition, as many of the drowning cases result in death at the time of the event, only a small proportion present at the hospital or medical facilities [66]. Both the lack of the injury surveillance system and underreporting of drowning cases prevent accurate documentation of drowning mortality in health records. According to WHO, approximately 90% of global drowning deaths occur in LMICs. Africa as a region had an estimated 73,635 drowning deaths in 2016 which accounted for approximately 23% of the total drowning deaths globally [67]. However, data collection in the region is limited, and hence the statistics from Africa underrepresents the true burden of drowning in the region [4].

Many of the potential risk factors associated with drowning identified in this review are similar to those reported in previous systematic reviews. Drowning occurred more frequently in males between the ages of 0 to 15 years. Specifically, highest drowning occurrences were found in the 0–5-year age group. In LMICs, drowning rates among children were higher among children aged 1–4 years, followed by children aged 5–9 years with males being twice as likely as females to drown [8]. In addition, younger children were found to drown in private pools or baths, whereas older children were found to drown in public swimming pools, rivers, dams or in the ocean. Given that a majority of the studies originated from South Africa, drowning in swimming pools occurred more in white African children, whereas drowning in dams and rivers were found to occur in older black African children [24,31]. Although it is not evident that socioeconomic status is a potential risk factor in this review, children from low-income households may not have access to private swimming pools and are more likely to access natural bodies of water around the house as reported in other LMICs [8]. Evidence suggests that a lack of child supervision and the lack of safety barriers has been associated with high drowning rates among children [66]. Furthermore, access to other water bodies using boats or through fishing, depending on occupational or recreational purposes was also considered as a potential risk factor [48,54]. Specifically, children and adults from fishing households, are more likely to access these types of water bodies daily, requiring significant surveillance and awareness strategies for children in such settings. Other potential risk factors such as alcohol consumption has been shown to be associated with drowning especially among adolescents and adult [68]. As blood alcohol concentration level rises, judgement, balance and vision may be impaired, increasing the risk of drowning. Binge drinking is common in some African countries and has been reported to be associated with drowning among adult men [23,24,25,26,50]. This calls for increased awareness of the risk of alcohol consumption in conjunction with swimming.

The prevention strategies proposed by sixteen studies includes focusing on pool safety such as restricting access to private pools for young children, education and training at schools on life skills, increasing public awareness through media campaigns, and the implementation of water safety legislation, community awareness, improved supervision of children around water bodies, building lifesaving facilities and enforcement of boat construction and maintenance regulations. Using the hierarchy of controls which is a system used to minimize or eliminate hazards [64], only two studies proposed engineering controls as a way of preventing drowning [24,26]. All other studies proposed prevention strategies that require administrative controls which is the least effective way to prevent drowning [23,25,27,30,31,42,44,45,46,48,53,54,59,60]. However, prevention interventions and methods may not be consistent between countries due to the diversity and variation in their epidemiology, demographic and cultural characteristics [8]. There is no simple solution to addressing the burden of drowning in all countries, therefore strategies would have to be designed specifically for each country, keeping in mind the cultural, economic and social structures.

4.1. Implications for Policy and Future Research

The findings of this review suggest that there is limited evidence and data on the burden of drowning in Africa. The 2017 Global Burden of Disease (GBD) using statistical models estimated that drowning contributed approximately 0.53% of the total deaths in Africa as a region. Using the GBD to obtain country specific estimates for the countries included in the review showed an average drowning mortality ranging from 1.63 per 100,000 population to 5.73 per 100,000 population [69]. However, existing data on drowning in many countries in Africa are scarce. Therefore, establishing specific databases about injuries like drowning for surveillance and data collection would aid in development of policies and prevention strategies across the different countries. Evidence from research conducted in high income countries like Australia, Canada and New Zealand suggest that robust high-quality data and better data collection system would enable the creation of targeted and effective drowning prevention interventions [70]. Developing the databases will enable cross-country comparison which allows for identification of similarities and improvements in data collection. However, establishing the databases may be challenging for some African countries, especially if drowning is not among the national health priorities. In addition, there was little exploration of the risk factors associated with drowning, highlighting a gap in the literature. Good epidemiological studies are needed to identify the risk factors and evaluate the proposed prevention strategies for drowning in Africa. Furthermore, future research should focus on the intent for drowning in Africa, which would help to inform policies and prevention interventions. A recent article on intentional drowning reported an increasing rate of intentional drowning and proposed a multidisciplinary collaboration public health and other services including mental health, education and drowning prevention organisations to prevent intentional drowning [71].

4.2. Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that describes the epidemiology, risk factors and prevention strategies of drowning in Africa. However, comparing mortality data across the countries within Africa needs to be undertaken with caution given the different measures used to analyse the burden of drowning. Some studies were population-based studies, while other studies reported drowning as a part of a wider study (such as external causes of deaths or all causes of death). An example of the latter is the study by Seleye-Fubara et al. which reported that unintentional drowning accounted for approximately 80% of all drowning deaths [50]. In addition, the completeness and reliability of the data in each country varied with some studies using the national mortality surveillance statistics, while other studies relied on hospital-based data, mortuary-based data and demographic surveillance data. The variability in the sources of data may account for the variable rates of drowning reported in the review.

Other limitations include reviewing only articles published in peer-reviewed journals. We may have missed other high-quality studies that are published in non-peer reviewed journals. In addition, we excluded non-English articles, there is a possibility that we may have missed articles from Africa published in other languages. Furthermore, the majority of studies were from South Africa, it is conspicuous that there is a paucity of data from many countries in Africa. It is uncertain whether such strategies, if implemented, can be generalizable to other African countries besides South Africa.

5. Conclusions

There is a need to address the high rate of drowning in Africa. It is imperative that governments across the nations of Africa establish good injury surveillance systems to accurately understand the burden of drowning to inform approaches for drowning prevention. Good epidemiological studies across all African countries are needed to describe the patterns of drowning and understand risk factors. Further research is needed to investigate the risk factors and to evaluate prevention strategies.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/1010-660X/55/10/637/s1. Table S1: Medline search strategy; Table S2: Quality assessment of included studies using the quality assessment tool for studies with diverse designs (QATSDD); Figure S1: Schematic of study inclusion.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the study concept, design, data extraction, quality assessment and writing of the paper. All authors read and approved the manuscript for submission.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- 1.van Beeck E.F., Branche C., Szpilman D., Modell J.H., Bierens J.J. A new definition of drowning: Towards documentation and prevention of a global public health problem. Bull. WHO. 2005;83:853–856. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) Drowning: 2019. [(accessed on 17 June 2019)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/drowning/en/

- 3.World Health Organization (WHO) Drowning: 2018. [(accessed on 17 June 2019)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/drowning.

- 4.World Health Organization . Global Report on Drowning: Preventing a Leading Killer. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haagsma J.A., Graetz N., Bolliger I., Naghavi M., Higashi H., Mullany E.C., Abera S.F., Abraham J.P., Adofo K., Alsharif U., et al. The global burden of injury: Incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Inj. Prev. 2016;22:3–18. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization (WHO) The African Regional Health Report: The Health of the People. World Health Organization (WHO); Geneva, Switzerland: 2014. p. 214. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agbo N. D’Banj Loses Son. [(accessed on 15 May 2019)];The Guardian. 2018 Available online: https://guardian.ng/life/dbanj-loses-son/

- 8.Tyler M.D., Richards D.B., Reske-Nielsen C., Saghafi O., Morse E.A., Carey R., Jacquet G.A. The epidemiology of drowning in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:413. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4239-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Borse N., Sleet D.A. CDC Childhood Injury Report: Patterns of Unintentional Injuries Among 0- to 19-Year Olds in the United States, 2000–2006. Fam. Community Health. 2009;32:189. doi: 10.1097/01.FCH.0000347986.44810.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Modell J.H. Prevention of needless deaths from drowning. South. Med. J. 2010;103:650–653. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181e10564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moran K., Quan L., Franklin R., Bennett E. Where the evidence and expert opinion meet: A review of open-water recreational safety messages. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2011;5:5. doi: 10.25035/ijare.05.03.05. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quan L., Bennett E.E., Branche C.M. Interventions to prevent drowning. In: Doll L., Bonzo S., Sleet D., Mercy J., Haas E.N., editors. Handbook of Injury and Violence Prevention. Springer; Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: 2008. pp. 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szpilman D., Bierens J.J., Handley A.J., Orlowski J.P. Drowning. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:2102–2110. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1013317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ramos W., Beale A., Chambers P., Dalke S., Fielding R., Kublick L., Langendorfer S.J., Lees T., Quan L., Wernicki P. Primary and secondary drowning interventions: The American Red Cross circle of drowning prevention and chain of drowning survival. Int. J. Aquat. Res. Educ. 2015;9:8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bugeja L., Franklin R.C. An analysis of stratagems to reduce drowning deaths of young children in private swimming pools and spas in Victoria, Australia. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2013;20:282–294. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2012.717086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saunders C., Sewduth D., Naidoo N. Keeping our heads above water: A systematic review of fatal drowning in South Africa. S. Afr. Med. J. 2018;108:61–68. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2017.v108i1.11090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sarrassat S., Mrema S., Tani K., Mecrow T., Ryan D., Cousens S. Estimating drowning mortality in Tanzania: A systematic review and meta-analysis of existing data sources. Inj. Prev. 2018 doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2018-042939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009;151:264–269. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sirriyeh R., Lawton R., Gardner P., Armitage G. Reviewing studies with diverse designs: The development and evaluation of a new tool. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2012;18:746–752. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Streatfield P.K., Khan W.A., Bhuiya A., Hanifi S.M., Alam N., Diboulo E., Niamba L., Sié A., Lankoandé B., Millogo R., et al. Mortality from external causes in Africa and Asia: Evidence from INDEPTH Health and Demographic Surveillance System Sites. Glob. Health Action. 2014;7:25366. doi: 10.3402/gha.v7.25366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Y., Huang Y., Schwebel D.C., Hu G.Q. Unintentional Child and Adolescent Drowning Mortality from 2000 to 2013 in 21 Countries: Analysis of the WHO Mortality Database. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14:875. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14080875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ching-Yih L., Yi-Fong W., Tsung-Hsueh L., Ichiro K. Unintentional drowning mortality, by age and body of water: An analysis of 60 countries. Inj. Prev. 2015;21:e43–e50. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2013-041110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Davis S., Smith L.S. Alcohol and drowning in Cape Town. A preliminary report. S. Afr. Med. J. 1982;62:931–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis S., Smith L.S. The epidemiology of drowning in Cape Town--1980-1983. S. Afr. Med. J. 1985;68:739–742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Donson H., Van Niekerk A. Unintentional drowning in urban South Africa: A retrospective investigation, 2001–2005. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2013;20:218–226. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2012.686041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris N.K., Du Toit-Prinsloo L., Saayman G. Drowning in Pretoria, South Africa: A 10-year review. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2016;37:66–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2015.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meel B.L., Meel B.L. Drowning deaths in Mthatha area of South Africa. Med. Sci. Law. 2008;48:329–332. doi: 10.1258/rsmmsl.48.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knobel G.J., De Villiers J.C., Parry C.D.H., Botha J.L. The causes of non-natural deaths in children over a 15-year period in greater Cape Town. S. Afr. Med. J. 1984;66:795–801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mendes J.F., Mathee A., Naicker N., Becker P., Naidoo S. The prevalence of intentional and unintentional injuries in selected Johannesburg housing settlements. S. Afr. Med. J. 2011;101:835–838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joanknecht L., Argent A.C., van Dijk M., van As A.B. Childhood drowning in South Africa: Local data should inform prevention strategies. Pediatr. Surg. Int. 2015;31:123–130. doi: 10.1007/s00383-014-3637-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kibel S.M., Joubert G., Bradshaw D. Injury-related mortality in South African children, 1981–1985. S. Afr. Med. J. 1990;78:398–403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lerer L.B., Matzopoulos R.G., Phillips R. Violence and injury mortality in the Cape Town metropole. S. Afr. Med. J. 1997;87:298–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pretorius K., Van Niekerk A. Childhood psychosocial development and fatal injuries in Gauteng, South Africa. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41:35–44. doi: 10.1111/cch.12140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meel B.L. Incidence of unnatural deaths in Transkei sub-region of South Africa (1996–2015) S. Afr. Fam. Pract. 2017;59:138–142. doi: 10.1080/20786190.2017.1292697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burrows S., van Niekerk A., Laflamme L. Fatal injuries among urban children in South Africa: Risk distribution and potential for reduction. Bull. World Health Organ. 2010;88:267–272. doi: 10.2471/BLT.09.068486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matzopoulos R., Prinsloo M., Pillay-van Wyk V., Gwebushe N., Mathews S., Martin L.J., Laubscher R., Abrahams N., Msemburi W., Lombard C., et al. Injury-related mortality in South Africa: A retrospective descriptive study of postmortem investigations. Bull. WHO. 2015;93:303–313. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.145771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathews S., Martin L.J., Coetzee D., Scott C., Naidoo T., Brijmohun Y., Quarrie K. The South African child death review pilot: A multiagency approach to strengthen healthcare and protection for children. S. Afr. Med. J. 2016;106:895–899. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i9.11234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Groenewald P., Bradshaw D., Neethling I., Martin L.J., Dempers J., Morden E., Zinyakatira N., Coetzee D. Linking mortuary data improves vital statistics on cause of death of children under five years in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2016;21:114–121. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reid A.E., Hendricks M.K., Groenewald P., Bradshaw D. Where do children die and what are the causes? Under-5 deaths in the Metro West geographical service area of the Western Cape, South Africa, 2011. S. Afr. Med. J. 2016;106:359–364. doi: 10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i4.10521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garrib A., Herbst A.J., Hosegood V., Newell M.L. Injury mortality in rural South Africa 2000 - 2007: Rates and associated factors. Trop. Med. Int. Health. 2011;16:439–446. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2011.02730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Erasmus E., Robertson C., van Hoving D.J. The epidemiology of operations performed by the National Sea Rescue Institute of South Africa over a 5-year period. Int. Marit. Health. 2018;69:1–7. doi: 10.5603/IMH.2018.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Flisher A.J., Joubert G., Yach D. Mortality from external causes in South African adolescents, 1984–1986. S. Afr. Med. J. 1992;81:77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saunders C.J., Adriaanse R., Simons A., van Niekerk A. Fatal drowning in the Western Cape, South Africa: A 7-year retrospective, epidemiological study. Inj. Prev. 2018 doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2018-042945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gelaye K.A., Tessema F., Tariku B., Abera S.F., Gebru A.A., Assefa N., Zelalem D., Dedefo M., Kondal M., Kote M., et al. Injury-related gaining momentum as external causes of deaths in Ethiopian health and demographic surveillance sites: Evidence from verbal autopsy study. Glob. Health Action. 2018;11 doi: 10.1080/16549716.2018.1430669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weldearegawi B., Ashebir Y., Gebeye E., Gebregziabiher T., Yohannes M., Mussa S., Berhe H., Abebe Z. Emerging chronic non-communicable diseases in rural communities of Northern Ethiopia: Evidence using population-based verbal autopsy method in Kilite Awlaelo surveillance site. Health Policy Plan. 2013;28:891–898. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czs135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ohene S.A., Tettey Y., Kumoji R. Injury-related mortality among adolescents: Findings from a teaching hospital’s post mortem data. BMC Res. Notes. 2010;3:124. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-3-124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ossei P.P.S., Ayibor W.G., Agagli B.M., Aninkora O.K., Fuseini G., Oduro-Manu G., Ka-Chungu S. Profile of unnatural mortalities in Northern part of Ghana; a forensic-based autopsy study. J. Forensic Leg. Med. 2019;65:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chasimpha S., McLean E., Chihana M., Kachiwanda L., Koole O., Tafatatha T., Mvula H., Nyirenda M., Crampin A.C., Glynn J.R. Patterns and risk factors for deaths from external causes in rural Malawi over 10 years: A prospective population-based study Health behavior, health promotion and society. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1036. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-2323-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Purcell L., Mabedi C.E., Gallaher J., Mjuweni S., McLean S., Cairns B., Charles A. Variations in injury characteristics among paediatric patients following trauma: A retrospective descriptive analysis comparing pre-hospital and in-hospital deaths at Kamuzu Central Hospital, Lilongwe, Malawi. Malawi Med. J. 2017;29:146–150. doi: 10.4314/mmj.v29i2.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seleye-Fubara D., Nicholas E.E., Esse I. Drowning in the Niger Delta region of Nigeria: An autopsy study of 85 cases. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 2012;19:111–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Osime O.C., Ighedosa S.U., Oludiran O.O., Iribhogbe P.E., Ehikhamenor E., Elusoji S.O. Patterns of trauma deaths in an accident and emergency unit. Prehospital Disaster Med. 2007;22:75–78. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X00004374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Olatunya O.S., Isinkaye A.O., Oluwadiya K.S. Profile of non-accidental childhood injury at a tertiary hospital in south-west Nigeria. J. Trop. Pediatr. 2015;61:174–181. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fmv009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lett R.R., Kobusingye O.C., Ekwaru P. Burden of injury during the complex political emergency in northern Uganda. Can. J. Surg. 2006;49:51–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kobusingye O., Tumwesigye N.M., Magoola J., Atuyambe L., Olange O. Drowning among the lakeside fishing communities in Uganda: Results of a community survey. Int. J. Inj. Control Saf. Promot. 2017;24:363–370. doi: 10.1080/17457300.2016.1200629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kobusingye O., Guwatudde D., Lett R. Injury patterns in rural and urban Uganda. Inj. Prev. 2001;7:46–50. doi: 10.1136/ip.7.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Koné S., Fürst T., Jaeger F.N., Esso E.L.J.C., Baïkoro N., Kouadio K.A., Adiossan L.G., Zouzou F., Boti L.I., Tanner M., et al. Causes of death in the Taabo health and demographic surveillance system, Cǒte d'Ivoire, from 2009 to 2011. Glob. Health Action. 2015;8:27271. doi: 10.3402/gha.v8.27271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Odhiambo F.O., Beynon C.M., Ogwang S., Hamel M.J., Howland O., van Eijk A.M., Norton R., Amek N., Slutsker L., Laserson K.F., et al. Trauma-related mortality among adults in rural western Kenya: Characterizing deaths using data from a health and demographic surveillance system. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e79840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0079840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mamady K., Yao H., Zhang X., Xiang H., Tan H., Hu G. The injury mortality burden in Guinea. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:733. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moshiro C., Mswia R., Alberti K.G.M.M., Whiting D.R., Unwin N., Setel P.W. The importance of injury as a cause of death in sub-Saharan Africa: Results of a community-based study in Tanzania. Public Health. 2001;115:96–102. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(01)00426-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Grainger C.R. Drowning accidents in the Seychelles. J. R. Soc. Health. 1985;105:129–130. doi: 10.1177/146642408510500408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chitiyo M.E. Causes of unnatural adult deaths in the Bulawayo area. Cent. Afr. J. Med. 1974;20:57–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.World Health Organization ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. [(accessed on 28 July 2019)]; Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http%3a%2f%2fid.who.int%2ficd%2fentity%2f128104623.

- 63.Wikimedia Commons Blank Map of Africa. [(accessed on 20 May 2019)];File: Blank Map-Africa.svg. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Blank_Map-Africa.svg.

- 64.Manuele F.A. Risk assessment and hierarchies of control. Prof. Saf. 2005;50:33–39. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cinnamon J., Schuurman N. Injury surveillance in low-resource settings using Geospatial and Social Web technologies. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2010;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-9-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lukaszyk C., Ivers R.Q., Jagnoor J. Systematic review of drowning in India: Assessment of burden and risk. Inj. Prev. 2018;24:451. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev-2017-042622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.World Health Organization Global Health Estimates (GHE) 2016. [(accessed on 13 June 2019)]; Available online: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/

- 68.Driscoll T.R., Harrison J.A., Steenkamp M. Review of the role of alcohol in drowning associated with recreational aquatic activity. Inj. Prev. 2004;10:107. doi: 10.1136/ip.2003.004390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) GBD Compare Data Visualization. [(accessed on 28 July 2019)];2017 Available online: https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-compare/

- 70.Peden A.E., Franklin R.C., Clemens T. Exploring the burden of fatal drowning and data characteristics in three high income countries: Australia, Canada and New Zealand. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:794. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7152-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cenderadewi M., Franklin R.C., Peden A.E., Devine S. Pattern of intentional drowning mortality: A total population retrospective cohort study in Australia, 2006–2014. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:207. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-6476-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.