Abstract

Aim:

The aim of this study wass to compare the cytological features of pleural exudative fluids by conventional smear (CS) method and cell block (CB) method and also to assess the utility of the combined approach for cytodiagnosis of these effusions.

Materials and Methods:

In all, 113 pleural exudative fluid samples were subjected to evaluation by both CS and CB methods over a period of 2 years. Cellularity, architecture patterns, morphological features, and yield for malignancy were compared, using the two methods. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and accuracy for diagnosis of malignancy were calculated for both the methods, using histology as a gold standard.

Results:

CB method provided higher cellularity, better architectural patterns, and additional yield for malignancy when compared with CS method. For 22 (40%) patients, histologic subtype was determined with CB especially for adenocarcinoma. The sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values of cytology and CB were 48%, 100%, 100%, 67.8% and 59.2%, 100%, 100%, 72.8%, respectively.

Conclusion:

CB technique definitively increased detection of malignancy in pleural fluid effusion when used as an adjunct to CSs. Also, CB provides material suitable for molecular genetic analysis for targeted therapies especially in the treatment of adenocarcinoma.

Keywords: Cell block, cytology, pleural efusion

INTRODUCTION

Cytologic examination of pleural fluid is the easiest and least invasive way to diagnose malignant effusions, although it has limited sensitivity. Scientific guidelines indicate that preparing cell blocks (CBs) from pleural effusion samples, in addition to smears, allow for “microhistology” of the cellular solid portion which may lead to greater diagnostic accuracy.[1] Its main advantage is the preservation of tissue architecture and obtaining multiple sections for special stains and immunohistochemistry.[2,3] However, it is not used widely in routine daily clinical practice. Nevertheless, it is a simple method requiring no special training or instrument. It is safe, cost-effective, and reproducible even in resource-limited rural areas.[4] In this small study, we aimed to compare the cytological features of pleural exudative fluids by conventional smear (CS) method and CB method and also to assess the utility of a combined approach for cytodiagnosis of the effusions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

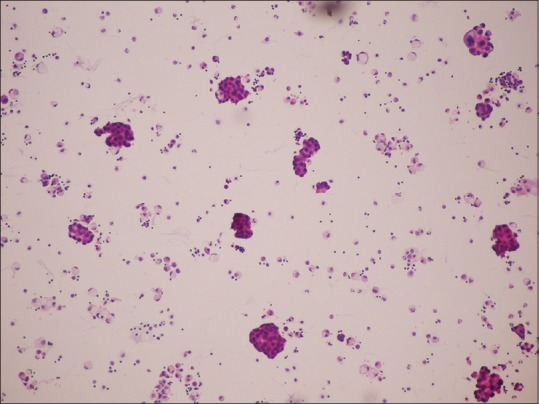

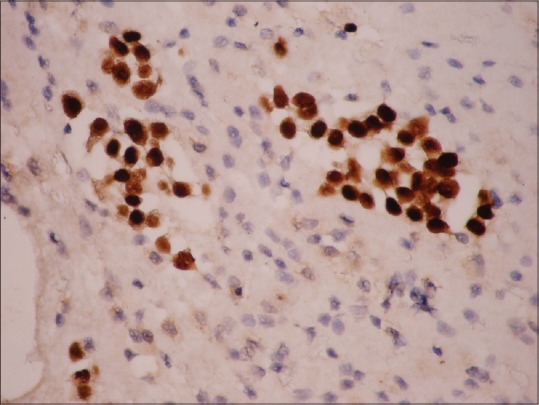

The study included 146 patients clinically and radiologically proven to have pleural effusion between March 2017 and January 2018. The study was approved by our institutional local ethical committee. The fluids gathered from the patients were divided into two equal parts – while in one half conventional cytological analysis was done, in the other half the analysis was done using CB technique. Half of the specimens were centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 rpm. The sediment acquired was applied on the slide and stained with routine Giemsa and hematoxylin–eosin stains [Figure 1]. The other half of the specimens were centrifuged for 5 min at 2000 rpm. The residual fluid over the tube was emptied. The sediment in the bottom was gathered on the blotting paper by turning the tube upside down. The material obtained was fixed with 10% formalin solution, and then routine histological follow-up was done. After follow-up, paraffin blocks were formed and paraffin blocks were cut into 4-μm sections. These sections were stained with routine hematoxylin–eosin. After light microscope examination, in required cases, special histochemical and immunohistochemical studies such as thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) and calretinin were done [Figure 2].

Figure 1.

Smear with hematoxylin–eosin stain ×100

Figure 2.

Tumor cells positive for TTF-1 on cell block ×100

In cytological diagnosis, the conventional diagnosis criteria were divided into three categories as benign, malignant, and undetermined. In CB examination, histopathological diagnosis was done in cases with sufficient cell counts. Patients who cannot be diagnosed with cytology and/or CB underwent pleural biopsy or video-associated thoracoscopic surgery.

Statistical analysis

SPSS for Windows 20.0 was used for statistical analyses. The descriptive statistics were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for continuous variables and as frequency (%) for categorical variables. Interrater agreement was computed and a Kappa value was given. McNemar's test method was used in the investigation of difference between CB and CS cytology. Cytology and CB results were compared with the final diagnosis separately. Sensitivity and specificity were calculated. P value < 0.05 was assumed to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

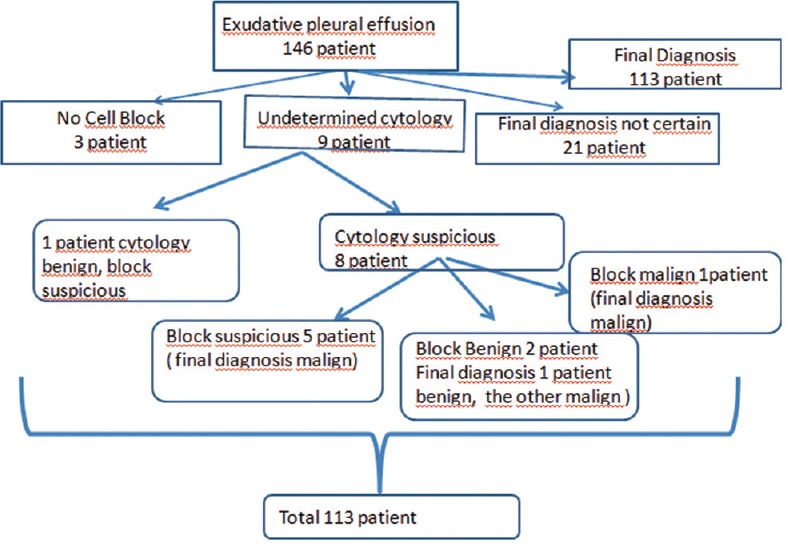

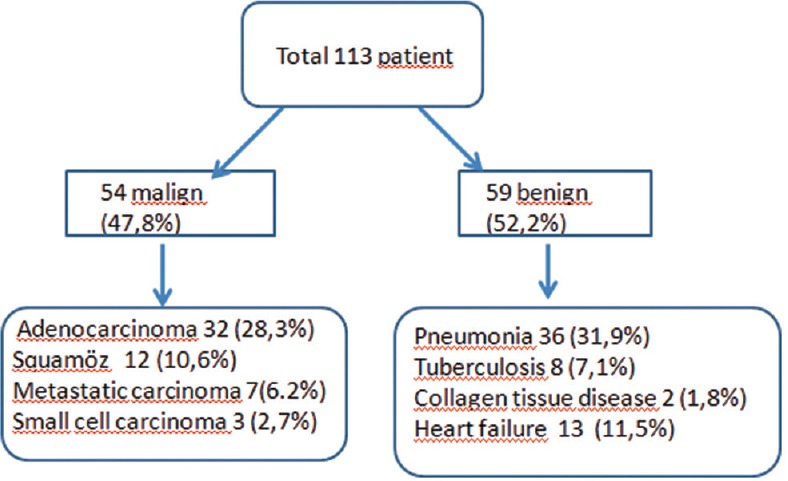

A total of 146 patients with exudative pleural effusion underwent thoracentesis, in the study period, as shown in Figure 3. Fifty-four patients diagnosed as malignant and 59 patients diagnosed as benign were included in the study [Figure 4]. The demographic characteristics of 113 patients are shown in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Flow chart of patients who underwent thoracentesis

Figure 4.

The diagnosis of the total 113 patients

Table 1.

Demographic data of 113 patients

| Variables | n (%) or mean±SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean±SD | 60.3±14.5 |

| Gender, female/male | 78/35 (69% M) |

| Known malignancy | |

| Lung | 46 (31.9%) |

| Breast | 30 (21.2%) |

| Ovary | 5 (3.4%) |

| Colon | 2 (1.4%) |

| Stomach | 2 (1.4%) |

| Others | 4 (4.1%) |

| Final diagnosis | |

| Pneumonia | 36 (31.9%) |

| Carcinoma | 54 (47.8%) |

| Tuberculosis | 8 (7.1%) |

| Collagen tissue disorders | 2 (1.8%) |

| Heart failure | 13 (11.5%) |

| Cytology | |

| Benign | 87 (77%) |

| Malignant | 26 (23) |

| Cell block | |

| Benign | 81 (71.7%) |

| Malignant | 32 (28.3%) |

| Subtype of cancer by cell block | |

| Yes | 22 (40%) |

| No | 32 (60%) |

SD: Standard deviation

For 22 (40%) patients, histological subtype was determined with CB especially for adenocarcinoma [Table 2]. The agreement of cytology and CB in determining the final diagnosis was only fair (r = 0492 and r = 0.603, respectively; P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of 22 patients’ subtyping by cell block

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | 14 male/8 female |

| Known malignancy | 14 (63.6%) |

| Final diagnosis | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 1 |

| Adenocarcinoma | 18 |

| Small cell carcinoma | 1 |

| Metastatic carcinoma | 2 |

| Cytology | |

| Benign | 6 |

| Malignant | 16 |

The sensitivity, specificity, positive, and negative predictive values of cytology and CB were 48%, 100%, 100%, 67.8% and 59.2%, 100%, 100%, 72.8%, respectively [Table 3]. The CB was significantly better than cytology (P = 0.031) as a diagnostic tool.

Table 3.

Diagnostic efficiency of cell block and cytology

| Cytology | Cell block | Cytology and cell block | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, % | 48 | 59.2 | 59.2 |

| Specificity, % | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Positive predictive value, % | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Negative predictive value, % | 67.8 | 72.8 | 72.8 |

| Accuracy, % | 75.2 | 80.5 | 80.5 |

DISCUSSION

In patients with symptoms suspicious of lung cancer and pleural effusion, the first process is to do thoracentesis. The examination of the pleural fluid cytology is crucial for the pleural involvement of the lung cancer or the visceral or parietal pleural metastatic involvement of an extrapulmonary malignancy.[5] During thoracentesis, closed-blind pleural biopsy can be performed simultaneously to obtain pleural tissue for histology. However, its diagnostic yield is less sensitive than CS, as pleural metastases tend to be focal in the parietal pleura.[6] In addition, pleural biopsy sometimes fails to provide adequate tissue. Furthermore, complications such as pneumothorax, hemothorax, extravasation of Pleural fluid (PF), and injury to adjacent organs may occur.

CB technique is one of the oldest methods used for the evaluation of body fluids. Using 10% alcohol-formalin as a fixative increases the cellularity due to less destruction by the fixative, providing better morphological details and improving the sensitivity of the diagnosis. Multiple sections can be obtained by the CB method for special stains and immunohistochemical studies.[7]

In our study, most of the pleural effusions were due to lung cancer, because our study is performed in the center of a chest diseases referral hospital. The second most common malignancy causing pleural effusion was breast cancer. Khan et al. showed carcinoma of the lung was the most common site of malignant effusion followed by carcinoma of ovary and gastrointestinal tract.[8]

In our study, adding the CB method to CS provided a diagnosis of malignancy in six more patients. Also, CB provided the subtyping of lung cancer as adenocarcinoma in 22 patients. Köksal et al. detected that it was possible to type the cancer with CB in the cases considered malignant with CS cytology technique.[9] In another study, out of 12 cases considered benign with CS cytology technique, it was found out that they were actually malignant with CB technique. Also, adenocarcinoma was the most common diagnosis with CB technique as in our study.[10] The recovery rate of tumor cells by CB method in a study by Khan et al. was 20% greater than that obtained for specimen examined in CSs.[8] Bodele et al. diagnosed additional 7% malignancies in CB methods when compared with conventional smear methods.[11] Thapar et al. showed a diagnostic yield of 20% by CB preparations.[12] Moreever, subtyping the lung cancer histologically is important in choosing the right chemotherapeutic agents especially targeted therapies for adenocarcinoma.

CB sensitivity (59.2%) was more than CS sensitivity (48%) in our study. But CB and cytology smear and CB combination were found to have the same sensitivity (59.2%). In a recent study,[13] CS and CB provided a similar diagnostic yield (48.7% vs. 49.9%), while the combination of both gave a higher yield (57.2%). Combination of CS and CB improved the diagnostic yield to 71.2%.

This study has limitations. First, pathologists were not blinded to clinical data and the interpretation of CBs may also have been influenced by the results of cytology smears, which however, is a reflection of daily practice. We sent only 10 mL of pleural fluid for preperation of smears, and that the incidence of positive results depends on the volume of pleural fluid submitted (the larger the amount, the greater the diagnostic accuracy) and other factors such as the way in which the specimens are examined (e.g. CBs along with smears, as this study supports), the tumor type, and the experience of the cytopathologist.

In conclusion, CB technique definitively increases detection of malignancy in pleural fluid effusion when used as an adjunct to CSs. Also, CB provides material suitable for molecular genetic analysis for targeted therapies especially in treatment of adenocarcinoma.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hooper C, Lee YC, Maskell N. BTS Pleural Guideline Group. Investigation of a unilateral pleural effusion in adults: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65(Suppl. 2):ii4–17. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.136978. doi: 10.1136/thx. 2010.136978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nathan NA, Narayan E, Smith MM, Horn MJ. Cytology improved preparation and its efficacy in diagnostic cytology. Am J Clin Pathol. 2000;114:599–606. doi: 10.1309/G035-P2MM-D1TM-T5QE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jing X, Li QK, Bedrossian U, Michael CW. Morphologic and immunocytochemical performance of effusion cell blocks prepared using 3 different methods. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;139:177–82. doi: 10.1309/AJCP83ADULCXMAIX. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim JH, Kim GE, Choi YD, Lee JS, Lee JH, Nam JH, et al. Immunocytochemical panel for distinguishing between adenocarcinomas and reactive mesothelial cells in effusion cell blocks. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:258–61. doi: 10.1002/dc.20986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Porcel JM, Quirós M, Gatius S, Bielsa S. Examination of cytological smears and cell blocks of pleural fluid: Complementary diagnostic value for malignant effusions. Rev Clin Esp. 2017;217:144–8. doi: 10.1016/j.rce.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nance KV, Shermer RW, Askin FB. Diagnostic efficacy of pleural biopsy as compared with that of pleural fluid examination. Mod Pathol. 1991;4:320–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunze H. The comparative diagnostic accuracy, efficiency and specificity of cytologic techniques used in the diagnosis of malignant neoplasm in serious effusions of the pleural and pericardial cavities. Acta Cytol. 1964;8:150–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Khan N, Sherwani RK, Afroz N, Kapoor S. The cytodiagnosis of malignant effusions and determination of the primary site. J Cytol. 2005;22:107–10. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Köksal D, Demıraǧ F, Bayız H, Koyuncu A, Mutluay N, Berktaş B, et al. The cell block method increases the diagnostic yield in exudative pleural effusions accompanying lung cancer. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2013;29:165–70. doi: 10.5146/tjpath.2013.01184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ugurluoglu C, Kurtipek E, Unlu Y, Esme H, Duzgun N. Importance of the cell block technique in diagnosing patients with non-small cellcarcinoma accompanied by pleural effusion. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2015;16:3057–60. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2015.16.7.3057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bodele AK, Parate SN, Wadadekar AA, Bobhate SK, Munshi MM. Diagnostic utility of cell block preparation in reporting of fluid cytology. J Cytol. 2003;20:133–5. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thapar M, Mishra RK, Sharma A, Goyal V, Goyal V. A critical analysis of the cell block versus smear examination in effusions. J Cytol. 2009;26:60. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.55223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Assawasaksakul T, Boonsarngsuk V, Incharoen P. A comparative study of conventional cytology and cell block method in the diagnosis of pleural effusion. J Thorac Dis. 2017;9:3161–7. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.08.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]