Abstract

Background:

Lactic acidosis is a rare but serious complication associated with metformin therapy in certain high-risk patients. NICE guidelines and the British National Formulary advise the discontinuation of metformin before surgery. The drug manufacturer's datasheet advises the withdrawal of metformin 48 h before surgery. However, the data regarding perioperative use of metformin is scarce.

Aims:

To evaluate the effect of continuation of metformin till night before surgery on lactate levels in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

Materials and Methods:

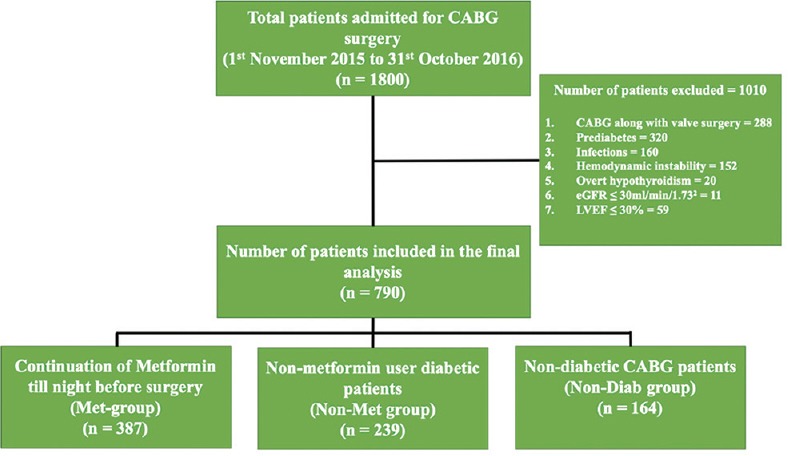

In this prospective cohort study, 1,800 consecutive patients who underwent CABG between 1st November 2015 and 31st October 2016 were enrolled. Following exclusion criteria, a total of 790 subjects were included for final analysis. Three-hundred and eight seven (48.9%) patients with diabetes received metformin till night before surgery (Met group), 239 (30.3%) patients with diabetes were non-metformin users (Non-Met group), and 164 (20.8%) patients were having no diabetes (Non-Diab group). Lactate levels and arterial pH were measured using arterial blood gas machine. Postoperative morbidity outcome data were obtained by collecting clinical data, routine biochemistry, and chest imaging.

Results:

The mean metformin dose was 1,124.6 mg/day (SD: 509.3; range: 500–2,500 mg/day). Mean postoperative lactate levels were 1.91 ± 0.7 in Met group, 2.04 ± 0.79 in Non-Met group, and 2.07 ± 0.78 in Non-Diab group. Lactic acidosis occurred in 41 patients and there was no difference among the groups [Met group = 18 (4.7%); Non-Met group = 14 (5.9%)]. Among secondary outcome measures, acute renal failure occurred more frequently in diabetic patients [Met group = 46 (11.9%) and Non-Met group = 32 (13.4%)] as compared with non-diabetic patients. There were no differences with regard to pneumonia, length of ICU stay, and duration of ventilatory support among the three groups.

Conclusions:

Continuation of metformin till night before surgery is not associated with significant changes in lactate levels in patients undergoing CABG.

Keywords: Coronary artery bypass graft, lactate levels, lactic acidosis, metformin, type 2 diabetes

BACKGROUND

Metformin remains the first choice of treatment for patients with type 2 diabetes in the absence of contraindications.[1] Concerns about the risk of lactic acidosis delayed the introduction of metformin into the clinical practice in the USA until 1995, and such concerns are persistent till date.[2] Although the incidence of lactic acidosis in patients taking metformin is very low, but can be fatal at times.[3] Metformin-associated lactic acidosis (MALA) is more likely in patients with underlying predisposing conditions, such as renal impairment, hepatic disease, congestive heart failure, or severe sepsis.[4] However, more and more studies are vouching for the safety of metformin, even in patients with underlying aforementioned predisposing conditions.[5,6,7] The data regarding continuation of metformin in the perioperative period of a major surgery is debatable. A few studies suggest discontinuation of metformin before a major surgery,[8,9] while other studies found no reason for this suggestion.[10,11] NICE guidelines and the British National Formulary advise the discontinuation of metformin before surgery.[12,13] The drug manufacturer's datasheet advise the withdrawal of metformin 48 h before surgery.[14] A small retrospective study found no increase in incidence of lactic acidosis in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, wherein metformin administration was continued in the perioperative period.[15] Therefore, the current prospective study aimed to evaluate the effect of continuation of metformin till night before surgery on blood lactate levels and immediate postoperative outcome measures in patients undergoing CABG surgery.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The present study is a prospective observational cohort study conducted at a tertiary care hospital, Medanta the Medicity, Gurugram, Haryana, India. The study population comprised 1,800 consecutive patients who underwent elective CABG surgery between 1st November 2015 and 31st October 2016. Exclusion criteria were prediabetes (HbA1C = 5.7--6.4%), evident infections (urinary tract infections, respiratory tract infections, and sepsis), liver dysfunction (SGOT and/or SGPT ≥3 times the upper limit of normal range), renal failure (estimated GFR by MDRD ≤30 ml/min/1.73 m2), severe LV dysfunction (ejection fraction ≤30%), overt hypothyroidism (TSH ≥10 mIU/mL), and hemodynamically unstable patients.

Study approval

The protocol was approved by the institutional ethics review board (MICR-530/2015; Gurugram, Haryana, India) and was approved by the Ethics Committee on 5th October 2015. Need for a separate informed written consent was waived off by the review board, as there was consent for the surgery that clearly stated that the data could be used for the study purpose.

Study participants

Of 790 subjects that met the inclusion, 387 (48.9%) patients with diabetes received metformin (Met group), 239 (30.3%) patients with diabetes were non-metformin users (Non-Met group), and 164 (20.8%) patients had no diabetes (Non-Diab group). As per our institutional practice protocol, patients in Met group were continued on metformin till night before surgery. Eligible patients received maximum of 2 g of metformin per day. Metformin was restarted in suitable patients in postoperative period once these patients were able to tolerate normal diet. During intraoperative and immediate postoperative period, glycemic control was achieved using intravenous insulin infusion and subsequently with subcutaneous basal and bolus insulin regimen (three pre-meal short-acting insulin analogues and one long-acting basal insulin analogue) as per our protocol.[16]

Biochemical measurements

ABG was done in preoperative period (<2 h before surgery), and in immediate postoperative period (0 h, patient reaching to ICU), and again after 12, 24, and 36 h. Blood sample for ABG was taken from arterial line. ABG was done using a standard 3 ml syringe with a 25-gauge needle. The sealed syringe was immediately taken to a blood gas analyzer machine (RADIOMETER ABL 800 BASIC) installed in ICU. Lactate, pH, and bicarbonate levels were recorded. High lactate levels were defined as blood lactate level ≥2.5 mmol/l. Lactic acidosis was defined as blood lactate levels ≥5.0 mmol/l along with pH <7.35.[17] Serum creatinine was measured in preoperative period and postoperative period daily for 7 days. Acute renal failure was defined as rise in serum creatinine of ≥0.3 mg/dl within 48 h in postoperative period according to guidelines by Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO).[18] Pneumonia was diagnosed on the basis of clinical features and radiology with or without microbial cultures. Clinical criteria included at least two of the following: fever greater than 38°C, leukocytosis (>1,200/mm3), or leukopenia (<4,000/mm3), and purulent respiratory secretions. Radiological findings included the presence of a new or progressive pulmonary infiltrate.[19]

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis included profiling of patients on different demographic, clinical, and laboratory parameters. For each of these groups, quantitative data were presented in terms of means and standard deviations. Qualitative/categorical data were presented as absolute numbers and proportions. Cross tables were generated and Chi-square test was used for testing of associations. Student's t-test was used for comparison of quantitative outcome parameters. Comparison of quantitative parameters between multiple groups was done using One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Delta value (postoperative value minus preoperative value) was calculated in each group for different ABG parameters. Delta values were compared between groups using independent samples t-test. P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. SPSS software, version 24.0 was used for analysis.

RESULTS

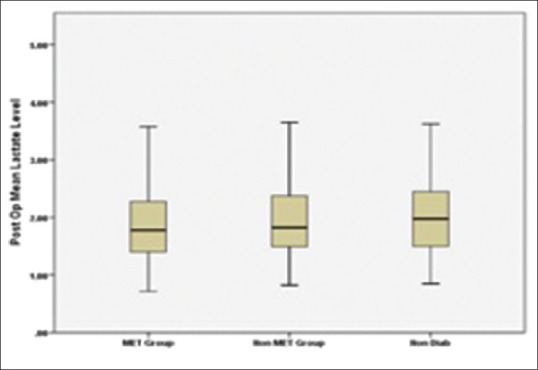

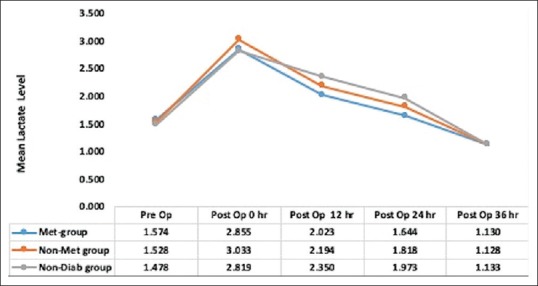

Derivation of the study cohort, number of patients excluded, and number of patients included in the final analysis are shown in Figure 1. Preoperative characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. The mean metformin dose was 15.96 mg/kg/day (SD: 7.596; range: 5.3–43.2 mg/kg/day). Chronic kidney disease (CKD), coronary artery disease involving triple vessel (CAD-TVD), and hypertension were more prevalent in patients with diabetes as compared with those with no diabetes. In all groups, there was increase in serum lactate levels and decrease in pH and bicarbonate levels postoperatively [Table 2]. There was no significant difference in preoperative lactate levels among the three groups. Mean postoperative lactate levels (mmol/l) were 1.91 ± 0.7 in Met group, 2.04 ± 0.79 in Non-Met group, and 2.07 ± 0.78 in Non-Diab group [Figure 2]. Mean postoperative lactate levels were significantly low in metformin users compared with other groups (Met group versus Non-Met group, P = 0.035; Met group versus Non-Diab group, P = 0.020; and Non-Met group versus Non-Diab, P = 0.709). The percentage of subjects with normal postoperative lactate levels (mmol/l) were 60.7% in Met group, 55.6% in Non-Met group, and 51.8% in Non-Diab group. The differences in normal postoperative lactate levels (mmol/l) were not statistically significant among three groups [Table 3]. Similarly, rise in blood lactate levels (Δ lactate) were significantly smaller in metformin groups compared with other groups. Peak levels of lactate were attained at immediate postoperative period (0 h) and decreased toward baseline at 24 h [Figure 3]. Lactic acidosis in postoperative period occurred in 18 (4.7%) patients in the Met group, 14 (5.9%) in Non-Met group, and 9 (5.5%) in Non-Diab group. Factors causing lactic acidosis were evaluated using logistic regression analysis [Table 4]. Use of On-Pump CABG surgery was an independent predictor of lactic acidosis. There was no correlation between dose of metformin and preoperative pH (r = 0.02, P = 0.690); lactate (r = 0.073, P = 0.152); and bicarbonate levels (r = −0.059, P = 0.252). There was also no correlation between dose of metformin and mean postoperative pH (r = −0.014, P = 0.792), lactate (r = −0.018, P = 0.731), and bicarbonate levels (r = −0.026, P = 0.615).

Figure 1.

Consort diagram. Disposition of study participants is shown. A total of 1,800 patients admitted for elective CABG surgery were enrolled. Following exclusion of 1,010 participants, 790 were finally analyzed. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft

Table 1.

Preoperative characteristics of all patients

| Parameters | Met-group (n=387) | Non-Met group (n=239) | Non-Diab group (n=164) | P (Met-group vs. Non-Met group) | P (Met-group vs. Non-Diab group) | P (Non-Met group vs. Non-Diab group) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60.3±8.4 | 61.4±8.5 | 59.6±10.1 | 0.106 | 0.418 | 0.055 |

| Male n (%) | 338 (87.3) | 207 (86.6) | 148 (90.2) | 0.792 | 0.387 | 0.348 |

| BMI | 26.4±4.2 | 26.1±3.7 | 25.8±4.0 | 0.337 | 0.112 | 0.438 |

| CKD | 25 (6.5) | 24 (10) | 3 (1.8) | 0.125 | 0.015 | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 285 (73.6) | 179 (74.9) | 92 (56.1) | 0.778 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 |

| PVD | 17 (4.4) | 12 (5) | 3 (1.8) | 0.701 | 0.212 | 0.114 |

| CAD-TVD | 351 (90.7) | 216 (90.4) | 133 (81.1) | 0.251 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| LVEF (%) | 49.91±8.1 | 47.6±8.9 | 49.9±8.2 | 0.001 | 0.939 | 0.011 |

Data is presented as mean±SD and percentage. BMI: Body mass index; CKD: Chronic kidney disease; PVD: Peripheral vascular disease; CAD-TVD: Coronary artery disease-triple vessel disease; LVEF: Left ventricular ejection fraction

Table 2.

Preoperative and postoperative ABG parameters

| Parameters | Met-group (n=387) | Non-Met group (n=239) | Non-Diab group (n=164) | P Met-group vs. Non-Met group | P Met-group vs. Non-Diab group | P Non-Non-Met group vs Non-Diab group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative lactate levels | 1.57±0.62 | 1.53±0.6 | 1.48±0.56 | 0.370 | 0.090 | 0.395 |

| Mean postoperative lactate | 1.91±0.7 | 2.04±0.79 | 2.07±0.78 | 0.035 | 0.020 | 0.709 |

| ∆ lactate | 0.34±0.87 | 0.52±0.82 | 0.59±0.87 | 0.011 | 0.003 | 0.443 |

| Preoperative pH | 7.43±0.03 | 7.44±0.03 | 7.44±0.04 | <0.0001 | 0.066 | 0.366 |

| Mean postoperative pH | 7.40±0.03 | 7.40±0.03 | 7.40±0.03 | 0.195 | 0.124 | 0.734 |

| ∆ pH | −0.03±0.04 | −0.04±0.04 | −0.03±0.04 | 0.046 | 0.672 | 0.253 |

| Preoperative HCO3 levels | 25.42±2.51 | 25.78±2.46 | 25.71±2.76 | 0.079 | 0.229 | 0.791 |

| Mean postoperative HCO3 levels | 22.88±1.84 | 23.13±1.71 | 23.69±1.54 | 0.093 | <0.0001 | 0.001 |

| ∆ HCO3 | −2.54±2.99 | −2.63±2.67 | -2.02±3.13 | 0.680 | 0.070 | 0.037 |

| Lactate acidosis n (%) (lactate >5.0, PH <7.35) | 18 (4.7%) | 14 (5.9%) | 9 (5.5%) | 0.082 | 0.208 | 0.579 |

Data is presented as mean±SD. ∆ = delta (postoperative - preoperative)

Figure 2.

Postoperative mean serum lactate levels in the three groups

Table 3.

Further analysis of postoperative lactate levels

| Groups | Postoperative lactate levels |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean lactate levels (mmol/L) ± SD | CV | Number of subjects with normal lactate levels (n) | Proportion of subjects with normal lactate levels (%) | |

| Met group (n=387) | 1.91±0.70 | 36.6% | 235 | 60.7 |

| Non-Met group (n=239) | 2.04±0.79 | 38.7% | 133 | 55.6 |

| Non-Diab group (n=164) | 2.07±0.78 | 37.7% | 85 | 51.8 |

SD: Standard deviation; CV: Coefficient of variation; defined as (SD/Mean) ×100; normal lactate levels were defined as lactate levels <2 mm/l of blood

Figure 3.

Changes in lactate levels (mmol/L) in the three groups. Met group, patients receiving metformin till night before surgery; Non-Met group, patients who have diabetes but not receiving metformin; Non-Diab group, patients who have no diabetes and underwent CABG surgery

Table 4.

Logistic regression for lactic acidosis

| Parameters | Univariate OR (CI) | Multivariate OR (CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Age more than 70 years | 1.18 (0.51-2.74) | 0.92 (0.38-2.21) |

| Postoperative renal failure | 2.47 (1.13-5.37) | 2.23 (0.97-5.09) |

| LVEF <40 | 1.94 (0.99-3.78) | 1.76 (0.87-3.56) |

| On-pump CABG | 3.17 (1.53-6.59) | 3.29 (1.35-8.00) |

| Intra-aortic Balloon Pump | 1.67 (0.57-4.91) | 1.54 (0.49-4.81) |

| Metformin use | 1.29 (0.63-2.66) | 1.07 (0.51-2.25) |

| Use of inotropes | 1.68 (0.38-7.41) | 2.24 (0.49-10.32) |

| Use of blood and blood product | 1.57 (0.83-2.95) | 1.01 (0.47-2.18) |

On-pump CABG was associated with lactic acidosis

Intraoperatively use of blood products was more common in patients with diabetes. Length of hospital stay and duration of inotropes were more common in Non-Met group patients compared with Met-group and Non-Diab group. Postoperatively renal failure was more common in patients with diabetes [Table 5].

Table 5.

Morbidity (intraoperative and postoperative) characteristics

| Parameters | Met-group (n=387) | Non-Met group (n=239) | Non-Diab group (n=164) | P Met-group vs. Non-Met group | P Met-group vs. Non-Diab group | P Non-Met vs. Non-Diab group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Use of IABP | 21 (5.4) | 22 (9.2) | 7 (4.3) | 0.080 | 0.080 | 0.080 |

| Off-pump CABG | 350 (90.4%) | 205 (85.8%) | 146 (89.0%) | 0.091 | 0.642 | 0.368 |

| Use of inotropes | 377 (97.4%) | 232 (97.1%) | 156 (95.1%) | 0.804 | 0.361 | 0.191 |

| Use of blood and blood products | 157 (40.6) | 114 (47.7) | 49 (29.9) | 0.082 | 0.018 | 0.000 |

| Renal failure | 46 (11.9%) | 32 (13.4%) | 8 (4.9%) | 0.619 | 0.012 | 0.006 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (0.3%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0.432 | 1.000 | 0.241 |

| Requirement of dialysis | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.8) | 0 (0.0) | 0.071 | - | - |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | 2.9±1.4 | 3.1±1.3 | 3.2±2.2 | 0.214 | 0.939 | 0.527 |

| Duration of ventilatory support (h) | 21.6±9.2 | 22.6±10 | 21.4±5.9 | 0.198 | 0.823 | 0.174 |

| Duration of inotropes (hours) | 21.33±24.77 | 26.84±27.14 | 21.62±22.41 | 0.009 | 0.897 | 0.043 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 9.5±2.7 | 10.1±3.8 | 9.6±2.9 | 0.017 | 0.648 | 0.149 |

Data is presented as mean±SD and percentage. IABP: Intra-aortic balloon pump; CABG: Coronary artery bypass graft

DISCUSSION

The current large study demonstrated that continuation of metformin till night before CABG surgery in patients with type 2 diabetes was not associated with increase in blood lactate levels or lactic acidosis. There were also no different immediate postoperative outcome measures when compared with non-metformin users undergoing CABG surgery or with patients without diabetes undergoing CABG. Our study revealed that there was rise in serum lactate levels in all the three groups postoperatively but was more common in patients without diabetes and non-metformin users. Lactic acidosis occurred more frequently in non-metformin users but was not statistically significant. In a small case control study, Nazer et al. also showed that the mean peak serum lactate level was significantly higher in the non-metformins (5.4 ± 2.6 vs. 7.4 ± 4.1 mmol/l; P = 0.001) where metformin was administered till the day of surgery and was resumed immediately following extubation.[15] In an RCT, 200 patients with type 2 diabetes were studied following CABG surgery. One hundred patients received insulin only and another 100 patients received insulin plus metformin combination. All the oral antihyperglycemic agents were stopped 2 days before surgery and glucose was managed with insulin. Metformin was started 3 h after extubation in the metformin group. Lactic acidosis was not observed in either of the study arms. Blood lactate levels in both groups gradually decreased during the study, but there was no significant difference between the two groups.[20] In a systematic review by Salpeter et al., pooled data from 347 comparative trials (no cardiac surgery) compared the incidence of lactic acidosis in patients with diabetes using metformin versus those not using metformin. Similar to our study, a lower incidence of lactic acidosis was found in the metformin group (0.0043% vs. 0.0054%).[21] We further analyzed factors influencing serum lactate levels. The use of On-Pump CABG surgery was independent predictor of elevated serum lactate levels [Table 4]. In the aforementioned case control study, 127 patients with type 2 diabetes underwent isolated CABG, out of these 41 patients (32%) continued taking metformin and 86 patients (68%) took other antidiabetic agents. They demonstrated that the need for vasopressor administration was an independent predictor of lactic acidosis.[15] The data regarding the impact of metformin use on morbidity in surgical patients are scarce. Our study demonstrated that duration of inotropes and length of hospital stay was more common in non-metformin user diabetic patients. Postoperative renal failure was more common in patients with diabetes, whether metformin users or not. This finding is corresponding with other studies that demonstrated that diabetic patients are more prone to develop renal failure in postoperative period. In our study, requirement of dialysis, pneumonia, and length of ICU stay were similar in all the three groups [Table 3]. In a retrospective study by Duncan et al., postoperative outcomes were compared between metformin users and non-users. They evaluated 1,284 diabetic patients who had received metformin within 8–24 h before cardiac surgery. There were no significant differences in overall mortality and immediate postoperative morbidity. There was no case of lactic acidosis during early postoperative period. They found that the frequency of prolonged tracheal intubation and the total duration of mechanical ventilation were less in metformin-treated patients, suggesting a less-complicated postoperative course in metformin users. In fact, the metformin users had overall less morbidities [OR (95% CI) 0.4 (0.2–0.8); P = 0.005], leading the authors to suggest that pretreatment with metformin might have beneficial effects.[10] Manlapaz et al. analyzed the data of 4,528 diabetic patients who underwent cardiac surgical procedures. The patients received metformin within 8–24 h before surgery. Mortality and morbidity were lower in these patients as compared with patients treated with other hypoglycemic agents. This suggests beneficial effect of metformin use.[22] In the study by Nazer et al., there were no differences in clinical outcomes between groups; and higher lactate levels in non-metformin users did not result in adverse postoperative outcome measures.[15]

Our study has certain limitations. Firstly, this is an observational study with groups having variable number of patients. Though we have tried to exclude factors affecting lactate levels to the maximum possible extent, some factors affecting serum lactate levels cannot be ruled out. Secondly, as most of our subjects were males (87.3%), therefore, this study cannot be generalized to the female population. Most important strength of our study is its prospective design with a large number of patients in all the three groups.

In conclusion, when continued till night before CABG surgery, metformin is not associated with significant changes in lactate levels or adverse immediate postoperative complications. Our study does not support the guidance that metformin be discontinued 24–48 h before a major surgery.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, Diamant M, Ferrannini E, Nauck M, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: A patient-centered approach: Update to a Position Statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:140–9. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Colwell JA. Is it time to introduce metformin in the U.S? Diabetes Care. 1993;16:653–5. doi: 10.2337/diacare.16.4.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nisbet JC, Sturtevant JM, Prins JB. Metformin and serious adverse effects. Med J Aust. 2004;180:53–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wiholm BE, Myrhed M. Metformin-associated lactic acidosis in Sweden 1977-1991. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1993;44:589–91. doi: 10.1007/BF02440866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang X, Harmsen WS, Mettler TA, Kim WR, Roberts RO, Therneau TM, et al. Continuation of metformin use after a diagnosis of cirrhosis significantly improves survival of patients with diabetes. Hepatology. 2014;60:2008–16. doi: 10.1002/hep.27199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park J, Hwang SY, Jo IJ, Jeon K, Suh GY, Lee TR, et al. Impact of metformin use on lactate kinetics in patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Shock. 2017;47:582–7. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crowley MJ, Diamantidis CJ, McDuffie JR, Cameron CB, Stanifer JW, Mock CK, et al. Clinical outcomes of metformin use in populations with chronic kidney disease, congestive heart failure, or chronic liver disease: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:191–200. doi: 10.7326/M16-1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mercker SK, Maier C, Neumann G, Wulf H. Lactic acidosis as a serious perioperative complication of antidiabetic biguanide medication with metformin. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1003–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maznyczka A, Myat A, Gershlick A. Discontinuation of metformin in the setting of coronary angiography: Clinical uncertainty amongst physicians reflecting a poor evidence base. EuroIntervention. 2012;7:1103–10. doi: 10.4244/EIJV7I9A175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duncan AI, Koch CG, Xu M, Manlapaz M, Batdorf B, Pitas G, et al. Recent metformin ingestion does not increase in-hospital morbidity or mortality after cardiac surgery. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:42–50. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000242532.42656.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lustik SJ, Vogt A, Chhibber AK. Postoperative lactic acidosis in patients receiving metformin. Anesthesiology. 1998;89:266–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199807000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, Type 2 Diabetes Clinical Guideline 87. [Last accessed on 2018 Apr 22]. Available from: http://www.nice.org.uk/cg87 .

- 13.The Electronic Medicines Compendium Metformin summary of product characteristics. [Last accessed on 2018 Feb 12]. Available from http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/23244/SPC#CLINICAL_PRECAUTIONS .

- 14.The Electronic Medicines Compendium Metformin Summary of Product Characteristics. [Last accessed on 2019 Sep 04]. Available from: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/23244/SPC#CLINICAL_PRECAUTIONS .

- 15.Nazer RI, Alburikan KA. Metformin is not associated with lactic acidosis in patients with diabetes undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery: A case control study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;18:38. doi: 10.1186/s40360-017-0145-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bansal B, Mithal A, Carvalho P, Mehta Y, Trehan N. Medanta insulin protocols in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18:455–67. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.137486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luft D, Deichsel G, Schmulling RM, Stein W, Eggstein M. Definition of clinically relevant lactic acidosis in patients with internal diseases. Am J Clin Pathol. 1983;80:484–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/80.4.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehta RL, Kellum JA, Shah SV, Molitoris BA, Ronco C, Warnock DG, et al. Acute kidney injury network. Acute kidney injury network: Report of an initiative to improve outcomes in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2007;11:R31. doi: 10.1186/cc5713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baradari AG, Habibi MR, Khezri HD, Arabi M, Khademloo M, Jalali Z, et al. Does high-dose metformin cause lactic acidosis in type 2 diabetic patients after CABG surgery? A double blind randomized clinical trial. Heart Int. 2011;6:e8. doi: 10.4081/hi.2011.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salpeter SR, Greyber E, Pasternak GA, Salpeter EE. Risk of fatal and nonfatal lactic acidosis with metformin use in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010:CD002967. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002967.pub3. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002967.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manlapaz MR, Duncan AI, Koch CG, Xu M, Starr NJ. Diabetic patients treated with metformin have decreased pulmonary morbidity following cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2005;103:A32. [Google Scholar]