Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text

Keywords: buprenorphine, employment, opioid use disorder, patient outcome assessment, patient satisfaction

Objective:

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is associated with physical, social, psychological, and economic burden. This analysis assessed the effects of RBP-6000, referred to as BUP-XR (extended-release buprenorphine), a subcutaneously injected, monthly buprenorphine treatment for OUD compared with placebo on patient-centered outcomes measuring meaningful life changes.

Methods:

Patient-centered outcomes were collected in a 24-week, phase 3, placebo-controlled study assessing the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of BUP-XR 300/300 mg (6 × 300 mg) and 300/100 mg (2 × 300 mg followed by 4 × 100 mg) injections in treatment-seeking participants with moderate-to-severe OUD. Measures included the EQ-5D-5L, SF-36v2, Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire, employment/insurance status, and healthcare resource utilization (HCRU). Changes from baseline to end of study were compared across treatment arms, using mixed models for repeated measures.

Results:

Participants receiving BUP-XR (n = 389) versus placebo (n = 98) had significantly greater changes from baseline on the EQ-5D-5L index (300/300 mg: difference = 0.0636, P = 0.003), EQ-5D-5L visual analog scale (300/300 mg: difference = 5.9, P = 0.017; 300/100 mg: difference = 7.7, P = 0.002), and SF-36v2 physical component summary score (300/300 mg: difference = 3.8, P < 0.001; 300/100 mg: difference = 3.2, P = 0.002). Satisfaction was significantly higher for participants receiving BUP-XR 300/300 mg (88%, P < 0.001) and 300/100 mg (88%, P < 0.001) than placebo (46%). Employment and percentage of insured participants increased by 10.8% and 4.1% with BUP-XR 300/300 mg and 10.0% and 4.7% with 300/100 mg but decreased by 12.6% and 8.4% with placebo. Participants receiving BUP-XR compared with placebo had significantly fewer hospital days per person-year observed.

Conclusions:

These results show the feasibility of measuring patient-centered life changes in substance use disorder clinical studies. Participants receiving up to 6 monthly injections of BUP-XR, compared with placebo, reported better health, increased medication satisfaction, increased employment, and decreased healthcare utilization.

Opioid use disorder (OUD) is a neurobehavioral syndrome characterized by continued opioid use despite persistent adverse social, psychological, and/or physical consequences (Nosyk et al., 2011; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The goal of OUD treatment is to support the patient on a path towards recovery, a process leading to a healthy, positive way of life. Therefore, understanding the patient's voice is critical in clinical decision-making (Fowler et al., 2011). Improved health status, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and employment will promote access, adherence, and retention to treatment, which will further encourage patients to continue along the recovery process (Ling et al., 2012).

Buprenorphine, a partial agonist at the mu-opioid receptor, is a treatment option for people with OUD. An injectable depot formulation of buprenorphine represents an alternative to daily sublingual or buccal-dosing regimens. RBP-6000, referred to as BUP-XR, is the first buprenorphine extended-release monthly injection, for subcutaneous use [CIII] (SUBLOCADE, Indivior Inc.) approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (SUBLOCADE, 2018 [package insert]). BUP-XR was shown to produce significantly higher percentage abstinence and treatment success versus placebo; treatment outcomes were consistent across other efficacy endpoints including control of opioid craving and withdrawal symptoms. BUP-XR was safe and well-tolerated and had higher medication satisfaction scores compared with participants who received individual counselling and placebo. Importantly, no compensatory nonopioid illicit drug use was observed with BUP-XR treatment (Haight et al., 2019).

Removing the daily burden of medication management may allow people with OUD to focus more on living a full life. The beneficial effects of a full life can be measured by evaluating outcomes pertaining to HRQoL, employment, and healthcare use.

The use of HRQoL endpoints in OUD treatment programs remains rare (Bray et al., 2017). To date, no randomized controlled trial of OUD treatment has investigated the effect of treatment on recovery. However, a draft guidance document published by the US FDA on developing depot buprenorphine products emphasizes the importance of incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical trials (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018). Measuring patient-centered outcomes in patients receiving treatment for OUD can help clinicians and other healthcare decision-makers assess the impact of interventions on patients’ lives and recovery journey and support cost-effectiveness evaluations of OUD interventions (Nosyk et al., 2011; Bray et al., 2017). We, therefore, prospectively examined patient-centered outcomes including health status, HRQoL, medication satisfaction, healthcare resource utilization (HCRU), as well as employment and health insurance status as part of a trial comparing BUP-XR and placebo.

METHODS

Study Design

This study evaluated patient-centered endpoints obtained during a phase 3, multi-center, randomized, double-blind study, comparing 2 BUP-XR-dosing regimens with placebo (NCT02357901). A centralized institutional review board approved the study protocol. Study participants were adults, aged 18 to 65 years, seeking pharmacologic treatment for moderate or severe OUD (Nosyk et al., 2011; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Additional information on inclusion and exclusion criteria and the study design is published elsewhere (Haight et al., 2019).

After initial screening and buprenorphine transmucosal induction and dose stabilization, study participants received BUP-XR or placebo monthly by subcutaneous injection for up to 24 weeks. Assessments were conducted at various points between the initial screening phase and 26 to 30 days after injection 6 (Table 1). All participants received manual-guided behavioral counselling/individual drug counselling (IDC) at least once per week.

TABLE 1.

Patient-reported Outcome Measures and Schedule of Assessments

| EQ-5D-5L | SF-36v2 | MSQ | HCRU | ESHI | |||

| Range of scores† | Index 0 to 1* | Domains: 0 to 100* | 1 to 7* | NA | NA | ||

| VAS 0 to 100* | PCS and MCS: norm referenced mean 50 (SD 10)* | ||||||

| Schedule of assessment | Week | ||||||

| Screening | Screening (2 weeks) | X | X | X | X | ||

| Buprenorphine and naloxone sublingual film | Induction (3 days) | ||||||

| Run-In | Dose adjustment (4–11 days) | X | X | X | |||

| BUP-XR injection visits† | Injection 1 | 1 | X | X | X | X | |

| Injection 2 | 5 | X | X | ||||

| Injection 3 | 9 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Injection 4 | 13 | X | X | ||||

| Injection 5 | 17 | X | X | ||||

| Injection 6 | 21 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| EOS/ET/safety follow-up | EOS/ET/safety follow-up | 25 | X | X | X | X | X |

*Higher scores indicate better outcomes.

†Assessments were performed before BUP-XR injection.

BUP-XR, buprenorphine extended-release monthly injection, for subcutaneous use [CIII]; EOS, end of study; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol 5D descriptive system, 5-level version; ESHI, employment status and health insurance questionnaire; ET, early termination; HCRU, healthcare resource utilization; MCS, mental component summary; MSQ, Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire; NA, not applicable; PCS, physical component summary; SF-36v2, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, Version 2.

The population for this analysis included participants in the full analysis set (FAS) who had at least 1 baseline patient-centered measurement. The FAS included all participants randomized and allocated to study treatment. Information on the participant characteristics for the FAS as well as safety and efficacy results were previously reported (Haight et al., 2019).

Patient-centered Outcome Measures

Patient-centered outcomes measured in this phase 3 study included the EQ-5D-5L (Herdman et al., 2011), SF-36v2 (Ware et al., 2008), Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ; Vernon et al., 2010), and a customized questionnaire for employment, health insurance, and resource utilization (Table 1). For assessments obtained at an injection visit, the instrument was administered before the injection.

Health status was measured by the EQ-5D-5L (Herdman et al., 2011), which includes a health utility index score calculated based on responses to 5 single-item domains (mobility; self-care; daily activities; pain/discomfort; and anxiety/depression). Respondents rated each domain according to 5 levels of severity (no, slight, moderate, severe, or extreme problems). The index score ranges from 0 (death) to 1 (best health). In addition to this index, a 20-cm visual analog scale (VAS) score was used in which subjects were asked to make a global assessment of their current state of health on a scale from 0 (worst possible health state) to 100 (best possible health state). The EQ-5D-5L was administered at screening, during the run-in phase, and at weeks 1, 9, 21, and 25.

The SF-36v2 (Ware et al., 2008), is a HRQoL instrument composed of 8 multi-item (36 items) domains. These domains can also be combined into norm-based physical (PCS) and mental component summary (MCS) scores, derived from the domain scores. Higher scores indicate better conditions. The SF-36v2 was administered at screening, during the run-in phase, and at weeks 1, 9, 21, and 25.

Medication satisfaction was measured by the MSQ (Vernon et al., 2010), a single-item questionnaire that evaluates satisfaction with medication. The MSQ is a 7-point scale with the following ratings: 1 = extremely dissatisfied, 2 = very dissatisfied, 3 = somewhat dissatisfied, 4 = neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 5 = somewhat satisfied, 6 = very satisfied, and 7 = extremely satisfied. MSQ scores were categorized as satisfied (5–7), neutral (4), or dissatisfied (1–3). The MSQ was administered at weeks 9, 21, and 25.

Employment and health insurance status, based on participant input on a customized questionnaire, were measured at screening, during the run-in phase, and at each injection visit. Healthcare resource utilization (hospitalizations; residential substance-abuse treatment; general practitioner, specialist and counselling visits; and emergency department [ED] visits) was measured at screening, and at each injection visit.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were summarized using descriptive statistics (number of participants, mean, standard deviation, median, minimum and maximum values). Categorical variables were reported as frequency counts (including number missing) and percentage of participants in corresponding categories.

For EQ-5D-5L dimensions, MSQ scores, employment status, and insurance status, absolute values and change from baseline were compared using Cochran-Mantel Hanszel tests. In secondary analyses, change from screening was also presented. Logistic regressions were subsequently used to assess whether there were significant differences between groups in employment at the posttreatment assessment, controlling for baseline value, where baseline was defined as the last nonmissing value before the first subcutaneous injection. For these models, a last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach was also used to input missing values as a sensitivity analysis.

Change from baseline in EQ-5D-5L index, VAS scores, and SF-36v2 PCS and MCS scores were analyzed using a mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) with terms for site, treatment, visit, and treatment-by-visit interaction as factors and baseline value as a covariate. An unstructured correlation structure was assumed for measurements collected across visits. From these models, least-squared means were calculated. A similar approach was used to assess change in outcomes from screening. A post hoc sensitivity analysis was conducted to adjust for differences in patient characteristics observed between completers and noncompleters.

Given the expected differences in follow-up duration, HCRU was analyzed using an incidence-based approach as observed “events” per person-month. An event might represent hospital admission, hospital bed day, ED visit, or outpatient visit. Healthcare resource use was summed across the follow-up period from baseline through the posttreatment assessment visit or early termination for each patient. This was then summed across each cohort and divided by the follow-up time observed in each cohort (measured as the posttreatment assessment date minus randomization date and divided by 336 [ie, 28 × 12] to present per 12 person-months), to assess the rate of each type of HCRU. Rate ratios were calculated as the rate in the BUP-XR treatment arms divided by the rate in the placebo arm, with associated 95% confidence intervals calculated to assess whether there was a statistically significant difference (ie, significant when 1 was not within the confidence interval).

RESULTS

Participant Characteristics

Out of the FAS (n = 489), 487 participants (BUP-XR 300/300 mg, n = 196; BUP-XR 300/100 mg, n = 193; placebo, n = 98) completed at least 1 patient-centered measure at baseline and comprises our analysis sample. At baseline, participants had a mean age of approximately 40 years and were predominantly white, non-Hispanic males (Haight et al., 2019). Participants who completed the study through week 25 (vs noncompleters) had a higher mean age (41.2 vs 37.7 years) and were less likely to be of white race (65.3% vs 79.8% white).

Health Status

Baseline EQ-5D-5L scores were similar across treatment groups. Problems in pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression were most commonly reported. At week 25, significantly fewer participants receiving BUP-XR 300/300 mg (10.0%; P = 0.010) and 300/100 mg (12.7%; P = 0.048) reported problems on EQ-5D-5L mobility compared with placebo (17.9%). Additionally, at week 25, significantly fewer participants receiving BUP-XR 300/300 mg (23.1%; P = 0.010) reported problems with anxiety/depression compared with placebo (43.6%).

The difference in EQ-5D-5L index least squares (LS) mean change from baseline at week 25 for BUP-XR versus placebo was statistically significant for BUP-XR 300/300 mg (P = 0.003) and had borderline significance for 300/100 mg (P = 0.053) compared with placebo (Table 2). The difference in EQ-5D-5L VAS LS mean change from baseline at week 25 for BUP-XR versus placebo was statistically significant for both BUP-XR 300/300 mg (P = 0.017) and 300/100 mg (P = 0.002). These differences in difference results for BUP-XR versus placebo were consistent in direction and significance when measuring change from screening.

TABLE 2.

Change From Baseline and Screening in EQ-5D and SF-36v2 Scores at Week 25 Based on Mixed Model for Repeated Measures

| Placebo | BUP-XR 300/100 mg | Difference Between BUP-XR 300/100 mg and Placebo | BUP-XR 300/300 mg | Difference Between BUP-XR 300/300 mg and Placebo | ||||||

| Measure | LS mean (SE) | P | LS mean (SE) | P | LS mean difference (SE) | P | LS mean (SE) | P | LS mean difference (SE) | P |

| Change from baseline to week 25 | ||||||||||

| EQ-5D | ||||||||||

| Index | −0.05 (0.02) | 0.013 | −0.01 (0.01) | 0.502 | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.053 | 0.02 (0.01) | 0.205 | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.003 |

| VAS | −3.6 (2.2) | 0.090 | 4.1 (1.2) | <0.001 | 7.7 (2.5) | 0.002 | 2.2 (1.2) | 0.057 | 5.9 (2.5) | 0.017 |

| SF-36v2 | ||||||||||

| Physical component summary | −1.8 (0.9) | 0.045 | 1.4 (0.5) | 0.009 | 3.2 (1.0) | 0.002 | 1.9 (0.5) | <0.001 | 3.8 (1.0) | <0.001 |

| Mental component summary | 1.9 (1.2) | 0.133 | 4.2 (0.7) | <0.001 | 2.4 (1.4) | 0.097 | 4.5 (0.7) | <0.001 | 2.6 (1.4) | 0.063 |

| Physical functioning | −1.8 (2.2) | 0.413 | 0.6 (1.3) | 0.638 | 2.4 (2.5) | 0.333 | 3.6 (1.3) | 0.006 | 5.4 (2.5) | 0.030 |

| Role physical | −1.0 (2.9) | 0.737 | 4.9 (1.6) | 0.003 | 5.9 (3.3) | 0.075 | 6.6 (1.6) | <0.001 | 7.6 (3.3) | 0.022 |

| Bodily pain | 1.5 (3.3) | 0.639 | 8.1 (2.1) | <0.001 | 6.6 (3.5) | 0.060 | 8.8 (2.1) | <0.001 | 7.2 (3.5) | 0.038 |

| General health | −6.6 (2.6) | 0.011 | 5.6 (1.5) | <0.001 | 12.2 (2.9) | <0.001 | 5.8 (1.4) | <0.001 | 12.4 (2.9) | <0.001 |

| Vitality | −0.1 (2.8) | 0.985 | 10.7 (1.7) | <0.001 | 10.8 (3.1) | <0.001 | 10.4 (1.7) | <0.001 | 10.4 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Social functioning | 2.6 (3.2) | 0.415 | 8.4 (1.9) | <0.001 | 5.8 (3.5) | 0.102 | 10.2 (1.9) | <0.001 | 7.6 (3.5) | 0.030 |

| Role emotional | 1.8 (2.7) | 0.491 | 3.6 (1.5) | 0.016 | 1.7 (3.1) | 0.572 | 5.6 (1.5) | <0.001 | 3.8 (3.0) | 0.215 |

| Mental health | 4.7 (2.6) | 0.067 | 8.8 (1.5) | <0.001 | 4.1 (2.9) | 0.161 | 9.6 (1.5) | <0.001 | 4.8 (2.9) | 0.095 |

| Change from screening to week 25 | ||||||||||

| EQ-5D | ||||||||||

| Index | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.002 | 0.10 (0.01) | <0.001 | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.050 | 0.12 (0.01) | <0.001 | 0.06 (0.02) | 0.005 |

| VAS | 9.1 (2.3) | <0.001 | 16.7 (1.4) | <0.001 | 7.6 (2.5) | 0.002 | 15.3 (1.4) | <0.001 | 6.3 (2.5) | 0.011 |

| SF-36v2 | ||||||||||

| Physical component summary | 3.2 (0.9) | <0.001 | 5.5 (0.6) | <0.001 | 2.3 (1.0) | 0.025 | 6.6 (0.6) | <0.001 | 3.4 (1.0) | 0.001 |

| Mental component summary | 5.4 (1.3) | <0.001 | 9.8 (0.8) | <0.001 | 4.4 (1.4) | 0.002 | 10.1 (0.8) | <0.001 | 4.7 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Physical functioning | 10.2 (2.6) | <0.001 | 10.0 (1.6) | <0.001 | −0.2 (2.8) | 0.941 | 14.7 (1.6) | <0.001 | 4.5 (2.8) | 0.111 |

| Role physical | 9.7 (3.0) | 0.001 | 17.0 (1.8) | <0.001 | 7.3 (3.3) | 0.027 | 20.2 (1.8) | <0.001 | 10.4 (3.3) | 0.002 |

| Bodily pain | 14.2 (3.2) | <0.001 | 21.1 (2.0) | <0.001 | 6.9 (3.4) | 0.040 | 22.1 (2.0) | <0.001 | 7.9 (3.4) | 0.020 |

| General health | 4.9 (2.5) | 0.053 | 17.6 (1.5) | <0.001 | 12.7 (2.9) | <0.001 | 17.7 (1.5) | <0.001 | 12.8 (2.8) | <0.001 |

| Vitality | 9.4 (2.8) | 0.001 | 21.9 (1.7) | <0.001 | 12.5 (3.1) | <0.001 | 22.2 (1.7) | <0.001 | 12.8 (3.1) | <0.001 |

| Social functioning | 14.7 (3.2) | <0.001 | 23.2 (1.9) | <0.001 | 8.5 (3.5) | 0.015 | 25.6 (1.9) | <0.001 | 10.9 (3.5) | 0.002 |

| Role emotional | 9.3 (2.8) | <0.001 | 15.6 (1.7) | <0.001 | 6.3 (3.0) | 0.039 | 17.4 (1.7) | <0.001 | 8.1 (3.0) | 0.008 |

| Mental health | 11.4 (2.6) | <0.001 | 18.3 (1.5) | <0.001 | 6.8 (2.8) | 0.017 | 19.3 (1.5) | <0.001 | 7.8 (2.8) | 0.006 |

BUP-XR, buprenorphine extended-release monthly injection, for subcutaneous use [CIII]; LS, least squares; SF-36v2, 36-Item Short Form Health Survey, Version 2; VAS, visual analog scale.

Health-related Quality of Life

At baseline, mean SF-36v2 domain scores and PCS and MCS scores were comparable between the active treatment groups and placebo (Supplemental Table 1). The difference in LS means change from baseline at week 25 was statistically significant for BUP-XR 300/300 mg in 6 domains (P < 0.05 for all) and 300/100 mg in 2 domains (P < 0.05 for both) compared with placebo (Table 2). The difference in LS mean change from screening at week 25 was statistically significant in all but the physical functioning domain for both BUP-XR 300/300 and 300/100 mg (P < 0.05 for both) compared with placebo (Table 2).

On average, SF-36v2 PCS and MCS scores for participants treated with BUP-XR improved from baseline and screening, whereas PCS scores for participants treated with placebo declined from baseline (Table 2). The difference in SF-36v2 PCS LS mean change from baseline at week 25 were significantly improved for BUP-XR 300/300 mg (P < 0.001) and 300/100 mg (P = 0.002) compared with placebo (Table 2). The difference in SF-36v2 MCS LS mean change from baseline at week 25 were numerically improved but did not reach statistical significance for either BUP-XR 300/300 mg (P = 0.063) or 300/100 mg (P = 0.097) compared with placebo.

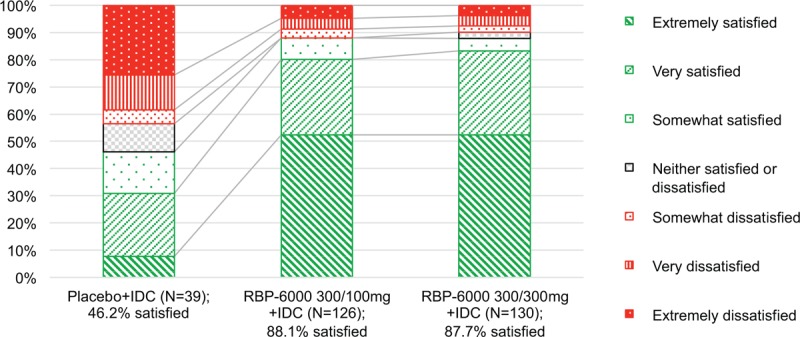

Medication Satisfaction

The proportion of participants who were somewhat satisfied, very satisfied, or extremely satisfied at week 25 was significantly higher for both the BUP-XR 300/300 mg (87.7%, P < 0.001) and 300/100 mg (88.1%, P < 0.001) dosing regimens compared with placebo (46.2%; Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Percentage of subjects who were satisfied or dissatisfied with treatment at week 25a. BUP-XR, buprenorphine extended-release monthly injection, for subcutaneous use [CIII]; IDC, individual drug counselling; MSQ, Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire. aThe MSQ is a 7-point scale with the following ratings: 1, extremely dissatisfied, 2, very dissatisfied, 3, somewhat dissatisfied, 4, neither satisfied nor dissatisfied, 5, somewhat satisfied, 6, very satisfied, and 7, extremely satisfied. MSQ scores were categorized as satisfied (5–7), neutral (4), or dissatisfied (1–3).

Participants receiving BUP-XR 300/300 mg compared with placebo had significantly higher mean MSQ scores at weeks 9 (5.9 vs 4.5, P < 0.001), 21 (6.0 vs 3.6, P < 0.001), and 25 (6.0 vs 3.8, P < 0.001). Mean MSQ scores for participants receiving BUP-XR 300/100 mg were similar to those receiving BUP-XR 300/300 mg at all time points and significantly higher than participants receiving placebo at weeks 9 (5.8 vs 4.5, P < 0.001), 21 (5.9 vs 3.6, P < 0.001), and 25 (6.0 vs 3.8, P < 0.001).

Healthcare Resource Utilization

BUP-XR 300/300 mg participants were followed for a total of 957 person-months in which 7 hospitalizations (22 hospital days), 26 ED visits, and 208 outpatient service visits were observed; BUP-XR 300/100 mg participants were followed for 950 person-months in which 5 hospitalizations (23 hospital days), 44 ED visits, and 267 outpatient service visits were observed. Placebo participants were followed for 325 person-months in which 6 hospitalizations (50 hospital days), 18 ED visits, and 83 outpatient service visits were observed. Participants receiving BUP-XR 300/300 and 300/100 mg had significantly fewer days in the hospital and BUP-XR 300/300 mg significantly fewer ED visits per 12 person-months compared with placebo (Supplemental Figure).

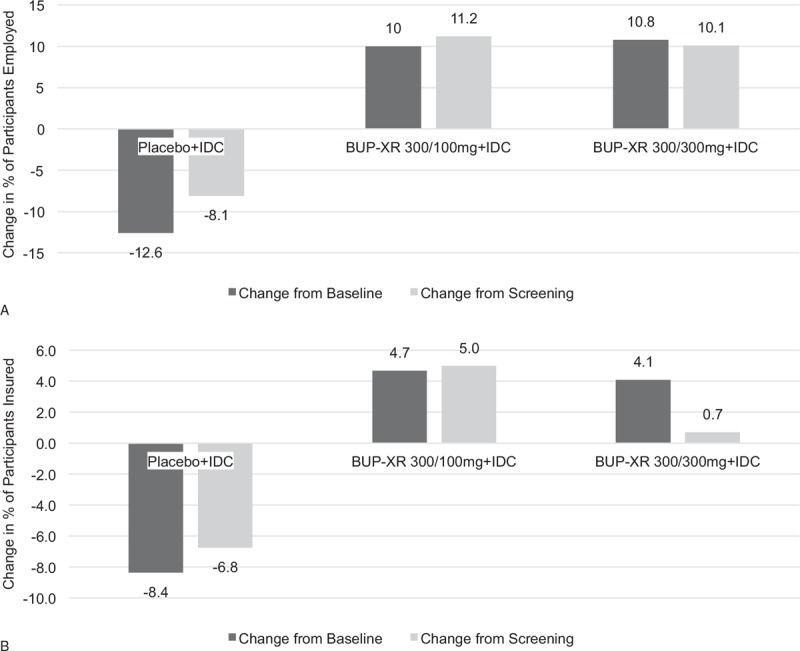

Employment and Health Insurance

At baseline, the percentage of participants who were employed either full- or part-time was lower for the BUP-XR 300/300 mg (40.0%) and 300/100 mg groups (33.7%) compared with placebo (45.9%). Overall, employment rates at week 25 compared with baseline were increased in the BUP-XR treatment groups and decreased in the placebo group (Fig. 2A). Employment rates at week 25 were numerically higher, but not significantly different between the BUP-XR 300/300 mg (50.8%; P = 0.056) or 300/100 mg (43.7%; P = 0.254) and placebo (33.3%) groups. Results remained generally consistent when a LOCF approach was applied in the completer-only analysis and were similar in magnitude when measuring change from employment at screening.

FIGURE 2.

Net change in percentage of participants employed (A) and with health insurance (B) at week 25. BUP-XR, buprenorphine extended-release monthly injection, for subcutaneous use [CIII]; IDC, individual drug counselling.

The mean hours worked per week at baseline for participants receiving BUP-XR 300/300 mg was 14, BUP-XR 300/100 mg 11, and placebo 15. The mean hours worked per week increased significantly by 4.2 hours at week 25 compared with baseline for the BUP-XR 300/300 mg (P = 0.001) and by 3.8 hours for the 300/100 mg (P = 0.004) groups and decreased numerically by 0.4 hours for the placebo group (P = 0.873).

At baseline, 55.9% of participants receiving BUP-XR 300/300 mg, 59.6% receiving BUP-XR 300/100 mg, and 62.2% receiving placebo were insured. At week 25, the proportion insured increased from baseline by 4.1% for the BUP-XR 300/300 mg and 4.7% for the 300/100 mg group and decreased by 8.4% in the placebo group (Fig. 2B). At week 25, more participants receiving BUP-XR 300/300 mg (60.0%; P = 0.579) and 300/100 mg (64.3%; P = 0.262) were insured compared with placebo (53.8%), although the difference did not reach statistical significance. Results remained generally consistent when a LOCF approach was applied to the data.

Sensitivity Analysis

As noted in participant characteristics, there were differences in age and race between completers and noncompleters of the study. A sensitivity analysis adjusting for these characteristics showed similar results for changes from baseline in EQ-5D-5L and SF-36v2 scores (Supplemental Table 2).

DISCUSSION

Our results show the positive effects of up to 6 BUP-XR injections compared with placebo, both administered with IDC, on physical health, employment, treatment satisfaction, and healthcare utilization. From baseline to week 25, participants in the BUP-XR treatment groups showed statistically significant improvement in health status and HRQoL measures. The differences between treatment and placebo groups on both physical and mental outcomes measured using the SF-36v2 were greater than the clinically relevant threshold of 2–3 points reported in the published literature (Ware et al., 2007, 2008). Additionally, our results are similar to those previously published demonstrating the beneficial effect of pharmacologic therapy for OUD on HRQoL (De Jong et al., 2007; Carpentier et al., 2009; Schafer et al., 2009; Oviedo-Joekes et al., 2010; Griffin et al., 2015).

The present study focused on the effect of BUP-XR on HRQoL after induction and dose stabilization with transmucosal buprenorphine as this was the point at which patients were randomized, and (by study protocol) the only patients analyzed were those who remained in the study until this first injection. Regardless of treatment received, mean EQ-5D-5L and SF-36v2 measurements for all participants were typically lower before the transmucosal run-in and stabilization phase than at baseline (ie, before administration of subcutaneous BUP-XR or placebo, Supplemental Table 1) and were similar or only slightly higher than those previously reported (De Jong et al., 2007; Oviedo-Joekes et al., 2010; Griffin et al., 2015). The effect of treatment on patient-centered recovery outcomes were greater in all participants when the effect of buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual film given during the run-in phase was considered. This conceptually shows that participants who completed a brief pharmacotherapy and received at least one session of counselling experience improved outcomes from their pretreatment through end of study regardless of subsequent treatment received, but continuous monthly pharmacotherapy with BUP-XR maintained this improvement in the majority of outcomes.

Whereas improvements from baseline were observed in the BUP-XR groups in general on participant-reported recovery measures, declines in several of these self-reported measures from baseline were seen in those receiving placebo. As all participants received IDC in this study, these findings suggest that after a 2-week run-in treatment period with buprenorphine/naloxone sublingual film, BUP-XR in combination with psychotherapy was superior to psychotherapy alone.

Medication satisfaction was consistently high during the study for participants in the BUP-XR groups. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the MSQ was utilized in trials enrolling participants with OUD. This result is not only statistically significant but appears clinically relevant based on the clinically relevant threshold established in patients receiving antipsychotics for schizophrenia (Vernon et al., 2010).

The ultimate goal of OUD treatment is to support the patient on a path towards recovery, a process leading to a healthy, positive way of life. Therefore, understanding the patient's voice is critical in clinical decision-making (Fowler et al., 2011). Improved health status, QoL, and employment will promote access, adherence, and retention to treatment, which will further encourage patients to continue along the recovery process (Ling et al., 2012). To date, no randomized controlled trial of OUD treatment investigated the effect of treatment on recovery. Measuring HRQoL in patients receiving treatment for OUD can help clinicians and other healthcare decision-makers assess the impact of interventions on patients’ lives and recovery journey and support cost-effectiveness evaluations of OUD interventions (Nosyk et al., 2011; Bray et al., 2017).

The beneficial effects of BUP-XR compared with placebo on the EQ-5D, SF-36v2, and MSQ occurred without a concurrent increase in HCRU. Our study collected data on nonprotocol-driven HCRU. Overall, nonprotocol-driven utilization was low in study subjects potentially reflecting the adequacy of care participants received as part of the clinical trial program. As the cost of nonprotocol-driven medical services was not covered by the clinical trial program, patients and their health insurance plans would be responsible for paying for the services. About 60% of our study participants did not have health insurance at baseline, which likely created a barrier for access to healthcare potentially leading to relatively low utilization during this study. However, both BUP-XR groups had significantly fewer days in hospital compared with the placebo group. The BUP-XR 300/300 mg group also had significantly fewer ED visits compared with the placebo group. These findings are consistent with the results from the Sittambalam study where the use of ED and inpatient services was reduced after treatment with buprenorphine/naloxone in active heroin users compared with the year before treatment (Sittambalam et al., 2014).

There are some limitations of this study. As this trial was powered based on the primary clinical endpoint of abstinence, it may not be powered to detect differences for certain patient-centered outcome measures. The statistical models used assume data were missing at random; nevertheless, the possibility that data were missing not at random exists; indeed, some differences between patients who completed through end of study and those who did not were observed.

The generalizability of our results to a broader population of people with OUD seeking treatment warrants further study. Additional research on the applicability of our observed results in a real-world OUD population is needed.

CONCLUSIONS

Participants receiving up to 6 monthly injections of BUP-XR compared with placebo consistently showed improved health status and HRQoL, increased medication satisfaction, higher employment rates and hours worked, and increased health insurance coverage without incurring additional healthcare utilization.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all participants and investigators who took part in the SUBLOCADE randomized, Phase 3 clinical trial. Additionally, we wish to thank Beth Lesher for her medical writing support.

Footnotes

This study was funded by Indivior Inc.

W.L. is a consultant for Indivior Inc, Alkermes, Camurus/Braeburn, Opiant and Titan Pharmaceuticals. V.R.N., S.M.L., and C.H. are employees of Indivior Inc. N.A.R. was an employee of Indivior Inc. at the time of study conduct. C.T.S. and Y.-C.Y. are employees of Pharmerit International and are consultants for Indivior Inc. V.M. was a clinical investigator for the RBP-6000 clinical trials and consultant for Indivior Inc.

The authors report no conflicts of interest

REFERENCES

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5®). USA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bray JW, Aden B, Eggman AA, et al. Quality of life as an outcome of opioid use disorder treatment: A systematic review. J Subst Abuse Treat 2017; 76:88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier PJ, Krabbe PF, van Gogh MT, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity reduces quality of life in chronic methadone maintained patients. Am J Addict 2009; 18:470–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong CA, Roozen HG, van Rossum LG, et al. High abstinence rates in heroin addicts by a new comprehensive treatment approach. Am J Addict 2007; 16:124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler FJ, Jr, Levin CA, Sepucha KR. Informing and involving patients to improve the quality of medical decisions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011; 30:699–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin ML, Bennett HE, Fitzmaurice GM, et al. Health-related quality of life among prescription opioid-dependent patients: Results from a multi-site study. Am J Addict 2015; 24:308–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haight BR, Learned SM, Laffont CM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a monthly buprenorphine depot injection for opioid use disorder: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res 2011; 20:1727–1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling W, Farabee D, Liepa D, et al. The Treatment Effectiveness Assessment (TEA): An efficient, patient-centered instrument for evaluating progress in recovery from addiction. Subst Abuse Rehabil 2012; 3:129–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosyk B, Guh DP, Sun H, et al. Health related quality of life trajectories of patients in opioid substitution treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend 2011; 118:259–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oviedo-Joekes E, Guh D, Brissette S, et al. Effectiveness of diacetylmorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid dependence in women. Drug Alcohol, Depend 2010; 111:50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer A, Wittchen HU, Backmund M, et al. Psychopathological changes and quality of life in hepatitis C virus-infected, opioid-dependent patients during maintenance therapy. Addiction 2009; 104:630–640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sittambalam CD, Vij R, Ferguson RP. Buprenorphine Outpatient Outcomes Project: can Suboxone be a viable outpatient option for heroin addiction? J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect 2014; 4: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUBLOCADETM [package insert]. North Chesterfield, VA: Indivior Inc., 2018. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Opioid dependence: Developing depot buprenorphine products for treatment guidance for industry, draft guidance. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/ucm/groups/fdagov-public/@fdagov-drugs-gen/documents/document/ucm605227.pdf Accessed May 1, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Vernon MK, Revicki DA, Awad AG, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Medication Satisfaction Questionnaire (MSQ) to assess satisfaction with antipsychotic medication among schizophrenia patients. Schizophr Res 2010; 118:271–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J, Kosinski M, Bjorner J, et al. Determining important differences in scores. User's Manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Kosinski M, Bjorner JB, et al. User's manual for the SF-36v2 Health Survey. Lincoln, RI: Quality Metric; 2008. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.