Abstract

Introduction When planning the treatment of women with gestational diabetes, the current standard approach also takes fetal growth development into account. The treatment of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes mellitus (DM) used to be based exclusively on maternal blood glucose values. This study investigated the impact of including fetal growth parameters in the monitoring of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes mellitus.

Patients/Method 199 pregnant women with type 1 DM were included in a cohort study. The patient population was divided into two study cohorts. In the mBG cohort (n = 94; investigation period: 1994 – 2005) treatment was monitored using only maternal blood glucose (mBG) values; the aim was to achieve standard target glucose values (mean BG < 5.5 mmol/l, postprandial: at 1 h < 7.7 mmol/l, at 2 h < 6.6 mmol/l). In the fUS collective (n = 101, investigation period: 2006 – 2014) fetal growth parameters were additionally included when monitoring treatment from the 22nd week of gestation, and maternal target glucose values were then individually adjusted to take account of fetal growth. This study aimed to investigate the impact of these two different ways of monitoring treatment on perinatal and peripartum outcomes.

Results 91.4% of all patients were normoglycemic at the time of delivery (HbA 1c < 6.7%); 58.9% of patients achieved strict normoglycemia (HbA 1c < 5.7%). No differences were found between the two study cohorts (fUS vs. mBG: HbA 1c < 6.7%: 93.9 vs. 88.4%, n. s.; mean blood glucose (BG): 5.4 ± 0.6 to 6.6 ± 1.1 vs. 5.9 ± 0.7 to 7.4 ± 1.9 mmol/l, n. s.). Patients from the fUS cohort required significantly lower weight-adjusted maximum insulin doses (0.9 ± 0.3 vs. 1.0 ± 0.4 IE/kg bodyweight, p < 0.05). Pregnancy complications occurred significantly less often in the fUS cohort (preeclampsia: 7.1 vs. 20.9%, p = 0.01; premature labor: 4.0 vs. 23.3%, p < 0.001; cervical insufficiency: 0.0 vs. 11.6%, p = 0.001), and there were significantly fewer cases with neonatal hyperbilirubinemia (19.2 vs. 40.7%, p = 0.001). There was no difference in the rates of LGA infants between the two cohorts (21.2 vs. 24.4%, n. s.).

Conclusion Using maternal blood glucose values combined with fetal growth parameters to monitor DM treatment allows therapeutic interventions to be individualized and reduces the risk of maternal and infant morbidity. The metabolism of patients in the fUS cohort was significantly more stable and there were fewer variations in glucose values. It is possible that the detected benefits are due to this metabolic stabilization.

Key words: diabetes mellitus, blood glucose, sonography, complications of pregnancy, fetal outcome

Introduction

Around 6 million people in Germany are known to have type 1 or type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM) 1 . According to the BQS (Bundesgeschäftsstelle Qualitätssicherung gGmbH) evaluation of German perinatal data from 2013, diabetes was present prior to conception in 0.95% (n = 6256) of cases out of 658 735 persons who gave birth 2 .

Women with DM have higher rates of maternal and fetal morbidity. Depending on the quality of maternal metabolic control, higher rates of miscarriage, malformations, premature delivery and preeclampsia have also been reported for this group of pregnant women. Children born to women with type 1 diabetes mellitus have higher rates of macrosomia, a higher risk of shoulder dystocia and higher rates of postnatal adjustment disorders (hyperbilirubinemia, breathing disorders) 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 . In addition, the risk of stillbirth and postnatal infant mortality is higher compared to healthy collectives 10 , 11 .

The DDG has recommended using a metabolic target of almost normal values for at least 3 months prior to conception. HbA 1c should not be more than 0.5 – 1.0% above the respective reference value for the laboratory method used. During the course of pregnancy HbA 1c should be determined every 4 – 6 weeks; target values are the reference values of a healthy population. The target blood glucose values for patients with type 1 DM should be 3.3 – 5.0 mmol/l when fasting, < 7.7 mmol/l at 1 h postprandially, and < 6.6 mmol/l at 2 h postprandially. According to the current guideline, mean blood glucose values, which are calculated using 6 values measured across the course of one day, should be between 4.7 – 5.8 mmol/l 15 , 27 .

The determination of fetal growth parameters and the use of these fetal growth parameters to guide treatment is an established approach when treating women with gestational diabetes 14 . The current recommendations on managing the treatment of pregnant women with manifest pregestational DM include fetal biometry based on ultrasound examinations carried out every 2 – 4 weeks from the 24th week of gestation (GW) in addition to standard diabetic monitoring of the maternal metabolism 15 , 27 . Although studies have shown the benefits of using fetal growth parameters to monitor the treatment of women with gestational diabetes (GDM) as it allows treatment to be individually adjusted, these data are still lacking for women with pregestational DM 12 , 13 . At present, ultrasonographic imaging is used to monitor the fetus and detect possible risk constellations for fetal growth disorders or impaired fetal nutrition. There are currently no studies which have investigated whether target blood glucose values should be adjusted based on changes in the growth curves of fetuses carried by type 1 diabetic women.

The aim of this study was to investigate whether ultrasound measurement of fetal growth parameters, in addition to monitoring the blood glucose values of pregnant women with type 1 DM, could reduce pregnancy complications and improve fetal outcomes.

Patients and Method

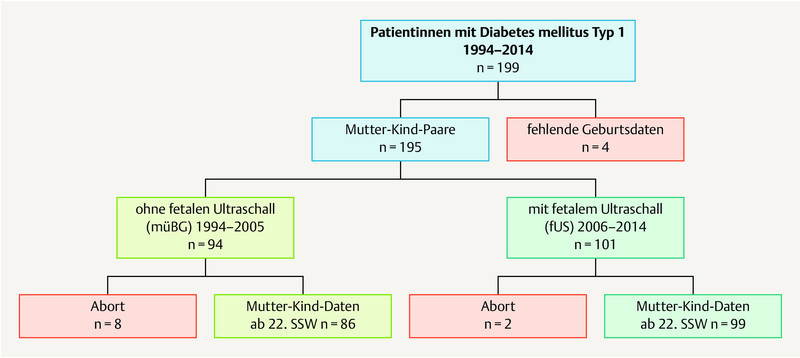

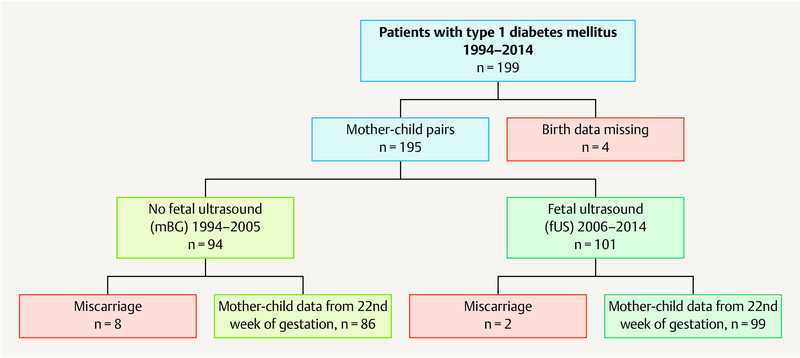

This study was a prospective cohort study (Cohort 2) based on the retrospective collection of data from a comparable (Cohort 1). A total of 199 pregnant women with type 1 DM who were managed by UKJ from 1994 – 2014 were included in the study. After 4 patients were retrospectively excluded as data on the births were lacking, 195 mother-child pairs were available for analysis ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Study population: 199 patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus during pregnancy were included in the study; 4 patients were retrospectively excluded due to a lack of birth data. The data of 195 mother-child pairs were available for analysis. They were subdivided into 2 study cohorts: mBG – patients whose treatment was monitored using only maternal blood glucose values (without fetal ultrasonography), and fUS patients whose treatment management additionally included the monitoring of fetal growth parameters (with fetal ultrasonography). Miscarriages occurred in both study cohorts, meaning that, after the 22nd GW, data from 86 mother-child pairs (mBG cohort) and from 99 mother-child pairs (fUS cohort) was available for analysis.

The study population consisted of 2 cohorts with the following characteristics:

Cohort 1: mBG study collective, n = 94. This study cohort consisted of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes who were treated in the period from January 1994 to December 2005 and monitored using only maternal blood glucose (mBG) values without fetal ultrasound. All of their data was analyzed retrospectively and obtained from archived blood glucose diaries and the data recorded in the electronic patient files EMIL ® .

Cohort 2: fUS study collective, n = 101. This prospective study group consisted of all pregnant women with type 1 DM treated in the period from January 2006 to December 2014; all women in the fUS cohort were monitored and treated according to a clearly defined study protocol which consisted of blood glucose monitoring combined with monitoring based on fetal ultrasound (fUS).

Overall, 5.1% of pregnant women (n = 10) suffered a miscarriage. At the end of the 22nd week of gestation, the data of 86 patients from the mBG cohort and 99 patients from the fUS cohort were available for analysis ( Fig. 1 ).

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Friedrich Schiller University Jena (vote no. 5280-09/17), and all patients gave their written consent to the data collection.

Study/treatment protocol

The maternal blood glucose values of the mBG study cohort were recorded every two weeks using blood glucose diaries and the memory in the measuring devices. The aim was to achieve the following target values throughout the entire pregnancy: mean maternal BG < 5.5 mmol/l (mean of all pre- und postprandial glucose levels measured during the day), postprandial BG: at 1 h < 7.7 mmol/l, at 2 h < 6.6 mmol/l. Insulin doses were constantly adjusted to achieve these therapy goals.

In the fUS study cohort, fetal biometry was carried out from the 22nd week of gestation (GW) in accordance with the DEGUM guidelines for medical specialists. The estimated fetal weight was calculated using the Hadlock IV formula 16 . All ultrasound examinations carried out during the investigation period were done by only two different examiners and were performed in accordance with the hospitalʼs own internal standards. If the increase in fetal abdominal circumference (AC) was above the expected percentile increase and was more than the 75th percentile or dropped to less than the 10th percentile during maternal treatment for diabetes, the target value for maternal blood glucose values was decreased by 0.5 mmol/l or increased by the same amount in cases of AC deceleration.

After the 21st GW, the 4-week arithmetic mean of all maternal blood glucose values was calculated to evaluate maternal metabolic control and compare the study cohorts.

A detailed gynecological and diabetic medical history was taken of each patient when the patient first presented to the UKJ, usually in early pregnancy. Blood pressure, body weight, urine status, complications of pregnancy, insulin doses, and mean pre-/postprandial, minimum/maximum blood glucose was recorded every two weeks. HbA 1c was measured every 4 weeks.

Secondary ailments in the total study population of women with type 1 DM

Ophthalmological examinations were carried out to detect diabetic retinopathy prior to pregnancy, in the 1st – 2nd trimester of pregnancy, and prior to delivery. Diabetic neuropathy was scored using the Neuropathy Symptom Scores (NSS) and the Neuropathy Deficit Scores (NDS).

The diagnosis of diabetic nephropathy was made after testing for albuminuria/proteinuria (examinations done prior to pregnancy/diabetic ID card); the stage of renal insufficiency was evaluated using criteria of the Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI).

Delivery data

Data on the birth were recorded using the obstetric records of the respective hospital where the patient gave birth, and neonatal data were obtained by inspecting the obstetric/neonatal records of the respective hospital.

Voigt birth weight percentile values were calculated using the birth weight, sex and week of gestation at delivery as follows:

< 10th percentile: small for gestational age (SGA)

10th – 90th percentile: appropriate for gestational age (AGA)

> 90th percentile: large for gestational age (LGA)

≥ 95th percentile: macrosomia 17 .

The following neonatal morbidity criteria were evaluated post partum and in the first few days of life:

umbilical arterial pH

Apgar score at 1, 5, and 10 minutes after the birth (appearance [skin color], pulse, grimace response [reflexes] activity [muscle tone], and respiration) 18

respiratory adaptation disorders

malformations

childbirth-related injuries

hyperbilirubinemia: laboratory tests were done if neonates presented with symptomatic metabolic imbalance

Laboratory methods

Maternal blood glucose

All patients self-monitored their blood glucose levels using a pocket glucometer; all self-monitored values were calibrated for plasma prior to inclusion in the evaluation. The measurement accuracy of the glucometers was checked every 14 days by carrying out a parallel measurement with an automatic analyzer.

The completeness of the glucose diary entries was checked by retrieving the blood glucose values stored in the measurement device or by electronic retrieval of the data stored in the measurement devices.

Determination of HbA 1c

Determination of glycosylated hemoglobin A 1c was done using standard certified laboratory methods.

Due to changes in normal ranges, HbA 1c values were adjusted to DCCT or NGSP normal ranges of 5.05 ± 0.5% 19 .

Neonatal laboratory parameters

Bilirubin concentrations;

Neonatal bilirubin was measured using direct photometry. Age-dependent normal ranges were: 2nd day of life: 0 – 130 µmol/l, 3rd day of life: 0 – 165 µmol/l, from 4th day of life: 0 – 200 µmol/l,

Total bilirubin. Age-dependent normal ranges were: 1st day of life < 102.6 µmol/l, 2nd day of life < 171.0 µmol/l, 3rd–5th day of life: 205.2 µmol/l, from 7th day of life < 171.0 µmol/l.

Bilirubin concentrations above the respective age- and method-dependent normal ranges were defined as hyperbilirubinemia.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was done using the statistical software program SPSS for Windows, version 22.0. Normally distributed values are shown as mean ± standard deviation (x±s); non-normally presented values are presented as median [minimum – maximum].

A two-sided probability of error of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Maternal characteristics of the study cohorts

The cohorts did not differ with regard to week of gestation at first consultation, duration of clinical diabetes, age, BMI, or complications of diabetes. A higher percentage of the women in the fUS study cohort were already being treated for diabetes ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 Patient history and clinical findings at the start of pregnancy.

| mBG cohort n = 94 |

fUS cohort n = 101 |

Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consultation with diabetologist prior to pregnancy (%) | 38.5 | 61.5 | p < 0.001 |

| Duration of diabetes at first consultation (years) | 14.8 ± 7.9 [1 – 37] | 14.5 ± 7.8 [0 – 32] | n. s. |

| Age at first consultation (years) | 27.7 ± 5.0 [16 – 40] | 28.8 ± 4.8 [18 – 44] | n. s. |

| First consultation at the center (GW) | 11.1 ± 7.8 [3 – 37] | 12.6 ± 8.9 [3 – 33] | n. s. |

| BMI prior to pregnancy (kg/m 2 ) | 24.1 ± 3.4 [18.4 – 34.9] | 25.0 ± 4.7 [18.3 – 41.7] | n. s. |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 122 ± 13 [94 – 168] | 121 ± 13 [93 – 168] | n. s. |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 76 ± 9 [60 – 106] | 76 ± 10 [52 – 107] | n. s. |

| Hypertension (antihypertensive medication) (%) | 8.5 | 4.0 | n. s. |

| Diabetic nephropathy (%) | 7.4 | 8.9 | n. s. |

| Diabetic neuropathy (%) | 6.4 | 1.0 | p < 0.05 |

| Diabetic retinopathy (%) | 21.4 | 18.8 | n. s. |

Metabolic parameters during pregnancy

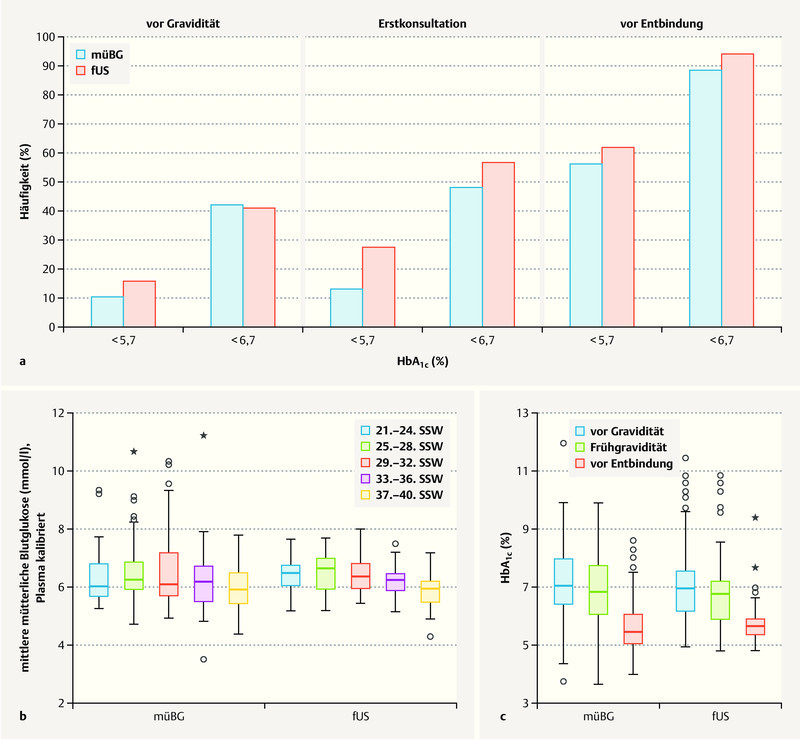

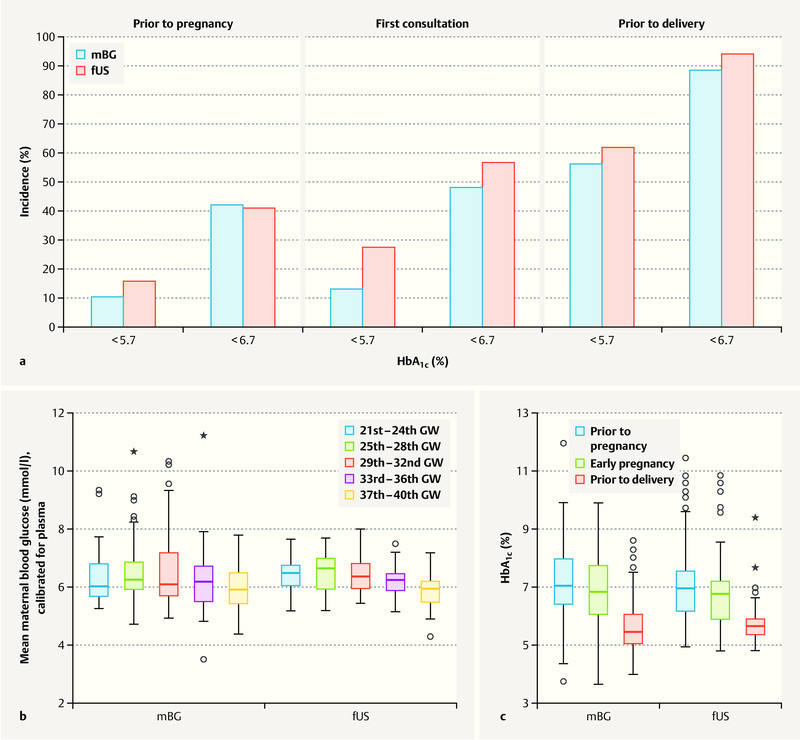

Overall, at the time of delivery 91.4% of patients in the total study population had achieved normoglycemic values of HbA 1c < 6.7% (n = 169; mBG 88.4% vs. fUS 93.9%, n. s.). 58.9% of cases (n = 109; mBG 55.8% vs. fUS 61.6%, n. s.) achieved strict normoglycemic metabolic status, with HbA 1c < 5.7% ( Fig. 2 a ).

Fig. 2.

Changes in blood glucose values of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes. a Strict normoglycemic HbA 1c levels (< 5.7%) and upper target HbA 1c levels (< 6.7%) achieved at various times during pregnancy. Comparison of a cohort of pregnant women whose diabetic control was only checked by monitoring maternal blood glucose levels (mBG, blue) with a cohort of pregnant women whose diabetes was managed by monitoring fetal growth parameters in addition to maternal blood glucose (fUS, red). b Mean blood glucose levels achieved during pregnancy: comparison of two cohorts. c Changes in HbA 1c levels during pregnancy: comparison of two cohorts. (mBG: cohort of pregnant women whose diabetic control was only checked by monitoring maternal blood glucose levels; fUS: cohort of pregnant women whose diabetes was managed by monitoring fetal growth parameters in addition to maternal blood glucose.)

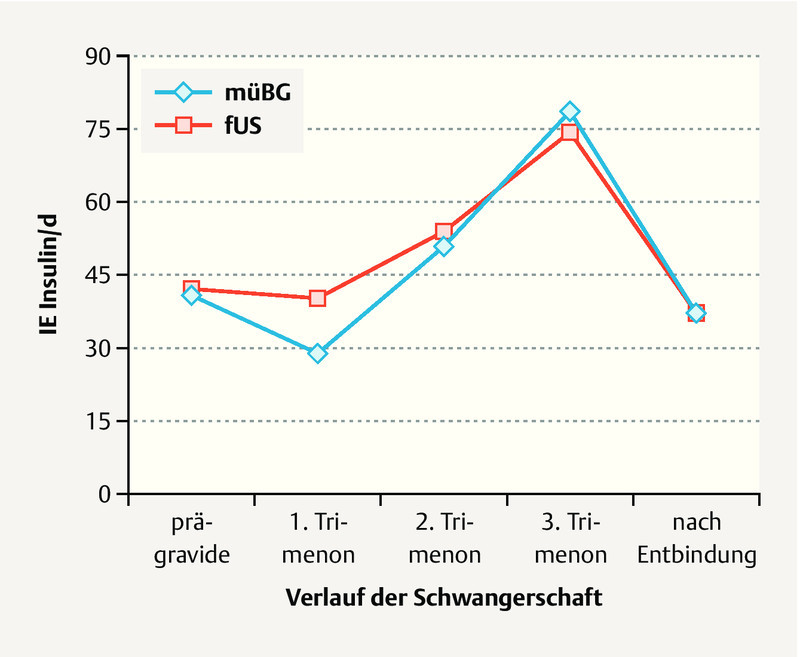

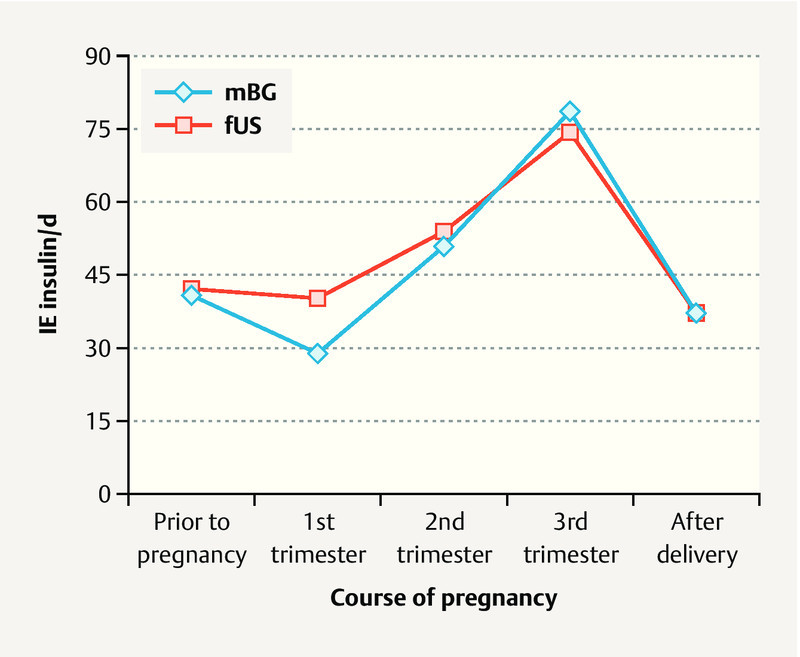

Pregnant women in the mBG study cohort showed no significant difference in mean blood glucose values throughout the course of pregnancy compared to the women in the fUS study cohort. However, glucose variance was lower in the fUS cohort, i.e. their metabolic status was more stable ( Fig. 2 b ). Analysis of HbA 1c showed no differences between the two study cohorts prior to pregnancy (HbA 1c : mBG 7.2 ± 1.3 vs. fUS 7.1 ± 1.3%, n. s.), during early pregnancy (mBG 7.0 ± 1.4 vs. fUS 6.6 ± 1.3%, n. s.) or immediately prior to delivery (mBG 5.8 ± 1.1 vs. fUS 5.7 ± 0.8%, n. s.) ( Fig. 2 c ). There was no difference with regard to absolute insulin doses during pregnancy or after giving birth between the two study cohorts ( Fig. 3 ). However, the weight-adapted maximum insulin dose was significantly lower for the fUS cohort (0.9 ± 0.3 vs. 1.0 ± 0.4 IE/kg bodyweight, p < 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Insulin doses during pregnancy in women with type 1 diabetes: comparison of a cohort of pregnant women whose diabetic control was only checked by monitoring maternal blood glucose levels (mBG) with a cohort of pregnant women whose diabetes managed by monitoring fetal growth parameters in addition to maternal blood glucose (fUS).

Maternal morbidity

Preeclampsia, premature labor and cervical insufficiency occurred significantly less often in the fUS cohort. The data are presented in Table 2 .

Table 2 Maternal complications according to treatment: comparison of mBG and fUS cohorts.

| Total study population (%) n = 185 |

mBG cohort (%) n = 86 |

fUS cohort (%) n = 99 |

Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preeclampsia | 13.5 | 20.9 | 7.1 | p = 0.01 |

| Premature labor | 13.0 | 23.3 | 4.0 | p < 0.001 |

| Cervical insufficiency | 5.4 | 11.6 | 0 | p = 0.001 |

| Cesarean section | 57.3 | 54.7 | 59.6 | n. s. |

|

11.9 | 22.8 | 22.2 | n. s. |

|

19.5 | 33.7 | 37.4 | n. s. |

| Surgically assisted vaginal delivery (forceps and VE) | 6.5 | 7.0 | 6.1 | n. s. |

Perinatal data

Infants born to women in the fUS cohort presented significantly less often with postnatal hyperbilirubinemia (19.2 vs. 40.7%; p = 0.001) and also tended to be less likely to have respiratory adjustment disorders (22.2 vs. 30.2%; n. s.). 8.1% of children born to women in the mBG study cohort and 8.2% of children born to women in the fUS study cohort were SGA for gestational age, 24.4 and 21.2% were LGA, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant. Rates of preterm births and rates of umbilical artery pH < 7.2 did not differ between groups ( Table 3 ).

Table 3 Data of infants grouped according to maternal monitoring during pregnancy: comparison of mBG and fUS study cohorts.

| Total n = 185 |

mBG cohort n = 86 |

fUS cohort n = 99 |

Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight (g) [range] | 3400 ± 673 [1710 – 5400] | 3423 ± 698 [1935 – 5400] | 3374 ± 652 [1710 – 5100] | n. s. |

| SGA (%) | 8.2 | 8.1 | 8.2 | n. s. |

| Birth weight > 90th percentile (%)/LGA | 22.7 | 24.4 | 21.2 | n. s. |

| Preterm birth < 37th GW (%) | 24.7 | 26.4 | 23.2 | n. s. |

| Apgar score < 5 (%) | ||||

|

12.2 | 15.9 | 9.1 | n. s. |

|

3.9 | 4.9 | 3.0 | n. s. |

|

1.7 | 1.2 | 2.0 | n. s. |

| Umbilical artery pH < 7.2 (%) | 35.7 | 34.9 | 36.4 | n. s. |

| Hyperbilirubinemia (%) | 29.2 | 40.7 | 19.2 | p = 0.001 |

| Respiratory adjustment disorder (%) | 25.9 | 30.2 | 22.2 | n. s. |

Discussion

The inclusion of fetal growth parameters in the management of pregnant women with type 1 diabetes is not yet part of the standard treatment protocol 15 , 27 . Although the DDG has been recommending since 2006 that supplementary ultrasound examinations be carried out every 2 – 4 weeks in addition to the standard ultrasound examinations required by the German Maternity Guidelines, these additional ultrasound examinations are only used to detect complications of pregnancy. Regular determination of HbA 1c and monitoring of mean maternal blood glucose levels over the course of the pregnancy is recommended to monitor that management of diabetes is adequate 15 , 27 . Our study in a population of 199 women with type 1 diabetes showed that including fetal growth parameters to monitor metabolic status during pregnancy can offer significant benefits to mother and child. Glucose variance was noticeably improved, significantly reducing the rate of stress-associated complications of pregnancy and leading to improved neonatal outcomes due to a reduction in the number of infants with postnatal hyperbilirubinemia.

It should be noted that the pregnant women in the fUS cohort did not achieve normoglycemia more often than the women in the mBG cohort. But compared to the patients in the mBG cohort, glucose variance in patients in the fUS cohort was lower and the weight-adjusted maximum insulin dose was also significantly lower. This suggests a more stable metabolic status with a lower risk of hypoglycemic events. During pregnancy, recurrent hypoglycemic events are particularly stressful for patients with type 1 diabetes. Our data suggest that ultrasound monitoring of fetal growth can be used to confirm the use of less strict therapeutic protocols and that it is possible to reduce the variation in blood glucose levels, despite the lower maximum insulin doses, and achieve a more stable metabolic status.

It was found that stress-associated complications of pregnancy such as preeclampsia and preterm labor occurred significantly less often in the fUS cohort. The risk of preeclampsia is 2 – 4 times higher for pregnant women with type 1 diabetes compared to women without diabetes 20 , 21 , 22 . The rate of preeclampsia in the population investigated in this study was 13.5%, which is 4 times higher than the incidence of 2 – 3% expected for the total study population 2 . However, although the preeclampsia rate of the mBG cohort was 20.9%, which was almost 10 times higher than the normal rate, the rate for the fUS cohort was 7.1% or just 2.5 times higher than the incidence for all of Germany. The rates of premature labor and cervical insufficiency were significantly lower in the fUS cohort. There was no case with cervical insufficiency in the fUS cohort, and the incidence of premature labor in this cohort was 4%, which was practically almost the same as the 3% rate for all of Germany compared to 23.3% in the mBG cohort 2 .

According to the AQUA Institute, neonatal jaundice developed in 0.26% of all neonates in 2013; the rate in the investigated study population was 29.2% 2 . In 2004, Evers et al. reported a comparable hyperbilirubinemia rate of 25.0% for infants born to pregnant women with type 1 DM 4 . Postnatal hyperbilirubinemia was significantly lower in neonates born to mothers whose diabetic management included monitoring using fetal ultrasound parameters. This finding demonstrates a marked improvement in neonatal outcomes, as prolonged newborn jaundice is a common reason for longer stays in hospital after birth. Maternal hyperglycemia results in fetal hyperinsulinemia. Insulin stimulates the growth of fatty tissue, muscle and liver tissue, leading to increased erythropoiesis and accelerated hemolysis. Chronic hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia lead to decreased placental blood flow, resulting in chronic fetal hypoxemia which further increases erythropoiesis. Increased erythropoiesis and hemolysis lead to hyperbilirubinemia in the postnatal period 23 .

A comparison of the parameters used to assess the quality of metabolic control (HbA 1c and mean BG) found no differences between the compared cohorts. Accordingly, the rate of neonates with macrosomia did not differ between the two cohorts. Any explanation for the positive impact of including ultrasound parameters on the rate of neonatal jaundice is therefore only speculative. If placental hypoxia results in increased fetal erythropoiesis and this increase causes prolonged jaundice in the newborn, improved placental blood flow with improved oxygenation of the placenta could conversely prevent an increase in neonatal hematocrit, providing an explanation for the reduced rate of neonatal jaundice. To verify this possible explanation, a future study would need to compare maternal placental perfusion parameters and hematocrit values in fetal umbilical cord blood. These data are not available for the patient population investigated in this study.

The increased incidence of fetal macrosomia, hyperbilirubinemia and respiratory adjustment disorders compared to a normal population, an incidence which persisted despite the improved management of pregnant women with type 1 DM, demonstrates the increased maternal and fetal risk for pregnant women with type 1 DM and justifies intensified maternal and fetal monitoring during pregnancy. Our data show that the inclusion of fetal growth parameters in metabolic monitoring can reduce fetal and maternal morbidity.

Our study has a number of limitations. The incidence of hypoglycemic events was not recorded for both study cohorts. This means that the postulated therapeutic impact and the reduced risk of hypoglycemia remains speculative. Another limitation is that the actual number of women whose diabetic treatment was adjusted based on fetal ultrasound parameters was not recorded. The number of women with inadequate blood glucose control but normal fetal growth parameters whose therapy was not intensified and whose insulin doses were not adjusted is therefore not quantifiable. There are other influencing factors which can be used to stabilize metabolic control; they include the use of new diabetes technologies and the administration of insulin analogs as part of the treatment strategy during pregnancy. It could be assumed that the percentage of patients with insulin pumps and insulin analogs in the later fUS cohort was higher. However, these parameters were not taken into account in our analysis. Moreover, the impact of other medication on changes in metabolic control could not be evaluated in our study, as the use of drugs such as ASA was not recorded. These drugs could have a potential impact on the occurrence of preeclampsia and affect the findings. The only recorded intake of medication was the use of antihypertensive medication during pregnancy, and there were no differences in intake between the two study cohorts.

Even before they became pregnant, significantly more of the patients in the fUS study cohort were receiving regular treatment for diabetes. This difference may be due to the increasing use in recent years of technical devices which support treatment. Studies have shown that using an insulin pump with bolus management can improve treatment by reducing HbA 1c 24 , 25 , 26 . The new treatment options which are based on the use of technical devices require more frequent and closer monitoring by a diabetologist, leading to more regular medical checkups. This has also led to an increased understanding of the disease and how to treat it. This study does not examine to what extent improved diabetic care led to better outcomes.

Conclusions

Despite the extensive medical care available to pregnant women with pre-existing type 1 diabetes, they still have a significantly higher risk of fetal and maternal complications. Including fetal growth parameters in a diabetic management protocol can contribute to better metabolic control as it is based on individual maternal target blood glucose values. More individualized target values mean that therapeutic measures are taken more promptly, which reduces the increased risk of morbidity, in particular the risk of stress-associated complications of pregnancy. Reduced maternal stress in pregnancy is proposed as a possible explanation for this positive effect. Further prospective studies are required to investigate these connections in more depth.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest./Die Autoren geben an, dass kein Interessenkonflikt besteht.

References/Literatur

- 1.Tamayo T, Rathmann W. Update Diabetologie 2012. Epidemiologie und Diagnostik. Diabetologe. 2013;9:365–372. [Google Scholar]

- 2.AQUA AQUA – Institut für angewandte Qualitätsförderung und Forschung im Gesundheitswesen GmbH: Bundesauswertung zum Verfahrensjahr 2013 16/1 – Geburtshilfe Qualitätsindikatoren. Erstellt: 2014. 24/2014010004Online:https://www.sqg.de/downloads/Bundesauswertungen/2013/bu_Gesamt_16N1-GEBH_2013.pdflast access: 18.05.2018

- 3.McGrogan A, Snowball J, de Vries C S. Pregnancy losses in women with Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes in the UK: an investigation using primary care records. Diabet Med. 2014;31:357–365. doi: 10.1111/dme.12332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evers I M, de Valk H W, Visser G H. Risk of complications of pregnancy in women with type 1 diabetes: nationwide prospective study in the Netherlands. BMJ. 2004;328:915. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38043.583160.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang J, Cummings E A, Oʼconnell C. Fetal and neonatal outcomes of diabetic pregnancies. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108 (3 Pt 1):644–650. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000231688.08263.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li S, Zhang M, Tian H. Preterm birth and risk of type 1 and type 2 diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev. 2014;15:804–811. doi: 10.1111/obr.12214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vestgaard M, Sommer M C, Ringholm L. Prediction of preeclampsia in type 1 diabetes in early pregnancy by clinical predictors: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2018;31:1933–1939. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1331429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wylie B R, Kong J, Kozak S E. Normal perinatal mortality in type 1 diabetes mellitus in a series of 300 consecutive pregnancy outcomes. Am J Perinatol. 2002;19:169–176. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-28499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cordero L, Treuer S H, Landon M B. Management of infants of diabetic mothers. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:249–254. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.3.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vääräsmäki M, Gissler M, Ritvanen A. Congenital anomalies and first life year surveillance in Type 1 diabetic births. Diabet Med. 2002;19:589–593. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holman N, Bell R, Murphy H. Women with pre-gestational diabetes have a higher risk of stillbirth at all gestations after 32 weeks. Diabet Med. 2014;31:1129–1132. doi: 10.1111/dme.12502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonomo M, Cetin I, Pisoni M P. Flexible treatment of gestational diabetes modulated on ultrasound evaluation of intrauterine growth: a controlled randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Metab. 2004;30:237–244. doi: 10.1016/s1262-3636(07)70114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kjos S L, Schaefer-Graf U A. Modified therapy for gestational diabetes using high-risk and low-risk fetal abdominal circumference growth to select strict versus relaxed maternal glycemic targets. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:S200–S205. doi: 10.2337/dc07-s216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schafer-Graf U M. Gestational Diabetes – Major New Clinically Relevant Aspects. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2018;78:977–983. doi: 10.1055/a-0707-6697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kleinwechter H, Schäfer-Graf U, Bührer C. Diabetes und Schwangerschaft. Diabetologie und Stoffwechsel. 2014;9:S214–S220. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hadlock F P, Harrist R B, Sharman R S. Estimation of fetal weight with the use of head, body, and femur measurements–a prospective study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;151:333–337. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90298-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Voigt M, Schneider K TM, Jährig K. Analyse des Geburtengutes des Jahrganges 1992 der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 1996;56:550–558. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1023283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apgar V. A proposal for a new method of evaluation of the newborn infant. Curr Res Anesth Analg. 1953;32:260–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group . Nathan D M, Genuth S, Lachin J. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weissgerber T L, Mudd L M. Preeclampsia and diabetes. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15:9. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0579-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knight K M, Thornburg L L, Pressman E K. Pregnancy Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetic Patients as Compared with Type 1 Diabetic Patients and Nondiabetic Controls. J Reprod Med. 2012;57:397–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen D M, Damm P, Moelsted-Pedersen L. Outcomes in type 1 diabetic pregnancies: A nationwide, population-based study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:2819–2823. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.12.2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Negrato C A, Mattar R, Gomes M B. Adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with diabetes. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2012;4:41. doi: 10.1186/1758-5996-4-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aberle I, Zimprich D, Bach-Kliegel B. Continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion leads to immediate, stable and long-term changes in metabolic control. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2008;10:329–335. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orr C J, Hopman W, Yen J L. Long-term efficacy of insulin pump therapy on glycemic control in adults with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2015;17:49–54. doi: 10.1089/dia.2014.0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kolassa R, Mühlen H, Maraun M. Use of Extended Functions of Modern Insulin Pumps. Diabetes, Stoffwechsel und Herz. 2010;19:405–412. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleinwechter H, Bührer C, Hunger-Battefeld W, Kainer F, Kautzky-Willer A, Pawlowski B, Reiher H, Schäfer-Graf U, Sorger M.DDG-Praxisleitlinie: Diabetes und Schwangerschaft 2014. AWMF Online LL Register 057/023Online:https://www.deutsche-diabetes-gesellschaft.de/fileadmin/Redakteur/Leitlinien/Evidenzbasierte_Leitlinien/Eb_Leitlinie_DS_16-12-14_Überarbeitung_Endfassung.pdflast access: 18.05.2018