Abstract

Introduction Foetal macrosomia is associated with various obstetrical complications and is a common reason for inductions and primary or secondary Caesarean sections. The objective of this study is the generation of descriptive data on the mode of delivery and on maternal and foetal complications in the case of foetal macrosomia. The causes and consequences of foetal macrosomia as well as the rate of shoulder dystocia are examined in relation to the severity of the macrosomia.

Patients The study investigated all singleton births ≥ 37 + 0 weeks of pregnancy with a birth weight ≥ 4000 g at the Charité University Medicine Berlin (Campus Mitte 2001 – 2017, Campus Virchow Klinikum 2014 – 2017).

Results 2277 consecutive newborns (birth weight 4000 – 4499 g [88%], 4500 – 4999 g [11%], ≥ 5000 g [1%]) were included. Maternal obesity and gestational diabetes were more common in the case of newborns weighing ≥ 4500 g than newborns weighing 4000 – 4499 g (p = 0.001 and p < 0.001). Women with newborns ≥ 5000 g were more often ≥ 40 years of age (p = 0.020) and multipara (p = 0.025). The mode of delivery was spontaneous in 60% of cases, vaginal-surgical in 9%, per primary section in 14% and per secondary section in 17%. With a birth weight ≥ 4500 g, a vaginal delivery was more rare (p < 0.001) and the rate of secondary sections was increased (p = 0.011). Women with newborns ≥ 4500 g suffered increased blood loss more frequently (p = 0.029). There was no significant difference with regard to the rate of episiotomies or serious birth injuries. Shoulder dystocia occurred more frequently at a birth weight of ≥ 4500 g (5 vs. 0.9%, p = 0.000). Perinatal acidosis occurred in 2% of newborns without significant differences between the groups. Newborns ≥ 4500 g were transferred to neonatology more frequently (p < 0.001).

Conclusion An increased birth weight is associated with an increased maternal risk and an increased rate of primary and secondary sections as well as shoulder dystocia; no differences in the perinatal outcome between newborns with a birth weight of 4000 – 4499 g and ≥ 4500 g were seen. In our collective, a comparably low incidence of shoulder dystocia was seen. In the literature, the frequency is indicated with a large range (1.9 – 10% at 4000 – 4499 g, 2.5 – 20% at 4500 – 5000 g and 10 – 20% at ≥ 5000 g). One possible cause for the low rate could be the equally low prevalence of gestational diabetes in our collective. A risk stratification of the pregnant women (e.g. avoidance of vacuum extraction, taking gestational diabetes into account during delivery planning) is crucial. If macrosomia is presumed, it is recommended that delivery take place at a perinatal centre in the presence of a specialist physician, due to the increased incidence of foetal and maternal complications.

Key words: foetal macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, gestational diabetes

Introduction

The term “foetal macrosomia” describes excessive intrauterine growth which leads to an increased birth weight. The exact definition is inconsistent. In most investigations, the limit is set at a birth weight of ≥ 4000 g, but in some cases also at a weight of ≥ 4500 g 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 . Alternatively, excessive intrauterine growth can also be defined by growth above the 90th percentile (large for gestational age) 1 .

According to the IQTIG – Institute for Quality Assurance and Transparency in Health, 8.9% of all newborns weighed 4000 – 4499 g and 1.2% ≥ 4500 g 6 in 2016 in Germany. In the analysis of the German perinatal survey data 2007 – 2011, no increase in birth weight was seen in Germany in comparison to the years 1995 – 1997 7 .

Relevant risk factors of macrosomia are the previous birth of a macrosomal child, gestational diabetes, particularly in the case of inadequately controlled blood glucose values, maternal obesity, significant weight gain during pregnancy, male sex of the foetus, exceeding ≥ 41 + 0 weeks of pregnancy, as well as multiparity 3 , 4 , 8 , 9 .

An increase in obstetrical complications as well as in maternal and foetal morbidity and mortality in cases of foetal macrosomia have been described in the literature. A major complication which increases with increasing birth weight is shoulder dystocia. In addition to foetal asphyxia, paralysis of the brachial plexus and a humeral fracture can occur as a result 10 .

The other possible complications include increased postpartum bleeding and more severe birth injuries 8 , 11 . Foetal macrosomia also appears to increase the rate of stillbirths and Caesarean sections 2 . In addition, there is presumed to be an association between foetal macrosomia and a lower 5-minute Apgar score, postnatal hypoglycaemia, and foetal asphyxia 2 , 3 , 8 , 12 .

The suspected diagnosis of macrosomia frequently leads to uncertainty on the part of the parents as well as the attending obstetricians regarding possible complications and the suitable mode of delivery. The high degree of inaccuracy of the sonographic weight estimation at term should be taken into consideration, particularly in the case of macrosomal foetuses 5 . Chauhan et al. demonstrated in a review that the likelihood of diagnosing macrosomia was between 15 and 79%. The sonographic weight estimation of a birth weight ≥ 4500 g was particularly unreliable 13 . Medical interventions such as inductions or preventive Caesarean sections to decrease the risks are the subject of controversial debate.

The risk of complications increases with an increasing degree of macrosomia. A U. S. cohort study by Boulet et al. showed that starting at a weight of ≥ 4000 g, delivery complications occur more frequently, however neonatal morbidity increases significantly only starting at a weight of ≥ 4500 g. Neonatal mortality increased at a weight of ≥ 5000 g 3 . Zhang et al. also observed an increase in neonatal morbidity starting at a weight of ≥ 4500 g 2 .

These results illustrate the challenge of counselling expectant parents depending on the sonographic estimated weight in order to avoid unnecessary interventions and uncertainty. It should additionally be clarified which other factors should be taken into account during delivery planning and the extent to which the sonographic estimated weight can be relied on.

The objective of this study is the generation of descriptive data on the mode of delivery as well as on maternal and foetal complications in the case of foetal macrosomia. These data can be used to provide pregnant patients with evidence-based information and for joint decision-making regarding the mode of delivery if foetal macrosomia is suspected. The causes and consequences of foetal macrosomia should be investigated secondarily as a function of their degree of severity for an adverse maternal or child outcome as well as the investigation of the rate of shoulder dystocia in the various weight groups.

Methodology

Patients

All singleton live births ≥ 37 + 0 weeks of pregnancy with a birth weight ≥ 4000 g at Charité University Medicine Berlin were evaluated. Data were extracted from the ViewPoint database (GE Healthcare, Solingen, Germany) and were available for the Campus Charité Mitte for the period 2001 – 2017 and for the Campus Virchow Klinikum for the period 2014 – 2017. Variables which were described in the literature as being influencing factors for macrosomia as well as the starting variables which can be potentially influenced by macrosomia were discussed. Perinatal acidosis was defined as an umbilical artery pH (UApH) of < 7.10. An adverse perinatal outcome was defined based on the criteria for postnatal cooling as a UApH < 7.0, an umbilical artery base excess (UA-BE) < − 16 mmol/l or a 10-minute Apgar value < 5 14 . An adverse maternal outcome was defined as a severe birth injury (grade III or IV perineal laceration), need for an episiotomy or postpartum bleeding ≥ 500 ml 15 .

Statistics

All data were tested for a normal distribution (− 1 < skew > 1). For variables with a normal distribution, mean values ± standard deviations were determined, for variables with non-normal distributions, medians ± interquartile ranges were determined, and for categorical variables, frequencies were determined. Newborns were divided for the subgroup analyses according to their birth weight into three (4000 – 4499 g vs. 4500 – 4999 g vs. ≥ 5000 g) and two (< 4500 g vs. ≥ 4500 g; < 5000 g vs. ≥ 5000 g) subgroups. Differences in risk factors for foetal macrosomia and mode of delivery and in the maternal and foetal outcome between the subgroups were examined for significance in descriptive analyses using Studentʼs t test for continuous variables and χ 2 test or Fisherʼs exact test for categorical variables. P values for all variables were tested bilaterally and statistical significance was defined as p ≤ 0.05. Cases with missing data were excluded for the analysis of the affected variables.

All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0 (IBM, Armonk, New York, USA).

Results

Of 2277 women included with macrosomal children, the children of 2005 (88%) women had a birth weight between 4000 – 4499 g, 249 (11%) between 4500 – 4999 g and 23 (1%) weighed ≥ 5000 g ( Table 1 ). Women with macrosomal children weighing 4500 g or more significantly differed from women with children between 4000 – 4499 g due to an increased incidence of obesity (26 vs. 17%, p = 0.001) and diabetes in pregnancy (9 vs. 4%, p < 0.001). Women with macrosomal children ≥ 5000 g were more frequently ≥ 40 years (22 vs. 7%, p = 0.020) and more frequently multiparous (17 vs. 5%, p = 0.025) ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 Demographic characteristics of the study cohorts, divided according to birth weight.

| Variable | 4 000 – 4 499 g | 4 500 – 4 999 g | ≥ 5 000 g | all | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 005 (88%) | 249 (11%) | 23 (1%) | 2277 | ||

|

(*

n

): Number of missing data for the variable

** Fisherʼs exact test (instead of χ 2 test, if expected n of a group < 5) *** p value based on the Mann-Whitney U test < 4 500 g vs. ≥ 4 500 g. | |||||

| Age ≥ 40 years | 138 (7%) | 18 (7%) | 5 (22%) | 161 (7%) | |

| 156 (7%) | 5 (22%) | 0.020** | |||

| Week of pregnancy | 40.2 (± 1.0) | 40.1 (± 1.1) | 40.2 (± 1.0) | 0.307 | |

| Diabetes | 74 (4%) | 19 (8%) | 6 (26%) | 99 (4%) | 0.000 |

| 25 (9%) | 0.000 | ||||

|

42 (2%) | 6 (2%) | 4 (17%) | 52 (2%) | 0.000 |

|

24 (1%) | 10 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 35 (2%) | |

|

5 (0.2%) | 1 (0.4%) | 0 | 6 (0.3%) | |

|

3 (0.1%) | 2 (0.8%) | 1 (4%) | 6 (0.3%) | |

| Weight prior to pregnancy ≤ 80 kg | 476 (24%) | 77 (32%) | 9 (39%) | 562 (25%) | 0.013 |

| 86 (32%) | 0.005 | ||||

| Obesity (BMI ≥ 30 prior to pregnancy) (* 116 ) | 331 (17%) | 59 (25%) | 8 (35%) | 398 (18%) | |

| 67 (26%) | 0.001 | ||||

| Weight gain during pregnancy (kg) (* 253 ) | 16 (IQR 12 – 20) | 17 (IQR 13 – 21) | 16 (IQR 12 – 21) | 16 (IQR 12 – 20) | 0.103*** |

| Sex, male (* 1 ) | 1 282 (64%) | 168 (68%) | 15 (65%) | 1 465 (64%) | 0.552 |

| 183 (67%) | 0.285 | ||||

| Multipara (* 4 ) | 98 (5%) | 16 (6%) | 114 (5%) | 0.475 | |

| 110 (5%) | 4 (17%) | 0.025** | |||

| Unipara (* 4 ) | 798 (40%) | 86 (35%) | 8 (35%) | 888 (39%) | 0.289 |

| Post-term | |||||

|

781 (39%) | 101 (41%) | 13 (57%) | 895 (39%) | |

|

1 196 (60%) | 145 (58%) | 10 (44%) | 1 351 (59%) | |

|

28 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0 | 31 (1%) | |

| Only spontaneous, vaginal-surgical or sec. section mode of delivery | 1 737 (89%) | 197 (10%) | 16 (1%) | 1 950 | |

| Induction (* 15 ) | 658 (38%) | 84 (44%) | 5 (31%) | 747 (39%) | |

| 89 (43%) | 0.170 | ||||

| Induction method (* 3 ) | |||||

|

198 (30%) | 28 (32%) | 226 (30%) | ||

|

321 (49%) | 45 (51%) | 366 (49%) | ||

|

126 (19%) | 13 (15%) | 139 (19%) | ||

|

5 (1%) | 3 (3%) | 8 (1%) | ||

|

5 (1%) | 0 | 5 (1%) | ||

Mode of delivery

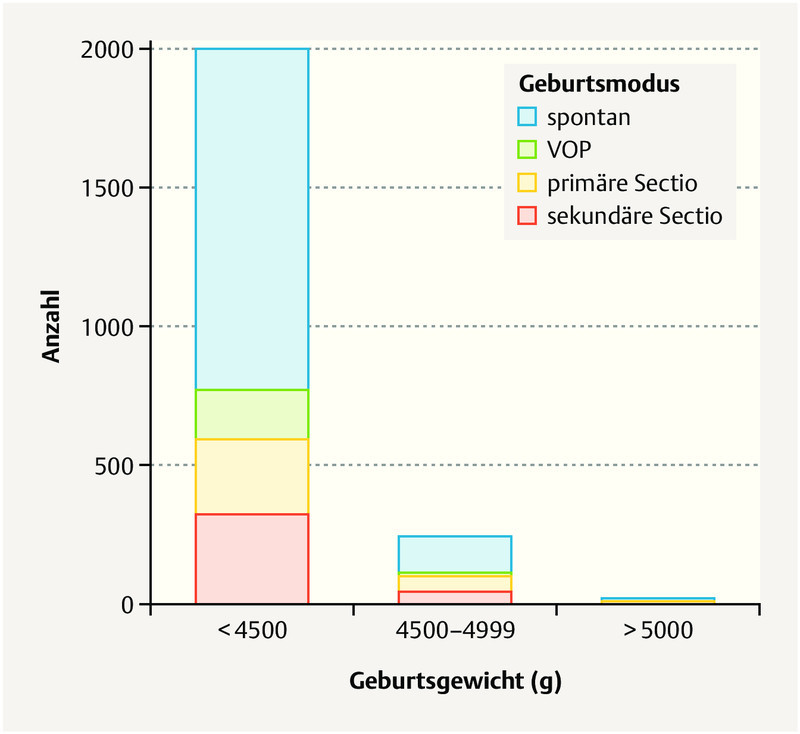

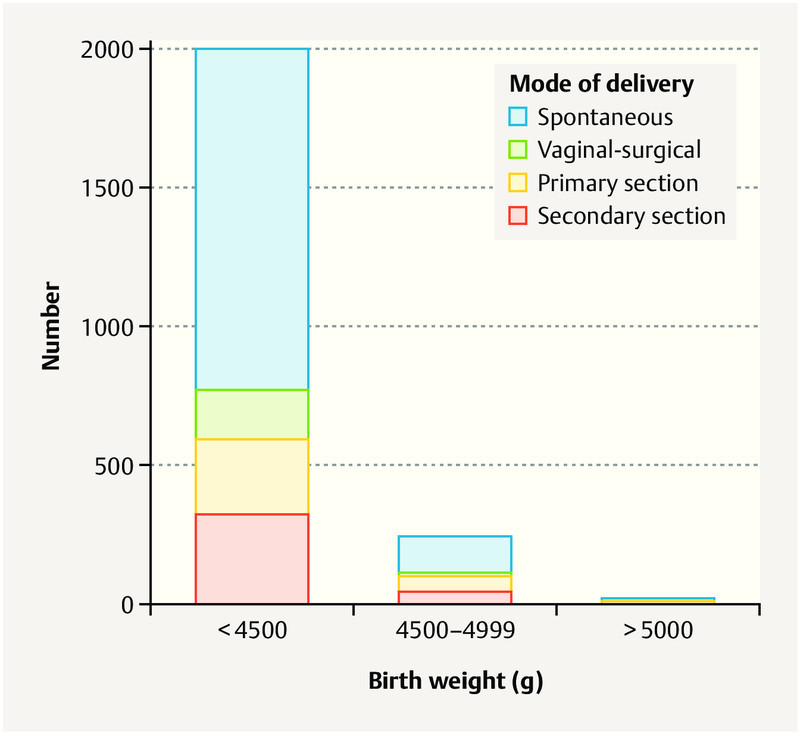

The mode of delivery was spontaneous in 1371 (60%) of all patients, vaginal-surgical in 194 (9%) per primary section in 326 (14%) and per secondary section in 385 (17%) ( Table 2 15 ). Children with a birth weight of 4000 – 4500 g were significantly more frequently delivered vaginally (spontaneous or vaginal-surgical) and the rate of vaginal-surgical deliveries in the case of children ≥ 4500 g was not significantly elevated. The rate of inductions and the method of induction did not significantly differ between the children with a birth weight above or below 4500 g. Excluding primary sections, the rate of secondary sections in children at a weight of ≥ 4500 g was significantly increased as compared to those between 4000 – 4500 g ( Fig. 1 ). The rate of emergency sections was not significantly increased ( Table 2 ). Half (n = 11) of newborns with a birth weight of ≥ 5000 g were born spontaneously.

Table 2 Maternal outcome classified according to birth weight.

| Variable | 4 000 – 4 499 g | 4 500 – 4 999 g | ≥ 5 000 g | all | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(*

n

): Number of missing data for the variable

** Fisherʼs exact test (instead of χ 2 test, if expected n of a group < 5) *** Grade III/IV perineal laceration, bleeding > 500 ml, hysterectomy 15 **** p value based on the χ 2 test < 4 500 g vs. ≥ 4 500 g | |||||

| All modes of delivery | 2 005 (88%) | 249 (11%) | 23 (1%) | 2 277 | |

| Mode of delivery (* 1 ) | 0.000**** | ||||

|

1 229 (61%) | 131 (53%) | 11 (50%) | 1 371 (60%) | |

|

179 (9%) | 15 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 194 (9%) | |

|

268 (13%) | 52 (21%) | 6 (27%) | 326 (14%) | |

|

329 (16%) | 51 (20%) | 5 (23%) | 385 (17%) | |

| Mode of delivery, vaginal (* 1 ) | 1 408 (70%) | 146 (59%) | 11 (50%) | 1 565 (69%) | 0.000 |

| Bleeding (* 95 ) | 0.001 | ||||

|

1 157 (60%) | 118 (48%) | 1 275 (58%) | ||

|

666 (34%) | 108 (44%) | 774 (35%) | ||

|

112 (6%) | 21 (9%) | 133 (6%) | ||

| Adverse maternal outcome*** (* 166 ) | 799 (42%) | 81 (44%) | 15 (71%) | 895 (42%) | 0.023 |

| Only spontaneous or vaginal-surgical mode of delivery | 1 408 (90%) | 146 (9%) | 11 (1%) | 1 565 | |

| Birth injury (* 12 ) | |||||

|

685 (49%) | 71 (50%) | 5 (46%) | 761 (49%) | |

|

450 (32%) | 45 (32%) | 5 (46%) | 500 (32%) | |

|

31 (2%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 33 (2%) | |

|

9 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 | 11 (1%) | |

|

226 (16%) | 21 (15%) | 1 (9%) | 248 (16%) | |

| Birth injury, severe (* 12 ) | 40 (3%) | 4 (3%) | 44 (3%) | 1.000** | |

| Episiotomy (* 9 ) | 326 (23%) | 38 (25%) | 364 (23%) | 0.692 | |

| Blood loss ≥ 500 ml (* 58 ) | 190 (14%) | 26 (19%) | 4 (36%) | 220 (15%) | |

| 30 (21%) | 0.029 | ||||

| Adverse maternal outcome*** (* 58 ) 15 | 256 (19%) | 35 (24%) | 291 (19%) | 0.121 | |

| 286 (19%) | 5 (46%) | 0.043 | |||

| Vaginal-surgical delivery | 178 (13%) | 15 (10%) | 193 (12%) | 0.264 | |

| Only spontaneous, vaginal-surgical or sec. section mode of delivery | 1 737 (89%) | 197 (10%) | 16 (1%) | 1 950 | |

| Sec. section | 329 (19%) | 51 (26%) | 5 (31%) | 385 (20%) | |

| 56 (26%) | 0.011 | ||||

| Emergency section | 22 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 0 | 25 (1%) | 0.749**** |

| Drug-based induction (* 15 ) | 657 (38%) | 89 (43%) | 746 (39%) | 0.165 | |

Fig. 1.

Representation of the mode of delivery in the weight classes 4000 – 4499 g, 4500 – 4999 g and ≥ 5000 g. Primary and secondary sections were performed more frequently with an increasing birth weight.

Neonatal outcome

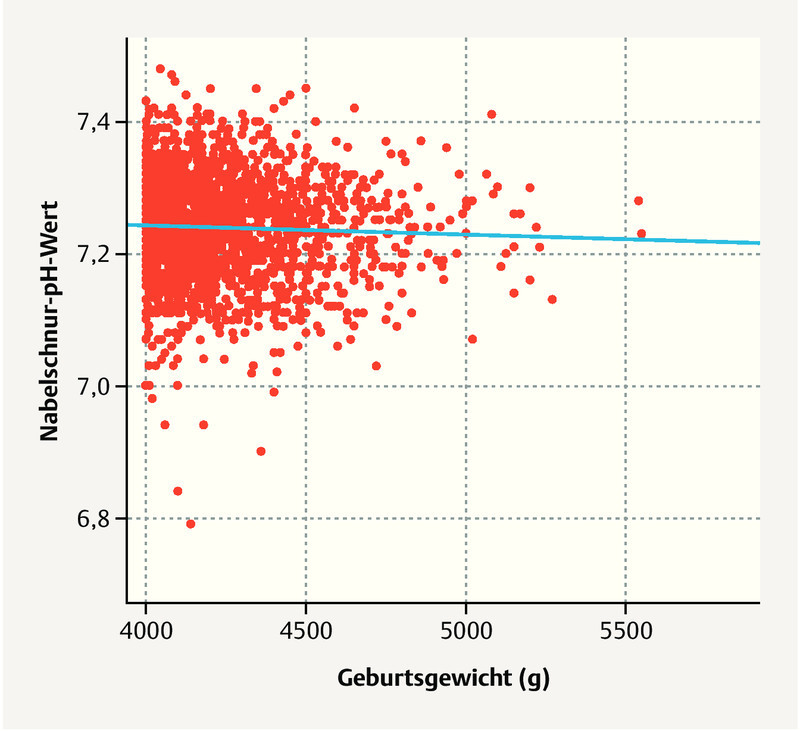

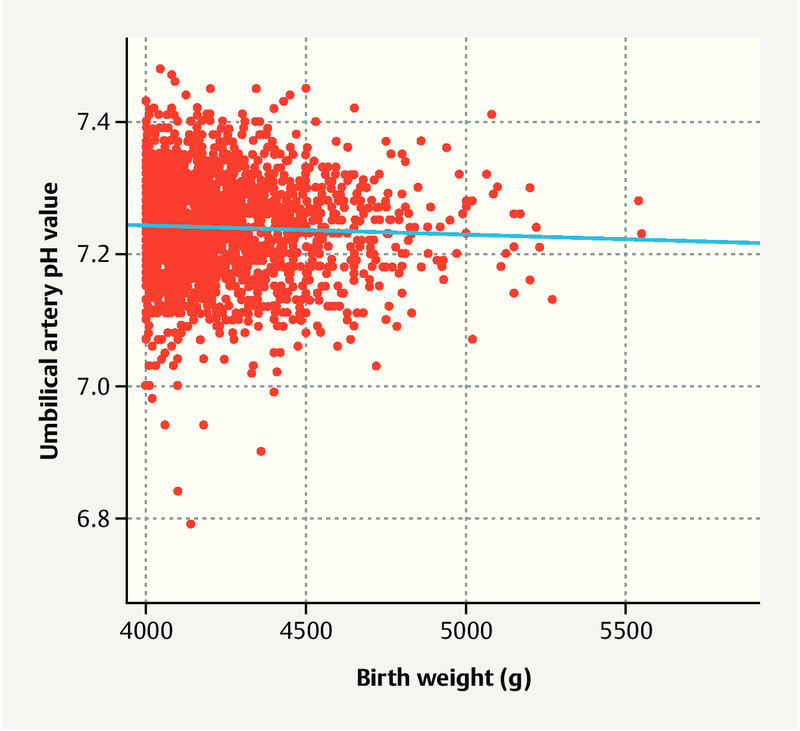

Of the macrosomal children, 57 (2%) had perinatal acidosis; there was no significant difference between children < 4500 g and ≥ 4500 g ( Fig. 2 ). Seven children had a 10-minute Apgar < 5; all children from the group with a weight of 4000 – 4500 g. Children with a birth weight of ≥ 4500 g were transferred postnatally to a neonatology ward far more frequently ( Table 3 14 ). Overall, shoulder dystocia occurred rarely in the case of vaginal delivery (1%) and was noted to occur more frequently at a birth weight ≥ 4500 g. The rate of shoulder dystocia did not significantly differ between women who underwent induction or who had no induction (n = 6 [1.1%] vs. n = 14 [1.4%], p = 0.599). Shoulder dystocia occurred in 2 out of 11 vaginal deliveries > 5000 g ( Table 3 ). There were three cases of brachial plexus paresis and one humeral fracture in a total of 20 cases of shoulder dystocia.

Fig. 2.

UA-pH depending on birth weight. No difference in the various weight groups was observed.

Table 3 Foetal outcome divided according to birth weight.

| Variable | 4 000 – 4 499 g | 4 500 – 4 999 g | ≥ 5 000 g | all | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

(*

n

): Number of missing data for the variable

** Fisherʼs exact test (instead of χ 2 test, if expected n of a group < 5) *** Apgar 10 min < 5, pH < 7, BE < −16 mmol/l (corresponding to the cooling criteria: 14 ) | |||||

| All modes of delivery | 2 005 (88%) | 249 (11%) | 23 (1%) | 2277 | |

| 10-Minute Apgar < 5 (* 23 ) | 7 (0.4%) | 0 | 7 (0.3%) | 1.000** | |

| UApH (* 36 ) | |||||

|

1 930 (98%) | 233 (97%) | 21 (96%) | 2 184 (98%) | |

|

41 (2%) | 8 (3%) | 1 (5%) | 50 (2%) | |

|

7 (0.4%) | 0 | 0 | 7 (0.3%) | |

| UApH < 7.1 (* 36 ) | 48 (2%) | 6 (2%) | 0.885 | ||

| BE < −16 mmol/l (* 154 ) | 7 (0.4%) | 1 (0.4%) | 8 (0.4%) | 1.000** | |

| Transfer to neonatology (* 22 ) | 194 (10%) | 39 (16%) | 7 (33%) | 240 (11%) | |

| 46 (18%) | 0.000 | ||||

| Adverse perinatal outcome*** (* 24 ) | 14 (1%) | 1 (0.4%) | 15 (1%) | 1.000** | |

| Only spontaneous or vaginal-surgical mode of delivery | 1 408 (90%) | 146 (9%) | 11 (1%) | 1 565 | |

| Shoulder dystocia | 12 (0.9%) | 6 (4%) | 2 (18%) | 20 (1%)* | |

| 8 (5%) | 0.000** | ||||

Maternal outcome

133 women (6%) suffered blood loss of ≥ 1000 ml, whereby women with children ≥ 4500 g did not demonstrate increased blood loss significantly more frequently. However, following vaginal delivery, women with children ≥ 4500 g suffered a blood loss of ≥ 500 ml far more frequently.

In the case of a vaginal delivery, 44 women experienced a serious birth injury (grade III/IV perineal laceration: 33 [2%], cervical laceration 11 [1%]) and 364 (23%) underwent episiotomy, whereby there was no significant difference in each case between a birth weight of < 4500 g and of ≥ 4500 g ( Table 2 ).

Discussion

Foetal macrosomia is one of the most common complications in pregnancy.

Our results show that an increasing birth weight is associated with an increase in obstetrical complications, whereby the risk of severe complications, such as shoulder dystocia with potentially long-term damage, is significantly increased at a weight ≥ 4500 g. Nevertheless, even at a birth weight ≥ 4500 g, vaginal delivery was the most common mode of delivery and was possible without complications in the majority of cases.

In accordance with already published data, maternal obesity, diabetes in pregnancy, multiparity and maternal age correlate with an increasing birth weight 3 , 8 . In our collective, there was no difference between the various groups with regard to maternal weight gain during pregnancy. However, a meta-analysis from 2016 showed that excess weight gain can lead to an increased risk of foetal macrosomia 4 . Since this is a risk factor which can be influenced, providing information to the pregnant patients as well as regular weight checks in accordance with the maternity guidelines are relevant.

Our study demonstrates a significantly increased risk of shoulder dystocia at a birth weight of ≥ 4500 g (5%) versus a weight of 4000 – 4499 g (0.9%). In 20 newborns, brachial plexus paresis occurred in three cases and a humeral fracture occurred in one case.

In two of the newborns with brachial plexus paresis, the shoulder dystocia was able to be resolved using the McRoberts manoeuvre and suprasymphyseal pressure. In the third case, the newborn was able to be delivered only after the additional use of the Rubin manoeuvre.

With regard to data already published, the occurrence of shoulder dystocia in our collective is comparatively low. However, the frequency is indicated with a large range (1.9 – 10% in the case of 4000 – 4499 g, 2.5 – 20% in the case of 4500 – 5000 g and 10 – 20% in the case of ≥ 5000 g), which can possibly be attributed to the inconsistent definition and individual estimation 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 . Shoulder dystocia is diagnosed in our clinic if, after the birth of the childʼs head, the head retracts back into the vulva-perineal region in a “turtle” phenomenon and, despite traction in a dorsal and caudal direction, the anterior shoulder can only be delivered through further manoeuvres 21 .

If gestational diabetes is present, the risk is additionally significantly increased 22 . A possible cause for our low rate could be the similarly low prevalence of gestational diabetes in our collective (4% in the case of a foetal weight of 4000 – 4499 g, 9% in the case of a weight of ≥ 4500 g).

The significant increase in the risk of shoulder dystocia in the case of maternal gestational diabetes, induction of delivery, and a vaginal-surgical delivery should be taken into account 16 .

A risk stratification of the pregnant women (e.g. avoidance of vacuum extraction, taking gestational diabetes into account during delivery planning) is crucial in order to avoid this complication.

In this investigation, the occurrence of perinatal acidosis in the case of a higher birth weight was not significantly increased. However, newborns ≥ 4500 g were more frequently transferred to the neonatology intensive care unit. Other studies saw a significant increase in neonatal morbidity at a weight of ≥ 4500 g. At a weight of 4000 – 4500 g, no 2 or only a minor increase 3 in neonatal morbidity versus normosomal newborns was observed.

Maternal complications occurred more frequently than foetal complications.

In vaginal deliveries, women with newborns ≥ 4500 g more frequently experienced increased blood loss than women with newborns between 4000 – 4499 g. Therefore, following the birth of a macrosomal child, bleeding prophylaxis using misoprostol or a long-term oxytocin infusion should be considered, along with the active management of the postpartum period by means of oxytocin, as recommended by the WHO 23 .

A vaginal delivery was the most common mode of delivery in all groups. However, the proportion of vaginal deliveries decreased in the case of a birth weight ≥ 4500 g and the proportion of secondary sections increased.

If macrosomia is suspected in a foetus, the question of the optimal mode of delivery arises in clinical practice. There is currently no general recommendation regarding the sonographic estimated weight at or above which an induction or primary section is advisable. During the consultation, the limited meaningfulness of the sonographic weight estimation, particularly in the case of macrosomal foetuses, should also be considered 13 . In a Cochrane analysis from 2016, an induction in the case of foetal macrosomia had no effect on the rate of sections. However, an induction reduced the birth weight as well as the occurrence of shoulder dystocia. No effect on the occurrence of plexus injuries could be demonstrated 24 .

In the recently published ARRIVE study, pregnant women who underwent induction starting at 39 + 0 weeks of pregnancy even underwent a section more rarely than in the control group with expectant management 25 .

In the S3 guideline “Gestational diabetes mellitus”, an individual approach with regard to an induction is recommended in the case of gestational diabetes. In principle, however, this should be considered starting at week 37 + 0 of pregnancy, particularly in the case of insulin-dependent diabetes and a foetal weight ≥ 95th percentile. The authors additionally recommend a primary section in the case of an estimated weight of ≥ 4500 g 26 , 27 , 28 . If there is no gestational diabetes, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends a preventive section starting at 5000 g. Induction is not recommended 1 .

In summary, the pregnant patient must be informed in detail of the advantages and disadvantages of the respective mode of delivery. Possible consequences of a primary section with regard to a subsequent pregnancy and delivery should be discussed in particular, such as the increased risk of uterine rupture, placenta praevia, or an abnormally invasive placenta. The individual recommendation should also include aspects such as the course of previous deliveries, the presence of gestational diabetes, the physical constitution and the motivation of the pregnant woman. During the birth, it should be noted that a vaginal-surgical delivery increases the risk of shoulder dystocia 11 . The descriptive data collected in this study can be used in conjunction with other studies as a basis.

One limitation of this study are the low numbers of cases for the groups with a weight of 4500 – 4999 and ≥ 5000 g. For this reason, these were summarised for many subanalyses.

In addition, we did not evaluate any data on normosomal newborns. Therefore no statements on the possible causes of foetal macrosomia can be made.

Because of the retrospective nature of the investigation, the data sets are incomplete to some extent. Due to a change in process data acquisition, only data starting in 2014 at one site were able to be included in the study. Due to the nature of the facility as a level 1 perinatal centre, a selection bias also has to be assumed, such that the evaluation could not be used to determine prevalence.

Conclusion

An increasing birth weight is associated with an increased maternal risk and an increased rate of primary and secondary sections as well as shoulder dystocia, with no differences seen in the perinatal outcome between newborns with a birth weight of 4000 – 4499 g and ≥ 4500 g. By contrast, maternal complications, particularly increased blood loss, were significantly increased in the case of a vaginal birth of a child ≥ 4500 g. Overall, a vaginal delivery was possible without complications in the majority of cases, even in the case of macrosomia. From the data generated and the increased rate of transfers to the neonatology ward, it can be seen that, particularly if high-grade foetal macrosomia is suspected, the delivery should take place in a perinatal centre with the availability of experienced obstetricians, midwives and paediatricians and the pregnant patient must receive individual counselling beforehand.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest./Die Autoren geben an, dass kein Interessenkonflikt besteht.

References/Literatur

- 1.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologistsʼ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics . Practice Bulletin No. 173: Fetal Macrosomia. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128:e195–e209. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X, Decker A, Platt R W. How big is too big? The perinatal consequences of fetal macrosomia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:5170–5.17E8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boulet S L, Alexander G R, Salihu H M. Macrosomic births in the united states: determinants, outcomes, and proposed grades of risk. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1372–1378. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian C, Hu C, He X. Excessive weight gain during pregnancy and risk of macrosomia: a meta-analysis. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s00404-015-3825-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanowski J S, Lanowski G, Schippert C. Ultrasound versus Clinical Examination to Estimate Fetal Weight at Term. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2017;77:276–283. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-102406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institut für Qualitätssicherung und Transparenz im Gesundheitswesen Bundesauswertung zum Erfassungsjahr 2016 12July2017. Online:https://iqtig.org/downloads/auswertung/2016/16n1gebh/QSKH_16n1-GEBH_2016_BUAW_V02_2017-07-12.pdflast access:18January2019

- 7.Voigt M, Wittwer-Backofen U, Scholz R. Analysis of the German perinatal survey of the years 2007–2011 and comparison with data from 1995–1997: neonatal characteristics and duration of pregnancy. Z Geburtshilfe Neonatol. 2013;217:211–214. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1361096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stotland N E, Caughey A B, Breed E M. Risk factors and obstetric complications associated with macrosomia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;87:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ehrenberg H M, Mercer B M, Catalano P M. The influence of obesity and diabetes on the prevalence of macrosomia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:964–968. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gross S J, Shime J, Farine D. Shoulder dystocia: predictors and outcome. A five-year review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:334–336. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herzberg S, Kabiri D, Mordechai T. Fetal macrosomia as a risk factor for shoulder dystocia during vacuum extraction. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30:1870–1873. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1228060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oral E, Cagdas A, Gezer A. Perinatal and maternal outcomes of fetal macrosomia. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2001;99:167–171. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(01)00416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chauhan S P, Grobman W A, Gherman R A. Suspicion and treatment of the macrosomic fetus: a review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:332–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Paediatric Society, Fetus and Newborn Committee . Peliowski-Davidovich A. Hypothermia for newborns with hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Paediatr Child Health. 2012;17:41–46. doi: 10.1093/pch/17.1.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fuchs F, Bouyer J, Rozenberg P. Adverse maternal outcomes associated with fetal macrosomia: what are the risk factors beyond birthweight? BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2013;13:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2393-13-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nesbitt T S, Gilbert W M, Herrchen B. Shoulder dystocia and associated risk factors with macrosomic infants born in California. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:476–480. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70382-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill M G, Cohen W R. Shoulder dystocia: prediction and management. Womens Health (Lond) 2016;12:251–261. doi: 10.2217/whe.15.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turkmen S, Johansson S, Dahmoun M. Foetal Macrosomia and Foetal-Maternal Outcomes at Birth. J Pregnancy. 2018;2018:4.790136E6. doi: 10.1155/2018/4790136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alsunnari S, Berger H, Sermer M. Obstetric outcome of extreme macrosomia. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2005;27:323–328. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30457-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kehila M, Derouich S, Touhami O. Macrosomia, shoulder dystocia and elongation of the brachial plexus: what is the role of caesarean section? Pan Afr Med J. 2016;25:217. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2016.25.217.10050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe Arbeitsgemeinschaft Medizinrecht S1-Leitlinie: Empfehlungen zur Schulterdystokie. Erkennung, Prävention und Management. AWMF 015/024. 2010 (2013 abgelaufen)Online:https://www.dggg.de/fileadmin/documents/leitlinien/archiviert/federfuehrend/015024_Empfehlungen_zur_Schulterdystokie/015024_2010.pdflast access: 17.02.2019

- 22.Langer O, Rodriguez D A, Xenakis E M.Intensified versus conventional management of gestational diabetes Am J Obstet Gynecol 19941701036–1046.discussion 1046-1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization WHO recommendations for the prevention and treatment of postpartum haemorrhage Geneva: WHO; 2012. Online:https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/75411/9789241548502_eng.pdf?sequence=1last access: 12.05.2019

- 24.Boulvain M, Irion O, Dowswell T. Induction of labour at or near term for suspected fetal macrosomia. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000938.pub2. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(05):CD000938. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000938.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grobman W A, Rice M M, Reddy U M. Labor Induction versus Expectant Management in Low-Risk Nulliparous Women. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:513–523. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deutsche Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe Deutsche Diabetes Gesellschaft S3-Leitlinie Gestationsdiabetes mellitus (GDM), Diagnostik, Therapie und Nachsorge, 2. Auflage (2018)Online:https://www.deutsche-diabetes-gesellschaft.de/fileadmin/Redakteur/Leitlinien/Evidenzbasierte_Leitlinien/2018/057-008l_S3_Gestationsdiabetes-mellitus-GDM-Diagnostik-Therapie-Nachsorge_2018-03.pdflast access: 18.02.2019

- 27.Schafer-Graf U M. Gestational Diabetes – Major New Clinically Relevant Aspects. Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2018;78:977–983. doi: 10.1055/a-0707-6697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schäfer-Graf U M, Gembruch U, Kainer F. Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) – Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up. Guideline of the DDG and DGGG (S3 Level, AWMF Registry Number 057/008, February 2018) Geburtsh Frauenheilk. 2018;78:1219–1231. doi: 10.1055/a-0659-2596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]