Abstract

MicroRNAs are involved in the crucial processes of development and diseases and have emerged as a new class of biomarkers. The field of DNA nanotechnology has shown great promise in the creation of novel microRNA biosensors that have utility in lab-based biosensing and potential for disease diagnostics. In this Survey and Summary, we explore and review DNA nanotechnology approaches for microRNA detection, surveying the literature for microRNA detection in three main areas of DNA nanostructures: DNA tetrahedra, DNA origami, and DNA devices and motifs. We take a critical look at the reviewed approaches, advantages and disadvantages of these methods in general, and a critical comparison of specific approaches. We conclude with a brief outlook on the future of DNA nanotechnology in biosensing for microRNA and beyond.

INTRODUCTION TO DNA NANOTECHNOLOGY

Size matters, and sometimes being small has advantages. The field of nanotechnology exploits many of the advantages of being small, and has found applications in many fields including energy conversion, storage devices, tissue engineering, and protective clothing (1–3). Controlling the nanoscale features of materials can impart new macroscopic properties and behaviors. Nanomaterials can be built using top-down approaches by starting with a bulk material and breaking it down to nanoscale sizes (e.g. lithography) or bottom-up by taking smaller building blocks (e.g. macromolecules) and assembling them into nanoscale materials.

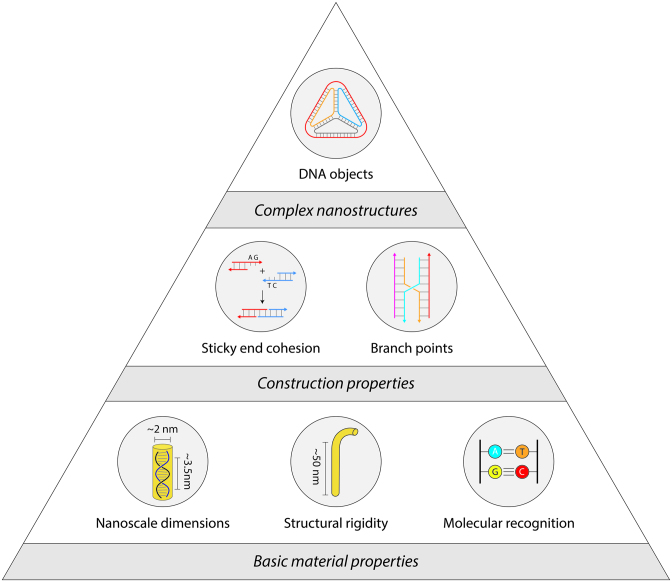

DNA is one such material that can be used for bottom-up construction of nanostructures. The physical characteristics of the molecule (4), well-developed chemistries for functionalization (5), and inexpensive synthesis (6) make DNA a unique and versatile building block. Its intrinsic nanoscale size, tailored sequences and molecular recognition of the canonical Watson-Crick nucleotides enable creation of structures with prescribed geometries (Figure 1). Uniquely, DNA is highly flexible as a single strand and increases its rigidity by ∼50× as a double strand, forming the material basis for using DNA as a nanoscale building block (7).

Figure 1.

Properties of DNA as a construction material.

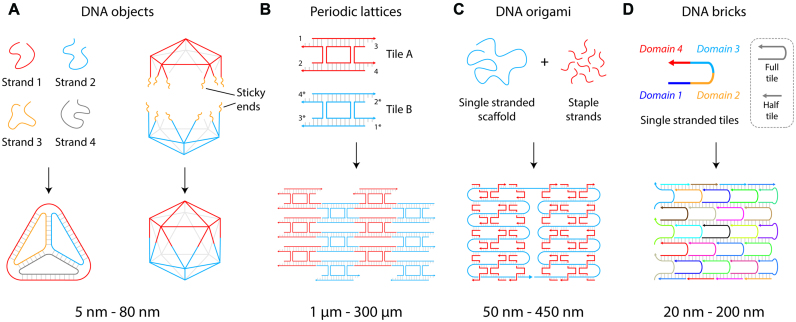

The field of DNA nanotechnology was originally conceived as an idea to scaffold guest molecules, and has expanded to include numerous assemblies and designs in one-, two- and three-dimensions (8,9). Construction using DNA began with branched DNA junctions (10) followed by a variety of DNA objects such as polyhedra (11), prisms (12) and buckyballs (11) (Figure 2A). DNA motifs can be programmed with sticky ends for creating 2D (13) and 3D (14) periodic lattices that are useful as programmable scaffolds for the organization of nanoparticles and biomolecules (15) (Figure 2B). Increasing in complexity, the DNA origami strategy (16) allows creation of larger DNA nanostructures by folding a long single stranded scaffold DNA (usually the viral genome M13) by hundreds of short complementary staple strands into any desired planar, solid or hollow shapes (Figure 2C) (17,18). More recently, the DNA brick strategy uses single stranded DNA tiles that connect through complementary domains to form large DNA assemblies in both 2D (19) and 3D (Figure 2D) (20).

Figure 2.

DNA self-assembly strategies. (A) DNA objects made from designed single strands or pre-assembled DNA motifs. (B) DNA motifs assembled into arrays. (C) DNA origami strategy where a long single strand is folded by short complementary strands. (D) DNA brick strategy to create nanostructures.

Expanding from these design and construction principles, researchers have also developed ‘dynamic’ DNA nanomachines and devices (21,22) that can be programmed to respond to chemical or environmental stimuli (23). Applications of these active DNA nanostructures are now being realized in fields such as drug delivery (24), biomolecular analysis (25), molecular computation (26) and imaging (27). Characteristics of DNA nanostructures have made them especially useful in a biosensing context (28–30). One area of opportunity is in detection of microRNAs, which are small regulatory RNAs important for many aspects of human health. Since nucleic acids are the natural biosensors for microRNAs, it is perhaps not surprising that microRNA detection has in some ways served as a ‘gateway’ into biosensing applications for DNA nanotechnology (31,32).

In this Survey and Summary, we explore and review DNA nanotechnology approaches for microRNA detection. We start with an overview of microRNAs, their relevance as biomarkers, and current detection techniques. Next, we summarize the literature for microRNA detection in three main areas of DNA nanostructures: DNA tetrahedra, DNA origami, and DNA devices and motifs. We take a critical look at the reviewed approaches in the critical analysis and discussion section, exploring advantages and disadvantages of such methods in general, and a critical comparison of specific approaches. We conclude with a brief outlook on the future of DNA nanotechnology in biosensing for microRNA and beyond.

A BRIEF PRIMER ON MICRO RNAS

MicroRNAs are small non-coding RNAs (∼17–25 nucleotides) that regulate gene expression negatively at the post-transcriptional level (33). They are transcribed predominantly as primary transcripts (pri-microRNAs), processed to pre-microRNA in the nucleus, and transported to the cytoplasm for further processing into mature microRNAs. These are then incorporated into RNA Inducing Silencing Complex (RISC) and subsequently bound to 3’ untranslated region (3’UTR) of the target mRNA to cause either translational repression or mRNA degradation (33). From the discovery of the first microRNA (lin-4) in 1993 (34), nearly 2000 microRNAs have been identified in the human genome, predicted to regulate >60% of genes (35). MicroRNAs play essential roles in diverse biological processes including embryogenesis, organ development, proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis, metabolism and homeostasis. Due to these roles, a large body of literature in the past two decades strongly suggests that microRNAs have a huge potential to be developed as novel therapeutics and diagnostic biomarkers for many diseases.

MicroRNAs as new generation biomarkers

Biomarkers should provide critical information of normal physiological states or pathological processes. An ideal biomarker should be stable, easy to obtain by non-invasive procedures, detectable by simple and inexpensive methods in early stage of a disease condition, and non-overlapping with other diseases. MicroRNAs mostly fit these criteria to serve as preferred biomarkers. They can be collected from biofluids including blood, urine, saliva, tears, and other bodily secretions and maintain stability within microvesicles such as exosomes, microparticles and apoptotic bodies (36). Several recent studies have shown examples where microRNAs can be detected in earlier stages of diseases (37). Differential expression of microRNAs can also be found in normal and diseased cells and tissues, serving as useful biomarkers for different cellular events and disease diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment monitoring. These exceptional features of microRNAs have attracted researchers from almost all areas of human diseases to identify and validate unique microRNA signatures as potential disease biomarkers.

MicroRNA expression level is dysregulated in diverse diseases including cancers, neurological disorders, muscle degenerative diseases, cardiovascular disorders, diabetes and viral infections (Table 1). Invariably, in almost every disease, multiple microRNAs display altered (increased or decreased) expression and their expression levels vary significantly. In human esophageal adenocarcinoma, miR-205 is upregulated by 15-fold whereas miR-27a is increased by nearly 2-fold (38). In the opposite direction, miR-143 is downregulated by ∼15-fold whereas miR-424 decreased by ∼2-fold (38). Similarly, in ovarian cancer cells, miR-141 is upregulated by 105-fold whereas miR-558 is upregulated by 1.26-fold. In the same cancer cells, miR-370 is downregulated by 100-fold whereas miR-448 downregulated by only 1.2-fold (39). Similar changes of microRNA expression levels is also observed during disease progression (38). However, in some cases, the changes in the expression levels of microRNAs can be very small. For example, in sporadic Alzheimer's disease, these changes range from 0.6- to 1.25-fold (40). Therefore, an accurate, reliable and sensitive detection method will be the pre-requisite for using microRNAs as new generation diagnostic biomarkers.

Table 1.

Misregulation of microRNAs in a sample of human diseases.

| Disease | microRNAs | References |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer | miR-155, miR-17–92, miR-15a, miR-34a, miR-150, miR-195, let-7, miR-26, and miR-29 | (42–44,46,47,63,67–70) |

| Neurological disorder | miR-34a,b,c, miR-125b, miR-133, miR-103, miR-107, miR-132, miR-212, miR-219 | (40,49–54) |

| Cardiac disorder | miR-17, miR-19, miR-21, miR-92a, miR-145, miR-146a,b, miR-155, miR-208a | (37,55–58,71–73) |

| Muscular dystrophies | miR-199a-5p, miR-486, miR-206 and miR-31, miR-1, miR-133, miR-21 | (74–77) |

| Diabetes | miR-24, miR-26, miR-27a, miR-148, miR-182, miR-373, miR-200a, miR-320 | (78–83) |

| Immunological diseases | miR-17–92, miR-155, miR-21, miR-31, let-7i, miR-125b | (84,85) |

| Viral infections | miR-122, miR-141, miR-142–3p, miR-181, miR-323, miR-491, miR-654 | (59–62) |

The vast majority of studies on microRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers are examined in different types of cancer. Since microRNAs control critical cellular processes, aberrant expression of these small molecules leads to development, progression, and metastasis of cancer. It is intriguing that key molecules in the microRNA biogenesis pathway are altered in cancers (41). As suggested by numerous studies, microRNAs can act either as tumor suppressors or oncogenes. A plethora of studies has documented the altered microRNA expressions in various cancer types including leukemia (42), hepatocellular cancer (43), ovarian cancer (44), pancreatic cancer (45), prostate cancer (46), rhabdomyosarcomas (47) and breast cancer (48).

MicroRNAs play prominent roles in nervous system development and neuronal function (49), and some microRNAs are found exclusively in the brain (50). Altered microRNA expressions are associated with defective brain development and numerous neurological disorders including Alzheimer's disease (40), Parkinson's disease (51) and schizophrenia (52). Furthermore, mutations in microRNA processing machineries are linked to abnormal brain development and neurodevelopmental diseases including familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (53) and fragile X syndrome (54). MicroRNAs are also regulators of cardiac development and function (55), and cardiac specific deletion of Dicer (56) or specific microRNAs (57) causes lethality and abnormal cardiac phenotypes. MicroRNA expression is altered in heart diseases including coronary artery disease, cardiac hypertrophy, myocardial infarction, cardiac fibrosis, atrial fibrillation, ischemic cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, and aortic stenosis and heart failure (58). Circulating microRNAs may be more specific and sensitive biomarkers for heart diseases, sometimes discriminating among closely related heart abnormalities (37). In viral infection, microRNAs control viral replication of many well-known viruses including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), Epstein Barr virus (EBV), and hepatitis C virus (HCV) (59),(60). Altered circulating microRNAs have also been documented in patients infected with viruses (61,62).

The above examples are just a few that demonstrate the diagnostic potential of microRNAs, but a number of obstacles remain before these molecules can be used in clinics for disease diagnostics. Most studies have focused on either one or a set of microRNAs in a particular disease condition, but some microRNAs can be changed in a similar direction for many different diseases. For example, miR-21 expression level is altered in several diseases including cardiovascular diseases, inflammation, and several cancers including breast, cervical, colorectal, glioblastoma, liver, lung, pancreatic, and skin (63,64). Therefore, global screening of circulating microRNAs is needed to generate a specific signature of microRNAs for a specific disease or cancer type. Factors such as age, sex, or prior treatment regimens must also be taken into consideration. Data reproducibility is another major issue that may occur from detection methods, standardization of analytical methods, data processing, normalization and optimization (65,66). Thus, the promise of microRNA diagnostics must be tempered with a realism of the challenges that remain before microRNAs can be used as new generation biomarkers for human diseases.

Current microRNA detection methods

The explosion of interest in microRNAs has led to an increased demand for techniques for detecting these molecules sensitively and accurately both in the laboratory and at the point of care. Low abundance and sequence similarities make sensitivity and selectivity especially important to microRNA discovery, analysis, and clinical diagnosis. Additionally, other aspects of detection including reproducibility, time, cost, complexity and sample requirements will be crucial to facilitate the transition of microRNA research from laboratory to clinical practice.

Currently, the most widely used methods for analyzing microRNAs are quantitative reverse transcription PCR (qRT-PCR) (86), Northern blotting (87), in situ hybridization (88), microarray (89) and next-generation sequencing (90). However, these approaches have some limitations and tradeoffs including poor reproducibility with interference from cross-hybridization, low selectivity, insufficient sensitivity, time-consuming steps, the requirement of large amounts of sample, expensive instruments, or specialized skills (Table 2). We have purposely omitted sensitivity limits on the table due to wide variations even within each method. Several of the approaches (qPCR, in-situ hybridization, sequencing, and isothermal amplification) are in principle capable of detecting a single copy, though for amplification-based methods this is rarely achieved in practice. Most of the assays require total RNA amounts in the hundreds of nanograms to single microgram ranges for detection. qPCR in particular has been demonstrated with significantly less material (pg–ng), while Northern blotting typically requires more (at least micrograms). Some of these methods also require microRNAs to be purified and converted to complementary DNA (cDNA), which is then amplified by polymerase reactions. False positives from contamination are problematic and absolute quantification in general is challenging. This is made especially difficult in methods relying on exponential amplification (such as qRT-PCR), since biases and errors are also amplified exponentially. To illustrate this, a hypothetical 3% per cycle bias in a 30 cycle PCR would develop a >2-fold quantitative error, and achieving detection of a 1.2-fold change as described in the previous section would require <1% per cycle bias. As a result, there is a need to develop analytical platforms for the detection and validation of microRNA in complex biological samples and ideally without amplification. Other strategies such as rolling circle amplification (RCA)-based assays (91) and enzymatic assays (92) have recently been developed to improve sensitivity and flexibility of these methods.

Table 2.

Advantages and disadvantages of the current methods used to detect microRNAs.

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| qPCR | Widely used method for sensitivity. | Lack of multiplexing and genome-wide coverage, biases and errors due to exponential amplification. | (86) |

| Northern blotting | Detects non-amplified microRNAs. | Requirement of large amount of starting materials, radioactivity, less sensitive, time consuming, labor-intensive. | (87) |

| In situ hybridization | Spatiotemporal distribution in cells or tissue sections. | Laborious, requires specialized skills and instruments, time consuming, non-specific. | (88) |

| Microarray | Provides genome-wide coverage. | Requires specific probes and specialized equipment, data normalization is difficult and lacks reproducibility among various platforms. | (89) |

| Next generation sequencing | Provides genome-wide coverage, identifies novel microRNAs and SNPs in microRNAs. | Requires specialized equipment, skilled bioinformatician, complicated data analysis. | (90) |

| Isothermal exponential amplification | High sensitivity, efficient signal amplification, does not require thermocycling equipment. | Requires multiple enzymes including a nicking enzyme and probe design is complicated. | (93) |

DNA-BASED NANOSTRUCTURES FOR MICRO RNA DETECTION

Use of nanomaterials in sensor development has been on the rise (94) including nanotechnology-based approaches for the detection of microRNA sequences (95). Among these nanotechnology approaches, various DNA-based nanostructures have been implemented to overcome some limitations of conventional microRNA detection and quantification strategies. Here we focus specifically on this sub-field, necessarily limiting the scope to exclude some DNA-based approaches (eg: molecular beacons (96), DNA-based FRET (97), spherical nucleic acids (98), nanoparticle-hairpin conjugates (99), catalytic self-assembly (100)) as well as nanotechnology approaches using other materials (e.g. nanoparticles, nanotubes, graphene). To simplify the literature survey, we have classified developments into three main categories based on the type of nanostructure: (i) DNA tetrahedra, (ii) DNA origami and (iii) DNA devices and other assemblies. We have also grouped strategies by sensing approach, where the three main categories are electrochemical, optical and microscopy. To maintain clarity and flow, we include performance metrics in a table (Table 3) rather than in the text.

Table 3.

DNA nanostructures used in the detection of different microRNAs.

| Detection method | Mechanism | Limit of detection | Features | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetrahedra | ||||

| Electrochemical | HRP HCR & HRP QD & Methylene blue Copper nanoclusters RCA & AgNP Target recycle & AgNP HRP Poly-HRP DNAzyme Ferrocene |

2 aM (136) 10 aM (105,106) 17 aM (112) 36 aM (111) 50 aM (137) 0.4 fM (138) 1 fM (139) 10 fM (107) 176 fM (108) 10 pM (110) |

Ultra-sensitive detection Multiple validations Point of care potential |

Equipment requirements Complex preparation Need for enzymes (most) |

| Optical (Fluorescence & Luminescence) |

AuNP/Nuclease Disassembly Reconfiguration |

8.4 aM (115) 2 pM (114) 460 pM(113) |

Live cell compatible Multiplexing No amplification |

Equipment requirements Complex preparation (114) Background signal |

| Origami | ||||

| Super resolution microscopy | Patterned tile | 100 fM (122) | Multiplexing No amplification |

Expensive equipment Cumbersome detection |

| Circular dichroism | Dynamic cross | 100 pM (126) | No amplification | Requires CD spectrophotometer Low sensitivity |

| AFM image | Patterned tile Dynamic cross Dynamic box |

not reported (123–125) | No amplification Integrated logic (124) |

Requires AFM Cumbersome detection Low sensitivity |

| Devices and other assemblies | ||||

| Fluorescence | DNA ferris wheel DNA walker Strand displacement |

25 aM (140) 58 fM (130) 80 fM (128) |

No amplification (128) Non-enzymatic (128,140) |

Background signal Complex design (130,140) |

| Luminescence | Disassembly | 4.6 pM (129) | Live cell compatible | Requires confocal microscope |

| Electrochemical | Nanogears DNA walker DNA walker |

0.2 fM (141) 1.51 fM (134) 3.3 fM (135) |

Ultra-sensitive | Expensive equipment Complex design |

| Colorimetric | DNA ferris wheel | 27 fM (0.5 pM naked eye) (133) | Visual detection | Complex design |

| Gel electrophoresis | DNA looping | 130 fM (132) | No amplification Multiplexing Non-enzymatic |

Low scalability |

HRP: horseradish peroxidase

HCR: hybridization chain reaction

QD: quantum dots

RCA: rolling circle amplification

AgNP: silver nanoparticle

AuNP: gold nanoparticle

DNA tetrahedra

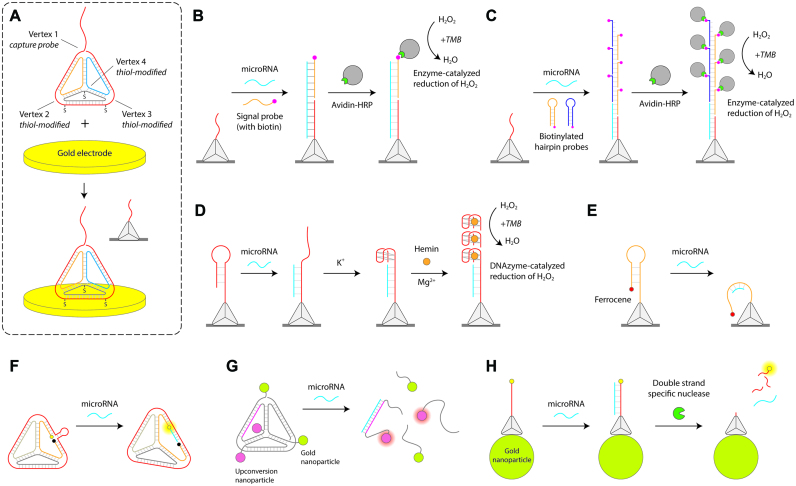

One of the most commonly used DNA nanostructures is a tetrahedron with six double helical edges (101), assembled by annealing four DNA strands with partial complementarity. DNA tetrahedra have good rigidity, excellent cellular permeability and enzyme resistance, and have been used widely in cellular applications and microRNA detection in recent years (30). An especially active area where DNA tetrahedra have been used for microRNA sensing is in electrochemical sensors, developed initially by the Fan group (102). The sensitivity of electrochemical sensors for nucleic acids is limited by the accessibility of target DNA/RNA molecules to probes on the electrode surface due to the reduced mass transport and surface crowding effects (103,104). To address these concerns, Fan and coworkers immobilized DNA tetrahedra on the surface of a gold electrode for electrochemical sensing of microRNA (Figure 3A) (105). Three vertices of the tetrahedron are anchored to the gold electrode through thiol groups and the fourth contains a single stranded extension (capture probe) that is complementary to part of the target microRNA. The detection strategy uses a biotinylated signal probe that is complementary to the remaining part of the target microRNA to recruit avidin–HRP (horseradish peroxidase) conjugates. An electrochemical current is generated by HRP-catalyzed reduction of hydrogen peroxide in the presence of the co-substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (Figure 3B). DNA tetrahedral probes showed enhanced accessibility to target binding compared to linear single stranded probes directly attached on to the surface, thus providing enhanced sensitivity and reproducibility for the assay.

Figure 3.

DNA tetrahedra microRNA biosensors. (A) Design of the DNA tetrahedron with three thiolated vertices to immobilize on gold electrodes for electrochemical detection. The top vertex contains a capture probe (102). (B) DNA tetrahedron for HRP-based electrochemical readout (105). (C) Amplification of HRP-based readout using hybridization chain reaction (106). (D) Guanine nanowire based electrochemical sensing (108). (E) Readout based on proximity of ferrocene to gold surface (110). (F) Fluorescence-based detection using DNA tetrahedron (113). (G) Disassembly of gold nanoparticles and upconversion nanoparticles on microRNA binding (114). (H) Tetrahedron on gold nanoparticles provides a quench-release readout (115).

Variations of this approach have been explored by several different groups. Zuo and co-workers enhanced the electrochemical signal by combining the DNA tetrahedral platform and hybridization chain reaction (Figure 3C) (106). Upon microRNA capture, a hybridization chain reaction is initiated on the gold surface using biotin-modified hairpin substrates. Detection proceeds as before by HRP-mediated electro catalytic signal, but multiple HRP molecules recruited to each probe enhances the limit of detection. Tetrahedron based sensing can be extended to multiple targets by using multiple electrodes each with tetrahedra containing different capture probe sequences for different microRNA targets (107). DNA tetrahedra have also been used to assemble G-quadruplexes on the electrode surface in presence of target microRNA, which in the presence of hemin can act as DNAzymes to oxidize TMB for electrochemical detection (Figure 3D) (108,109).

Some electrochemical approaches have been designed to proceed without the use of the co-substrate TMB. Ding and co-workers used a DNA tetrahedron system to detect lung cancer specific microRNAs by interaction of a ferrocene tag with the gold surface (Figure 3E) (110). The top vertex of the tetrahedron contained a ferrocene tag constrained by a stem-loop configuration to be distant from the gold surface. The stem loop is complementary to the target microRNA, causing it to open the stem and allowing the ferrocene tag to interact with the gold electrode surface giving rise to an electrochemical signal. Yuan and coworkers combined DNA tetrahedra with glassy carbon electrodes to be used as a microRNA sensor using copper nanoclusters to produce electrochemiluminescence (111). Using a photoelectrochemical sensing strategy, Chai and co-workers used a hierarchically assembled DNA tetrahedron (11) as the signal probe (112). The tetrahedron encapsulated CdTe quantum dots (QDs) (a photoactive material) and methylene blue dye (signal enhancer) to provide enhanced photoelectrochemical signal compared to when a DNA duplex containing the dye is used as a signal probe.

Beyond electrochemical sensing, DNA tetrahedra have been used in microRNA detection by changing optical properties to generate signal. The typical approach uses a ‘quench-and-release’ concept to create detection signals, where the assay starts with quenched fluorescence and microRNA binding causes reconfiguration of the structure to cause fluorescence. Xiang and co-workers used a DNA tetrahedron containing a fluorophore and a quencher on one edge connected by a loop that is complementary to the target microRNA (Figure 3F) (113). MicroRNA binding separates the fluorophore and the quencher, increasing the observed fluorescence. Xu and co-workers assembled a DNA tetrahedron with gold nanoparticles at two vertices and upconversion nanoparticles (UCNPs) at the other two vertices (Figure 3G) (114). Due to the close proximity of the gold nanoparticles, the UCNPs do not fluoresce until a target microRNA binds to its complementary region on the tetrahedron and disassembles the nanostructure. Mahboob and co-workers used a DNA tetrahedron with a fluorescent capture probe immobilized onto gold nanoparticles that quench the fluorophore (Figure 3H) (115). The fluorophore is released from the quenching nanoparticle upon microRNA hybridization to the DNA capture probe and subsequent enzymatic cleavage of the DNA in the DNA/RNA hybrid. This process releases the target microRNA to enable several reaction cycles resulting in more fluorophore release. Xie and co-workers designed fluorescent DNA probes attached to gold nanoparticles, additionally using DNA tetrahedra to control the probe surface density (116). Target microRNA binds and releases the fluorophore-containing strand in the duplex, releasing it from the quenching nanoparticle and increasing fluorescence. In another version, Wang and co-workers used DNA tetrahedral probes on gold electrodes and combined it with gold nanoparticles to detect microRNAs using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) (117). In this strategy the SPR signal can further be enhanced by deposition of gold on the nanoparticles.

While DNA tetrahedra have become the dominant polyhedral shape in DNA nanotechnology (and thus the focus of this section), there are a few examples of other shapes that have been used for sensing as well. For example, DNA cubes are used to enhance HCR-based signals by spatial confinement of capture probes within these DNA nanostructures (118). In addition, other DNA objects such as octahedra (119) and prisms (120) used for detection of mRNA and viral nucleic acids have the potential to be applied toward microRNA detection.

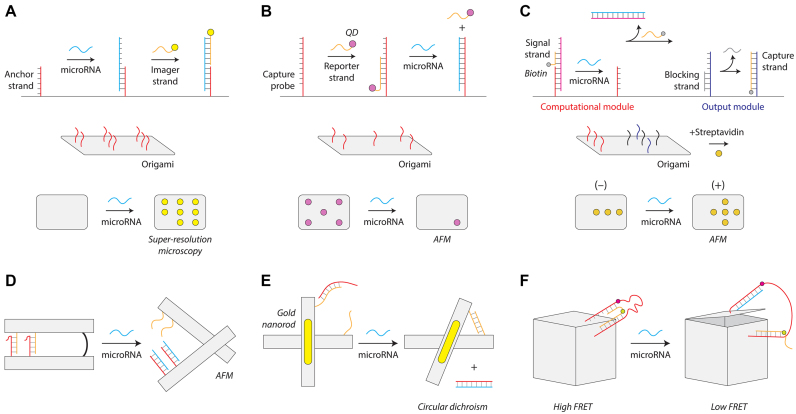

DNA origami

Another major category of DNA nanostructures for microRNA biosensing are those based on DNA origami (16). One general strategy, first pioneered by Yan and colleagues (121), is to use a 2D DNA tile with single-stranded extensions at discrete locations that can be imaged by atomic force microscopy (AFM) or fluorescence microscopy. In one such approach, Dai and co-workers detected microRNAs using point accumulation for imaging in nanoscale topography (DNA-PAINT) (122). Their 2D DNA origami tile was designed with single-stranded capture probes complementary to part of the target microRNA (Figure 4A). They used fluorophore-tagged single stranded DNA (ssDNA) probes to bind to the remaining portion of the target microRNA to enable detection using super-resolution fluorescence microscopy. The authors demonstrated multiplexed detection of eight different microRNAs on a single DNA origami tile, and speculated that the approach could potentially scale to over one hundred. In a different approach, Li and co-workers used AFM imaging to detect microRNAs at locations on a 2D DNA origami tile (Figure 4B) (123). Single stranded capture probes complementary to the target microRNA are partly hybridized with a biotinylated reporter strand to recruit streptavidin-coated quantum dots that can be imaged using AFM. The target microRNA removes the reporter strand and quantum dot through toehold-mediated strand displacement and a reduction of quantum dots on the DNA tile is visualized by AFM. Integrating logic into this strategy, Song and colleagues added a ‘computational module’ into a DNA tile for the detection of two microRNAs with a visual ‘+’ or ‘-’ readout by AFM (124) (Figure 4C). The computational module could be designed as a ‘YES’ gate (i.e. standard single detection) or with an ‘AND’ gate activated by two microRNAs. In each case, the correct microRNA(s) lead to the release of a biotinylated ssDNA that recruits streptavidin to capture probes which are imaged by AFM.

Figure 4.

DNA origami microRNA biosensors. (A) DNA-PAINT detection strategy using super-resolution microscopy (122). (B) Removal of surface features on an origami tile for microRNA detection (123). (C) A logic-gated origami design for microRNA detection (124). (D) Reconfigurable origami pliers (125). (E) DNA origami device with gold nanorods that provide an optical signal (126). (F) A DNA box that opens on binding a microRNA (127).

Another general strategy for DNA origami sensing is the design of nanostructures that can reconfigure in response to microRNA. Komiyama and co-workers designed DNA origami pliers consisting of two levers with a central hinge, designed to open in the presence of a target microRNA (Figure 4D) (125). Partly complementary single-stranded extensions on both levers hold the pliers closed until a target microRNA binds and displaces one strand through toehold-mediated strand displacement, opening the pliers. The different conformations are observed using AFM imaging. Liedl and co-workers used a similar cross-type nanostructure but designed it to change bulk optical properties so that detection does not rely on AFM imaging (126). They developed a dynamic DNA origami nanostructure with a configuration-dependent plasmonic shift based on a target microRNA (Figure 4E). The two levers of the cross-shaped structure are connected by a single-stranded hinge, and contain complementary single-stranded extensions on each lever that are initially prevented from binding by a blocking oligo hybridized on one side. The target microRNA binds to a toehold region on this blocking oligo and removes it, resulting in the two levers locking in the closed configuration. Gold nanorods attached to both the levers cause the conformation switch to alter the plasmonic circular dichroism (CD) spectrum which is used as the detection readout. In another example, Kjems and colleagues developed a DNA origami box with a microRNA controllable lid (127) (Figure 4F). FRET dyes on the lid and box allowed the opening of the box to be detected with bulk fluorescence, and they further demonstrated a number of logic operations that could be implemented with microRNA to control lid opening.

Other DNA devices and assemblies

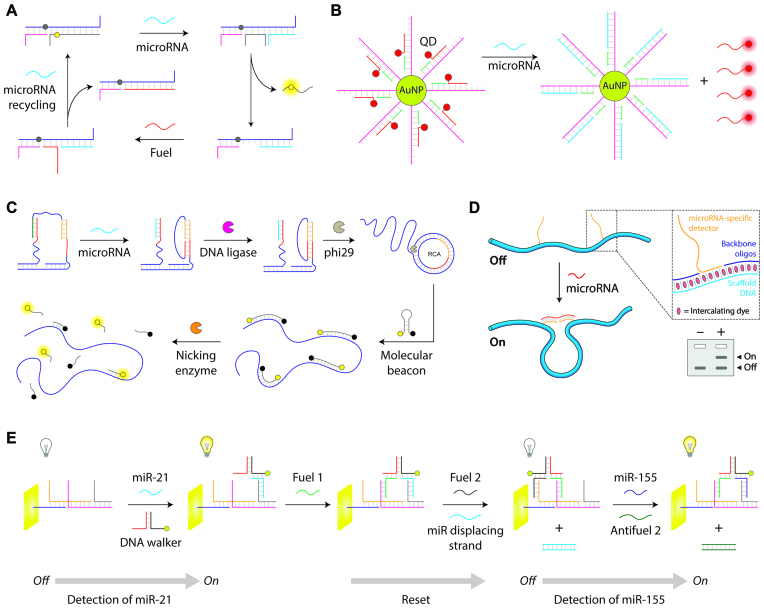

Our final category contains other types of DNA devices with approaches that include dynamic reconfigurations of DNA assemblies, cascading strand displacement DNA reactions, and nanoparticle-coupled approaches. The majority of these DNA devices rely on some kind of optical readout for detection, with most using bulk fluorescence.

In one example, Xiang and co-workers developed a DNA-based molecular machine that produces fluorescence in the presence of a target microRNA (128) (Figure 5A). They used a ssDNA scaffold with a quencher to hold a reporter strand with a fluorophore that is released by strand displacement upon binding a target microRNA. A fuel strand can be added to release the microRNA and enable ‘target recycling’ where it can cyclically trigger other DNA devices. Another fluorophore-quencher strategy by Ma and co-workers employed gold nanoparticles as the quenchers and quantum dots as the fluorophores (129) (Figure 5B). DNA anchors the QDs to the gold nanoparticles, and target microRNA triggers a strand displacement leading to the release of QDs and giving rise to fluorescence. The device is designed to recycle target microRNA to amplify the signal. Another strategy developed by Li and co-workers uses a microRNA to conditionally trigger amplification of a DNA fragment that is detected with a molecular beacon (130) (Figure 5C). The target microRNA triggers formation of a DNA loop, which is ligated to a closed circle and used as a template for rolling circle amplification (RCA). The amplification generates thousands of copies of the sequence which are detected by a molecular beacon that binds and is subsequently cleaved by a nicking enzyme, separating the fluorophore and the quencher to increase fluorescence.

Figure 5.

DNA devices for microRNA biosensing. (A) DNA strand displacement based device with a fluorescence readout (128). (B) Gold nanoparticle and quantum dot based quench-and-release strategy (129). (C) Strand displacement coupled with RCA-based signal amplification (130). (D) DNA nanoswitches with a gel-based readout (132). Reproduced from ref 132. (E) A DNA walker that can detect two microRNAs in forward and backward steps (134).

A few other DNA devices use distinct types of optical changes using gel electrophoresis or colorimetric changes. Our lab has developed DNA nanoswitches (131) that respond to specific microRNAs and undergo a conformational change that can be detected by gel electrophoresis (132) (Figure 5D). Single stranded extensions that are partly complementary to the target microRNA are positioned along the length of the DNA nanoswitch, causing target microRNA binding to induce a loop in the structure. This strategy can be used to quantify microRNAs from cellular extracts and can multiplex up to five different microRNAs by programming different loop sizes. Xiang and co-workers developed a colorimetric strategy based on cascaded self-assembly of DNA hairpins triggered by microRNA initiators (133). They used hairpins enclosing a G-quadruplex forming sequence that are opened in the presence of a microRNA and are assembled into a ferris-wheel-like structure. In this structure, the open hairpin sequences form G-quadruplexes that bind to hemin and act as DNAzymes to catalyze the conversion of the colorless TMB substrate into a yellow colored product.

Several DNA devices have been used for electrochemical sensing of microRNA. In one example, Yuan and co-workers designed an electrochemical sensor with a DNA walker that is activated in the presence of target microRNA (134) (Figure 5E). Target microRNA binds to a DNA track on the electrode and recruits an AuNP-containing DNA walker. Through a series of DNA inputs, the DNA walker can be made to move closer or away from the electrode surface, thereby turning the electrochemiluminescence from off to on. The same group designed an electro-chemiluminescence (ECL) sensor which contains hairpin probes with AuNPs closer to the surface of the electrode, thus quenching the fluorescence of the gold nanoparticles (135). Target microRNA causes the production of intermediate DNA pieces in a separate process. This intermediate DNA can unloop the hairpin and move the AuNPs away from the electrode surface, thus restoring fluorescence.

CRITICAL ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION

Features and challenges of DNA nanotechnology-based microRNA detection

Having surveyed DNA nanotechnology approaches for microRNA detection (describing ‘who’, ‘what’, ‘when’, ‘where’ and ‘how’), here we attempt to shed light on the big question—‘why’. What advantages does DNA nanotechnology offer for microRNA biosensing? We will touch on a few main advantages: Improving existing approaches, new approaches with reconfigurable structures, inherent biocompatibility, and enabling complex functionalities in biosensing. We will also discuss some challenges in this approach that include nanostructure formation, assay complexity, and stability of nanostructures.

Several features of DNA nanostructures have shown utility in microRNA detection. In surface-based assays, a critical challenge lies in controlling the structure, orientation, and density of DNA probes at the biosensing interface, which play important roles in efficiency and kinetics of target capture (103,104). In this context, DNA tetrahedra allow control over spatial density and orientation of DNA probes, maximizing target accessibility and minimizing non-specific adsorption and lateral interactions between probes (102). These concepts may also translate to other surface-based approaches such as ELISA and SPR (104,142). The programmability of DNA also opens up some entirely new sensing possibilities based on reconfiguration of DNA objects in response to a target sequence. A few examples in DNA origami and almost all in DNA devices and assemblies sections take advantage of the programmability of DNA to offer interesting new sensing approaches that help convey the many possibilities of DNA nanostructures for sensing. Using DNA nanostructures in microRNA sensing opens up the possibility of engineered biological sensors with inherent biocompatibility, and also offers the longer-term possibility of integrating such sensors with living biological systems. Some examples of this are already starting to emerge, where DNA nanotechnology is being used in living biological systems (22,143–145). Additionally, the programmable nature of DNA nanostructures enables unique and complex functionality. There are several such examples in this review including multiplexing (132), logic operations (124), and cascading events (106). DNA nanotechnology provides a way to build complexity into biosensors as needed, and the wide variety of ‘natural’ DNA interactions such as aptamer-ligand recognition (146), triplexes (147), i-motifs (148) and G-quadruplexes (149) also help facilitate the potential versatility of such biosensors.

Relating back to Table 2, we draw attention to a few common features in the surveyed DNA nanotechnology approaches that address common disadvantages of current approaches. For most of the surveyed approaches, a key advantage is that the microRNA does not need to be amplified, in contrast to some popular current approaches such as qPCR and next-generation sequencing. Relatedly, amplification (typically exponential) can pose a challenge for absolute (and even relative) quantification. Some of the DNA nanotechnology approaches discussed in this survey demonstrate direct detection of microRNA, thus eliminating any amplification-based errors. Many of the techniques have also demonstrated multiplexing, which is typically absent from qPCR and Northern blotting. Several also offer advantages in lowering cost or complexity compared to existing methods, sometimes enabling detection with little or no equipment, or with minimal training.

Despite these advantages, some challenges still remain in these approaches. The primary one among these may be formation of the nanostructures themselves, which typically requires thermal annealing of multiple components. While it can be straightforward, some structures and devices can require multiple steps, precise molar ratios, or long times that stretch over days. After structure formation, purification can sometimes be necessary to remove excess reagents or malformed structures. In part due to the construction issue, some biosensing assays using DNA nanostructures are complex, requiring many different steps in assay preparation and execution. A few even appear to be unnecessarily complex, sometimes resembling a Rube Goldberg apparatus. These sensing assays also need to be integrated into workflows that can be performed by end users, necessarily moving away from AFM imaging that is common for verifying structures. One last challenge in using DNA nanostructures for microRNA detection is the stability of the structures themselves. Since they are formed by base pairing of DNA, thermal stability and susceptibility to nucleases can both pose problems for certain applications. These challenges are solvable, and many of these aspects are currently being addressed by this relatively new field (150–152).

Needs and wants in microRNA detection

Sensitivity and specificity tend to be the most widely reported metrics for microRNA detection. For sensitivity, needs vary by application but some realistic limits can be defined for cellular extracts and biological fluids. For cellular extracts, 1 copy of microRNA/cell likely defines the lowest relevant amount, with typical ranges of 10–10,000 copies/cell (153). For total RNA extracts from cells, a 500 ng sample (∼25 000 cells) requires a detection limit of ∼0.04 amol to detect 1 copy per cell, and 0.4–400 amol to detect in the typical range. This corresponds to sub-pM to sub-nM range concentrations assuming microliter volumes. In biological fluids, microRNAs are diluted in milliliter to liter-scale volumes, resulting in lower concentrations. Published clinical results of microRNAs in body fluids tend to be primarily in the fM range (153–157), with some samples reportedly as low as 20 aM and as high as 20 nM (153). It is useful to note, however, that microRNAs need not be detected at their native concentrations; body fluids typically collected at the milliliter scale can be concentrated to the microliter scales typical for biosensing assays. Given these considerations, sensitivity is important but only to a degree; extreme sub-fM sensitivity may not be meaningful for microRNA detection. This assertion is further supported by the continued use of Northern blotting in microRNA detection, which has the lowest sensitivity of the common approaches (typically pM-nM) (158).

Specificity is important in microRNA detection since many microRNAs have similar sequences but different functions. Cross-talk between microRNAs can be problematic, and due to the relative rarity of individual microRNAs in biological samples, cross talk from other RNAs can increase the background signal and reduce sensitivity. While the ultimate specificity is to detect single-nucleotide variations, many applications may not require this level of specificity (e.g. microRNAs with no closely related sequences in the genome). It is also worth pointing out that specificity is likely to be a solvable problem for most assays. Since they all rely on nucleic acid hybridization, improved sequence design on one system should be ‘transferable’ to other systems as well. A large amount of work has been done on ‘tuning’ nucleic acid specificity (159,160), and toehold-based approaches offer increased flexibility in this area (161). Nucleic acid analogs such as peptide nucleic acid (PNA) and locked nucleic acid (LNA) with different base pairing affinities can also be added to tune or improve specificity (162,163). Thus, we contend that specificity differences between many assays are largely due to probe design and experimental conditions and not necessarily inherent to the different approaches.

Aside from sensitivity and specificity, there are several other aspects of sensing that are important for practical use that include cost, time, and complexity. These features can be underappreciated, which makes them both underreported in the literature and difficult to compare between different assays. Still, these features are important and can be critical for establishing an assay with a wide user base. Many assays that have been successful in reaching a wide user base build or improve on existing assays in a way that minimally disrupt existing workflows (164–166). This suggests that new assays should consider workflow and the likelihood of end users to have the resources and the skills to perform the assay. For clinical use, there can be a compromise on parameters such as sensitivity for rapid detection of biomarkers. For tools that are primarily developed for lab-based research, faster detection times are not as important, but eliminating the need for expensive equipment and creating easy-to-use methodologies are important especially in low resource settings. There has also been a recent push for ‘frugal science’, where cost is considered alongside the more typical performance metrics. This movement has produced interesting scientific tools such as centrifuges (167), microscopes (168), and water filtrations systems (169) with ultralow cost. As some examples in this review have shown, DNA nanotechnology approaches can integrate into existing workflows and due to low cost synthesis can be very cost-effective.

Critical comparison of approaches

The methods described in this article span the range from proof-of-concept explorations to more mature technologies with a history of progressive improvement. The authors appreciate the importance of experimentation with different methods for detecting microRNA, but it is not immediately obvious which of these techniques may become widely adopted for their intended purpose. In this section we discuss the relative merits of the different approaches, and provide some speculation on methods that may become more widespread. Most methods described in this article fall within the useful range of sensitivity and specificity for lab-based use, and some meet higher standards that might be needed for clinical use. As we mentioned earlier, improved sensitivity and specificity are attractive features, but we suspect that other features such as ease-of-use, cost, and equipment requirements may play a larger role in facilitating adoption.

So, where do these approaches sit among the landscape of existing tools? The niche of genome-wide screening of microRNAs is well established by next generation sequencing technologies and microarray. To our view, none of the methods in this report are poised to be competitive in this area; to our knowledge none have described a strategy for scaling up to the genome scale with thousands of microRNAs. Instead, the methods described here focus on the area of targeted detection and quantification of microRNAs, occupying a niche with the more dominant technologies of qPCR and Northern blotting. These two established methods arguably occupy their own niches, with qPCR based on amplification and being relatively expensive and Northern blotting offering direct detection and being relatively inexpensive but cumbersome. qPCR is often considered the gold standard of microRNA, and yet Northern blotting still remains common (158). Each of these have their own features and limitations as mentioned in the section on current microRNA detection methods above, so new methods shown here may occupy the same niche or carve out a new one. Moreover, these DNA nanotechnology-based approaches have compared their performances to traditional methods (mostly qPCR) but a comparative analysis of DNA nanostructure-based assays is lacking. Such analyses will be important in improving and adapting the techniques mentioned in this article, especially since the outcome of the assay can also be dependent on the methodology used even in traditional methods (170,171).

The electrochemical approaches have largely demonstrated improved detection using DNA nanostructures to control the surface interface. This is a great benefit of the nanoscale control that comes with DNA nanostructures, though there is some counter-evidence showing that similar results can be obtained with chemical monolayers (172). Overall, however, these DNA nanostructured electrochemical systems (which were predominantly tetrahedra in the literature) have impressively high sensitivity and specificity and have some potential for further adoption. The main drawbacks we see are the multiple steps (including several washes) in the assay as well as the relatively costly electrochemical workstations that are used. However, recent work shows that electronics can be simplified, potentially enabling this type of approach to be used as a general lab or point-of-care approach (173). It is worth noting here that although the electrochemical approaches used tetrahedra, it is possible that other shapes (including DNA origami structures) may provide similar results but were not reported in our literature search.

The microscopy-based approaches provide interesting demonstrations of how DNA nanotechnology can be ‘programmed’ and analyzed, but we contend that they are unlikely to be adopted for standalone detection purposes. Obtaining and analyzing high-resolution images by fluorescence microscopy or AFM is costly in time and money. Furthermore, the resulting detection metrics from these techniques is not compelling enough to justify the effort. Technologies such as DNA-PAINT have found success in the context of adding new features to imaging techniques that are used in biology (174,175) but when such imaging is a prerequisite for detecting microRNA or another analyte it becomes less useful. There are, however, some applications where imaging is an important aspect of detection. For example, some of these methods could be adapted for use when it is important to know the spatial distribution of RNAs within a biological sample such as a cell or a tissue. For many such applications in biology, imaging (especially fluorescence imaging) may already be part of the workflow and could potentially benefit from some of these DNA nanotechnology approaches.

The approaches that rely on optical changes may be the most likely in general to become widespread, due in part to the existing infrastructure in the life sciences and medicine to measure such changes. Fluorescent plate readers and gel assays are incredibly common in biology, so techniques that take advantage of these workflows have the lowest barrier to overcome in translating the technology. Our own technique of DNA nanoswitches (132,176,177) falls into this category, with one of the most compelling features being integration with existing workflows. Other examples that look promising in this category are fluorescence-based approaches such as those involving DNA-nanoparticle complexes (129), and the CD-based detection of the DNA origami cross (126). Some of these techniques could also benefit from handheld or portable readers, of which there are several examples being developed in the literature (178).

In looking at potential widespread adoption of particular technologies, another aspect to consider is evidence of sustained growth of a strategy or its demonstrated use for multiple applications. There are a few clear examples of this including use of the DNA tetrahedron to improve electrochemical sensing techniques (86,179) and the DNA nanoswitches from our lab (132,176,180). These techniques have also extended beyond microRNA detection and are used in detection of small molecules and proteins. There are also a few examples where the opposite seems to be true, and individual labs have demonstrated several different approaches that are largely unrelated (113,128,133,181). This might illustrate more exploratory developments where leading candidates for further development have not yet emerged.

A few methods have interesting features that could be especially useful for certain applications. One example is colorimetric detection, where the presence of certain microRNAs can be detected by eye (133). This could be a useful way to quickly and efficiently validate biological samples, and could prove useful for point-of-care detection if the sensitivity can be improved or if it can find application where disease-related microRNAs are abundant. Another example is live cell microRNA detection (113,114,129), which could provide new biological insights about microRNA activity inside living systems. Several of the methods also utilize the programmable nature of DNA to incorporate features such as multiplexed detection (107,122,132) or logic operations (124), which are all steps toward microRNA biosensors with more complex functionality. With many of these strategies testing efficiency in biofluids such as serum and urine, the potential of DNA nanostructures for diagnosis and disease monitoring does not seem not far off.

Some readers may be interested to know about the commercial potential for the technologies described above. While DNA nanotechnology-based microRNA techniques have not yet been commercialized to our knowledge, the DNA nanotechnology field has progressed in the last decade to spin out related companies. Most related to biosensing is a start-up company called Esya which uses a DNA device to scan cells for lysosomal disorders. The DNA nanoswitch from our group was briefly adopted by a (now defunct) start-up Confer Health for use in home-based fertility diagnostics. DNA-PAINT based company Ultivue provides immune-profiling and imaging reagents for super-resolution microscopy. This feature also allows monitoring RNA profiles in cells for their spatial distribution. Recently, the tools to create DNA origami structures were also commercialized by Tilibit Nanosystems which provides custom-made DNA scaffold and staple strands depending on customer requirements. This emerging commercial landscape suggests that these DNA nanotechnology approaches are starting to gain traction for certain applications.

CONCLUSION AND OUTLOOK

Nucleic acids are the natural biological sensors for microRNA, and in fact all of the major established methods for microRNA detection rely on nucleic acid probes hybridizing to all or part of their target microRNA. Given recent advances in structural DNA nanotechnology that enable precise building and reconfiguration, it is not a huge conceptual leap to suggest that DNA-based biosensors may be combined with molecular devices to impart complex functions that were once purely science fiction. These aspirational goals would include sense-respond devices or sense-compute-respond devices. Even setting these grand notions aside, we have shown here that there already exists a suite of tools enabled by DNA nanotechnology that offer some important advantages for microRNA detection. Furthermore, microRNA is a fitting molecule to ‘test the waters’ of DNA nanotechnology based biosensing, and we suspect it may be the tip of the iceberg as many of these approaches and others branch out to other applications. In particular, it may be relatively straightforward to adapt many of these technologies to detect other RNAs including mRNA, viral RNA, and long non-coding RNA. While we are not clairvoyant enough (or brave enough) to predict specific winners and losers among microRNA detection technologies, we can reasonably speculate that DNA nanotechnology approaches will play a role in the future of microRNA detection. Already these approaches are increasing the diversity of tools for microRNA detection, as well as demonstrating the power of DNA nanotechnology when form follows function.

FUNDING

We acknowledge support from American Heart Association [award 17SDG33670339 to BKD] and National Institute of General Medical Sciences [award R35GM124720 to KH]. Funding for open access charge: American Heart Association [17SDG33670339]; National Institute of General Medical Sciences [R35GM124720]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the American Heart Association or the NIGMS.

Conflict of interest statement. K.H. and A.R.C. are inventors on patents (issued and pending) on the DNA nanoswitches.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gu M., Zhang Q., Lamon S.. Nanomaterials for optical data storage. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016; 1:16070. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gong T., Xie J., Liao J., Zhang T., Lin S., Lin Y.. Nanomaterials and bone regeneration. Bone Res. 2015; 3:15029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Vikesland P.J. Nanosensors for water quality monitoring. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2018; 13:651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seeman N.C. DNA in a material world. Nature. 2003; 421:427–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Madsen M., Gothelf K.V.. Chemistries for DNA Nanotechnology. Chem. Rev. 2019; 110:6384–6458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hughes R.A., Ellington A.D.. Synthetic DNA synthesis and assembly: putting the synthetic in synthetic biology. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2017; 9:a023812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bustamante C., Bryant Z., Smith S.B.. Ten years of tension: single-molecule DNA mechanics. Nature. 2003; 421:423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Xavier P.L., Chandrasekaran A.R.. DNA-based construction at the nanoscale: emerging trends and applications. Nanotechnology. 2018; 29:062001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chandrasekaran A.R., Anderson N., Kizer M., Halvorsen K., Wang X.. Beyond the fold: emerging biological applications of DNA origami. ChemBioChem. 2016; 17:1081–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Seeman N.C., Kallenbach N.R.. Design of immobile nucleic acid junctions. Biophys. J. 1983; 44:201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. He Y., Ye T., Su M., Zhang C., Ribbe A.E., Jiang W., Mao C.. Hierarchical self-assembly of DNA into symmetric supramolecular polyhedra. Nature. 2008; 452:198–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Aldaye F.A., Sleiman H.F.. Modular access to structurally switchable 3D discrete DNA assemblies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007; 129:13376–13377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Winfree E., Liu F., Wenzler L.A., Seeman N.C.. Design and self-assembly of two-dimensional DNA crystals. Nature. 1998; 394:539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zheng J., Birktoft J.J., Chen Y., Wang T., Sha R., Constantinou P.E., Ginell S.L., Mao C., Seeman N.C.. From molecular to macroscopic via the rational design of a self-assembled 3D DNA crystal. Nature. 2009; 461:74–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chandrasekaran A.R. Programmable DNA scaffolds for spatially-ordered protein assembly. Nanoscale. 2016; 8:4436–4446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rothemund P.W.K. Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature. 2006; 440:297–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Douglas S.M., Dietz H., Liedl T., Högberg B., Graf F., Shih W.M.. Self-assembly of DNA into nanoscale three-dimensional shapes. Nature. 2009; 459:414–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Han D., Pal S., Nangreave J., Deng Z., Liu Y., Yan H.. DNA origami with complex curvatures in three-dimensional space. Science. 2011; 332:342–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wei B., Dai M., Yin P.. Complex shapes self-assembled from single-stranded DNA tiles. Nature. 2012; 485:623–626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ke Y., Ong L.L., Shih W.M., Yin P.. Three-dimensional structures self-assembled from DNA bricks. Science. 2012; 338:1177–1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Yurke B., Turberfield A.J., Mills A.P. Jr, Simmel F.C., Neumann J.L.. A DNA-fuelled molecular machine made of DNA. Nature. 2000; 406:605–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Narayanaswamy N., Chakraborty K., Saminathan A., Zeichner E., Leung K., Devany J., Krishnan Y.. A pH-correctable, DNA-based fluorescent reporter for organellar calcium. Nat. Methods. 2019; 16:95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Simmel F.C., Dittmer W.U.. DNA nanodevices. Small. 2005; 1:284–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Madhanagopal B.R., Zhang S., Demirel E., Wady H., Chandrasekaran A.R.. DNA nanocarriers: programmed to deliver. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2018; 43:997–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rajendran A., Endo M., Sugiyama H.. Single-molecule analysis using DNA origami. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012; 51:874–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ceze L., Nivala J., Strauss K.. Molecular digital data storage using DNA. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2019; doi:10.1038/s41576-019-0125-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Chakraborty K., Veetil A. T., Jaffrey S. R., Krishnan Y.. Nucleic acid–based nanodevices in biological imaging. Annu. Rev Biochem. 2016; 85:349–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chandrasekaran A.R., Wady H., Subramanian H.K.K.. Nucleic acid nanostructures for chemical and biological sensing. Small. 2016; 12:2689–2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Huang R., He N., Li Z.. Recent progresses in DNA nanostructure-based biosensors for detection of tumor markers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2018; 109:27–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xie N., Liu S., Yang X., He X., Huang J., Wang K.. DNA tetrahedron nanostructures for biological applications: biosensors and drug delivery. Analyst. 2017; 142:3322–3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang L., Arrabito G.. Hybrid, multiplexed, functional DNA nanotechnology for bioanalysis. Analyst. 2015; 140:5821–5848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ye D., Zuo X., Fan C.. DNA nanotechnology-enabled interfacial engineering for biosensor development. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2018; 11:171–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bartel D.P. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004; 116:281–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee R.C., Feinbaum R.L., Ambros V.. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993; 75:843–854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Friedman R.C., Farh K.K.-H., Burge C.B., Bartel D.P.. Most mammalian mRNAs are conserved targets of microRNAs. Genome Res. 2009; 19:92–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Weber J.A., Baxter D.H., Zhang S., Huang D.Y., Huang K.H., Lee M.J., Galas D.J., Wang K.. The microRNA spectrum in 12 body fluids. Clin. Chem. 2010; 56:1733–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang L., Chen X., Su T., Li H., Huang Q., Wu D., Yang C., Han Z.. Circulating miR-499 are novel and sensitive biomarker of acute myocardial infarction. J. Thorac. Dis. 2015; 7:303–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yang H., Gu J., Wang K.K., Zhang W., Xing J., Chen Z., Ajani J.A., Wu X.. MicroRNA expression signatures in barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009; 15:5744–5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kim Y.-W., Kim E.Y., Jeon D., Liu J.-L., Kim H.S., Choi J.W., Ahn W.S.. Differential microRNA expression signatures and cell type-specific association with Taxol resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2014; 8:293–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hébert S.S., Horré K., Nicolaï L., Papadopoulou A.S., Mandemakers W., Silahtaroglu A.N., Kauppinen S., Delacourte A., Strooper B.D.. Loss of microRNA cluster miR-29a/b-1 in sporadic Alzheimer's disease correlates with increased BACE1/β-secretase expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008; 105:6415–6420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Esteller M. Non-coding RNAs in human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2011; 12:861–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Calin G.A., Liu C.-G., Sevignani C., Ferracin M., Felli N., Dumitru C.D., Shimizu M., Cimmino A., Zupo S., Dono M. et al.. MicroRNA profiling reveals distinct signatures in B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemias. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004; 101:11755–11760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Qi J., Wang J., Katayama H., Sen S., Liu S.M.. Circulating microRNAs (cmiRNAs) as novel potential biomarkers for hepatocellular carcinoma. Neoplasma. 2012; 60:135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Iorio M.V., Visone R., Leva G.D., Donati V., Petrocca F., Casalini P., Taccioli C., Volinia S., Liu C.-G., Alder H. et al.. MicroRNA signatures in human ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2007; 67:8699–8707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Słotwiński R., Lech G., Słotwińska S.M.. MicroRNAs in pancreatic cancer diagnosis and therapy. Cent. Eur. J. Immunol. 2018; 43:314–324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Aghdam S.G., Ebrazeh M., Hemmatzadeh M., Seyfizadeh N., Shabgah A.G., Azizi G., Ebrahimi N., Babaie F., Mohammadi H.. The role of microRNAs in prostate cancer migration, invasion, and metastasis. J. Cell Physiol. 2019; 234:9927–9942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Li Z., Yu X., Shen J., Liu Y., Chan M.T.V., Wu W.K.K.. MicroRNA dysregulation in rhabdomyosarcoma: a new player enters the game. Cell Prolif. 2015; 48:511–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Iorio M.V., Ferracin M., Liu C.-G., Veronese A., Spizzo R., Sabbioni S., Magri E., Pedriali M., Fabbri M., Campiglio M. et al.. MicroRNA gene expression deregulation in human breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005; 65:7065–7070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cao X., Yeo G., Muotri A.R., Kuwabara T., Gage F.H.. Noncoding rnas in the mammalian central nervous system. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2006; 29:77–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sim S.-E., Lim C.-S., Kim J.-I., Seo D., Chun H., Yu N.-K., Lee J., Kang S.J., Ko H.-G., Choi J.-H. et al.. The brain-enriched microRNA miR-9-3p regulates synaptic plasticity and memory. J. Neurosci. 2016; 36:8641–8652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kim J., Inoue K., Ishii J., Vanti W.B., Voronov S.V., Murchison E., Hannon G., Abeliovich A.. A microRNA feedback circuit in midbrain dopamine neurons. Science. 2007; 317:1220–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Perkins D.O., Jeffries C.D., Jarskog L.F., Thomson J.M., Woods K., Newman M.A., Parker J.S., Jin J., Hammond S.M.. MicroRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Genome Biol. 2007; 8:R27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ling S.-C., Albuquerque C.P., Han J.S., Lagier-Tourenne C., Tokunaga S., Zhou H., Cleveland D.W.. ALS-associated mutations in TDP-43 increase its stability and promote TDP-43 complexes with FUS/TLS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010; 107:13318–13323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Edbauer D., Neilson J.R., Foster K.A., Wang C.-F., Seeburg D.P., Batterton M.N., Tada T., Dolan B.M., Sharp P.A., Sheng M.. Regulation of synaptic structure and function by FMRP-associated microRNAs miR-125b and miR-132. Neuron. 2010; 65:373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Liu N., Olson E.N.. MicroRNA regulatory networks in cardiovascular development. Dev. Cell. 2010; 18:510–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chen J.-F., Murchison E.P., Tang R., Callis T.E., Tatsuguchi M., Deng Z., Rojas M., Hammond S.M., Schneider M.D., Selzman C.H. et al.. Targeted deletion of Dicer in the heart leads to dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008; 105:2111–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhao Y., Ransom J.F., Li A., Vedantham V., Drehle M. von, Muth A.N., Tsuchihashi T., McManus M.T., Schwartz R.J., Srivastava D.. Dysregulation of cardiogenesis, cardiac conduction, and cell cycle in mice lacking miRNA-1-2. Cell. 2007; 129:303–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Small E.M., Frost R.J., Olson E.N.. MicroRNAs add a new dimension to cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2010; 121:1022–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Trobaugh D.W., Klimstra W.B.. MicroRNA regulation of RNA virus replication and pathogenesis. Trends Mol. Med. 2017; 23:80–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jopling C.L., Yi M., Lancaster A.M., Lemon S.M., Sarnow P.. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific MicroRNA. Science. 2005; 309:1577–1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Correia C.N., Nalpas N.C., McLoughlin K.E., Browne J.A., Gordon S.V., MacHugh D.E., Shaughnessy R.G.. Circulating microRNAs as potential biomarkers of infectious disease. Front. Immunol. 2017; 8:118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Girardi E., López P., Pfeffer S.. On the importance of host MicroRNAs during viral infection. Front. Genet. 2018; 9:439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Calin G.A., Croce C.M.. MicroRNA signatures in human cancers. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2006; 6:857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kumarswamy R., Volkmann I., Thum T.. Regulation and function of miRNA-21 in health and disease. RNA Biol. 2011; 8:706–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Meyer S.U., Pfaffl M.W., Ulbrich S.E.. Normalization strategies for microRNA profiling experiments: a ‘normal’ way to a hidden layer of complexity. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010; 32:1777–1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Witwer K.W. Circulating MicroRNA biomarker studies: pitfalls and potential solutions. Clin. Chem. 2015; 61:56–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Calin G.A., Sevignani C., Dumitru C.D., Hyslop T., Noch E., Yendamuri S., Shimizu M., Rattan S., Bullrich F., Negrini M. et al.. Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004; 101:2999–3004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chen Z., Xu L., Ye X., Shen S., Li Z., Niu X., Lu S.. Polymorphisms of microRNA sequences or binding sites and lung cancer: a meta-analysis and systematic review. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e61008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Qi J.-H., Wang J., Chen J., Shen F., Huang J.-T., Sen S., Zhou X., Liu S.-M.. High-resolution melting analysis reveals genetic polymorphisms in MicroRNAs confer hepatocellular carcinoma risk in Chinese patients. BMC Cancer. 2014; 14:643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Volinia S., Calin G.A., Liu C.-G., Ambs S., Cimmino A., Petrocca F., Visone R., Iorio M., Roldo C., Ferracin M. et al.. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006; 103:2257–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Sayed D., Abdellatif M.. MicroRNAs in development and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2011; 91:827–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhang Y., Lu Y., Yang B.. [Potential role of microRNAs in human diseases and the exploration on design of small molecule agents]. Yao Xue Xue Bao. 2007; 42:1115–1121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kloosterman W.P., Plasterk R.H.A.. The diverse functions of MicroRNAs in animal development and disease. Dev. Cell. 2006; 11:441–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Verma M., Asakura Y., Asakura A.. Inhibition of microRNA-92a increases blood vessels and satellite cells in skeletal muscle but does not improve duchenne muscular dystrophy–related phenotype in mdx mice. Muscle Nerve. 2019; 59:594–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Wu R., Li H., Zhai L., Zou X., Meng J., Zhong R., Li C., Wang H., Zhang Y., Zhu D.. MicroRNA-431 accelerates muscle regeneration and ameliorates muscular dystrophy by targeting Pax7 in mice. Nat. Commun. 2015; 6:7713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Liu N., Williams A.H., Maxeiner J.M., Bezprozvannaya S., Shelton J.M., Richardson J.A., Bassel-Duby R., Olson E.N.. microRNA-206 promotes skeletal muscle regeneration and delays progression of Duchenne muscular dystrophy in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2012; 122:2054–2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sylvius N., Bonne G., Straatman K., Reddy T., Gant T.W., Shackleton S.. MicroRNA expression profiling in patients with lamin A/C-associated muscular dystrophy. FASEB J. 2011; 25:3966–3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Assmann T.S., Recamonde-Mendoza M., Puñales M., Tschiedel B., Canani L.H., Crispim D.. MicroRNA expression profile in plasma from type 1 diabetic patients: Case-control study and bioinformatic analysis. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2018; 141:35–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Cai W., Zhang J., Yang J., Fan Z., Liu X., Gao W., Zeng P., Xiong M., Ma C., Yang J.. MicroRNA-24 attenuates vascular remodeling in diabetic rats through PI3K/Akt signaling pathway. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2019; 29:621–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Chen Q., Qiu F., Zhou K., Matlock H.G., Takahashi Y., Rajala R.V.S., Yang Y., Moran E., Ma J.. Pathogenic role of microRNA-21 in diabetic retinopathy through downregulation of PPARα. Diabetes. 2017; 66:1671–1682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Chien H.-Y., Lee T.-P., Chen C.-Y., Chiu Y.-H., Lin Y.-C., Lee L.-S., Li W.-C.. Circulating microRNA as a diagnostic marker in populations with type 2 diabetes mellitus and diabetic complications. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2015; 78:204–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Fan B., Luk A.O.Y., Chan J.C.N., Ma R.C.W.. MicroRNA and diabetic complications: a clinical perspective. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2017; 29:1041–1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Long J., Wang Y., Wang W., Chang B.H.J., Danesh F.R.. MicroRNA-29c is a signature microrna under high glucose conditions that targets sprouty homolog 1, and its in vivo knockdown prevents progression of diabetic nephropathy. J. Biol. Chem. 2011; 286:11837–11848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Boxberger N., Hecker M., Zettl U.K.. Dysregulation of inflammasome priming and activation by MicroRNAs in human immune-mediated diseases. J. Immunol. 2019; 202:2177–2187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Dai R., Ahmed S.A.. MicroRNA, a new paradigm for understanding immunoregulation, inflammation, and autoimmune diseases. Transl. Res. 2011; 157:163–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Chen C., Ridzon D.A., Broomer A.J., Zhou Z., Lee D.H., Nguyen J.T., Barbisin M., Xu N.L., Mahuvakar V.R., Andersen M.R. et al.. Real-time quantification of microRNAs by stem–loop RT–PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005; 33:e179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Várallyay É., Burgyán J., Havelda Z.. MicroRNA detection by northern blotting using locked nucleic acid probes. Nat. Protoc. 2008; 3:190–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Kloosterman W.P., Wienholds E., Bruijn E. de, Kauppinen S., Plasterk R.H.A.. In situ detection of miRNAs in animal embryos using LNA-modified oligonucleotide probes. Nat. Methods. 2006; 3:27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Duan D., Zheng K., Shen Y., Cao R., Jiang L., Lu Z., Yan X., Li J.. Label-free high-throughput microRNA expression profiling from total RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:e154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Beckers M., Mohorianu I., Stocks M., Applegate C., Dalmay T., Moulton V.. Comprehensive processing of high-throughput small RNA sequencing data including quality checking, normalization, and differential expression analysis using the UEA sRNA Workbench. RNA. 2017; 23:823–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Zhou Y., Huang Q., Gao J., Lu J., Shen X., Fan C.A.. A dumbbell probe-mediated rolling circle amplification strategy for highly sensitive microRNA detection. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010; 38:e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Su X., Teh H.F., Lieu X., Gao Z.. Enzyme-based colorimetric detection of nucleic acids using peptide nucleic acid-immobilized microwell plates. Anal. Chem. 2007; 79:7192–7197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Chen J., Zhou X., Ma Y., Lin X., Dai Z., Zou X.. Asymmetric exponential amplification reaction on a toehold/biotin featured template: an ultrasensitive and specific strategy for isothermal microRNAs analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:e130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Kalantar-zadeh K., Fry B. eds. Introduction. Nanotechnology-Enabled Sensors. 2008; Boston: Springer; 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 95. Degliangeli F., Pompa P.P., Fiammengo R.. Nanotechnology-based strategies for the detection and quantification of MicroRNA. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014; 20:9476–9492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Ko H.Y., Lee J., Joo J.Y., Lee Y.S., Heo H., Ko J.J., Kim S.. A color-tunable molecular beacon to sense miRNA-9 expression during neurogenesis. Sci. Rep. 2014; 4:4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Wang B., You Z., Ren D.. Target-assisted FRET signal amplification for ultrasensitive detection of microRNA. Analyst. 2019; 144:2304–2311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Alhasan A.H., Kim D.Y., Daniel W.L., Watson E., Meeks J.J., Thaxton C.S., Mirkin C.A.. Scanometric MicroRNA array profiling of prostate cancer markers using spherical nucleic acid–gold nanoparticle conjugates. Anal. Chem. 2012; 84:4153–4160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Choi C.K.K., Li J., Wei K., Xu Y.J., Ho L.W.C., Zhu M., To K.K.W., Choi C.H.J., Bian L.. A gold@polydopamine core–shell nanoprobe for long-term intracellular detection of MicroRNAs in differentiating stem cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015; 137:7337–7346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Liu C., Chen C., Li S., Dong H., Dai W., Xu T., Liu Y., Yang F., Zhang X.. Target-triggered catalytic hairpin assembly-induced core–satellite nanostructures for high-sensitive “Off-to-On” sers detection of intracellular MicroRNA. Anal. Chem. 2018; 90:10591–10599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Goodman R.P., Schaap I. a. T., Tardin C.F., Erben C.M., Berry R.M., Schmidt C.F., Turberfield A.J.. Rapid chiral assembly of rigid DNA building blocks for molecular nanofabrication. Science. 2005; 310:1661–1665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Pei H., Lu N., Wen Y., Song S., Liu Y., Yan H., Fan C.. A DNA nanostructure-based biomolecular probe carrier platform for electrochemical biosensing. Adv. Mater. 2010; 22:4754–4758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Soleymani L., Fang Z., Sargent E.H., Kelley S.O.. Programming the detection limits of biosensors through controlled nanostructuring. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2009; 4:844–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]