Abstract

The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH) critically regulates carbohydrate metabolism. Phosphorylation of PDH by one of the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases 1–4 (PDK1–4) decreases the flux of carbohydrates into the TCA cycle. Inhibition of PDKs increases oxidative metabolism of carbohydrates, so targeting PDKs has emerged as an important therapeutic approach to manage various metabolic diseases. Therefore, it is highly desirable to begin to establish imaging tools for noninvasive measurements of PDH flux in rodent models. In this study, we used hyperpolarized (HP) 13C-magnetic resonance spectroscopy to study the impact of a PDK2/PDK4 double knockout (DKO) on pyruvate metabolism in perfused livers from lean and diet-induced obese (DIO) mice and validated the HP observations with high-resolution 13C-nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy of tissue extracts and steady-state isotopomer analyses. We observed that PDK-deficient livers produce more HP-bicarbonate from HP-[1-13C]pyruvate than age-matched control livers. A steady-state 13C-NMR isotopomer analysis of tissue extracts confirmed that flux rates through PDH, as well as pyruvate carboxylase and pyruvate cycling activities, are significantly higher in PDK-deficient livers. Immunoblotting experiments confirmed that HP-bicarbonate production from HP-[1-13C]pyruvate parallels decreased phosphorylation of the PDH E1α subunit (pE1α) in liver tissue. Our findings indicate that combining real-time hyperpolarized 13C NMR spectroscopy and 13C isotopomer analysis provides quantitative insights into intermediary metabolism in PDK-knockout mice. We propose that this method will be useful in assessing metabolic disease states and developing therapies to improve PDH flux.

Subject terms: Biochemistry, Physiology

Introduction

The pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) complex plays a central role in metabolic regulation1,2. PDH catalyzes the irreversible oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA and links glucose metabolism to the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle3,4. PDH is regulated by several factors including nutritional state and cellular energy demand as well as concentrations of pyruvate, acetyl-CoA, ATP, and NADH. The activity of PDH is also rapidly regulated by phosphorylation and dephosphorylation by pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK) and pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatases (PDP), respectively5–7. Prolonged feeding of a diet high in saturated fats increases PDK expression in rodent models8,9. Increased PDK expression in obesity contributes to lower PDH activity and reduced oxidation of carbohydrates10. This suggests that inhibition of PDK 2 and PDK 4 may reverse adverse metabolic effects by increasing pyruvate oxidation.

A number of studies have shown that targeting PDK activity is indeed promising for the treatment of obesity-related metabolic conditions11–14. Small molecules such as dichloroacetate inhibit PDKs and administration is associated with improved glucose tolerance in rodent models13–16. However, because dichloroacetate is carcinogenic and relatively nonspecific for PDK, alternative approaches for inhibition of PDK have been developed. For example, Tso et al. recently reported that targeting PDK with 2-[(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)sulfonyl] isoindoline-4,6-diol (designated PS10) resulted in improved glucose tolerance in mice16. Genetic knockouts of PDK isoforms have also been reported11,12,17. Consistent with results from pharmacological inhibition, Jeoung et al. found that knockout of both PDK 2 and 4 (double knockout, DKO) in mice resulted in increased PDH activity and lower blood glucose levels in both fed and fasted states12. In addition and somewhat unexpectedly, hepatic steatosis was improved in obese animals with either pharmacological inhibition of PDK 2/4 or knock out of PDK 2/4. Thus, monitoring the effects of PDK inhibition on pyruvate metabolism will be useful for understanding metabolic disorders and developing therapies targeting this system.

These earlier studies relied on invasive analysis of tissue extracts. Noninvasive hyperpolarization methods have been introduced to assess the alternative pathways of pyruvate metabolism in intact tissue with the prospect of human applications18,19. Metabolism of [1-13C]pyruvate through PDH yields [13C]bicarbonate20. Flux through PC may also yield [13C]bicarbonate through multiple reaction steps20–22. After administration of HP [1-13C]pyruvate, C1- and C4-labeled aspartate and malate appear as a consequence of flux through pyruvate carboxylase followed by scrambling in the symmetric fumarate and succinate pools21,23,24. Consequently, in principle HP [13C]bicarbonate may arise through decarboxylation via four enzymes: the malic enzyme, PEPCK, isocitrate dehydrogenase or alpha-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase. Rodent models of type 1 diabetes and obesity are associated with increased expression of pyruvate carboxylase which may indicate that a significant source of HP [13C]bicarbonate may reflect pyruvate carboxylation25. Sources of [13C]bicarbonate in the liver in models of obesity and the sensitivity to changes in PDK activity have not been evaluated, and results in the literature are conflicting. In a study of lean rats using hyperpolarization methods and validation with conventional 13C methods, HP [13C]bicarbonate production was detected in fed but not fasted animals22,26. In contrast, in a study of diet-induced obesity in the mouse, where PDH activity is thought to be reduced, even with 24 hours of fasting the appearance of [13C]bicarbonate was attributed to flux through PDH23. In isolated livers supplied with fatty acids which suppressed flux in PDH, much of the [13C]bicarbonate production was via PC and downstream pathways20,21.

It is important to understand the relative contributions of PDH and PC flux to bicarbonate production to assess interventions targeting PDKs in vivo using HP methods. The current study was designed to determine whether the appearance of [13C]bicarbonate after administration of [1-13C]pyruvate can be used as a reliable indicator of PDH flux in diet-induced obesity. Non-polarized 13C-enriched substrates were also present during the HP experiment, but these metabolites were undetectable on the time-scale of the HP exam. Coupled with measurements of hepatic oxygen consumption, flux through PDH versus PC could be calculated in livers from PDK2/PDK4 double knockout (DKO) mice exposed to a normal or high-fat diet. The correlation between the appearance of HP 13C-bicarbonate and the knockout of hepatic PDK enzymes is important for translating HP 13C-MRS as a noninvasive imaging tool for the treatment and management of chronic liver diseases.

Results

Real-time 13C magnetic resonance spectroscopy detects increased production of hyperpolarized bicarbonate in PDK-deficient livers

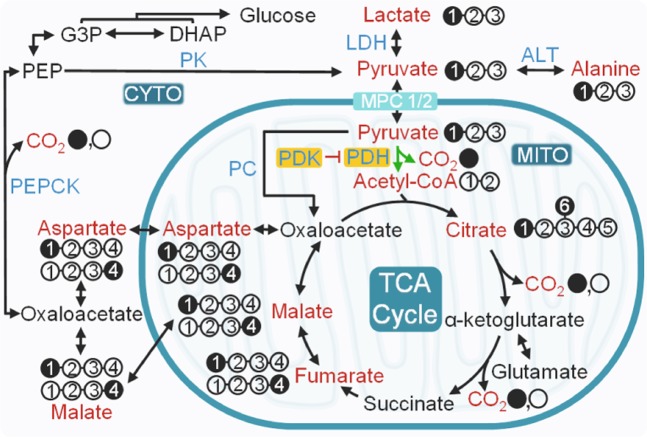

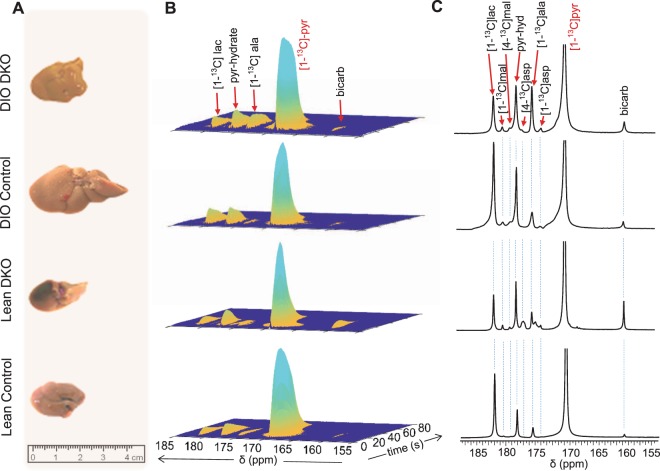

The potential pathways for metabolism of HP [1-13C]pyruvate in a liver are illustrated in Fig. 1. Livers isolated from the four groups of mice varied in size, with DIO control livers being significantly larger (Fig. 2A) than those from other groups reflective of fat accumulation11,16. The average weights of the isolated livers were 1.51 ± 0.28 g, 1.58 ± 0.46 g, 3.81 ± 0.44 g, and 2.10 ± 0.58 g for lean control, lean DKO, DIO control, and DIO DKO mice, respectively (Fig. S1A). During the HP 13C NMR examination, multiple metabolic products of pyruvate were detected in all groups of livers shortly after the injection of HP [1-13C]pyruvate (Fig. 2B). Representative summed 13C spectra (50 spectra collected over 100 s) are displayed in Fig. 2C. 13C resonances reflecting [1-13C]pyruvate, [13C]bicarbonate (160.9 ppm), [1-13C]aspartate (175.3), [1-13C]alanine (176.5 ppm), [4-13C]aspartate (178.3), [4-13C1]malate (180.3 ppm), [1-13C4]malate (181.5 ppm) and [1-13C]lactate (183.1 ppm) were all visible. These results are consistent with previous reports on the metabolism of HP [1-13C]pyruvate via both PC and PDH.

Figure 1.

Metabolic fates of HP [1-13C]pyruvate in an isolated perfused mouse liver. Filled circles represent 13C-enriched carbons while the open circles denote carbon atoms without 13C-enrichment. Metabolites labeled with HP 13C isotope from HP [1-13C]pyruvate, therefore potentially traceable by 13C NMR, are shown in red. All four-carbon intermediates are shown as two isotopomers with 13C-labelling at either the C1 or the C4 position. The intermediates with 13C-labelling at C1 are produced by direction carboxylation of HP [1-13C]pyruvate to [1-13C]oxaloacetate. Metabolism of the resulting [1-13C]oxaloacetate to [1-13C]malate followed by backward scrambling by fumarase results in the production of four-carbon intermediates with 13C-labelling at C4. ALT: alanine transaminase; CYTO: cytosol; G3P: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; MITO: mitochondria; MPC1/2: mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 and 2; PDH: pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; PDK: pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; PC: pyruvate carboxylase; PEP: phosphoenolpyruvate; PEPCK: phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and TCA: tricarboxylic acid.

Figure 2.

Time-resolved HP 13C MR of isolated perfused livers after giving HP [1-13C]pyruvate. (A) Representative photographs of the isolated livers from all four groups of mice used in this study; (B) time-resolved 13C NMR signals of perfused mouse livers after receiving HP [1-13C]pyruvate (2 mM); and (C) representative 13C NMR spectra of the perfused livers obtained by summing 50 free-induction decays acquired over 100 s. Compared to their respective controls, 13C bicarbonate was increased in the double knockouts, consistent with increased flux through pyruvate dehydrogenase.

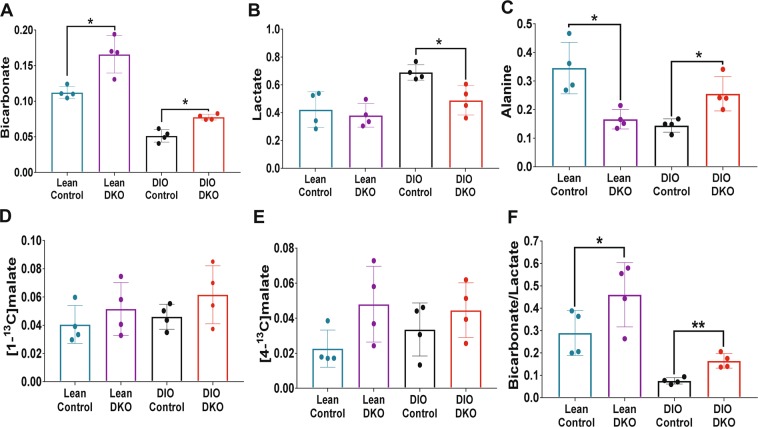

The resonances of lactate and alanine, dominant in all spectra, reflect rapid exchange with HP-pyruvate through single enzyme-catalyzed steps, lactate dehydrogenase, and alanine aminotransferase, respectively. A larger 13C-bicarbonate signal was observed in DKO livers from both lean and obese animals with the lean DKO livers producing the most 13C-bicarbonate (Fig. 2B,C). The average signal intensities of 13C-bicarbonate, [1-13C]lactate, and [1-13C]alanine normalized to the total signal of all HP 13C metabolites are shown in Fig. 3A–C, respectively. From these plots, it is clear that more HP 13C-bicarbonate was generated from HP-pyruvate in livers from lean DKO mice than those from the wild-type groups in both lean and obese animals (P < 0.05). It was also evident that less HP 13C-bicarbonate was produced in obese livers compared to the lean groups.

Figure 3.

The impact of PDK DKO on HP [1-13C]pyruvate metabolism. Normalized fractional intensities of (A) bicarbonate, (B) lactate, and (C) alanine; (D) [1-13C]malate, (E) [4-13C]malate, and (F) bicarbonate/lactate ratio; Data presented as the mean ± SD (n = 4 per group) with statistical significance of differences indicated by “*” (P < 0.05) and “**” (P < 0.001). DIO: diet-induced obese; and DKO: double knockout of PDK2/4.

The amount of HP [1-13C]lactate produced in these livers (Fig. 3B) showed the opposite trend. Here, more HP-[1-13C]lactate was observed in livers from DIO obese animals likely reflecting a more highly reduced tissue redox state. The amount of HP-lactate was lower in DIO DKO animals compare to DIO controls, perhaps reflecting greater flux of HP-pyruvate through PDH and less through LDH. This was less evident in the lean controls versus lean DKO comparisons. A somewhat different pattern was observed in the appearance of HP [1-13C]alanine (Fig. 3C). In the lean groups, less HP [1-13C]alanine was found in DKO livers compared to controls (P < 0.05) yet there was more HP-[1-13C]alanine detected in obese DIO DKO livers compared to DIO controls, the livers that accumulated the most fat (P < 0.05).

The signals of the 4-carbon TCA cycle intermediates, 13C-malate and 13C-aspartate, reflects carboxylation of HP [1-13C]pyruvate to form oxaloacetate. The NMR signals of [1-13C]malate and [4-13C]malate (Fig. 3D,E) tended to be more intense in DKO livers compared to controls but these differences did not reach statistical significance. Also, the intensity of the [1-13C]malate resonances tended to be higher than the intensity of the [4-13C]malate resonances. This reflects incomplete scrambling of [1-13C]oxaloacetate (formed directly by carboxylation of [1-13C]pyruvate) through fumarase to form equivalent amounts of [4-13C]oxaloacetate, [4-13C]aspartate, and [4-13C]malate.

Finally, the ratio of HP-bicarbonate to HP-lactate has previously been used as an overall index for the metabolism of HP [1-13C]pyruvate in vivo. These ratio comparisons are shown in Fig. 3F. This index was higher in both lean groups (control and DKO) than in both DIO groups (control and DKO). The index was significantly higher in both DKO groups compared to their respective controls. Moreover, a higher bicarbonate/lactate ratio was observed in DIO DKO livers compared to DIO control livers.

Alternative pathways of pyruvate metabolism and bicarbonate production from isotopomer analysis

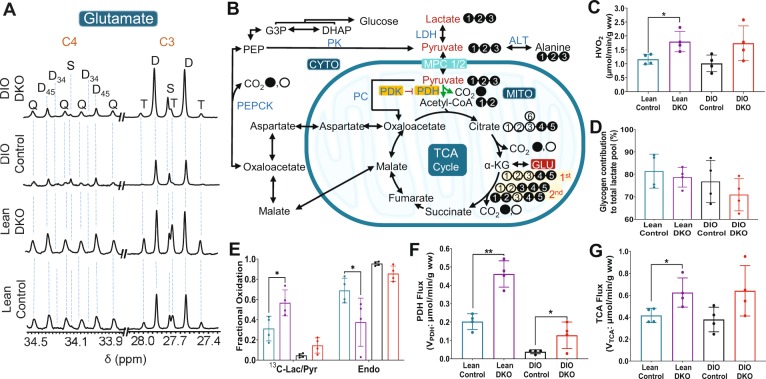

The temporal resolution for the appearance of [13C]bicarbonate after pyruvate administration was on the order of a few seconds (Fig. 2), but the metabolic pathways leading to bicarbonate production cannot be determined from hyperpolarization data. For this reason, the same livers were also perfused with medium containing 1.5 mM [U-13C]lactate and 0.15 mM [U-13C]pyruvate before and after the HP experiment, followed by tissue extraction and analysis that is independent of hyperpolarization results. Examples of the 13C NMR spectrum of glutamate C3 and C4 for each of the four groups of livers are compared in Fig. 4. Oxidation of [U-13C]pyruvate produces [1,2-13C2]acetyl-CoA, which enters the TCA cycle to produce [4,5-13C2]α-ketoglutarate. The 13C-labeled metabolic intermediate rapidly exchanges with glutamate, resulting in glutamate with 13C-labeling at C4 and C5 positions ([4,5-13C2]glutamate). This labeling pattern appears as a doublet (D45) in C4 multiplet. Further metabolism of [4,5-13C2]α-ketoglutarate through the TCA cycle produces [1,2-13C2]oxaloacetate or [3,4-13C2]oxaloacetate following hydration of fumarate (fumarase). Subsequently, these oxaloacetate condense with newly produced [1,2-13C2]acetyl-CoA, eventually producing [3,4,5-13C3]glutamate and [1,2,4,5-13C4]glutamate. The C4 carbon resonance of [3,4,5-13C3]glutamate appears as a doublet of doublets or quartet (Q). The larger doublet of doublets (or quartet) in glutamate C4 and the larger doublet of doublets (or triplet) in glutamate C3 were consistent with higher fractional 13C enrichment in acetyl-CoA in lean animals. The scheme in Fig. 4B explains the appearance of 13C-multiplets as a result of [U-13C]pyruvate metabolism.

Figure 4.

Metabolic parameters obtained by 13C NMR isotopomer analysis of tissue glutamate. (A) glutamate C-4 (34.20 ppm) and C-3 (27.60 ppm) resonances; (B) a metabolic scheme showing 13C-labeling of glutamate isotopomers; (C) oxygen consumption; (D) contribution of glycogen to the total lactate pool; (E) fractional oxidation of 13C-lactate/13C-pyruvate and endogenous sources for energy production by the TCA cycle; (F) pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) flux; and (G) tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA) flux. The letters S, D, T, and Q refer to a singlet, doublet (with the relevant J-coupled spins), triplet (a degenerate doublet of doublets), and quartet (or doublet of doublets), respectively. Filled circles in the metabolic scheme represent 13C-enriched carbons while open circles represent natural abundance levels of 13C. 13C-enriched pyruvate and lactate supplied in the perfusion medium are shown in red in (B). For viewing simplicity, only 13C-labeled glutamate isotopomers generated after the 1st and 2nd turns are shown. 13C-labeling patterns of other metabolites can be generated using tcaSIM and tcaCALC (downloadable free of charge at http://www.invivometabolism.org/tca.html. Abbreviations: α-KG = α-ketoglutarate; ALT = alanine transaminase; CYTO = cytosol; G3P = glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; GLU = glutamate; LDH = lactate dehydrogenase; MITO = mitochondria; MPC1/2 = mitochondrial pyruvate carrier 1 and 2; PDH = pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; PDK = pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; PC = pyruvate carboxylase; PEP = phosphoenolpyruvate; PEPCK = phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, TCA = tricarboxylic acid; and gww = gram wet weight. The bar plots represent the mean ± SD (n = 4 per group) with significance indicated by “*” (P < 0.05) and “**” (P < 0.001).

Hepatic oxygen consumption (Fig. 4C) was significantly higher in livers from lean DKO animals (1.79 ± 0.36 µmol/min/gww) compared to livers from lean controls (1.16 ± 0.18 µmol/min/gww). However, an increase in oxygen consumption was also observed in DIO DKO (1.73 ± 0.62 µmol/min/gww) compared to DIO controls (1.01 ± 0.29 µmol/min/gww), but these differences did not reach statistical significance. The DKO of PDK2/4 renders the liver metabolically more active but the subsequent effects of high-fat diet such as hepatic steatosis/fat accumulation in tissue and weight gain27 (Fig. S1B) were also observed in the DIO DKO livers. In all groups, unlabeled acetyl-CoA was detected in spite of providing only 13C labeled pyruvate and lactate in the medium. The unlabeled material must arise from either glycogen or endogenous triglycerides. A comparison of glycogen contribution to the total pyruvate and lactate pool in these livers is shown in Fig. 4D. A small decrease was observed in glycogen contribution from lean control (81.40 ± 7.59%) to DIO control (76.80 ± 9.34%) and from lean DKO (78.72 ± 4.42%) to DIO DKO (70.93 ± 7.17%). The fractional contribution of unlabeled sources is shown in Fig. 4E, demonstrating higher unlabeled contribution to acetyl-CoA in DIO animals.

PDH flux (VPDH, Fig. 4F) estimated from 13C isotopomer analysis of glutamate multiplets (see Fig. S2) was significantly higher in livers from lean DKO animals (0.46 ± 0.07 µmol/min/gww) and DIO DKO animals (0.12 ± 0.07 µmol/min/gww) than their respective controls (Lean control: 0.20 ± 0.04 µmol/min/gww and DIO Control: 0.03 ± 0.01 µmol/min/gww). A similar trend was also observed for TCA cycle flux (VTCA, Fig. 4G). The flux values for lean DKO, DIO DKO, lean control, and DIO control was 0.62 ± 0.13, 0.64 ± 0.23, 0.41 ± 0.06, and 0.37 ± 0.11 µmol/min/gww, respectively. Thus, liver metabolism with predominant fat oxidation (DIO controls) switches to a metabolic state in which increased carbohydrate contribution as an energy source is achieved (DIO DKO) by increasing both VPDH and VTCA.

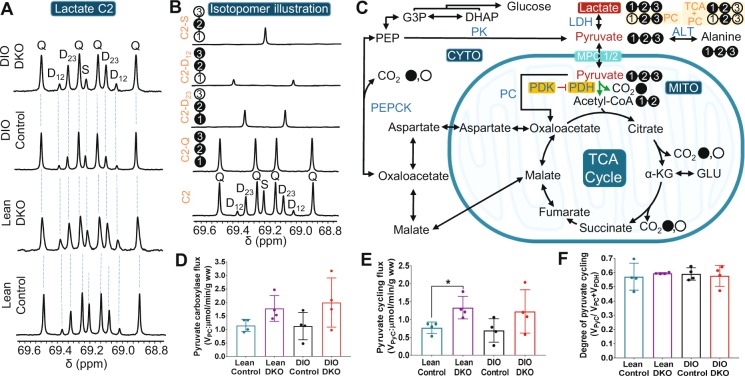

Pyruvate carboxylase flux (VPC), however, was not different among these groups. VPC for lean control, lean DKO, DIO control, and DIO DKO was 1.14 ± 0.23, 1.78 ± 0.47, 1.12 ± 0.50, and 1.99 ± 0.90 μmol/min/gww, respectively (Fig. 5D). The trend suggests that higher PC flux in DKO livers in both lean and DIO groups. However, the increase was small and the difference was not statistically significant. In summary, knockout of PDKs was associated with significantly increased PDH flux in both lean and DIO animals and no significant increase in PC flux. Together, these results suggest that the increased appearance of [13C]bicarbonate by HP is a useful biomarker of PDH flux in mouse models of obesity.

Figure 5.

Metabolic parameters obtained by 13C NMR isotopomer analyses of lactate and glutamate in tissue extracts. (A) multiplets in lactate C-2 (69.20 ppm); (B) simulated spectra showing singlet, doublet, and quartet and sum of multiplets in lactate C-2; (C) a scheme illustrating the production of all possible 13C-labeled lactate isotopomers; (D) pyruvate carboxylase (VPC) flux; (E) pyruvate cycling flux (VPK); and (F) degree of pyruvate cycling in each group of livers. The letters S, D, T, and Q refer to a singlet, doublet (with the relevant J-coupled spins), triplet (a degenerate doublet of doublets), and quartet (doublet of doublets), respectively. Filled and open circles in the metabolic scheme represent 13C-enriched and natural abundant 13C carbons in lactate, respectively. The remaining abbreviations are identical to those given in Fig. 4. The bar plots reflect the mean ± SD (n = 4 per group) with a statistical significance of differences indicated by “*” (P < 0.05).

Pyruvate cycling was observed in all perfused livers

In this study, the only 13C-labeled compounds were [U-13C]lactate and [U-13C]pyruvate. Pyruvate cycling was defined here as any pathway involving carboxylation of pyruvate followed by decarboxylation of another TCA cycle intermediate that ultimately regenerates pyruvate. Flux through the pathway pyruvate » oxaloacetate » malate » pyruvate (where malic enzyme is the key step) and flux through the pathway pyruvate » oxaloacetate » PEP » pyruvate (where pyruvate kinase is the key step) are both included. If pyruvate cycling is active, it can be detected in the 13C NMR spectrum of both lactate and glutamate.

The 13C NMR spectrum of lactate C2 is shown in Fig. 5A in all groups, a doublet due to J12 and a doublet due to J23 was observed in the 13C NMR spectrum. The doublets due to J12 and J23 in C2 of lactate (Fig. 5A) can only arise from flux of 4-carbon intermediates from the TCA cycle and back into pyruvate and lactate via pyruvate kinase (PK) or an equivalent pathway (Fig. 5B). There was no difference in the contribution of these doublets to the lactate signal among the four groups. As illustrated in Fig. 5B, the regeneration of pyruvate from the 13C-enriched 4-carbon intermediates results in pyruvate and lactate molecules with various 13C-labeling patterns. Metabolism of [U-13C]pyruvate through PC generates two different OAA isotopomers: [1,2,3-13C3]- and [2,3,4-13C3]OAA, and subsequent pyruvate cycling results in [2,3-13C2]lactate. While metabolism of [U-13C]pyruvate after the first TCA cycle turn followed by pyruvate cycling produces [1,2-13C2]lactate and [3-13C]lactate. [1-13C]lactate and [2-13C]lactate has produced from pyruvate cycling of 4-carbon intermediates generated after [U-13C]pyruvate has completed the second turn of the TCA cycle. Because the lactate 13C signal also includes lactate in the medium, further quantitative analysis was not performed.

The 13C NMR spectrum of glutamate is also sensitive to pyruvate cycling. Results for pyruvate carboxylation were described above and are shown in Fig. 5D. Pyruvate cycling flux (VPyC) correlates well with the changes in VPC (Fig. 5E). DKO livers have higher VPyC (1.33 ± 0.31 μmol/min/gww for lean DKO and 1.22 ± 0.60 μmol/min/gww for DIO DKO) while lower VPyC values were found for wild-type control livers (0.76 ± 0.16 μmol/min/gww for lean control and 0.69 ± 0.32 μmol/min/gww for DIO control). The degree of hepatic pyruvate cycling as estimated from VPyC/(VPC + VPDH)28,29 was 0.57 ± 0.09, 0.59 ± 0.01, 0.58 ± 0.04, and 0.57 ± 0.07 for lean control, lean DKO, DIO control, and DIO DKO, respectively (Fig. 5F). These results indicate that pyruvate cycling expressed as a fraction of TCA cycle flux is not sensitive to either DIO or DKO status. These results are consistent with the similarity of the 13C NMR spectra of lactate across the 4 groups (Fig. 5A).

PDK deficiency results in reduced fat accumulation

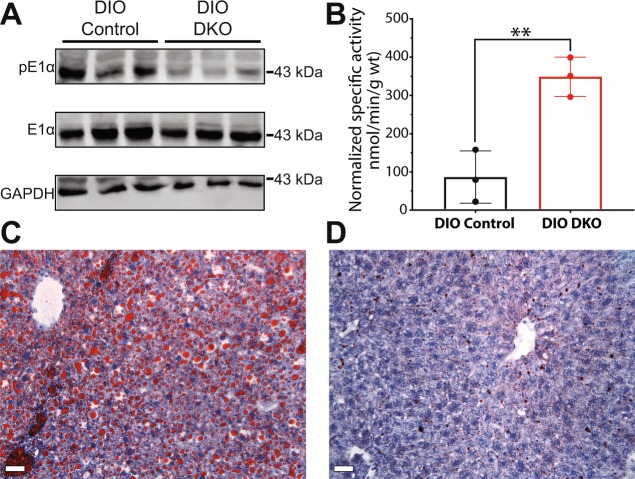

Phosphorylation of Ser293 on the E1α subunit of PDH by one of the PDKs results in inhibition of the activity of PDH. Western blot analyses of tissue samples (Fig. 6A) indeed showed that phosphorylation of the E1α subunit was very low in DIO DKO livers compared to DIO control livers. Furthermore, the activity of PDH measured in tissue homogenate samples showed that PDH activity was more than 3-fold higher in DIO DKO livers compared to DIO controls (Fig. 6B). The two-fold increase of PDH activity in liver (Fig. 6B) is similar to changes in the appearance of HP [13C]bicarbonate (Fig. 2B) in DIO DKO livers. DIO control livers (Fig. 6C) showed significant accumulation of fat while livers from the DKO mice showed minimal fat accumulation (Fig. 6D). To further validate the effect of PDK deficiency in livers, we analyzed glucose production in a representative set of lean control and lean DKO mice. 13C spectra of glucose converted to monoacetone glucose (MAG)30 indicated that the lean-DKO mice have profoundly lower gluconeogenesis compared to lean control (Fig. S3). These results support earlier reports that double knockout of PDK2/PDK4 restores hepatic metabolism of glucose in obese/pre-diabetic states.

Figure 6.

Western blots, specific activity, and histology. (A) Western blots showing phosphorylated PDH E1α subunit (pE1α), total phosphorylated PDH E1α subunit in tissue lysates from DIO control and DIO DKO livers (n = 3 livers). GAPDH serves as a loading control. The images were collected from three gels. Raw images of these three gels are shown in Supplementary Information (Fig. S5). (B) PDH specific activity; Representative Red Oil O stains from (C) DIO control and (D) DIO DKO livers. The red color in each image is attributed to stained lipids within the liver. The scale bars are 20 µm. The bar graph in (B) reflects the mean ± SD (n = 3 per group) with a statistical significance of differences indicated by “*” (P < 0.05) and “**” (P < 0.001).

Discussion

PDH kinases modulate the metabolic state of the liver and consequently have become key drug targets for metabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and hepatic steatosis. Tao et. al. reported that the deficiency of both PDK2 and PDK4 (PDK2/4−/−) improves insulin sensitivity in DKO mice31. Similarly, Jeoung et. al. showed that inactivation of PDK2/4 in mice resulted in hypoglycemia and ketoacidosis12. This same study also suggested that these two PDK isoforms are sensitive to the nutrition states, with increased PDK2 sensitivity in the fed state and increased PDK4 sensitivity observed in the fasted state. The sensitivity of these two PDK isoforms to nutritional states was corroborated by higher levels of PDK2 and PDK4 expressions in the fed and fasted state, respectively32. Both PDK2 and PDK4 isoforms are attractive metabolic targets for pharmacological interventions to treat diabetes and obesity. Real-time evaluation of substrate metabolism as a result of double knockouts of these enzymes are therefore highly desirable.

The increased production of HP-bicarbonate from HP-[1-13C]pyruvate in livers from PDK knockout animals was readily detected by 13C NMR spectroscopy. Previous studies by Go et al. reported increased flux through PDH in PDK4 knockout livers using LCMS33. Hyperpolarized [13C]bicarbonate resulted from the decarboxylation of [1-13C]pyruvate has been used as an indicator of PDH flux26,34,35. Jin et. al. demonstrated that the detection of HP 13C-bicarbonate appearance from HP-[1-13C]pyruvate in healthy rat livers indicated the PDH activity rather than phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) or TCA cycle activity after pyruvate carboxylation26. Similarly, Cunningham et. al. showed the production of HP-13C-bicarbonate from HP-[1-13C]pyruvate for in vivo assessment of PDH flux in human myocardium36. Our results show increased HP 13C-bicarbonate signals in double PDK knockout livers, thereby confirming the sensitivity of HP 13C-bicarbonate appearance to the genetic knockout. In obese livers, knockout of PDK restored the PDH activity to a certain degree as shown by an increase in HP 13C-bicarbonate. However, neither VPDH nor HP 13C-bicarbonate was fully restored to the levels of lean DKO livers. The inability of PDK2/4 knockout to fully dephosphorylate and augment PDH activity in livers likely reflects the presence of other active PDK isoforms, for example, PDK137. It is important to point out that production of HP 13C-malate was also higher in DKO livers. This shows directly that there was an increase in flux HP 13C-pyruvate into TCA cycle intermediates via PC in PDK-deficient livers.

The Western blot and histology studies of DKO mice fed with high-fat diet confirmed the metabolic findings of NMR. These results reflect modulated PDH activity by reversible phosphorylation at Ser293 on the E1α subunit. The decreased phosphorylation of the E1α subunit (pE1) in the liver homogenate correlates well with the increase in production of HP-bicarbonate and PDH activity in the liver. As a result of increased PDH and anaplerosis fluxes, overall glucose metabolism was elevated in the liver resulting in suppression of liver steatosis via the de novo lipogenesis pathway38. It has also been recently reported that lower blood glucose levels in HFD-fed DKO mice suppress carbohydrate responsive element binding protein (ChREBP)-mediated lipogenesis39. PDK2/PDK4 double knockout is also correlated with increased energy expenditure in the HFD-fed mice. These results suggest that targeting activation of PDH is therapeutically beneficial to obese or Type 2 diabetic patients.

Taken together, our results demonstrate that the metabolism of pyruvate plays an important role in the diagnosis and prognosis of metabolic disorders. Detection of elevated hyperpolarized [13C] bicarbonate in PDK deficient livers will facilitate assessing the PDK activity in metabolic complications and determine the efficacy of new therapies targeting PDKs. We have demonstrated that MRS coupled with hyperpolarized 13C-labeled pyruvate is capable of revealing the activity of critical enzymes involving energy homeostasis, as well as assessing the PDH and associated fluxes of interest in typical hepatic metabolic diseases such as type 2-diabetes, hepatic steatosis, cirrhosis, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. It is noteworthy that detection by hyperpolarized metabolic products by NMR is rapid, noninvasive, and radiation-free and hence is entirely appropriate for translation to human patients.

Methods

Animal model and liver perfusion

The animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at UT Southwestern Medical Center. All animal procedures were performed in accordance with IACUC’s guidelines and regulations. Metabolism of HP [1-13C] pyruvate was investigated in livers from wild-type and DKO mice aged 6-8 weeks (C57BL/6 J, n = 4 per group). Four groups of mice were studied: 1. Lean control, 2. Lean DKO, 3. diet-induced obese (DIO) control, and 4. DIO DKO. Mice from DIO groups were fed ad libitum with a 60% high-fat diet containing 32% saturated and 68% unsaturated fat (Research Diet Inc., New Brunswick, NJ) for 18 weeks while the mice from lean groups were fed a standard chow diet.

Livers were catheterized, isolated, and perfused as previously described24,40. Briefly, the liver and hepatic circulatory system was exposed through a midline-laparotomy, the hepatic portal vein was cannulated, dissected and simultaneously perfused using a modified Krebs-Henseleit (KH) solution (25 mM NaHCO3, 118 mM NaCl, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4, 1.2 mM KH2PO4 and 1.25 mM CaCl2) containing 1.5 mM [U-13C]lactate and 0.15 mM [U-13C]pyruvate at a constant pressure of 25 cm-H2O. The perfusion buffer was oxygenated with a 95:5 mixture of O2/CO2. The perfusion timeline is shown in Fig. S1B. Oxygen consumption was calculated as described previously41 using efferent and afferent pO2 measurements made with a blood gas analyzer (Instrumentation Laboratory, Lexington, MA, U.S.A.). Prior to 13C NMR, shimming was carried out on the 23Na FID to obtain the linewidth of ~15 Hz, while the liver was surrounded by a sucrose flush (250 mM) to reduce the signal from extracellular 23Na. After each HP experiment, the livers were perfused an additional 15 min with the KH buffer containing 1.5 mM [U-13C]lactate and 0.15 mM [U-13C]pyruvate before the tissue was freeze-clamped.

Polarization procedure and real-time 13C NMR spectroscopy of perfused liver

[1-13C]pyruvate (4 µL) was polarized in a HyperSense polarizer (Oxford Instruments, Oxford, UK) for 2 h with 15 mM OX063 and Gadoteridol ([Gd3+] = 2 mM). The polarized sample was rapidly solubilized in a superheated KH buffer (4 mL). Three milliliters of the resultant solution was quickly mixed with 20 mL of KH buffer and injected directly into the perfused liver through a polyethylene catheter. The final concentration of HP [1-13C]pyruvate in the injected buffer was 2 mM. No other oxidizable substrates were present in this solution. A series of 13C NMR spectra were acquired every 2 s immediately after the injection of HP-pyruvate using 20-deg pulses in a 400 MHz vertical-bore NMR spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA) equipped with a 25-mm broadband probe (Doty Scientific, Columbia, SC). The spectra were zero-filled to 64k data points, Fourier-transformed, phased, and baseline-corrected. The calculated areas under the peak were normalized to the total summed peak areas of all 13C signals. The signal from pyruvate-hydrate was considered an impurity and excluded from the analysis.

High-resolution 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy of tissue extracts

Frozen liver tissues were pulverized and extracted with 5% perchloric acid. The mixture was neutralized, freeze-dried, and reconstituted in D2O containing 0.5 mM DSS (2,2-dimethyl-2-silapentane-5-sulfonate) as an internal standard and 0.1 mM EDTA. 1H NMR spectra collected with solvent-presaturation (noesypr1d) and proton-decoupled 13C NMR spectra were acquired in a 5 mm NMR tube with the temperature controlled at 37 °C using a 14.1 T Bruker Avance III HD equipped with a 10-mm cryoprobe (Bruker, MA, U.S.A.). The FIDs were zero-filled to 64k data points, Fourier-transformed, phased, and baseline-corrected using ACDLabs SpecManager (ACD/Labs, Canada). All chemical shifts were referenced to DSS set to 0 ppm.

13C NMR isotopomer assessment of hepatic metabolism

The peak areas of each glutamate C2, C3, and C4 multiplet were measured using ACD software (ACD/Labs, Canada) and used as input for performing a steady-state isotopomer analysis using tcaCALC (download available at http://www.invivometabolism.org/tca.html) as previously described42,43. Briefly, the best nonlinear least-squares fit was obtained between calculated and experimental spectra. Fractional multiplet areas measured from the fitting were used for relative flux analyses with a basic TCA cycle model first using the simplest set of metabolic fluxes (i.e. enrichment in acetyl-CoA from the labeled substrates). Additional pathway fluxes such as PC (pyruvate carboxylase, noted as YPC in the software) and PyC (pyruvate cycling, noted as PK in the software) were then included in the fitting and the overall agreement between the experimental versus calculated spectral multiplets (Fig. S4) was evaluated. In this model, PyC refers to pathways allowing conversion of a 4-carbon intermediate of the TCA cycle to pyruvate and includes oxaloacetate → phosphoenol pyruvate → pyruvate, and malate → pyruvate. For the 13C spectra of liver tissue reported here, the best fit was achieved using a model that included flux of [U-13C]pyruvate through PDH (VPDH), pyruvate carboxylase (VPC), and pyruvate cycling (VPyC). The fractional contribution of [U-13C]lactate/[U-13C]pyruvate to acetyl-CoA was obtained directly from the isotope fitting (there was a small contribution from endogenous sources of acetyl-CoA). Further, tcaCALC data were validated by spectral simulation with tcaSIM (download available at http://www.invivometabolism.org/tca.html). TCA cycle flux (VTCA) was calculated as reported previously44,45. The absolute flux values for PDH flux (VPDH), pyruvate carboxylase flux (VPC), and pyruvate cycling flux (VPyC) were obtained by multiplying the relative flux values with VTCA (Fig. S2). A ratio of VPyC/VPC + VPDH was considered as an estimate of pyruvate cycling. The ratio of lactate 13C enrichment due to pyruvate cycling (C2D23 + C2D12) to total C2 enrichment was also measured for a pyruvate cycling index.

Histopathology

Liver tissue from each group of animals was trimmed and fixed at 4 °C using 4% formalin/PBS (4% formic acid, 137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, and 10 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5) and analyzed by the histopathology core of UT Southwestern Medical Center. The tissues were incubated in 10% (w/v) sucrose in PBS for 24 h incubation at 4 °C and transferred to fresh 18% sucrose solution and frozen in optimal cutting temperature compounds (OCT), cryo-sectioned (10 µm), and stained with Oil Red- O (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Micrographs of tissue sections were taken at a magnification of 20x using an optical microscope (Leica DM2000 Upright Photomicroscope).

Western blotting

Twenty-five micrograms of protein lysate per lane were used for SDS-PAGE gels. Western blots were transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane for 2 h at 200 mV and blocked with 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dried milk. The blocked PVDF membrane was probed using polyclonal antibodies to E1α, pE1α, and GAPDH. Antibodies were prepared in the Antibody Core Facility at UT Southwestern Medical Center and affinity purified. Dilution ratios of 1:2 K, 1:25 K, and 1:10 K were used for anti-E1α, anti-pE1α, and secondary IgG detection, respectively. For signal detection, one milliliter of Luminata Forte Western HRP substrate reagent was pipetted across the membrane in a ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad, USA).

Statistical analysis

All data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism. The statistical significance for DKO groups verses their control groups were assessed by an unequal variance (Welch’s) t-test. Multiple statistical comparisons among the weight of livers were calculated using Ordinary one-way ANOVA with ‘Tukey’ post hoc analysis. P values less than 0.05 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001) were considered significant.

All data are presented as mean ± SD. Statistical significance was evaluated by two-tailed unpaired Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA wherever appropriate using GraphPad Prism (v.7). P values less than 0.05 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 and ***p < 0.001) were considered significant.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Xiaodong Wen and Thomas Hever are acknowledged for their technical support in the perfusion experiments. We thank the following agencies for financial support: NIH R37-HL034557 (ADS), NIH P41-EB015908 (CRM), NIH DK62306 (DTC), Welch Foundation I-1286 (DTC), and American Heart Association 18POST34050049 (GS).

Author contributions

C.K. designed the study; G.S., C.W., W.G. and C.K. performed experiments and analyses; D.C., C.M., and A.D.S. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; G.S., C.W. and C.K. analyzed data; and G.S., C.W., R.W., D.C., C.M., A.D.S. and C.K. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-52952-6.

References

- 1.Moller DE. New drug targets for type 2 diabetes and the metabolic syndrome. Nature. 2001;414:821–827. doi: 10.1038/414821a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel MS, Korotchkina LG. Regulation of mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex by phosphorylation: complexity of multiple phosphorylation sites and kinases. Exp. Mol. Med. 2001;33:191–197. doi: 10.1038/emm.2001.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeoung NH, Harris CR, Harris RA. Regulation of pyruvate metabolism in metabolic-related diseases. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2014;15:99–110. doi: 10.1007/s11154-013-9284-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patel MS, Nemeria NS, Furey W, Jordan F. The pyruvate dehydrogenase complexes: structure-based function and regulation. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:16615–16623. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R114.563148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gray LR, Tompkins SC, Taylor EB. Regulation of pyruvate metabolism and human disease. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2014;71:2577–2604. doi: 10.1007/s00018-013-1539-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel MS, Korotchkina LG. Regulation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:217–222. doi: 10.1042/BST20060217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wieland OH. The mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex: structure and regulation. Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol. 1983;96:123–170. doi: 10.1007/BFb0031008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holness MJ, Kraus A, Harris RA, Sugden MC. Targeted upregulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK)-4 in slow-twitch skeletal muscle underlies the stable modification of the regulatory characteristics of PDK induced by high-fat feeding. Diabetes. 2000;49:775–781. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.5.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alves TC, et al. Regulation of hepatic fat and glucose oxidation in rats with lipid-induced hepatic insulin resistance. Hepatology. 2011;53:1175–1181. doi: 10.1002/hep.24170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pesta DH, et al. Prevention of diet-induced hepatic steatosis and hepatic insulin resistance by second generation antisense oligonucleotides targeted to the longevity gene mIndy (Slc13a5) Aging (Albany NY) 2015;7:1086–1093. doi: 10.18632/aging.100854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeoung NH, Harris RA. Pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase-4 deficiency lowers blood glucose and improves glucose tolerance in diet-induced obese mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2008;295:E46–54. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00536.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jeoung NH, Rahimi Y, Wu P, Lee WN, Harris RA. Fasting induces ketoacidosis and hypothermia in PDHK2/PDHK4-double-knockout mice. Biochem J. 2012;443:829–839. doi: 10.1042/BJ20112197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang SL, Hu X, Zhang W, Yao H, Tam KY. Development of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase inhibitors in medicinal chemistry with particular emphasis as anticancer agents. Drug Discov Today. 2015;20:1112–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferriero R, Iannuzzi C, Manco G, Brunetti-Pierri N. Differential inhibition of PDKs by phenylbutyrate and enhancement of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity by combination with dichloroacetate. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 2015;38:895–904. doi: 10.1007/s10545-014-9808-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonnet S, et al. A mitochondria-K+ channel axis is suppressed in cancer and its normalization promotes apoptosis and inhibits cancer growth. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:37–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tso SC, et al. Structure-guided development of specific pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase inhibitors targeting the ATP-binding pocket. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:4432–4443. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.533885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rahimi Y, et al. Genetic activation of pyruvate dehydrogenase alters oxidative substrate selection to induce skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:16508–16513. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1419104111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serrao, E. M. & Brindle, K. M. Potential Clinical Roles for Metabolic Imaging with Hyperpolarized [1-13C]Pyruvate. Frontiers in Oncology6, 10.3389/fonc.2016.00059 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Kurhanewicz J, et al. Hyperpolarized (13)C MRI: Path to Clinical Translation in Oncology. Neoplasia. 2019;21:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neo.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Merritt ME, Harrison C, Sherry AD, Malloy CR, Burgess SC. Flux through hepatic pyruvate carboxylase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase detected by hyperpolarized 13C magnetic resonance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108:19084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111247108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno KX, et al. Production of hyperpolarized (13)CO2 from [1-(13)C]pyruvate in perfused liver does reflect total anaplerosis but is not a reliable biomarker of glucose production. Metabolomics. 2015;11:1144–1156. doi: 10.1007/s11306-014-0768-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moreno KX, et al. Real-time detection of hepatic gluconeogenic and glycogenolytic states using hyperpolarized [2-13C]dihydroxyacetone. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:35859–35867. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.613265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee P, et al. In vivo hyperpolarized carbon-13 magnetic resonance spectroscopy reveals increased pyruvate carboxylase flux in an insulin-resistant mouse model. Hepatology. 2013;57:515–524. doi: 10.1002/hep.26028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burgess SC, et al. Impaired tricarboxylic acid cycle activity in mouse livers lacking cytosolic phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:48941–48949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumashiro N, et al. Targeting pyruvate carboxylase reduces gluconeogenesis and adiposity and improves insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2013;62:2183–2194. doi: 10.2337/db12-1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jin ES, et al. Metabolism of hyperpolarized [1-(13)C]pyruvate through alternate pathways in rat liver. NMR Biomed. 2016;29:466–474. doi: 10.1002/nbm.3479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kakimoto PA, Kowaltowski AJ. Effects of high fat diets on rodent liver bioenergetics and oxidative imbalance. Redox Biol. 2016;8:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perry RJ, et al. Propionate Increases Hepatic Pyruvate Cycling and Anaplerosis and Alters Mitochondrial Metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:12161–12170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.720631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ronnebaum SM, et al. A pyruvate cycling pathway involving cytosolic NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase regulates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30593–30602. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin ES, et al. Glucose production, gluconeogenesis, and hepatic tricarboxylic acid cycle fluxes measured by nuclear magnetic resonance analysis of a single glucose derivative. Anal Biochem. 2004;327:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tao R, Xiong X, Harris RA, White MF, Dong XC. Genetic inactivation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases improves hepatic insulin resistance induced diabetes. PLoS One. 2013;8:e71997. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu P, et al. Starvation increases the amount of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase in several mammalian tissues. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;381:1–7. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.1946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Go Y, et al. Inhibition of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 2 Protects Against Hepatic Steatosis Through Modulation of Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Anaplerosis and Ketogenesis. Diabetes. 2016;65:2876–2887. doi: 10.2337/db16-0223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merritt ME, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C allows a direct measure of flux through a single enzyme-catalyzed step by NMR. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:19773. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706235104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.von Morze Cornelius, Chang Gene-Yuan, Larson Peder E.Z., Shang Hong, Allu Prasanna K.R., Bok Robert A., Crane Jason C., Olson Marram P., Tan Chou T., Marco-Rius Irene, Nelson Sarah J., Kurhanewicz John, Pearce David, Vigneron Daniel B. Detection of localized changes in the metabolism of hyperpolarized gluconeogenic precursors13C-lactate and13C-pyruvate in kidney and liver. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2016;77(4):1429–1437. doi: 10.1002/mrm.26245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cunningham CH, et al. Hyperpolarized 13C Metabolic MRI of the Human Heart: Initial Experience. Circ Res. 2016;119:1177–1182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dunford EC, et al. PDH activation during in vitro muscle contractions in PDH kinase 2 knockout mice: effect of PDH kinase 1 compensation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2011;300:R1487–1493. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00498.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hwang B, Wu P, Harris RA. Additive effects of clofibric acid and pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase isoenzyme 4 (PDK4) deficiency on hepatic steatosis in mice fed a high saturated fat diet. FEBS J. 2012;279:1883–1893. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08569.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu Cheng-Yang, Tso Shih-Chia, Chuang Jacinta L., Gui Wen-Jun, Lou Mingliang, Sharma Gaurav, Khemtong Chalermchai, Qi Xiangbing, Wynn R. Max, Chuang David T. Targeting hepatic pyruvate dehydrogenase kinases restores insulin signaling and mitigates ChREBP-mediated lipogenesis in diet-induced obese mice. Molecular Metabolism. 2018;12:12–24. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2018.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Burgess SC, et al. Diminished hepatic gluconeogenesis via defects in tricarboxylic acid cycle flux in peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1alpha (PGC-1alpha)-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19000–19008. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600050200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taegtmeyer H, Hems R, Krebs HA. Utilization of energy-providing substrates in the isolated working rat heart. Biochem J. 1980;186:701–711. doi: 10.1042/bj1860701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FM. Evaluation of carbon flux and substrate selection through alternate pathways involving the citric acid cycle of the heart by 13C NMR spectroscopy. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1988;263:6964–6971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu D, et al. 13C NMR isotopomer analysis reveals a connection between pyruvate cycling and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS) Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2002;99:2708–2713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052005699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Malloy CR, Sherry AD, Jeffrey FMH. Carbon flux through citric acid cycle pathways in perfused heart by13C NMR spectroscopy. FEBS Letters. 1987;212:58–62. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)81556-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Malloy CR, Jones JG, Jeffrey FM, Jessen ME, Sherry AD. Contribution of various substrates to total citric acid cycle flux and]anaplerosis as determined by13C isotopomer analysis and O2 consumption in the heart. MAGMA Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics, Biology, and Medicine. 1996;4:35–46. doi: 10.1007/bf01759778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.