Abstract

This study provides the first high-quality draft genome assembly (762.5 Mb) of Tenualosa ilisha that is highly contiguous and nearly complete. We observed a total of 2,864 contigs, with 96.4% completeness with N50 of 2.65 Mbp and the largest contig length of 17.4 Mbp, along with a complete mitochondrial genome of 16,745 bases. A total number of 33,042 protein coding genes were predicted, among these, 512 genes were classified under 61 Gene Ontology (GO) terms, associated with various homeostasis processes. Highest number of genes belongs to cellular calcium ion homeostasis, followed by tissue homeostasis. A total of 97 genes were identified, with 16 GO terms related to water homeostasis. Claudins, Aquaporins, Connexins/Gap junctions, Adenylate cyclase, Solute carriers and Voltage gated potassium channel genes were observed to be higher in number in T. ilisha, as compared to that in other teleost species. Seven novel gene variants, in addition to claudin gene (CLDZ), were found in T. ilisha. The present study also identified two putative novel genes, NKAIN3 and L4AM1, for the first time in fish, for which further studies are required for pinpointing their functions in fish. In addition, 1.6 million simple sequence repeats were mined from draft genome assembly. The study provides a valuable genomic resource for the anadromous Hilsa. It will form a basis for future studies, pertaining to its adaptation mechanisms to different salinity levels during migration, which in turn would facilitate in its domestication.

Subject terms: Conservation genomics, DNA metabolism

Introduction

Tenualosa ilisha (Hamilton, 1822), commonly known as Hilsa shad, belongs to Clupeidae family. It is an anadromous fish, with wide distribution in Southeast and South Asia1,2, ranging from China Sea, Bay of Bengal, Arabian Sea, Red Sea to Persian Gulf and is also found in coastal areas, estuaries and freshwater rivers3. It is commercially important due to its higher content of omega fatty acid and potential for therapeutic applications4. A recent review4 highlighted the biology, migration, ecology and genetics of Hilsa with respect to its future sustainability, however, mechanism underlying adaptation to varying salinity levels during its migration, is still not understood.

Hilsa usually inhabits coastal and estuarine waters, with varying levels of salinity (22.4–33.4 ppt)5,6. During its spawning migration, Hilsa ascends to freshwater with low salinity (approximately 0.05 ppt)5. However, for growth as well as for feeding, young ones migrate towards the sea.Thus, during its life cycle, Hilsa experiences large salinity level variations and exhibits significant physiological adaptations between hyper-osmotic seawater and hypo-osmotic freshwater environments.

Declines in production of Hilsa from natural population have raised concerns and it may probably due to over exploitation and/or change in habitat7,8. There is an urgent need for development of technology for captive breeding, seed production and culture in confined water environment. Due to its anadromous nature, the captive breeding and farm rearing has long been regarded as a difficult task. In this direction, larval rearing in freshwater has been attempted for mass production of fry to support future programmes in Hilsa aquaculture3. To understand the hatching and rearing of larvae under captive conditions, it is necessary to study underlying molecular mechanisms of adaptation to salinity fluctuations during migration for spawning and growth, in Hilsa. Thus, development of the genomic resources, which forms a basis to determine genes responsible for homeostasis and osmoregulation, becomes necessary.

During the migration, from sea to freshwater and vice versa, the anadromous fish faces challenges in osmo-regulation processes, which majorly influences the ionic homeostasis. In such a situation, a fish osmoregulatory mechanisms cope with these changes by switching/regulating ion absorption (hyper-osmoregulation) and excretion (hypo-osmoregulation)9. For the purpose, several classes of ion transporters, pumps and channels are responsible for regulating ion uptake and secretion processes10. Historical genomic events such as teleost-specific whole-genome duplication and subsequent gene-family expansions have been reported to exhibit adaptability to variations in salinity11. A variety of gene families, claudins, aquaporins and ion channels12,13, have been reported to be associated with the salinity adaptations in fishes. In migratory fishes, the claudins, which shape the tight junctions, are usually present in high copy numbers, which can be due to gene duplication event independent of whole-genome duplication in teleost fish14. Their high copy number may relate to the modulation of activities required to adjust to dramatic changes, controlling tight junctions during fish adaptation to varying osmotic and ionic gradients15. Earlier findings also indicated the role of gap junctions/connexin proteins in osmoregulation, where the abundance of alpha and beta forms of gap junction proteins were observed in the gills of freshwater and saltwater fish, respectively16. In addition, in fish gills, the adenylate cyclase activity was found to be important for salt adaptation17.

In this direction, the genomic data of Hilsa, in the form of a high quality reference genome sequence is essential, which would provide a unique resource for comparative genomics for identifying molecular mechanism related to salinity adaptation. The genomic architecture will also enable to identify novel candidate genes and pathways responsible for salinity tolerance, which would in turn be a useful resource for assisting in the captive breeding and culture of Hilsa.

In this study, we report a high-quality genome of Hilsa, assembled using data generated from long read sequencing platform and error correction using short read sequences. The present assembly of Hilsa genome spans 762.5 Mb (∼96.4% of estimated genome size) and is highly contiguous with a N50 of 2.6 Mb and largest contig length of 17.4 Mbp. We identified 33,042 protein coding genes, which represent 95.8% of the euchromatin content. From this genome assembly, the various classes of homeostasis genes were identified and through comparative genomics, species specific as well as novel genes in Hilsa were also discovered.

Materials and Methods

Sample collection

Adult T. ilisha were collected from commercial catches, from natural freshwater habitat (Padama River; N 24° 80′, E 87° 93′, Farrrakka, West Bengal, India) and euthanized with MS222 (Sigma Aldrich, USA). Tissue samples of brain, liver, gill, testes and ovary were snap frozen in liquid N2, transported to the laboratory and stored at −80 °C, until analysis.

All the protocols followed were approved by Institute Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC), ICAR-NBFGR, vide No. G/CPCSEA/IAEC/2015/2 dated 27 Oct., 2015. All the methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Genome sequencing

Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from snap frozen testes tissue via phenol-chloroform method and purified with AMPure PB beads (Beckman Coulter, Inc., CA). For long read DNA sequencing, genomic SMRT bell libraries (10 and 20 Kbp size) were prepared from purified high-quality gDNA (10 µg) (from a single specimen) using the PacBio DNA template preparation kit 1.0 (Pacific Biosciences, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) and were sequenced using P4-C2 and P6-C4 chemistry using PacBio RSII platform (Pacific Biosciences, Inc., CA). For short read genome sequencing, a total of three short-read genomic libraries, using the DNA sample prep kit, TruSeq (Illumina, San Diego, CA), were prepared from the same individual, as for PacBio sequencing and were used in paired-end (PE) sequencing (2 × 100 bp) on the Illumina HiSeq. 2500 sequencer (Illumina, CA). T. ilisha genome size was estimated by k-mer (k = 20) analysis with Jellyfish18 (version 2.2.3) using trimmed short read sequencing data. The counted K-mer was summarized as histogram and frequency distribution curve was plotted using R package19 (version R 3.5.1). Genome size was estimated as total number of k-mers/peak value of k-mer frequency distribution.

Transcriptome (Iso-Seq) sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from five tissues, brain, gill, liver, testes and ovary samples, with NucleoSpin RNAII kit (Macherey-Nagel GmbH & Co. KG) following manufacturer recommendation. First strand cDNA synthesized were used to prepare SMRT bell libraries, using DNA template preparation kit 1.0 and sequenced with P6-C4 chemistry on the PacBio RSII platform. The raw reads generated were processed by RS_IsoSeq pipeline in Pacific Biosciences SMRT analysis software v2.3.020 to classify full-length and non-full-length isoforms. All the full-length reads obtained from the same transcript isoform were clustered with Iso-Seq cluster algorithm, using a minimum (>=0.99) Quiver Accuracy21. Thereafter, the resulting consensus sequences were polished with non-full-length reads using the Quiver algorithm21.

De-novo assembly of T. ilisha genome and statistics

The genome of T. ilisha was assembled from PacBio long reads using FALCON v.0.3.0, the diploid assembly approach22. Five assembly runs were compared for the mapping of seed reads over pre-assembly with length cut-off values in FALCON ranging from 6,000 to 10,000 bp. Based on the contig N50 results, length_cut-off = 8,000 was selected for the pre-assembly step. The assembled draft genome was self-corrected (using all raw PacBio generated reads) by Quiver tool21 and was further evaluated by mapping of Illumina reads in CLC genomic workbench 9.5.323. The first round error corrected draft assembly was further error-corrected using short reads generated by Illumina platform by PILON24 tool. The final draft assembly was screened for any vector contamination using VecScreen software25. The mitochondrial sequences were separated out after BLAST searches against databases of mitochondrial sequences26. The final statistics of draft assembly was generated through QUAST27 with default parameters and was evaluated for its completeness using BUSCO v.3.028 against the Actinopterygii (actinopterygii_odb9), Vertebrate (vertebrate_odb9) and Eukaryota (eukaryota_odb9) databases, containing a total of 4584, 2586 and 303 ortholog groups, respectively.

Characterization of repetitive elements

The assembled draft genome (primary contigs) was characterized for repetitive elements using RepeatScout29. Mono to hexa-nucleotide simple sequence repeats (SSR) in the assembled genome were identified with the Microsatellite Identification tool MISA30; on default parameters. Transposable elements and miniature inverted-repeat were identified by TransposonPSI31 and TEclass32. Super families of transposable elements were predicted through MITE Digger33.

Gene prediction and annotation of nuclear genome

The assembled draft genome was masked for highly repetitive DNA sequences and low-complexity regions using the Windowmasker programme34 and used for de novo gene prediction with Augustus35 (version 3.2.3). A total of three de novo prediction sets were generated by Augustus as follows: The first set of genes was predicted at default parameters using–species = zebrafish as the model species. For the second set, Augustus was trained to use T. ilisha as the species using the evidence of complete genes from earlier BUSCO results, followed by gene prediction with–species = T. ilisha. For the third, a hints file was generated using full-length high-quality isoform reads from long-read sequencing (PacBio RSII) from 5 tissues of T. ilisha. The set of potentially predicted genes was again searched for their completeness through BUSCO transcriptome analysis module28 against the Actinopterygii database (n: 4584). A final de novo predicted gene set was generated using the hints file from Iso-seq data for further genomic characterization.

The de novo predicted genes were annotated using Blast2GOPro suite29 against SwissProt and non-redundant (nr) databases, with BlastP searches (e <10−5). Functional domains were identified by InterProScan from Blast2GOPro suite36 to identify the domains and motifs of genes against different protein databases. All genes were also annotated against Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) protein database for KEGG Orthology analysis using Blastp (e <10−5) searches via KEGG Automatic Annotation Server (KAAS)37–39. The results obtained from GO and KEGG database annotations were compared and subsequently analysed for the GO related to homeostasis and osmoregulation and genes thereon. Maximum copy number of claudins, aquaporins, gap junction/connexins, adenylate cyclase and solute carrier gene families in final predicted gene datasets were also identified. The software tRNAscan-s.e.m. v1.2340 was utilised to predict tRNA genes, with eukaryote parameters.

Orthology analysis

In order to predict conserved and unique gene families of T. ilisha, the orthologous groups were identified using the model species, Danio rerio and the migratory fishes, through Orthofinder41. Complete protein sequences of 11 fish species (Clupea harengus, Cyprinus carpio, Danio rerio, Dicentrarchus labrax, Esox lucius, Gasterosteus aculeatus, Lates calcarifer, Mororns axatilis, Oncorhynchus mykiss, Oreochromis niloticus and Salmo salar) downloaded from NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) were clustered with T. ilisha predicted genes, using standard default parameters (Suppl. Table S1).

Comparative analysis of conserved regions with other species

As the chromosome level genome structure was not available in any closely related species, comparisons of T. ilisha draft genome were performed by mapping T. ilisha contigs (length>100 Kbp) to the model fish, D. rerio (assembly GRCz11,ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes /all/GCF/000/002/035/GCF_000002035.6_GRCz11/GCF_000002035.6_GRCz11_genomic.fna.gz) using SyMap 4.242 program and to C. harengus. At the first step, genomic sequences were aligned using promer/MUMmer43 and raw anchors thus obtained were grouped into gene anchors (putative), filtered with a reciprocal top-2 filter to get input to the synteny algorithm42. As the genome assemblies of both the T. ilisha (present study) and its related species, C. harengus, are in draft level assembly, the fragments larger than 5 Mbp were included, for meaningful results from synteny analysis.

Characterization of complete mitogenome of T. ilisha

The resulting contigs from the assembled draft genome were manually searched for the presence of mitochondrial regions in BLAST26 searches against databases of mitochondrial sequences. The complete mitogenome of T. ilisha was further characterized using MitoFish and MitoAnnotator tool44.

To summarize, complete workflow for T. ilisha genome assembly and analysis has been shown in Supplementary Fig S1.

Ethical approval

All the protocols followed were approved by Institute Animal Ethics Committee (IAEC), ICAR-NBFGR vide No. G/CPCSEA/IAEC/2015/2 dated 27 Oct., 2015. This article does not contain any studies with live animals performed by any of the authors. All the samples, that were dead, were obtained from the commercial catches. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Results

Genome sequence data and genome size estimation

Through the PacBio long read sequencing approach, a 125.75x coverage (104.0 Gbp) sequence data of T. ilisha genome was generated from 10 and 20 Kb libraries. The sub-read analysis of raw PacBio reads showed N50 read length of 9,181 bp, mean read length of 6,475 bp and mean read quality score of 0.87. There were a total of 9 million subreads with sizes more than 1 Kbp (Suppl. Table S3). The short read (Illumina) libraries generated reads of 88x fold (58.70 Gb) genome coverage (Suppl. Table S3), which amounted to 501 million high-quality filtered and trimmed reads (Suppl. Table S4). The genome size was estimated as 827 Mbp, by Kmer analysis, using Illumina reads and 5.3 × 1010 (=53754844564) Kmers were found that peaked at an index value of 65.

Transcriptome data generation

Isoform sequencing (PacBio) of five tissues generated 29.0 Gb data, which included an average of 34,477 high quality full length read / tissue and range of 17429 to 57680 reads (Suppl. Table S5). Concatenating full-length reads from all the tissues resulted in a total of 172,388 reads, which were used to generate the of hints file for ab initio gene prediction.

De novo assembly of genome and quality assessment

Using long reads sequences from PacBio, the assembly statistics of 5 different assembly runs on FALCON based on varying parameters showed the resultant draft assembly sizes ranged from 757.1 to 780.5 Mbp. The primary genome assembly_5 of 762.6 Mbp size with 3052 contigs, with largest contig 14.5 Mbp, N50 2.65 Mbp and L50 83, showed best BUSCO results (85%) for genome completeness (against the Actinopterygii gene set) and was selected for further self-correction using Quiver (Suppl. Table S5). Besides the primary assembly of 3,052 contigs, an alternate haplotypes assembly of 4,046 contigs (146.3 Mbp) was also obtained. After error correction with Quiver and Pilon, final improved primary genome assembly of 2,864 contigs showed a total size of 762.5 Mbp, which is 92.2% of the estimated genome (Table 1) on which 98.85% of the total short reads (578 million reads) were successfully mapped (Suppl. Table S7). QSTAT analysis revealed the final draft assembly of 762.5 Mbp size, with an N50 of 2.6 Mbp, L50 of 83 contigs, GC content of 43.34% and largest contig length of 17.4 Mbp (Table 1). There were only 3 contigs below 1 Kbp and only one contig below 500 bp.

Table 1.

The quality statistics of the assembled genome derived from QUAST analysis of Tenualosa ilisha draft genome assembly.

| Contigs (number, >= 0 bp) | 2864 |

| Contigs (number, >= 1000 bp) | 2861 |

| Contigs (number, >= 5000 bp) | 2544 |

| Contigs (number, >= 10000 bp) | 2125 |

| Contigs (number, >= 25000 bp) | 1347 |

| Contigs (number, >= 50000 bp) | 996 |

| Total length (>= 0 bp) | 762512129 |

| Lengths of contigs (>= 1000 bp) | 762510094 |

| Lengths of contigs (>= 5000 bp) | 761416076 |

| Lengths of contigs (>= 10000 bp) | 758288005 |

| Lengths of contigs (>= 25000 bp) | 745674646 |

| Lengths of contigs (>= 50000 bp) | 733352674 |

| Lengths of contigs (>= 500 bp) | 2863 |

| Largest contig (bp) | 17427296 |

| Percentage of GC | 43.34 |

| N50 (bp) | 2624235 |

| L50 (bp) | 83 |

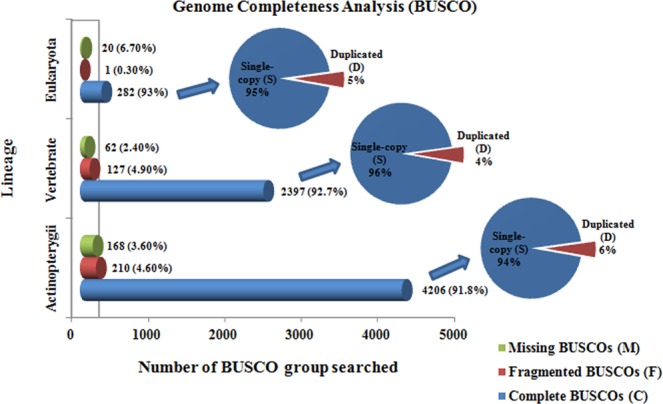

A genome completeness analysis of the final draft assembly of T. ilisha against 3 BUSCO databases (Eukaryota, Actinopterygii and Vertebrata) showed a high estimate of genome completeness i.e., 96.4% (91.8% complete + 4.6% fragmented BUSCOs), with only 3.6% missing BUSCOs (Fig. 1). The detailed statistics with 3 analysed BUSCO databases are given in Suppl. Table S8.

Figure 1.

BUSCO analysis to assess the completeness of T. ilisha draft genome in comparison to highly conserved core genes of Actinopterygii, Eukaryota and Vertebrata.

Repeat elements

A 12.92% of the present draft genome assembly of T. ilisha contain repetitive elements, which is about 90.63 Mbp and both tandem and interspersed repeats (Suppl. Table S9) were observed, among them majority are microsatellites (64 Mbp; 8.39%). A total of 1,785,618 SSRs were obtained across the genome (Suppl. Table S10). Out of total 2,867 contigs, 2,196 (76.5%) were found to contain SSR and 2,038 of these had more than one SSR. Among these identified SSRs, di-nucleotide SSRs (84.6%) were most abundant (1,977 SSR/Mbp) and densely placed (3,954 bp/Mbp) (Suppl. Fig. S2). Two contigs contain telomeric repeats (TTAGGG)n, covering 13.4 Kbp. These two contigs are contig00000F841; total length of 70.737 Kbp and contig00000F1661; total length of 17.437 Kbp. Transposable elements were found to belong to 14 super-families, covering 1% genome (Suppl. Table S11). Details about other classes of transposable elements and tRNA are given in Suppl. Tables S12, 13.

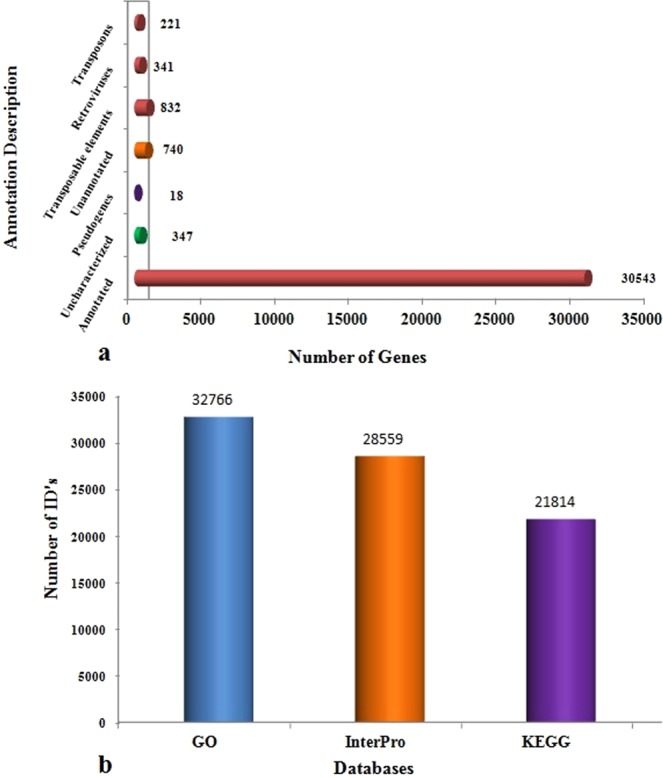

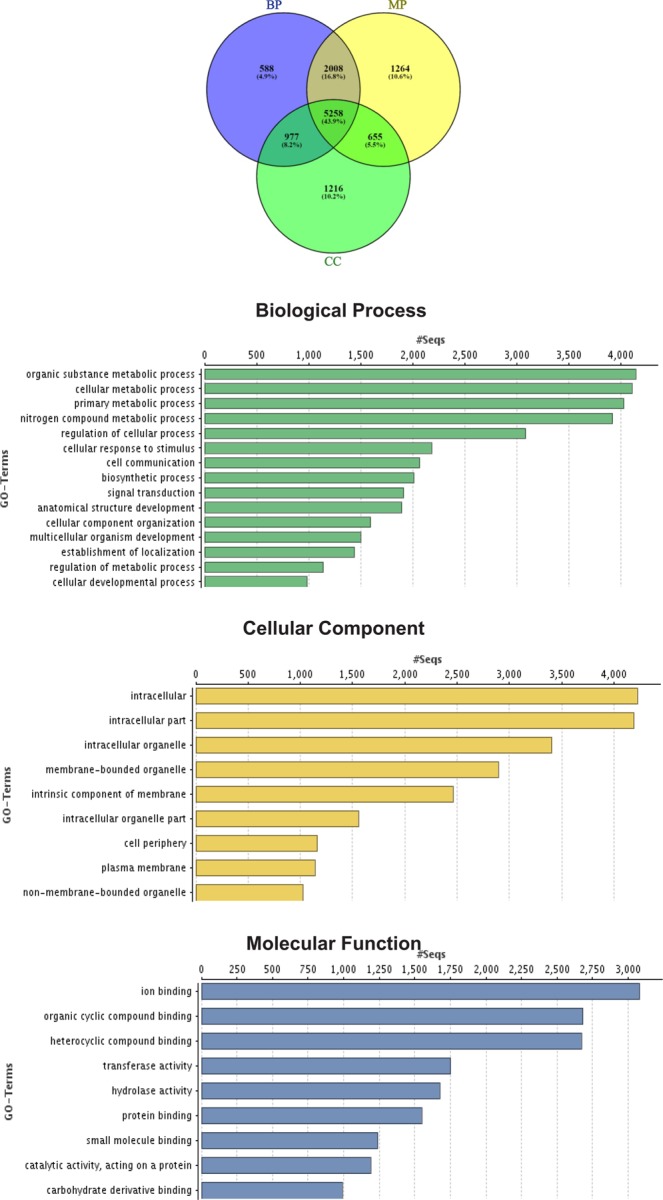

Gene prediction and functional annotation

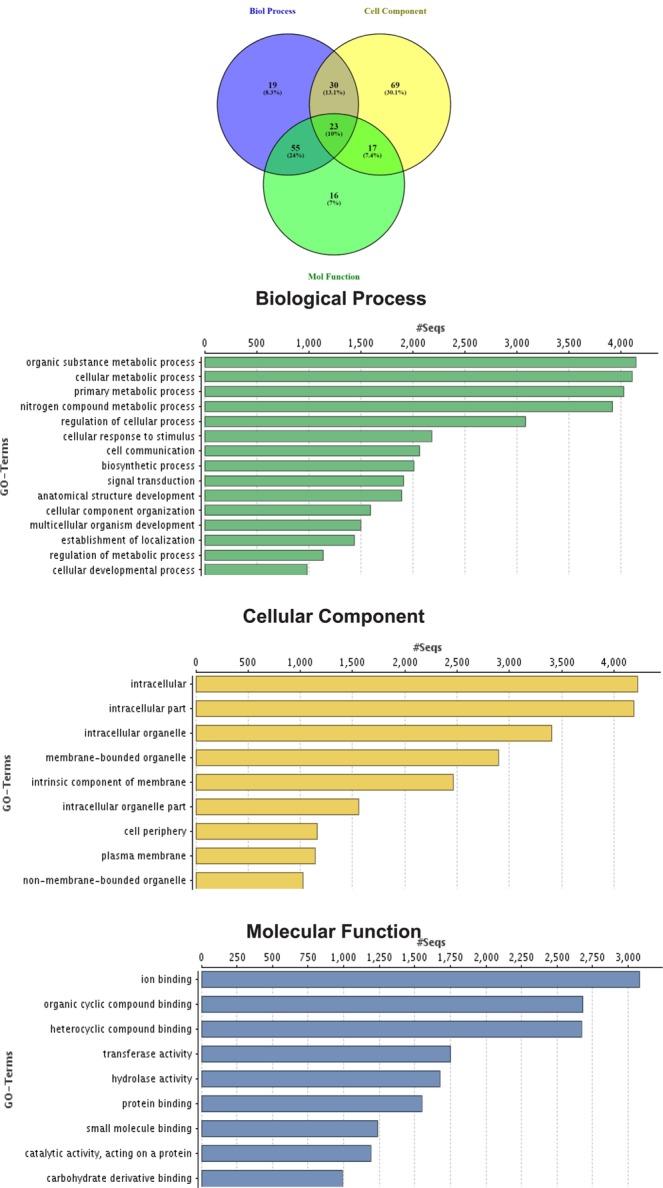

Evidence-based ab initio gene predictions with Augustus predicted 33,042 protein coding genes and BUSCO results indicated 95.8% (87.1% Complete and 8.7% Fragmented) of the core genes to be present (Suppl. Table S14).And 96.66% (31,937) predicted genes were annotated with both the databases (nr and SwissProt). The remaining 1.05% (347) genes were uncharacterized/unidentified protein families and 0.05% (18) pseudo genes, while 2.2% (740) genes remained unannotated (Fig. 2: Suppl. Table S15). Analysis of Gene Ontology (GO) terms revealed that GO terms were assigned to 32,766 genes and 4.9% of GO terms were found to be unique to biological processes, 10.2% in cellular functions and 10.6% in molecular processes, while 43.9% were shared by all the three categories (Fig. 3). InterPro analysis revealed 28,559 genes with significant hits, while the high number of genes was associated with protein families from the PFAM database (26,582), as compared to other four databases.

Figure 2.

Number of Annotation of the predicted genes from T. ilisha draft genome (a) under different categories and (b) through different databases.

Figure 3.

Gene Ontology (GO) functional annotations of predicted genes represented by three categories- 8831 genes were assigned with GO terms in Biological process, 9185 genes in Molecular Function and 8106 genes in Cellular component. Each category is sub-categorized in different GO terms, represented on y-axis and numbers of genes are shown in x-axis.

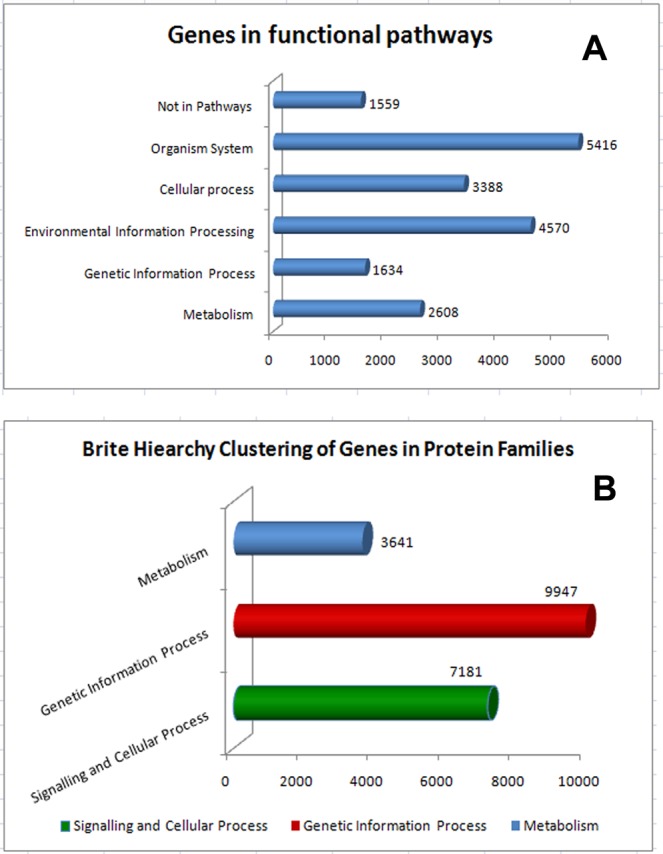

The KEGG analysis classified sequences majority into three protein families, metabolism (3,641 genes), genetic information processing (9,947) and signaling and cellular process (7,181) (Fig. 4). A total of 22,549 genes in KEGG pathways were assigned with 8,6147 unique KEGG Orthology (KO) numbers. These genes were functionally categorized into 5 major KO categories: Metabolism (2608 genes; 13%), Genetic information processing (1634; 8%), Environmental information processing (4570, 24%), Cellular processes (3,388; 18%) and Organismal Systems (5416, 28%). However 1659 (9%) genes with KO terms could not be assigned to any major categories. The GO and KO results were further mined for the genes related to osmoregulatory processes.

Figure 4.

(A) Genes categorized into different pathways in KEGG’s analysis. Majority of genes categorized into Organismal System (GIP) pathways of KEGG’s orthology. (B) Brite hierarchy clustering of KEGG annotated genes into different protein families.

Genes associated with homeostasis

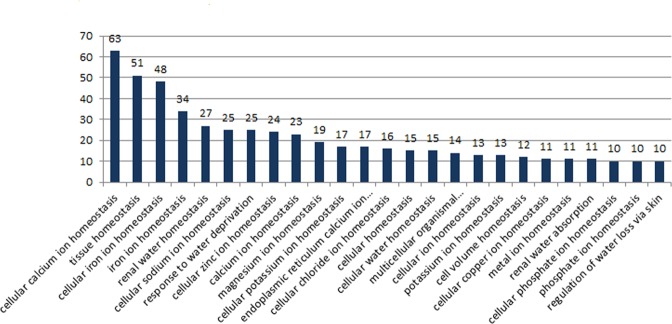

On the basis of functional annotations, 61 GO terms were found to be associated with homeostasis and included 512 genes (Figs 5, 6; Suppl. Tables S16, 17), which include ion and water homeostasis. Among these, highest number of genes (63) were under cellular calcium ion homeostasis (GO: 0006874), in which there were 9 copies of Kinase C-beta type gene, while 6 copies each were found for glutamate receptor kainate 2 and sodium potassium calcium exchanger 3 (Suppl. Table S18). Next highest number (51) of genes was found in GO:0001894: tissue homeostasis, includes, besides many other genes, highest number of 6 copies for CYR61 and 5 for COL2A1 genes (Suppl. Table S19). A total of 48 genes was categorised under cellular iron ion homeostasis (GO:0006879), majority of which are ATP-binding cassette Sub-family B and G members and Transmembrane protein serine 6 and 9, with multiple copies (Suppl. Table S20). Under water homeostasis, 97 genes were found, under which important GO: renal water homeostasis (GO:0003091) contains 27 genes, followed by response to water deprivation (GO:0009414, 25 genes), cellular water homeostasis (GO:0009992, 15 genes) and renal water absorption (GO:0070295, 22 genes). Renal water homeostasis (GO:0003091) also includes eight genes of adenylate cyclase, with multiple copies, highest of which is of ADC48 (9 copies) (Suppl. Table S21). Genes identified under water homeostasis are given in Suppl. Table S21.

Figure 5.

Genes associated with homeostasis functions categorized through Gene Ontology (GO) analysis in from total genes predicted from Tenualosa ilisha genome assembly.

Figure 6.

(A) Vann diagram showing GO Functional annotations of homeostasis related genes that were unique for and shared by three categories. (B) Gene ontology terms for (a) biological process (b) cellular components (c) molecular function for top 50 GO Terms from 512 genes with homeostasis functions in Tenualosa ilisha.

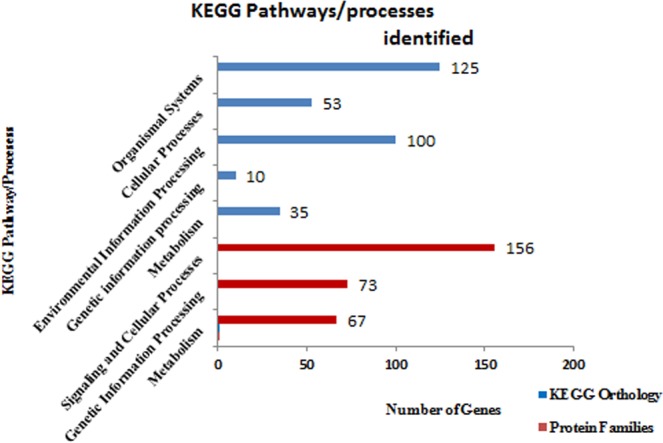

Among these 512 genes with GO terms related to homeostasis, analysis of KEGG pathways resulted in majority (125) genes under organismal systems, followed by environmental information processing (100) (Fig. 7; Suppl. Table S22). Lipid and carbohydrate metabolism contained maximum number of genes (10 each), while signal transduction pathway (89 genes) and signalling molecules and interaction (30 genes) came out as the most crucial pathways in T. ilisha homeostasis. Signal transduction pathways includes Ras signalling pathway [PATH:ko04014] with 13 genes (Suppl. Fig. S3), followed by Rap1 signalling pathway [PATH:ko04015] with 10 genes (Suppl. Fig. S4). Other pathways with 7 genes each were Calcium signalling pathway [PATH:ko04020] (Suppl. Fig. S5) and FoxO signalling pathway [PATH:ko04068]. It was interesting to find four genes, i.e., PIK3CA_B_D (phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha/beta/delta) gene with 4 copies, PRKCA (classical protein kinase C alpha type, 2 copies), PKA (protein kinase A, 4 copies) and CAMK2 (calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (CaM kinase) II, 4 copies) and adenylate cyclases (ADCY1,2,3,6,8,9) participate in almost all the signalling pathways.

Figure 7.

KEGG pathways/processes identified for homeostasis functions in Tenualosa ilisha.

Digestive (54 genes) and endocrine (48 genes) system were prominent among the Organismal Systems pathways. In digestive system, genes of osmoregulatory nature were placed among bile secretory pathway (16 genes), gastric acid secretion (23 genes) and bile secretion (17 genes) (Suppl. Table S23), among which membrane bound proteins like solute carriers, ATP4B (H+/K+-exchanging ATPase subunit beta), Aquaporins and ATP-binding cassettes (MRPs) were found. Under the endocrine system, the pathway of Parathyroid hormone synthesis, secretion and action has maximum (23) number of osmoregulatory genes (Suppl. Table S25). While in excretory system (Suppl. Table S25), pathways like Aldosterone-regulated sodium re-absorption, endocrine and other factor regulated calcium absorption and vasopressin-regulated water re-absorption play major roles, with 9 genes in each pathway, where ATP1B/CD298 (sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit beta, 5 copies) being prominent in 4 pathways. Pathways for communication between the cells, which include Focal adhesion [PATH:ko04510], Adherens junction [PATH:ko04520], Tight junction [PATH:ko04530] and Gap junction [PATH:ko04540], contain 34 homeostasis genes.

In addition, among the homeostasis processes, largest number of genes belonged to Adenylate cyclase (ACD, 8 genes with total 22 copies), Aquaporins (AQP, 9 genes, 21 copies), solute carrier gene (SLC, 16 families, 34 genes, 61 copies) and voltage gated potassium channel gene (45 genes, 135 copies) families (Suppl. Table S26). The present study also identified a considerable number of claudins (CLD) encoding genes (23 genes, 68 copies) and gap junction/connexin (CX) coding genes (21 genes, 55 copies) in the T. ilisha genome assembly.

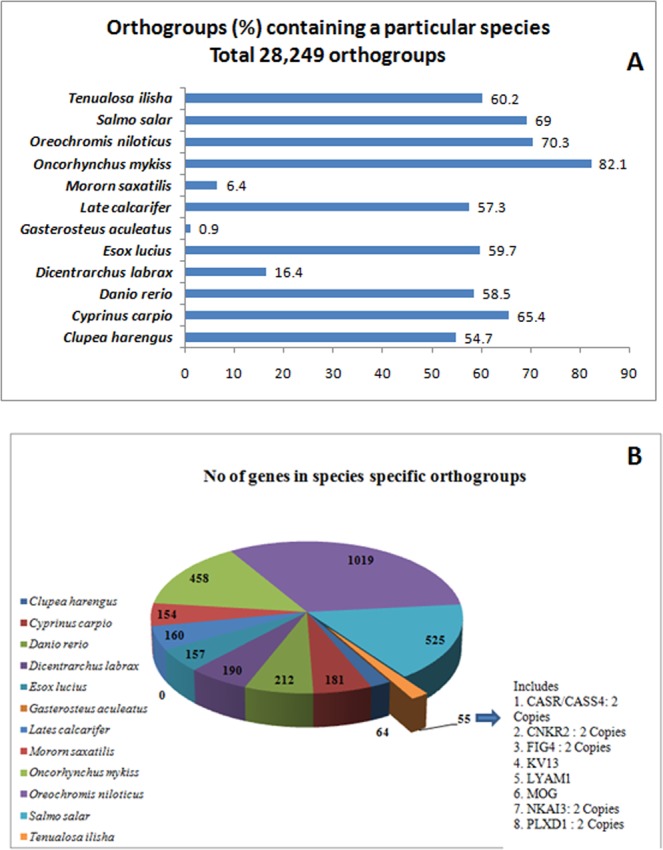

Conserved and unique gene/protein families

Among the 12 analysed fish proteomes, including that of T. ilisha, a total of 28,249 common and 518 species specific orthogroups were identified among all selected species (Suppl. Table S27). Proteins from T. ilisha were included in 17,015 common orthogroups (Fig. 8a) and T. ilisha specific 18 orthogroups contain 55 proteins (Suppl. Table S28).

Figure 8.

(A) Common orthogroup from the comparison of total proteins from 12 fish species, including Tenualosa ilisha. (B) Species specific orthogroup in Tenualosa ilisha, which included novel variants and new genes.

Among these 55 proteins (Table S29), interestingly 2 genes, NKAI3 (Sodium potassium-transporting ATPase subunit beta-1-interacting 3) and L4AM1 (L-selection) are reported here, for the first time in fish. The remaining are novel variants of genes, already known in literature, which included variants for seven genes (Fig. 8b; Supp. Table S30). Among them, CASR/CASS4, CNKR2 and FIG4 have 2 copies each, while KV13, LYAM1, MOG and PLXD1 one each.

Orthology analysis of four (ACD, AQP, CLD, CX) osmoregulatory related gene families with 43 other fish species (Suppl Table S2) revealed that most of the fish species have highly similar orthogroups, based on these genes. Comparison of claudin genes of 43 fish species revealed that majority of the species have all their Claudin genes designated in orthogroups. However, one species-specific orthogroup of T. ilisha emerged, which contained 2 CLDZ genes. For other three gene families, no species-specific T. ilisha orthologous group was observed, although, sufficient number of fish species was used for analysis.

Comparative genomics through synteny analysis

The synteny analysis of T. ilisha draft genome and chromosomal level assembly of the model fish species, Danio rerio resulted in mapping of 660 sequences from T. ilisha (>100 Kbp size) over Danio rerio (25 chromosomes), with 174 synteny blocks (Suppl. Fig. S6). Further, comparisons of T. ilisha assembly with its closest species, C. harengus, showed the mapping of a total of 19 sequences of C. harengus on 23 of T. ilisha (36% mapped) (Suppl. Table S30, Fig. S7). Maximum hits (1,051) were found between T. ilisha contig_2778 and C. harengus contig_2741, with Pearson R value of 0.99919 (Suppl. Fig. S8).

Mitochondrial genome of T. ilisha

The complete mitogenome of T. ilisha was found to be composed of one contig, of length of 16,745 bases, contains 13 protein-coding genes. Non-protein coding regions include 2 ribosomal RNA, 22 tRNAs and a D-loop region (Suppl. Table S32). The genes arrangement was found to be typical of fish/vertebrate mitogenomes. All the genes were encoded on the heavy strand, except for ND6 and eight tRNA genes.

Discussion

The present study reports the first high-quality draft genome assembly of Hilsa shad, T. ilisha, from the family Clupeidae (Order Clupeiformes). The estimated genome size of 827 Mbp is in good agreement with that of another member of Clupeidae family, Clupea harengus (808 Mbp)45 and other herrings (http://www.genomesize.com).

We have successfully generated T. ilisha draft genome assembly of 2,864 highly contiguous contigs (762.5 Mbp) with a high N50 than reported in earlier studies46,47. Moreover, the genome assembly from the present study shows a high completeness and its GC% is similar to that reported for other teleosts45,48,49. In addition, it shows high synteny and co-linearity with the model species, D. rerio as well as with C. harengus. However, it was surprising to find the repeat content in T. ilisha to be significantly lower than that in C. harengus, which may be due to absence of tandem repeats rich telomeric regions50 in the present genome assembly. However, the high percentage (95.8%) of core genes suggests its high level completeness of euchromatin components. In addition, the long reads hint file efficiently predicted a high proportion of full-length genes, as accurate start and stop codons were made available for gene predictions.

Interestingly, the T. ilisha specific orthogroup, with 55 gene sequences, contains two genes, NKAIN3 and L4AM1, which are reported here for the first time in fish. NKAIN3 has been reported as a family of mammalian proteins with an orthologue in Drosophila melanogaster51. Its functions are yet to be defined, but its important role for neuronal function by interacting with the beta subunit of Na,K-ATPase is speculated51. In human, NKAIN3 gene is reported to express in foetal temporal lobe of the brain51 and its variant was found to be associated with cognitive traits. L4AM1 (L-selectin, also known as CD62L) belongs to a family of adhesion/homing receptors and is responsible for Ca2+ ion dependent cell to cell adhesion52. Along with the gap junctions, it links plasma membranes of adjacent cells53.

Among T. ilisha specific orthogroup members, the genes, for which novel variants are identified, are involved in signalling processes, i.e. FIG4 54 and Plexin D155 play key roles in vesicle trafficking and latter in regulating the migration of wide spectrum of cell types, respectively. CASR is a receptor for sensing the signal of calcium ion entracellular levels, controls calcium homeostasis, by regulating the release of parathyroid hormone56. CASS4 has a role in signalling related to cell and focal adhesion integrity56 and KV13 mediates voltage dependent ion membrane permeability (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/3738). CNKR2 mediates the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways downstream from Ras (https://www.genecards.org/cgi-bin/carddisp.pl?gene=CNKSR2), while MOG (Myelin-oligodendrocyte glyco protein) mediates homophilic cell-cell adhesion57.

Fish have evolved the mechanisms to face the challenges, due to the aquatic environment, for maintaining their internal ion homeostasis, against the external ionic gradients. Although the kidneys form a major organ for osmoregulation, the integument, gills and intestine also play important roles, to maintain ion and water homeostasis9. In general, euryhaline fishes adopt the strategy of dynamic control through hypo- and hyper-osmoregulation9.

In hilsa shad, on the basis of their functions related to homeostasis, we found highest number of genes, for cellular calcium ion homeostasis, as compared to other GOs. Fish fulfills all its requirement of Calcium (Ca+2) from water and many fish species are known to adjust to varying calcium concentrations in water. Among the genes under this category, the highest number of copies were found for Kinase C-beta type (PRKCB) gene (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gene/5579), followed by sodium potassium calcium exchanger 3 (NCKX3, SLC24A3). PRKCB is a member of serine- and threonine-specific protein kinases family and is involved in expression of Claudin proteins, which are responsible for tight junction membrane permeability58. NCKX3/ SLC24A3 functions in the transport of intracellular calcium across the cell membrane in exchange for extracellular sodium ions and is expressed in many tissues, including, intestine59, as well as in kidney60 for osmoregulation of body fluids. Pinto et al.61 studied gill transcript expression patterns in green spotted puffer fish for different [Ca2+] and suggested occurrence of cytoskeletal proteins active re-modeling during the initial acclimation process.

Another class of genes, ATP-binding cassette or ABC, identified under cellular iron ion homeostasis in T. ilisha were found in multiple copies. These are trans-membrane transporter proteins and with the help of ATP, are involved in transportation of several types of molecules across cellular membranes62. In human, several of ABC proteins have been reported to involved in lipid homeostasis63. In trout, multiple copies of trans-membrane protein serine genes were reported and ATP-binding cassette sub-family F member 1 (ABCF1) was found to be up-regulated in freshwater ionocytes64. In tissue homeostasis, presence of multiple homologues of CYR61 (CCN1) was reported and was predicted to be involved in cell adhesion and negative regulation of cell death65 in zebra fish.

The kidney is an important organ in euryhaline fish, for ion homeostasis and osmoregulation of body fluids during the process of adaptation to various salinities66. In Hilsa, Under water homeostasis category, highest number of genes were found in renal water homeostasis, which may be the indication of importance of this process in Hilsa. Adenylate cyclases are known osmosensors and their role in osmoregulation is well known67 (discussed in detail in later section). Prolactin, a pituitary hormone, is known to be required for fresh water-adaption in fish68. Hormones of Vasopressin-V2-type receptor-aquaporin axis control the extra- and intra-cellular fluid osmoregulation69.

The present study observed AQP, SLC and voltage gated potassium channel gene families in multiple copies, which are related to homeostasis, including osmoregulation. The indirect role of adenylate cyclase and aquaporins, as osmosensors, has been reported in euryhaline fishes for regulating osmoregulatory mechanisms against salinity stress67 and were suggested to have arisen from the early duplication events of the ancestral genes70. In Atlantic salmon, six isoforms of Aquaporins ie., AQP-1a,b; 3a; 8a,b and 10a were differentially expressed in different salinity levels in gill and intestine, however, AQP-8b was suggested to be a key water channel responsible for water uptake in the intestinal tract of seawater salmonids71.

Solute Carrier (SLC) transporters are secondary transporters, which control trans-membrane movement of important substrates and 338 putative genes in 50 families are reported in fishes, which are important for cellular influx and efflux72. Out of eight transporter families reported to be involved in the processes to enable fish to tolerate different salinity levels72, Hilsa possesses six families. Four members of Na+/(Ca2+-K+) exchanger family, SLC24 (homologue NCKX in human), i.e. a1, a3 and a572 and a273 have been reported in fish. It is interesting to find the presence of 4 members, a2, a3, a4 and a6 in Hilsa, of which a6 is being reported for the first time in a fish species, whose homologues is found in human74. SLC24a6 has been reported to play a role in different tissues and cell types for K+-dependent Na+/Ca2+ exchange in maintaining cellular Ca2+ homeostasis75. Further, SLC5a8, 34a, 6a15, 2a5, 43a3 and 39a4 were reported to be responsive to osmoregulation as well as salinity stress in the liver of spotted sea bass76 and SLC13a1 and SLC26a1 to freshwater osmoregulation77

Proteins involved in K+ voltage-gated channels are also found in multiple copies in the present study. These are reported to be responsive to changes in voltage of cell membrane and are involved in several functions, including transportation of K+ across basolateral membranes78 and volume regulation79. However, not much is known about their detail functions in teleosts. These channel transcripts have been detected in the intestinal epithelium80 and in gills81.82 from various fish species. In Atlantic Salmon gills, regulation of expression of BK channel during acclimation to different salinity levels suggested their possible role in osmoregulation81–83. In Hilsa, involvement of a particular gene(s), from the multiple genes reported here, can be pinpointed after the experimentation with different salinity levels.

Claudins and gap junction/connexin proteins encoding genes are involved in tight and adherens junctions of epithelial cells and control the exposed epithelia permeability at the time of salinity changes15. Their high copy number may relate to the modulation of activities required to adjust to the dramatic changes, controlling tight junctions, during fish adaptation to varying osmotic and ionic gradients15. The presence of multiple claudins in T. ilisha (68) exceeds the number of previously reported in European seabass (61), stickleback (57), tilapia (56), fugu (56), zebrafish (54), medaka (48) and Atlantic cod (47)11,15,84. Role of isoforms of Claudin 6, 8, 10, 15 and 27 have been reported for acclimation to freshwater and seawater adaptation in fish85–88. Orthology analysis of specific osmo-regulatory genes revealed a variant of Claudin in T. ilisha, CLDZ gene with two copies, which has been reported to be responsive to nociceptive events in fish89.

Likewise, a larger number of connexin protein-encoding genes are represented in the present genome (53) compared to 39 to 40 reported in other teleost fishes, i.e., zebrafish, herring, catfish, fugu, tilapia, and medaka90,91. Connexins are integral membrane proteins that oligomerize to form gap junctions (proteinaceous channels) that permit the transfer of small molecules (<1 kDa) between neighboring cells. It is interesting to find presence of Cx33, which is single “mouse-specific” connexin92 and is a testis-specific gap junction protein93. It is absent both from the human genome and zebrafish genome. Cell adhesion and tight junction proteins are quickly up-regulated in response to hypo-osmotic shock and transcripts for proteins connexin-32.2, claudin-3, and claudin-4 were reported to be up-regulated in Killifish94.

In T. ilisha, the presence of multiple copies of genes may suggest expansions of these genes for adaptation to extreme environmental conditions, independent from the proposed whole genome duplication in teleost fish14, and may provide the genomic landscape for the anadromous lifestyle in T. ilisha. Moreover, adaptation by a euryhaline fish to changing environmental salinity is an energy expensive process and for iono- and osmo-regulation, metabolic pathways plays a significant role in the energy supply95. In present study, homeostasis genes were also found in Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism pathways, which play a significant role in energy supply. As a migratory fish requires lower energy in acclimation to low salinity water than that in high salinity96, these metabolic pathways may play a significant role in hilsa migration from fresh to marine environment for growth.

To sense the changing environment, T. ilisha seems to transduce stimulus to signalling pathways, which in turn activates the specific changes required for osmoregulation, as signal transduction pathway and signalling molecules and interaction seems to be the most crucial pathways in T. ilisha. Differential response of cell stress pathway genes, triggered by osmotic change, results in up-regulation of cell cycle and signal transduction has been reported in euryhaline fish97. Among the organismal systems pathways, involvement of membrane bound proteins with homeostasis function seems most prominent in digestive and excretory system of T. ilsha, while in endocrine system, pathways supporting for ion- and water reabsorption seems significant. This is quite reasonable to consider that under various osmotic conditions, the upkeep of intracellular homeostasis necessitates significant activities by these trans-membrane systems.

Conclusions

The assembly and analysis of the genome of an organism provides a most important link to understanding the biology, ecology and adaptations of that species. Although the draft genome of T. ilisha, in the present study, is fragmented, however it is highly contiguous with a high N50 than that reported in earlier studies46,47. This high-quality draft genome with nearly complete euchromatin and predicted genes, especially those with homeostasis and osmoregulatory function, form an important genomic resource in the species. This resource can accelerate scientific investigations of important traits in Hilsa, particularly for its adaptive mechanisms for facing varying salinity levels during the migrations.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Director, ICAR-NBFGR, Lucknow, India for providing facilities for this work. This work was carried out under ICAR Consortium Research Platform on Genomics (ICAR-CRP Genomics) and financial assistance by ICAR-CRP Genomics is duly acknowledged. We acknowledge Dr. Achal Singh for his help in estimating the genome size from Illumina data, Mr. Rakshit Chaudhary, Mr. Trivesh Mayekar and Dr. B. Kushwaha in initial genome assembly and Dr L. Mog Chowdhury and Mr. Rajesh Kumar Maurya for help during manuscript revision.

Author contributions

V.M., J.K.J. and T.M. conceived concept, V.M. J.K.J. designed the experiments, T.D., R.K.T. and R.K. performed the experiments, V.M., T.D., R.K.T. and R.K.S. analyzed the genomic data, V.M. and J.K.J. contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools,: V.M., T.D., R.K.T., R.K., R.K.S., J.K.J. and T.M. discussed the results. V.M., T.D., R.K.T., R.K.S. and J.K.J. wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Data availability

The raw PacBio reads are available through the Short Read Archive (SRA) database (SRP126802) of NCBI under Bioproject (PRJNA422030) and Bio-Sample (SAMN08162886). This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession PYXC00000000. The version described in this paper is version PYXC01000000, includes primary and alternate contigs. The raw sequence reads from Illumina sequencing were submitted to NCBI, SRA database (SRR 6384292, SRR6384293 and SRR6384294) under Bioproject (PRJNA422030) and Bio-Sample (SAMN08195513). The raw iso-seq reads of PacBio RSII were submitted to SRA database under Bioproject (PRJNA417747). SRA and BioSample Accessions were provided in Table S5.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-52603-w.

References

- 1.Sahoo AK, et al. Breeding and culture status of Hilsa (Tenualosa ilisha, Ham.1822) in South. Asia: A review. Rev. Aquacult. 2016;10:96–110. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mandal S, et al. Comparative length-weight relationship and condition factor of Hilsa Shad, Tenualosa ilisha (Hamilton, 1822) from freshwater, estuarine and marine environments in India. Indian J. Fish.s. 2018;65:33–41. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chattopadhyay D, et al. Larval rearing of hilsa shad, Tenualosa ilisha (Hamilton 1822) Aquac. Res. 2018;50:778–78. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutta S, Hazra S. From biology to management: A critical review of Hilsa Shad (Tenualosa ilisha) Indian J. Geo-Mar.Sci. 2017;46:975–1033. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barat A, Punia P, Ponniah AG. Karyotype and localization of NOR in threatened species, Tenualosa ilisha (Ham.) (Clupeidae: Pisces) Chromosome Sci. 1996;II-82:2828–2832. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ali, A. D., Naser, M. N., Bhaumik, U., Hazra, S. & Bhattacharya, S. B. Migration, Spawning Patterns and Conservation of Hilsa Shad (Tenualosa ilisha) in Bangladesh and India. Published by Academic Foundation India, New Delhi and International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), 95 (2014).

- 7.Mohindra V, et al. Genetic population structure of a highly migratory Hilsa Shad, Tenualosa ilisha, in three river systems, inferred from four mitochondrial genes analysis. Environ. Biol. Fish. 2019;102:939–954. doi: 10.1007/s10641-019-00881-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bhaumik U. Fisheries of Indian Shad (Tenualosa ilisha) in the Hooghly–Bhagirathi stretch of the Ganga River system. Aquat. Ecosyst. Health. 2017;20:130–139. doi: 10.1080/14634988.2017.1283894. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kültz D. Physiological mechanisms used by fish to cope with salinity stress. J Exp Biol. 2015;218(12):1907–1914. doi: 10.1242/jeb.118695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dutta S, Ray SK, Pailan GH, Suresh VR, Dasgupta S. Alteration in branchial NKA and NKCC ion-transporter expression and ionocyte distribution in adult Hilsa during up-river migration. J. Comp. Physiol. B. 2019;189:69–80. doi: 10.1007/s00360-018-1193-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tine M, et al. European sea bass genome and its variation provide insights into adaptation to euryhalinity and speciation. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:5770. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larsen PF, et al. Differences in salinity tolerance and gene expression between two populations of Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua) in response to salinity stress. Biochem. Genet. 2012;50:454–466. doi: 10.1007/s10528-011-9490-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tingaud-Sequeira A, et al. The zebrafish genome encodes the largest vertebrate repertoire of functional aquaporins with dual paralogy and substrate specificities similar to mammals. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010;10:38. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Loh YH, Christoffels A, Brenner S, Hunziker W, Venkatesh B. Extensive expansion of the claudin gene family in the teleost fish, Fugu rubripes. Genome Res. 2004;14:1248–1257. doi: 10.1101/gr.2400004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelund MB, et al. Functional characterization and localization of a gill-specific claudin isoform in Atlantic salmon. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2012;302:R300–R311. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00286.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lam SH, et al. Differential transcriptomic analyses revealed genes and signaling pathways involved in iono-osmoregulation and cellular remodeling in the gills of euryhaline Mozambique tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:921. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guibbolini ME, Lahlou B. Adenylate cyclase activity in fish gills in relation to salt adaptation. Life Sci. 1987;41:71–78. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(87)90558-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marçais G, Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:764–770. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.RCore Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2013).

- 20.Gordon SP, et al. Widespread polycistronic transcripts in fungi revealed by single molecule mRNA sequencing. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0132628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chin CS, et al. Nonhybrid finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:563–569. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.PacificBiosciences/FALCON-integrate, https://github.com/PacificBiosciences/FALCON-integrate.

- 23.CLC genomic workbench 9.5.3, https://www.qiagenbioinformatics.com.

- 24.Walker Bruce J., Abeel Thomas, Shea Terrance, Priest Margaret, Abouelliel Amr, Sakthikumar Sharadha, Cuomo Christina A., Zeng Qiandong, Wortman Jennifer, Young Sarah K., Earl Ashlee M. Pilon: An Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(11):e112963. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.VecScreen: Screen a Sequence for Vector Contamination, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/vecscreen.

- 26.Geer, L.Y. et al. The NCBI BioSystems database. Nucleic Acids Res. 38 (Database issue):D492-6, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N. & Tesler, G. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics29, 1072–1075 http://quast.sourceforge.net (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Simao FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–3212. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:i351–i358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beier S, Thiel T, Münch T, Scholz U, Mascher M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2583–2585. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.B J. Haas TransposonPSI, 2007–2011, http://transposonpsi.sourceforge.net.

- 32.Abrusan G, Grundmann N, DeMester L, Makalowski W. TEclass - a tool for automated classification of unknown eukaryotic transposable elements. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1329–1330. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang G. MITE Digger, an efficient and accurate algorithm for genome wide discovery of miniature inverted repeat transposable elements. BMC Bioinformatics. 2013;14:186. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Windowmasker programme, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/IEB/ToolBox/CPP_DOC/lxr/source/src/app/winmasker.

- 35.Stanke M, et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucl. Acids Res. 2006;34:W435–W439. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gotz S, et al. High-throughput functional annotation and data mining with the Blast2GO suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:3420–3435. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Furumichi M, Morishima K, Tanabe M. New approach for understanding genome variations in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D590–D595. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kanehisa M, Tanabe M, Sato Y, Morishima K. KEGG: new perspectives on genomes, pathways, diseases and drugs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D353–D361. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16:157. doi: 10.1186/s13059-015-0721-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soderlund, C., Nelson, W., Shoemaker, A. & Paterson, A. SyMAP: A system for discovering and viewing syntenic regions of FPC maps. Genome Res. 16, 1159–1168, Online available at, http://www.agcol.arizona.edu/software/symap/ (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Delcher AL, Phillippy A, Carlton J, Salzberg SL. Fat Algorithms for large scale genome announcement and comparison. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2478–2483. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.11.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Iwasaki W, et al. MitoFish and MitoAnnotator: A mitochondrial genome database of fish with an accurate and automatic annotation pipeline. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013;30:2531–2540. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barrio AM, et al. The genetic basis for ecological adaptation of the Atlantic herring revealed by genome sequencing. Elife. 2016;5:e12081. doi: 10.7554/eLife.12081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Avizit D, et al. Genome of Tenualosa ilisha from the river Padma, Bangladesh. BMC Res. Notes. 2018;11:921. doi: 10.1186/s13104-018-4028-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mollah MBR, Khan MGQ, Islam MS, Alam MS. First draft genome assembly and identification of SNPs from hilsa shad (Tenualosa ilisha) of the Bay of Bengal [version 1; peer review: 1 approved] F1000 Res. 2019;8:320. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.18325.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jones FC, et al. The genomic basis of adaptive evolution in threespine sticklebacks. Nature. 2012;484:55–61. doi: 10.1038/nature10944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Amemiya CT, et al. The African coelacanth genome provides insights into tetrapod evolution. Nature. 2013;496:311–316. doi: 10.1038/nature12027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yuan Z, et al. Comparative genome analysis of 52 fish species suggests differential associations of repetitive elements with their living aquatic environments. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:141. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-4516-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gialluisi A, et al. Genome-wide association scan identifies new variants associated with a cognitive predictor of dyslexia. Translational Psychiatry. 2019;9:77. doi: 10.1038/s41398-019-0402-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.The FC, the RP, Clst. A promoter-level mammalian expression atlas. Nature, 507:462 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Lodish, H., Berk, A. & Zipursky, S. L. Molecular cells Biology. 4th edition. New York: W.H. Freeman, Section 22.1, Cell to cell adhesion and communication (2000).

- 54.Bharadwaj R, Cunningham KM, Zhang K, Lloyd TE. Figure 4 regulates lysosome membrane homeostasis independent of phosphatase function. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2015;25:681–692. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddv505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gay CM, Zygmunt T, Torres-Vázquez J. Diverse functions for the semaphorin receptor PlexinD1 in development and disease. Dev. Biol. 2010;349:1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Riccardi D, Brown EM. Physiology and pathophysiology of the calcium-sensing receptor in the kidney. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2009;298:F485–F499. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00608.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Clements CS, et al. The crystal structure of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein, a key autoantigen in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11059–64. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1833158100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Günzel D, Yu AS. Claudins and the modulation of tight junction permeability. Physiol. Rev. 2013;93:525–569. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00019.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kraev A, et al. Molecular cloning of a third member of the potassium-dependent sodium-calcium exchanger gene family, NCKX3. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:23161–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102314200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cao Q, et al. Physiological mechanism of osmoregulatory adaptation in anguillid eels. Fish physiology and biochemistry. 2018;44(2):423–433. doi: 10.1007/s10695-018-0464-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pinto PI, et al. Gill transcriptome response to changes in environmental calcium in the green spotted puffer fish. BMC genomics. 2010;11:476. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ferreira M, Costa J, Reis-Henriques MA. ABC transporters in fish species: a review. Front. Physiol. 2014;5:266. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takahashi K, et al. ABC proteins: key molecules for lipid homeostasis. Med Mol Morphol. 2005;38:2–12. doi: 10.1007/s00795-004-0278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leguen I, Le CA, Montfort J, Peron S, Fautrel A. Transcriptomic analysis of Trout gill tonocytes in fresh water and sea water using Laser Capture Microdissection combined with Microarray Analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(10):e0139938. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0139938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Data for this paper were retrieved from the Zebrafish Information Network (ZFIN), University of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403-5274; URL, http://zfin.org/; available at, https://zfin.org/ZDB-GENE-040426-3. [27th August, 2019].

- 66.Li L, et al. Expression and activity of V-H+-ATPase in gill and kidney of marbled eel Anguilla marmorata in response to salinity challenge. J Fish Biol. 2015;87:28–42. doi: 10.1111/jfb.12687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fiol DF, Kültz D. Osmotic stress sensing and signaling in fishes. FEBS J. 2007;274:5790–5798. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Manzon LA. The role of prolactin in fish osmoregulation: a review. Gen Comp Endocr. 2002;125(2):291–310. doi: 10.1006/gcen.2001.7746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rossier BC. Osmoregulation during Long-Term Fasting in Lungfish and Elephant Seal: Old and New Lessons for the Nephrologist. Nephron. 2016;134:5–9. doi: 10.1159/000444307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tingaud-Sequeira A, et al. Structural and functional divergence of two fish aquaporin-1 water channels following teleost-specific gene duplication. BMC Evol. Biol. 2008;8:259. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Tipsmark CK, Sørensen KJ, Hulgard K, Madsen SS. Claudin-15 and -25b expression in the intestinal tract of Atlantic salmon in response to seawater acclimation, smoltification and hormone treatment. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 2010;155:361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Verri, T. et al. The SoLute Carrier (SLC) Family Series in Teleost Fish. Chapter 10. Book Editor(s): Marco Saroglia, Zhanjiang (John) Liu. Functional Genomics in Aquaculture (2012).

- 73.Paillart C, Winkfein RJ, Schnetkamp PP, Korenbrot JI. Functional Characterization and Molecular Cloning of the K+-dependent Na+/Ca2+Exchanger in Intact Retinal Cone Photoreceptors. J. Gen. Physiol. 2007;129:1–16. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Altimimi HF, Schnetkamp PP. Na+/Ca2+-K+ exchangers (NCKX): functional properties and physiological roles. Channels (Austin) 2007;1:62–69. doi: 10.4161/chan.4366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cai X, Lytton J. Molecular cloning of a sixth member of the K+-dependent Na+/Ca2+ exchanger gene family, NCKX6. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5867–76. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310908200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang X, et al. RNA-Seq analysis of salinity stress– responsive transcriptome in the liver of spotted sea bass (Lateolabrax maculatus) PLoS ONE. 2017;12(3):e0173238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nakada T, et al. Roles of Slc13a1 and Slc26a1 sulfate transporters of eel kidney in sulfate homeostasis and osmoregulation in freshwater. Am J Physiol-Reg I. 2005;289:R575–R585. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00725.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Griffith MB. Toxicological perspective on the osmoregulation and ionoregulation physiology of major ions by freshwater animals: Teleost fish,crustacea, aquatic insects, and Mollusca. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2017;36:76–600. doi: 10.1002/etc.3676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Taugbøl A, Arntsen T, Ostbye K, Vøllestad LA. Small changes in gene expression of targeted osmoregulatory genes when exposing marine and freshwater threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) to abrupt salinity transfers. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106894. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lionetto MG, et al. Role of BK channels in the apoptotic volume decrease in native Eel intestinal cells. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2010;25:733–744. doi: 10.1159/000315093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Furukawa F, Watanabe S, Kimura S, Kaneko T. Potassium excretion through ROMK potassium channel expressed in gill mitochondrion-rich cells of Mozambique tilapia. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2012;302:R568–R5676. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00628.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Loncoman C, et al. Application of a real-time PCR assay to detect BK potassium channel expression in samples from Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) acclimated to freshwater. Arch. Med. Vet. 2015;47:215–220. doi: 10.4067/S0301-732X2015000200013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Loncomana CAJ, et al. Potassium channel mRNA level changes in gills of Atlantic salmon after brackish water transfer. Aquaculture. 2018;491:184–189. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lam SH, et al. Differential transcriptomic analyses revealed genes and signalling pathways involved in iono-osmoregulation and cellular remodelling in the gills of euryhaline Mozambique tilapia, Oreochromis mossambicus. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:921. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Marshall WS, et al. Claudin-10 isoform expression and cation selectivity change with salinity in salt-secreting epithelia of Fundulus heteroclitus. Journal of Experimental Biology. 2018;221:jeb168906. doi: 10.1242/jeb.168906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bagherie-Lachidan M, Wright SI, Kelly SP. Claudin-8 and -27 tight junction proteins in puffer fish Tetraodon nigroviridis acclimated to freshwater and seawater. Journal of Comparative Physiology B. 2009;179:419–31. doi: 10.1007/s00360-008-0326-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Tipsmark CK, Sørensen KJ, Madsen SS. Aquaporin expression dynamics in osmoregulatory tissues of Atlantic salmon during smoltification and seawater acclimation. J Exp Biol. 2010;213:368–379. doi: 10.1242/jeb.034785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bui P, Kelly SP. Claudin-6, -10d and -10e contribute to seawater acclimation in the euryhaline puffer fish Tetraodon nigroviridis. J Exp Biol. 2014;15:1758–67. doi: 10.1242/jeb.099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reilly SC, Quinn JP, Cossins AR, Sneddon LU. Novel candidate genes identified in the brain during nociception in common carp (Cyprinus carpio) and rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Neuroscience Letters. 2008;437:135–138. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.03.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Watanabe M. Gap junction in the teleost fish lineage: Duplicated connexins may contribute to skin pattern formation and body shape determination. Front. Cell Dev. Bio. 2017;5:13. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2017.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hebert C, Stains JP. An intact connexion 43 is required to enhance signalling and gene expression in osteoblast–like cells. J. Cell. Biochem. 2013;114:2542–2550. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eastman SD, Chen TH, Falk MM, Mendelson TC, Iovine MK. Phylogenetic analysis of three complete gap junction gene families reveals lineage-specific duplications and highly supported gene classes. Genomics. 2006;87:265–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Carette D, et al. Connexin 33 impairs gap junction functionality by accelerating connexin 43 gap junction plaque endocytosis. Traffic. 2009;10:1272–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00949.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Whitehead A, Galvez F, Zhang S, Williams LM, Oleksiak MF. Functional Genomics of Physiological Plasticity and Local Adaptation in Killifish. Journal of Heredity. 2011;102:499–511. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esq077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Tseng YC, Hwang PP. Some insights into energy metabolism for osmoregulation in fish. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2008;148:419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2008.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Sangiao-Alvarellos S, et al. Time course of osmoregulatory and metabolic changes during osmotic acclimation in Sparus auratus. J. Exp. Bio. 2005;208:4291–4304. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Martos-Sitcha JA, et al. Unraveling the tissue-specific gene signatures of gilthead Sea Bream (Sparus aurata L.) after hyper- and hypo-osmotic challenges. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0148113. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw PacBio reads are available through the Short Read Archive (SRA) database (SRP126802) of NCBI under Bioproject (PRJNA422030) and Bio-Sample (SAMN08162886). This Whole Genome Shotgun project has been deposited at DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under the accession PYXC00000000. The version described in this paper is version PYXC01000000, includes primary and alternate contigs. The raw sequence reads from Illumina sequencing were submitted to NCBI, SRA database (SRR 6384292, SRR6384293 and SRR6384294) under Bioproject (PRJNA422030) and Bio-Sample (SAMN08195513). The raw iso-seq reads of PacBio RSII were submitted to SRA database under Bioproject (PRJNA417747). SRA and BioSample Accessions were provided in Table S5.