Abstract

Background/Objectives

Many older adults receive unnecessary screening colonoscopies. We previously conducted a survey using a national online panel to assess older adults’ preferences for how clinicians can discuss stopping screening colonoscopies. We sought to assess the generalizability of those results by comparing them to a sample of older adults with low health literacy.

Design

Cross-sectional survey.

Setting

Baltimore metropolitan area (low health literacy sample) and a national, probability-based online panel—KnowledgePanel (national sample).

Participants

Adults 65+ with low health literacy measured using a single-question screen (low health literacy sample, n = 113) and KnowledgePanel members 65+ who completed survey about colorectal cancer screening (national sample, n = 441).

Measurements

The same survey was administered to both groups. Using the best-worst scaling method, we assessed relative preferences for 13 different ways to explain stopping screening colonoscopies. We used conditional logistic regression to quantify the relative preference for each explanation, where a higher preference weight indicates stronger preference. We analyzed each sample separately, then compared the two samples using Spearman’s correlation coefficient, the likelihood ratio test to assess for overall differences between the two sets of preference weights, and the Wald test to assess differences in preference weights for each individual phrases.

Results

The responses from the two samples were highly correlated (Spearman’s coefficient 0.92, p < 0.0001). The most preferred phrase to explain stopping screening colonoscopy was “Your other health issues should take priority” in both groups. The three least preferred options were also the same for both groups, with the least preferred being “The doctor does not give an explanation.” The explanation that referred to “quality of life” was more preferred by the low health literacy group whereas explanations that mentioned “unlikely to benefit” and “high risk for harms” were more preferred by the national survey group (all p < 0.001).

Conclusion

Among two different populations of older adults with different health literacy levels, the preferred strategies for clinicians to discuss stopping screening colonoscopies were highly correlated. Our results can inform effective communication about stopping screening colonoscopies in older adults across different health literacy levels.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-019-05258-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: cancer screening, communication, colorectal cancer, health literacy, patient preferences

INTRODUCTION

Screening colonoscopy is an effective way of reducing colorectal cancer deaths, but the benefit is delayed for many years while significant harms, such as complications from the colonoscopy (bleeding, infection, perforations, anesthesia risk) and over-treatment of clinically unimportant cancers, can occur in the short term and the risk of these harms increases with age.1–6 Clinical practice guidelines recommend against routine colorectal cancer screening when the potential harms of screening outweigh its benefits.6–8 However, many older adults who meet age criteria (often defined as > 75 years old) and/or life expectancy criteria (often defined as < 10 years of life expectancy) for stopping routine screening continue to be screened for colorectal cancer. 9–11 One national study showed that colorectal cancer screening rate was 51% among adults 65+ years with life expectancy < 10 years.10

One contributor to excessive screening is that clinicians are uncomfortable discussing stopping cancer screening with patients.12–14 Because best practices for discussing cancer screening cessation are largely undefined, we explored, in our prior work, older adults’ preferred communication strategies for clinicians to discuss stopping cancer screening.15 We found that older adults most preferred their clinicians to describe stopping cancer screening in relation to “focusing on other health priorities” while discussing discomfort or inconvenience of the screening test, life expectancy, or not bring up a discussion were viewed more negatively.15 The main limitation of this prior work was that it relied on an existing online survey panel. Although the panel is nationally representative in demographic composition, the panelists tend to have high health literacy which may be an important determinant of the way patients would like to receive information about stopping cancer screening.

Health literacy, defined as the degree to which individuals have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand health information and services needed to make appropriate health decisions,16 is directly relevant to how one may prefer to receive health communications. Low health literacy has been associated with poorer knowledge and understanding of disease and greater difficulties participating in shared decision-making.17, 18 Here, we aimed to extend our prior work by assessing, first, how older adults with low health literacy prefer to receive information about colorectal cancer screening cessation and, second, to compare these findings to those from the national sample.

METHODS

Study Design and Sample

Low Health Literacy Sample

Older adults 65 years and older with low health literacy were recruited from the Baltimore metropolitan area through in-person recruitment and fliers at senior centers, assisted living communities, and community outreach events, referrals from other participants, and phone recruitment within a research registry maintained by the Johns Hopkins Older Americans Independent Center. We used a one-question validated screen for low health literacy—“how confident are you in filling out medical forms by yourself?”19 Individuals who answered “somewhat,” “a little bit,” or “not at all” were considered to have low health literacy. Participants with cognitive impairment, defined as missing 2 or more points on a validated six-question cognitive screen,20 were excluded.

National Survey Sample

Details about the national survey have been previously described.15 Older adults 65 years and older and English-speaking were recruited from KnowledgePanel, a probability-based online panel designed to be representative of US adults living in households.21 Panel members are recruited by random digit dialing and address-based sampling.21 Households without computers or Internet access are provided with both.21

This project was approved by a Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

Survey Instrument

The survey module examined communication around stopping cancer screening. All participants in the low health literacy sample answered questions about colorectal cancer screening and completed the survey on paper administered in person by a research team member. Participants in the national sample completed the survey online and were randomized to questions about colorectal cancer screening or prostate/breast cancer screenings. In this project, we focus only on those participants who answered questions about colorectal cancer screening.

The module content was identical for both groups. It briefly described the benefits and harms of screening colonoscopies, stated that sometimes it may be not appropriate for a person to get screening colonoscopies, and asked how doctors can better explain why a person should not get another screening colonoscopy.

To test the preference for different phrases that explain why screening colonoscopies may not be recommended, we employed a stated-preference method called best-worst scaling (BWS). BWS is a technique in which participants are presented with a list of objects and asked to choose the one object that they consider the best (most preferred) and the one object that they consider the worst (least preferred).22–24 This allows for comparison of relative values across objects, something that is not possible with traditional Likert scale surveys.22–24 As part of this technique, a subset of all objects is presented at a given time in a choice task and the participant completes a series of choice tasks where the objects in each task are systematically varied.

We identified the objects or the phrases to be tested in the survey using results from our previous qualitative interviews with older adults and with primary care physicians25, 26 and literature review.27–31 We included a total of 13 different phrases (Table 1) that mentioned guidelines, patient factors, screening-related benefits/harms, and two options of either making a recommendation to stop cancer screening without explanation or not bringing up cancer screening for discussion. We used a balanced incomplete block design to construct 13 choice tasks, each displaying 4 of the 13 phrases.32 At the end of choice tasks, we asked if the questions were “easy to understand,” “easy to answer,” and whether the answers “showed their real preferences.” Additional details about the survey are included in the Appendix in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

Table 1.

The 13 Phrases Tested in the Survey for Explaining Why Routine Screening Colonoscopy Is Not Recommended

| Explanation | Phrase |

|---|---|

| Other health priorities | Your other health issues should take priority. |

| Guidelines | Colonoscopy is not recommended for you by medical guidelines. |

| Unlikely to benefit | You are unlikely to benefit from the colonoscopy. |

| Age | We usually stop doing colonoscopies at your age. |

| At risk for harms | You are at high risk for harms from the colonoscopy. |

| Quality of life | We should focus on quality of life instead of looking for cancer. |

| Downstream tests | The colonoscopy can lead to unnecessary tests or treatments. |

| Would not help live longer | The colonoscopy would not help you live longer. |

| Discomfort | The colonoscopy can be very uncomfortable. |

| Inconvenience | The colonoscopy can be very inconvenient to complete. |

| No discussion | The doctor does not mention colonoscopy.* |

| May not live long enough | You may not live long enough to benefit from the colonoscopy. |

| No explanation | The doctor does not give an explanation.† |

*At the beginning of the choice tasks, additional description was given that stated: “Sometimes, if the doctor does not think a person needs a screening colonoscopy, the doctor may not mention colon cancer screening at all”

†At the beginning of the choice tasks, additional description was given that stated: “The doctor may tell a person that he does not need a colonoscopy without giving a reason”

We collected information about age, sex, race, ethnicity, and education from the low health literacy group. Demographic information was already known about KnowledgePanel members including age, sex, race/ethnicity, education, geographic region, and household income. From both groups, we collected information on cancer screening history, cancer screening attitude,29 health literacy,19 numeracy,33 self-reported health and functional status that were used to estimate life expectancy using a validated index,34 and decision-making preferences.35 We also asked if the participants’ regular doctors have recommended that they stop colonoscopies. We pilot tested the survey instrument with ten older adults who were not included in the study and iteratively revised the instrument based on their feedback.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected from low health literacy older adults from September 2016 to March 2017. Out of 382 older adults who expressed interest, 113 met eligibility criteria and completed the survey. The 269 who did not participate included 257 who did not meet eligibility criteria (including 233 who did not meet eligibility criteria for low health literacy) and 12 who later declined to participate. Eligible KnowledgePanel members (N = 1272) were invited to participate via email in November 2016. Among these, 881 (69.3%) completed the online survey; 441 were randomized to questions about colorectal cancer screening while the rest were randomized to questions about prostate/breast cancer screenings. Survey weights were applied to adjust for nonresponse in the national survey sample.

Participant characteristics were analyzed descriptively. BWS responses were analyzed using effects-coded conditional logistic regression models where the model coefficients, or preference weights, are a measure of relative preference.36 A more positive preference weight indicates that a phrase is more preferred relative to the other phrases, whereas a more negative preference weight indicates that the phrase is less preferred.36 We analyzed each sample separately. We then compared the two samples in several ways. First, we compared the two groups’ preference weights for each of the phrases using Spearman’s correlation coefficient. Second, we assessed overall differences between the two sets of preference weights using the likelihood ratio test. Third, we used a Swait-Louviere plot to assess whether there was systematic differences in scale (i.e., variance) between the two groups.37 When a difference in scale was found, we estimated a scale parameter using heteroskedastic conditional logistic regression, adjusted for scale between the two groups by multiplying one group’s regression coefficients by the scale parameter (a constant),37 and repeated the likelihood ratio test after adjusting for scale. We used Wald tests to assess differences in the preference weights for each individual phrases. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 14.

RESULTS

Our analysis included 113 participants in the low health literacy sample and 441 participants in the national survey sample who answered questions about colorectal cancer screening (Table 2). Using a single-question screen,19 56 (14%) of the national survey sample and all of the low health literacy sample had low health literacy. The low health literacy sample included higher proportion of women (76.1% vs 55.3%), higher proportion of blacks (53.1% versus 8.6%), higher average age (76.3 versus 73.8), and lower education. The low health literacy sample had more participants with < 10-year predicted life expectancy. The two groups were not different in their prior history of colonoscopy.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Characteristic | Low health literacy sample (n = 113) | National survey sample (n = 441) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 76.3 (7.5) | 73.8 (6.4) | 0.001 |

| Female sex | 86 (76.1%) | 232 (55.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Race | |||

| White, non-Hispanic | 47 (41.6%) | 292 (77.4%) | < 0.001 |

| African American, non-Hispanic | 60 (53.1%) | 108 (8.6%) | |

| Hispanic | / | 21 (7.7%) | |

| Other | 6 (5.3%) | 20 (6.3%) | |

| Has ever had a colonoscopy | 94 (83.2%) | 365 (81.2%) | 0.62 |

| Has had an up-to-date colonoscopy† | 77 (68.1%) | 323 (69.3%) | 0.81 |

| Physician have recommended stopping colonoscopy | 6 (5.3%) | 41 (11.1%) | 0.07 |

| Estimated life expectancy‡ | |||

| > 10 years | 50 (44.2%) | 319 (68.8%) | < 0.001 |

| 4–10 years | 49 (43.4%) | 97 (30.1%) | |

| < 4 years | 14 (12.4%) | 4 (1.1%) | |

| Educational level | |||

| Did not complete high school | 37 (32.7%) | 30 (13.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Completed high school | 43 (38.1%) | 144 (35.1%) | |

| < 4 year college | 24 (21.2%) | 115 (23.6%) | |

| College graduate or post-graduate degrees | 9 (8.0%) | 152 (27.5%) | |

| Low health literacy§ | 113 (100%) | 56 (14.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Numeracy33 (possible range 3–18) | 11.2 (4.1) | 14.0 (3.4) | < 0.001 |

| Decision-making preferences35 | |||

| Make own decisions | 35 (31.0%) | 259 (63.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Make decisions together | 75 (66.4%) | 175 (36.2%) | |

| Leave decision to doctor | 3 (2.7%) | 3 (0.5%) | |

| Screening attitude: “I plan to get screened for colorectal cancer for as long as I live.”29 | |||

| Strongly agree | 13 (11.5%) | 34 (5.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Somewhat agree | 56 (49.6%) | 112 (25.2%) | |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 13 (11.5%) | 139 (30.2%) | |

| Somewhat disagree | 26 (23.0%) | 102 (25.1%) | |

| Strongly disagree | 4 (3.5%) | 46 (13.5%) | |

| Not applicable due to history of cancer | 1 (0.9%) | 5 (0.7%) | |

Means and percentages are weighted for the national survey

†Up-to-date colonoscopy was defined to be within 10 years

‡Using the mortality risk index developed by Cruz et al.,34 a median life expectancy of > 10 years is defined as a < 50% mortality risk over 10 years; a median life expectancy between 4 and 10 years is defined as a > 50% mortality risk over 10 years and a < 50% mortality risk over 4 years; a median life expectancy of < 4 years is defined as a > 50% mortality risk over 4 years34

§We used a one-question validated screen for low health literacy—“how confident are you in filling out medical forms by yourself?”19 Individuals who answered “somewhat,” “a little bit,” or “not at all” were considered to have low health literacy

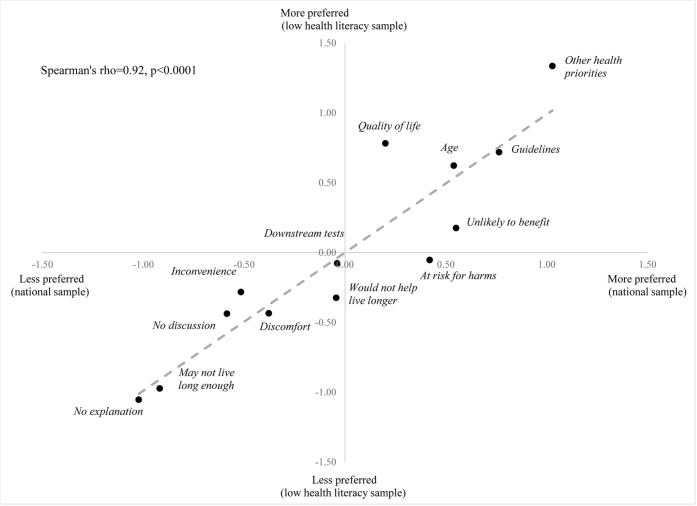

The relative preferences for the 13 phrases to discuss stopping screening colonoscopies are depicted in Fig. 1. The responses from the two samples were highly correlated (Spearman’s coefficient 0.92, p < 0.0001). The most preferred phrases to explain stopping screening colonoscopy for both groups were the same—“Your other health issues should take priority” (Table 3). The three least preferred options were also the same for both groups. The least preferred was “The doctor does not give an explanation,” the second least preferred was “You may not live long enough to benefit from colonoscopy,” and the third least preferred was “The doctor does not mention colonoscopy.”

Fig. 1.

Scatter plot of the preference weights for each phrase among the two sample groups. The x-axis shows the preference weights for the national survey sample and the y-axis shows the preference weights for the low health literacy sample. **Preference weights are the coefficients from conditional logistic regression models. Higher preference weight indicates stronger preference; low health literacy sample is adjusted to account for scale differences (k = 1.52).

Table 3.

Comparison of Conditional Logistic Regression Results Showing the Preference Weights for the 13 Phrases Among the Two Samples

| Explanation | Low health literacy sample | National survey sample | p value‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preference weight* | SE† | Rank | Preference weight | SE | Rank | ||

| Other health priorities | 1.33 | 0.12 | 1 | 1.03 | 0.04 | 1 | 0.01 |

| Guidelines | 0.72 | 0.11 | 3 | 0.76 | 0.04 | 2 | 0.71 |

| Unlikely to benefit | 0.18 | 0.11 | 5 | 0.55 | 0.04 | 3 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 0.62 | 0.12 | 4 | 0.54 | 0.04 | 4 | 0.51 |

| At risk for harms | − 0.05 | 0.11 | 6 | 0.42 | 0.04 | 5 | < 0.001 |

| Quality of life | 0.78 | 0.12 | 2 | 0.20 | 0.04 | 6 | < 0.001 |

| Downstream tests | − 0.08 | 0.11 | 7 | − 0.04 | 0.04 | 7 | 0.75 |

| Would not help live longer | − 0.32 | 0.12 | 9 | − 0.04 | 0.04 | 8 | 0.02 |

| Discomfort | − 0.43 | 0.11 | 10 | − 0.38 | 0.04 | 9 | 0.63 |

| Inconvenience | − 0.28 | 0.11 | 8 | − 0.52 | 0.04 | 10 | 0.05 |

| No discussion | − 0.44 | 0.11 | 11 | − 0.59 | 0.04 | 11 | 0.12 |

| May not live long enough | − 0.97 | 0.12 | 12 | − 0.92 | 0.04 | 12 | 0.67 |

| No explanation | − 1.05 | 0.11 | 13 | − 1.02 | 0.04 | 13 | 0.81 |

*Preference weights are the coefficients from conditional logistic regression models. Higher preference weight indicates stronger preference; low health literacy sample is adjusted to account for scale differences (k = 1.52)

†SE standard error

‡Using Wald test, we compared the preference weights for each individual phrase

Results of the Swait-Louviere plot and heteroscedastic conditional logistic modeling suggested that there was differences in scale, indicating that there was higher variance among the low health literacy participants’ responses by a scale factor of 1.52. After adjusting for this higher variance, the likelihood ratio test still showed differences between the two groups (p < 0.001) although the high degree of correlation as measured by the Spearman’s coefficient was unchanged (coefficient 0.92, p < 0.0001). The groups differed in responses to 6 phrases (Table 3). Although both groups’ most preferred explanation was referring to “other health priorities,” this was more strongly preferred in the low health literacy sample (p = 0.01). The explanation that “we should focus on quality of life instead of looking for cancer” was more preferred by the low health literacy group, whereas the explanations that mention “unlikely to benefit” and “high risk for harms” were more preferred by the national survey group (all three p < 0.001). The explanation that “the colonoscopy would not help you live longer” was not preferred by either group but more strongly disliked by the low health literacy group (p = 0.02). The explanation that the colonoscopy is “inconvenient to complete” was also not preferred by either group but more strongly disliked by the national survey group (p = 0.05). Sensitivity analysis comparing the low health literacy sample and only those with adequate health literacy in the national sample did not result in significant changes of results.

DISCUSSION

Having previously examined older adults’ preferences in this area using a national online panel with participants who had high health literacy,15 we specifically targeted older adults with low health literacy in this study to assess the generalizability of the previous results. We recruited a sample of older adults who not only had low health literacy but were also significantly different from the national online panel in age, gender, race, health status, and decision-making preferences. Despite all these differences, we found the two groups’ preferences for how clinicians should discuss stopping colorectal cancer screening to be highly correlated. The most preferred and the least preferred phrases were the same for both groups. This finding reassuringly addressed the limitation from the previous national study—whether this result is applicable to different populations.

For both samples, the most preferred explanation for stopping screening colonoscopies was to mention a priority shift to focus on other health issues. This is consistent with our previous findings where older adults mentioned that it would be helpful for clinicians to discuss what alternative health issues would be focused on instead of cancer screening so as to not feel like they were receiving less care.26 It also corresponds with our prior study of primary care clinicians where clinicians reported using this strategy when recommending stopping cancer screening.25

Compared to the national sample, mentioning quality of life was more preferred among older adults with low health literacy and mentioning the lack of benefits and the risk of harms of the colonoscopy was less preferred. Studies have shown that health literacy is not associated with quality of life. 38, 39 Studies do show that low health literacy is associated with lower knowledge in a number of diseases,17, 40 which often include understanding the associated benefits and harms. The underlying reasons for this difference needs to be examined further; in particular, the assessment of cognitive and affective responses (e.g., fear) to the information may be important.41 Our results suggest that framing discussion around quality of life may be more appealing than framing around the benefits and harms of screening when discussing stopping routine cancer screening with older adults with lower health literacy. Examples of possible discussion scripts are included in the Appendix in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

Mentioning guidelines was preferred in both samples to explain stopping screening colonoscopies. A systematic review of patient attitudes towards clinical practice guidelines found mixed attitudes but showed that, in several studies, patients perceived guidelines as a way to ensure high-quality care.42 Our finding demonstrates positive response among older adults, including those with low health literacy, to referencing guidelines as the reason to stop routine cancer screening.

Mentioning that cancer screening was not recommended based on older age was rated highly as well. There has been increasing attention to ageism and its role in healthcare inequity.43 Although prior literature suggests that older age is one of the reasons for older adults to consider stopping cancer screening,26, 27, 29, 30 whether older adults preferred to have their age explicitly stated as the reason to stop cancer screening has not been well-studied. A recent survey of a younger population of veterans (83.2% < 70 years old and 94.2% male) found that 49.3% of the participants did not think age should be used to decide when to stop screening.44 The participants from both samples in our study were older and included higher proportion of females, which may have contributed to the differences in findings. Additional studies are needed to examine the applicability of our results in different demographic populations.

Explanations that discussed life expectancy ranked low in both samples. In our previous qualitative work, the phrase “this test would not help you live longer” was more preferred over “you may not live long enough to benefit from this test.” In this study, we found that the first phrase was still more preferred than the second but even the first phrase, when tested against other explanations for screening cessation, was ranked relatively low. As clinical practice guidelines have increasingly advocated using life expectancy to inform cancer screening and other preventive care decisions,7, 8, 45–49 our finding highlights the importance of communicating these guideline recommendations in language that resonates with patients.

Our previous work found that some clinicians and older adults preferred to simply omit discussion about cancer screening as a way to stop screening.25, 26 The Shared Decision-Making workgroup of the USPSTF recommends that for preventive services with no benefit or net harm, such as those with a USPSTF “D” recommendation, the clinician has no obligation to initiate discussion.50 Our study finds that in two distinct samples, older adults found this to be one of the least preferred approaches. This finding raises an interesting ethical dilemma whether an opportunity to discuss stopping cancer screening should be at least offered by clinicians, recognizing that such discussion may lead to unnecessary screening and be burdensome in busy clinical encounters.

From a methodological standpoint, it was interesting that for this specific survey, we found highly correlated results despite very different recruitment and survey administration approaches. Although assessing the comparability of different sampling strategies was not our goal, our approach of administering the same survey to a separate sample using different recruitment method offers one way to help triangulate results from online surveys, which has become increasingly popular in research.

Our study has several limitations. First, the survey used hypothetical scenarios and responses may not reflect actual behaviors. In particular, the scenarios may not capture the rich dynamic and relationship between clinicians and patients. Second, we did not assess participants’ understanding of the benefits and harms of colonoscopy which may have impacted their responses. Third, the phrases that were tested were fairly short but actual discussions in clinical encounters are likely to be lengthier and touch upon more than one reason for stopping screening colonoscopies. Fourth, the format of best-worst scaling may be unfamiliar to participants, leading to inaccurate responses. However, only < 5% of the participants in the national group and < 3% of the low health literacy group disagreed with the statement “the answers showed my real preferences.” Fifth, we administered the same survey instrument with identical phrasing to both groups in order to compare the groups’ responses but some phrases may have been challenging for older adults with low health literacy. Lastly, we were not able to assess for response rate in the low health literacy group because it was a convenience sample. We intended to compare and contrast the results with the online survey findings and consider it a strength to have recruited two very different populations whose preferences were then found to be highly correlated. Because the two samples were different on a number of characteristics and we did not a priori plan subgroup analyses, we were not able to comment on the effect of any specific characteristic on the results.

In summary, we found that among two samples of older adults with different health literacy levels, the preferred messaging approaches for clinicians to discuss stopping screening colonoscopies were highly correlated. Framing screening cessation around a shift in health priorities and guideline recommendations may be attractive discussion strategies regardless of patients’ health literacy status. In older adults with limited health literacy, focusing the discussion around quality of life may be more preferred than focusing on benefits and harms of screening. Our results can directly inform clinical practice and facilitate effective communication about stopping cancer screening with older adults across health literacy levels, with the ultimate goal to improve the care of older adults.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 20 kb)

Funding/Support

This project was made possible by the Maryland Cigarette Restitution Fund (PHPA-G2034) and the R03AG050912 grant from the National Institute on Aging. In addition, Dr. Schoenborn was supported by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR) which is funded in part by KL2TR001077 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a Cancer Control Career Development Award from the American Cancer Society (CCCDA-16-002-01), a T. Franklin Williams Scholarship Award (funding provided by Atlantic Philanthropies, Inc., the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine-Association of Specialty Professors, and the American Geriatrics Society), and a career development award from the National Institute on Aging (K76AG059984). Dr. Boyd was supported by 1K24AG056578 from the National Institute on Aging. Dr. Xue was supported by P30AG021334 from the National Institute on Aging.

The funding sources had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, and preparation of paper.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Lee SJ, Boscardin WJ, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Conell-Price J, O’Brien S, Walter LC. Time lag to benefit after screening for breast and colorectal cancer: Meta-analysis of survival data from the United States, Sweden, United Kingdom, and Denmark. BMJ. 2013;346:e8441. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e8441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: A framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2750–2756. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.21.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lansdorp-Vogelaar I, Gulati R, Mariotto AB, et al. Personalizing age of cancer screening cessation based on comorbid conditions: Model estimates of harms and benefits. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(2):104–112. doi: 10.7326/M13-2867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris RP, Wilt TJ, Qaseem A. High Value Care Task Force of the American College of Physicians. A value framework for cancer screening: Advice for high-value care from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(10):712–717. doi: 10.7326/M14-2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckstrom E, Feeny DH, Walter LC, Perdue LA, Whitlock EP. Individualizing cancer screening in older adults: A narrative review and framework for future research. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(2):292–298. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2227-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin JS, Piper MA, Perdue LA, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: updated evidence report and systematic review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2016;315(23):2576–94. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.3332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qaseem A, Denberg TD, Hopkins RH, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: a guidance statement from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(5):378–86. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-5-201203060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rex DK, Boland CR, Dominitz JA, et al. Colorectal cancer screening: recommendations for physicians and patients from the U.S. multi-society task force on colorectal cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(7):1016–1030. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royce TJ, Hendrix LH, Stokes WA, Allen IM, Chen RC. Cancer screening rates in individuals with different life expectancies. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(10):1558–65. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schonberg MA, Breslau ES, Hamel MB, Bellizzi KM, McCarthy EP. Colon cancer screening in U.S. adults aged 65 and older according to life expectancy and age. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(4):750–756. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Powell AA, Saini SD, Breitenstein MK, et al. Rates and correlates of potentially inappropriate colorectal cancer screening in the veterans health administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(6):732–741. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3163-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schonberg MA, Ramanan RA, McCarthy EP, Marcantonio ER. Decision making and counseling around mammography screening for women aged 80 or older. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(9):979–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pollack CE, Platz EA, Bhavsar NA, et al. Primary care providers’ perspectives on discontinuing prostate cancer screening. Cancer. 2012;118(22):5518–5524. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schoenborn NL, Bowman TL, Cayea D, Pollack CE, Feeser S, Boyd C. Primary care practitioners’ views on incorporating long-term prognosis in the care of older adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(5):671–8. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schoenborn NL, Janssen EM, Boyd CM, Bridges JFP, Wolff AC, Pollack CE. Preferred clinician communication about stopping cancer screening among older US adults: results from a national survey. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4(8):1126–1128. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. National action plan to improve health literacy. Washington (DC): Author; 2010. https://health.gov/communication/hlactionplan/pdf/Health_Literacy_Action_Plan.pdf Accessed June 24, 2019.

- 17.Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(12):1228–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yin HS, Dreyer BP, Vivar KL, MacFarland S, van Schaick L, Mendelsohn AL. Perceived barriers to care and attitudes towards shared decision-making among low socioeconomic status parents: role of health literacy. Acad Pediatr. 2012;12(2):117–24. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wallace LS, Rogers ES, Roskos SE, Holiday DB, Weiss BD. Brief report: screening items to identify patients with limited health literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):874–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00532.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Hui SL, Perkins AJ, Hendrie HC. Six-item screener to identify cognitive impairment among potential subjects for clinical research. Med Care. 2002;40(9):771–81. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200209000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.GfK. KnowledgePanel recruitment and sample survey methodologies. http://www.gfk.com/fileadmin/user_upload/dyna_content/US/documents/KnowledgePanel_Recruitment_Sample_Survey_Methodology.pdf, accessed June 24, 2019.

- 22.Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J. Best-worst scaling: What it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health Econ. 2007;26(1):171–189. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cheung KL, Wijnen BF, Hollin IL, et al. Using best-worst scaling to investigate preferences in health care. Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(12):1195–1209. doi: 10.1007/s40273-016-0429-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wittenberg E, Bharel M, Bridges JH, Ward Z, Weinreb L. Using best-worst scaling to understand patient priorities: a case example of papanicolaou tests for homeless women. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(4):359–64. doi: 10.1370/afm.1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schoenborn NL, Bowman TL, Cayea D, Boyd C, Feeser S, Pollack CE. Discussion strategies used by primary care clinicians when stopping cancer screening among older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(11):e221–e223. doi: 10.1111/jgs.14444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoenborn NL, Lee K, Pollack CE, et al. Older adults’ views and communication preferences around cancer screening cessation. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(8):1121–1128. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schonberg MA, McCarthy EP, York M, Davis RB, Marcantonio ER. Factors influencing elderly women’s mammography screening decisions: implications for counseling. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-7-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Torke AM, Schwartz PH, Holtz LR, Montz K, Sachs GA. Older adults and forgoing cancer screening: “i think it would be strange”. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(7):526–531. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.2903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lewis CL, Kistler CE, Amick HR, et al. Older adults’ attitudes about continuing cancer screening later in life: A pilot study interviewing residents of two continuing care communities. BMC Geriatr. 2006;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarasenko YN, Wackerbarth SB, Love MM, Joyce JM, Haist SA. Colorectal cancer screening: patients’ and physicians’ perspectives on decision-making factors. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(2):285–93. doi: 10.1007/s13187-010-0145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howard K, Salkeld GP, Patel MI, Mann GJ, Pignone MP. Men’s preferences and trade-offs for prostate cancer screening: a discrete choice experiment. Health Expect. 2015;18(6):3123–35. doi: 10.1111/hex.12301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Street D, Street AP. Combinatorics of experimental design. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNaughton CD, Cavanaugh KL, Kripalani S, Rothman RL, Wallston KA. Validation of a short, 3-item version of the subjective numeracy scale. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(8):932–936. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15581800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cruz M, Covinsky K, Widera EW, Stijacic-Cenzer I, Lee SJ. Predicting 10-year mortality for older adults. JAMA. 2013;309(9):874–876. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wolff JL, Boyd CM. A look at person- and family-centered care among older adults: results from a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1497–504. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3359-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hauber AB, Gonzalez JM, Groothuis-Oudshoom CG, et al. Statistical methods for the analysis of discrete choice experiments: a report of the ISPOR conjoint analysis good research practices task force. Value Health. 2016;19(4):300–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wright SJ, Vass CM, Sim G, Burton M, Fiebig DG, Payne K. Accounting for scale heterogeneity in healthcare-related discrete choice experiments when comparing stated preferences: a systematic review. Patient. 2018;11(5):475–488. doi: 10.1007/s40271-018-0304-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Couture EM, Chouinard MC, Fortin M, Hudon C. The relationship between health literacy and quality of life among frequent users of health care services: a cross-sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2017;15(1):137. doi: 10.1186/s12955-017-0716-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, Halpern DJ, Crotty K. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(2):97–107. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-2-201107190-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Al Sayah F, Majumdar SR, Williams B, Robertson S, Johnson JA. Health literacy and health outcomes in diabetes: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):444–52. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2241-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witte K. Fear control and danger control: a test of the extended parallel process model (EPPM) Commun Monogr. 1994;61(2):113–134. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Loudon K, Santesso N, Callaghan M, et al. Patient and public attitudes to and awareness of clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review with thematic and narrative syntheses. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:321. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kydd A, Fleming A. Ageism and age discrimination in health care: fact or fiction? A narrative review of the literature. Maturitas. 2015;81(4):432–8. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Piper MS, Maratt JK, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, et al. Patient attitudes toward individualized recommendations to stop low-value colorectal cancer screening. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(8):e185461. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Denberg TD, Owens DK, Shekelle P. Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Screening for prostate cancer: a guidance statement from the clinical guidelines committee of the American College Of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(10):761–769. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA guideline. J Uro. 2013;190(2):419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oeffinger KC, Fontham ET, Etzioni R, et al. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.American Diabetes Association Standards of medical care in diabetes-2017 abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diabetes. 2017;35(1):5–26. doi: 10.2337/cd16-0067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bibbins-Domingo K. US Preventive Services Task Force. Aspirin use for the primary prevention of cardiovascular disease and colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(12):836–45. doi: 10.7326/M16-0577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sheridan SL, Harris RP, Woolf SH, Shared decision-making workgroup of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Shared decision making about screening and chemoprevention: a suggested approach from the US Preventive Services Task Force. Am J Prev Med. 2004;26(1):56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 20 kb)