Abstract

Background

To enhance the acute care delivery system, a comprehensive understanding of the patient’s perspectives for seeking care in the emergency department (ED) versus primary care (PC) is necessary.

Methods

We conducted a qualitative metasynthesis on reasons patients seek care in the ED instead of PC. A comprehensive literature search in PubMed, CINAHL, Psych Info, and Web of Science was completed to identify qualitative studies relevant to the research question. Articles were critically appraised using the McMaster University Critical Review Form for Qualitative Studies. We excluded pediatric articles and nonqualitative and mixed-methods studies. The metasynthesis was completed with an interpretive approach using reciprocal translation analyses.

Results

Nine articles met criteria for inclusion. Eleven themes under four domains were identified. The first domain was acuity of condition that led to the ED visit. In this domain, themes included pain: “it’s urgent because it hurts,” and concern for severe illness. The second domain was barriers associated with PC, which included difficulty accessing PC when ill: “my doctor said he was booked up and he instructed me to go to the ED.” The third domain was related to multiple advantages associated with ED care: “my doctor cannot do X-rays and laboratory tests, while the ED has all the technical support.” In this domain, patients also identified 24/7 accessibility of the ED and no need for an immediate copay at the ED as advantageous. The fourth domain included fulfillment of medical needs. Themes in this domain included the alleviation of pain and the perceived expertise of the ED healthcare providers.

Conclusions

In this qualitative metasynthesis, reasons patients visit the ED over primary care included (1) urgency of the medical condition, (2) barriers to accessing primary care, (3) advantages of the ED, and (4) fulfillment of medical needs and quality of care in the ED.

KEY WORDS: primary care, healthcare delivery, access to care, qualitative research, metasynthesis, patient preferences, patient-centered care

INTRODUCTION

There are over 350 million visits for acute care annually in the USA,1 and the acute care delivery system is struggling to meet the timeliness of patient care needs.2 Evidence of difficulties with accessing acute care abound in both the medical and lay press literature, with stories of frustration with the healthcare delivery system, difficulties with primary care access, and visits to the emergency department (ED) for “nonurgent” conditions.2–7

While the delivery of acute care has been a central principle of primary care,1, 8 fewer than half acute care visits involve the patient’s PC physician.1 This may be due, in part, to the evolution in primary care, with the focus of primary care dramatically shifting with an increased emphasis toward provision of care related to aging, chronic disease management, and coordination of specialty care.1, 9–11 As a result, an increasing number of acute care visits occur in the ED.1 Unfortunately, ED visits are rising while the number of EDs is decreasing12 resulting in ED crowding, boarding, and ambulance diversion, thereby potentially further limiting patient access to acute care services and increasing the difficulties with successfully meeting public health needs.13, 14

The Institute of Medicine has recommended that healthcare be “safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable”.15 In order to develop patient-centered timely healthcare, a comprehensive understanding of the reasons patients choose a specific healthcare setting over another for acute care needs is indicated. The qualitative studies to evaluate reasons patient choose one setting over another for their acute care needs have primarily been at single centers and have involved small numbers of patients. Synthesizing data from multiple qualitative studies will provide beneficial insight into patient choices for acute care while simultaneously enhancing the transferability of the qualitative study findings.16, 17 Therefore, we critically evaluated and synthesized qualitative studies on reasons for seeking care in the ED instead of through primary care. The specific research question for this qualitative metasynthesis was “What are patients’ perspectives on reasons to seek healthcare services in the ED instead of through primary care?”

METHODS

Study Design

We conducted a qualitative metasynthesis grounded in social constructivist epistemology using an established framework for metasynthesis of qualitative data.17 We identified the research question, determined the nature and scope of the articles for inclusion in the study, conducted a standardized assessment of article quality, and performed a team-based inductive analysis to identify reciprocal themes. The process involved interpretations of the articles’ interpretations and a team-based integrative synthesis of the data.18, 19 Since the purpose of the investigation was to derive new knowledge from the existing studies, we followed the established metasynthesis approach of Noblit and Hare which indicates that qualitative studies about similar topics can be combined to obtain new, broader interpretive meaning.20

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

For the metasynthesis, we included published studies on adult (≥ 18 years of age) patients that mentioned accessing the ED instead of primary care and were indexed in a bibliographic database by December 2018. We excluded non-English articles, conference abstracts, surveys, mixed-methods studies, and systematic reviews.

Search Strategy

We searched to identify articles for inclusion in the metasynthesis using PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, and the Current Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL). The search was limited to articles published from 2000 to 2018. The following search terms were used to identify the most relevant articles for the qualitative metasynthesis: ED, emergency room, emergency, utilization, healthcare utilization, frequency, over-utilization, and primary care. The database searches were supplemented with review of reference lists of articles and review articles on the topics of ED and primary care utilization.

Two reviewers (J.V. and M.L.B.) independently performed the searches in a stepwise fashion. First, they examined each title for relevance to our study question. Second, among the articles potentially relevant to the study question, they examined the abstract of the article. Finally, if the article abstract demonstrated relevance to the study question, the entire article was assessed for inclusion in the metasynthesis. Both reviewers agreed upon the final set of articles included in the metasynthesis.

Methodological Critical Review

Articles meeting criteria for inclusion were critically appraised by three members of our research team: two emergency medicine physicians (J.A.V. and K.L.R.) and a master’s-level trained social worker (M.L.B.). Article quality was assessed using the McMaster Quality Assessment Guidelines—Qualitative Studies Critical Review Form 2.0.21 This critical appraisal tool was specifically developed to facilitate critical appraisal of qualitative research articles. The instrument includes assessments of key components and domains of qualitative research articles, including study purpose, review of background literature, study design, sampling, data collection, data analyses, and conclusions.21

Approach to the Metasynthesis

We used reciprocal translation analysis as our meta-synthetic approach. Each interdisciplinary research team member (J.A.V., K.L.R., and M.L.B.) independently reviewed all the articles and developed a list of themes and subthemes. Subsequently, we met to compare potential themes, using consensus to select the final themes and subthemes.

RESULTS

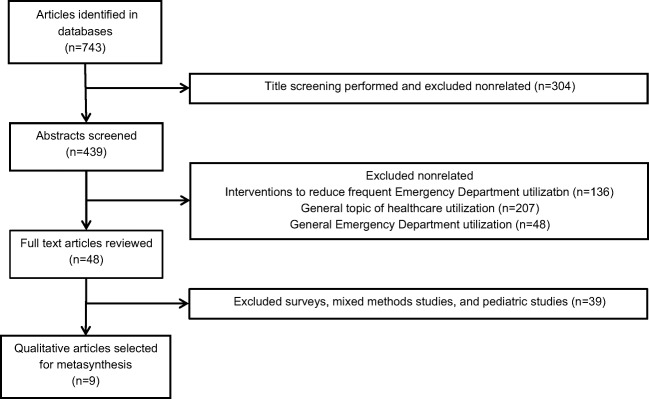

Our initial search of the literature produced 743 articles. We excluded articles that were mixed methods, were not qualitative studies, did not address the “patient” perspective on our research topic, and those that included data on pediatric (< 18 years of age) patients. After exclusions, nine articles met criteria for inclusion in our measynthesis.2, 22–29 The results of our search are outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Article selection process for the qualitative metasynthesis.

The final nine studies included in this metasynthesis were chosen by consensus after full article review: Durand,22 Howard,23 Hunter,24 Kangovi,25 Koziol-McLain,26 Lowthian,27 Rising,2 Schmeidhofer,28 and Shaw.29 The characteristics of the studies included are described in Table 1. Five of the included studies were conducted in the USA and the remaining four studies were conducted in Germany, France, Northwest England, and Australia. The sample size for the studies included in the metasynthesis ranged from 30 to 100 patients.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Studies Included in the Qualitative Metasynthesis

| Author | Year | Country | Study purpose | Study design | Methods | Participants | Summary of findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Durand A, et al. | 2006 | France | Explore reasons why people with nonurgent complaints choose to come to EDs and how ED health professionals perceive the phenomenon of “nonurgency” | Qualitative descriptive | Semistructured interviews in 10 EDs; inductive conventional content analysis | 87 patients, arriving by their own means, and triaged as nonurgent by triage nurse at 10 EDs |

Patient’s decisions to seek care in ED were linked with perceived healthcare needs and availability of healthcare resources. The provider perceptions were not included in the summary findings as the metasynthesis was focused on the patient’s reasons for choosing the ED for their healthcare. |

| Howard, MS et al. | 2003 | USA | Evaluate “why do people choose to come to the emergency department instead of their primary care provider with nonurgent medical complaints? | Qualitative descriptive | Interviews with exploration of the patients’ perception of the nonurgent ED visit | 31 patients with a PCP and recent nonurgent ED visit (as per standards of the Emergency Nursing Association) including rash without fever, rhinitis, cold symptoms, and cystitis | Themes identified in the study included the following: (1) patients instructed by PCP to use the ED, (2) patients unable to secure an appointment with PCP in a timely manner, and (3) overall availability of healthcare was an important factor; ED is most efficient and readily available and may expedite recovery to facilitate return to work. |

| Hunter C, et al. | 2013 | Northwest England | Explore how patients with long-term conditions choose between available healthcare options during a health crisis | Qualitative framework approach | A thematic framework was developed and honed through inductive, iterative process | 50 patients with one or more of four long-term conditions: coronary heart disease, asthma, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | Candidacy and recursivity play a role in choosing emergency care services. Candidacy describes how access to care is framed as requiring work for patients to achieve, and eligibility to assess care is continuously negotiated in patient–practitioner relationships. Recursivity describes how future demand for healthcare services and the process of help-seeking is determined by the patient’s previous experiences within the healthcare system. Patients rely on experiential knowledge of services and practitioners to choose between services and to establish their candidacy for accessing healthcare services. |

| Kangovi S, et al. | 2011 | USA | Determine the reasons for hospital care among low socioeconomic status patients | Qualitative study with modified grounded theory approach | Interviews with urban low socioeconomic status patients (determined by insurer and place of residence) to explore why they prefer hospital care | 40 uninsured and Medicaid patients residing in a region of Philadelphia with more than 30% residents living in poverty, at two hospitals | The benefits of hospital care relative to ambulatory care included better overall access across a variety of domains, and higher levels of trust in the technical quality of hospital providers and services (better able to diagnose and control problems particularly for any problem that may be diagnostically controversial) |

| Koziol-McLain J, et al. | 2000 | USA | Understand the context in which patients choose to seek healthcare in the emergency department | Exploratory descriptive research study with narrative descriptive approach | Interview with open-ended question, “Can you tell me the story, or the chain of events, that led to your coming to the emergency department today?” | 30 uninsured patients at an urban University Emergency Department triaged as nonurgent who were being discharged home | Themes for using the ED over primary care included toughing it out (suffering with dental pain for a long time and finally decided to seek care); symptoms overwhelming self-care measures (symptoms worsening despite attempting treatment with over the counter medications), calling a friend (called upon others to aid them during illness; mothers were contacted most frequently); and convenience (only able to come in evening and ongoing illness may impact ability to work). |

| Lowthian JA, et al. | 2011 | Australia | To examine nonclinical factors associated with emergency department attendance by lower urgency older adult patients | Exploratory descriptive study | Structured interviews analyzed using a qualitative thematic framework | 100 patients ≥ 70 years presenting to a tertiary public hospital ED with low urgency care needs (triage levels 3–5) | Two themes among older adults seeking emergency care services for lower urgency conditions: perceived access block to primary or specialist services, and expectation of more timely or specialized care in the ED. |

| Rising KL, et al. | 2016 | USA | To engage patients in exploration of how to reinvent components of the acute care delivery system to best meet their goals | Modified grounded theory | Semistructured interviews of patients being discharged from the ED with open-ended questions to prompt patient reflections on their primary drivers to the ED, expectations about this ED visit, and anticipated goals and needs for the days after their discharge | 40 participants with a history of diabetes mellitus or cardiovascular disease who were being discharged from the ED | Four themes were identified as drivers of patient visits to the ED: fear and uncertainty about medical concern; functional symptoms; mobility limitations; and PCP unable to meet care needs. |

| Schmiedhofer M, et al. | 2014–2015 | Germany | To explore motives of patients who visited the ED and whose conditions were categorized as low acuity | Qualitative content analysis | Semistructured interviews using a qualitative content analysis approach to identify patient motives for ED visits | 64 adult patients classified as Manchester Triage System 4 and 5, the lowest in terms of ED visit acuity | Two essential motives for seeking ED care for low acuity concerns were identified as follows: convenience and health anxiety, triggered by time constraints and focused usage of multidisciplinary medical care in a highly equipped setting. |

| Shaw EK, et al. | 2010 | USA | To determine patients’ decision-making processes to use the emergency department versus primary care alternatives | Grounded theory | Interviewed in an iterative fashion with ongoing analysis of interview data informing further interviews | Purposive sample of 30 patients, triaged to the nonurgent area of the ED |

Decision-making processes identified two subgroups within the study population as follows: • No knowledge of alternative primary care options: patients without PCP, referred by advertisement or known acquaintance; several indicated that without insurance thought ED was the only place to obtain care • Knowledge of alternatives: This was the majority of patients in the sample (n = 23). Chose ED for the following reasons: – Being instructed by a medical professional – Facing access barriers to their regular source of care – Perceived racial issues with PCP option – Defining their healthcare need as an emergency that required ED services – Transportation barriers to other PCP options – Factoring in costs to use other PCP options versus ED |

ED, emergency department; PCP, primary care physician

The results of the methodologic review for the study are outlined in Table 2. The metasynthesis produced four themes and several subthemes which are outlined in Table 3. The themes associated with patients choosing the ED over primary care included the following: acuity of condition, barriers to primary care, advantages of the ED, and quality of hospital-based care and fulfillment of healthcare needs. Each of these themes is described below.

Table 2.

Summary of Critical Review of Studies Included in Metasynthesis

| Durand | Howard | Hunter | Kangovi | Koziol-McLain | Lowthian | Rising | Schmeidhofer | Shaw | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study purpose | |||||||||

| Was the purpose and/or research question stated clearly? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Literature | |||||||||

| Was relevant background literature reviewed? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Study design | |||||||||

| What was the design? | Qualitative descriptive | Qualitative descriptive | Framework approach | Grounded theory | Narrative descriptive | Content analysis | Modified grounded theory | Content analysis | Grounded theory |

| Was a theoretical perspective identified? | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Methods used? | Interviews | Interviews | Interviews | Interviews | Interviews | Interviews | Interviews | Interviews | Interviews |

| Sampling | |||||||||

| Was the process of purposeful selection described? | No | No | Yes | Yes | Limited | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was sampling done until redundancy in data was reached? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not addressed | Not addressed | Not addressed | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Was informed consent obtained? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Data collection | |||||||||

| Descriptive clarity | |||||||||

| Clear and complete description of site? | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Clear and complete description of participants? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Limited | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Role of researcher and relationship with participants? | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Identification of assumptions and biases of researcher | No | Yes | Limited | Limited | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Procedural rigor was used in data collection strategies? | Yes, but details missing | Unclear | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Data analyses | |||||||||

| Analytical rigor | |||||||||

| Were data analyses inductive? | Yes | Not addressed | Yes | Yes | Not addressed | Not addressed | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Were findings consistent with reflective data? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Auditability | |||||||||

| Was a decision trail developed? | Not addressed | Not addressed | Not addressed | Yes | Not addressed | Not addressed | Yes | Not addressed | Not addressed |

| Was the process of analyzing the data described adequately? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Theoretical considerations | |||||||||

| Did a meaningful picture of the phenomenon under study emerge | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Overall rigor | |||||||||

| Credibility: Do the descriptions and interpretations of the participants appear to capture the phenomenon? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Limited | Yes | Yes | Limited |

| Transferability: Can the findings be transferred to other situations? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dependability: Was there consistency between the data and findings? | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Limited | Limited | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Confirmability: Were strategies employed to minimize bias? | Limited | No | No | Yes | No | Limited | Yes | Yes | Limited |

| Conclusions and implications | |||||||||

| Conclusions were appropriate given study findings? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Limited | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Findings contributed to theory development and future practice/research? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Table 3.

Team Synthesis and Reciprocal Translation for Qualitative Metasynthesis

| Derived analytic themes and subthemes | Article† | Primary study themes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Acuity of condition and illness requiring medical attention | ||

| Pain and discomfort are concerning | 1, 5, 7, 9 | To alleviate pain or discomfort |

| Fear regarding illness severity | 1, 3, 5, 7, 9 | Severity of symptoms causing concern for emergent medical condition |

| Anxiety regarding illness severity | 1, 5, 7, 9 | Seeking reassurance that illness is not severe |

| Necessary visit | 3, 5 | “Last resort” or need for help serious, I “had to” |

| 7, 9 | Tried waiting but symptoms overwhelming | |

| 3, 5 | Family members or healthcare professional confirmed need for emergency care | |

| 2. Barriers to access to primary care | ||

| Limited availability | 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 | Difficulty obtaining timely appointment when ill |

| 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9 | Limited availability in general of PCP | |

| 2, 4, 6 | Significant wait at PCP; “disrespectful” of patient’s time | |

| 2 | Unable to miss work while PCP appointment pending | |

| Limited access | 1, 2 | Unable to attend primary care weekends and evenings when having availability |

| Limited diagnostic and testing capabilities | 8 | PCP has limited ability to diagnose acute medical care conditions |

| Disease-specific care and testing unavailable | 3, 6 | Need specialist care which can be found in emergency department |

| 3, 6, 8 | Refer patients to the emergency department for acute diagnostic evaluations | |

| Referred by healthcare provider | 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9 | Referred to the ED for diagnostic evaluation and/or admission by PCP or another healthcare provider |

| 3. Advantages of the emergency department | ||

| Resource availability | 1, 6, 8 | Necessary laboratory and diagnostic testing available |

| 4 | Primary care is “just for checkups,” hospital if “you are sick or in pain at all” | |

| Convenience | 1, 6, 8 | Single-site care with necessary technical access and medications |

| 2 | Need to “get feeling better” to be able to return to work | |

| 1, 6 | No need to make multiple appointments in different places necessitating navigating organizational constraints | |

| Evaluation opportunities | 1, 2, 6, 8 | Diagnostic and testing modalities all readily available |

| Efficiency | 1, 2, 5, 6, 8 | Potential for testing and consultations at one site |

| Ease of access | 3, 5, 6, 8 | Capable of meeting patient care needs 24 h a day, 7 days a week |

| 3, 4, 5 | Transportation options (EMS or friends/family after hours) | |

| Work and financial limitations | 2, 7 | Due to financial considerations need immediate care and cannot miss additional work |

| Transportation opportunities to the emergency department | 3, 4, 5, 9 | Ambulance for ill health or friend/family transport when available after work hours |

| Childcare | 2, 5 | Opportunity for assistance with child care in the off hours to facilitate emergency department visit |

| Financial accessibility | 6, 9 | Difficulty with necessary copay for primary care access |

| 4, 6, 9 | Without insurance unable to access primary care but do have access to the Emergency Department | |

| 4. Quality of hospital-based care and fulfillment of healthcare needs/had good services/family said good | ||

| Fulfillment of healthcare needs | 1, 7 | Alleviating pain or discomfort and anxiety being caused by condition |

| 1, 7, 8 | Reassurance regarding medical condition | |

| 3 | Provide disease-specific care | |

| Technological expertise | 3, 4, 6, 8 | Advanced diagnostic services |

| Diagnostic expertise | 3, 4, 6, 8, 9 | Capable of identifying and treating the problem; trust in healthcare provider |

Theme 1: Acuity of Condition

Many individuals visited the ED based on the perceived acuity and urgency of the condition or illness requiring immediate medical attention. Visitors to the ED were specifically concerned about the severity of their illness or condition and the level of pain which may be associated with a serious medical condition. They reported, “It’s urgent because it hurts.”22 “I was afraid; I was concerned because I did not know if my problem was serious”.22 Patients reported difficulty ascertaining whether their concern was life-threatening; “I didn’t want to take a chance, because I’m no doctor. I’m no nurse. I’m just a patient”.2 Pain control was also a concern for ED visitors; “It’s just that painful, you’ve just got to go [to the hospital].”24 “So I jus’ been trying to bear with it. Then I just couldn’t handle it anymore, so I came in.”26 Within this theme, individuals also reported the desire for reassurance that everything was alright. “I do not know what I have, but it worried me, so I preferred to come immediately to the ED so at least I am reassured”.22 The theme of visiting the ED for acute conditions speaks to the understanding of the importance of the ED in the community as a critical link in the chain of healthcare provision in which healthcare providers are available to address emergent and urgent conditions and pain. There was a general awareness among ED visitors that the ED was the “place to go to” for help when faced with a serious of acute medical concern.

Theme 2: Barriers to Access to Primary Care

The second theme for the metasynthesis was barriers to accessing primary care. ED visitors indicated that primary care physicians had significantly limited availability thereby impacting their decision to visit the ED. Many ED visitors indicated that it is difficult to obtain a primary care physician appointment when ill. “I like him (speaking of her primary care physician) but it is impossible to see him if you are sick. It is weeks before you can get an appointment.”23 “Very very rare have I phoned up the doctor and been able to get in … to see my general practitioner within two or three days. It’s nearly always next week or the week after or whatever.. you need out the out of hours doctors really to help you out for them situations.”24 “The ED is quicker than getting an appointment with the general practitioner.”27 Many ED visitors indicated that the wait at their primary care physician’s office once they arrived for an appointment was prohibitive. “I feel like I sit for hours for him to see me for 2 minutes; it is much quicker to come out here.”23 Other ED visitors suggested that due to limited availability of the primary care physician, they had to visit the ED for care. “When I am sick and miss a day of work, I need to see a doctor that day. I can’t afford to be off work any longer. I need to feel better and go back to work the next day.”22 “It is easier to come out here [to the ED]. At least here I know I will be seen by a doctor.”23 Finally, patients indicated that the PCP had sent them to the ED in the past, “like the last time, I went and told my situation to my doctor; she told me to go to the hospital when you leave here.”2 Overall, the themes related to the primary care reflected inaccessibility in times of need and overall lack of efficiency in the provision of healthcare services resulting in inconvenience and delay in care for patients.

Theme 3: Advantages of the Emergency Department

Many ED visitors chose to come to the ED due to the availability of diagnostic tests, treatment, and medical expertise. Many ED visitors favored the opportunity to have the diagnostic and medical services necessary for their care readily available instead of having to attend several appointments or sites to receive the necessary services; the single-site care provided by the ED was considered to be a significant advantage. “My doctor cannot do X-rays of laboratory tests, while the ED has all the technical support.”22 “Everything is in one place.”22 “The doctors (referring to the ED physicians) perform things a lot faster.”22 “The ER is the quickest way to get checked out.”23 “I always get seen straightaway, no matter what... when I’m there, I know I’m alright, because I know they can pinpoint what it is and what’s doing it”.24

ED visitors sited convenience as another factor in using the ED for healthcare services. Work schedules, transportation opportunities, and child care concerns impacted the decision to seek care in the ED instead of the primary care physician office. Many ED visitors had already missed work due to their illness and did not want to miss any additional work time awaiting a primary care physician appointment. “It is really important to me because I need to get feeling better so I can get back to work tomorrow.”23 One mother noted, “I have four children and the ones I leave at home can’t stay there for a long time alone. If they are not at school, I will take them along with me. Sometimes my mom will keep them if she is at home.”23 “Our days are really long, that is why it is easier to come in at night”.26 Many ED visitors found the accessibility of the ED, with care available 24 h a day, 7 days a week particularly advantageous.

Theme 4: Quality of Hospital-Based Care and Fulfillment of Healthcare Needs

The review of the qualitative literature suggests that ED visitors have a specific perception of the quality of ED services and the likelihood of fulfillment of healthcare needs if a person visits the ED. “I wasn’t getting anywhere with my outpatient appointment, so my general practitioner said let’s try going to the ED and see if that speeds it up.. and it did!”27 “The hospital is where you go if you are sick or in pain at all, and the primary is just for checkups.”25 “I always feel that the hospital is safer.”28 The comments from the articles and themes identified in the metasynthesis suggest that the ED is perceived by patients as a place that will provide timely diagnoses, information, and pain control when one is unwell.

DISCUSSION

The metasynthesis provides unique, distinct insight into patient’s perspectives on where they choose to seek acute care. By collapsing data across several qualitative studies, we were able to collectively bring together data from multiple sites and patients in different countries. We found the reasons patients visit the ED over primary care included (1) urgency of the medical condition, (2) barriers to accessing primary care, (3) advantages of the ED, and (4) fulfillment of medical needs and quality of care in the ED. The themes identified in the articles in this metasynthesis were pervasive across different healthcare settings and delivery systems. Countries represented in the articles included the USA, France, Northwest England, Germany, and Australia, which have differing approaches to healthcare access, insurance, and delivery. Despite the different healthcare systems included in the metasynthesis, common themes across articles emerged.

Our metasynthesis has provided an alternative overarching perspective about the phenomenon of patients who choose to visit the ED instead of primary care. Although some have suggested that ED visitors may be clogging the ED with conditions that could be treated more efficiently in other healthcare settings,30, 31 our metasynthesis of the limited data available suggests that patients often have specific, cogent reasons for deciding to visit the ED. Moreover, they have fears, anxiety, and concerns about acute pain and illnesses necessitating emergent medical care. In these acute circumstances, they may not have ready access to a primary care provider, and/or they may have even been referred by a healthcare provider to the ED. Patients identified the ED as a “haven” with highly skilled providers capable of diagnosing acute conditions in a timely fashion. The view of the ED as an efficient diagnostic center may also be shared by primary care providers who have limited diagnostic tools and options in their offices and send patients to the ED for advanced procedures and testing. Patients may have work, family, or socioeconomic constraints that only allow them to pursue acute care services in the evening and on the weekend, when their only option for acute healthcare services is the ED. The overarching theme of the metasynthesis is that visits to the ED for acute care services are multifactorial in nature, and the ED is an important critical link in the chain of acute healthcare delivery, providing access to care 24 h a day 7 days a week for both patients in need of services and healthcare providers referring their patients to the ED for diagnostic evaluation and further care.

To our knowledge, there has not been any similar comprehensive metasynthesis of the qualitative studies on this important topic. The topic of nonurgent use of the ED has been one of significant interest with the development of algorithms to identify “nonurgent” visits and the potential to tax or penalize individuals using the ED for nonemergent conditions instead of going to primary care. However, data have indicated that providing primary care access is beneficial but insufficient to reduce ED visits.32 This is likely due to the fact that primary care access and availability are entirely different concepts in the “real world” for patients trying to address acute care needs.32 Starfield has suggested that good primary care includes easy accessibility, patient-focused care over time, comprehensive services, and coordination of consultative or subspecialty care. Without all of these components, timely medical care is threatened and the patient may resort to the ED for acute care services.33 Some investigators have suggested that patients “are generally good at deciding where to access care” and indicated “inappropriate choices are generally a function of complex socioeconomic factors and shortcomings in the unscheduled care system”.34, 35 Our data would seem to support this notion, with patients evaluating opportunities for acute care needs in the context of their socioeconomic status including work and family obligations as well as insurance status and making the best decisions they can regarding acute care services.

Our metasynthesis is an important step forward in identifying common themes for the patient-centered selection for healthcare delivery for acute care needs. These data suggest that there are many factors outside of the medical diagnosis that influence the patient’s decision about where to seek acute care. In this era of healthcare reform, there may be opportunities to modify the acute care delivery system in the USA, and the use of this type of patient-centered data to guide future directions in acute care delivery system is critical to successfully ensure “safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable” healthcare as recommended by the Institute of Medicine.15

Our study has limitations. We did not include materials that were unpublished, were in languages other than English, or used mixed methods. Exclusion of these studies may have resulted in an unanticipated bias in the theme results we identified in the metasynthesis. The scope, quantity, and quality of the qualitative studies included in the review are a limitation as not all themes related to patient choices between primary care and the ED may have been elucidated in these studies, thereby impacting results. Despite these limitations, we believe our use of a multidisciplinary team, including nursing, social work, and physicians, to conduct this metasynthesis is advantageous. Evaluation of the literature by our multidisciplinary team may have facilitated an interpretation more interdisciplinary in nature, and a multifaceted, interdisciplinary approach will be especially important as interventions are contemplated to help improve the acute care delivery system.

CONCLUSIONS

In this qualitative metasynthesis, reasons patients visit the ED over primary care included (1) urgency of the medical condition, (2) barriers to accessing primary care, (3) advantages of the ED, and (4) fulfillment of medical needs and quality of care in the ED. The themes identified in the articles were pervasive across different healthcare settings and delivery systems. To facilitate successful patient access and use of primary care, restructuring of the acute care delivery system to help effectively meet patients’ healthcare needs utilizing patient-identified advantages of the ED may be beneficial.

Contributors

There are no contributors to the manuscript that did not meet authorship criteria. Specific contributions were as follows: study concept and design: JAV, JJ, and EPH; acquisition of data: JAV, KLR, JJ, and MLB; analysis and interpretation of data: JAV, KLR, JJ, MLB, AAG, and EPH; drafting of the manuscript: JAV; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: JAV, KLR, JJ, MLB, AAG, and EPH; statistical analysis: JAV, KLR, JJ, and MLB; obtained funding: JAV; administrative, technical, or material support: JAV and EPH.

Funders

This study was supported in part by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Dr. Jody Vogel [K08HS023901]).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations: Presented, in part, at the Academy Health Research Meeting, Boston, Massachusetts, June 2016.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pitts Stephen R., Carrier Emily R., Rich Eugene C., Kellermann Arthur L. Where Americans Get Acute Care: Increasingly, It’s Not At Their Doctor’s Office. Health Affairs. 2010;29(9):1620–1629. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rising KL, Hudgins A, Reigle M, Hollander JE, Carr BG. “I’m just a patient”: fear and uncertainty as drivers of emergency department use in patients with chronic disease. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68:536–543. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen PW. Where have all the primary care doctors gone? New York Times. Available at: http://well.blogs.nytimes.com/2012/12/20/where-have-all-the-primary-care-doctors-gone/. Accessed May 8, 2019.

- 4.Asplin Brent R. Insurance Status and Access to Urgent Ambulatory Care Follow-up Appointments. JAMA. 2005;294(10):1248. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uscher-Pines L, Pines J, Kellermann A, et al. Emergency department visits for nonurgent conditions: systematic literature review. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19:47–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Derlet RW, Richards JR, Kravitz RL. Frequent overcrowding in US emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:151–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.White House. President Barack Obama. Remarks by the president on health care reform. 2010. Available at:https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/remarks-president-health-care-reform. Accessed May 8, 2019.

- 8.Starfield B. Primary Care: Balancing Health Needs, Services, and Technology. Rev. ed. New York (NY): Oxford University Press: 1998, p. 55–74.

- 9.Bodenheimer T. Coordinating care: a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1064–71. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr0706165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grumbach K, Bodenheimer T. A primary care home for Americans: putting the house in order. JAMA. 2002;288:889–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.7.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berenson RA, Rich EC. U.S. approaches to physician payment: the deconstruction of primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25:613–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1295-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsia RY, Kellermann AL, Shen YC. Factors associated with closures of emergency departments in the United States. JAMA. 2011;305:1978–85. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein SK, Huckins DS, Liu SW, Pallin DJ, Sullivan AF, Lipton RI, et al. Emergency department crowding and risk of preventable medical errors. Intern Emerg Med. 2012;7(2):173–80. doi: 10.1007/s11739-011-0702-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sun BC, Hsia RY, Weiss RE, Zingmond D, Liang LJ, Han W, et al. Effect of emergency department crowding on outcomes of admitted patients. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;61:605–11. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institute of Medicine . Crossing the Quality Chiasm: a New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2001. pp. 5–6. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandelowski M, Barroso J. Handbook for Synthesizing Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–359. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCormick J, Rodney P, Varcoe C. Reinterpretations across studies: an approach to meta-analysis. Qual Health Res. 2003;13:933–944. doi: 10.1177/1049732303253480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorne S, Jensen L, Kearney MH, Noblitt G, Sandelowski M. Qualitative metasynthesis: reflections on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qual Health Res. 2004;14:1342–1365. doi: 10.1177/1049732304269888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noblit GW, Hare RD. Meta-Ethnography: Synthesizing Qualitative Studies. London: Sage; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Letts L, Wilkins S, Law M, Stewart D, Bosch J, Westmorland M: Guidelines for Critical Review Form: Qualitative Studies (Version 2.0). Hamilton: McMaster University; 2007. Available athttp://srs-mcmaster.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/Guidelines-for-Critical-Review-Form-Qualitative-Studies.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2019.

- 22.Durand AC, Palazzolo S, Tanti-Hardouin N, Gerbeaux P, Sambuc R, Gentile S. Nonurgent patients in emergency departments: rational or irresponsible consumers? Perceptions of professionals and patients. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:525. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howard MS, Davis BA, Anderson C, Cherry D, Koller P, Shelton D. Patients’ perspective on choosing the emergency department for nonurgent medical care: a qualitative study exploring one reason for overcrowding. J Emerg Nurs. 2005;31:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jen.2005.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hunter C, Chew-Graham C, Langer S, Stenhoff A, Drinkwater J, Buthrie E, Salmon P. A qualitative study of patient choices in using emergency health care for long-term conditions: the importance of candidacy and recursivity. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93:335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kangovi S, Barg FK, Carter T, Lang JA, Shannon R, Grande D. Understanding why patients of low socioeconomic status prefer hospitals over ambulatory care. Health Aff. 2013;32:1196–1203. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koziol-McLain J, Price DW, Weiss B, Quinn AA, Honigman B. Seeking care for nonurgent medical conditions in the emergency department: through the eyes of the patient. J Emerg Nurs. 2000;26:554–563. doi: 10.1067/men.2000.110904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowthian JA, Smith C, Stoelwinder JU, Smit DV, McNeil JJ, Cameron PA. Why older patients of lower clinical urgency choose to attend the emergency department. Intern Med J. 2013;43:59–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02842.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmeidhofer M, Mockel M, Slagman A, Frick J, Ruhla S, Searle J. Patient motives behind low-acuity visits to the emergency department in Germany: a qualitative study comparing urban and rural sites. BMJ Open. 2016;6:e013323. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shaw EK, Howard J, Clark ED, Etz RX, Arya R, Tallia AF. Decision-making processes of patients who use the emergency department for primary care needs. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24:1288–1305. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LaCalle E, Rabin E. Frequent users of emergency departments: the myths, the data, and the policy implications. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisman R. Straining emergency rooms by expanding health insurance. Science. 2014;343:252–253. doi: 10.1126/science.1249341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rust G, Ye J, Baltrus P, Daniels E, Adesunloye B, Fryer GE. Practical barriers to timely primary care access. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1705–1710. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.15.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Starfield B. Primary care: is it essential? Lancet. 1994;344:1129–1133. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90634-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramlakhan S, Mason S, O’Keeffe C, Ramtahal A, Ablard S. Primary care services located with EDs: a review of effectiveness. Emerg Med J. 2016;p33:495–503. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Cooke M, Fisher J, Dale J, et al. Reducing Attendances and Waits in Emergency Departments: a Systematic Review of Present Innovations. Warwick: The University of Warwick; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Creswell J. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2013. [Google Scholar]