Abstract

Deep neck space infections (DNSI) are serious diseases that involve several spaces in the neck. These are commonly seen in low socioeconomic group with poor oral hygiene, and nutritional disorders. These are bacterial infections originating from the upper aerodigestive tract. The incidence of this disease was relatively high before the advent of antibiotics. Treatment of DNSI includes antibiotic therapy, airway management and surgical intervention. Management of DNSI is traditionally based on prompt surgical drainage of the abscess followed by antibiotics or nonsurgical treatment using appropriate antibiotics in the case of cellulitis. This study was conducted to investigate the age and gender, clinical symptoms, site involved, etiology, co-morbidities, bacteriology, complications and outcomes in the patients of DNSI. A prospective study of deep neck space infections was conducted during the period July 2017 to July 2018 on the patients who attended the outpatient department and were admitted as inpatient in Safdarjung hospital, New Delhi. 40 Cases with DNSI all ages and both genders were included in the study. Patients who didn’t require surgical intervention to drain pus were excluded. All parameters including age, gender, co-morbidities, presentation, site, bacteriology, complications, and investigations were studied. Due to advent of antibiotics, deep neck space infections are in decreasing trend. The common age group found to be affected is in 2nd and 3rd decade in our study. Out of all deep neck space infections, submandibular space infections were common (37.5%) followed by peritonsillar infections (12.5%). Infection of deep neck space remains fairly common and challenging disease for clinicians. Prompt recognition and treatment of DNSI are essential for an improved prognosis. Odontogenic and tonsillopharyngitis are the commonest cause. Key elements for improved results are the prompt recognition and early intervention. Special attention is required to high-risk groups such as diabetics, the elderly and patients with underlying systemic diseases as the condition may progress to life-threatening complications.

Keywords: Deep neck space infections, Odontogenic infections, Submandibular space infections, Peritonsillar abscess, Incision and drainage

Introduction

Deep neck space infection (DNSI) refers to an infection in the potential spaces and fascial planes of the neck, either with abscess formation or cellulitis [1]. DNSI can be categorized into retropharyngeal, peritonsillar, masseteric, pterigopalatine maxillary, parapharyngeal, submandibular, parotid and floor of mouth abscesses [2]. These are bacterial infections originating from the upper aerodigestive tract and involving the deep neck spaces. The incidence of this disease was relatively high before the advent of antibiotics, requiring prompt recognition and early interventions [3]. The primary sources of infections of deep neck spaces are the dentition and tonsils, other sources may be from salivary glands, malignancies and foreign bodies. Commonly follows infections like dental caries, tonsillitis and trauma to head and neck or in intravenous drug abusers. Odontogenic infection is one of the most common causes especially in developing countries [4].

DNSI are usually polymicrobial in nature. Streptococci, Peptostreptococcus species, Staphylococcus aureus, and anaerobes are the most commonly cultured organisms from DNSI [5, 6]. Clinical manifestations of DNSI depend on the spaces involved, and include pain, fever, malaise, fatigue, swelling, odynophagia, dysphagia, trismus, dysphonia, otalgia, and dyspnea [7].

Descending necrotizing mediastinitis is the most feared complication; it results from retropharyngeal extension of infection into the posterior mediastinum. Septic shock is associated with a 40–50% mortality rate [8]. Furthermore, suppurative thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein associated with pulmonary septic embolism, thrombosis of the cavernous sinus and erosion of the carotid artery have been reported [9].

Treatment of DNSI includes antibiotic therapy, airway management and surgical intervention. Management of DNSI is traditionally based on prompt surgical drainage of the abscess followed by antibiotics or nonsurgical treatment using appropriate antibiotics in the case of cellulitis [10]. Proper diagnosis and prompt management can effectively overcome the disease and provide a cure without complications. However, for this to be possible, otorhinolaryngologists must have detailed knowledge of the presentation, etiology, investigations and access to appropriate medical and surgical interventions. The purpose of our study was to share our experience in terms of presentation, clinical trends, common sites involved, bacteriology, management, complications, and outcomes.

Materials and Methods

We studied 40 patients prospectively who were admitted and treated for DNSI in the ear, nose and throat (ENT) department from July 2017 to July 2018 at our tertiary referral institute. In all the cases included in this study, the patient underwent a surgical procedure to drain pus. We excluded patients who had cervical infection not requiring surgical drainage, such as cellulitis or superficial infection. Patients of all age groups and both genders were included. We studied following parameters—age, gender, clinical symptoms, site involved, etiology, co-morbidities, bacteriology, culture growth, complications and outcomes. All patients were initiated on treatment with amoxicillin, clavulanate, and metronidazole; the treatment regimen was later modified based on a culture and sensitivity report. Statistical evaluations were performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21.0.

Results

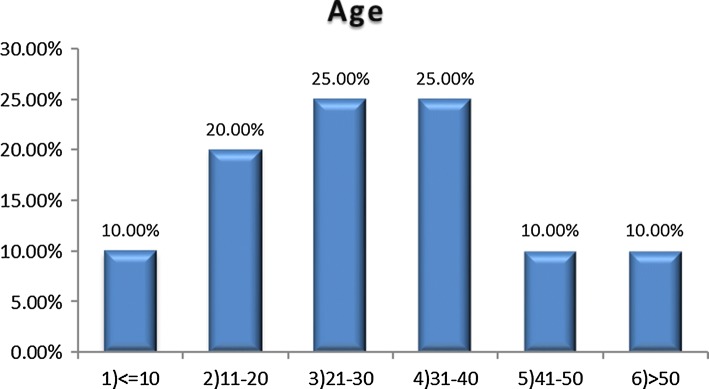

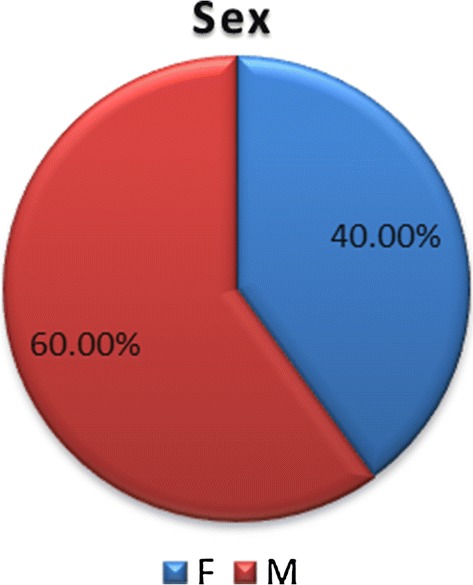

Of the 40 patients, 24 were male and 16 female, 60% and 40% respectively. Their ages ranged from 3 months to 72 years with a mean age of 24.6 years. Most patients were in their 2nd and 3rd decade (Figs. 1, 2).

Fig. 1.

Age distribution of patients

Fig. 2.

Sex distribution of patients

With respect to demographic distribution, 30 patients (70%) belonged to rural background and 10 patients (30%) were from urban background.

Among all 40 patients, 12 patients (30%) were tobacco smokers, 6 patients (15%) were tobacco chewers, 4 patients (10%) were alcoholic. As for co-morbidities 6 patients (15%) had diabetes mellitus, 4 (10%) had hypertension, 2 (5%) suffered with coronary artery disease; 2 (5%) patients were infected with pulmonary tuberculosis and 1 patient (2.5%) with hepatitis C.

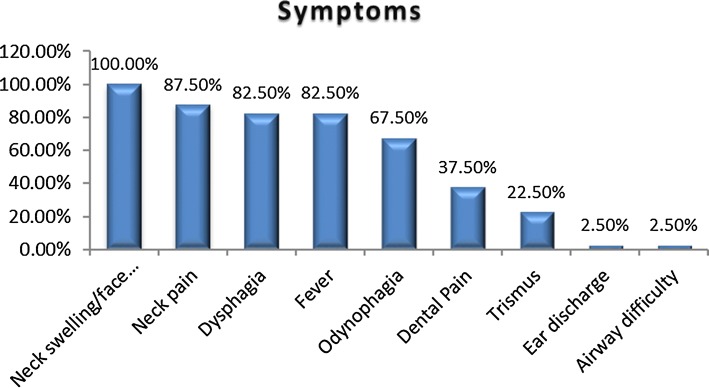

The symptoms were neck and/or facial edema in all patients, local pain in 35 patients (87.5%), fever in 33 patients (82.5%), dysphagia in 33 patients (82.5%), odynophagia in 27 patients (67.5%), dental pain in 15 patients (37.5%), trismus in 9 patients (22.5%) difficult breathing in 1 patient (2.5%) and ear discharge in 1 patient (2.5%) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Symptoms of deep neck space infections patients

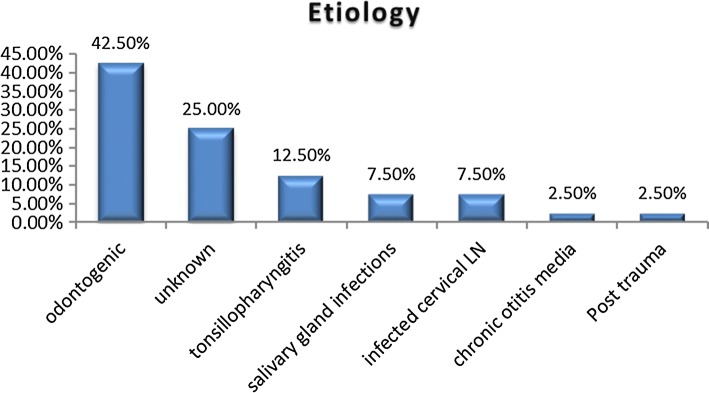

The most common etiology in our study was found to be odontogenic focus of infection constituting 42.5% cases. In 25% of cases etiology remained unknown. Next common etiology was tonsillopharyngitis infection (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Etiological factors in DNSI patients

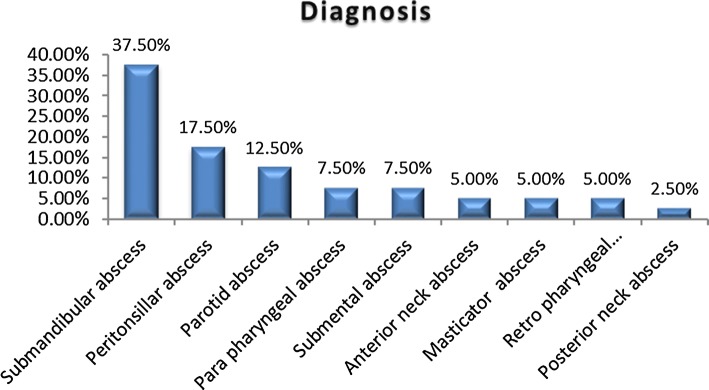

The most common clinical presentation was submandibular space infection (Ludwig’s angina), in 15 patients (37.5%), followed by peritonsillar abscess in 7 patients (17.5%), parotid abscess in 5 patients (12.5%), parapharyngeal abscess in 3 patients (7.5%), retropharyngeal abscess in 2 patients (5%), submental abscess in 3 patients (7.5%), anterior triangle neck abscess in 2 patients (5%), masticator abscess in 2 patients (5%), and abscess in the posterior region of the neck in 1 patient (2.5%) (Fig. 5). The majority of patients 28 (70%) underwent a computed tomography (CT) scan, 12 patients (30%) had a neck ultrasound. Routine investigations were performed in all patients.

Fig. 5.

Location of the abscess in DNSI patients

All the forty patients, underwent intervention consisting of initial needle aspiration followed by incision and drainage, and a pus specimen obtained from these patients was sent for culture and sensitivity analysis. Twenty-seven (67.5%) patients had positive culture results. The most common organism cultured was Staphylococcus including methicillin resistant strain (MRSA) (9, 22.5%), followed by Steptococcus (8, 20%), Polymicrobials (4, 10%), Pseudomonas (2, 5%), Anaerobes (2, 5%), E. coli (1, 2.5%), and Proteus (1, 2.5%). No bacterial growth was found in 13 patients (32.5%).

All 40 patients were given broad spectrum intravenous antibiotics, which were later updated based on culture and sensitivity report.

Complications were encountered in a few patients. One patients had upper airway obstruction, another had necrotizing fascitis and two of the patients had skin necrosis. The mean hospital stay was 5.2 days, with a minimum of 3 days and a maximum of 20 days.

Discussion

Review of literature shows many similarities and few differences as to results of our study compared with other similar studies. Of the 40 patients, 24 were males and 16 females, 60% and 40% respectively which is consistent with studies by Sethi et al. [11], Meher et al. [12] and Parischar et al. [13] which showed male preponderance. The range of age in our study was from 3 months to 72 years with mean age of 24.6 years. Most of the patients in our study were in their 2nd decade and 3rd decade of life. This is similar to study by Meher et al. [12] and Parischar et al. [13] in which majority patients were in the third and fourth decade of life respectively.

The most commonly found systemic diseases were diabetes (15%) and systemic arterial hypertension (10%). This correlates to the study by Sethi et al. [11] who reported a 16% to 20% incidence of diabetes. Systemic arterial hypertension, which may be associated with heart and lung diseases, is not given much importance; these factors may have an influence on the morbidity and mortality of DNI. Twelve patients (30%) were tobacco smokers, six patients (15%) were tobacco chewers. These habits result in poor oral hygiene and affect the host’s vulnerability to systemic diseases by the formation of subgingival biofilms acting as reservoirs of Gram-negative bacteria, and through the periodontium acting as a reservoir of inflammatory mediators [14].

The clinical picture of infection with edema of the neck, local pain, odynophagia, fever, trismus, a poor health status, associated or not with a primary condition is similar to that found in the literature [11, 15, 16].

The most common etiology in our study was found to be odontogenic focus of infection, 42.5% cases. Parhiscar et al. odontogenic infections were declared as the most common cause of DNSI (43%). Huang et al. [6], Marioni et al. [17] and Eftekharian et al. [15] reported that odontogenic problems were the most common causative factor for DNSI, in 42, 38.8 and 49% cases, respectively. Studies by Sethi et al. [11] and Har-El et al. [18] also showed the major cause of DNSI to be dental in origin. Thus, our study results are consistent with those of these previous studies.

Odontogenic focus was followed by cause of infection being tonsillopharyngitis (12.5%). The cause remained unknown in 25% of the cases notwithstanding a detailed clinical history, thorough physical examination and radiological studies. The oropharynx was probably the site of origin in these cases. Previous studies have also shown a significant proportion (around 16% to 39%) of DNI of unknown origin [11, 13, 19].

The most common site of DNSI involved in our study was submandibular space (37.5%) followed by peritonsillar abscess (17.5%) which is in conjunction with the studies done by Eftekharian et al. [15], Bakir et al. [16] and Alexandre et al. [20]. Next common DNSI in our study were parotid abscess (12.5%) and parapharyngeal abscess (7.5%).

The most commonly isolated organisms are mostly part of the normal oropharyngeal flora [19]. In our study, staphylococcus aureus including MRSA strain (22.5%) was the most common isolated organism followed by streptococcus species (20%) which is similar to study done by Alexandre et al. [20]. Culture was sterile in 32.5% cases which is in conjunction to, as mentioned in previous studies (27 to 40%) [11, 21]. This was probably due to the indiscriminate use of antibiotics prior to hospital admission and the high doses of endovenous antibiotics before surgery [11].

A computed tomography with contrast is the most appropriate imaging tool, not only for the diagnosis of deep neck space infections, but also to show the extent of disease. Contrast CT scan is still the appropriate imaging to be done since it helps in correct diagnosis indicating the extent of disease, differentiating cellulitis from abscess and helps evaluate any complication. CT scan also helps to decide whether surgical intervention is indicated [22]. Although it has high sensitivity, the test specificity is low, for example in cases of lymph node clusters without associated abscess, which can lead to unnecessary surgical procedures [23]. Ultrasound also plays an important role in the detection of abscess formation [10, 22]. In our study, a CT scan was performed in 70% patients and ultrasound was performed in 30% cases.

Treatment of DNSI involves early surgical drainage of purulent abscess via an external incision along with use of antibiotics [1, 15]. In our study, all patients were initiated empirically on intravenous antibiotic therapy with amoxicillin, clavulanic acid, and metronidazole, which was later modified according to the culture and sensitivity report. Surgical intervention was carried out in all the patients included in the study. According to previous studies by Parhiscar et al. [13], Eftekharian et al. [15] and Har-El et al. [18] surgical intervention is required in approximately 79, 90 and 100% of cases, respectively.

Airway management is crucial when patients present trismus or signs of upper airway obstruction, particularly in Ludwig’s angina, in which there is edema of the oral floor due to bilateral submandibulary space infection. In our study, tracheostomy was performed in 2.5% of cases, in the study by Eftekharian et al. [15] tracheostomy was required in 8.8% cases. Parhiscar et al. [13] analyzed 210 patients with neck abscesses and reported a need for tracheostomy under anesthesia in 44% of cases, which demonstrates the severity of this condition. A tracheal intubation with rigid laryngoscopy may be difficult in these patients due to the possibility of distortion in the airway anatomy, tissue rigidity, and a limited access to the mouth. Thus, the tracheostomy must always be considered whenever there is respiratory difficulty. Sometimes attempting intubations can worsen an already damaged airway [24].

Conclusion

We conclude from our current study that odontogenic and tonsillopharyngitis are the most common cause for DNSI. In developing countries, lack of adequate nutrition, poor oral hygiene, tobacco chewing, smoking and beetle nut chewing has led to an increased prevalence of dental and periodontal diseases. It remains fairly common and challenging disease for clinicians. Prompt recognition and treatment of DNI are essential for an improved prognosis. Key elements for improved results are the identification of signs and symptoms and morbid factors. Special attention is required to high-risk groups such as diabetics, the elderly and patients with underlying systemic diseases as the condition may progress to life-threatening complications. In our study most common site involved was submandibular space followed by peritonsillar space. All patients should be initiated on treatment with empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy, which should be updated later according to the culture and sensitivity report. All patients with a significant abscess on the CT scan require surgical intervention. Complication rate is very low with proper antibiotic coverage and timely surgical intervention. Tracheostomy should be considered if airway protection is needed. Prevention of DNSI can be achieved by making the population aware of dental and oral hygiene and encouraging regular consultations for dental infections.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent has been obtained from subjects included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Wang LF, Kuo WR, Tsai SM, Huang KJ. Characterizations of life threatening deep cervical space infections: a review of one hundred ninety six cases. Am J Otolaryngol. 2003;24(2):111–117. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2003.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gorjón PS, Pérez PB, Martín ACM, Dios JCP, Alonso SE, Cabanillas MIC. Infecciones cervicales profundas. Revisión de 286 casos. Acta Otorrinolaringol Esp. 2012;63:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durazzo M, Pinto F, Loures M, Volpi E, Nishio S, Brandao L, et al. Deep neck space infections. Rev Ass Med Bras. 1997;43:119–126. doi: 10.1590/S0104-42301997000200008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong TY. A nationwide survey of deaths from oral and maxillofacial infections: the Taiwanese experience. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1999;57:1297–1299. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2391(99)90863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ungkanont K, Yellon RF, Weissman JL, Casselbrant ML, Gonzalez VH, Bluestone CD. Head and neck space infections in infant and children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112(3):375–382. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70270-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Huang TT, Liu TC, Chen PR, Tseng FY, Yeh TH, Chen YS. Deep neck infection: analysis of 185 cases. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;26(10):854–860. doi: 10.1002/hed.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasegawa J, Hidaka H, Tateda M, Kudo T, Sagai S, Miyazaki M, et al. An analysis of clinical risk factors of deep neck infection. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2011;38(1):101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen MK, Wen YS, Chang CC, Huang MT, Hsiao HC. Predisposing factors of life-threatening deep neck infection: logistic regression analysis of 214 cases. J Otolaryngol. 1998;27(3):141–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blomquist IK, Bayer AS. Life-threatening deep fascial space infections of the head and neck. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 1988;2(1):237–264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mayor GP, Millan JMS, Martinez VA. Is conservative treatment of deep neck space infections appropriate? J Head Neck. 2001;23(2):126–133. doi: 10.1002/1097-0347(200102)23:2<126::AID-HED1007>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sethi DS, Stanley RE. Deep neck abscesses: challenging trends. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:138–143. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100126106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meher R, Jain A, Sabharwal A, Gupta B, Singh I, Agarwal I. Deep neck abscess: a prospective study of 54 cases. J Laryngol Otol. 2005;119(04):299–302. doi: 10.1258/0022215054020395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parhiscar A, Harel G. Deep neck abscess: a retrospective review of 210 cases. Ann Otolo Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110(11):1051–1054. doi: 10.1177/000348940111001111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anil S, Al-Ghamdi HS. The impact of periodontal infections on systemic diseases. An update for medical practitioners. Saudi Med J. 2006;27(6):767–776. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eftekharian A, Roozbahany NA, Vaezeafshar R, Narimani N. Deep neck infections: a retrospective review of 112 cases. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;266:273–277. doi: 10.1007/s00405-008-0734-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakir S, Tanriverdi MH, Gun R, Yorgancilar AE, Yildirim M, Tekbas G, et al. Deep neck space infections: a retrospective review of 173 cases. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012;33(1):56–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marioni G, Staffieri A, Parisi S, Marchese RR, Zuccon A. Rational diagnostic and therapeutic management of deep neck infections: analysis of 233 consecutive cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2010;119(3):181–187. doi: 10.1177/000348941011900306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Har-El G, Aroesty JH, Shaha A, Lucente FE. Changing trends in deep neck abscess: a retrospective study of 110 patients. Oral Surg Med. 1994;77(5):446–450. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(94)90221-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sakaguchi M, Sato S, Ishiyama T, Katsuno S, Taguchi K. Characterization and management of deep neck infections. Int J Oral Max Surg. 1997;26(2):131–134. doi: 10.1016/S0901-5027(05)80835-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suehara AB, Gonçalves AJ, Alcadipani FAMC, et al. Deep neck infection: analysis of 80 cases. Rev Bras Otorrinolaringol. 2008;74(2):253–259. doi: 10.1590/S0034-72992008000200016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin C, Yeh FL, Lin JT, Ma H, Hwang CH, Shen BH, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis of the head and neck: an analysis of 47 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107(7):1684–1693. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200106000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith JL, Hsu JM, Chang J. Predicting deep neck space abscess using computed tomography. Am J Otolaryngol. 2006;27:244–247. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2005.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller WD, Furst IM, Sandor GKB, Keller MA. A prospective, blinded comparison of clinical examination and computed tomography in deep neck infections. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1873–1879. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199911000-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osborn TM, Assael LA, Bell RB. Deep space neck infection: principles of surgical management. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin N Am. 2008;20:353–365. doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]