Abstract

To review the changing indications, decannulation rates, complications and mortality in pediatric tracheotomies. Medical records of children who underwent primary or revision tracheotomy from April 2003 to December 2015 were retrospectively analyzed. Patient characteristics including age, sex, preoperative diagnosis and indications for tracheotomy. The complications, mortality and decannulation rates for the tracheotomies were studied. There were 101 patients who underwent tracheotomy over a period of 13 years. Out of these, complete data was available for 99 patients. There were 61 males and 38 females and the age of children who underwent tracheotomy on an average ranged from 2 months to 16 years. The indications were divided into five categories: airway obstruction, cardiopulmonary, craniofacial, neurological, and trauma. Out of the 99 patients, 92 patients underwent an elective tracheotomy while only 7 patients underwent an emergency tracheotomy. Fifty-eight patients could be successfully decannulated. 13 patients in our study died during the course of treatment, however, none of the deaths could be directly attributed to the tracheotomy. Three patients developed peristomal granulations requiring intervention, 1 patient had a severe stomal infection, and one patient had a tracheocutaneous fistula requiring surgical closure. Over the last few decades, widespread use of vaccinations and improved pediatric and neonatal intensive care has revolutionized child healthcare in developing countries like ours. This impact is reflected in our finding that neurological impairment has displaced obstructive airway (of infective etiology) as the most common indication for pediatric tracheotomy in the present era.

Keywords: Pediatric, Tracheotomy, Tracheostomy, Indications, Changing trends, Indian

Introduction

Pediatric tracheotomy as a surgical procedure, has been known since ancient Greek times. In the nineteenth and twentieth century, the procedure was primarily performed as an emergency life-saving procedure in children with acute airway obstruction, due to diphtheria and epiglottitis, requiring temporary establishment of an airway [1, 2]. However, in the modern surgical era, the indications for pediatric tracheotomy have undergone significant metamorphosis [3].

Due to the widespread practice of vaccinations and advancements in non-invasive modalities of ventilation, the spectrum today has drastically shifted to most tracheostomies being elective and long-term. This shift can also be attributed to various other medical innovations, which have resulted in an increased survival of neonates and infants with complex anomalies and chronic diseases [4].

However, there has been no published data from India in the past decade with respect to the changing trends for pediatric tracheotomies. The objective of our study is to review the indications for tracheotomy in a large cohort of pediatric patients over the past decade at a tertiary care center in Bangalore.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patient Population

A retrospective chart review was conducted on pediatric patients who had a tracheotomy at at a tertiary care center in Bangalore between 2003 and 2015. All patients not more than 18 years at the time of undergoing tracheotomy were included in the study. Patients having incomplete medical records were excluded from the study.

Peri-Tracheotomy Assessment

The records were reviewed and patient characteristics were studied including patient age, sex, preoperative diagnosis and primary indication for tracheotomy. The patients were categorized into five groups based on the indication for tracheotomy: (1) airway obstruction (2) cardiopulmonary, (3) craniofacial anomalies, (4) neurological impairment, (5) traumatic injury. The conditions included in each of these categories are listed in Table 1. Patients having multiple indications were classified according to the primary indication for tracheotomy.

Table 1.

Conditions included in each indication group

| Airway obstruction (n = 17) | Cardiopulmonary (n = 24) | Craniofacial (n = 2) | Neurological (n = 46) | Trauma (n = 10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subglottic stenosis | Prematurity | Goldenhar syndrome | Guillain–Barre syndrome | Motor vehicle accidents |

| Subglottic hemangioma | Pneumonia/ARDS | Crouzon’s syndroma | Viral encephalitis | Laryngotracheal trauma |

| Laryngomalacia | Congenital heart Disease | Seizures | Maxillofacial trauma | |

| Tracheobronchomalacia | Septicemia | Tumor | ||

| Laryngeal cleft | Chronic lung disease | LOCHHS | ||

| Laryngeal papilloma | Hypoxic encephalopathy | |||

| B/L Abductor palsy | Leighs disease | |||

| Cystic hygroma | Charcot Marie tooth disease | |||

| Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disoder | ||||

| Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis |

The procedure was classified as elective or emergency. We also studied the complications, decannulation rates and mortality in our patient population.

Statistical Analysis

Proportions were compared using Chi square or Fisher’s exact test, depending on their applicability. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Mann–Whitney test was applied for comparison of age in different indication groups. Analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS statistics (version 22.0).

Results

One hundred and one pediatric patients underwent tracheotomy during the period January 1, 2003–December 31, 2015, out of which complete data was available for 99 patients. Of these 61 were males and 38 were females. At the time of tracheotomy patients were aged between 2 months and 16 years, with a median age of 4 years (Table 2). The most common indication for tracheotomy was neurological impairment (48%), followed by cardiopulmonary disease (24%), airway obstruction (15%), trauma (11%) and craniofacial anomalies (2%). Only 9 patients underwent an emergency tracheostomy, the remaining 92 being elective.

Table 2.

Demographics, indications and outcome of study groups

| Total (n = 99) | Airway obstruction (n = 17) | Cardiopulmonary (n = 24) | Craniofacial (n = 2) | Neurological (n = 46) | Trauma (n = 10) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median in years) | 4.0 | 0.6 | 2.5 | 1.2 | 8.0 | 6.0 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.603 | ||||||

| Male | 61 | 12 | 14 | 1 | 26 | 8 | |

| Female | 38 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 20 | 2 | |

| Emergency tracheotomy | 7 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | < 0.001 |

| Reason for tracheotomy | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Prolonged intubation | 51 | 5 | 16 | 0 | 22 | 8 | |

| Respiratory failure | 22 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 18 | 0 | |

| Stridor | 11 | 9 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Pulmonary toilet | 6 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Aspiration | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Failed extubation | 7 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | |

| Complication | 0.768 | ||||||

| Peristomal granulation | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Stomal infection | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Tracheocutaneous fistula | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Weak voice | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Failed decannulation | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| Retracheotomy | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Decannulation | 0.180 | ||||||

| Yes | 58 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 29 | 9 | |

| No | 26 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 12 | 1 | |

| Death | 13 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0.201 |

| Lost to follow-up | 13 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 0 |

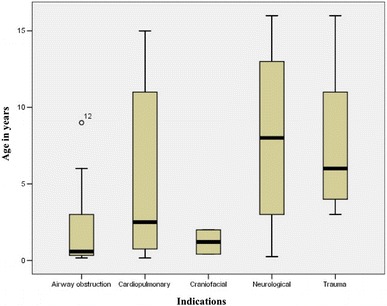

Children undergoing tracheotomy for airway obstruction and craniofacial anomalies were the youngest with a median age of 0.6 and 1.2 years respectively. On the other hand, tracheotomies were done at an older age in the neurologically impaired (median = 8 years) and post-traumatic group (median = 6 years) (Fig. 1) Seventeen patients underwent a tracheotomy for airway obstruction, of which none were of inflammatory origin.

Fig. 1.

Box plot of age distribution in the tracheotomy indication groups

Three patients developed peristomal granulations which required excision and revision of tracheotomy. One patient had a severe stomal infection which responded to intravenous antibiotics. One patient had a persistent tracheocutaneous fistula, which required surgical closure. There were 13 deaths (13.1%), none of which were tracheotomy related. Of the 99 patients, 58 patients (58.6%) were successfully decannulated.

Discussion

In spite of numerous conflicting reports originating from all over the world, there has been a general trend towards increasing number of pediatric tracheotomies being done for prolonged intubation in the neurologically impaired, with an associated decline in tracheotomies performed for airway obstruction [4, 5]. This has been attributed to reduced infections of the upper airway as well as improvement in neonatal and pediatric intensive care.

Carron et al. [2] published their experience from 1988 to 1998, stating neurological impairment and prolonged ventilation as the most common indication in their study. Ozmen et al. [5] published an extensive 37-year review from Turkey from 1968 to 2005, which found that although upper airway obstruction was overall the most common indication for pediatric tracheotomy, since the 1990s, chronic ventilation had superseded it. Butnaru et al. [6] from France, published their study around the same timeframe. They found prolonged intubation to be the most common indication for tracheotomy (57%) associated with a decrease in frequency in tracheotomies done for airway obstruction. A 12-year analysis by Ang et al. [7] from Singapore, also found access for assisted ventilation to be the most common indication for tracheotomy.

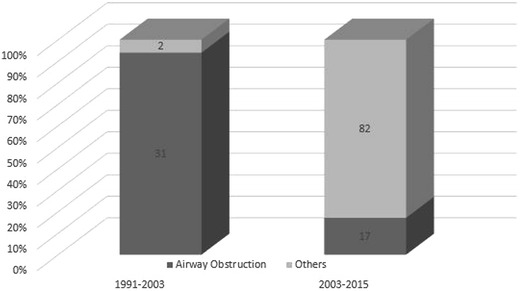

In our study, neurological impairment was the most common indication for tracheotomy, followed by cardiopulmonary disease. Our study showed a changing trend over the years, with more number of tracheotomies being done for neurological impairment and a corresponding decrease in those done for airway obstruction. In addition, we also noted that no tracheotomy has been done for airway obstruction of infective origin, since 2003. These findings mirror the epidemiological data from most other studies originating from the western world, which is reassuring for a developing nation like ours. Alladi et al., published the only study on pediatric tracheotomies originating from India, and found airway obstruction to be the most common indication. Thirty-one out of the 33 patients included in their study underwent tracheotomy for airway obstruction [8]. They reviewed all their pediatric tracheotomies done over a period of 13 years, from 1991 to 2003. We reviewed the 13 years after this study. The fact that our study showed contrasting results, further reiterates the improvement in pediatric intensive care in our country (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the changing indications for tracheotomy between the study by Alladi et al. (1991–2003), and our study (2003–2015)

Interestingly, there have been a few studies in recent years showing that the pendulum is swinging back towards airway obstruction as the most common indication for tracheotomy. Lawrason et al. [9] in their study, considered improvement in practice patterns among their neonatologists, with improvement in management of prematurity and BPD to be the plausible explanation for this change. Mahadevan et al. [10] in their 17-year review, found the main indication for pediatric tracheotomy was airway obstruction, which accounted for 70% of procedures, whereas tracheotomy for chronic ventilation accounted for only 30% of procedures. Craniofacial dysmorphisms constituted 47% of all causes of airway obstruction, while subglottic stenosis was the cause of airway obstruction in only 21% of cases. In their experience, this change was the consequence of improvement in neonatal intensive care of premature infants, which has in turn resulted in increased survival of neonates and premature infants, including those with severe congenital craniofacial and airway anomalies. Also, the trend of tracheotomizing these children at a younger age prevented post intubation subglottic stenosis. Considering the time lag between medical advances in a developed nation and a developing nation, we may experience such a paradigm shift in the near future. This shift might also have a bearing on the post-tracheostomy management, with decannulation becoming more challenging.

The average age at tracheostomy differs for each indication due to the varied pathophysiology behind these disorders. Funamura et al. [4] found that children requiring tracheotomy for neurological impairment or trauma are older. In our study, we found a similar distribution, where patients with airway obstruction and craniofacial anomalies were significantly younger than children with neurological impairment and trauma. This is an expected finding as traumatic injuries generally occur after the child starts walking, thus, seen in children older than 1 or 2 years. On the other hand, craniofacial anomalies and airway obstruction tend to present at a younger age, thus requiring tracheotomy early in the course of disease.

There are several limitations to our study, the retrospective nature being one of them. This entails reliance on perioperative documentation for placing the patient into a particular group.

Secondly, many patients have co-existing diseases with multiple indications for tracheotomy, making it difficult to classify them into a particular group. Thirdly, being an urban tertiary care center in a country without a definite referral pattern, some patients are tracheotomized at a primary or secondary care center, with no reliable perioperative documentation. Lastly, our small sample size could have restricted our ability to find a statistically significant result.

Conclusion

Widespread use of vaccinations along with improved pediatric and neonatal intensive care over the last decade has resulted in neurological impairment replacing airway obstruction as the most common indication for tracheotomy between 2003 and 2015. This reflects the improvement in the health care practices in our country. However, with further medical advances, we may anticipate the pendulum to swing back towards airway obstruction and craniofacial anomalies, and thereby, prepare ourselves for a more difficult post-tracheotomy course.

Acknowledgements

The statistical analysis was done by Mrs. Kusum Chopra.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

All authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

This is a retrospective study. For this type of study formal consent is not required.

References

- 1.Line WS, Hawkins DB, Kahlstrom EJ, MacLaughlin EF, Ensley JL. Tracheotomy in infants and young children: the changing perspective 1970–1985. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:510–515. doi: 10.1288/00005537-198605000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carron JD, Derkay CS, Strope GL, Nosonchuk JE, Darrow DH. Pediatric tracheotomies: changing indications and outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1099–1104. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200007000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogilvie LN, Kozak JK, Chiu S, Adderley RJ, Kozak FK. Changes in pediatric tracheostomy 1982–2011: a Canadian tertiary children’s hospital review. J Pediatr Surg. 2014;49:1549–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Funamura JL, Durbin-Johnson B, Tollefson TT, Harrison J, Senders CW. Pediatric tracheotomy: indications and decannulation outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:1952–1958. doi: 10.1002/lary.24596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozmen S, Ozmen OA, Unal OF. Pediatric tracheotomies: a 37-year experience in 282 children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:959–961. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butnaru CS, Colreavy MP, Ayari S, Froehlich P. Tracheotomy in children: evolution in indications. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:115–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ang AHC, Chua DYK, Pang KP, Tan HKK. Pediatric tracheotomies in an Asian population: the Singapore experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:246–250. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.03.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alladi A, Rao S, Das K, Charles AR, D’Cruz AJ. Pediatric tracheostomy: a 13-year experience. Pediatr Surg Int. 2004;20:695–698. doi: 10.1007/s00383-004-1277-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lawrason A, Kavanagh K. Pediatric tracheotomy: are the indications changing? Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;77:922–925. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahadevan M, Barber C, Salkeld L, Douglas G, Mills N. Pediatric tracheotomy: 17 year review. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;71:1829–1835. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2007.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]