Abstract

To compare the outcomes of various surgical approaches to resect sinonasal inverted papilloma and to discuss their advantages and disadvantages. A retrospective chart review of 61 consecutive patients with sinonasal inverted papilloma was performed. Surgical treatment included non-demucosation endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS), demucosation ESS, endonasal medial maxillectomy (EMM), Draf type 3, Caldwell-Luc surgery, Denker, Killian, and lateral rhinotomy. Recurrence rates were compared between endonasal and external approaches and between demucosation and non-demucosation. After the first curative surgery, the non-demucosation ESS, endonasal demucosation (demucosation ESS, EMM, and Draf type 3), and external surgery showed recurrence rates of 61.5%, (8/13), 0.0% (0/21), and 7.4% (2/27), respectively. A significantly lower recurrence rate was observed in the endonasal demucosation (p < 0.001) and in the demucosation ESS group (p < 0.001) in comparison with the non-demucosation ESS. However, as for recurrence rate, no statistically significant difference was observed between endonasal surgery and external surgery (p = 0.162). Demucosation is a better strategy for the treatment of inverted papilloma than is non-demucosation. Demucosation is the key procedure for preventing recurrence.

Keywords: Inverted papilloma, Endonasal approach, External approach, Krouse staging

Introduction

Sinonasal papilloma is a benign tumor, and it is divided into 3 types: inverted, exophytic, and columnar cell papilloma. Inverted papilloma is the most frequently observed variant (52–61%), followed by exophytic (35–34%) and columnar cell papilloma (13–5%) [1, 2]. A potential causative factor of sinonasal papilloma is the human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, based on the detection of its DNA [3]. Inverted papilloma presents features of possible synchronous and metachronous malignancy, typically squamous cell carcinoma or other less common tumors, such as transitional cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, mucoepidermoid carcinoma, or verrucous carcinoma [1, 4]. The rate of malignant transformation in inverted papilloma ranges between 8 [1] and 11% [4]. Dysplasia has also been reported in 8% of inverted papilloma cases [1]. To date, the relevance of HPV is being elucidated, but anti-viral agents seem to be ineffective and the most effective therapeutic strategy is surgery. Several surgical procedures have been attempted, with both external and endonasal approaches. An external approach may cause a sense of discomfort within the buccal region, facial scaring, facial deformation, and oro-nasal fistula. On the other hand, an endonasal approach does not cause these complications. In fact, an endonasal approach does not need any facial incision and can decrease crusting, facial swelling, the need to resect healthy tissue, the incidence of epiphora, and bleeding [5]. However, both surgical approaches have advantages and disadvantages. In this paper, the outcomes of surgical approaches and the countermeasures to their disadvantages are discussed.

Methods

This study involved the retrospective data of 61 consecutive patients with sinonasal inverted papilloma, who underwent surgery to resect in the Department of Otolaryngology at our institution between 2005 and 2014. The study population included 39 men and 22 women with an age ranging from 28 to 85 years (median age: 62 years) at the time of diagnosis. We excluded the patients who did not undergo surgery to resect the tumor after its pathological confirmation as inverted papilloma. Patients with sinonasal carcinoma were excluded in this study. We focused particularly on the advantages and disadvantages of the surgical approaches. The outcomes of surgical approaches were investigated. The tumor extension of inverted papilloma was classified using the staging system by Krouse [6], as follows: T1, the tumor is confined to the nasal cavity. (The tumor can involve only one wall of the nose or be extensive within the nose but must not have spread to the sinuses or extranasal areas on endoscopic and/or CT examination.) (Figure 1a); T2, the tumor is limited to the medial and superior portions of the maxillary sinus and/or involves the ethmoid sinus, with or without involvement of the nasal cavity, as noted on endoscopic and/or CT examination (Fig. 1b); T3, the tumor involves the lateral, inferior, anterior, or posterior walls of the maxillary sinus, the sphenoid sinus, or the frontal sinus, with or without involvement of the ethmoid sinus or nasal cavity, as noted on endoscopic and/or CT examination (Fig. 1c); T4, the tumor extends outside the confines of the nose and/or paranasal sinuses to involve adjacent, contiguous structures (e.g., the orbit, intracranial compartment, or pterygomaxillary space), as noted on endoscopic and/or CT examination.

Fig. 1.

Krouse staging. a T1. Coronal CT image demonstrates the tumor arising from the middle nasal turbinate in the right nasal cavity. b T2. Coronal CT image show the tumor in the left ethmoid sinus, slightly invading medial wall of the left maxillary sinus. c T3. Coronal CT image show the tumor of the right maxillary sinus with the hyperostosis on the surface of the maxillary sinus

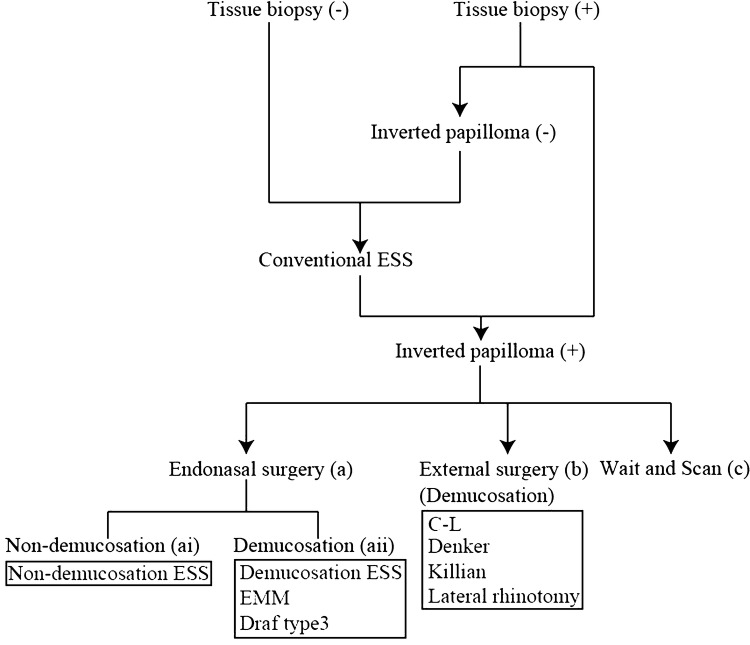

Diagnosis was confirmed by pathological findings according to the flow diagram of therapeutic strategy (Fig. 2). When inverted papilloma was suspected, a tissue biopsy was performed preoperatively in 34 patients. Inverted papilloma was pathologically confirmed in 33 patients. The one patient whose pathology by tissue biopsy did not show inverted papilloma and 27 patients whose tissue biopsy was not examined preoperatively underwent conventional ESS because they were provisionally diagnosed with chronic rhinosinusitis with polyp. When the resected polyps during conventional ESS demonstrated the inverted papilloma histopathologically, patients were finally diagnosed with inverted papilloma. In this study, conventional ESS is defined as the ESS that enlarges the orifice of the sinus and removes the polyps and the membranous and bony partition to create a good ventilation route into the sinus. In total, inverted papilloma was pathologically confirmed in 61 patients, and then endonasal surgery (a in Fig. 2) or external surgery (b in Fig. 2) were performed, otherwise patients were followed-up by wait and scan (c in Fig. 2). Surgeries for inverted papilloma were divided into endonasal surgery (a in Fig. 2) and external surgery (b in Fig. 2). Endonasal surgery was divided into two groups: non-demucosation (ai in Fig. 2) and demucosation (aii in Fig. 2). ESS was also divided into 2 types: non-demucosation ESS and demucosation ESS. Non-demucosation ESS was defined as the ESS that enlarges the orifice of the sinus and shaves the tumorous membrane and the bony and membranous partition within the sinus using microdebriders. Demucosation ESS was defined as the ESS that removes all the membrane around the tumor on the walls of the involved sinus using a raspatory in addition to a microdebrider and/or burr. Endonasal demucosation was performed by demucosation ESS, EMM, and Draf type 3 [7]. During EMM and Draf type 3, the membrane around the tumor was removed (demucosation). The external surgeries were Caldwell-Luc surgery (C-L), Denker, Killian, and lateral rhinotomy, which are a procedure of demucosation. In C-L and Denker, all the membrane around the tumor on the walls of the involved sinus was removed, and in Killian and lateral rhinotomy, the membrane around the tumor on the walls was removed.

Fig. 2.

Therapeutic strategy

Five well-experienced surgeons, who had experience of more than 10 years in the field of sinonasal surgeries, performed or supervised the surgeries. Surgical indications for each stage were different for each surgeon. For stage 1, surgeon 1 performed demucosation ESS and surgeons 2-5 did non-demucosation ESS. For stage 2, surgeon 1 performed demucosation ESS, surgeons 2-4 did demucosation ESS or external surgery if it was difficult to remove the tumor by ESS, and surgeon 5 did non-demucosation ESS or external surgery if it was difficult to remove the tumor by ESS. For stage 3, surgeon 1 performed demucosation ESS or external surgery (Denker and/or Killian) until 2008 and EMM and/or Draf type 3 after 2009. Surgeon 2 performed external surgery until 2013, and EMM after 2014. Surgeons 3–4 did demucosation ESS or external surgery. Surgeon 5 did non-demucosation ESS or external surgery.

Only patients with a follow-up of at least 30 months after surgery were included. Data were expressed as mean ± standard error values. The statistical methods (Fisher’s exact probability test for assessment of differences between two groups; all reported p values are two-tailed) were performed using Ekuseru-Toukei 2012 software (Social Survey Research Information Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan).

Results

Krouse Staging System and Operative Methods

Sixty-one patients with inverted papilloma were classified according to the Krouse staging system, with 3 cases in T1, 21 in T2, 37 in T3, and 0 in T4. The performed treatments are shown in Table 1. In 3 patients of the T1 group, one patient underwent non-demucosation ESS and 2 patients underwent demucosation ESS. In 21 patients of the T2 group, 6 patients underwent non-demucosation ESS, 7 patients underwent demucosation ESS, 6 patients underwent C-L, and 2 patients underwent lateral rhinotomy.

Table 1.

Krouse staging system, treatment, and recurrence

| Staging (n) | Treatment | n | Recurrence (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| T1 (3) | Endonasal surgery | ||

| Non-demucosation | |||

| Non-demucosation ESS | 1 | 0 | |

| Demucosation | |||

| Demucosation ESS | 2 | 0 | |

| T2 (21) | Endonasal surgery | ||

| Non-demucosation | |||

| Non-demucosation ESS | 6 | 3 | |

| Demucosation | |||

| Demucosation ESS | 7 | 0 | |

| External surgery | |||

| Demucosation | |||

| C-L | 6 | 0 | |

| Lateral rhinotomy | 2 | 0 | |

| T3 (37) | Endonasal surgery | ||

| Non-demucosation | |||

| Non-demucosation ESS | 6 | 5 | |

| Demucosation | |||

| Demucosation ESS | 7 | 0 | |

| EMM | 4 | 0 | |

| EMM + Draf type3 | 1 | 0 | |

| External surgery | |||

| Demucosation | |||

| C-L | 9 | 0 | |

| Denker | 5 | ||

| Denker + Killian | 1 | 1 | |

| Killian | 2 | 1 | |

| Lateral rhinotomy | 2 | 0 |

ESS Endoscopic sinus surgery, C-L Caldwell-Luc Surgery and EMM endonasal medial maxillectomy

Among 37 patients of the T3 group, 6 patients underwent non-demucosation ESS by the following: demucosation ESS (7 cases), EMM (4 cases), EMM and Draf type 3 (1 case), C-L (9 cases), Denker (5 cases), Denker & Killian (1), Killian (2 cases), or lateral rhinotomy (2 cases).

Recurrence Rate

Among the T1, T2, and T3 cases, recurrence occurred in 16.4% of cases (10/61) between 3 and 12 months after the first curative surgery (median, 6 months). T1 cases did not show recurrence (Table 2). T2 cases showed recurrence after non-demucosation of endonasal surgery at 50% (3/6) but not after demucosation of endonasal surgery and external surgery. T3 cases showed recurrence after non-demucosation of endonasal surgery at 83.3% (5/6), no recurrence after demucosation of endonasal surgery, and recurrence after external surgery at 7.4% (2/27).

Table 2.

Recurrence rate after surgery

| Staging | Endonasal surgery | External surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-demucosation | Demucosation | Demucosation | |

| T1 | 0.0% (0 of 1) | 0.0% (0 of 2) | – |

| T2 | 50.0% (3 of 6) | 0.0% (0 of 7) | 0.0% (0 of 8) |

| T3 | 83.3% (5 of 6) | 0.0% (0 of 12) | 10.5% (2 of 19) |

| Total | 61.5% (8 of 13) | 0.0% (0 of 21) | 7.4% (2 of 27) |

Endonasal surgery showed a recurrence rate of 23.5% (8/34), whereas external surgery led to a recurrence rate of 7.4% (2/27) (Table 3). Endonasal surgery and external surgery did not show a significant difference (p = 0.162). With respect to non-demucosation versus demucosation, non-demucosation resulted in a recurrence rate of 61.5% (8/13), whereas demucosation of endonasal and external surgery resulted in 4.2% (2/48). Non-demucosation demonstrated a significantly higher recurrence than demucosation (p < 0.001). Next, with respect to endonasal surgery, endonasal non-demucosation showed a recurrence rate of 61.5%, whereas endonasal demucosation showed 0.0% (0/21) (Table 2). Endonasal demucosation showed a significantly lower recurrence (0.0%, 0/21) than non-demucosation ESS (61.5%, 8/13) (p < 0.001). Then, when compared to endonasal demucosation with external surgery (demucosation), endonasal demucosation (0%, 0/21) and external demucosation (7.4%, 2/27) showed no significant difference (p = 0.497). A high recurrence rate of 61.5% was found in patients that had undergone non-demucosation ESS (Table 3). On the other hand, demucosation ESS resulted in no recurrences. Demucosation ESS showed a significantly lower recurrence than non-demucosation ESS (p < 0.001). EMM and Draf type 3 also showed no recurrences. After Denker, recurrence occurred in a case out of 6 (16.7%), whereas Killian showed a recurrence in 2 cases out of 3 (66.7%). Finally, after C-L, 9 patients showed no recurrence, whereas lateral rhinotomy showed no recurrence in all 4 cases.

Table 3.

Recurrence rate

| Endonasal surgery | 23.5% (8 of 34) |

| Non-demucosation | |

| Non-demucosation ESS | 61.5% (8 of 13) |

| Demucosation | |

| Demucosation ESS | 0.0% (0 of 16) |

| EMM | 0.0% (0 of 5) |

| Draf type 3 | 0.0% (0 of 1) |

| External surgery | 7.4% (2 of 27) |

| Demucosation | |

| Denker | 16.7% (1 of 6) |

| Killian | 66.7% (2 of 3) |

| C-L | 0.0% (0 of 9) |

| Lateral rhinotomy | 0.0% (0 of 4) |

ESS Endoscopic sinus surgery, C-L Caldwell-Luc Surgery and EMM endonasal medial maxillectomy

Recurrence Sites After Curative Surgery

Recurrence occurred in 10 patients after curative surgery. Two recurrences were observed in the maxillary sinus, 7 cases in the ethmoidal sinus, 4 cases in the frontal sinus, and one in correspondence to the sphenoid sinus. In 6 cases, recurrence occurred in a single site, whereas 4 cases showed recurrences over 2 sites of the frontal and ethmoidal sinuses.

Discussion

In this study, no recurrence was observed following endonasal demucosation, external surgery of C-L, and lateral rhinotomy for the treatment of inverted papillomas. On the other hand, non-demucosation ESS showed high recurrent rates. During non-demucosation ESS, the microdebrider was used only to remove the tumor, excluding both raspatories and burrs, without the complete resection of all the mucosa. Therefore, it is likely that a portion of mucosa containing the tumor remained after non-demucosation ESS. To minimize recurrence, the removal of all the mucosa from the pathological sinus is considered necessary. Recurrence rates do not seem to depend on the type of approach (i.e., endonasal vs. external), but rather on the entity of resection (demucosation vs. non-demucosation). The demucosation procedure is important and inevitable for preventing recurrence.

Tomenzoli et al. [8] showed their endonasal approach and stressed the importance of a radical extirpation of the lesion together with the subperiosteal plane and the underlying bone, because of the possible presence of micro-lesions in the underlying bony tissue. He concluded that the resection of bony tissue in addition to the tumor is the best strategy to minimize recurrence. However, the disadvantages of this strategy are breaking the bony barrier between the sinus and extranasal tissue and the risk of ocular and/or intracranial complications, especially in the lamina papyracea and the tegmen of the ethmoidal sinus. Therefore, the periosteum outside the sinus should be preserved intact, although parts of the periosteum sometimes tear. Then, a tumoral recurrence on the periosteum and/or outside the sinus through tearing sites would be quite difficult and risky to resect. Hyams [9] showed that inverted papillomas often have a limited attachment site. Therefore, Landsberg et al. [10] recommended an attachment-oriented endoscopic surgical approach. However, Pagella et al. [11] showed no significant difference in the recurrence rate between an attachment-oriented endoscopic approach and demucosation, with the first approach showing a shorter operation time. If the attachment site is confirmed, an attachment-oriented endoscopic surgical approach is a reasonable procedure; otherwise, the demucosation of all the sinuses involved by the inverted papilloma is necessary.

Yousuf and Wright [12] and Sham et al. [13] reported that CT showed hyperostosis and/or osteitis at the attachment site. In particular, Yousem et al. [14] reported that MRI can define the extent of the inverted papilloma. Ojiri et al. [15] also described the cerebriform pattern of inverted papilloma on MRI. Instead, according to Maroldi et al. [16], MRI reveals bony remodeling or bony erosion, thus suggesting the site of attachment. In conclusion, both CT and MRI can preoperatively predict the attachment site [12, 13, 16], although both imaging methods are not perfect, especially in the case of a large tumor. Therefore, clinical findings during surgery are the most important to determine the attachment site [11, 13, 17, 18].

An endonasal approach cannot be performed unless the sinus is visible, but the advent of endoscopy advanced the endonasal approach, providing the advantages of illumination, high-magnification, and a wide-angle view [5]. Since high definition television technique has been developed, the vision field has become clear enough to observe the mucosae. Endoscopy can allow a clear view of the ethmoid sinus, the posterior, lateral, and superior walls of the maxillary sinus, and the sphenoid sinus. However, even today, an endoscopic view of the anterior, medial, and inferior walls of the maxillary sinus as well as the lateral part of the frontal sinus may still be difficult. Even if such areas can be visualized, it is extremely difficult to approach them by surgical tools (e.g., forceps, elevators) through the maxillary natural orifice or the frontal sinus infundibulum. Lesions involving the medial wall of the maxillary sinus can be resected by EMM together with the medial wall [17]. When anterior wall lesions cannot be approached, the inferior and lateral walls of the maxillary sinus can be more easily visualized and approached by EMM. After EMM, the anterior lateral walls of the maxillary sinus can be often observed, although it is sometimes difficult to approach those lesions [19]. Liu et al. [19] performed a combined EMM and frontal sinus wall resection via a pyriform crest approach, and they defined it as endonasal endoscopic anterior and medial maxillectomy. The frontal sinus is the most difficult sinus to be approached by ESS. In particular, the lateral part of the frontal sinus is narrow and bending. Therefore, it is difficult to visualize all the surfaces inside the frontal sinus. For this purpose, the Draf technique or the modified transnasal endoscopic Lothrop procedure may be useful methods to resect the floor of the frontal sinus and the inter-frontal sinus septum and to spread out the frontal sinus infundibulum wide enough to approach the frontal sinus [7, 20]. Stankiewicz and Girgis [21] and Han et al. [18] reported the treatment of frontal sinus inverted papillomas by the Lothrop procedure. However, the development of the frontal sinus varies among patients. In case of a well-developed frontal sinus, it may be difficult to approach the lateral wall, so that an external Killian approach or a combined Killian and endonasal approach may be necessary. However, the combination of the Killian approach and ESS showed a high recurrence rate in our study, with a predilection for the frontal sinus infundibulum, which is prone to be a blind spot as a narrow structure. The Draf technique and the Lothrop procedure can remove the bone near to the frontal sinus infundibulum so that this area can be more easily visualized and approached. Therefore, the Draf technique and the Lothrop procedure are the best approaches for poorly to moderately developed frontal sinuses. Instead, the combination of Killian and Draf techniques or Killian and Lothrop procedures are probably more suitable for well-developed frontal sinuses.

External surgery has the advantage of directly approaching the tumor with a smaller blind area. However, these techniques are usually performed with the unaided eye. Therefore, small portions of tumorous mucosa might be overlooked. On the other hand, ESS has many blind areas, although mucosa can be magnified and closely inspected. EMM and/or the Draf technique can relieve the disadvantages of blind areas, thus allowing their visualization. Endonasal approaches other than the conventional ESS represent the best treatment option for inverted papilloma. Instead, when the lateral wall of the frontal sinus cannot be visualized, the Killian technique is necessary. Moreover, when the anterior wall of the maxillary sinus cannot be approached, external approaches such as the Denker procedure or transnasal endoscopic anterior and medial maxillectomy [19] become necessary. If external approaches are chosen, endoscopy or microscopy may still be helpful to prevent micro-lesions from being overlooked.

Surgical tools have been developed in response to the developments of endoscopy. Microdebriders and endonasal burr have extended the surgical approachable area. Microdebriders can precisely remove soft tissue and bone while suctioning and irrigating [22]: they shave and suction the tissues, successively. If suctioned tissues (which may include tumor cells) are nullified, accurate histological diagnosis cannot be performed and tumorous tissue may be overlooked. Inverted papilloma sometimes exists solely in the sinonasal cavity. However, the tumor is commonly associated with chronic rhinosinusitis. Vorasubin et al. [1] reported that 50% of inverted papilloma cases are associated with chronic rhinosinusitis. Chronic inflammation and/or chronic rhinosinusitis are supposed to be involved in the pathogenesis of the sinonasal papilloma [23]. The coexistence of such a condition should be kept in consideration during surgery. The differential diagnosis of rhinosinusitis and inverted papilloma is important, and it may be possible by MRI, especially T2-weighted MRI [14]. CT image of inverted papilloma are similar in density to images of sinusitis (Fig. 3a). And T1-weighted MRI of inverted papilloma and rhinosinusitis presents a similar intermediate signal intensity mass (Fig. 3b). On the other hand, T2-weighted MRI of inverted papilloma shows an intermediate-to-slightly high signal intensity mass, which is different from the region of high signal intensity suggesting inflammatory mucosa or secretion (Fig. 3c).

Fig. 3.

Differential diagnosis between inverted papilloma and sinusitis. A-63-year woman with left maxillary inverted papilloma (T3). Axial CT image a and axial T1-weighted MRI b show a mass in the left nasal cavity and maxillary sinus, with a slight lesion in the right maxillary sinus. Axial T2-weighted MRI demonstrates an intermediate-to-slightly high signal intensity mass (arrow) indicating inverted papilloma. The high signal intensity area on the ipsilateral (left) side (asterisk) suggests obstructed secretion or secondary inflammatory mucosa in the maxillary sinus. The high signal intensity area (arrow head) on the contralateral (right) maxillary sinus indicates inflammatory mucosa

Nowadays, during ESS for chronic rhinosinusitis, debriders are commonly used, and surgeons tend not to send all surgical specimens for pathological examination. In order not to overlook a coexisting tumor, surgeons should examine as many pathological specimens as possible.

Finally, this study has some limitations: small population size, a retrospective study, different strategies among surgeons, and no long-term follow up periods. It is necessary to investigate the long-term recurrence rate using a large population in the further study.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

Masafumi Ohki and Shigeru Kikuchi declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Vorasubin N, Vira D, Suh JD, Bhuta S, Wang MB. Schneiderian papillomas: comparative review of exophytic, oncocytic, and inverted types. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2013;27:287–292. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2013.27.3904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roh HJ, Procop GW, Batra PS, Citardi MJ, Lanza DC. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of inverted papilloma. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18:65–74. doi: 10.1177/194589240401800201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Syrjänen K, Syrjänen S. Detection of human papillomavirus in sinonasal papillomas: systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2013;123:181–192. doi: 10.1002/lary.23688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mirza S, Bradley PJ, Acharya A, Stacey M, Jones NS. Sinonasal inverted papilloma: recurrence, and synchronous and metachronous malignancy. J Laryngol Otol. 2007;121:857–864. doi: 10.1017/S002221510700624X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Busquets JM, Hwang PH. Endoscopic resection of sinonasal inverted papilloma: a meta-analysis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:476–482. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2005.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krouse JH. Endoscopic treatment of inverted papilloma: safety and efficacy. Am J Otolaryngol. 2001;22:87–99. doi: 10.1053/ajot.2001.22563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Draf W. Endonasal micro-endoscopic frontal sinus surgery: the fulda concept. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;2:234–240. doi: 10.1016/S1043-1810(10)80087-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tomenzoli D, Castelnuovo P, Pagella F, et al. Different endoscopic surgical strategies in the management of inverted papilloma of the sinonasal tract: experience with 47 patients. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:193–200. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200402000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hyams VJ. Papillomas of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses. A clinicopathological study of 315 cases. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1971;80:192–206. doi: 10.1177/000348947108000205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landsberg R, Cavel O, Segev Y, Khafif A, Fliss DM. Attachment-oriented endoscopic surgical strategy for sinonasal inverted papilloma. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:629–634. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pagella F, Pusateri A, Giourgos G, Tinelli C, Matti E. Evolution in the treatment of sinonasal inverted papilloma: pedicle-oriented endoscopic surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28:75–81. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.3985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yousuf K, Wright ED. Site of attachment of inverted papilloma predicted by CT findings of osteitis. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21:32–36. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sham CL, King AD, van Hasselt A, Tong MC. The roles and limitations of computed tomography in the preoperative assessment of sinonasal inverted papillomas. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:144–150. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yousem DM, Fellows DW, Kennedy DW, Bolger WE, Kashima H, Zinreich SJ. Inverted papilloma: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1992;185:501–505. doi: 10.1148/radiology.185.2.1410362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ojiri H, Ujita M, Tada S, Fukuda K. Potentially distinctive features of sinonasal inverted papilloma on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175:465–468. doi: 10.2214/ajr.175.2.1750465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maroldi R, Farina D, Palvarini L, Lombardi D, Tomenzoli D, Nicolai P. Magnetic resonance imaging findings of inverted papilloma: differential diagnosis with malignant sinonasal tumors. Am J Rhinol. 2004;18:305–310. doi: 10.1177/194589240401800508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamel RH. Transnasal endoscopic medial maxillectomy in inverted papilloma. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:847–853. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199508000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han JK, Smith TL, Loehrl T, Toohill RJ, Smith MM. An evolution in the management of sinonasal inverting papilloma. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1395–1400. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu Q, Yu H, Minovi A, et al. Management of maxillary sinus inverted papilloma via transnasal endoscopic anterior and medial maxillectomy. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2010;72:247–251. doi: 10.1159/000317033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gross WE, Gross CW, Becker D, Moore D, Phillips D. Modified transnasal endoscopic Lothrop procedure as an alternative to frontal sinus obliteration. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113:427–434. doi: 10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stankiewicz JA, Girgis SJ. Endoscopic surgical treatment of nasal and paranasal sinus inverted papilloma. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;109:988–995. doi: 10.1177/019459989310900603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McGarry GW, Gana P, Adamson B. The effect of microdebriders on tissue for histological diagnosis. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1997;22:375–376. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1997.00007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orlandi RR, Rubin A, Terrell JE, Anzai Y, Bugdaj M, Lanza DC. Sinus inflammation associated with contralateral inverted papilloma. Am J Rhinol. 2002;16:91–95. doi: 10.1177/194589240201600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]