Abstract

To compare the effectiveness of over-the-counter normal saline with nasal decongestant drops for the symptomatic relief of nasal congestion, and to determine if nasal drops used alone are effective in the treatment of patients suffering from nasal congestion. Prospective, randomized double blinded study. Otorhinolaryngology Outpatient Department. Patients suffering from nasal congestion and similar symptoms such as nasal discharge, dryness, crusting, sneezing, itching and loss of smell. Resolution of symptoms based on visual analog scale and objective findings on anterior rhinoscopy. Chi-square test was done for comparison between the saline and decongestant groups. Subgroup analysis was done for patients on additional medication such as antibiotics. The p value is 0.701671 for the effectiveness of saline against that of decongestant, thus no significant difference exists between them for the relief of nasal congestion. The p value is 0.007497 for those on antibiotics and those that were treated only with nasal drops, thus showing a significant difference (level of significance being p < 0.05). The effectiveness of both nasal saline and decongestant drops in bringing about relief of nasal congestion is similar, and both of them may also cause headache though the mechanism is not well understood from this study. Relief might be primarily obtained with the help of oral medication and not the use of nasal drops.

Level of evidence: Single-center randomized trial, level II b.

Keywords: Nasal drops, Saline, Decongestant, Intranasal preparations, Nasal congestion, Antibiotics, Devices

Introduction

Nasal congestion is a common symptom found in a variety of lesions ranging from acute catarrhal/viral rhinitis to chronic rhinosinusitis. Topical nasal medications like nasal drops have traditionally been used for the symptomatic relief of nasal congestion. Such drops are usually decongestant preparations available over the counter (OTC) and taken by patients for self medication, and therefore carry with them the potential for serious side effects. Most of these OTC medications do carry important and relevant patient information in the form of warning or caution, but not all users may read this or be able to understand its implications. They may be prescribed or used as self medication along with other commonly prescribed medications for colds and upper respiratory tract infections, such as antibiotics and anti-inflammatory agents. Users also range from the illiterate to the highly educated, and patient information may be given insufficient attention among all these different groups of users. Potential side effects may thus be largely unknown to the majority of the lay population that uses these forms of medications. Members of the medical profession too may not be fully aware of the pros and cons of many OTC preparations, especially nasal decongestants. Hence the objective of this study was to compare the effectiveness of OTC normal saline with nasal decongestant drops and to determine if either of them is useful as solitary therapy for the symptomatic relief of nasal congestion.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective, randomized double blinded study with an initially planned sample size of 100 (50 in each group, i.e. nasal decongestant and normal saline respectively). This was based on previous studies where a standard deviation of 2 would require 40 subjects in each arm to detect a minimum difference of 0.5 in the two arms [1]. To power it to 80% and p < 0.05 (two-tailed), only 20 in each arm would be required [1]. Also, most other studies had a sample size of 60–120 [1–5]. In order to account for a dropout rate of 10%, a sample size of 100 would thus be adequate. Institutional and ethics clearance were obtained for the study and it was registered with the national clinical trial registry. Informed consent was obtained from all the study participants. The parameters studied were symptomatic relief of symptoms on a 10- point visual analog rating scale provided on the patient questionnaire, complete resolution of symptoms using the same scale and examination findings on anterior rhinoscopy. Participants were asked to use the drops for a minimum of 3 days and preferably for 5 days unless local discomfort or similar issues were present. They were given a diary and pen to document the day to day relief or lack of it, and also how soon they were able to obtain relief from nasal congestion. The primary outcome was relief from nasal congestion. Any amount of relief was considered as a positive outcome. Secondary outcomes were relief from other symptoms such as nasal discharge, sneezing, dryness, crusting, itching and loss of smell.

Due to the apparent high rate of adverse effects and failure of relief with only nasal drops, discovered midway through the study, it was decided that the study would be terminated prematurely and the results for 60 subjects would be analyzed, since a sample size of 60 or less has been found to be sufficiently powered in most of the studies cited. Since the bottles were coded and randomized in batches of 10 each, equal numbers of saline and decongestant bottles were used for the recruited participants. The institutional review board (IRB) and the clinical trial registry were informed of the early termination.

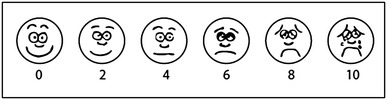

The study questionnaire, details of the of random allocation method and the CONSORT checklist for the study methodology are included as appendices. The symptom scale used was a visual analog scale (VAS) as shown in Figure 1 (Appendix 1). Patients were asked to circle the smiley on each day in the evening around 7 pm, from day 1 to day 5 and at least for 3 days. Those who stopped the drops after 3 days were asked the reason why, and this was either due to the fact that no relief had been obtained, or an adverse drug reaction ensued. The VAS was read as follows in terms of the relief obtained:

Excellent: 0–2; Good: 2–4; Fair: 4–6; Poor: 6–8; Nil: 8–10.

Any amount of relief obtained was considered as a positive outcome, and was recorded as ‘relief’ and confirmed on anterior rhinoscopy by resolution of nasal congestion. Any score more than 6 was considered ‘no relief’ and confirmed as congested mucosa on anterior rhinoscopy. Excellent relief was considered complete symptom resolution, and confirmed by absence of discharge and crusting on anterior rhinoscopy.

Results

The day to day relief obtained by the patients was analyzed on the basis of the VAS score on day 3. Chi-square test was done for comparison between the saline and decongestant groups. Subgroup analysis was done for patients on additional medication such as antibiotics.

A total of 24 patients obtained relief with nasal drops when antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs were also given, while 27 obtained relief with just nasal drops and in the absence of additional medications. In the first group, 16 patients obtained excellent relief, 6 good relief and 2 fair relief. In the second group, 10 obtained excellent relief while 11 had good relief and 6 had fair relief. A majority of the patients (n = 12) obtained relief right on the first day of use of the drops, and this was good (n = 3) or excellent (n = 9) and similar for both kinds of drops (n = 7 for saline and n = 5 for decongestant), with some progressing to excellent relief on day 2 or 3. 9 patients did not get any relief at all and were reevaluated. Patients having relief with the use of drops are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Amount of relief obtained with use of nasal drops, with or without additional medications respectively (na and nb in brackets)

| Saline | Decongestant | |

|---|---|---|

| Excellent | (na = 10); (nb = 7) | (na = 6); (nb = 3) |

| Good | (na = 4); (nb = 5) | (na = 2); (nb = 6) |

| Fair | (na = 1); (nb = 2) | (na = 1); (nb = 4) |

When stratified by group, the Chi square statistic is 7.1498. The p value is 0.007497 which is highly significant for a significance level of p < 0.05. Thus relief was primarily obtained with the help of oral medication and not the use of nasal drops (Table 2).

Table 2.

Relief obtained with saline, decongestants and additional medications

| Relief obtained | Saline | Decongestant |

|---|---|---|

| With antibiotics | 17 | 7 |

| Without antibiotics | 9 | 18 |

In the absence of additional medication, it was found that relief was obtained with nasal drops alone in 27 patients. Decongestants were effective in double the number of patients (n = 18) as compared to saline (n = 9). An adverse drug reaction, probably rebound congestion and headache, was seen in 3 patients who had used only decongestant drops (Table 3). Headache was also noticed in 1 patient who had used only saline drops, but this could not be explained satisfactorily, and the patient was referred to neurology for evaluation of the same.

Table 3.

Relief and adverse events (ADR) noted in the saline and decongestant groups

| No antibiotics given | Saline | Decongestant |

|---|---|---|

| Relief obtained; no ADR | 8 | 15 |

| Relief obtained; ADR present | 1 | 3 |

When relief brought about by saline and decongestant drops was examined as against an adverse drug reaction, the result was found to be similar, as shown in Table 3. The Chi square statistic is 0.1467. The p value is 0.701671 which is not significant for a significance level of p < 0.05.

Discussion

Synopsis of Key Findings

Even though it might be apparent that both saline and decongestant drops brought about relief, it actually becomes clear from analysis of the results that antibiotics might have had a large role to play. The effectiveness of both nasal saline and decongestant in bringing about relief of nasal congestion is more or less similar, and both of them may also cause adverse drug reaction (ADR) such as headache though the mechanism is not well understood from this study.

Strengths of the Study

Both nasal decongestants and saline drops for intranasal use are freely available in the market as OTC preparations, and even look similar in appearance, with prices within close range of each other. They are extremely popular with the public, many of whom resort to frequent use of such products without first visiting a doctor. They are also widely advertised in the media, both print and electronic. This study is the first of its kind comparing two such popular OTC nasal preparations, namely normal saline and decongestant, having similar names, external appearance and pricing. Only a color difference and relevant pharmacological information tell one apart from the other. There is no information on the respective bottles or dispensers regarding dosage and adverse effects, although certain websites do carry important information regarding these aspects of the above mentioned formulations.

Comparisons with Other Studies

Prabhu et al. [1] found similar results in patients undergoing nasal and sinus surgery who were post operatively treated with saline nasal douche or nasal decongestant drops. Both saline and decongestant preparations were found to be useful for the relief of nasal congestion following nasal surgery, especially nasal septal surgery. These patients commonly suffered from nasal discharge, sneezing or itching, loss of smell and facial pain for varying periods of time following the operation, and douching with either alkaline douches or decongestants was beneficial. Irrigation with saline also helped to rid the operative site of viscid mucus and crusts, and helped in humidification, moisturization and reduction of mucosal edema. The xylometazoline 0.1% in hydrochloride formulation is a potent vasoconstrictor thereby reducing mucosal swelling.

A Cochrane Database systematic review also revealed that though the common cold is a serious cause of morbidity and many forms of therapy are available commercially, a very limited number of studies have been done to examine the effects of a single oral dose of nasal decongestant given for the acute resolution of symptomatic nasal congestion. The authors of this systematic review, Tavernen and Latte [2], found that a single oral dose of nasal decongestant is adequate to relieve nasal congestion in adults. When continued beyond 3–5 days, however, rebound congestion might take place leading to drug overuse and possibly rhinitis medicamentosa. In severe cases, this might require surgical intervention.

Also, nasal douching with saline has been found to be effective in surgery for rhinosinusits [3] as well as chronic rhinosinusitis, [4] and could thus be considered for use in place of nasal decongestants. Egan et al. [5] found nasal irrigation with hypertonic saline beneficial in patients with various forms of rhinosinusitis. These studies were based on the responses of patients to a rating scale which, when used correctly, gives reliable results, as found by Price et al. [6].

Damiani et al. [7] noted that the ability of a person to perceive nasal airflow could be defined as a subjective sensation, because it is not uncommon to find that the perception of nasal obstruction is inconsistent with the physical examination of the interior of the nose. Only rhinomanometry is able to provide an objective assessment of the true nature of nasal airflow. The patient’s perception of airflow is at best an indirect measurement of nasal congestion. The subjective sensation of nasal congestion may be reliably assessed by means of a visual-analog scale (VAS) such as the one used in this study [6]. The VAS assigns a score to denote the extent of discomfort and may be used repeatedly and reproduced in a variety of settings. It is far more reliable than a closed response from the patient such as ‘feeling the same’, ‘feeling better’, or ‘feeling worse’.

Damiani et al. used Narivent, a medical device that is used to dispense a lubricant formulation into the nose [7]. The authors found that Narivent not only produced a subjective improvement in nasal airflow but also an objective decrease in the nasal resistance.

It is interesting to note that saline nasal irrigation has been tried for long periods, even up to 1 year, and then stopped in order to find if infection rates had come down. It was found that the infection rates had indeed decreased, but only after stopping the irrigations, and not when they were actually being carried out. The reason behind this has been proposed to be the reduction in the natural elements that provide local immunity in the nasal environment [8]. The authors also pointed out that varying strengths of saline from isotonic to hypertonic (3.5%) has been used by practitioners and researchers but the most efficacious saline concentration and method of delivery still remains elusive.

Tomooka et al. [9] used a pulsatile hypertonic nasal saline irrigation system with a Water Pik device and found it beneficial when used twice daily for 3–6 weeks. Talbot found that hypertonic saline increased the rate of mucociliary transport but normal saline was not able to achieve the same [10]. Also, a pulsatile method of delivery was more beneficial for removing bacterial contamination as compared to a bulb syringe [11]. Adam observed that any form of saline delivered by a spray method is not effective for relieving the symptoms of cold or sinusitis [12]. On the contrary, adverse drug reactions are rather common and include irritation, discomfort, earache, and saline pooling with subsequent drainage in the paranasal sinuses. Perhaps the best use of saline irrigation lies in the delivery of post-operative care to patients who have undergone endoscopic sinus surgery [9]. The authors recommend 6 weeks of saline irrigation without resorting to manual cleaning or suction, and adhesions are not found when this practice is adhered to properly. Others have proposed that nasal saline irrigation enhances the mucociliary transport mechanism [10], reduces mucosal edema and washes out the products and mediators of inflammation from the mucosal surfaces while removing the inspissated mucus [13, 14]. Nasal hyperthermia has also been advocated as treatment for the common cold and in cases of allergic rhinitis [15] but others have found no benefit from the use of steam inhalation in the relief of symptoms of common cold [14]. Numerous other methods have been used, from aminoglycosides [16] to vasoconstrictors to buffered saline, white corn syrup [17] and alkalol [18], but none of these has been found supreme. Similarly, devices such as the Neti pot and Sinu Cleanse are also circumspect. Last but not the least, many of these intranasal preparations including those used in this study are over-the-counter medicines.

Clinical Applicability of the Study

Though this study was prematurely terminated with 60 participants and did not meet its originally proposed sample size of 100, some clinical facts became apparent quite early. The benefits of commonly available over-the-counter medications are not fully guaranteed, especially when no thorough physical evaluation such as a diagnostic nasal endoscopy has been carried out prior to their use. They may not at all be useful as solitary therapy and additional medication may be required. Annoying side effects may preclude use or even cause substantial harm. They may also be totally unnecessary if oral medication prescribed by a doctor has been given.

Conclusion

Though there are intranasal drugs and delivery devices galore, including over-the-counter nasal saline and decongestant drops, none has been proved to have undisputed efficacy as a solitary treatment for the relief of nasal congestion and other symptoms of rhinitis. Additional oral medication may actually be responsible for bringing about relief. Large scale randomized studies of a similar kind might help to settle this question.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support and guidance of the Head of Department, Dr Mary Kurien, for carrying out this study.

Appendix 1: Study Questionnaire

Are you suffering from nasal block, dryness, runny nose, sneezing, loss of smell?

Do you also have fever, sore throat, cough, headache, body ache or malaise?

How long have you been suffering from these symptoms?

Have you taken any medication yet?

Are you also suffering from diabetes, hypertension, bronchial asthma or tuberculosis?

Have you had similar complaints in the past, for which you took medication?

Have you ever used nasal drops earlier for relief of such symptoms?

Have you experienced any discomfort from the use of such medications earlier?

How long have you used such medications during previous episodes?

Did you buy these medications yourself over the counter, or were you given a prescription?

Were you aware of these medications from media such as magazines and television?

Rate your symptomatic relief based on the scale below.

Speed at which you got relief (number of days after starting nasal drops).

Additional comments

Appendix 2: Details of Method of Random Allocation

The study protocol initially submitted required that an electronic randomization schedule be generated. This would mean that the bottles or dispensers containing the topical nasal preparations come pre-packaged, coded and labeled from the manufacturers. This would take more time besides being very complex to execute. Since the commercial or OTC (over the counter) preparations look almost the same except for the color difference, it was decided by the primary investigator (PI) that the bottles would be procured from the hospital pharmacy by internal indent, and coded in the department by a trusted staff member, and a nursing aide was appointed for the same.

To facilitate coding and to avoid drug expiry due to non-usage, it was decided that only 50 bottles including 25 each of the nasal saline or decongestant preparation would be procured as the first batch. This was subsequently increased to a batch size of 60 containing 30 bottles of each preparation, in order to simplify the process of counting and store-keeping. All the bottles were checked for the date of expiry and all were to expire after 2 years. The bottles were of plastic with an easily removable plastic label which could be stripped off both the faces of the bottle. All the bottles were then mixed up and shuffled in a large polythene bag. A bottle was taken at a time in random sequence. The labels were then pasted on a plain sheet of paper, with a number recorded next to the label and the same number written in permanent ink on the now bare bottle surface. This method was repeated for each bottle, with 10 bottles being labeled and coded per day until all 60 coded bottles were ready for use.

The sheets of paper containing the bottle numbers and other details were safely stored in a large paper envelop and remained sealed in the custody of the co-investigator till the end of the study. The bottles were then stored all together ready to be dispensed, again in random sequence. Each study subject was given a bottle at random from the above store set. Since subjects were recruited in consecutive order, the number of the bottle dispensed was recorded on the consent form and questionnaire pertaining to the subject.

Colleagues and co-workers were informed about the study details during a departmental presentation. Any patient complaining of nasal block, nasal congestion or nasal obstruction was selected as a study subject. Additional symptoms such as nasal discharge, sneezing, loss of smell, and dryness or crusting was taken into account, and the duration of symptoms and other details recorded. Presence of fever, sore throat or productive cough usually required additional medication but this decision was left to the individual consultants. All the subjects were given a topical nasal preparation which was either saline or decongestant. Anyone was allowed to prescribe antibiotics, anti-inflammatory or analgesic medication if deemed necessary, but oral antihistamines, steroids or mucolytics were strictly avoided as these might have a direct effect upon nasal congestion. Upon full recruitment of the initial batch size of 60 subjects, it was generally noticed that 4 subjects had an annoying headache, and 5 subjects had no relief at all. The 5 without any relief did not receive any kind of additional medication.

Appendix 3: Consort Checklist for Methodology

| Trial design | 3a | Parallel, prospective, randomized |

| 3b | Early termination due to adverse effects | |

| Participants | 4a | Patients suffering from nasal congestion and similar symptoms |

| 4b | Otorhinolaryngology Outpatient Department | |

| Interventions | 5 | Administration of nasal drops either saline or decongestant |

| Outcomes | 6a | Symptomatic relief of nasal congestion and similar symptoms |

| 6b | Adverse drug reaction noted in the form of headache | |

| Sample size | 7a | Sample size determined on the basis of previous studies |

| 7b | No interim analysis done | |

| Randomization | ||

| Sequence generation | 8a | Manual shuffling |

| 8b | Sequential allocation | |

| Allocation concealment mechanism | 9 | Labels changed on bottles and concealed till analysis |

| Implementation | 10 | Bottle(s) dispensed by primary investigator (PI) |

| Blinding | 11a | Double blinded- Patients and investigators blinded |

| 11b | Both preparations used are available over the counter and look similar | |

| Statistical methods | 12a | Chi square test to compare the saline and decongestant groups |

| 12b | Subgroup analysis for antibiotic use | |

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethics Approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institute Ethics Committee and the trial was registered with the Clinical Trials Registry- India, number REF/2016/10/012393 AU.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the study participants and their confidentiality has been ensured.

References

- 1.Prabhu V, Pandey A, Ingrams D. Comparing the efficacy of alkaline nasal douches versus decongestant nasal drops in postoperative care after septal surgery: a randomised single blinded clinical pilot study. Ind J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;63(2):159–164. doi: 10.1007/s12070-011-0231-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taverner D, Latte J. Nasal decongestants for the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;24(1):CD001953. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001953.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Low TH, Woods CM, Ullah S, Carney AS. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of normal saline, lactated Ringer’s, and hypertonic saline nasal irrigation solution after endoscopic sinus surgery. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2014;28(3):225–231. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2014.28.4031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harvey R, Hannan SA, Badia L, Scadding G. Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;18(3):006394. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006394.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egan M, Hickner J. Saline irrigation spells relief for sinusitis sufferers. J Fam Pract. 2009;58(1):29–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Price DD, Staud R, Robinson ME. How should we use the visual analogue scale (VAS) in rehabilitation outcomes? II: visual analogue scales as ratio scales: an alternative to the view of Kersten et al. J Rehabil Med. 2012;44(9):800–804. doi: 10.2340/16501977-1031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Damiani V, Camaioni A, Viti C, Scire AS, Morpurgo G, Gregori D. A single-centre, before-after study of the short- and long-term efficacy of Narivent in the treatment of nasal congestion. J Int Med Res. 2012;40:1931–1941. doi: 10.1177/030006051204000534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nsouli TM (2009) Long-term use of nasal irrigation: harmful or helpful? Am Acad Allergy Asthma Immunol Abstract O32

- 9.Tomooka LT, Murphy C, Davidson TM. Clinical study and literature review of nasal irrigation. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1189–1193. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200007000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Talbot AR, Herr TM, Parsons DS. Mucociliary clearance and buffered hypertonic saline solution. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:500–503. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199704000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anglen JO, Apostoles S, Christensen G, Gainor B. The efficacy of various irrigation solutions in removing slime-producing Staphylococcus. J Orthop Trauma. 1994;8:390–396. doi: 10.1097/00005131-199410000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adam P, Stiffman M, Blake RL. A clinical trial of hypertonic saline nasal spray in subjects with the common cold or rhinosinusits. Arch Fam Med. 1998;7:39–43. doi: 10.1001/archfami.7.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Georgitis JW. Nasal hyperthermia and simple irrigation for perennial rhinitis: changes in inflammatory mediators. Chest. 1994;106:1487–1492. doi: 10.1378/chest.106.5.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeiger R, Shatz M. Chronic rhinitis: a practical approach to diagnosis and treatment, II: treatment. Immunol Allergy Pract. 1982;4(3):26. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yerushalmi A, Lwoff A. Treatment of infectious coryza and persistent allergic rhinitis by thermotherapy [in French] C R Sceanes Acad Sci. 1980;291:957–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davidson TM, Murphy C. Rapid clinical evaluation of anosmia: the alcohol sniff test. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:591–594. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900060033005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferguson BJ. Allergic rhinitis: options for pharmacotherapy and immunotherapy. Postgrad Med. 1997;101:117–126. doi: 10.3810/pgm.1997.05.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mabry RL. Therapeutic agents in the medical management of rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1993;26(4):561–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]