Abstract

To determine Ethnic differences in the frequency of the relatively common anatomical variants along with difference in anatomy of sinonasal region with surgical importance. A study was conducted to determine the frequency of anatomical variants, volumes of paranasal sinuses using computed tomography and to identify any difference between Group A consisting of people of Indian subcontinent and Group B consisting of people from north east Asian region. Volumetric analysis done using cumulative of area multiplied by slice thickness. The results were compared using Chi square test, p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Among the common and uncommon anatomical variants (Agger nasi, pneumatized uncinate, concha bullosa etc.) there was no significant difference between the two groups. In both the groups Keros Type 1 was the most common type of ethmoid roof seen. On volumetric analysis sphenoid sinus volume was found to be higher in Indians without mongoloid features. Hence it’s ideal that in this era of endoscopic sinus surgery we tailor make approaches to address individual anatomical variation.

Keywords: Paranasal sinuses, Anatomic variation, Ethnic, CT-scan, Volumetric analysis

Introduction

“Remove only as much as necessary, Preserve as much as possible”—has been the dictum of Functional endoscopic sinus surgery—“Horst Ludwig Wullstein”. The anatomy of the nasal cavities and paranasal sinuses is probably the most varied in the human body [1]. Due to their complex three dimensional structure and many morphologic variations, understanding these anatomical aspects are of prime importance to a rhinology surgeon. Endoscopic sinus surgery is one of the prime components in the management of chronic rhinosinusitis. The incidence of these anatomic variations varies among different ethnic groups. This study aims to study these differences in different ethnic groups that could possibly aid an endoscopic sinus surgeon.

A key concept indulged in Endoscopic sinus surgery is that inflammatory sinus disease occurs due to impaired/deranged mucociliary drainage pathways of the sinuses into the ostiomeatal complex. FESS is aimed to restore this functional drainage of the mucociliary pathways [2]. A variety of anatomic variations in the ostiomeatal complex can predispose to maxillary, ethmoid, frontal and sphenoid sinus disease, although its etiological role is still debatable. In Functional endoscopic sinus surgery, very minor manipulation of these key sites in the lateral nasal wall helps to resolve enormous pathologies in the sinuses [3, 4].

In the past decade, CT of the nose and paranasal sinuses has become a roadmap for an endoscopic sinus surgeon, as it provides excellent bone detail which is of prime importance to the surgeon. The primary aim of radiology is not only to delineate the extent of disease but also to enlighten the anatomical bony detail with thorough detail in certain key areas along with their variations. CT is the radiological imaging modality of choice in chronic rhino-sinusitis (CRS) and preoperative planning for functional endoscopic sinus surgery (FESS) [3].

Yeoh et al. proposed higher incidence of exposure of optic via the Onodi cells in Asian population than in Caucasian population, therefore can anatomical variations in ethnic groups play a part in planning for endoscopic sinus surgery, and is something to be given a thought.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted by the department of ENT and Head and Neck Surgery and department of Radiology, Kasturba Medical College, Manipal University, Manipal. It was a retrospective study done over a period of 2 years from September 2015 to August 2017. The study group consists of two groups, 44 patients in group A and 20 in group B belonging to different racial populations. Group A consists of patients from southern India. Group B consists of patients from northeast India with mongoloid features. Power factor was calculated and applied to the study by the statician.

CT scan of nose and paranasal sinuses was taken using a 64 slice Philips Spiral CT scanner. Consecutive Computed tomographic scans were acquired in the axial plane without IV contrast. The coronal and sagittal images were reconstructed. The images were collimated to 3 mm slice thickness. The data collected after the imaging is done, and were tabulated in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Data was then exported to SPSS, version 15.0 for statistical analysis. p Value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

All patients who underwent CT scan of nose and paranasal sinuses for symptoms suggestive of chronic rhinosinusitis, allergic rhinosinusitis, vasomotor rhinitis, any patient with symptomatic upper respiratory pathology were included. Patients with previous facial trauma, previous sinus surgeries, paranasal sinus malignancies, gross polypoidal disease of the sinuses obscuring study of subtle anatomic details, congenital facial anomalies were excluded from the study. Specific observations regarding presence of anatomical variants of the ostiomeatal complex and paranasal sinuses, presence of other important anatomical landmarks and variations like Aggernasi, Haller cells, Supra orbital cells, Onodi cells, lamina papyracea etc., assessment of volumes of sinuses. (Cumulative of area of sinus x slice thickness for each sinus) were done.

Technique of Measurement of Certain Parameters

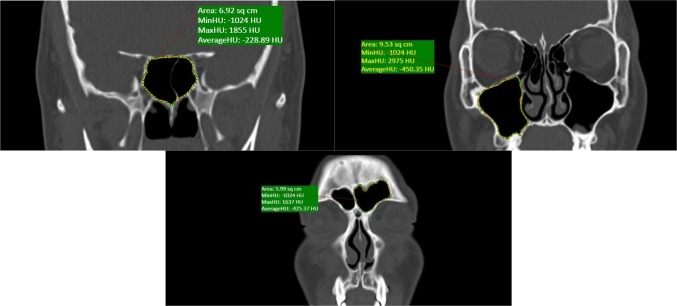

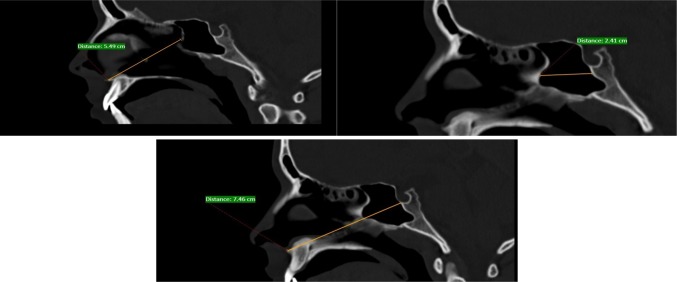

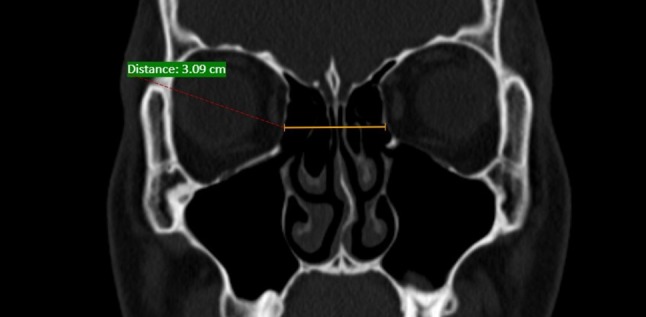

Figures 1, 2, 3, 4 and Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Measurement of sinus volumes

Fig. 2.

Inter-laminar distance (between lamina and lamina). It is taken at level of bulla where lamina forms the lateral wall

Fig. 3.

Measurement of distance from anterior nasal spine to anterior and posterior wall of sphenoid and distance between anterior and posterior wall of sphenoid

Fig. 4.

Depth of cribriform plate. It is taken from medial end of fovea ethmoidalis up to lateral end of cribriform plate

Table 1.

Keros classification of the two groups

| Our study | Group A | Group B | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Left | Right | Left | |

| Keros Type 1 | 70% | 77% | 60% | 50% |

| Keros Type 2 | 30% | 23% | 40% | 50% |

| Keros Type 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Observations and Results

The mean age in group A was 32.4 years, while in group B was 22.3 years. Distribution of sex was similar in both the groups. Tables 2 and 3 shows comparison between the two groups. Among the commonest anatomical variations pneumatized Agger nasi is found to be the commonest in both groups A and B (85% both unilateral and bilateral). Pneumatized middle turbinate (concha bullosa) was the second most common variation in both groups A and B (64% and 52% respectively) but did not show any statistical significance. The incidence of paradoxically curved middle turbinate was found to be 6% and 7% in groups A and B respectively. The superior attachment of Uncinate process was evaluated and found to be attached to Lamina papyracea in 70% in both groups A and B.

Table 2.

Comparison of sinonasal anatomy of the two groups

| Parameter | Group A | Group B | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumatised Agger nasi | 37 | 17 | 0.87 |

| Concha bullosa | 57 | 21 | 0.45 |

| Paradoxically curved middle turbinate | 5 | 3 | 0.78 |

| Superior attachment of uncinate process to middle turbinate | 15 | 6 | |

| Superior attachment of uncinate process to skull base | 11 | 6 | |

| Superior attachment of uncinate process to lamina papyracea | 62 | 28 | |

| Pneumatised uncinate process | 2 | 2 | 0.49 |

| Medialized uncinate process | 7 | 5 | 0.60 |

| Lateralized uncinate process | 1 | 1 | 0.40 |

| Dehiscent lamina payracea | 4 | 2 | 0.68 |

| Distance between lamina to opposite lamina | 2.71 (cm) | 2.66 (cm) | 0.78 |

| Anterior nasal spine to anterior wall of sphenoid | 5.54 (cm) | 5.31 (cm) | 0.52 |

| Anterior nasal spine to posterior wall of sphenoid | 8.16 (cm) | 7.68 (cm) | 0.60 |

| Haller cells | 13 | 3 | 0.93 |

| Onodi cells | 7 | 3 | 0.75 |

| Exposure of > 50% of ICA | 2 | 1 | 0.63 |

| Exposure of > 50% of optic nerve | 6 | 3 | 0.55 |

| Suprabullar cells | 46 | 11 | |

| Interfrontal septal cell | 3 | 1 | 0.60 |

Table 3.

Frontal anatomy & Volumetric analysis of the two groups

| Parameter | Group A | Group B | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Left | p value | Right | Left | p value | |

| Type 1 frontal cells | 12 | 15 | 4 | 7 | ||

| Type 2 frontal cells | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | ||

| Type 3 frontal cells | 1 | 3 | – | – | ||

| Type 4 frontal cells | 1 | – | – | – | ||

| Keros 1 | 31 | 34 | 12 | 10 | ||

| Keros 2 | 13 | 10 | 8 | 10 | ||

| Keros 3 | – | – | – | – | ||

| Slope of skull base (degree) | 17 | 17.2 | 0.82 | 16.8 | 17.1 | 0.66 |

| Orbital height (cm) | 3.73 | 3.76 | 0.39 | 3.59 | 3.54 | 0.75 |

| Height of maxillary sinus: height of skull base | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.76 | ||

| Frontal sinus ostium diameter (cm) | 4.92 | 3.91 | 0.45 | 4.21 | 3.97 | 0.38 |

| Volume of maxillary sinus (cm3) | 7.59 | 8.45 | 7.22 | 8.31 | ||

| Volume of frontal sinus (cm3) | 2.2 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 2.3 | ||

| Volume of sphenoid sinus (cm3) | 5.5 | 4.63 | 0.028 | |||

Pneumatized Uncinate process was found in more commonly in group B (2% and 5% respectively). Similarly dehiscence of lamina papyracea was found commonly in group B (2.5% and 5% of the patients in group A and B respectively). In our study, on right side, Kuhn frontal cells Type 1 was seen in 27%, Type 2 in 9%, Type 3 and Type 4 in 2% of the patients in group A. In group B, Type 1 were seen in 20% and Type 2 in 10%. Type 3 and 4 were not seen. On left side, Kuhn frontal cells Type 1 was seen in 34%, Type 2 in 9%, Type 3 in 7% in group A. In group B, Type 1 was seen in 35% and Type 2 in 10%. Type 3 and 4 was not seen on left in any of the patients.

In our study, Onodi cells were found in 8% of the patients in group A and 5% of them had bilateral Onodi cells. In group B, 7.5% of patients had Onodi cells out of which 5% had unilateral. In our study bulging of Internal carotid artery in the lateral wall of sphenoid sinus was encountered in two cases in group A and one in group B of. Similarly we have seen 6 cases of protrusion of optic nerve into the postero-lateral wall of sphenoid sinus in group A and 3 in group B. Only those with greater than 50% protrusion were taken into consideration.

In our study, we have considered the volumes of sinuses independently considering its importance in unilateral pathologies, In group A the average right maxillary sinus volume was found to be 7.59 cc and left maxillary sinus volume 8.45 cc. The average right frontal sinus volume was found to be 2.2 cc and left frontal sinus volume 2.8 cc. Average sphenoid sinus volume was found to be 5.5 cc. In group B average right maxillary sinus volume was found to be 7.22 cc and left maxillary sinus 8.31 cc. Average frontal sinus volumes on both sides were 2.3 cc. Average sphenoid sinus volume was 4.69 cc.

In our study the average frontal sinus ostium diameter on right side was 4.92 mm and 4.21 mm in group A and B respectively. On the left side 3.91 mm and 3.97 mm in group A and group B respectively. Suprabullar cells were more common in group A (50%,) compared to 25% in group B. No Supraethmoidal cells were found in our study.

Discussion

The superiority of CT over plain radiographs has been described by the Royal college of Radiologists in routine management of chronic rhinosinusitis [5]. Computed tomography is now the investigation of choice, especially for patients who are planned for an endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS), enabling the rhinologist to understand the varied anatomy pertaining to the paranasal sinus region. Thus it is truthfully described as “ROAD MAP OF FESS”.

Table 4 shows the prevalence of the common anatomical variants detected on CT imaging in various studies [5]. Many studies have been done to identify the etiological role of anatomical variations of the paranasal sinus region in the pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusistis, but their role in it is still debatable. This is mainly because all these studies compared normal people to people with chronic rhinosinusitis and found no difference in the incidence of anatomical variants.

Table 4.

Incidence of anatomic variants of paranasal sinuses demonstrated on CT Scan in the published series [5]

| Jones | Bolger et al. | Clark | Calhoun | Kennedy | Tonai and Baba | Willner | Arslan | Danese | Lloyd | Basic | Kayalioglu | Perez-pinas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concha bullosa | 18–23% | 50–53% | 11–33% | 16–29% | 36% | 11–13% | 30% | 31% | 14–24% | 27–29% | 34% | ||

| Paradoxical middle turbinate | 7–16% | 22–27% | 12–15% | 15% | 11–30% | 7–16% | 15–17% | 27% | |||||

| Bent uncinate | 2–6% | 3% | 31% | 16–21% | 7–12% | ||||||||

| Pneumatized uncinate | 0–3% | 2–5% | 0.4% | 21–26% | 2% | ||||||||

| Agger nasi cells | 96% | 86–89% | 16–24% | 5–8% | |||||||||

| Infra-orbital cells (Haller) | 6–12% | 41–46% | 10% | 33–39% | 23–28% | 6% | 34% | 21% | 4–5% | 3% | |||

| Spheno-ethmoidal cells (Onodi cells) | 7–9% | 12% | 10% | 11% | |||||||||

| Septal deviation | 24% | 20–40% | 21% | 36% | 33–42% | 12–22% | 55% |

Yeoh et al. based on his small number of cadaveric dissections, suggested significant amount of difference among variations of paranasal sinus anatomy between Chinese and Caucasian populations [6]. Any operating surgeon should have a thorough understanding, keeping in mind the grave dangers that can occur while operating in this region.

The incidence of Concha bullosa ranges between 4 and 80% in different studies. These discrepancies in the incidence may depend on the criteria of pneumatization of different researchers and on the method of analysis. Some researchers accept very small and physiologically insignificant conchae as conchae bullosa. In our study, we found that Concha bullosa was present in 64% and 52% of patients in group A and group B respectively, which is comparable to a study done by Bolger et al. who observed this variation in 50–53% of the popultaion [7] and a study done by G.A.S Lloyd and V J Lund who found Concha bullosa in 24% [8]. Other studies like Perez et al. found it in 24.5% patients [9] and Adeel et al. in 18.2% patients [10].

Other common variants like superior attachment of uncinate process and pneumatization of uncinate process where found to be comparable when compared to similar studies like Prof Min et al. [11] and Bolger et al. [7] respectively. Similar results where observed with, paradoxically curved middle turbinate which is similar to a study done by Lloyd et al. [8] and Tonai and Baba [12]. Moulin et al. found dehiscent lamina papyracea in 6 patients in a study group of 783 patients which is similar to our study [13].

Several studies have been done to identify the differences in distribution of frontal cells and agger nasi. Our study shows similar results to those done by Lien et al. [14], Han et al. [15]. Lee et al. [16] in his study on Caucasian population ha shown slightly higher incidence of Type 1 frontal cells (Table 5).

Table 5.

Agger Nasi and Frontal cell variants-comparision of various studies

Keros divided the ethmoid roof into three types based on the depth of cribriform plate from ethmoid roof. His study included CT scans of 350 Germans. Type 1: 1–3 mm; Type 2: 4–7 mm; Type 3: 8–16 mm. Keros described that the skull base is at danger to be damaged during ESS and Type 3 with its low lying cribriform plate is particularly vulnerable. Table 6 shows various studies on the type ethmoid roof. Our study showed Type I keros to be more common in both the groups which is contradicting other studies. Keros Type III cases were not seen in our study.

Table 6.

Keros classification in various studies

Previous Studies

According to Mason et al., Onodi cells are best seen in Coronal view, as the maxillary sinus can encroach upon superiorly and mimic the appearance of an Onodi cell [23]. Driben et al. [24] concluded that Onodi is sometimes not picked up on a CT scan, hence should be assessed carefully while dealing with the sphenoethmoid region. In our study, the prevalence of Onodi cells was found to be similar in both the groups and comparable to other studies done by Perez Pinas et al. [9]. Similarly the prevalence of haller cells also did not show any significant difference.

Yeoh and Tan [6] described that there could be a higher chance of protrusion of optic nerve in the lateral wall of sphenoid sinus in Asians, but we found no difference between the groups.

Volumetric analysis can be used for objectively used for defining of hypoplasia and atelectasis [25]. In a study of volumetric analysis done by Cohen et al. [26], he found that the volume of the maxillary sinus was the largest (12.75 ± 4.38 cc) followed by the sphenoid (4.00 ± 1.99 cc) and frontal (2.92 ± 2.57 cc). Table 7 shows previous studies on volumetric analysis.

Table 7.

Studies on volumetric analysis

Previous Studies on Volumetric Analysis

In our study, we have considered the volumes of sinuses independently considering its validity in unilateral pathologies. Sphenoid sinus volumes difference was found to be statistically significant, rest of the sinuses showed no difference. We have encountered two cases of incompletely pneumatized left frontal sinus in group A. Both of these patients were below 10 years.

Lien et al. [14] in his study of anatomy of frontal recess identified the complex nature of it and the role played by Suprabullar(SBC), Supraethmoidal (SEC) cells and recess terminalis (RT) in causing frontal sinusitis. He demonstrated the affect of these cells in the diameter of frontal ostium. He concluded that Frontal bullar cells caused more narrowing of the frontal ostium than SBC’s and SEC’s. Therefore the diameter which ranged 6.6–7 mm, in presence of frontal bullar cells came down to 3.8 mm. In our study the average frontal sinus ostium diameter was significantly less but did not show any statistically significant difference. We found no Supraethmoidal cells in our study.

The slope of skull base determines the risk of damage to dura which can lead to csf leak. Dessi et al. [31] reported that when the asymmetry of the skull base is present it is usually more on the right side. We could not identify any statistically significant difference among the two sides in our study.

Conclusion

Variation in paranasal sinus anatomy is often encountered and must be taken into consideration when operating on various ethnic groups in India. Hence prior to Endoscopic sinus surgery, it becomes imperial for the operating surgeon to understand the anatomy and its variations in the region of paranasal sinuses. Computer tomography is an efficient tool in providing a detailed depiction of paranasal sinus anatomy necessary for a surgeon, and with the advent of intra-op imaging and navigation CT has become a surgeon’s invaluable tool for the management of chronic rhino-sinusitis. Although Keros Type 1 was the most common ethmoid roof seen in our study and statistically significant sphenoid sinus volume difference among the two groups, the current study does not show any other significant anatomical variations. However, considering the wide range of possible variations in the anatomy of this region each case should be evaluated individually in order to avoid any dreadful complications, hence maximize patient’s benefits.

Limitations of the Study

Small sample size in each study group. A study of this type requires about 200 subjects in each group. Better methods of volumetric analysis of the paranasal sinuses are presently available with three dimensional reconstruction of CT being available. It was not used in our study due to financial aspects of the patients being taken into consideration.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Approval from institutional ethical committee.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Venkata Joga Prasanth Mokhasanavisu, Email: jogaprasanth@gmail.com.

Rohit Singh, Email: rohit.singh.dr@gmail.com.

R. Balakrishnan, Email: baluent@gmail.com

Rajagopal Kadavigere, Email: rajagopal.kv@manipal.edu.

References

- 1.Rowe Jones J, Mackay I, Colguhoun I. Charing cross CT protocol for endoscopic sinus surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1995;109(11):1057–1060. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100132013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang L, Han D, Ge W, Tao J, Wang X, Li Y, Zhou B. Computed tomographic and endoscopic analysis of supraorbital ethmoid cells. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(4):562–568. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stammberger H. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery: the Messerklinger technique. Philadelphia: B.C. Decker; 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolf G, Anderhuber W, Kuhn F. Development of the paranasal sinuses in children: implications for paranasal sinus surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102(9):705–711. doi: 10.1177/000348949310200911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Badia L, Lund VJ, Wei W. Ethnic variation in sinonasal anatomy on CT scanning. Rhinology. 2005;43:210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yeoh KH, Tan KK. The optic nerve in the posterior ethmoid in Asians. Acta Otolaryngol (Stockh) 1994;114:329–336. doi: 10.3109/00016489409126065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolger WE, Butzin CA, Parsons DS. Paranasal sinus bony anatomic variations and mucosal abnormalities: CT Analysis for endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:56–64. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lloyd GA, Lund VJ, Scadding GK. CT of the paranasal sinuses and functional endoscopic surgery: a critical analysis of 100 symptomatic patients. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105(3):181–185. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100115300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perez Pinas I, Sabate J, Carmona A, Catalina-Herrera CJ, Jiménez-Castellanos J. Anatomical variations in the human paranasal sinus region studied by CT. J Anat. 2000;197:221–227. doi: 10.1017/S0021878299006500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adeel M, Rajput MS, Akhter S, Ikram M, Arain A, Khattak YJ. Anatomical variantions of nose and paranasal sinuses; CT scan review. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013;63(3):317–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Min Y-G, Koh T-Y, Rhee C-S, Han M-H. Clinical implications of the uncinate process in paranasal sinusitis: radiologic evaluation. Am J Rhinol. 1995;9(3):131–135. doi: 10.2500/105065895781873782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonai A, Baba S. Anatomic variations of the bone in sinonasal CT. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1996;525:9–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moulin G, Dessi P, Chagnaud C, et al. Dehiscence of the lamina papyracea of the ethmoid bone: CT findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15(1):151–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lien C-F, Weng H-H, Chang Y-C, Lin Y-C, Wang W-H. Computed Tomographic analysis of frontal recess anatomy and its effect on the development of frontal sinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2010;120:2521–2527. doi: 10.1002/lary.20977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han D, Zhang L, Ge W, Tao J, Xian J, Zhou B. Multiplanar computed tomographic analyisis of the frontal recess region in Chinese subjects without frontal sinus disease symptoms. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2008;70(2):104–112. doi: 10.1159/000114533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee WT, Kuhn FA, Citardi MJ. 3D computed tomographic analysis of frontal recess anatomy in patients without frontal sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;131(3):164–173. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chow JM, Mafee MF. Radiological assessment preoperative to endoscopic sinus surgery. Otolaryngolclin North Am. 1989;22(4):691–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderhuber W, Walch C, Fock C. Configuration of ethmoid roof in children 0Y14 years of age. Laryngorhinootologie. 2001;80:509–511. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Souza SA, Souza MMA, Idagawa M, et al. Computed tomography assessment of the ethmoid roof: a relevant region at risk in endoscopic sinus surgery. Radiol Bras. 2008;41:143–147. doi: 10.1590/S0100-39842008000300003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paber J, Cabato M, Villarta R. Hernandez J radiographic analysis of the Ethmoid roof based on KEROS classification among Filipinos. Philipp J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;23(1):15–19. doi: 10.32412/pjohns.v23i1.763. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sahin C, Yılmaz Y, Titiz A, et al. Türk Toplumunda Etmoid C, atı ve Kafa Tabanı Analizi. KBB ve BBC Dergisi. 2007;15:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Basak S, Akdilli A, Karaman CZ, et al. Assessment of some important anatomical variations and dangerous areas of the paranasal sinuses by computed tomography in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000;55:81–89. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5876(00)00362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason JD, Jones NS, Hughes RJ, Holland IM. A systematic approach to the interpretation of computed tomography scans prior to endoscopic sinus surgery. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112(10):986–990. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100142276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Driben JS, Bolger WE, Robles HA, et al. The reliability of computerized tomographic detection of the Onodi (Spheno-ethmoid) cell. Am J Rhinol. 1998;12:105–111. doi: 10.2500/105065898781390325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Emirzeoglu M, Sahin B, Bilgic S, Celebi M, Uzun A. Volumetric evaluation of the paranasal sinuses in normal subjects using computer tomography images: a stereological study. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen O, Warman M, Fried M, Shoffel-Havakuk H, Adi M, Halperin D, Lahav Y. Auris, nasus, larynx Volumetric analysis of the maxillary, sphenoid and frontal sinuses: a comparative computerized tomography based study. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45(1):96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawarai Y, Fukushima K, Ogawa T, Nishizaki K, Gunduz M, Fujimoto M, et al. Volume quantification of healthy paranasal cavity by threedimensional CT imaging. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1999;540:45–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yonetsu K, Watanabe M, Nakamura T. Age-related expansion and reduction in aeration of the sphenoid sinus: volume assessment by helical CT scanning. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2000;21:179–182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fernandes CL. Volumetric analysis of maxillary sinuses of Zulu and European crania by helical, multislice computed tomography. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118(11):877–881. doi: 10.1258/0022215042703705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park IH, Song JS, Choi H, Kim TH, Hoon S, Lee SH, et al. Volumetric study in the development of paranasal sinuses by CT imaging in Asian: a pilot study. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74:1347–1350. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dessi P, Castro F, Triglia JM, et al. Major complications of sinus surgery: a review of 1192 procedures. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:212–215. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100126325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]