Abstract

Branchial arch anomalies are the most common congenital neck masses. The second branchial arch anomalies followed by first arch anomalies are seen commonly in the descending order. They originate from remnants of branchial arches and clefts. They may present as cysts, sinus tracts, fistulae or cartilaginous remnants. They are mostly located in the lateral aspect of the neck anterior to the sternocleidomastoid, anterior to the hyoid bone, preauricular region or at the angle of the mandible. A complete fistula communicating with a branchial arch cyst is a very rare congenital anomaly of the branchial apparatus. These patients are generally asymptomatic but may present with mucoid discharge from the tract. Here we present a case of branchial fistula associated with a branchial cyst in a 11 year old child.

Keywords: Branchial arches, Branchial cleft cyst, Branchial cleft sinus, Sternocleidomastoid

Introduction

Branchial arch anomalies represent embryological precursors of the face, neck and pharynx. These anomalies comprise 17% of the pediatric cervical masses. Six pairs of branchial arches are formed in cranio-caudal succession on either side of the pharyngeal foregut. Of the six branchial arches, the second arch anomalies are most common followed by the first arch [1, 2]. The fifth arch anomalies do not exist as the fifth cleft does not take part in the formation of cervical sinus of His. The classical location is in the lateral aspect of the neck above the hyoid bone and anterior to sternocleidomastoid muscle. These anomalies mostly present as cysts, sinus tracts, fistulae and cartilaginous remnants or in combination with typical radiological findings depending on the arch involved. We present an unusual association of branchial fistula associated with a branchial cyst in a young girl with the imaging characteristics.

Case Report

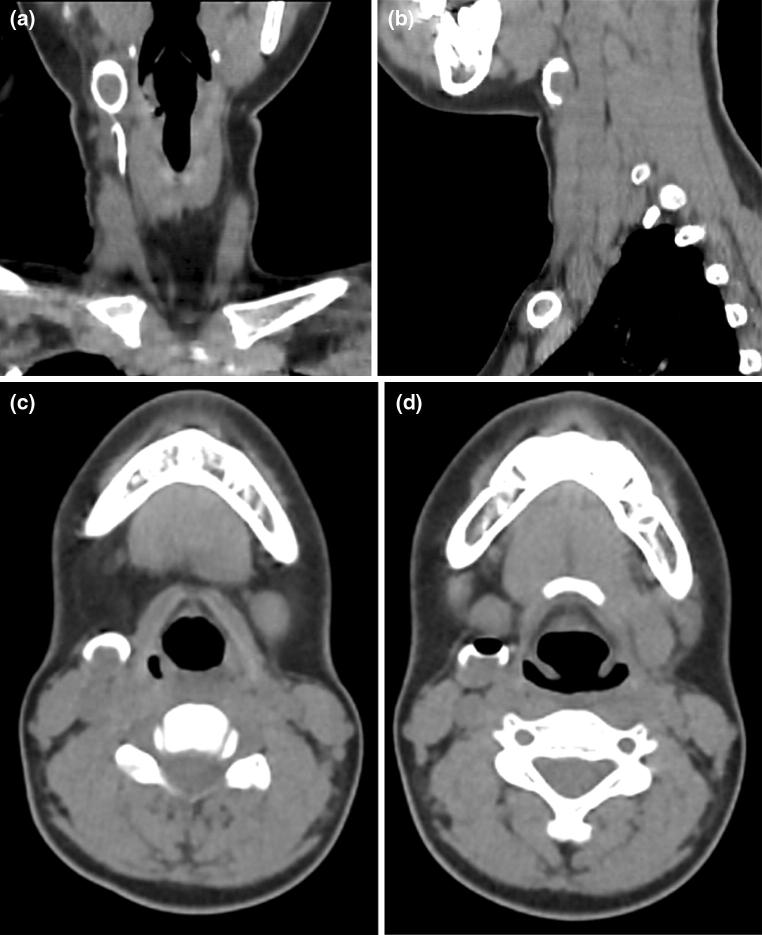

A 11 year girl presented with history of discharge from a tiny spot on the right side of the neck on and off since birth. There is no history of trauma or surgical intervention. Local examination revealed a small punctum on right side of neck on the medial border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and lateral to right thyroid lobe. Thin watery fluid was oozing on pressure over the region. There was no sign of inflammation around the opening. CT sinography was performed to delineate the exact course of tract before surgery. Coronal and sagittal reformatted images revealed a contrast filled tract coursing anterior to right of sternocleidomastoid muscle and ending into the branchial cyst. The opacified cyst was crescentic in shape anteriorly showing a rounded unfilled isodense oval area in the dependent portion (Fig. 1). The isodense solid component of the cyst may be due to inspissated secretions lying in the dependent region. An air pocket was noted gravitating superiorly which was introduced inadvertently. These features were demonstrsated in 3D reformation as a concavo convex density (Fig. 2). Based on the imaging and clinical history, a diagnosis of branchial fistula in association with branchial cyst of second arch was considered. The patient underwent excision of the tract by a step ladder approach.

Fig. 1.

a–d CT scan sagittal and coronal views. a Coronal view shows Gd-DTPA opacified course of the branchial sinus tract. b, c Sagittal and axial views reveal the curvilinear branchial cyst with the dependent solid component. d Inadvertent introduction of air pocket is seen within the cyst

Fig. 2.

CT scan 3D reformation. Both tract of the fistula and cyst are demonstrated. The hollow circular area is due to the air pocket within the cyst

Discussion

Branchial cleft cysts occur in adolescene around 20–40 years with slight male preponderance usually affecting the left side while fistulae are seen in infants and young children showing communication with two epithealized surfaces. Fistulae are classically located in the mid or lower third of the neck with an external opening anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. It may traverse between the internal and external carotid arteries and enter into the pharyngeal space. Branchial cleft sinus communicates with skin and a communication with pharynx is called a branchial pouch sinus. The branchial apparatus comprises of five mesodermal arches separated by ectodermal clefts. The common anomalies of the branchial apparatus include cyst, sinus, fistula and cartilaginous remnants in decreasing order. Von Baer first described the branchial apparatus while its anomalies were first described by Von Ascheroni [3]. Of the six branchial arches the most common anomalies arise from the second branchial arch comprising 90–95% followed by first arch representing up to 1–4%. During 4–7th gestation, the second arch grows caudally and covers the 3, 4 and 6th arches leading to formation of cervical sinus of His with the epipericardial ridge of the fifth arch. The ends of the sinus fuse and no defects are seen. The most common theory accepted was an incomplete obliteration of the branchial arch cleft or buried epithelial cells [4, 5]. Amot’s Type 1 cyst/sinus lies in the parotid gland lined by squamous epithelium mostly seen in adolescence. Type 2 defect is seen in the anterior triangle of neck showing a communicating tract up to the external auditory canal. This defect is seen mostly in childhood. Bailey classified the second branchial cleft cysts into 4 subtypes, the first two types with respect to anteroposterior relation to sternocleidomastoid muscle. The more common type II cyst runs posterior to the submandibular gland. Type III runs along the lateral pharyngeal wall between the internal and external carotid arteries while Type IV arises from the pharyngeal mucosal space [6]. According to Kings criteria, any cyst that arises away from midline of the neck with lymphoepithelial features should be considered as a branchial cyst [7, 8]. A branchial cleft cyst is usually soft, well circumscribed, thin walled painless fluctuant mass measuring 1–10 cm in diameter often in association with upper respiratory tract infection or pregnancy. Infected cyst is tender and shows increase in size displacing the carotid and internal jugular vein causing dysphagia, dyspnea and dysphonia [9]. Infection, repeated surgeries and biopsies may be the stimuli for carcinogenesis [12–14]. Mucoid discharge in the anterior aspect of neck is the common symptom associated in majority of the cases. Abscess formation is well known following infection. On intravenous contrast administration the wall shows moderate enhancement. Canulation of the discharging punctum and radiography show the opacified tract and also the cyst if communication exists. CT scan is extremely useful in providing information about the relation of the fistulous tract with major neck vessels and in classifying for the management. Solidification of the cystic fluid and thickened wall following infection appear muddy showing heterogeneous hyperdensites on CT scan. Hemorrhagic cysts appear hyperdense on CT scan. Hypointense clear fluid in a cyst on T1 weighted MR imaging shows hyperintensity in T2 weighted sequence. Due to turbidity of fluid in the cyst is not always clear and T1 relaxation time may be shortened due to rich protein or mucoid content or hemorrhage giving a T1 hyperintense appearance [10, 11]. GRE images demonstrate blooming within the cyst due to altered blood components following hemorrhage. Branchial cleft cysts rarely undergo malignant transformation. Tracing of the entire fistulous tract is very difficult on imaging and fistulography is necessary to delineate the track by injection of iodinated contrast into the tract using a multidetector CT scanner. Solid/semisolid component of the cyst was well demonstrated in our patient. At CT fistulography, a note of importance in our patient is that Gadolinium 1 ml, instead of iodinated non-ionic contrast medium injected into sinus tract opacified the tract due to CT attenuation. The K-edge of gadolinium is close to the peak of CT spectrum and hence the marked absorption of X-ray beam of CT scanner. Administration of saline or dilute Gd-DTPA using a fine canula demonstrates the tract better. FIESTA sequence alone would show the tract equally well. Surgical excision through trans cervical approach either by step ladder or longitudinal incision and combined pull through technique is the treatment of choice. Two incisions are given with the higher incision larger than the lower to protect the neurovascular structures adjacent to the tract. The external approach alone may lead to recurrence of the tract due to incomplete excision compared to the combined approach [2].

References

- 1.Adams A, Mankad K, Offiah C, Childs L. Branchial cleft anomalies: a pictorial review of embryological development and spectrum of imaging findings. Insights Imaging. 2016;7:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s13244-015-0454-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford GR, Balakrishnan A, Evans JN, et al. Branchial cleft and pouch anomalies. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106:137–143. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100118900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De PR, Mikhail T. A combined approach excision of branchial fistula. J Laryngo Otol. 1995;109:999–1000. doi: 10.1017/S002221510013186X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.MaranAGD Buchanan DR. Branchial cysts, sinuses and fistulae. Clin Otolaryngol. 1978;3:77–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1978.tb00670.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liston SL, Siegel LG. Branchial cysts, sinuses, and fistula. Ear Nose Throat J. 1979;58:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey H. The clinical aspects of branchial cysts. Br J Surg. 1933;10:173–182. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800218202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sinha D, Utture SK (2011) Branchial cysts: a case report of a benign lymphoepithelial cyst in the Neck with review of literature. Bombay Hosp J 43(3). https://www.bhj.org.in/journal/2001_4303_july01/case_415.htm

- 8.Bhanote M, Yang GC. Malignant first branchial cleft cysts presented as submandibular abscesses in fine needle aspiration: report of three cases and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol. 2008;36:876–881. doi: 10.1002/dc.20920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee HJ, Kim EK, Hong S. Sonographic detection of intrathyroidal branchial cleft cyst: a case report. Korean J Radiol. 2006;7:149–151. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2006.7.2.149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shin JH, Lee HK, Kim SY, et al. Parapharyngeal second brachial cyst manifesting as cranial nerve palsies: MR fndings. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:510–512. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cerezal L, Morales C, Abascal F, et al. Pharyngeal branchial cyst: magnetic resonance fndings. Eur J Radiol. 1998;29:1–3. doi: 10.1016/S0720-048X(97)00183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernstein A, Scardino PT, Tomaszewki MM, Cohen MH. Carcinoma arising in a branchial cleft cyst. Cancer. 1976;37:2417–2422. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197605)37:5<2417::AID-CNCR2820370534>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho JS, Shin SH, Kim HK, et al. Primary papillary carcinoma originated from a branchial cleft cyst. J Korean Surg Soc. 2011;81(Suppl 1):S12–S16. doi: 10.4174/jkss.2011.81.Suppl1.S12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Girvigian MR, Rechdouni AK, Zeger GD, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a second branchial cleft cyst. Am J Clin Oncol. 2004;27:96–100. doi: 10.1097/01.coc.0000047127.46594.C0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]