One in five physicians has experienced sexual harassment by patients.1 The 2018 National Academy of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) report on sexual harassment highlights the burden of patient-perpetrated sexual harassment, and calls for clear institutional policies to combat this in order to foster culture change.2

Despite the prevalence of patient-perpetrated sexual harassment and guidance from the NASEM report, it remains unknown to what extent graduate medical education (GME) training programs maintain policies and guidance that address patient-perpetrated sexual harassment.

METHODS

Following IRB approval, we conducted a web-based survey of designated institutional officials (DIO) at the top 20 US hospitals as identified by US News and World Report “Best Hospital” rankings in 2017.3 Weekly reminder emails were sent for one month with subsequent letters and phone calls (maximum of three telephone calls) to nonresponding DIOs. Two hospitals shared a DIO, resulting in a sample size of 19 institutions.

Drawing on the UK General Medical Council and the American Medical Association definitions, we operationalized sexual harassment as “unwelcomed attention or behavior of a sexual nature that might be offensive or cause a person to feel unsafe and uncomfortable.”4 Officials were asked whether they (1) maintained a general sexual harassment policy; (2) offered training for responding to sexual harassment; (3) maintained a policy addressing patient-perpetrated sexual harassment; (4) offered training for responding to patient-perpetrated sexual harassment; (5) had a protocol for reporting patient-perpetrated sexual harassment; and (6) if patient-perpetrated sexual harassment was a problem in their GME programs.

In addition, two investigators (EMV and ALO) independently reviewed all submitted and publicly available GME policies for each hospital. Differences in review of the policies were discussed until the investigators reached consensus.

RESULTS

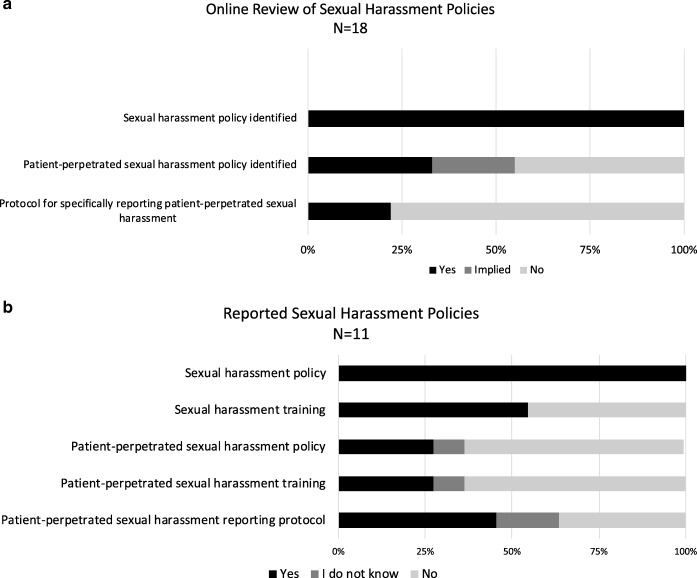

The DIOs surveyed oversee approximately 25,000 residents and fellows. Of the 19 DIOs contacted, 14 responded to question one and endorsed having a sexual harassment policy. Eleven completed the survey. Six of the 11 (54.5%) responders reported providing sexual harassment training, while only three of the 11 (27.3%) reported policies on patient-perpetrated sexual harassment with associated training. Six of the 11 (54.5%) responders reported patient-perpetrated sexual harassment was a problem at their GME program (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Sexual harassment and patient-perpetrated sexual harassment policies and protocols. a The presence of sexual harassment and patient-perpetrated sexual harassment policies, training, and protocols as reported by DIOs. b Review of sexual harassment and patient-perpetrated sexual harassment policies and protocols. The label “implied” refers to policies in which the harasser was not considered a supervisor or colleague but a third party or visitor, and “patient” was never directly mentioned. Figure 1 contains poor-quality text inside the artwork. Please do not re-use the file that we have rejected or attempt to increase its resolution and re-save. It is originally poor; therefore, increasing the resolution will not solve the quality problem. We suggest that you provide us the original format. We prefer replacement figures containing vector/editable objects rather than embedded images. Preferred file formats are .eps, .ai, .tiff, and .pdf. Also, please check if Figure 1 is correctly captured.Figure 1 is correctly captured. I was unaware the submitted images were not accetable. I have attached the original file of the images as requested.

Sexual harassment policies were available online for 18 institutions and were independently reviewed. All 18 policies defined sexual harassment consistent with our definition. Ten programs maintained policies that implied the inclusion of patient-perpetrated sexual harassment in their definition, of which six policies specifically addressed patient-perpetrated sexual harassment. Only four of the policies included a reporting process within the policy. Of those, only one provided clear guidance on how to effectively address the behavior and clinical needs of the patient (Fig. 1b).

DISCUSSION

Patient-perpetrated sexual harassment is an identified issue for residents and fellows4 and contributes to physician burnout.5 Despite this, only six of the 18 institutions whose policies were reviewed online had specifically addressed patient-perpetrated sexual harassment and only one included direction for reporting the patient while continuing clinical care. Patient-perpetrated sexual harassment warrants distinct attention. Residents and fellows are at increased risk for victimization given their unique positioning between learner and employee and significant workloads. The NASEM report advises institutions to proactively address sexual harassment, including patient-perpetrated events, through easily accessible guidance and response training.2 Yet our survey and analysis suggest an absence of such policy within the “Top 20 Hospitals”.

Limitations of our analysis include small sample size and descriptive data. Our findings may not be generalizable to all hospitals and GME programs. We did not account for sexual harassment training mandated under individual state laws, nor any reporting mechanisms detailed outside of online policies. Further investigation that broadens the analysis to all GME programs and identifies key policies and cultural environments associated with decreased incidence of sexual harassment is needed.

Patient-perpetrated sexual harassment can result in destabilization, isolation, and emotional turmoil for residents and fellows.5 While institutions cannot prevent inappropriate patient behavior, they can set expectations that contribute to institutional culture. Hospitals can send a clear message to all stakeholders: we will not tolerate abuse in any form. Empowering residents, fellows, and their supervisors to recognize and respond to patient-perpetrated sexual harassment through policy and training may mitigate future harms, increase physician retention, and improve wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Theodore J. Iwashyna for his continued support.

Funding/Support

This work was financially supported by NIH grants T32 HL7749-25 (EMV), T32 DK007378-38 (ALO), and T32-HL007853 (TMC).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

Results were shared as a poster presentation at the American Thoracic Society International Conference meeting in May 2019 in Dallas, TX.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, Lillie E, Perrier L, Tashkhandi M, Straus SE, Mamdani M, Al-Omran M, Tricco AC. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2014;89:817–27. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The U.S. News and World Report. US. U.S news announces 2017–18 best hospitals. Available at: https://www.usnews.com/info/blogs/press-room/articles/2017-08-08/us-news-announces-2017-18-best-hospitals. Accessed June 25, 2019.

- 4.Viglianti EM, Oliverio AL, Meeks LM. Sexual harassment and abuse: when the patient is the perpetrator. Lancet. 2018;392:368–70. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dzau VJ, Johnson PA. Ending Sexual Harassment in Academic Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1589–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1809846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]