INTRODUCTION

Increasing access to buprenorphine treatment for opioid use disorder is a key strategy for reducing overdoses.1 However, treatment capacity is limited because buprenorphine can only be prescribed by certified providers. To expand capacity, recent federal initiatives have increased the physician patient cap (which previously rose from 30 to 100 patients) to 275 patients, and have allowed nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) to obtain waivers.2 Previous research has shown that expanding buprenorphine prescribers for Medicaid populations leads to more buprenorphine prescriptions3; however, it is unclear if this relationship holds across all payer groups.

METHODS

Our main outcome was the total amount of buprenorphine dispensed per capita in each 3-digit zip code, the area representing all standard 5-digit zip codes that share the first three digits, containing on average 349,511 individuals in 2010. The total buprenorphine dispensed in each 3-digit zip and year was calculated using the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA)’s Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS), which tracks US dispensing of all opiate-related controlled substances. Our independent variable, also obtained from the DEA, was the count of providers certified to prescribe buprenorphine in 2015 and 2017 (the 2 years available to our team) in each 3-digit zip code. We also examined the influence of federally determined prescribing caps per physician of 30, 100, or 275 patients, and whether associations differed by provider type (physicians, PAs, or NPs).

We analyzed, for 2015 and 2017 separately, the association between a 3-digit zip codes’ number of certified providers per capita and the total buprenorphine prescribed in that area. We also conducted multivariate regression models combining 2 years of data to study the relationship between changes in dispensed buprenorphine and the number of certified physicians, controlling for area characteristics and for other factors that vary on an annual basis. More formally, our model includes indicators (fixed effects) for each year and each 3-digit zip code, which reduce potential confounding from unmeasured regional heterogeneity (e.g., area-level socioeconomic or healthcare market differences). The study was exempted by Indiana University’s Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

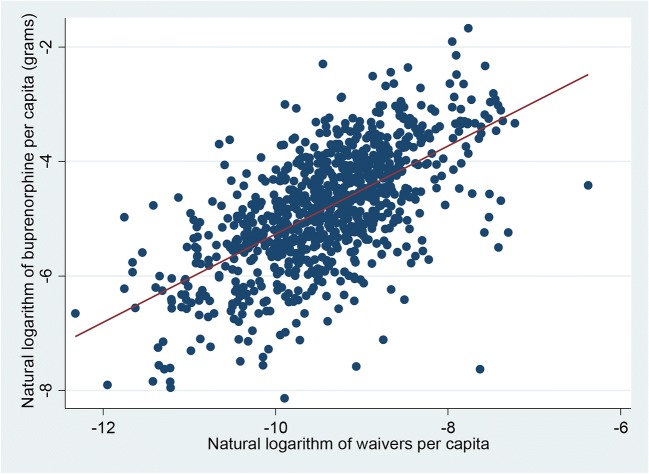

Using 2017 data, Figure 1 shows a positive relationship at the 3-digit zip code level between certified providers and total buprenorphine prescribed (R2 = 0.39). A similar relationship was present in 2015 (data not shown). Table 1 presents regression analyses examining the relationship between the number of providers and prescribed amounts of buprenorphine from 2015 to 2017. We find that one more certified provider per capita (column 1) was associated with a 9.07 g increase (95% CI, 3.53–14.60) in buprenorphine prescribed per capita. Column 2 shows results for different provider categories. Row 2 shows that with a patient limit of 100, rather than 30, adding one physician was associated with a 21.95 g increase (95% CI, 5.84–38.05); with a patient limit of 275, the increase was 111.10 g (95% CI, 90.51–131.70). We found no statistically significant relationship between numbers of certified NPs or PAs and changes in prescribing volume.

Figure 1.

The correlation between buprenorphine prescribed per capita and the number of certified providers per capita at the 3-digit zip code, 2017. Buprenorphine in grams for each 3-digit zip code area recorded from Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS). Numbers of certified providers were aggregated to the 3-digit zip code level from Drug Enforcement Agency’s provider list. Because much data were condensed at a very low value and high values are dispersed, making the relationship between variables difficult to discern, both variables were transformed using the natural logarithm. Only 2017 data are shown in this figure for space limitations; however, the relationship is also positive in 2015. A univariate regression line is also presented (goodness-of-fit R2 = 0.39).

Table 1.

Regression Table for Buprenorphine Prescribed Per Capita in 3-Digit Zip Code Areas, 2015 and 2017

| (1) | (2) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P | Coefficient (95% CI) | P | |

| Certified providers per cap (any limit) | 9.07 (3.53 to 14.60) | 0.001 | − 0.6 (− 6.53 to 5.33) | 0.843 |

| Certified MDs per cap (100 patients) | 21.95 (5.84 to 38.05) | 0.008 | ||

| Certified MDs per cap (275 patients) | 111.10 (90.51 to 131.70) | < 0.001 | ||

| Certified NPs/PAs per cap (30 patients) | 114.75 (− 43.29 to 272.78) | 0.154 | ||

| Number of Obs | 1,768 | 1,768 | ||

Each column of results is obtained from a separate regression in which the dependent variable is always the buprenorphine prescribed in the area in the year, and the key regressor is as noted in the row (different ways of measuring the number of certified providers). Buprenorphine in grams for each 3-digit zip code area is from Automation of Reports and Consolidated Orders System (ARCOS). Numbers of certified providers were aggregated to 3-digit zip code level from Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) provider lists. We also controlled for state-by-year fixed effects and 3-digit zip code fixed effects. A constant was also included in regressions

MD medical doctor, NP nurse practitioner, PA physician assistant

DISCUSSION

Higher numbers of certified buprenorphine providers were associated with substantial increases in total buprenorphine prescribed. This is an important finding even though many certified providers do not prescribe the maximum allowed.4 Given that a typical patient receives 14 mg per day for 180 days,5, 6 our findings suggest that adding one more certified provider increases access for 3.6 patients. The effects vary by the provider’s certification category: an additional provider with a 100-patient limit increases access for 8.71 patients; and an additional provider with a 275-patient limit increases access for 44.09 patients. Our findings suggest that, in the near term, increasing the number of 275 patient providers may be more effective at expanding buprenorphine treatment than increasing the number of providers with 30 patient certifications.

This study has limitations. As we use observational data, there are likely other factors that may confound the relationship between prescribers and amount dispensed. ARCOS data cannot differentiate between different drug formulations and as a result our measure of buprenorphine includes the small amount of buprenorphine prescribed for pain management (rather than addiction treatment). This likely biases our findings toward finding no relationship since no certification is required for pain management. Our study may also underestimate the relationship if buprenorphine received in one area is prescribed by a clinician in a neighboring community.5

Funding

Brendan Saloner received a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5K01DA042139-02).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Prior Presentations

None.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Christie C, Baker C, Cooper R, Kennedy CPJ, Madras B, Bondi FAGP. The president’s commission on combating drug addiction and the opioid crisis. Washington, DC, US Gov Print Off Nov. 2017;1.

- 2.Johnson K, Jones C, Compton W, Baldwin G, Fan J, Mermin J, et al. Federal response to the opioid crisis. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15(4):293–301. doi: 10.1007/s11904-018-0398-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wen H, Hockenberry JM, Pollack HA. Association of Buprenorphine-Waivered Physician Supply With Buprenorphine Treatment Use and Prescription Opioid Use in Medicaid Enrollees. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182943. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones CM, McCance-Katz EF. Characteristics and Prescribing Practices of Clinicians Recently Waivered to Prescribe Buprenorphine for the Treatment of Opioid Use Disorder. Addiction. 2018; [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Saloner B, Daubresse M, Caleb Alexander G. Patterns of buprenorphine-naloxone treatment for opioid use disorder in a multistate population. Med Care. 2017;55(7):669–76. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saloner B, Levin J, Chang H-Y, Jones C, Alexander GC. Changes in buprenorphine-naloxone and opioid pain reliever prescriptions after the Affordable Care Act Medicaid expansion. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181588. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]