Abstract

Aims

To estimate the incidence of direct oral anticoagulant drug (DOAC) use in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and to describe user and treatment characteristics in 8 European healthcare databases representing 6 European countries.

Methods

Longitudinal drug utilization study from January 2008 to December 2015. A common protocol approach was applied. Annual period incidences and direct standardisation by age and sex were performed. Dose adjustment related to change in age and by renal function as well as concomitant use of potentially interacting drugs were assessed.

Results

A total of 186 405 new DOAC users (age ≥18 years) were identified. Standardized incidences varied from 1.93–2.60 and 0.11–8.71 users/10 000 (2011–2015) for dabigatran and rivaroxaban, respectively, and from 0.01–8.12 users/10 000 (2012–2015) for apixaban. In 2015, the DOAC incidence ranged from 9 to 28/10 000 inhabitants in SIDIAP (Spain) and DNR (Denmark) respectively. There were differences in population coverage among the databases. Only 1 database includes the total reference population (DNR) while others are considered a population representative sample (CPRD, BIFAP, SIDIAP, EGB, Mondriaan). They also varied in the type of drug data source (administrative, clinical). Dose adjustment ranged from 4.6% in BIFAP (Spain) to 15.6% in EGB (France). Concomitant use of interacting drugs varied between 16.4% (SIDIAP) and 70.5% (EGB). Cardiovascular comorbidities ranged from 25.4% in Mondriaan (The Netherlands) to 82.9% in AOK Nordwest (Germany).

Conclusion

Overall, apixaban and rivaroxaban increased its use during the study period while dabigatran decreased. There was variability in patient characteristics such as comorbidities, potentially interacting drugs and dose adjustment. (EMA/2015/27/PH).

Keywords: anticoagulants, arrhythmia, cardiovascular, drug utilization, pharmacoepidemiology

What is already known about this subject

An increase in the number of direct oral anticoagulant drug (DOAC) users with a diagnosis of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) has been reported since their marketing in several national/regional studies in Europe, but no cross‐national comparison is available.

The characteristics of DOAC users related to NVAF have been described but concomitant use of potentially interacting drugs is rarely reported. DOAC users are usually younger than 75 years, male and 20% of DOAC users with NVAF receive dose adjustment related to renal function.

What this study adds

Overall DOAC incidences varied from 1.93 to 2.60 and 0.11 to 8.71 users/10 000 (2011–2015) for dabigatran and rivaroxaban, respectively, and from 0.01 to 8.12 users/10 000 (2012–2015) for apixaban.

In 2015, the new user DOAC incidence ranged from 9 to 28/10 000 inhabitants 18 years and older in SIDIAP (Catalonia, Spain) and DNR (Denmark) databases respectively, this being higher in men than in women and in those older than 75 years.

Concomitant use of contraindicated or potentially interacting drugs varied between 16.4% (SIDIAP) and 70.5% (EGB). Dose adjustment related to age or renal function varied from 4.6% (BIFAP, Spain) to 15.6% (EGB, France).

1. INTRODUCTION

Patients with atrial fibrillation have long been treated with vitamin K antagonists for the prevention of cerebral embolism. The newer direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) have been approved by the European Union since 2008. The first was dabigatran (2008), a http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=2362 inhibitor; this was followed by rivaroxaban (2008), apixaban (2011) and edoxaban (2015), http://www.guidetopharmacology.org/GRAC/ObjectDisplayForward?objectId=2359 inhibitors. The first approval for the prevention of stroke and systemic embolism in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) was for dabigatran in 2011 (Table S1). DOACs are currently recommended by the European Society of Cardiology as first‐line anticoagulant treatment in NVAF, without mitral stenosis or mechanical heart valves.1

The incidence of NVAF is estimated to be 3% in adults aged 20 or older, increasing with age,2, 3 with incidence of 12% in females and 14% in males aged over 75 years.3 Atrial fibrillation is associated with increased cardiovascular morbidity, such as heart failure and stroke.4, 5 Clinical trials have shown that both vitamin K antagonists and DOACs reduce stroke and mortality in AF patients.5, 6 Utilization of DOACs for stroke prevention in NVAF and their effectiveness and safety in clinical practice have been assessed in several European countries.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 However, little is known about their use beyond clinical trial conditions, especially in patients with hepatic or renal impairment. Findings from 2 studies from USA and Australia showed that inappropriate dosing occurred among patients with renal failure, and there is still uncertainty about appropriate dosing in these patients.14, 15 In addition, the very elderly, who may be at increased risk of adverse effects with inappropriate DOAC use, are poorly represented in clinical trials.16, 17

This cross‐national comparison drug utilization study, using longitudinal data from 8 electronic health care databases in 6 European countries, uses a common protocol to characterize DOAC users in a real‐world setting in order to establish the effectiveness of existing risk minimization measures and their appropriateness for the future. Its objectives are to assess incidence of use and user characteristics, including concomitant exposure to potentially interacting medicines and rates of dose adjustment related to age or renal impairment.

2. METHODS

2.1. Data sources

We conducted a longitudinal drug utilization study in 6 countries between January 2008 and December 2015. Data were retrieved from the following 8 databases: (i) the Dutch Mondriaan project, which includes the Julius General Practitioner Network (JHN) database18; (ii) the Danish National Registries (DNR), which includes the Danish National Patient Register, Danish National Prescription Registry and Danish Civil Registration System19, 20, 21; (iii) the AOK Nordwest database22, 23, Germany; (iv) the Bavarian Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians database, referred to here as Bavarian CD, Germany24; (v) the Base de datos para la Investigación Farmacoepidemiológica en Atención Primaria (BIFAP), Spain25; (vi) the Information System for the Development of Research in Primary Care (SIDIAP), Catalonia, Spain26; (vii) the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD), UK27, 28; (viii) The Echantillon Généraliste de Bénéficiaires (EGB), France.29 The databases characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Database characteristics

| Mondriaan | Danish National Registries | AOK Nordwest | Bavarian Claims | BIFAP | SIDIAP | CPRD | EGB | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source population (million inhabitants) | 0.4 | 5.5 | 2.7 | 10.5 | 7.5 | 5.8 | 12.5 | 0.7 | |

| Population coverage | 3% | 100% | 24% | 84% | 16.4%a | 80% | 8%a | Representative sample of Système National d'Informations Inter‐Régimes de l'Assurance Maladie [98.8%] | |

| Year(s) covered for this study | 2012–2015b | 2008–2015 | 2008–2015 | 2008–2015 | 2008–2015 | 2009–2015 | 2008–2015 | 2013–2015c | |

| Type of databased | GP prescribing data and pharmacy dispensing data. | Dispensing data from community pharmacies. | Claims database including data for dispensed reimbursed drugs | Claims database including data for dispensed reimbursed drugs. | General practice prescribing data/reimbursed data. | General practice prescribing data/reimbursed data. | General practice prescribing data. | Claims database including dispensed reimbursed data. | |

| Data available since | 1991 | 1994 | 2007 | 2008 | 2001 | 2006 | 1987 | 2004 | |

| Demographic variables available | |||||||||

| Date of registration | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (first consultation) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Date of transferring out | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes (last consultation) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Date of birth | DD‐MM‐YY | MM‐YY | MM‐YY | MM‐YY | MM‐YY | MM‐YY | MM‐YY | YY | |

| Sex | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Drug information available | |||||||||

| Active international coding | ATC | ATC | ATC | ATC | ATC | ATC | BNF | ATC | |

| Product coding | HPK | Nordic article number | PZN | PZN | CNF | Yese | Product code | CIP‐13 | |

| Date of prescribing/dispensing | Yes | Yes | Primary care sector: Yes | Yes (for each prescription the quarter is documented) | Yes | Yesf | Yes | Yes | |

| Primary care sector | |||||||||

| GP | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Specialist | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | |

| Secondary care sector | No | No | Yes—only for a few selected (expensive) compounds, but no (D)OAC prescriptions | No | No | No | No | Yes—only for a few selected (expensive) compounds, but no (D)OAC prescriptions | |

| Quantity prescribed/dispensed | Yes | Yes | Yes (package size) | Yes (package size) | Yes | Yesg | Yes | Yes | |

| Dosing regimen | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yesh | Yes | No | |

| Outcome information | |||||||||

| Outpatient primary care diagnosis | ICPC | No | ICD‐10‐GM (quarterly base) | ICD‐10‐GM (for each diagnosis the quarter is documented) | ICPC‐2, ICD‐9 | ICD‐10 | ICD‐9, ICD‐10 | ICD‐10 | |

| Hospital discharge diagnosis | No | ICD‐8, ICD‐10 | ICD‐10‐GM | No | No | Noi | ICD‐9, ICD‐10 | ICD‐10 | |

| Laboratory tests | Yes | No | No | No | Yes (as requested by GP) | Yes | Yes | No | |

| Mortality | Yes | Yes | No (incompletely recorded, e.g. no follow‐up for patients leaving the AOK) | No | Yes (no cause of death) | Yes (no cause of death) | Yes | Yes (no cause of death) | |

Representative of general population.

No data on DOAC) use available until 2012. DOACs were not prescribed by general practitioners in the Netherlands before 2012.

No data on DOAC use available until 2013.

Prescribing databases: collect information on prescribed drugs by GP; Reimbursement databases: collect information on dispensed drugs funded by Health Care Services; Dispensing databases: collect all dispensation of prescription drugs regardless of the drug's reimbursement status (Ref. Eriksson E and Ibañez L. Secondary data sources for drug utilization research. In Elseviers M et al. Drug utilization research. Methods and applications. John Willey and Sons, 2016).

Registered but not available for research due to confidentiality reasons;

For dispensing: MM/YY;

Number of reimbursed packages;

Only in prescribing data;

Available for 28% of included population.

(D)OAC, (direct) oral anticoagulant; GP, general practitioner; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Classification; BNF, British National Formulary; HPK, Handels Product Code; PZN, Pharma Zentral Nummer; CNF, Código Nacional Farmacéutico; ICD (International Classification of Diseases; ICD‐10‐GM: ICD ‐10‐German Modification), ICPC (International Classification of Primary Care).

2.2. Study population

The study population was defined as all new users (age ≥18 years) of the DOACs of interest (dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban). Only those patients with a diagnosis of NVAF (see codes in supplementary material, Table S2) were included. A common protocol was applied for data extraction and analysis (EU PASS Register No: 16014) for each database.30 Results were blinded to each database lead until the analysis was completed.

New users were defined as patients initiating DOAC during the study period without any use of DOAC for at least 365 days prior to the index date (date of first DOAC prescription). Flow charts for patient inclusion for each database are shown in Figure S1.

Patients registered in the database <1 year (365 days) before the index date and patients with a history of valvular atrial fibrillation on index date or any time prior to initiating DOACs were excluded. Follow‐up of each patient was until therapy switch, discontinuation or end of study, whichever came first. Switchers were defined as patients with a subsequent prescription of another type of (D)OAC, within the first treatment episode. Discontinuers were defined as patients who did not receive subsequent DOACs within 30 days following the theoretical end date of the prior DOAC.

As DOACs can be prescribed for indications other than NVAF, a sensitivity analysis was performed excluding patients with multiple potential DOAC indications in a ± 3 month period around the first DOAC prescription.

2.3. Ethical approval

Participants in each country had study approval from the corresponding data owners. No other requirement was required since anonymized data were used. Additionally, the study protocol was revised and approved by an internal European Medicines Agency expert panel.

2.4. Outcomes

The main outcome was assessing incidence of DOAC use in patients with NVAF during the study period.

Annual period incidences are estimated and defined as the number of new users during the year of interest, divided by the total number of patients in the database at midyear (1 July).

Secondary aims were to assess concomitant use of interacting drugs, defined as any prescription of a potentially interacting medicinal product as indicated in the Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) during the first DOAC treatment episode of each patient. A list of the concomitant interacting drugs considered in the SmPC is given in eSupplementary Material (Table S3). A treatment episode was defined as series of prescriptions for a DOAC, independent of dose changes, considering a gap of up to 30 days, constructed according to the method of Gardarsdottir et al.31

Furthermore, the occurrence of dose adjustment, defined as changing from 1 tablet strength to another strength of the same active substance, was assessed during the first treatment episode.

2.5. Analysis

The analysis is descriptive and stratified by database, individual DOAC, age group (<75, 75–79, ≥80 years), sex and calendar year.

The baseline characteristics (demographics [sex, age]), comorbidities, chronic kidney disease (CKD), renal function, laboratory data when available, hepatic impairment, previous major haemorrhagic episodes, previous cardiovascular events (see codes in Table S4) and concomitant exposure to potentially interacting medicines of DOAC users are presented as absolute number and percentages for each variable.

For all databases, annual period incidences, with direct standardisation by age and sex was performed based on the European standard population corresponding to each year analysed.32 An incidence percentage change in DOAC users with NVAF is given in comparison to the first calendar year when NVAF became an approved indication for use (2012 for dabigatran and rivaroxaban, 2013 for apixaban). However, in the EGB database, DOAC percentage change was assessed for 2013–2014 since these are the calendar years with complete information. In addition, a percentage change of the standardized incidence, weighted by the database populations, was calculated from the first to the last calendar year of use.

Percentage of new DOAC users exposed to potentially interacting medication is expressed as the absolute number and percentage of the total DOAC users. Dose adjustment is expressed as the percentage of patients with adjusted dosage following the requirements of the SmPC and presented either related to change in age or renal function, as indicated in the SmPC.

2.6. Nomenclature of targets and ligands

Key protein targets and ligands in this article are hyperlinked to corresponding entries in http://www.guidetopharmacology.org, the common portal for data from the IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY,33 and are permanently archived in the Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18.34

3. RESULTS

3.1. New users

A total of 186 405 new DOAC users (age ≥18 years) with NVAF were identified during the study period.

Of all new DOAC users, 91 804 (49%), 52 495 (28%) and 42 106 (22%) received rivaroxaban, dabigatran and apixaban, respectively.

3.2. Baseline characteristics

Most of the users were age 75 years or older (48.8% in Mondriaan to 60.8% in BIFAP). The mean age ranged from 69.3; SD 11.3 (Mondriaan) to 75.7; SD 10.4 years (BIFAP) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics for all direct oral anticoagulant new users

| Mondriaan | Danish National Registries | AOK Nordwest | Bavarian Claims | BIFAP | SIDIAP | CPRD | EGB | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 460 | 44 876 | 21 718 | 84 276 | 14 161 | 11 962 | 6931 | 2021 | |||||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| Female | 189 | 41.1 | 20 331 | 45.3 | 11 650 | 53.6 | 44 070 | 52.3 | 6755 | 47.7 | 5598 | 46.8 | 3049 | 44.0 | 867 | 42.9 |

| Male | 271 | 58.9 | 24 545 | 54.7 | 10 068 | 46.4 | 40 206 | 47.7 | 7406 | 52.3 | 6364 | 53.2 | 3882 | 56.0 | 1154 | 57.1 |

| Age (y), mean (SD) | 69.3 | 11.3 | 73.9 | 10.9 | 74.5 | 11.0 | 74.5 | 11.0 | 75.7 | 10.4 | 74.6 | 10.9 | 74.7 | 11.0 | 72.8 | 12.0 |

| 18–74 | 310 | 67.4 | 22 977 | 51.2 | 8795 | 40.5 | 36 658 | 43.5 | 5558 | 39.2 | 5165 | 43.2 | 3110 | 44.9 | 995 | 49.2 |

| 75–79 | 61 | 13.3 | 7258 | 16.2 | 4785 | 22.0 | 17 979 | 21.3 | 2647 | 18.7 | 2249 | 18,8 | 1300 | 18.7 | 353 | 17.5 |

| ≥80 | 89 | 19.3 | 14 641 | 32.6 | 8138 | 37.5 | 29 639 | 35.2 | 5956 | 42.1 | 4548 | 38,0 | 2521 | 36.4 | 673 | 33.3 |

| Comorbidities | 143 | 31.1 | 29 161 | 66.7 | 18 952 | 87.3 | 73 488 | 87.2 | 6865 | 48.5 | 6437 | 53.8 | 4337 | 62.6 | 1042 | 51.6 |

| Hepatic impairment | 0 | 0 | 969 | 2.1 | 3119 | 14.4 | 14 845 | 17.6 | 33 | 0.2 | 27 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.0 | 52 | 2.6 |

| Chronic kidney disease (by diagnosis codes) | 0 | 0 | 2055 | 4.6 | 4377 | 20.1 | 20 287 | 24.1 | 226 | 1.6 | 509 | 4.3 | 309 | 4.5 | 58 | 2.9 |

| Previous major haemorrhagic episodes | 28 | 6.1 | 1642 | 3.6 | 2634 | 12.1 | 13 745 | 16.3 | 532 | 3.8 | 500 | 4.2 | 177 | 2.6 | 60 | 3.0 |

| Haemorrhagic stroke/intracranial bleeding | 21 | 4.6 | 231 | 0.5 | 382 | 1.7 | 2087 | 2.5 | 37 | 0.3 | 66 | 0.5 | 15 | 0.2 | 14 | 0.7 |

| Extracranial or unclassified major bleeding | 0 | 0 | 833 | 1.8 | 1824 | 8.4 | 8182 | 9.7 | 326 | 2.3 | 300 | 2.5 | 114 | 1.6 | 34 | 1.7 |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 7 | 1.5 | 536 | 1.2 | 903 | 4.1 | 4036 | 4.8 | 168 | 1.2 | 116 | 1.0 | 49 | 0.7 | 14 | 0.7 |

| Traumatic intracranial bleeding | 0 | 0 | 136 | 0.3 | 40 | 0.2 | 671 | 0.8 | 10 | 0.1 | 30 | 0.2 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0.2 |

| Previous cardiovascular events | 117 | 25.4 | 29 959 | 65.0 | 17 998 | 82.9 | 64 618 | 76.7 | 5330 | 37.6 | 5653 | 47.3 | 3107 | 44.8 | 996 | 49.3 |

| Coronary heart disease: Angina/myocardial infarction | 68 | 14.8 | 10 584 | 23.6 | 12 439 | 57.3 | 46 062 | 54.6 | 1932 | 13.6 | 2156 | 18.0 | 1286 | 18.6 | 376 | 18.6 |

| Congestive heart failure | 41 | 8.9 | 20 134 | 44.9 | 9708 | 44.7 | 39 363 | 46.7 | 1921 | 13.6 | 2278 | 19.0 | 755 | 10.9 | 690 | 34.1 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 0 | 0 | 1768 | 3.9 | 4876 | 22.4 | 16 782 | 19.1 | 531 | 3.7 | 784 | 6.5 | 308 | 4.4 | 0 | 0 |

| Stroke/transient ischaemic attack | 26 | 5.7 | 9555 | 21.3 | 6098 | 28.1 | 22 789 | 27.0 | 2099 | 14.8 | 2418 | 20.2 | 1474 | 21.3 | 208 | 10.3 |

| Deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism | 0 | 0 | 2121 | 4.7 | 1114 | 5.1 | 5247 | 6.2 | 58 | 0.4 | 68 | 0.6 | 236 | 3.4 | 21 | 1.0 |

| Aortic plaque | 4 | 0.9 | 140 | 0.3 | 961 | 4.4 | 4163 | 4.9 | 952 | 6.7 | 9 | 0.1 | 11 | 0.2 | 121 | 6.0 |

Users were most frequently male (range 52.3–58.9%), except in the AOK and Bavarian CD databases where the opposite was found (range 46.4–47.7%).

The proportion of patients with comorbidities ranged from 31.1% (Mondriaan) to 87.3% (AOK). Most frequent were previous cardiovascular events (25.4% in Mondriaan to 82.9 and 76.7% in AOK and Bavarian CD, respectively).

The number of patients with acute or chronic kidney disease, identified through diagnosis codes, ranged from 0% in the Mondriaan to 24.1% in the Bavarian CD databases. Assessment of laboratory values with moderately reduced kidney function (Mondriaan, BIFAP, SIDIAP and CPRD) showed a range from 3.0% (Mondriaan) to 22.6% (CPRD). DOAC users with severely or very severely reduced renal function were very uncommon in these databases. However, the proportion of unregistered information was usually high (range: 3.4% in CPRD to 77.9% in BIFAP; Table S5).

3.3. Incidence

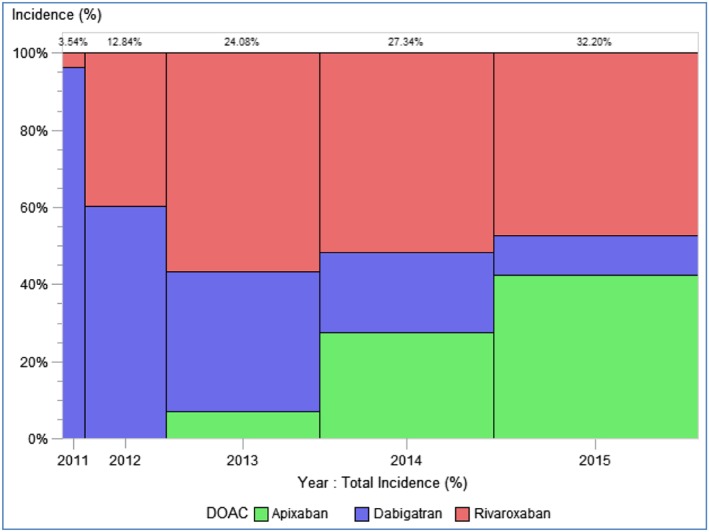

During this period, overall DOAC incidence increased (Figure 1). Standardized incidences varied from 1.93–2.60 and 0.11–8.71 users/10 000 (2011–2015) for dabigatran and rivaroxaban, respectively, and from 0.01–8.12 users/10 000 (2012–2015) for apixaban (Table 3). Apixaban displayed the highest standardized incidence percentage change from the first year of use following approval in NVAF to the final year studied (543.2%), followed by rivaroxaban (100.2%; Figure 1). This was mainly driven by a sharp increase in EGB. The standardized percentage incidence change for this first calendar year compared to the previous year was maximum in EGB (10 550.0%) and minimum in Bavarian CD (218.6%); values comparing for 2014 and 2015 were maximum in Mondriaan (868.5%) and minimum in SIDIAP (35.1%).The percentage for rivaroxaban increased in all databases during the first calendar year of use, except in EGB, with the greatest increase in CPRD (120.9%); a decrease was seen in the 2 German databases and EGB in 2014–2015 (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Distribution of the total standardized incidence by individual direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC; 2011–2015)

Table 3.

Standardized incidences by individual direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) per year (new users per 10 000 people)

| DOAC | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran | 0.10 | 2.60 | 5.33 | 4.98 | 3.49 | 1.93 |

| Rivaroxaban | 0.06 | 0.11 | 4.35 | 8.77 | 8.85 | 8.71 |

| Apixaban | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 1.26 | 4.99 | 8.12 |

Table 4.

Standardized incidence percentage change in direct oral anticoagulant new users with a diagnosis of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) in the time periods for the first and last calendar year of use after NVAF indication approval (2012–2015)

| Incidence percentage change for the first calendar year of use after NVAF approvala | Incidence percentage change 2014–2015 | Incidence percentage change from the first calendar year of use to 2015 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dabigatran (%) | Apixaban (%) | Rivaroxaban (%) | Dabigatran (%) | Apixaban (%) | Rivaroxaban (%) | Dabigatran (%) | Apixaban (%) | Rivaroxaban (%) | |

| Mondriaan | −22.93 | 833.97 | 2397.26 | 32.54 | 868.50 | 63.36 | 11.52 | 8945.51 | 21 048.75 |

| NRD | −4.58 | 268.27 | 266.94 | −63.54 | 60.94 | 42.41 | −73.56 | 492.68 | 418.75 |

| AOK Nordwest | −8.04 | 313.13 | 98.40 | −35.54 | 80.03 | −12.89 | −66.09 | 643.75 | 74.60 |

| Bavarian Claims | −18.43 | 218.61 | 67.96 | ‐ 41.56 | 47.54 | −24.18 | −74.38 | 370.09 | 14.99 |

| BIFAP | −15.02 | 712.82 | 227.42 | −6.08 | 52.37 | 12.50 | −32.81 | 1138.46 | 320.97 |

| SIDIAP | −7.13 | 462.60 | 247.88 | −5.80 | 35.13 | 27.75 | −26.43 | 660.23 | 480.62 |

| CPRD | 80.98 | 774.46 | 732.89 | 3.55 | 180.91 | 120.90 | 88.31 | 2356.46 | 4902.39 |

| EGB | −69.55 | 10 550.0 | −32.33 | −56.37 | 162.44 | −16.21 | −86.72 | 27850.0 | −43.30 |

Data for dabigatran and rivaroxaban are calculated for 2012–2013. Data for apixaban are calculated for 2013–2014 in all databases. Data for each DOAC are calculated for 2013–2014 in EGB.

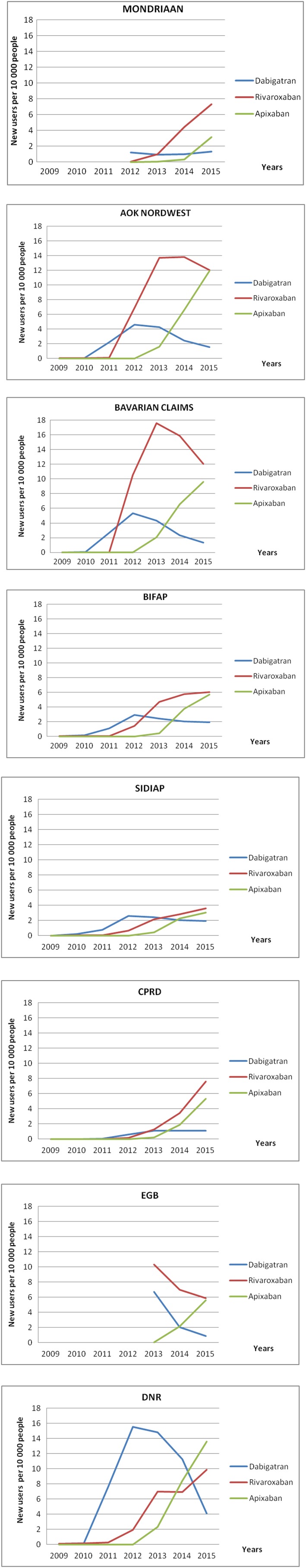

The standardized figures show that the incidence of dabigatran clearly increased in most databases from 2010 to 2012, with the highest value in the DNR (15.5 new users per 10 000). The CPRD and Mondriaan figures increased slightly at the end of the study period. The apixaban standardized incidence increased across 2013–2015 in all databases. The maximum value was observed in the DNR database in 2015 (13.6 new users per 10 000). The rivaroxaban standardized incidence increased over time in all databases since its arrival on the market, except in EGB; however, it started to decrease in Bavarian CD in 2014 and AOK in 2015. The Bavarian CD database presented the highest rivaroxaban standardized incidence in 2013 (17.5 new users per 10 000). Rivaroxaban showed the highest annual incidence values in the 2012–2015 period in all databases except in the DNR (Figure 2; Tables S6–S9). The DOAC incidence increased in males and females across the study period in most databases, especially in those over 75 years, whose incidences were higher than those, men and women, younger than 75 years (Figures S2–S4).

Figure 2.

Standardized incidences by individual direct oral anticoagulant in each database

In 2015, the incidence of DOAC use ranged from 8.6 per 10 000 in SIDIAP to 27.6 per 10 000 in DNR (Table S6), with a higher incidence in men than in women.

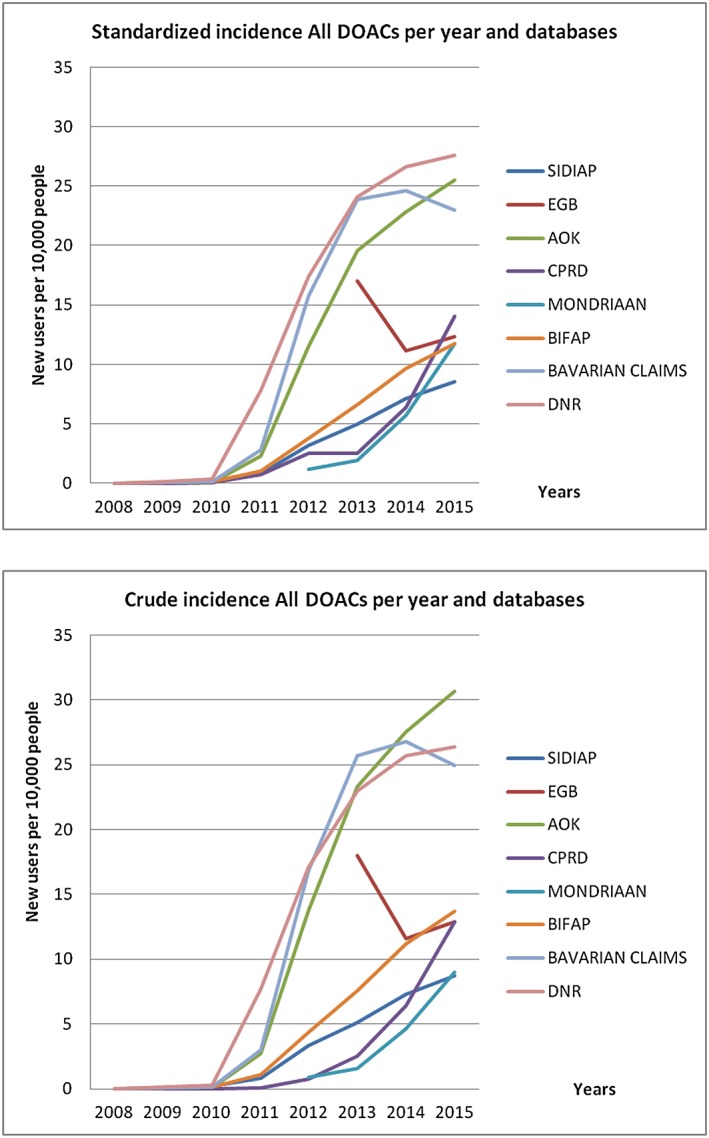

Figure 3 shows the incidence data for all DOACs, per database and per year, for the whole study period.

Figure 3.

Standardized and crude incidence for all direct oral anticoagulants per year and database

3.4. Concomitant use of potentially interacting drugs

The proportion of patients who received an interacting drug during the first treatment episode ranged from 16.4% (SIDIAP) to 70.5% (EGB). Concomitant use of contraindicated anticoagulants varied between 0.4% (CPRD) and 24.3% (EGB). Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) varied from 4.3% (Mondriaan) to 26.0% (Bavarian CD) and antiplatelet drugs from 1% (SIDIAP) to 18.1% (EGB). The most frequent interacting drugs were heparins in AOK, BIFAP and Bavarian CD (8.4, 10.4 and 12.1%, respectively), amiodarone in SIDIAP, DNR and EGB databases (5.7, 6.2 and 42.2%, respectively) and verapamil in Mondriaan (4.1%; Table 5).

Table 5.

Concomitant treatment during the first treatment episode

| Mondriaan | Danish National Registries | AOK Nordwest | Bavarian Claims | BIFAP | SIDIAP | CPRD | EGB | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 460 | 95 937 | 21718 | 84 459 | 14 161 | 11 962 | 6931 | 2021 | |||||||||

| n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | n | (%) | |

| CONCOMITANT MEDICATION (potential interacting medicine products) | 94 | 20.4 | 15 765 | 37.8 | 10 585 | 48.7 | 44 394 | 52.7 | 6781 | 47.9 | 1963 | 16.4 | 1785 | 25.8 | 1425 | 70.5 |

| Concomitant treatment with any other anticoagulants (contraindicated) | 21 | 4.6 | 446 | 1.1 | 3730 | 17.2 | 17 153 | 20.4 | 1425 | 10.1 | 355 | 3.0 | 29 | 0.4 | 492 | 24.3 |

| Most frequent drug | Vitamin K antagonists | 3.9 | Vit K antagonists | 0.6 | Heparin group | 8.4 | Heparin group | 12.0 | Heparin group | 10.4 | Heparin group | 2.9 | Vitamin K antagonists | 0.4 | Heparin group | 12.2 |

| Platelet aggregation inhibitors excl. Heparin | 23 | 5.0 | 6455 | 14.4 | 2140 | 9.9 | 9298 | 11 | 1859 | 13.1 | 123 | 1.0 | 849 | 12.2 | 365 | 18.1 |

| Strong CYP3A4 and/or P‐gp inhibitor comedication | 0 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 329 | 1.5 | 1746 | 2.0 | 282 | 2.0 | 107 | 0.9 | 29 | 0.4 | 3 | 0.1 |

| Most frequent drug | NA | NA | Dronedarone | 0.3 | Dronedarone | 1.3 | Dronedarone | 1.9 | Dronedarone | 1.6 | Dronedarone | 0.8 | Dronedarone | 0.4 | Cyclosporine | 0.1 |

| Not strong CYP3A4 and/or P‐gp inhibitors | 30 | 6.5 | 5473 | 12.2 | 2203 | 10.1 | 8172 | 9.7 | 1592 | 11.2 | 712 | 5.9 | 623 | 9.0 | 900 | 44.5 |

| Most frequent drug | Verapamil | 4.1 | Amiodarone | 6.2 | Amiodarone | 6.7 | Amiodarone | 6.5 | Amiodarone | 8.8 | Amiodarone | 5.7 | Amiodarone | 6.4 | Amiodarone | 42.2 |

| CYP3A4 and/or P‐gp inducers | 1 | 0.2 | 194 | 0.4 | 189 | 0.9 | 556 | 0.7 | 80 | 0.5 | 26 | 0.2 | 36 | 0.5 | 5 | 0.2 |

| Most frequent drug | NA | NA | Carbamazepine | 0.3 | Carbamazepine | 0.7 | Carbamazepine | 0.5 | Carbamazepine | 0.2 | Rifampicin | 0.1 | Phenytoin | 0.3 | Rifampicin/ Carbamzepine | 0.1% |

| Transporter interaction: CYP3A4 and/or P‐gp | 8 | 1.7 | 456 | 1.0 | 123 | 0.6 | 160 | 0.2 | 139 | 0.1 | 58 | 0.5 | 10 | 0.1 | 21 | 1.0 |

| Most frequent drug | Naproxen | 1.3 | Fluconazole | 0.7 | Naproxen | 0.3 | Naproxen | 0.1 | Naproxen | 0.5 | Naproxen | 0.3 | Naproxen | 0.2 | Fluconazole | 0.6 |

| Nonsteroidal anti‐inflammatory drug | 20 | 4.3 | 5878 | 13.1 | 5319 | 24.5 | 21935 | 26.0 | 3337 | 23.6 | 696 | 5.8 | 313 | 4.5 | 308 | 15.2 |

| Other drugs (only for dabigatran) | 9 | 2.0 | 2704 | 6.0 | 361 | 1.7 | 1417 | 1.7 | 507 | 3.6 | 257 | 2.1 | 700 | 10.1 | 47 | 2.3 |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | 3 | 0.7 | 2380 | 5.3 | 304 | 1.4 | 1145 | 1.4 | 411 | 2.9 | 210 | 1.8 | 629 | 9.1 | 39 | 1.9 |

| Serotonin‐norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors | 6 | 1.3 | 406 | 0.9 | 63 | 0.3 | 346 | 0.4 | 126 | 0.9 | 64 | 0.5 | 83 | 1,2 | 10 | 0.5 |

P‐gp, P‐glycoprotein.

3.5. Dose adjustment

The information on dose adjustment was available in BIFAP, SIDIAP, CPRD and EGB, varying from 4.6% in BIFAP to 15.6% in EGB. The proportion of dose adjustments related to changes in renal function or age was <1% in the 3 databases where this information was available (BIFAP, SIDIAP and CPRD). In the Mondriaan database there were no dose changes recorded. DNR, AOK and Bavarian CD databases do not have this information registered (Table S5).

3.6. Sensitivity analysis

Results from the main analysis were compared with results from patients with only NVAF diagnosis. The total number of patients treated with DOACs decreased slightly, but the proportions of the individual DOAC were stable.

Regarding renal function at baseline and dose adjustment, the numbers were quite similar. The percentage of concomitant interacting medications increased in SIDIAP database both for all DOACs and individual DOACs. The percentage of previous cardiovascular events was lower for all DOACs across all databases and the overall percentage of previous haemorrhagic events was similar (Tables S10–S12).

4. DISCUSSION

Using a common protocol, we assessed the incidence of DOAC use during 2009–2015 and the characteristics of 186,405 users from 8 health care databases in 6 European countries (2008–2015). To our knowledge this is the first cross‐national drug utilization study providing the incidence of DOAC use in NVAF patients at a national/regional level, across several European countries. Only a few, single country European studies with similar inclusion criteria have been published, which only provide number of DOAC users rather than incidence figures.10, 12, 35, 36

During the study period, the overall incidence of DOAC user increased, except in the EGB database; the individual DOAC with the highest increase was apixaban followed by rivaroxaban. The largest incidence increase was for apixaban in the EGB. It was maximum for apixaban in the first calendar year of use in EGB (10 550.0) and minimum in Bavarian (218.6) while the values for 2014–2015 were maximum in Mondriaan (868.5) and minimum in SIDIAP (35.1). The striking increase for apixaban in EGB is due to the fact that its use was very low in 2013. In 2015, the incidence of DOAC use ranged from 8.7 per 10 000 in SIDIAP to 27.6 per 10 000 in DNR, with a higher incidence in men and in those older than 75 years.

The differences in incidence across the databases might be explained by the high proportion of previous cardiovascular events in AOK, Bavarian CD and DNR databases (82.9, 76.7 and 65.0%, respectively), which may result in higher incidence of NVAF in these populations. These results correlate well with the distribution of hospital discharges for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in these countries.37

Furthermore, differences in incidence could arise from the characteristics of the databases such as: prescription vs dispensing databases (DOACs prescribed are not necessarily dispensed), inclusion of prescriptions from specialists (although we do not expect differences in the management of NVAF between primary and specialist care since the European guidelines do not differentiate), population coverage (DNR is the only national database), different prescribing patterns in different countries, health services characteristics and their reimbursement policies, publication of guidelines (local or European), media and marketing policies.9, 38

Several national/regional studies have reported increases in the number of DOAC users, despite the NVAF population used differing from ours.9, 10, 39, 40 The incidence increased in both the males and females across the study period in most databases. More specifically, incidence was higher in males than in females, since NVAF is more common in men.10, 35, 41, 42

4.1. Incidence of individual DOACs

Overall, rivaroxaban presented the highest incidence figures, except in the DNR, followed by apixaban and dabigatran. The initial steep increase in rivaroxaban and apixaban incidence observed in most of the databases appeared by the end of 2011 and 2012 respectively, after approval for stroke prevention.43 This sharp increase was not observed for dabigatran as clearly in any of the databases. Other studies have shown a steep increase in users for each DOAC after their marketing.36, 39

4.2. Demographic characteristics

The mean age of our study population reflected other European studies on users of DOAC with NVAF, despite varying inclusion criteria.10, 12, 35, 36, 39, 41, 44 In line with other studies, we found that most of the users were older than 75 years, except in Mondriaan and DNR databases.10, 12, 40

A higher proportion of males was observed in all except the German databases, similarly to other published studies.10, 12, 35, 36, 41 The larger proportion of women in the German databases could be related to the characteristics of the population or to differences in NVAF incidence. Other studies have reported that female patients are more prevalent than males in those older than 75 or 80 years.45, 46

4.3. Baseline clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics observed are comparable to similar studies which used OAC naive or non‐naive NVAF patients.10, 35, 36 However, there is heterogeneity of the demographics and baseline characteristics across the databases. Different population coverage across the databases, as well as differences in the prevalence of cardiovascular diseases, could explain the observed differences.37

Previous cardiovascular events were the most frequent comorbidity across all databases. The observed high proportion of previous cardiovascular events in the German databases correlates with the high percentage of cardiovascular problems observed in Germany.37 It might also be related to the inclusion of data from medical specialists in the German databases, whereas many of the other databases in this study consider data from general practitioners only. In addition, resource allocation for German sickness funds is based on the so‐called morbidity‐oriented risk structure compensation scheme. Therefore, all primary and secondary diagnoses must be coded to enable appropriate calculations.47 The low prevalence in Mondriaan database might be because only the least critical patients received DOAC from primary care, as opposed to specialists.

The unexpectedly high proportion of CKD in the AOK and Bavarian CD populations may be explained by a higher proportion of patients with cardiovascular comorbidities or the inclusion of nonspecific codes.

4.4. Concomitant use of potentially interacting drugs

Concomitant use of drugs has been reported to be low and in very few studies.35 Concomitant treatment with other anticoagulant drugs was present in variable proportions, around 20% in the 2 German databases, and EGB. This is of concern since these patients might have a higher haemorrhagic risk. The presence of a high cardiovascular comorbidity proportion in the German databases could partly explain a higher use of medications. Furthermore, these 3 databases include reimbursed drugs from specialist prescriptions. However, some of this use could also be related to switching to anticoagulant therapy.

The concomitant use of cardiovascular drugs has been reported in some studies, in particular antiplatelet drugs, between 11 and 30% of users12, 36; similarly, antiplatelet drugs were used in 10–18% of the DOAC users in several databases in our study. Amiodarone, a strong P‐glycoprotein inhibitor, was the most frequent potentially interacting drug in several databases. Lower use has been described in the OAC naïve Danish study.36

NSAIDs have been reported in similar or somewhat lower proportions in other studies.12, 35, 41 Certain NSAIDs are available over the counter in some countries, as well as on prescription. This, together with differing prescriber behaviours treating pain or inflammatory conditions, may account for some of the observed differences.48

4.5. Dose adjustment related to age or changes in renal function

The proportion of dose adjustment related to age or changes in renal function was low (<1%). However, this result should be interpreted with caution as data on renal function results were sparse (unregistered data for renal failure up to 77.9%). In fact, a study aiming to report CKD prevalence and recognition in a Swedish healthcare cohort showed that registration of CKD diagnosis was suboptimal, with only 12% of affected patients having an ICD‐10 related diagnostic code.49 However, we suspect these unregistered values are more likely to reflect less severe impairment. Moreover, not all reasons for dose changes are registered in the different databases and we only considered those during the treatment episode. Therefore, patients appropriately dosed at the index date, without any further dose changes, are not considered as adjusted. The discrepancy between the proportion of patients with changes in tablet strengths and the low proportion of patients with age and CKD related adjustments might be due to patients with an increase in tablet strength not being accounted for. Other studies have reported about 20% patients receiving inappropriate doses, most often too low (38%) or excessively high dose (22%).14, 15

4.6. Strengths

The main strength of this study is the large number of patients providing real‐world data about incidence, concomitant use of potentially interacting drugs and dose adjustments. In addition, the use of a standardized protocol across the different databases supports the interpretation and comparability of results from selected countries. Disease and drug codes were harmonized, the study results were blinded and only shared with the whole consortium after each centre had completed their analysis, avoiding some information bias and promoting independent results. The consented and broad definition of the inclusion criteria ensures the generalisability of the results as all the new users with a diagnosis of NVAF were presumably included. In addition, the performance of a sensitivity analysis excluding patients with multiple potential DOAC indications gave similar results for most of the main variables. This supports the results of the main analysis with respect to closeness to real‐life DOAC use, since several indications might be present in addition to NVAF.

4.7. Limitations

There was large case mix in the databases, which made comparisons between countries difficult. In addition, there are differences in population coverage among the databases. Only 1 database includes the total reference population (DNR), while others are considered representative samples of the national populations when considering age, sex and geographical distribution (UK/CPRD, Spain/BIFAP and SIDIAP, France/EGB, Mondriaan). The inclusion of nonrepresentative databases with population coverages under 90% (German databases) must be considered when extending the results to the whole population. Since we used prescription, dispensing or reimbursement data that do not have complete information on actual drug intake, there might have been certain degree of drug use misclassification, common to all clinical studies, even randomized trials. In addition, drugs prescribed by physicians, other than general practitioners, could be missed when using prescribing databases as these are commonly general practice databases.

A drop in the number of patients was observed in some databases (Figure S1). This may be related to the fact that DOACs can be used for a variety of diagnoses. Although some patients with NVAF may have been lost in this process, the criteria ensure that we can be certain all patients included in the analysis do indeed have NVAF.

Information on the indication associated with the prescription might also be incomplete. For example, a definite linkage between compound and indication is lacking in most of the databases hence, we used the term potential indications. Additionally, some data sources include data from hospital admissions and contacts (DNR), while others include exclusively general practice encounters. Codes used in diagnosis were not specifically validated in this study but outcome validation has been performed in other studies showing high validity.19, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57 Laboratory values were not documented in some databases so codes for renal impairment (including somewhat nonspecific renal impairment codes) were used. This broad definition may explain the high proportion of patients with CKD found in some databases. Dose adjustment related to change in renal function and age was only assessed if a change in dose was associated with a change in renal function or in age; however, we did not assess if changes in renal function were subsequently followed by changes in dose. Moreover, a dose adjustment was defined as switching from 1 tablet strength to another of the same active substance. This definition precludes assessing posology changes that may have taken place without changing tablet strengths. Regarding potential interactions, lacking documentation of over the counter medications might be relevant, in particular for some NSAIDS, low‐dose acetylsalicylic acid (mainly pharmacodynamic interactions) and St John's Wort (pharmacokinetic interaction).

In conclusion, this study shows an increased incidence of use of DOACs related to NVAF in the study period across 6 European countries. In 2015, the incidence of DOAC use ranged from 8.7 per 10 000 in Spain to 27.6 per 10 000 in Denmark, with a higher incidence in men than in women, especially in patients ≥75 years. Potential use of contraindicated drugs, such as other anticoagulants, in some countries raises concerns about potential haemorrhagic risk. Finally, the proportion of dose adjustment related to changes in renal function or age deserves a more complete approach. The differences among the countries might be explained by different national or regional recommendations, prescription patterns and characteristics of the selected databases. Drug utilization studies based on several databases across different countries using a standard protocol may help to compare drug use and identify sources of variation, enabling health care decisions and supporting the rational use of medicines.

COMPETING INTERESTS

N.M.: Bordeaux PharmacoEpi has done 2 postauthorisation studies of comparative effectiveness and safety of DOAC compared to VKA, requested by the French regulatory authorities and financed by the respective marketing authorisation holders. These studies do not concern drug utilisation and do not represent a conflict of interest.

O.K. has provided an educational lecture (nonproduct related) for Roche in May 2017.

M.An. reports research grants from AstraZeneca, H. Lundbeck & Mertz, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Nycomed, and Pfizer, received by the institutions at which he has been employed. M.An. has received fees for organising and teaching pharmacoepidemiology courses at Medicademy, the Danish Association for the Pharmaceutical Industry. M.An.'s professorship is supported by a grant from the Novo Nordisk Foundation to the University of Copenhagen (NNF15SA0018404).

CONTRIBUTORS

All other authors participated in the conception and design, interpretation of data, and revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

L.I. participated in the conception and design, interpretation of data, and writing the paper. M.S. participated in the conception and design, interpretation of data and writing the paper. X.V. participated in the design, data analysis of SIDIAP database. E.B. participated in the conception and design, data analysis of SIDIAP database. M.R. participated in the design, data analysis of Bavarian database. S.S. and A.H. participated in the design, data analysis of AOK Nordwest database. C.H., E.M.M., D.M. and L.M. L.‐M. participated in the design, data analysis of BIFAP database. C.G. participated in the conception and design, interpretation of data. N.M., C.D. and R.L. participated in the design, data analysis of EGB database. M.Aa., M.An. and M.L.D.B. participated in the design, data analysis of DNR data. R.G., R.v.d.H. and P.S. participated in the design, data analysis of Mondriaan and CPRD databases. O.K. and H.G. coordinated the whole project.

5.

Supporting information

TABLE S1 Marketing dates for the different types of direct oral anticoagulant drugs in the participating countries.

TABLE S2 Codes used to identify the study population and drugs of study

TABLE S3 Codes used to identify concomitant drugs

TABLE S4 Codes used to identify comorbidities

TABLE S5 Renal function at baseline and dose adjustment for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs new users

TABLE S6 Standardised incidences for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs and database (new users per 10 000 people)

TABLE S7 Crude incidences for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs and database (new users per 10 000 people)

TABLE S8 Standardised incidences by individual direct oral anticoagulant drug in each database (new users per 10 000 people)

TABLE S9 Crude incidences by individual direct oral anticoagulant drug in each database (new users per 10 000 people)

TABLE S10 Baseline characteristics for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs new users with diagnosis of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and without other direct oral anticoagulant drug indication.

TABLE S11 Concomitant treatment during the first treatment episode for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs new users with diagnosis of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and without other direct oral anticoagulant drug indication

TABLE S12 Renal function at baseline and dose adjustment for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs new users with diagnosis of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and without other direct oral anticoagulant drug indication

FIGURE S1 Flowcharts

FIGURE S2 Crude incidences by individual direct oral anticoagulant drug in each database

FIGURE S3 Standardized incidence of all direct oral anticoagulant drugs by sex in each database

FIGURE S4. Incidences for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs by age and sex in each database

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The research leading to these results was conducted as part of the activities of the PE‐PV Consortium (Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacovigilance Consortium), which is a public academic partnership coordinated by the University of Utrecht. The project has received support from the European Medicines Agency under the Framework service contract (nr EMA/2015/27/PH) with regard to the reopening of competition no3.

K. Janhsen (Witten/Herdecke University, Alfred‐Herrhausen‐Straße 50, 58448 Witten, Germany (UW/H)) and B. Grave (AOK NORDWEST, Kopenhagener Straße 1, 44269 Dortmund, Germany). R. Gerlach and M. Tauscher (National Association of Statutory Health Insurance Physicians of Bavaria, Elsenheimerstr. 39, D‐80687 Munich, Germany).

The authors of the BIFAP database would like to acknowledge the excellent collaboration of the primary care general practitioners and pediatricians, and also the support of the regional governments to the database. This study is based in part on data from the BIFAP fully financed by the Spanish Agency on Medicines and Medical Devices (AEMPS).

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the EMA (European Medicines Agency) or one of its committees or working parties, or AEMPS (Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios).

Ibáñez L, Sabaté M, Vidal X, et al. Incidence of direct oral anticoagulant use in patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and characteristics of users in 6 European countries (2008–2015): A cross‐national drug utilization study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2019;85:2524–2539. 10.1111/bcp.14071

The authors confirm that the Principal Investigator for this paper is Luisa Ibáñez and that she had direct clinical responsibility for patients.

Data Availability Statement:The data that support the findings of this study are available from third party (data owners). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the authors with the permission of third party.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from third party (data owners). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the authors with the permission of third party.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kirchhof P, Benussi S, Kotecha D, et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2893‐2962. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Björck S, Palaszewski B, Friberg L, Bergfeldt L. Atrial fibrillation, stroke risk, and warfarin therapy revisited: a population‐based study. Stroke. 2013;44(11):3103‐3108. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Haim M, Hoshen M, Reges O, Rabi Y, Balicer R, Leibowitz M. Prospective national study of the prevalence, incidence, management and outcome of a large contemporary cohort of patients with incident non‐valvular atrial fibrillation. J am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(1):e001486 10.1161/JAHA.114.001486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stewart S, Hart CL, Hole DJ, McMurray JJ. A population‐based study of the long‐term risks associated with atrial fibrillation: 20‐year follow‐up of the Renfrew/Paisley study. Am J Med. 2002;113(5):359‐364. 10.1016/s0002-9343(02)01236-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hart RG, Pearce LA, Aguilar MI. Meta‐analysis: antithrombotic therapy to prevent stroke in patients who have nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(12):857‐867. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-12-200706190-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ruff CT, Giugliano RP, Braunwald E, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants with warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation: a meta‐analysis of randomised trials. Lancet (London, England). 2014;383(9921):955‐962. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62343-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Larsen TB, Rasmussen LH, Skjøth F, et al. Efficacy and safety of dabigatran etexilate and warfarin in “real‐world” patients with atrial fibrillation: a prospective nationwide cohort study. J am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(22):2264‐2273. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giner‐Soriano M, Roso‐Llorach A, Vedia Urgell C, et al. Effectiveness and safety of drugs used for stroke prevention in a cohort of non‐valvular atrial fibrillation patients from a primary care electronic database. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(1):97‐107. 10.1002/pds.4137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Komen J, Forslund T, Hjemdahl P, Andersen M, Wettermark B. Effects of policy interventions on the introduction of novel oral anticoagulants in Stockholm: an interrupted time series analysis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(3):642‐652. 10.1111/bcp.13150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hellfritzsch M, Husted SE, Grove EL, et al. Treatment changes among users of non‐vitamin K antagonist Oral anticoagulants in atrial fibrillation. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2017;120(2):187‐194. 10.1111/bcpt.12664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Becattini C, Franco L, Beyer‐Westendorf J, et al. Major bleeding with vitamin K antagonists or direct oral anticoagulants in real‐life. Int J Cardiol. 2017;227:261‐266. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.11.117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Maura G, Pariente A, Alla F, Billionnet C. Adherence with direct oral anticoagulants in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation new users and associated factors: a French nationwide cohort study. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(11):1367‐1377. 10.1002/pds.4268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Loo SY, Dell'Aniello S, Huiart L, Renoux C. Trends in the prescription of novel oral anticoagulants in UK primary care. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83(9):2096‐2106. 10.1111/bcp.13299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shrestha S, Baser O, Kwong WJ. Effect of renal function on dosing of non‐vitamin K antagonist direct Oral anticoagulants among patients with Nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. Ann Pharmacother. 2017;52(2):147‐153. 10.1177/1060028017728295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Pattullo CS, Barras M, Tai B, McKean M, Donovan P. New oral anticoagulants: appropriateness of prescribing in real‐world setting. Intern Med J. 2016;46(7):812‐818. 10.1111/imj.13118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Desmaele S, Steurbaut S, Cornu P, Brouns R, Dupont AG. Clinical trials with direct oral anticoagulants for stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation: how representative are they for real life patients? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;72(9):1125‐1134. 10.1007/s00228-016-2078-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ho P, Brooy BL, Hayes L, Lim WK. Direct oral anticoagulants in frail older adults: a geriatric perspective. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2015;41(4):389‐394. 10.1055/s-0035-1550158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smeets HM, Kortekaas MF, Rutten FH, et al. Routine primary care data for scientific research, quality of care programs and educational purposes: the Julius general Practitioners' network (JGPN). BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):735 10.1186/s12913-018-3528-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schmidt M, Schmidt SAJ, Sandegaard JL, Ehrenstein V, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish National Patient Registry: a review of content, data quality, and research potential. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:449‐490. 10.2147/CLEP.S91125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kildemoes HW, Sørensen HT, Hallas J. The Danish National Prescription Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39(Suppl 7):38‐41. 10.1177/1403494810394717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schmidt M, Pedersen L, Sørensen HT. The Danish civil registration system as a tool in epidemiology. Eur J Epidemiol. 2014;29(8):541‐549. 10.1007/s10654-014-9930-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Jaunzeme J, Eberhard S, Geyer S. [How “representative” are SHI (statutory health insurance) data? Demographic and social differences and similarities between an SHI‐insured population, the population of Lower Saxony, and that of the Federal Republic of Germany using the example of the AOK in Lower Saxony] Wie “repräsentativ” Sind GKV‐Daten? Bundesgesundheitsblatt ‐ Gesundheitsforsch ‐ Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56(3):447‐454. 10.1007/s00103-012-1626-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hoffmann F, Koller D. Verschiedene Regionen, verschiedene Versichertenpopulationen? Soziodemografische und gesundheitsbezogene Unterschiede zwischen Krankenkassen. Das Gesundheitswes. 2015;79(1):e1‐e9. 10.1055/s-0035-1564074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mehring M, Donnachie E, Schneider A, et al. Impact of regional socioeconomic variation on coordination and cost of ambulatory care investigation of claims data from Bavaria, Germany. BMJ Open. 2017;7(10):e016218 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. de Abajo FJ, Gil MJ, Bryant V, Timoner J, Oliva B, García‐Rodríguez LA. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with NSAIDs, other drugs and interactions: a nested case‐control study in a new general practice database. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;69(3):691‐701. 10.1007/s00228-012-1386-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. García‐Gil Mdel M, Hermosilla E, Prieto‐Alhambra D, et al. Construction and validation of a scoring system for the selection of high‐quality data in a Spanish population primary care database (SIDIAP). Inform Prim Care. 2011;19(3):135‐145. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22688222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Williams T, van Staa T, Puri S, Eaton S. Recent advances in the utility and use of the general practice research database as an example of a UK primary care data resource. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2012;3(2):89‐99. 10.1177/2042098611435911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Herrett E, Gallagher AM, Bhaskaran K, et al. Data resource profile: clinical practice research datalink (CPRD). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(3):827‐836. 10.1093/ije/dyv098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bezin J, Duong M, Lassalle R, et al. The national healthcare system claims databases in France, SNIIRAM and EGB: powerful tools for pharmacoepidemiology. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. September 2016;2017(8):1‐9. 10.1002/pds.4233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. EMA . Http://www.Encepp.eu/encepp/viewResource.htm?id=2441. in Each Database. R. ENCePP Protocol Register. Accessed August 8, 2019.

- 31. Gardarsdottir H, Souverein PC, Egberts TCG, Heerdink ER. Construction of drug treatment episodes from drug‐dispensing histories is influenced by the gap length. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63(4):422‐427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Eurostat . http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/population-demography-migration-projections/population-data/database. Accessed May 16, 2018.

- 33. Harding SD, Sharman JL, Faccenda E, et al. The IUPHAR/BPS guide to PHARMACOLOGY in 2018: updates and expansion to encompass the new guide to IMMUNOPHARMACOLOGY. Nucl Acids Res. 2018;46:D1091‐D1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alexander SPH, Fabbro D, Kelly E, et al. The Concise Guide to PHARMACOLOGY 2017/18: enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2017;174:S272‐S359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mueller T, Alvarez‐Madrazo S, Robertson C, Bennie M. Use of direct oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation in Scotland: applying a coherent framework to drug utilisation studies. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26(11):1378‐1386. 10.1002/pds.4272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Olesen JB, Sørensen R, Hansen ML, et al. Non‐vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulation agents in anticoagulant naïve atrial fibrillation patients: Danish nationwide descriptive data 2011‐2013. Europace. 2015;17(2):187‐193. 10.1093/europace/euu225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M, Nichols M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(42):3232‐3245. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vlahović‐Palcevski V, Wetermark B, Ibáñez L, Vander Stichele R. Comparison of drug utilization across different geographical areas In: Elseviers M, ed. Drug Utilization Research. Methods and Applicationsfirst. Chichester, West Susex, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2016:153‐159. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rodríguez‐Bernal CL, Hurtado I, García‐Sempere A, Peiró S, Sanfélix‐Gimeno G. Oral anticoagulants initiation in patients with atrial fibrillation: real‐world data from a population‐based cohort. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:63 10.3389/fphar.2017.00063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Desai NR, Krumme AA, Schneeweiss S, et al. Patterns of initiation of Oral anticoagulants in patients with atrial fibrillation— quality and cost implications. Am J Med. 2014;127(11):1075‐1082.e1. 10.1016/J.AMJMED.2014.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Reinhold T, Rosenfeld S, Müller‐Riemenschneider F, et al. Patienten mit Vorhofflimmern in Deutschland. Herz. 2012;37(5):534‐542. 10.1007/s00059-011-3575-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Michelena HI, Powell BD, Brady PA, Friedman PA, Ezekowitz MD. Gender in atrial fibrillation: ten years later. Gend Med. 2010;7(3):206‐217. 10.1016/j.genm.2010.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. EMA . https://www.ema.europa.eu/.

- 44. Hernandez I, Zhang Y, Saba S. Comparison of the effectiveness and safety of Apixaban, dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and warfarin in newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2017;120(10):1813‐1819. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2017.07.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Anselmino M, Battaglia A, Gallo C, et al. Atrial fibrillation and female sex. J Cardiovasc Med. 2015;16(12):795‐801. 10.2459/JCM.0000000000000239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gómez‐Doblas JJ, Muñiz J, Martin JJA, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation in Spain. OFRECE study results. Rev Española Cardiol (English Ed). 2014;67(4):259‐269. 10.1016/j.rec.2013.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Carnarius S, Heuer J, Stausberg J. Diagnosenkodierung in deutschen Arztpraxen aus klassifikatorischer Sicht: Eine retrospektive Studie mit Routinedaten. Das Gesundheitswes. 2018;80(11):1000‐1005. 10.1055/s-0043-125069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. OTC . Http://www.aesgp.eu/facts-Figures/otc-ingredients/?result=name&multiselect=none&country=15%23by-Parameter.

- 49. Gasparini A, Evans M, Coresh J, et al. Prevalence and recognition of chronic kidney disease in Stockholm healthcare. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2016;31(12):2086‐2094. 10.1093/ndt/gfw354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hartmann J, Weidmann C, Biehle R. Validation of SHI claims data exemplified by gender‐specific diagnoses. Gesundheitswesen. 2016;78(10):e53‐e58. 10.1055/s-0035-1565072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. García‐Poza P, de Abajo FJ, Gil MJ, Chacón A, Bryant V, García‐Rodríguez LA. Risk of ischemic stroke associated with non‐steroidal anti‐inflammatory drugs and paracetamol: a population‐based case‐control study. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(5):708‐718. 10.1111/jth.12855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ruigómez A, Brauer R, Rodríguez LAG, et al. Ascertainment of acute liver injury in two European primary care databases. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;70(10):1227‐1235. 10.1007/s00228-014-1721-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Maier B, Wagner K, Behrens S, et al. Comparing routine administrative data with registry data for assessing quality of hospital care in patients with myocardial infarction using deterministic record linkage. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):605 10.1186/s12913-016-1840-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. GKV‐Spitzenverband and BARMER. Bewertung der Kodierqualität von vertragsärztlichen Diagnosen. https://www.gkv-spitzenverband.de/media/dokumente/krankenversicherung_1/aerztliche_versorgung/verguetung_und_leistungen/klassifikationsverfahren/9_Endbericht_Kodierqualitaet_Hauptstudie_2012_12-19.pdf.

- 55. Giroud M, Hommel M, Benzenine E, Fauconnier J, Béjot Y, Quantin C. Positive predictive value of French hospitalization discharge codes for stroke and transient ischemic attack. Eur Neurol. 2015;74(1–2):92‐99. 10.1159/000438859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Blin P, Dureau‐Pournin C, Lassalle R, Abouelfath A, Droz‐Perroteau C, Moore N. A population database study of outcomes associated with vitamin K antagonists in atrial fibrillation before DOAC. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016;81(3):569‐578. 10.1111/bcp.12807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Giner‐Soriano M, Vedia Urgell C, Roso‐Llorach A, et al. Effectiveness, safety and costs of thromboembolic prevention in patients with non‐valvular atrial fibrillation: phase I ESC‐FA protocol study and baseline characteristics of a cohort from a primary care electronic database. BMJ Open. 2016;6(1):e010144 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

TABLE S1 Marketing dates for the different types of direct oral anticoagulant drugs in the participating countries.

TABLE S2 Codes used to identify the study population and drugs of study

TABLE S3 Codes used to identify concomitant drugs

TABLE S4 Codes used to identify comorbidities

TABLE S5 Renal function at baseline and dose adjustment for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs new users

TABLE S6 Standardised incidences for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs and database (new users per 10 000 people)

TABLE S7 Crude incidences for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs and database (new users per 10 000 people)

TABLE S8 Standardised incidences by individual direct oral anticoagulant drug in each database (new users per 10 000 people)

TABLE S9 Crude incidences by individual direct oral anticoagulant drug in each database (new users per 10 000 people)

TABLE S10 Baseline characteristics for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs new users with diagnosis of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and without other direct oral anticoagulant drug indication.

TABLE S11 Concomitant treatment during the first treatment episode for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs new users with diagnosis of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and without other direct oral anticoagulant drug indication

TABLE S12 Renal function at baseline and dose adjustment for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs new users with diagnosis of nonvalvular atrial fibrillation and without other direct oral anticoagulant drug indication

FIGURE S1 Flowcharts

FIGURE S2 Crude incidences by individual direct oral anticoagulant drug in each database

FIGURE S3 Standardized incidence of all direct oral anticoagulant drugs by sex in each database

FIGURE S4. Incidences for all direct oral anticoagulant drugs by age and sex in each database

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from third party (data owners). Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the authors with the permission of third party.