Abstract

Background

Lip dose challenges (LDCs) are often performed as an initial step before oral food challenges (OFCs). However, guidance on how to perform and interpret LDCs is unclear, and data are lacking regarding the diagnostic accuracy of LDCs.

Objective

To investigate current practice with respect to LDCs among UK allergy health care professionals, and to evaluate the diagnostic utility of LDCs in children undergoing OFCs for IgE-mediated food allergy.

Methods

We used an electronic survey to assess the use of LDCs by UK Allergy clinics. Separately, we prospectively recruited children undergoing “low-risk” OFCs for suspected IgE-mediated food allergy from 2 large specialist allergy units in London. LDC was performed 30 minutes before the OFC, by applying the food to the inner lip for 30 seconds. Objective symptoms were considered a positive outcome. All patients subsequently proceeded to OFC regardless of LDC outcome, and outcome assessed according to PRACTALL consensus.

Results

We received 147 responses to the online survey, representing 67% of registered pediatric allergy clinics in the United Kingdom. Eighty percent of respondents (representing 81% of responding centers) included LDC as the first step of OFC in routine clinical practice. There was a wide variation in both how LDCs were performed and interpreted, with one-third not proceeding to OFC if LDC resulted in subjective symptoms. In the prospective study, 198 children (mean age, 7 years) with conclusive OFCs were included. Foods tested were tree nuts (30%), peanut (16.6%), egg (16%), fish (10.5%), milk (6%), shrimp (4%), and other (16.9%). There were 12 positive LDCs (1 of which triggered systemic symptoms: generalized urticaria) and 31 positive OFCs. Two children with positive LDCs went on to have a negative diagnostic OFC. Sensitivity of LDC was 32%, specificity 98%, with a false-negative rate of 68%.

Conclusions

Most UK allergy clinics included LDC as an initial step during OFC, despite a wide variation in how LDCs are performed and interpreted, which raises major concerns about the reproducibility and the validity of the test. We found that LDC had poor sensitivity as an alternative or initial step to formal OFC.

Key words: Food allergy, Children, Diagnosis, Oral food challenge, Lip dose, Labial challenge

Abbreviations used: LDC, Lip dose challenge; OFC, Oral food challenge

What is already known about this topic? Lip dose challenges (LDCs) may be common in clinical practice.

What does this article add to our knowledge? Most UK allergy centers include a lip dose as part of routine food challenge, with a wide variation in performance and interpretation, which impacts on test reproducibility and validity. The diagnostic utility of LDCs is limited.

How does this study impact current management guidelines? LDC is unlikely to confer any advantage if incorporated into routine oral food challenges, and may be associated with false positives and systemic reactions. Clinical guidelines should actively caution against the use of LDC in the diagnosis of food allergy.

Introduction

Oral food challenges (OFCs) remain the criterion standard for the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy.1, 2 Anecdotally, lip dose challenges (LDCs) (also referred to as labial challenges in the literature) appear to be commonplace in clinical practice in some countries, although guidance on how to perform and interpret LDCs is lacking. Monteret-Vautrin et al3 suggested an application time between 2 seconds and 10 minutes, a wide range that is likely to have an impact on outcome. Likewise, very subtle changes such as “smoothing of the lip” could be considered sufficient to indicate a positive LDC,3 which may lead to subjectivity in interpretation. There is a lack of data as to how the LDC correlates to the OFC outcome: previous studies assumed a diagnosis of food allergy on the basis of a positive LDC, without progressing to formal OFC to confirm the diagnosis.4, 5 Hourihane et al6 reported that a subset of patients with suspected peanut allergy and a positive LDC passed a subsequent OFC, raising a concern about the risk of false-positive LDCs. Accordingly, LDCs are not recommended in some guidelines on food allergy diagnosis or OFCs,2, 7 but are included as a first step in other protocols.8, 9

Given this variation in both practice and interpretation, we undertook a 2-phase study: first, to systematically assess the use of LDC, and investigate current practice and perceptions of LDC among health care professionals working in Pediatric Allergy in the United Kingdom; second, to evaluate the diagnostic utility of LDC compared with OFC outcomes in children undergoing diagnostic food challenge for suspected IgE-mediated food allergy.

Methods

Survey of health care professionals

We undertook a web-based survey among health care professionals who were members of the Paediatric Allergy Interest Group of the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. The content of the questionnaire is presented in Table E1 in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org. Briefly, it covered respondents' demographic characteristics, professional experience, and perception of LDC utility in clinical practice. Also, respondents were asked how they would perform LDC for a fluid, semisolid, and solid food (ie, milk, peanut butter, and cashew, respectively) and how they would interpret the LDC outcome (ie, whether a given manifestation would be considered a positive outcome and whether food allergy diagnosis would be assumed with no need for further OFC).

Prospective assessment of false positives/negatives associated with LDC

In the second phase of the study, children undergoing open OFC for suspected IgE-mediated food allergy were recruited prospectively from 2 large specialist allergy units in London (St Mary's Hospital [Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust] and the Royal London Hospital [Barts Health NHS Trust]), from June to December 2015. Clinical data were registered including age, atopic dermatitis, other food allergies, food tested at OFC, skin prick test result to the tested food, and whether the suspected diagnosis was based on previous reaction or sensitization only. Skin prick testing was performed according to standard guidelines, with histamine 10 mg/mL as a positive control.10 OFC were performed because of indeterminate allergic status—either a reducing skin prick test in the context of possible resolution, level of sensitization less than 95% positive predictive values, or more than 95% predictive value but with an absence of previous reaction or with evidence of possible tolerance.

LDC was performed in all subjects 30 minutes before OFC. A small pea-sized amount of the allergen in question was applied to the border of the inner and outer lip and the patient observed for 30 minutes; we chose this time interval to be consistent with the dosing interval used for OFC, although existing LDC protocols use a 20-minute interval.8, 9 We used a liquid/paste (eg, nut butter) for application; where this was not possible due to the nature of the food, the lip was gently rubbed with the allergen in question for 10 seconds. The following objective symptoms following LDC were considered a positive outcome: erythema, urticaria, and/or angioedema at the application site or systemic skin, gastrointestinal, respiratory, or cardiovascular symptoms. Subjective symptoms were not used as indicative of a positive LDC.

All subjects then proceeded to open OFC regardless of the LDC outcome, except where the LDC resulted in a systemic reaction that would qualify as a positive result in an OFC. Children were fed incremental doses of the allergen in question, up to a top dose of 3 g protein equivalent, at 30-minute intervals. The challenge was halted at onset of objective clinical symptoms, in line with PRACTALL criteria,1 unless consent was withdrawn previously. Children were observed for a further 2 hours following the last dose. Each OFC was documented on a standardized proforma, and outcome reviewed independently by 2 authors (M.V.O., P.J.T.) according to the PRACTALL consensus.1 Children with inconclusive OFC (eg, OFC halted before reaching PRACTALL stopping criteria) were excluded from analysis.

LDC was already included in the existing clinical protocols at both sites; thus, the study involving patients was considered a clinical service evaluation. Our local Research Ethics Committee advised that this did not require ethical approval, because no changes were required in relation to routine practice.

Data analysis

The OFC outcome was used as the reference parameter to calculate the diagnostic performance of the LDC, together with 95% CIs according to the efficient-score method (corrected for continuity) outlined by Newcombe.11 Given our interest in assessing the risk of false positives associated with LDC, we used the method of Carley et al12 to determine that a sample size of approximately 220 would be sufficient to allow us to estimate the specificity of LDC within 10% of that for OFC with probability of finding a false-positive result at 5% or less. Fisher Exact test was used for comparative analysis of clinical data between children having positive and negative LDC, except for continuous variables for which Mann-Whitney U test was used. PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill) was used for analysis.

Results

Perception and use of LDCs by health care professionals in the United Kingdom

One hundred forty-seven respondents completed the questionnaire, which represented 67% (53 of 79) of British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology–registered pediatric allergy clinics in the United Kingdom. Of these respondents, 88 (60%) were doctors, 51 (32%) specialist nurses, and 8 (5%) dietitians. The vast majority worked in specialist allergy clinics and district general hospitals (48% and 50%, respectively), with 67% working exclusively in the pediatric setting. Overall responses are presented in Table E1.

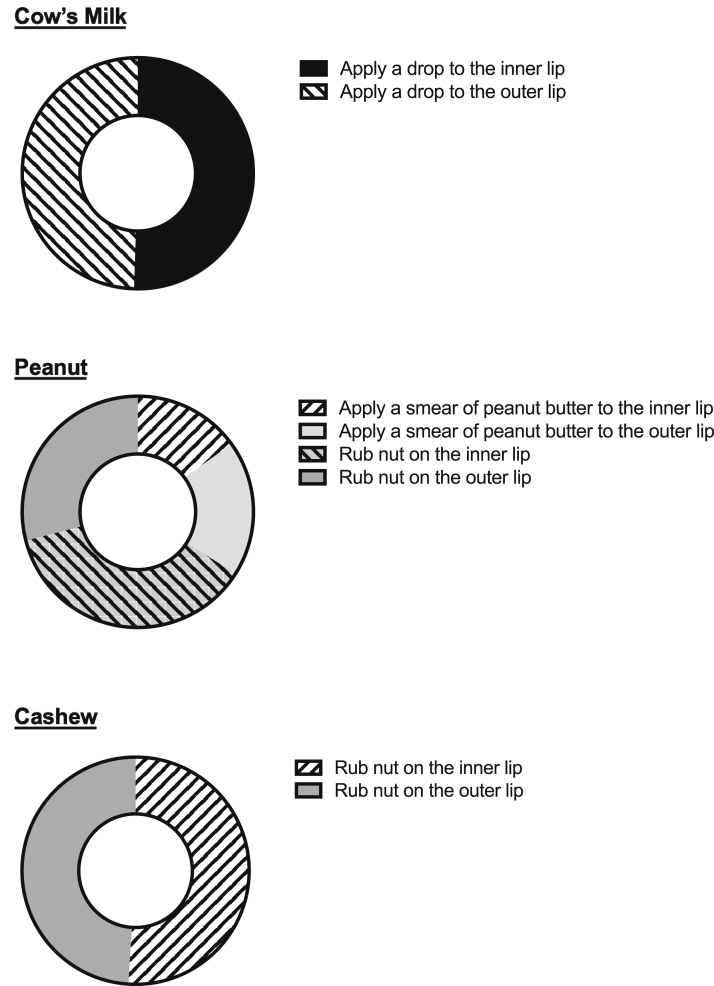

Most respondents (71%, 102 of 147) reported that in their opinion, LDCs were a useful first step when performing an OFC. Eighty percent (117 of 147), representing 81% of responding centers, included LDC as a first step in an OFC in routine clinical practice. There was a wide variation in how LDCs were performed, depending on the nature of then food being tested: in particular, there was significant disagreement on whether to apply the food to the inner lip or the outer lip (Figure 1). With respect to the interpretation of LDC, a (subjective) itchy lip or mouth was considered a positive finding by 37% of respondents, erythema at the application site by 46%, and urticaria/angioedema at the application site by 93%. Interestingly, the occurrence of urticaria away from the site of application was considered a positive finding by fewer respondents: 74% if on the face but away from the application site, and 70% if present on the body. There was also significant variation in interpreting outcomes from LDC: 17% and 31% would not proceed to a formal OFC in the presence of oral itch or local erythema, respectively, in contrast to more objective symptoms where most respondents would stop the challenge test and interpret LDC as indicative of food allergy (Table I).

Figure 1.

Technique of application for fluid (milk), semisolid (peanut butter), and solid food (cashew) for LDC, as reported by respondents.

Table I.

Interpretation of subjective and objective symptoms at LDC

| Symptom | STOP the challenge | CONTINUE with oral challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Oral pruritus or itchy lip | 17% | 83% |

| Erythema at the site of application | 31% | 69% |

| Urticaria and/or local angioedema at the site of application | 88% | 13% |

| Urticaria/angioedema on face, but remote from the site of application | 93% | 7% |

| Urticaria elsewhere (not on face) | 93% | 7% |

Diagnostic performance of LDC in relation to OFC outcomes

Two hundred twenty children were prospectively recruited for the study, 22 of whom were excluded because of an inconclusive OFC outcome, leaving 198 for analysis. Patients' demographic characteristics are presented in Table II. Twelve children had a positive LDC: 10 with objective skin symptoms at the application site, 1 with facial urticaria, and another who developed generalized urticaria. The OFC was positive in 31 cases, including 10 cases of anaphylaxis with lower respiratory symptoms. Ten of these 31 children (2 of 10 anaphylaxis reactions) had a positive LDC to egg (2), cow's milk (1), peanut (1), cashew (2), hazelnut (1), salmon (1), chickpea (1), and prawn (1). In these children with both a positive LDC and OFC, 5 reacted to the top dose (∼3 g protein) while 3 reacted to the first dose of the OFC. Two children with positive LDCs went on to have a negative diagnostic OFC (one to egg, the other to sardine fish), giving a false-discovery rate (the probability of a false positive if LDC is positive) of 17% (2 of 12). Diagnostic characteristics of the LDC are presented in Table III. There were no significant associations between LDC outcome and age (P = .17), skin prick test result (P = .053), having atopic dermatitis (P = .58), the particular food tested (P = .80), or in those with a positive OFC, the eliciting dose (P = .88) or the occurrence of anaphylaxis (P = .24) (see Table E2 in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org).

Table II.

Patient characteristics undergoing LDC/OFC (n = 220)

| Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age (y), median (range) | 6.0 (0.4-18) |

| Skin prick test (mm), median, (range) | 2 (0-10) |

| • Sensitization ≥2 mm | 148 (67) |

| Atopic eczema | 80 (36) |

| Other documented food allergies | 207 (94) |

| Food being tested at OFC: | |

| • Tree nuts | 66 (30) |

| ○ Hazelnut | 21 (10) |

| ○ Almond | 14 (6) |

| ○ Cashew | 12 (5) |

| ○ Walnut | 11 (5) |

| ○ Other | 9 (4) |

| • Peanuts | 36 (16) |

| • Egg | 35 (16) |

| • Fish | 23 (10) |

| • Cow's milk | 13 (6) |

| • Prawn/shrimp | 9 (4) |

| • Other | 37 (17) |

| Previous reaction to food being tested | 71 (32) |

Values are n (%) unless otherwise indicated.

Table III.

Diagnostic properties of the LDC in relation to OFC outcome in 198 children with suspected IgE-mediated food allergy

| Diagnostic properties of LDC | Value |

|---|---|

| True negative (no. of patients) | 165 |

| True positive (no. of patients) | 10 |

| False negative (no. of patients) | 21 |

| False positive (no. of patients) | 2 |

| Specificity (%, 95% CI) | 98% (95.3-99.8) |

| Sensitivity (%, 95% CI) | 32% (17.3-51.5) |

| Positive predictive value (%, 95% CI) | 83% (50.9-97.0) |

| Negative predictive value (%, 95% CI) | 89% (83.0-92.7) |

| Positive likelihood ratio | 26.9 |

| Negative likelihood ratio | 0.69 |

| False-negative rate | 68% |

| False-positive rate | 1.2% |

Discussion

Our data indicate that LDCs are used by most UK pediatric allergy centers as part of their food challenge protocols, despite a lack of evidence on their diagnostic value. We found wide variation in how LDCs are performed and interpreted by health care professionals, which raises major concerns about the reproducibility and the validity of the test. We subsequently evaluated the diagnostic utility of LDCs in a representative clinical cohort, and demonstrated a relatively poor correlation between the outcome of the LDC and the OFC itself.

In our cohort, a positive LDC was uncommon, even in those cases with a positive OFC. Thus, the sensitivity of LDC is low. Where LDC was positive, this was associated with a low false-positive rate and a high positive likelihood ratio, although we observed 2 cases where LDC was positive but participants went on to tolerate the food being tested at OFC, without reaction. These observations lead us to question the value of LDC in clinical practice, especially given the concerns regarding heterogeneity in test performance and interpretation: a high positive likelihood ratio is unlikely to change posttest probability in patients likely to be clinically allergic (and therefore already have a high pretest probability),13 while the false-discovery rate (17% in our cohort) despite the use of objective criteria to assess LDC implies a need to proceed to OFC irrespective of LDC outcome.

Our findings with respect to false-positive LDC are consistent with the observations of Hourihane et al.6 Venter et al14 also assessed the diagnostic utility of LDC, and found that all 9 of 13 patients with a positive LDC also had a positive OFC; however, 4 children did not proceed to formal food challenge. Both Rance and Dutau4 and ourselves observed children who developed systemic symptoms following LDC; thus, the same safety measures should be in place for LDC as for routine OFC. It is therefore difficult to see how incorporating LDC before OFC might be cost-effective, given the low positive rate and the precautions required because of risk of systemic reaction. In addition, the inclusion of LDC prolongs the challenge test unnecessarily. We used objective criteria consistent with the PRACTALL consensus to determine the outcome of OFC, in contrast to previous studies. We therefore believe that our data provide evidence against the use of LDC during OFC and certainly as an alternative to OFC, due to relatively poor diagnostic utility (in part because of a lack of clarity over test interpretation), as well as the potential for systemic reactions.

Although our prospective assessment of LDC was limited by cohort size, our data are representative of children undergoing OFC in routine clinical practice, and our sample size is probably typical of the number of food challenges that may be undertaken by a medium-to large-size allergy service over a 1-year period. For example, a large tertiary allergy service in the United States undertook an average of 230 OFCs per annum, although this cohort had a positive OFC rate of 30%.15 The lower rate of positive OFC in our cohort implies a lower risk profile to included cases. Thus, the diagnostic characteristics of LDC generated in this study cannot necessarily be applied elsewhere, and although our cohort was sufficiently powered to assess specificity (and thus rate of false positives), we were underpowered to estimate sensitivity/positive predictive value as indicated by the lower precision of the estimates as seen in the 95% CIs for sensitivity/positive predictive value in Table III. In routine practice, outside the context of desensitization, OFCs are generally performed in patients in whom the degree of sensitization is less than that which predicts 95% likelihood of reaction. However, OFCs are increasingly undertaken in children with a higher likelihood of clinical allergy—for example, before the commencement of oral immunotherapy. In this context, it is possible that the false-positive rate would be slightly lower, although this does not negate the significance of a false-positive LDC as observed in this study. We would not recommend LDC as part of OFC before initiating oral immunotherapy, because in this context one should define an eliciting dose (which then allows response to treatment to be assessed) and not depend on LDC that is clearly associated with a false-positive rate.

Recent research has provided evidence for the earlier introduction of potential food allergens into the infant diet, to reduce the risk of developing food allergy.16 Although the associated guidelines do not suggest LDC,17 in our experience many health care professionals recommend LDC as an initial step in introducing foods such as peanut butter into the infant diet. We caution against this approach, given the lack of evidence in the literature and the false-discovery rate identified in this study.

In conclusion, current guidelines should counsel against the use of LDC in the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy, because there is no robust evidence that LDC is useful for diagnosis. Finally, units continuing to perform LDC either as part of routine protocols or at parental request should interpret any positive findings with care and preferably proceed to a routine OFC.

Acknowledgments

We thank our colleagues within the pediatric allergy teams at the Royal London and St Mary's Hospitals for their support.

Footnotes

M.V.-O. was supported by a Marie Skłodowska-Curie actions - Research Fellowship funded by the Commission of the European Communities (reference: 656878). P.J.T. was supported by a Clinician Scientist award funded by the UK Medical Research Council (reference MR/K010468/1). P.J.T. and M.V.-O. have received research support from the Department of Health through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre awards to Imperial College London Healthcare National Health Service (NHS) Trust. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NHS, NIHR, or the Department of Health.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Online Repository

Table E1.

Questions used in this survey and responses obtained

| Question | Response options | Responses obtained, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Q1. Please select your main role as a health professional. | Dietitian | 9 (5.7) |

| Medical doctor | 92 (58.2) | |

| Nurse/nurse practitioner | 51 (32.3) | |

| Other | 6 (3.8) | |

| Q2. A. If you are a dietitian, in what area of dietetics do you work? | General dietetics | 0 (0) |

| Pediatric dietetics | 5 (55.6) | |

| Specialist allergy dietetics | 4 (44.4) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | |

| Q2. B. If you are a doctor, please select which option best describes your medical practice. | Specialist in allergy/immunology | 41 (44.6) |

| Adult physician (hospital based) | 6 (6.6) | |

| General pediatrics | 39 (42.4) | |

| General practice | 4 (4.4) | |

| Other | 2 (2) | |

| Q2.C. If you are a nurse, please select the option which best describes your area of practice. | Specialist allergy nurse | 41 (80.4) |

| Pediatrics | 8 (15.7) | |

| Adult nursing | 2 (3.9) | |

| Community nurse/nurse in general practice | 0 (0) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | |

| Q3. Do you work in | A tertiary specialist allergy clinic | 67 (48) |

| District general hospital | 63 (49.6) | |

| Primary care facility | 3 (2.4) | |

| Q4. For how many years have you been performing food challenges yourself? | Over 10 y | 56 (37.1) |

| 5-10 y | 46 (30.5) | |

| Under 5 y | 37 (24.5) | |

| I am still in training | 12 (8) | |

| Q5. The patients I see are | All pediatric patients | 100 (86.7) |

| Mostly pediatric but some adult patients | 7 (4.7) | |

| About half pediatric and half adult patients | 2 (1.3) | |

| Mostly adult but some pediatric patients | 17 (11.3) | |

| All adult | 24 (16) | |

| Q6. How many food challenges does your unit perform every month, on average? | <5 per month | 41 (28) |

| 5-10 | 32 (21.9) | |

| 10-25 | 33 (22.6) | |

| 25-50 | 26 (17.8) | |

| More than 50 | 14 (9.6) | |

| Q7. Do you think “lip doses” are useful as a first step in performing a food challenge? | Yes | 101 (69.7) |

| No | 33 (22.8) | |

| Not sure | 11 (7.6) | |

| Q8. Do you (or your unit) ever use lip doses when doing a food challenge? | Yes | 117 (80.7) |

| Never | 28 (19.3) | |

| Q9. How do you perform a lip dose to cow's milk? | Apply a drop to the inner lip | 49 (45) |

| Apply a drop to the outer lip | 48 (44) | |

| Other | 12 (11) | |

| Q10. How do you perform a lip dose to peanut? | Apply a smear of peanut butter to the inner lip | 15 (13.8) |

| Apply a smear of peanut butter to the outer lip | 19 (17.4) | |

| Rub some peanut on the inner lip | 37 (33.9) | |

| Rub some peanut on the outer lip | 29 (29.6) | |

| Other | 9 (8.3) | |

| Q11. How do you perform a lip dose to cashew nut? | Rub some cashew on the inner lip | 50 (48.3) |

| Rub some cashew on the outer lip | 48 (44.4) | |

| Other | 10 (9.3) | |

| Q12. What do you consider to be a positive lip dose (tick all that apply)? | Patient complains of itchy lip or mouth | 38 (36.5) |

| Redness or erythema at the site of application of dose | 48 (46.2) | |

| Urticaria and/or swelling at the site of application | 97 (93.3) | |

| Urticaria/angioedema on the face, but away from the site of application | 77 (74) | |

| Urticaria on the body | 73 (70.2) | |

| Q13-17. If the following symptoms occurred to a lip dose, what would you do? | ||

| Q13. Patient complains of itchy lip or mouth | STOP the challenge, ie, not proceed to an oral dose | 18 (17.3) |

| CONTINUE with the challenge, ie, proceed to an oral dose | 86 (82.7) | |

| Q14. Redness or erythema at the site of application of dose | STOP the challenge, ie, not proceed to an oral dose | 32 (30.8) |

| CONTINUE with the challenge, ie, proceed to an oral dose | 72 (69.2) | |

| Q15. Urticaria and/or swelling at the site of application | STOP the challenge, ie, not proceed to an oral dose | 91 (87.5) |

| CONTINUE with the challenge, ie, proceed to an oral dose | 13 (12.5) | |

| Q16. Urticaria/angioedema on the face, but away from the site of application | STOP the challenge, ie, not proceed to an oral dose | 97 (93.3) |

| CONTINUE with the challenge, ie, proceed to an oral dose | 7 (6.7) | |

| Q17. Urticaria on the body | STOP the challenge, ie, not proceed to an oral dose | 97 (93.3) |

| CONTINUE with the challenge, ie, proceed to an oral dose | 7 (6.7) |

Table E2.

Comparative analysis between children with positive and negative LDCs (N = 198)

| Characteristic | LDC result |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | ||

| Age (y), median | 3.0 | 6.0 | .17 |

| Atopic dermatitis, n (%) | 6 (50) | 64 (34) | .58 |

| Skin prick test (mm), median | 3 | 2 | .053 |

| Food tried at challenge, n (%) | .80 | ||

| Tree nuts | 3 (25) | 58 (31) | |

| Peanut | 1 (8) | 32 (17) | |

| Egg | 3 (25) | 30 (16) | |

| Fish | 2 (16.7) | 18 (10) | |

| Cow's milk | 1 (8) | 11 (6) | |

| Prawn/shrimp | 0 (0) | 7 (4) | |

| Other | 2 (17) | 30 (16) | |

| Anaphylaxis at OFC (where OFC positive) | 2 of 10 (20) | 8 of 21 (38) | .24 |

References

- 1.Sampson H.A., Gerth van Wijk R., Bindslev-Jensen C., Sicherer S., Teuber S.S., Burks A.W. Standardizing double-blind, placebo-controlled oral food challenges: American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology-European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology PRACTALL consensus report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130:1260–1274. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muraro A., Werfel T., Hoffmann-Sommergruber K., Roberts G., Beyer K., Bindslev-Jensen C., on behalf of the EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines. Diagnosis and management of food allergy. Allergy. 2014;69:1008–1025. doi: 10.1111/all.12429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Monteret-Vautrin D. Advances in allergology and clinical immunology. In: Godard P., Bousquet J., Michel F., editors. The Proceedings of the Plenary Sessions and the Afternoon Symposia of the XVth European Congress of Allergology and Clinical Immunology. The Parthenon Publishing Group; Paris, France: 1992. pp. 473–483. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rance F., Dutau G. Labial food challenge in children with food allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1997;8:41–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1997.tb00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantani A. Comment on: Labial food challenge in children with food allergy. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 1998;9:103. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.1998.tb00311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hourihane J.O.’B., Kilburn S.A., Nordlee J.A., Hefle S.L., Taylor S.L., Warner J.O. An evaluation of the sensitivity of subjects with peanut allergy to very low doses of peanut protein: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled food challenge study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;100:596–600. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(97)70161-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Soares-Weiser K., Takwoingi Y., Panesar S.S., Muraro A., Werfel T., Hoffmann-Sommergruber K., on behalf of the EAACI Food Allergy and Anaphylaxis Guidelines Group The diagnosis of food allergy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2014;69:76–86. doi: 10.1111/all.12333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy. Food challenge protocols. http://allergy.org.au/images/stories/pospapers/ASCIA_food_allergy_challenge_protocols_Sept_2011.pdf Available from: Accessed January 2, 2019.

- 9.Irish Food Allergy Network Hospital-based food challenges. http://ifan.ie/secondary-care-and-hospitals/food-challenges-hospital/ Available from: Accessed January 2, 2019.

- 10.King R., on behalf on the British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology (BSACI) Paediatric skin prick testing—standard operating procedure. http://www.bsaci.org/_literature_121183/Paediatric_skin_prick_testing_guideline Available from: Accessed January 2, 2019.

- 11.Newcombe R.G. Two-sided confidence intervals for the single proportion: comparison of seven methods. Stat Med. 1998;17:857–872. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980430)17:8<857::aid-sim777>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carley S., Dosman S., Jones S.R., Harrison M. Simple nomograms to calculate sample size in diagnostic studies. Emerg Med J. 2005;22:180–181. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.011148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roberts G., Lack G. Diagnosing peanut allergy with skin prick and specific IgE testing. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1291–1296. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Venter C., Maslin K., Grundy J., Glasbey G., Dean T. Should lip dosing be reconsidered when performing open food challenges? Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2017;28:707–711. doi: 10.1111/pai.12765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta M., Grossmann L.D., Spergel J.M., Cianferoni A. Egg food challenges are associated with more gastrointestinal reactions. Children (Basel) 2015;2:371–381. doi: 10.3390/children2030371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Addendum Guidelines for the Prevention of Peanut Allergy in the United States: report of the NIAID-Sponsored Expert Panel. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:29–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bird J.A., Groetch M., Allen K.J., Bock S.A., Leonard S., Nowak-Wegrzyn A.H. Conducting an oral food challenge to peanut in an infant. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:301–311.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]