Case Report

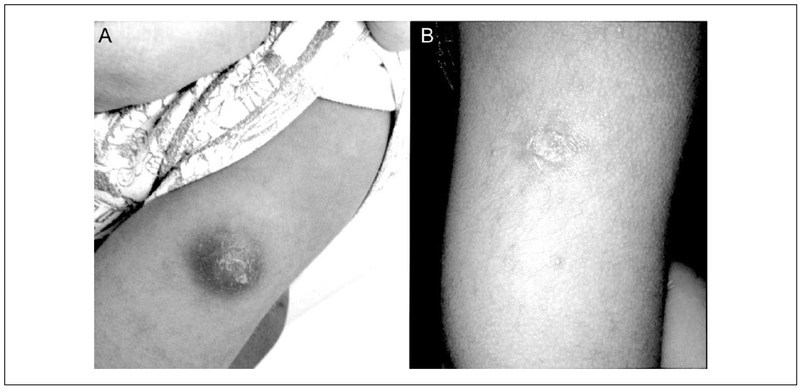

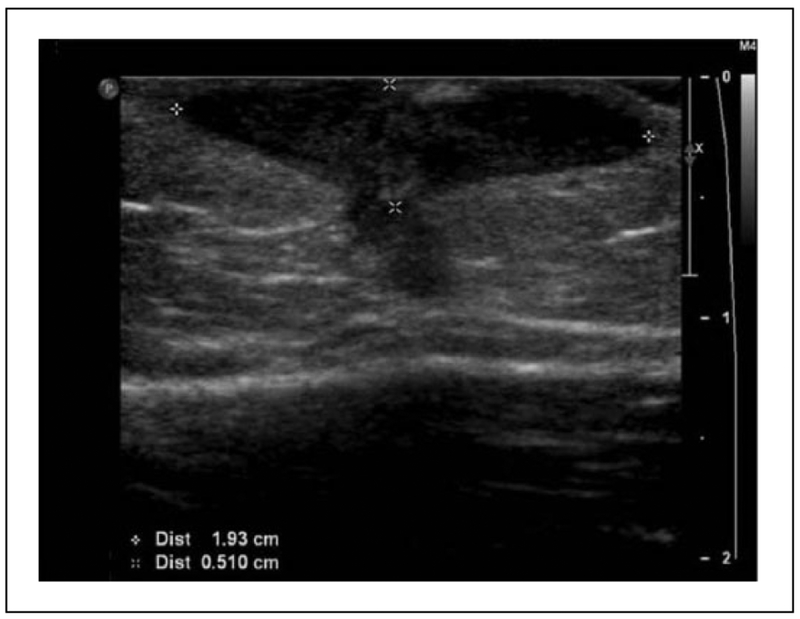

A previously healthy 3-year-old boy presented to the emergency department (ED) in Yale-New Haven Hospital with a chief complaint of prolonged swelling over the left deltoid. He was in good health until 5 months prior to presentation when, while visiting family in Brazil, he received the Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine over his left deltoid muscle. Within a few days of receiving the vaccine, his parents noted redness and swelling at the vaccine site that did not heal and slowly enlarged over several months. This swelling was associated with intermittent fever. His last fever was noted 2 weeks prior to presentation. It lasted for 5 days, with maximum temperature of 105°F. The swollen mass over his deltoid had sporadically drained yellow fluid but spontaneously stopped draining 1 week prior to presentation. The lesion was described as nontender unless palpated. There were no respiratory symptoms or bone pain. He reported no history of night sweats or weight loss. He had normal growth and development, and the parents denied a history of previous severe or frequent infections. On examination in the ED, he was noted to be afebrile with otherwise had normal vital signs. He had a 4.5 cm by 3.5 cm nodule with mild fluctuance on his left deltoid that was not tender or warm (Figure 1A). It was associated with shotty left axillary lymphadenopathy. An ultrasound examination obtained of this nodule revealed a hypoechoic collection just deep to the skin surface (Figure 2). This nodule underwent fine needle aspiration and the fluid was sent for acid-fast bacteria (AFB) culture. He was prescribed Isoniazid (INH) at a dose of 10 mg/kg daily and sent home with a plan for close follow up.

Figure 1.

Comparison of skin findings on (A) day of presentation and (B) 2-month follow-up.

Figure 2.

Two-dimensional ultrasound, sagittal view of deltoid revealing a 2.2 × 1.9 × 0.5 cm hypoechoic collection with 1.8-mm blind-ending sinus tract.

Final Diagnosis

Mycobacterium bovis-BCG strain abscess

Hospital Course

After 6 weeks of incubation, the AFB culture grew Mycobacterium bovis-BCG strain that was susceptible to streptomycin, isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol but resistant to pyrazinamide. After receiving INH for 2 months, he had significant improvement in the size and appearance of lesion (Figure 1B). He also reported no further fevers or wound drainage. He completed a total of 3 months of INH (until the lesion was only a healed nodule) with no complications (Figure 1B).

Discussion

The BCG vaccine is considered to be the most widely used vaccine in the world, with more than 10 million infants receiving it annually.1 Leon Calmette and Camille Guerin developed this vaccine in 1921 at the Pasteur Institute. The vaccine was developed from a live and virulent strain of Mycobacterium bovis from a cow with tuberculous mastitis. This particular strain was attenuated with 230 serial passages to another host, which resulted in a decrease in virulence when re-inoculated on the original host.2 Recent studies suggest that the loss of virulence occurred from a deletion of the RD1 region, which decreases tissue invasiveness, though the exact process by which this was originally accomplished is unknown.3

Many studies have been conducted to assess the efficacy of the BCG vaccine. Current data suggest that the vaccine is most effective at preventing tuberculous (TB) meningitis and miliary disease in children less than 5 years of age. On one of these sentinel studies, a randomized control trial, a 73% protection against active disease in infants living in Chicago was noted.4 Despite the effectiveness noted in children, studies on adolescents and adults show only 25% protection,5 and immunity wanes after 10 years.6 Given the low prevalence of TB in the United States, the effect of making interpretation of PPD testing more difficult and the minimal risk of an infant coming into contact with active TB, the BCG vaccine is not approved for routine use in the United States.

Currently there are 4 main strains that are derivatives of the original BCG, which account for more than 90% of the BCG vaccine use worldwide and include Pasteur strain 1173, Danish strain 1331, Glaxo strain 1077, and Tokyo strain 172. It has been proposed that the risks of adverse events from the BCG vaccine are directly related to the strain type, dose, concentration of live particles, and age of vaccination.7 Some particular formulations are thought to induce more adverse reactions—particularly the Pasteur strain.8 Despite this, serious adverse events from vaccination are thought to be fairly rare. Known adverse events are categorized by the World Health Organization as mild or severe. Mild events are thought to occur on almost all recipients. These are usually injection site reactions that can present as erythematous, indurated, and tender papules. The natural history of these papules is eventual ulceration and scarring that occurs after 2 to 5 months from vaccination. Severe adverse events are divided into local and systemic. Localized adverse events are the most common of the severe adverse events and include lymphadenitis (suppurated and nonsuppurated) and abscess. These have been described to occur at a frequency of 1 case per 1000 vaccinations.1,9 Severe and systemic complications include osteitis/osteomyelitis and disseminated BCG infection. These complications occur even more rarely, with recent estimates of 30 cases per 100 000 for osteitis and 5 cases per million recipients for disseminated BCG, which is thought to only occur in infants with a primary cellular immunodeficiency.10,11

Given the relative rarity of these severe adverse events and the lack of good clinical trials, the management of these complications has been controversial. Many experts recommend drainage of abscesses and antimycobacterial therapy in the setting of severe adverse events. A recent meta-analysis suggests that observation alone is the best course of action for nonsuppurated lymphadenitis, as these infections tend to regress without complication. On the other hand, this study suggested that needle aspiration and local instillation of INH would shorten recovery time in BCG-induced suppurated lymphadenitis and abscess.12 For systemic complications such as in osteitis and in disseminated disease, most data suggest a combination of both surgical and prolonged antimycobacterial therapy in the order of 6 to 12 months.13 We elected to give INH as there had not been healing in the previous 5 months.

Conclusions

Despite the fact that the BCG vaccine is the most widely used vaccine in the world, it is not approved in the United States for prevention of tuberculosis and therefore the complications of its use are seldom seen. Serious adverse events such as suppurative lymphadenitis, abscess, osteitis, and disseminated infection are rare but often require intervention and close outpatient follow-up.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. BCG vaccine. WHO position paper. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2004;79(4):27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Calmette A, Guerin C. Sur quelques propriétés du bacille tuberculeux d’origine, cultivé sur la bile de boeuf glycérinée. C R Acad Sci. 1909;149:716–718. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hsu T, Hingley-Wilson SM, Chen B, et al. The primary mechanism of attenuation of bacillus Calmette-Guerin is a loss of secreted lytic function required for invasion of lung interstitial tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12420–12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenthal SR, Loewinsohne, Graham ML, Liveright D, Thorne G, Johnson V. BCG vaccination against tuberculosis in Chicago. A twenty-year study statistically analyzed. Pediatrics. 1961;28:622–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereira SM, Barreto ML, Pilger D, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of first BCG vaccination against tuberculosis in school-age children without previous tuberculin test (BCG-REVAC trial): a cluster-randomized trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:300–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rodrigues LC, Mangtani P, Abubakar I. How does the level of BCG vaccine protection against tuberculosis fall over time? BMJ. 2011;343:d5974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamamoto S, Yamamoto T. Historical review of BCG vaccine in Japan. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2007;60:331–336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Milstien JB, Gibson JJ. Quality control of BCG vaccine by WHO: a review of factors that may influence vaccine effectiveness and safety. Bull World Health Organ. 1990;68:93–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lotte A, Wasz-Hockert O, Poisson N, Dumitrescu N, Verron M, Couvet E. BCG complications. Estimates of the risks among vaccinated subjects and statistical analysis of their main characteristics. Adv Tuberc Res. 1984;21: 107–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lotte A, Wasz-Hockert O, Poisson N, et al. Second IUATLD study on complications induced by intradermal BCG-vaccination. Bull Int Union Tuberc Lung Dis. 1988;63:47–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clements CJ, ed. Supplementary Information on Vaccine Safety: Part 2: Background and Rates of Adverse Events Following Immunization. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Vaccines and Biologicals, World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuello-Garcia CA, Perez-Gaxiola G, Jimenez Gutierrez C. Treating BCG-induced disease in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(1):CD008300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kroger L, Korppi M, Brander E, et al. Osteitis caused by bacille Calmette-Guerin vaccination: a retrospective analysis of 222 cases. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:574–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]