Abstract

We report a 15-year-old female with POLG-related mitochondrial disease who developed severe multifocal epilepsia partialis continua, unresponsive to standard anti seizure drug treatment and general anesthesia. Based on an earlier case report, we treated her focal seizures that affected her right upper limb with 20-min sessions of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) at an intensity of 2 mA on each of five consecutive days. The cathode was placed over the left primary motor cortex, the anode over the contralateral orbitofrontal cortex. Surface electromyography (EMG) were recorded 20 min before, 20 min during, and 20 min after four of five tDCS sessions to measure its effect on the muscle jerks. The electroencephalography (EEG) was recorded before and after tDCS to measure the frequency of spikes. Our results showed no statistically or clinically significant reduction of seizures or epileptiform activity using EEG and EMG, with this treatment protocol. To our knowledge, this is only the second time that adjunct tDCS treatment of epileptic seizures has been tried in POLG-related mitochondrial disease. Taken together with the positive findings from the earlier case report, the present study highlights that more data are needed to determine if, and under which parameters, the treatment is effective.

Keywords: Mitochondrial disease, POLG, Neurostimulation, tDCS, Refractory status epilepticus

Highlights

-

•

Case report of multifocal epilepsy in POLG disease with upper limp myoclonus.

-

•

Epileptic activity resulting in myoclonus was treated with 5 days of 20 minutes cathodal 2 mA tDCS over left motor cortex.

-

•

tDCS treatment did not yield significant reduction of myoclonus activity.

1. Introduction

Mitochondrial diseases are a group of genetic disorders affecting about one in 5000 people [1]. The symptoms are diverse but since mitochondria produce energy for body tissues through production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), organs with high energy consumption, such as the brain, are often affected. For example, as many as 35% to 60% of people with mitochondrial disease develop seizures [1]. In POLG-related mitochondrial disease, a genetic mutation interferes with a catalytic subunit of the mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma, which replicates mitochondrial DNA [2], leading to depleted mitochondrial DNA [3]. Once the resulting neuronal energy failure reaches a critical point, neuronal death ensues, causes atrophy and potentially acts as the trigger for epilepsy that in turn increases neuronal loss [4]. A study found mitochondrial dysfunction in one third of patients with epilepsy that underwent metabolic testing [5], emphasizing that drug-resistant seizures are a frequent problem in mitochondrial disease, and that new treatments need to be developed. In a previous case report, focal seizures in a patient with POLG-related mitochondrial disease ceased after two weeks of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) [6]. Since these seizures are often refractory to medical treatment and the technique is non-invasive, we tested tDCS using similar parameters as in Ng et al. [6] in a patient with POLG-related mitochondrial disease and drug-resistant multifocal epilepsy.

1.1. Case report

This 15-year-old female was apparently healthy until the first admission followed two consecutive generalized tonic–clonic seizures. Prior to the seizures, she had experienced nausea, headache, reduced vision and paraesthesia in both upper limbs. She was intubated during helicopter transfer to hospital due to reduced consciousness. Following admission, she regained consciousness, but developed continuous jerking of her right arm. EEG showed ongoing epileptiform discharges over the right occipital region (Fig. 1A) that later involved most of the right cerebral hemisphere, and because of persisting uncontrolled epileptic activity she was loaded with phosphenytoin before using anesthesia with propofol and ketamine at relevant clinical dosages to provide effective serum levels, as well as lowering her core body temperature to 33 °C in accordance with the Norwegian treatment guidelines [7]. The clinical presentation with status epilepticus involving an occipital lobe focus prompted investigation for POLG mutation, which was subsequently confirmed through DNA sequencing analysis showing a homozygous genotype c.2243G > C.

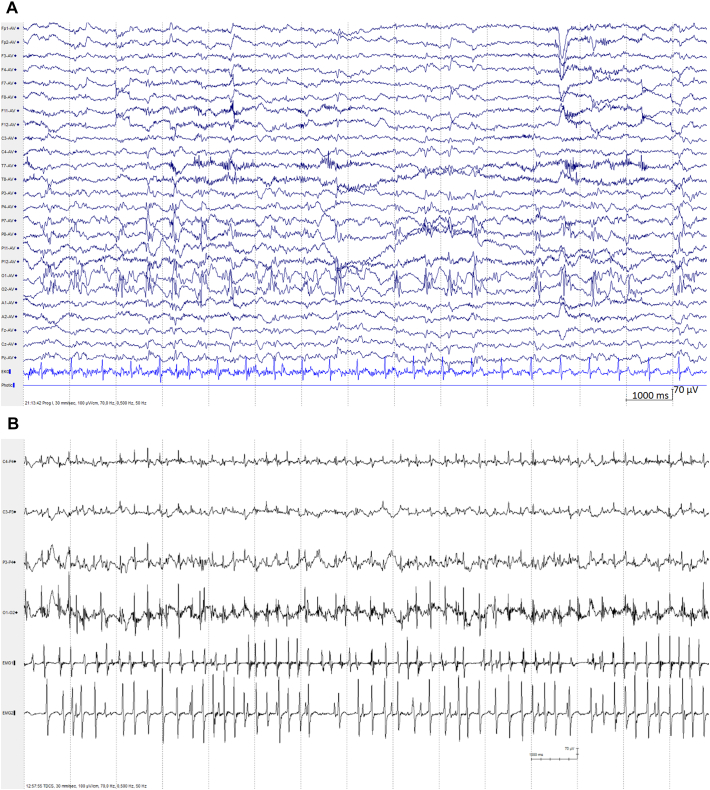

Fig. 1.

POLG disease visualized through EEG examples. Panel A) EEG sample from the patient from an early clinical recording, showing almost continuous 2 Hz polyspike-and-slow waves mainly over the right parieto-occipital region. Panel B) Continuous EEG recording from the tDCS experiment showing channels (from top to bottom) C4, C3, P3, O1 and EMG1 and EMG2 being the right hand and left trapezius, respectively.

Following two episodes of propofol anesthesia and achieving burst suppression, she regained consciousness and her epilepsy was then treated with phenobarbital and oxcarbazepine while withdrawing phenytoin. After stabilization, the patient was discharged with ongoing medication treatment. She was readmitted a second and third time with headache and visual disturbances that quickly morphed into generalized tonic–clonic seizures, followed by focal motor status epilepticus, both episodes treated with anesthesia and hypothermia. On the third occasion, her MRI showed new changes in both occipital regions. During the second prolonged admission, she still had jerking of her right arm despite maintaining phenytoin, levetiracetam, oxcarbazepine, topiramate and clobazam at therapeutic doses. At the point where tDCS treatment was instituted, the patient had a multifocal seizures with multiple semiologies (Fig. 1A and B) including a multifocal, asynchronous myoclonus, that was dominant and most debilitating in the right hand. We thus targeted the left primary motor cortex with tDCS, as the myoclonus activity most likely arose from that area, with the goal to relieve pain and disability.

1.2. Methods of tDCS and EEG

The use of tDCS was discussed with the local ethical committee who considered it a form of supplementary experimental treatment whose purpose was to provide care for an individual, and for which the caring physician could take responsibility without obtaining the committees' approval. Verbal consent was obtained from the parents and treatment was reported in the patient's medical journal. tDCS was applied for 20 min at 2 mA on each of five consecutive days with a DC-Stimulator PLUS (neuroConn, Ilmenau, Germany) through 5 × 7 cm rubber electrodes with saline soaked sponges giving a current density of 0.057 mA/cm2. The patient displayed continuous jerking in the right hand muscles and left shoulder muscles. To reduce the jerking of the right hand, the cathode was placed over the contralateral left primary motor cortex at approximately C3 of the 10–20 EEG system (see Fig. 2A). The rationale was that cathodal stimulation has been shown to reduce cortical excitability in the brain area underneath the electrode and hence might reduce epileptic activity causing the myoclonus [8]. The anode was placed on the right orbitofrontal cortex (approximately Fp2). By placing the electrode on the contralateral side, the electric field between anode and cathode crosses the midline and was hoped to affect the motor cortex most effectively. Since the anode is active and expected to increase cortical excitability, a better setup would have included an extra-large anode that would effectively reduce the current strength. However, as the tDCS treatment was issued at short notice, we did not have large electrodes available at the time. We chose the orbitofrontal region, because it is often used as a control site in tDCS experiments [9] and because it was not particularly affected by epilepsy. Indeed, we did not observe a worsening in the EEG in this region after the treatment. The tDCS setup was used in accordance with safety guidelines [10,11].

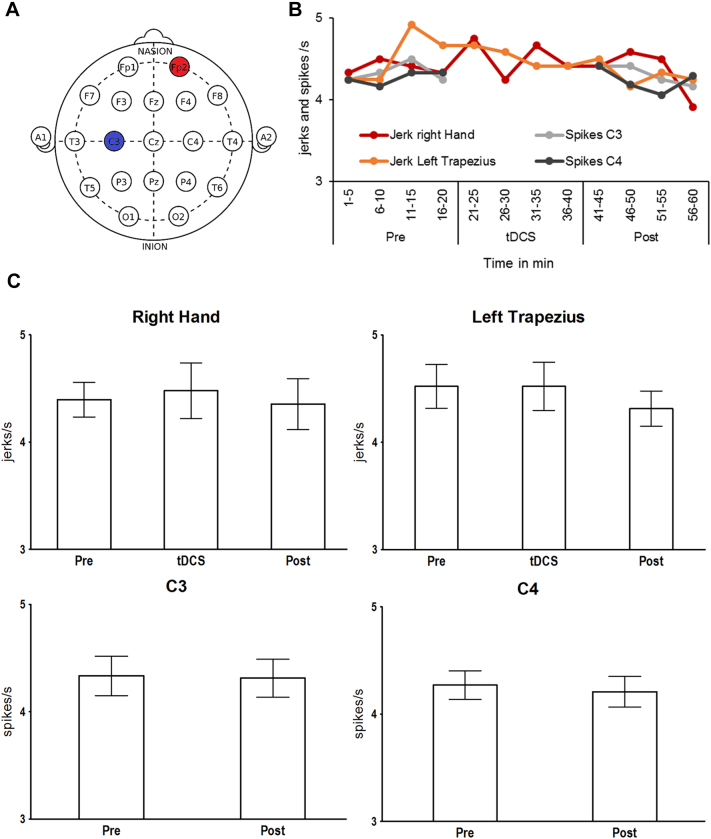

Fig. 2.

tDCS montage and results. Panel A) Placement of anode at Fp2 (red) and cathode at C3 (blue) within the international 10/20 system. Panel B) Means of spikes/jerks per second across all four days. Time in minutes. Panel C) Spikes/jerks per second and 95% confidence intervals before, during, and after treatment.

Initial EEG recordings and seizure monitoring during status epilepticus were done with continuous 25 channel clinical EEG and scored visually by experienced neurophysiologists. With the cathode placed over the left primary motor cortex, we looked for improvement particularly in the right hand. Continuous EEG was measured from C3 and C4 (right motor cortex as control) for 20 min before and 20 min after tDCS, from a clinical EEG setup following the 10/20 system with 6 + 2 (F3, F4, P3, P4, O1, O2) electrodes and video monitoring of the patient. EMG data from the right hand and left trapezius was acquired continuously for 20 min before tDCS, during 20 min tDCS, and 20 min after tDCS. EEG data was not interpretable during tDCS due to amplifier blocking. EMG and EEG data were recorded on four out of five days.

Three separate raters, two neurophysiologists (TE, HKO) and the tDCS clinician (LM), counted the frequency of spikes (EEG) and muscle jerks (EMG) drawn from multiple random samples. Specifically, the data were binned into 12 five-minute segments. Then, each rater picked randomly ten, artifact-free one-second periods from each five-minute segment on all four days and determined the mean number of EEG spikes and EMG jerks per second (Hz) for all four measurements (C3, C4, right hand, left trapezius). Subsequently, means were calculated across raters (see Fig. 2B) and EEG data was subjected to paired sample t-tests and non-parametric Wilcoxon tests, comparing spikes before and after tDCS. The means for EMG data were subjected to an ANOVA with the repeated measures variable Time (before, during after tDCS) and a non-parametric Friedman test. Non-parametric Friedman and Wilcoxon tests were included because not all variables met the normal distribution criterion necessary for t-tests and ANOVAs — due to the limited range of values for spikes/jerks per second. At the same time, non-parametric tests are sometimes not sensitive enough to pick up small effects. In the interest of comprehensiveness, we thus decided to report findings from both ANOVA/Friedman and paired sample t-tests/Wilcoxon tests. We also compared the pre-tDCS data on day one (baseline) to the post-tDCS data on day five using t- and Wilcoxon tests, assuming that the treatment effect should be strongest between these measurement points.

2. Results

Fig. 2C shows the average frequency of epileptic spikes and jerks in the right hand and left shoulder during treatment. According to t-tests/Wilcoxon tests for EEG data and the ANOVAs/Friedman tests for EMG data, there were no significant differences in the means across all raters in C3 or C4 spikes (all ts(15) ≤ 0.613, all ps ≥ 0.549; all χ2s(1) ≤ 0.091, all ps ≥ 0.763) as well as jerks in the right hand and left shoulder (all Fs(2,30) ≤ 1.74, all ps ≥ 0.192; all Zs ≥ 0.642, all ps ≥ 0.521). The mean spikes and jerks across all raters for pre-tDCS on day one (baseline) versus post-tDCS on day five were for the right hand 4.58 ± 0.32 and 4.42 ± 0.57, left trapezius 4.58 ± 0.32 and 4.08 ± 0.42 jerks/s, C3 4.50 ± 0.43 and 4.25 ± 0.32 and C4 4.25 ± 0.32 and 4.13 ± 0.17 spikes/s, respectively. None of these changes were significant (all ts ≤ 1.57, all ps ≥ 0.215; all Zs ≤ 1.34, all ps ≥ 0.180).

TDCS treatment was given in March 2018. The stimulation itself was well tolerated. The patient only reported short-term skin irritation from the net holding the electrodes in place. Four months after receiving tDCS, the patient was discharged from the hospital, still with upper limb jerking, but was readmitted in December 2018 and died due to a super-refractory status epilepticus.

3. Discussion

Neither spike nor jerk frequency changed over the course of five tDCS sessions (between before, during, and after tDCS) or when comparing baseline spike/jerk rates from day one to after treatment on day five. We therefore conclude that – in this case study – tDCS did not have a beneficial treatment effect on treatment-resistant refractory epilepsia partialis continua in POLG-related mitochondrial disease. Hence, our results are inconsistent with those of Ng et al. [6], who found that seizures stopped completely in a similar case study.

There are several differences between the two case studies that could explain the different outcomes: Ng et al. [6] placed the cathode over the right temporo-parietal–occipital junction (P4/T6), while in our study it was over the left primary motor cortex. Ng et al. provided tDCS treatment twice, once for three days and once for 14 days, while we provided tDCS treatment once for five days. However, the treatment in our case was stopped before the completion of 14 days because there was no sign of improvement and due to technical reasons/staff availability. Moreover, while the patients appeared to have similar seizure frequency their genotypes were different; the patient reported by Ng and colleagues was homozygous for the c.1399G > A whereas our patient was homozygous for the c.2243G > C genotype. Both patients were also on multiple, but different anticonvulsant regimens, raising the possibility that competing mechanisms modulated response to tDCS. Lastly, our case was severe, so by the time we started the intervention the seizures may have become refractory to both medication and tDCS treatment. We cannot rule out that cathodal stimulation elsewhere (e.g., over the right occipital region) might have yielded a better treatment response, perhaps, at an earlier stage of the disease. However, while the patient had a multifocal epilepsy with multiple semiologies, we specifically targeted the left motor cortex to reduce the myoclonic jerking of the right hand that the patient found very debilitating. Similarly, we cannot rule out that stimulating for more than five days would have worked better.

According to guidelines published by a European expert consortium in 2017, and several reviews, it is not yet possible to draw conclusions regarding the efficacy of tDCS in any kind of epilepsy, even though there are some promising results [[12], [13], [14], [15]]. Similarly, it remains unclear whether transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS), another type of non-invasive brain stimulation, is an effective treatment of epilepsy [[16], [17], [18]], although there are some positive findings for epilepsia partialis continua [19]. Even less is known about how these non-invasive brain stimulation techniques will affect patients with mitochondrial diseases. However, given that refractory epilepsy appears to be common in these diseases [5], finding novel treatments is highly relevant. To our knowledge, this is only the second documented attempt to use tDCS in mitochondrial disease. With one positive and one negative result, it is too early to say whether tDCS will find a place in the treatment of mitochondrial epilepsy, but during the early stages of any new treatment, all findings, negative or positive, need to be published to obtain a clearer overall picture. This is particularly relevant in this case, where almost nothing is known about the efficacy of tDCS for epilepsy in patients with mitochondrial diseases. Further, because the condition is so rare, it is difficult to realize randomized controlled trials with decent sample sizes and that could control for potential placebo effects. A final reason for why we deem it important to report this negative finding is – despite its limited contribution to the literature – that there is growing awareness of reporting bias and replication issues in the scientific community and with it a growing recognition of the relevance of negative findings. We hope that our findings contribute to a growing body of literature and encourage other scientists to provide larger samples and proper clinical trials.

Author contribution

Conception and design of the study: LAB, GV and MH. Acquisition of data: LM, IK, TE, HKO, MH and LAB. Analysis and interpretation of data: LM, IK, TE, HKO and MH. Drafting the manuscript or figures: All authors. Critical review and revision: All authors.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We express our deepest gratitude to the patient and would like to give our heartfelt condolences to the bereaved family. The present research was funded by a grant from the Bergen Research Foundation (BFS2016REK03) to Marco Hirnstein and the Haukeland University Hospital.

Ethical statement

The work described has been carried out in accordance with the Code of Ethics of the World Medical Association (Declaration of Helsinki). We confirm that we have read the journal's position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Contributor Information

Lynn Marquardt, Email: lynn.marquardt@uib.no.

Tom Eichele, Email: tom.eichele@helse-bergen.no.

Laurence A. Bindoff, Email: laurence.albert.bindoff@helse-bergen.no.

Henning Kristian Olberg, Email: henning.kristian.olberg@helse-bergen.no.

Gyri Veiby, Email: gyri.veiby@helse-bergen.no.

Heike Eichele, Email: heike.eichele@uib.no.

Isabella Kusztrits, Email: isabella.kusztrits@uib.no.

Marco Hirnstein, Email: marco.hirnstein@uib.no.

References

- 1.Rahman S. Mitochondrial disease and epilepsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2012;54:397–406. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2011.04214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bindoff L.A., Engelsen B.A. Mitochondrial diseases and epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2012;53:92–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2012.03618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tzoulis C., Tran G.T., Coxhead J., Bertelsen B., Lilleng P.K., Balafkan N. Molecular pathogenesis of polymerase gamma-related neurodegeneration. Ann Neurol. 2014;76:66–81. doi: 10.1002/ana.24185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hikmat O., Eichele T., Tzoulis C., Bindoff L.A. Understanding the epilepsy in POLG related disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1845. doi: 10.3390/ijms18091845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikh S., Cohen B.H., Gupta A., Lachhwani D.K., Wyllie E., Kotagal P. Metabolic testing in the pediatric epilepsy unit. Pediatr Neurol. 2008;38:191–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng Y.S., van Ruiten H., Lai H.M., Scott R., Ramesh V., Horridge K. The adjunctive application of transcranial direct current stimulation in the management of de novo refractory epilepsia partialis continua in adolescent-onset POLG-related mitochondrial disease. Epilepsia open. 2018;3:103–108. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torgrimsen E., Stensland B., Ljøstad U., Mygland Å. In. 22.09.2017 ed. helsebiblioteket.no: Folkehelseinstituttet. 2017. Epilepsi – anfallsklassifisering og akuttbehandling til pasienter med epileptiske anfall; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nitsche M.A., Paulus W. Excitability changes induced in the human motor cortex by weak transcranial direct current stimulation. J Physiol. 2000;527:633–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2000.t01-1-00633.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horvath J.C., Forte J.D., Carter O. Quantitative review finds no evidence of cognitive effects in healthy populations from single-session transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) Brain Stimul. 2015;8:535–550. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.01.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stagg C.J., Nitsche M.A. Physiological basis of transcranial direct current stimulation. Neuroscientist. 2011;17:37–53. doi: 10.1177/1073858410386614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bikson M., Grossman P., Thomas C., Zannou A.L., Jiang J., Adnan T. Safety of transcranial direct current stimulation: evidence based update 2016. Brain Stimul. 2016;9:641–661. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.San-juan D., Morales-Quezada L., Garduño A.J.O., Alonso-Vanegas M., González-Aragón M.F., López D.A.E. Transcranial direct current stimulation in epilepsy. Brain Stimul. 2015;8:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.brs.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin Y., Wang Y. Neurostimulation as a promising epilepsy therapy. Epilepsia open. 2017;2:371–387. doi: 10.1002/epi4.12070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lefaucheur J.-P., Antal A., Ayache S.S., Benninger D.H., Brunelin J., Cogiamanian F. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128:56–92. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2016.10.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.San-Juan D., Sarmiento C.I., González K.M., Barraza O., Manuel J. Successful treatment of a drug-resistant epilepsy by long-term transcranial direct current stimulation: a case report. Front Neurol. 2018;9:65. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen R., Spencer D.C., Weston J., Nolan S.J. Transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(8) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011025.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefaucheur J.-P., André-Obadia N., Antal A., Ayache S.S., Baeken C., Benninger D.H. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) Clin Neurophysiol. 2014;125:2150–2206. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2014.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fisher R., Zhou J., Fogarty A., Joshi A., Markert M., Deutsch G.K. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation directed to a seizure focus localized by high-density EEG: a case report. Epilepsy Beh Case Rep. 2018;10:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ebcr.2018.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rotenberg A., Bae E.H., Takeoka M., Tormos J.M., Schachter S.C., Pascual-Leone A. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of epilepsia partialis continua. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:253–257. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]