Abstract

Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD) is a central nervous system (CNS) demyelinating disease in human, currently known as prototypic hypomyelinating leukodystrophy 1 (HLD1). The gene responsible for HLD1 encodes proteolipid protein 1 (PLP1), which is the major myelin protein produced by oligodendrocytes. HLD9 is an autosomal recessive disorder responsible for the gene differing from the plp1 gene. The hld9 gene encodes arginyl-tRNA synthetase (RARS), which belongs to a family of cytoplasmic aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. Herein we show that HLD9-associated missense mutation of Ser456-to-Leu (S456L) localizes RARS proteins as aggregates into the lysosome but not into the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the Golgi body. In contrast, wild-type proteins indeed distribute throughout the cytoplasm. Expression of S456L mutant constructs in cells decreases lysosome-related signaling through ribosomal S6 protein phosphorylation, which is known to be required for myelin formation. Cells harboring the S456L mutant constructs fail to exhibit phenotypes with myelin web-like structures following differentiation in FBD-102b cells, as part of the mammalian oligodendroglial cell model, whereas parental cells exhibit them. Collectively, HLD9-associated RARS mutant proteins are specifically localized in the lysosome with downregulation of S6 phosphorylation involved in myelin formation, inhibiting differentiation in FBD-102b cells. These results present some of the molecular and cellular pathological mechanisms for defect in myelin formation underlying HLD9.

Keywords: Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy, Arginyl-tRNA synthetase, Lysosome, Oligodendrocyte, Differentiation

Highlights

-

•

RARS proteins are localized throughout the cytoplasm.

-

•

HLD9-associated RARS mutant proteins are localized in the lysosome.

-

•

RARS mutant proteins form aggregates in polyacrylamide electrophoresis.

-

•

Cells harboring RARS mutant constructs inhibit oligodendroglial differentiation.

1. Introduction

Myelin sheaths are derived from the differentiated plasma membranes of myelin-forming glial cells, which are called oligodendroglial cells (oligodendrocytes) in the central nervous system (CNS) and Schwann cells in the peripheral nervous system (PNS). They often grow to more than 100 times larger than the collective surface area of the premyelinating plasma membranes of oligodendrocytes or Schwann cells [1,2]. Myelin sheaths play an indispensable role in the propagation of saltatory conduction and in protecting neuronal axons from physical and physiological stresses [3,4]. Hypomyelinating leukodystrophies (HLDs) are a group of genetic neuropathies in the CNS. Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease (PMD) is the prototypic HLD, and is now designated as HLD1 [[5], [6], [7], [8]]. HLDs are due to a defect in myelin formation. HLDs are thus considered severe neuropathies [[5], [6], [7], [8]].

HLD1 is responsible for the plp1 gene whose gene product is the major myelin membrane protein [5,6]. The gene responsible for HLD2 encodes the GJC2 gap junction protein [9]. Recent advancements in nucleotide sequencing have enabled the identification of unexpected types of HLD-responsible genes. The gene responsible for HLD9 encodes arginyl-tRNA synthetase (RARS) (OMIN ID 616140). RARS belongs to the aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase family of proteins [10,11]. It ligates arginine to the cognate tRNA whose backbone sequence contains anticodon for arginine. It was recently reported that the Ser456-to-Leu (S456L) mutation in the catalytic domain of human RARS is associated with HLD9 [12,13]; however, it remains to be investigated whether the S456L mutation of RARS has biochemical and cell biological effects and, if so, what they are. Herein, we for the first time report that the S456L mutant proteins of cytoplasmic RARS are specifically localized in the lysosome with decreased lysosome-related ribosomal S6 protein phosphorylating signaling, thereby inhibiting morphological differentiation in mouse oligodendrocyte cell line FBD-102b cells. These results provide some of molecular and cellular pathological mechanisms for defect in myelin formation underlying HLD9-associated RARS mutation.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Primary antibodies

The following antibodies were purchased: mouse monoclonal anti-endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-resident Grp78 antigen's KDEL peptide (Cat. No. M181-3; immunofluorescence [IF], 1/200) and mouse monoclonal anti-GFP (Cat. No. M048-3; immunoblotting [IB], 1/1000) from MBL (Aichi, Japan); mouse monoclonal anti-lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) (Cat. No. ab25630; IF, 1/100) and mouse monoclonal anti-(pSer240/244) ribosomal S6 protein (Cat. No. ab215214; IF, 1/100) from Abcam (Bristol, UK); and mouse monoclonal anti-Golgi matrix protein of 130 kDa (GM130) (Cat. No. 610822; IF, 1/200) from BD Biosciences (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

2.2. Plasmid constructions

Human RARS (GenBank Acc. No. NM_002887) was amplified by the RT-PCR method using human fetal brain total RNA (Toyobo Life Science, Osaka, Japan) and ligated into the green fluorescence protein (GFP)-expressing pEGFP-N3 vector (Takara Bio, Shiga, Japan). S456L mutation (OMIN ID 616140 was produced from pEGFP-N3-human RARS as the template, using a site-directed mutagenesis kit (Toyobo Life Science) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. All DNA sequences were confirmed by sequencing (Fasmac, Kanagawa, Japan).

2.3. Cell culture, differentiation, transfection, and isolation of stable clones

African green monkey kidney epithelial cell-like COS-7 cells were cultured on cell culture dishes (Greiner, Oberösterreich, Germany) in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS and PenStrep (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. COS-7 cells were kindly provided by Dr. T. Sakurai (Tsukuba University, Ibaragi, Japan).

Mouse brain oligodendroglial FBD-102b cells were cultured on cell culture dishes in DMEM/Nutrient Mixture F-12 (F-12) containing 10% heat-inactivated FBS and PenStrep in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. To induce differentiation, FBD-102b cells were cultured on cell culture dishes with advanced TC polymer modification in culture medium without FBS in 5% CO2 at 37 °C. Cells with myelin web-like membrane structures along multiple processes from cell bodies were considered to be differentiated ones [14,15]. FBD-102b cells were kindly provided by Dr. Y. Tomo-oka (Tokyo University of Science, Chiba, Japan).

Cells were transfected with the respective plasmids using a ScreenFect A or ScreenFect A Plus transfection kit (Wako) in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The medium was replaced 4 h after transfection and was generally used for experiments 48 h after transfection.

For collection of FBD-102b cells stably harboring the S456L mutant constructs of RARS, cells were transfected with pEGFP-N3-RARS (S456L) in a 3.5 cm cell culture dish. Growth medium containing 2500 μg/ml G418 (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) was changed every 2 or 3 days. After more than 14 days, G418-resistant colonies were collected and compared with the phenotypes of their parental cells.

2.4. Fluorescence images

Cells on a coverslip were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde or 100% cold methanol. Cells were blocked with Blocking One reagent (Nacalai Tesque) and incubated first with primary antibodies and then with Alexa Fluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific or Abcam) [16]. The coverslips on the slide glass were mounted with Vectashield reagent (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). The TIFF images were collected with a microscope system equipped with a laser-scanning Fluoview apparatus (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) using Fluoview software (Olympus). The resulting colored images were analyzed in both Image J software (URL: https://imagej.nih.gov/) for line plots and UN-SCAN-IT software (URL: https://www.silkscientific.com/gel-analysis.htm) for pixel captures. Images in figures are representative of three experimental results.

2.5. Polyacrylamide electrophoresis and immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM phenylmethane sulfonylfluoride, 1 μg/ml leupeptin, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 10 mM NaF, and 0.5% NP-40) and were prepared as described [17,18]. For non-denatured conditions, the supernatants were denatured with non-denaturing sample buffer (Nacalai Tesque). The samples were separated on premade non-denatured (native) polyacrylamide gels (Nacalai Tesque). The proteins separated electrophoretically were transferred to a PVDF membrane, blocked with Blocking One reagent, and immunoblotted using primary antibodies, followed by peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (Nacalai Tesque or MBL). The bound antibodies were detected by X-ray film exposure using ImmunoStar Zeta reagent (Wako). The films were captured as TIFF image files using a GT-X770 scanner (Epson, Nagano, Japan) and its driver software (Epson). The band pixels were measured in the segment analysis mode using UN-SCAN-IT software. The pixel values of protein bands were described as percentages and were compared with the control values. Images in figures are representative of three experimental results.

2.6. Ethics statement

Gene recombination techniques were performed in accordance with a protocol approved by both the Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences Gene and Animal Care Committee and the Japanese National Research Institute for Child Health and Development Gene and Animal Care Committee.

3. Results

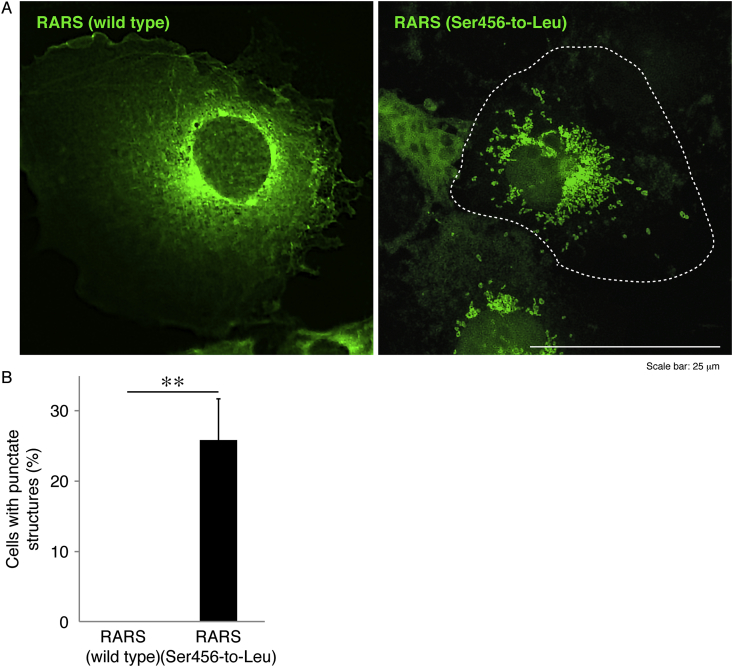

In order to examine whether HLD9-associated S456L mutant proteins of GFP-tagged RARS are localized in the cytoplasm or other organelles, we transfected the plasmid encoding wild-type or mutant RARS into COS-7 cells. Since epithelial-like COS-7 cells have wide cytoplasmic regions, they are useful for observing the localization of proteins in organelles. The wild-type RARS proteins were indeed localized in the cytoplasm, which is consistent with previous results [10,11]. In contrast, mutant proteins formed punctate structures by 25% (Fig. 1A and B).

Fig. 1.

Ser456-to-Leu mutant proteins exhibit punctate structures whereas wild-type proteins exhibit cytoplasmic localization. (A) COS-7 cells were transfected with the plasmid encoding wild-type or mutant RARS with a GFP-tag and were obtained as fluorescence images (green). The dotted outline indicates the periphery of the cell. (B) Percentages of cells with punctate structures are statistically shown (**, p < 0.01 in the Student's t-test; n = 3 fields).

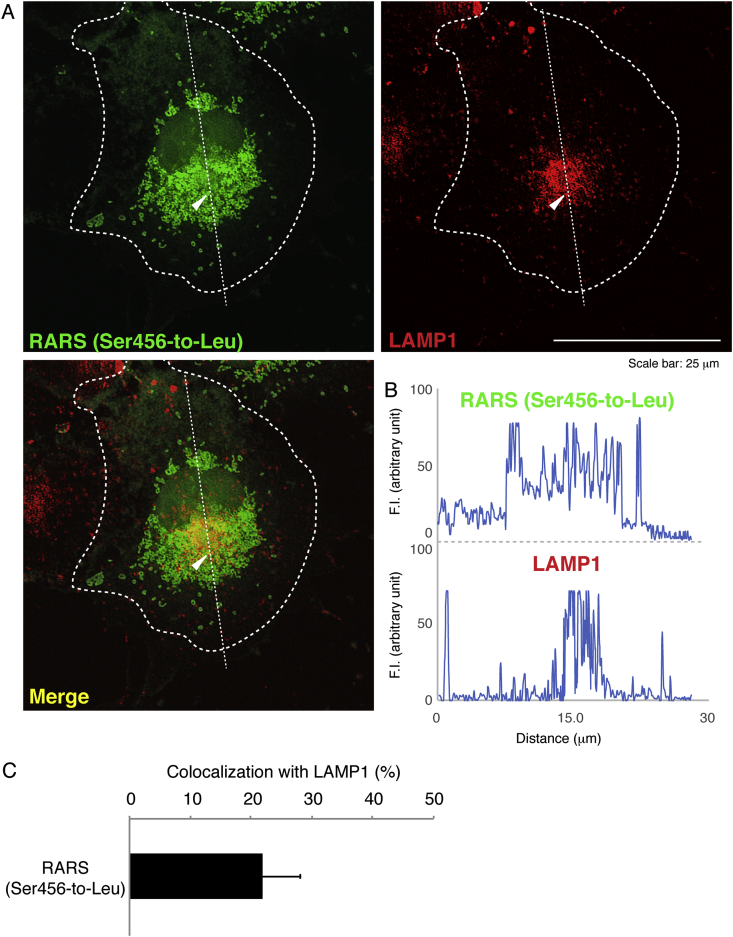

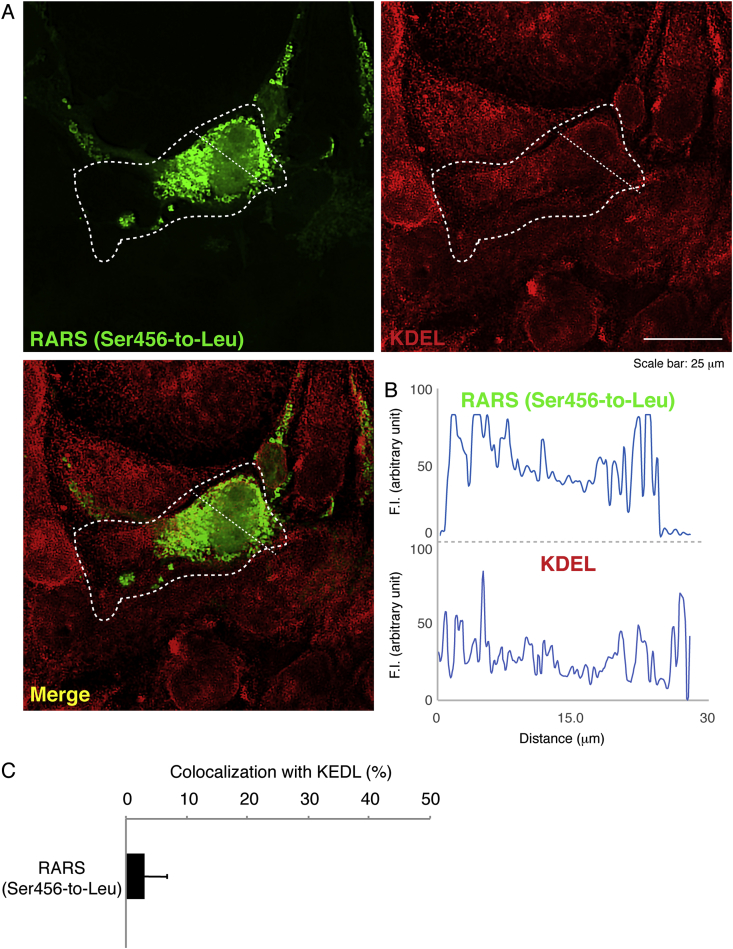

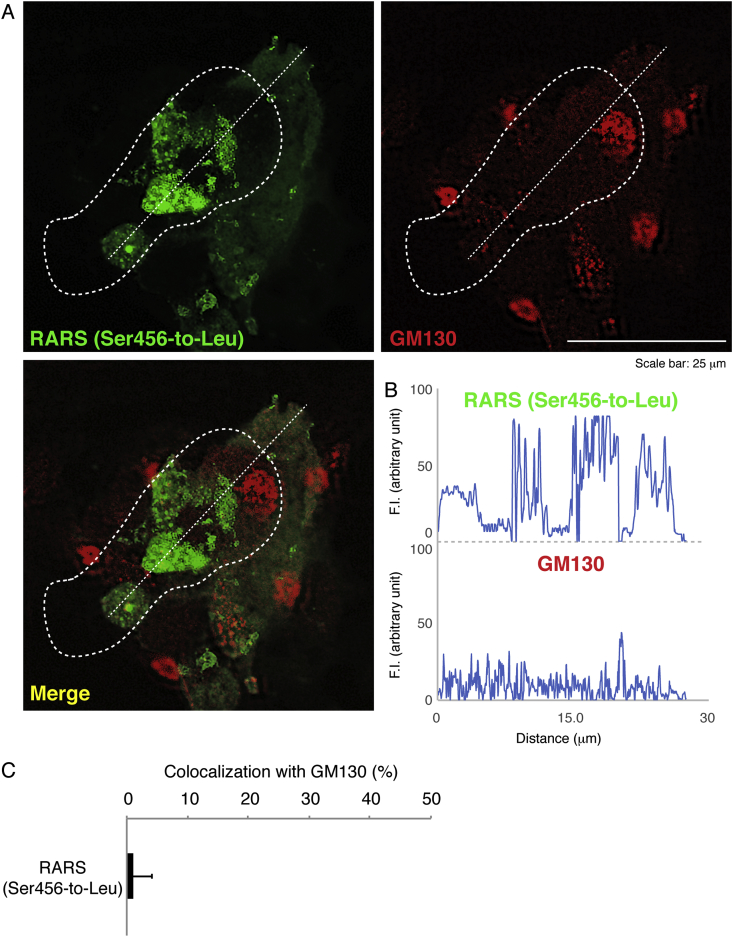

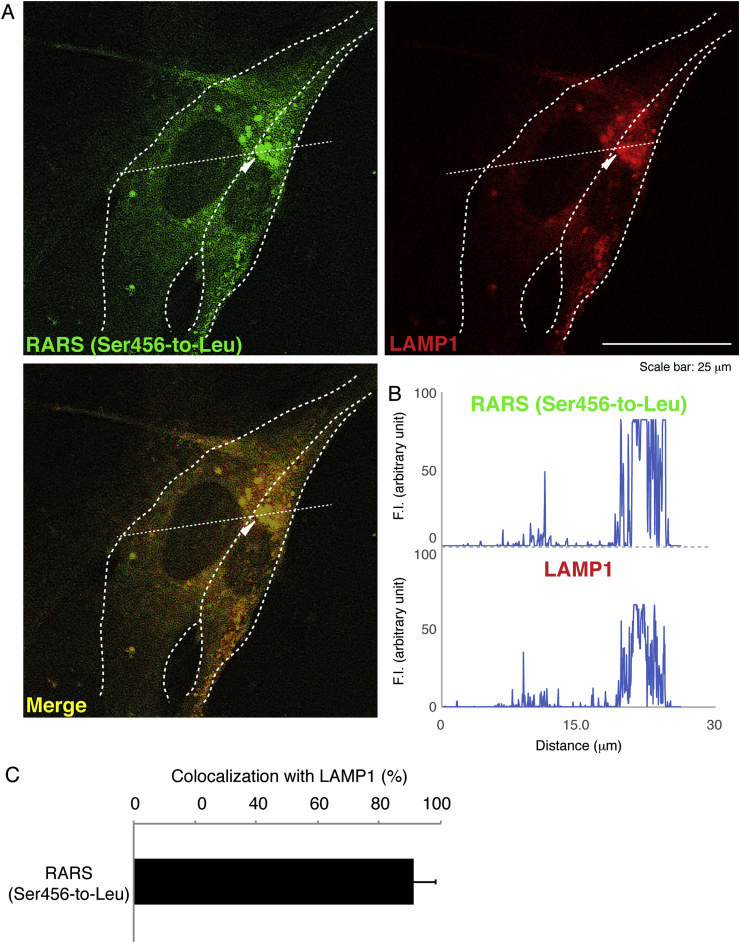

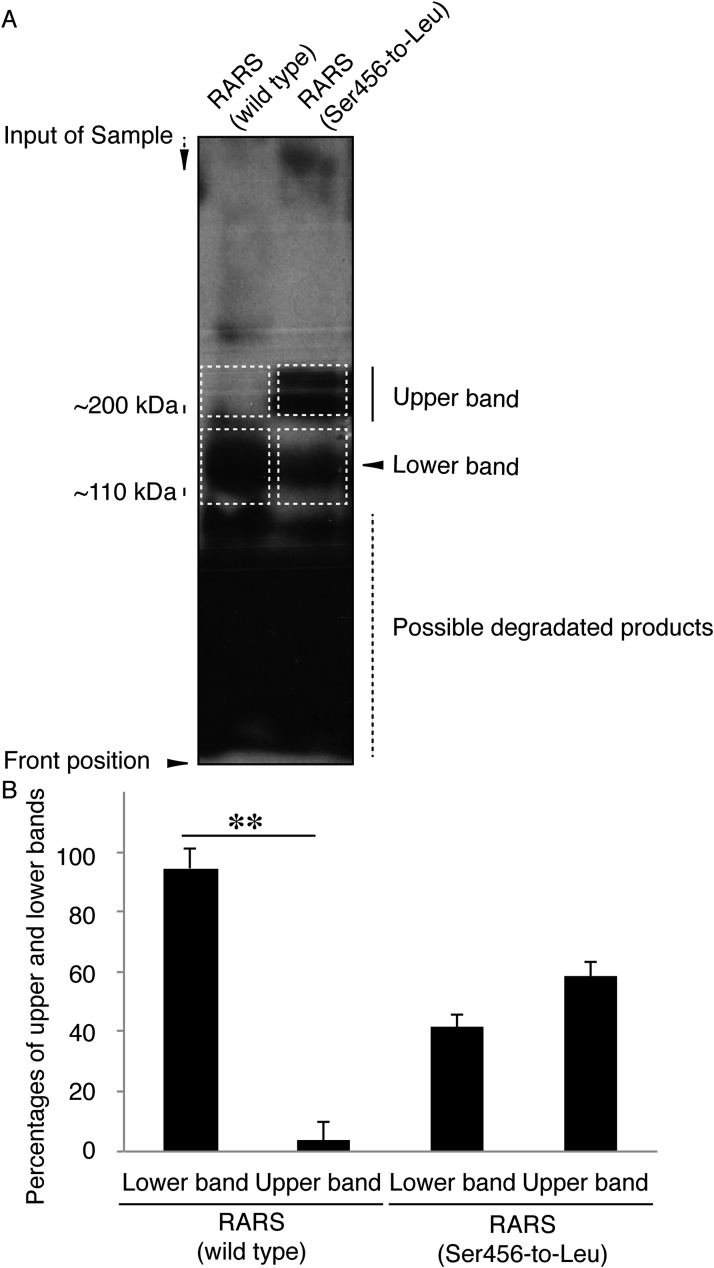

Next, we investigated which organelle contains mutant proteins. We stained cells transfected with the plasmid encoding the mutant RARS with the respective antibodies for the ER (a KDEL antigen), the Golgi body (a GM130 antigen), or the lysosome (a LAMP1 antigen). Mutant RARS proteins were co-localized with LAMP1 antigens by approximately 25% (Fig. 2A–C) whereas they were not with neither KDEL antigens (Fig. 3A–C) nor GM130 antigens (Fig. 4A–C). Similar localization of mutant RARS proteins in the lysosome was observed in oligodendroglial FBD-102b cells (Fig. 5A–C). In polyacrylamide electrophoresis in non-denatured conditions, mutant RARS proteins, but not the wild-type ones, primarily corresponded to a mobilizing position of possible dimeric aggregates (Fig. 6A and B).

Fig. 2.

Ser456-to-Leu mutant proteins are localized in the lysosome. (A) COS-7 cells were transfected with the plasmid encoding the mutant (green) and were immunostained with an anti-LAMP1 antibody (red). The merged image (yellow) is also shown. Dotted outlines indicate the periphery of the cell. Arrowheads indicate a typical aggregate. (B) Fluorescence intensities (F.I., arbitrary unit) of green and red along the dotted lines (up-to-down direction) in the upper left and right images of panel A are shown, respectively. (C) Percentages of merged yellow pixels per mutant green ones are statistically shown (n = 3 fields).

Fig. 3.

Ser456-to-Leu mutant proteins are minimally localized in the ER. (A) COS-7 cells were transfected with the plasmid encoding the mutant (green) and were immunostained with an anti-KDEL antibody (red). The merged image (yellow) is also shown. Dotted outlines indicate the periphery of the cell. (B) Fluorescence intensities (F.I., arbitrary unit) of green and red along the dotted lines (left upper-to-right down direction) in the upper left and right images of panel A are shown, respectively. (C) Percentages of merged yellow pixels per mutant green ones are statistically shown (n = 3 fields).

Fig. 4.

Ser456-to-Leu mutant proteins are hardly localized in the Golgi. (A) COS-7 cells were transfected with the plasmid encoding the mutant (green) and were immunostained with an anti-GM130 antibody (red). The merged image (yellow) is also shown. Dotted outlines indicate the periphery of the cell. (B) Fluorescence intensities (F.I., arbitrary unit) of green and red along the dotted lines (left down-to-right upper direction) in the upper left and right images of panel A are shown, respectively. (C) Percentages of merged yellow pixels per mutant green ones are statistically shown (n = 3 fields).

Fig. 5.

Ser456-to-Leu mutant proteins are localized in the lysosome in an oligodendroglial cell line. (A) FBD-102b cells were transfected with the plasmid encoding the mutant (green) and were immunostained with an anti-LAMP1 antibody (red). The merged image (yellow) is also shown. Dotted outlines indicate the periphery of the cell. (B) Fluorescence intensities (F.I., arbitrary unit) of green and red along the dotted lines (left-to-right direction) in the left and right images of panel A are shown, respectively. (C) Percentages of merged yellow pixels per mutant green ones are statistically shown (n = 3 fields).

Fig. 6.

Ser456-to-Leu mutant proteins prefer to form dimeric structures in polyacrylamide electrophoresis. (A) The plasmid encoding the wild type or mutant of GFP-tagged RARS were transfected into COS-7 cells, subjected to non-denaturing polyacrylamide electrophoresis, and detected by immunoblotting with an anti-GFP antibody. The predicted molecular mass of GFP-tagged wild-type RARS is approximately 110 k and is indicated as a monomer position (lower dotted squares). GFP-tagged mutant proteins exhibit two forms with positions of approximately 110 kDa and 200 kDa markers. 200 kDa proteins correspond to the position (dotted squares) of RARS dimer. (B) Percentages of lower or upper band intensities per total band intensities are statistically shown (**, p < 0.01 of one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA] followed by a Fisher's protected least significant difference test as a post hoc comparison; n = 3 blots).

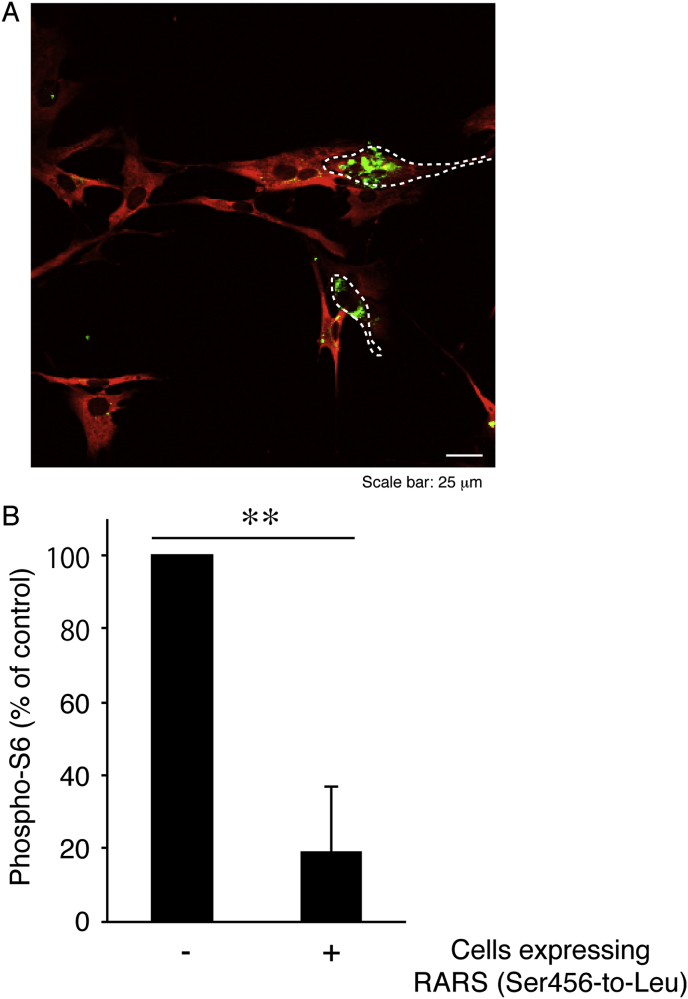

Since mammalian targets of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling molecules are involved in a large functional complex on the lysosomal membrane [19,20], we examined whether mutant RARS proteins affect the activities of mTOR signaling in FBD-102b cells. The major outputs of mTOR signaling are phosphorylation of proteins such as ribosomal S6 or 4E-BP1 [19,20]. In mutant RARS protein-expressing cells, there were decreased phosphorylation levels of ribosomal S6 proteins (Fig. 7A and B). Together, these results suggest that mutant RARS proteins aggregate in the lysosome, possibly decreasing lysosome-related signaling. Protein phosphorylation array involved in lysosome-related signaling is also known to be required for oligodendroglial cell differentiation and myelination [21,22].

Fig. 7.

Expression of Ser456-to-Leu mutant constructs decreases phosphorylation of ribosomal S6 proteins in an oligodendroglial cell line. (A) FBD-102b cells were transfected with the plasmid encoding the mutant (green) and were immunostained with an anti-phospho-S6 antibody (red). The merged image is shown. Dotted outlines indicate the periphery of the transfected cells, which have exhibited decreased S6 phosphorylation (B) Percentages of phosphorylated S6 in cells expressing the mutant proteins or not are statistically shown (**, p < 0.01 of one-way ANOVA followed by a Fisher's protected least significant difference test as a post hoc comparison; n = 3 fields).

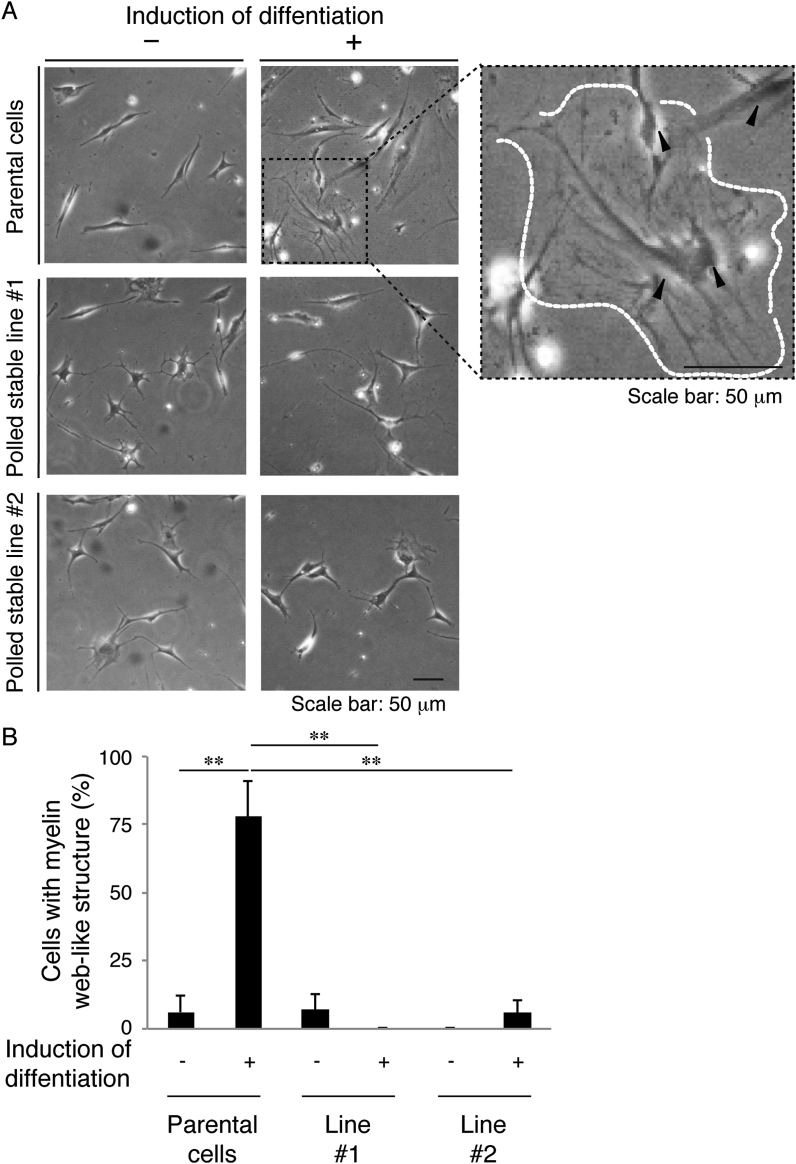

Finally, to clarify whether cells harboring mutant constructs undergo oligodendroglial differentiation, we isolated stable clones in FBD-102b cells and allowed the cells to differentiate. As expected, cells harboring mutant constructs failed to exhibit differentiated phenotypes with myelin web-like structures along oligodendroglial cell-like processes whereas parental cells exhibited them (Fig. 8A and B).

Fig. 8.

Cells harboring Ser456-to-Leu mutant constructs fail to exhibit differentiated phenotypes in FBD-102b cells. (A) Cells harboring mutant constructs (independently produced, polled stable lines #1 and #2) or parental cells were allowed to differentiate for 0 or 7 days (±the induction of differentiation). A magnified image of the upper right panel is shown, and a typical cell with myelin web-like structures along processes from the cell body is surrounded by a dotted outline. (B) After 0 or 7 days following the induction of differentiation, cells with myelin web-like structures were considered to be differentiated phenotypes (**, p < 0.01 of one-way ANOVA followed by a Fisher's protected least significant difference test as a post hoc comparison; n = 3 fields).

4. Discussion

HLD1 is responsible for point mutations or amplification/deletion of the plp1 gene. In the case of point mutations or amplification of the gene, the pathological causes are primarily due to stress signals evoked by ER-resident PLP1 proteins [[5], [6], [7], [8]]. RARS belongs to the cytoplasmic aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase family of proteins and ligates arginine to the cognate tRNA in cytoplasmic regions. In the present study, we for the first time show that HLD9-associated S456L mutant proteins of RARS exhibit some aggregated forms in polyacrylamide gels and are localized in lysosomes but not in ERs and Golgi bodies. Although it remains unclear whether the S456L mutation affects the enzymatic activities of RARS, mutated RARS proteins are not able to act as arginine-tRNA ligase in the cytoplasm. In this context, the S456L mutation is loss-of-function. Protein aggregation in neuropathies often triggers toxic effects on cells [7]. The established findings remind us of the relationship between mutated RARS proteins and toxic-gain-of-function. In either case, decreased expression levels of cytoplasmic RARS may also be linked to cellular pathological effects, such as inhibitory morphological differentiation.

Additionally, HLD4-associated mutations of mitochondrion-resident heat-shock protein D1 (HSPD1) affect the fusion and fission cycle of mitochondria and their mobility in the cytoplasm. HLD4 is not likely due to the aggregation of mutated HSPD1 [23,24]. It is thus predicted that cellular pathological phenomena are simply caused by the loss-of-function of HSPD1. Also, FAM126A (also called hyccin or Drctnnb1a) is a component of the phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase enzyme complex. FAM126A localizes a catalytic subunit of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase, which is probably required for myelin formation, to plasma membranes [25,26]. The Leu53-to-Pro (L53P) mutation in FAM126A causes HLD5 [27,28]. It is conceivable that HLD5-associated mutation of FAM126A decreases the localization of FAM126A to plasma membranes. We previously reported that the L53P mutant proteins accumulate in the ER but not in the Golgi body and the lysosome, triggering ER stress signals in COS-7 cells and in FAM126A (L53P)-transgenic mouse corpus callosum [29]. It is possible that some HLD-associated mutations, including HLD9-associated mutations, have effects on biochemical properties of the responsible gene-encoded proteins.

Misfolded or aged cytoplasmic proteins are usually hydrolyzed in lysosomes. The S456L mutant proteins of RARS are present in the lysosome without hydrolyzing. This may be due to the fact that, in addition to their increased aggregating activities, lysosomal enzyme hydrolyzing-resistant properties of RARS are acquired by the S456L mutation. Alternatively, the mutation may generate a de novo lysosome-resident protein. In fact, mutations of glycyl tRNA synthase (GARS), observed in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2D, generate proteins with de novo neuropilin-1 (Nrp1)-receptor-binding activities [30,31].

In this study, we also find that changes on RARS protein properties by the S456L mutation decrease lysosome-related S6 phosphorylation in the downstream of mTOR signaling. Since phosphorylation of S6 as well as of 4E-BP1, as the output of mTOR signaling, is needed for proper myelinating processes [21,22], it is predicted that decreased S6 phosphorylation be directly associated with defective oligodendroglial differentiation. Increased S6 phosphorylation may reverse cellular phenotypes in HLD9. By enhancing myelination or adding myelin bioorganic materials, some therapeutic procedures have been applied into cellular and mouse models of HLD1. For example, since cholesterol is the rate-limiting factor of myelin synthesis, treatment with cholesterol reverses HLD1 symptoms in mice [32]. There are also broad molecular and cellular pathological mechanism-based therapeutic procedures, such as inhibition of the ER stress signal [33,34].

Further studies on the effects of HLD9-associated mutation on molecular and cellular events, using primary cells or glial-neuronal co-cultures, will enhance our understanding not only of how mutation leads to RARS protein aggregation but also of how mutation triggers inhibitory oligodendrocyte differentiation leading to defect in myelin formation. The results of such research could be employed in the development of therapeutic target-specific medicines.

Funding sources

This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (17H03564 and 17K07127) and Branding projects (Tokyo University of Pharmacy and Life Sciences) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology. This work was also supported by Grants-in-Aid (27-2 and 29-16) for Medical Scientific Research from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Keiichi Homma (Maebashi Institute of Technology) for the insightful comments he provided throughout this study.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2019.100705.

Transparency document related to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2019.100705

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Transparency document

References

- 1.Simons M., Lyons D.A. Axonal selection and myelin sheath generation in the central nervous system. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2013;25:512–519. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2013.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morton P.D., Ishibashi N., Jonas R.A., Gallo V. Congenital cardiac anomalies and white matter injury. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:353–563. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2015.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saab A.S., Nave K.A. Myelin dynamics: protecting and shaping neuronal functions. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2017;47:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu-Rub M., Miller R.H. Emerging cellular and molecular strategies for enhancing central nervous system (CNS) remyelination. Brain Sci. 2018;8:E111. doi: 10.3390/brainsci8060111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garbern J., Cambi F., Shy M., Kamholz J. The molecular pathogenesis of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56:1210–1214. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.10.1210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dhaunchak A.S., Colman D.R., Nave K.A. Misalignment of PLP/DM20 transmembrane domains determines protein misfolding in Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:14961–14971. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2097-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin W., Lin Y., Li J., Fenstermaker A.G., Way S.W., Clayton B., Jamison S., Harding H.P., Ron D., Popko B. Oligodendrocyte-specific activation of PERK signaling protects mice against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J. Neurosci. 2013;33:5980–5991. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1636-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue K. Cellular pathology of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease involving chaperones associated with endoplasmic reticulum stress. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2017;4:7. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2017.00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biancheri R., Rosano C., Denegri L., Lamantea E., Pinto F., Lanza F., Severino M., Filocamo M. Expanded spectrum of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher-like disease: literature revision and description of a novel GJC2 mutation in an unusually severe form. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;21:34–39. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2012.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yakobov N., Debard S., Fischer F., Senger B., Becker H.D. Cytosolic aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases: unanticipated relocations for unexpected functions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Gene Regul. Mech. 2018;1861:387–400. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boczonadi V., Jennings M.J., Horvath R. The role of tRNA synthetases in neurological and neuromuscular disorders. FEBS Lett. 2018;592:703–717. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.12962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nafisinia M., Sobreira N., Riley L., Gold W., Uhlenberg B., Weiß C., Boehm C., Prelog K., Ouvrier R., Christodoulou J. Mutations in RARS cause a hypomyelination disorder akin to Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2017;25:1134–1141. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2017.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ji H., Li D., Wu Y., Zhang Q., Gu Q., Xie H., Ji T., Wang H., Zhao L., Zhao H., Yang Y., Feng H., Xiong H., Ji J., Yang Z., Kou L., Li M., Bao X., Chang X., Zhang Y., Li L., Li H., Niu Z., Wu X., Xiao J., Jiang Y., Wang J. Hypomyelinating disorders in China: the clinical and genetic heterogeneity in 119 patients. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0188869. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miyamoto Y., Yamauchi J., Tanoue A. Cdk5 phosphorylation of WAVE2 regulates oligodendrocyte precursor cell migration through nonreceptor tyrosine kinase Fyn. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:8326–8337. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1482-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyamoto Y., Yamauchi J., Chan J.R., Okada A., Tomooka Y., Hisanaga S., Tanoue A. Cdk5 regulates differentiation of oligodendrocyte precursor cells through the direct phosphorylation of paxillin. J. Cell Sci. 2007;120:4355–4366. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miyamoto Y., Torii T., Kawahara K., Inoue M., Morimoto T., Yamamoto M., Yamauchi J. Data on the effect of in vivo knockdown using artificial ErbB3 miRNA on Remak bundle structure. Data Brief. 2017;12:313–319. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsuneishi R., Matsumoto N., Itaoka M., Urai Y., Kaneko M., Watanabe N., Takashima S., Seki Y., Morimoto T., Sakagami H., Miyamoto Y., Yamauchi J. Data on the effect of knockout of cytohesin-1 in myelination-related protein kinase signaling. Data Brief. 2017;15:234–239. doi: 10.1016/j.dib.2017.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miyamoto Y., Torii T., Tago K., Tanoue A., Takashima S., Yamauchi J. BIG1/Arfgef1 and Arf1 regulate the initiation of myelination by Schwann cells in mice. Sci. Adv. 2018;4:eaar4471. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aar4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wyant G.A., Abu-Remaileh M., Wolfson R.L., Chen W.W., Freinkman E., Danai L.V., Vander Heiden M.G., Sabatini D.M. mTORC1 activator SLC38A9 is required to efflux essential amino acids from lysosomes and use protein as a uutrient. Cell. 2017;171:642–654. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sabatini D.M. Twenty-five years of mTOR: uncovering the link from nutrients to growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017;114:11818–11825. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1716173114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tyler W.A., Gangoli N., Gokina P., Kim H.A., Covey M., Levison S.W., Wood T.L. Activation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) is essential for oligodendrocyte differentiation. J. Neurosci. 2009;29:6367–6378. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0234-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bercury K.K., Dai J., Sachs H.H., Ahrendsen J.T., Wood T.L., Macklin W.B. Conditional ablation of raptor or rictor has differential impact on oligodendrocyte differentiation and CNS myelination. J. Neurosci. 2014;34:4466–4480. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4314-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miyamoto Y., Eguchi T., Kawahara K., Hasegawa N., Nakamura K., Funakoshi-Tago M., Tanoue A., Tamura H., Yamauchi J. Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy-associated missense mutation in HSPD1 blunts mitochondrial dynamics. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2015;462:275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.04.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyamoto Y., Kawahara K., Torii T., Yamauchi J. Defective myelination in mice harboring hypomyelinating leukodystrophy-associated HSPD1 mutation. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2017;11:6–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgmr.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baskin J.M., Wu X., Christiano R., Oh M.S., Schauder C.M., Gazzerro E., Messa M., Baldassari S., Assereto S., Biancheri R., Zara F., Minetti C., Raimondi A., Simons M., Walther T.C., Reinisch K.M., De Camilli P. The leukodystrophy protein FAM126A (hyccin) regulates PtdIns(4)P synthesis at the plasma membrane. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;18:132–138. doi: 10.1038/ncb3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alvarez-Prats A., Bjelobaba I., Aldworth Z., Baba T., Abebe D., Kim Y.J., Stojilkovic S.S., Stopfer M., Balla T. Schwann-cell-specific deletion of phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase α causes aberrant myelination. Cell Rep. 2018;23:2881–2890. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zara F., Biancheri R., Bruno C., Bordo L., Assereto S., Gazzerro E., Sotgia F., Wan X.B., Gianotti S., Stringara M., Pedemonte M., Uziel G., Rossi A., Schenone A., Tortori-Donati P., van der Knaap M.S., Lisanti M.P., Minetti C. Deficiency of hyccin, a newly identified membrane protein, causes hypomyelination and congenital cataract. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1111–1113. doi: 10.1038/ng1870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ugur S.A., Tolun A.A. Deletion in DRCTNNB1A associated with hypomyelination and juvenile onset cataract. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2008;16:261–264. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miyamoto Y., Torii T., Eguchi T., Nakamura K., Tanoue A., Yamauchi J. Hypomyelinating leukodystrophy-associated missense mutant of FAM126A/hyccin/DRCTNNB1A aggregates in the endoplasmic reticulum. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2014;21:1033–1039. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2013.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.He W., Bai G., Zhou H., Wei N., White N.M., Lauer J., Liu H., Shi Y., Dumitru C.D., Lettieri K., Shubayev V., Jordanova A., Guergueltcheva V., Griffin P.R., Burgess R.W., Pfaff S.L., Yang X.L. CMT2D neuropathy is linked to the neomorphic binding activity of glycyl-tRNA synthetase. Nature. 2015;526:710–714. doi: 10.1038/nature15510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sleigh J.N., Dawes J.M., West S.J., Wei N., Spaulding E.L., Gómez-Martín A., Zhang Q., Burgess R.W., Cader M.Z., Talbot K., Yang X.L., Bennett D.L., Schiavo G. Trk receptor signaling and sensory neuron fate are perturbed in human neuropathy caused by Gars mutations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017;114:E3324–E3333. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1614557114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saher G., Rudolph F., Corthals K., Ruhwedel T., Schmidt K.F., Löwel S., Dibaj P., Barrette B., Möbius W., Nave K.A. Therapy of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease in mice by feeding a cholesterol-enriched diet. Nat. Med. 2012;18:1130–1135. doi: 10.1038/nm.2833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin W., Popko B. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in disorders of myelinating cells. Nat. Neurosci. 2009;12:379–385. doi: 10.1038/nn.2273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yu L.H., Morimura T., Numata Y., Yamamoto R., Inoue N., Antalfy B., Goto Y., Deguchi K., Osaka H., Inoue K. Effect of curcumin in a mouse model of Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2012;106:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.