Abstract

Endoscopic technique in patients undergoing chronic ear surgery allows visualization of protympanic (proximal) segment of the Eustachian tube (ET). The proximal cartilaginous ET is a common site of anatomical Obstruction in chronic otitis media and it is this proximal end of ET that is being observed, instrumented and dilated with transtympanic methods. The aim of this article is to discuss our approach to the assessment of the Eustachian tube using opening pressure measurement, endoscopic assessment of the protympanic segment of ET and Valsalva CT. And also to discuss detailed technique of transtympanic Eustachian tube dilatation.

Keywords: Endoscopic ear surgery, Eustachian tube, Transtympanic balloon dilatation, Carotid canal, Protympanum

Introduction

Persistent Eustachian tube dysfunction is most often correlated with failures in surgery for chronic ear disease.1 There are no defined and reliable guidelines for assessing Eustachian tube function prior to surgery.2 Also the criteria for measuring surgical success are inconsistent across multiple studies, with outcomes often consisting of non-validated subjective scoring systems.3, 4, 5 The anatomic patency of the tube can be assessed by testing for opening pressure6 and further localization of possible obstruction obtained by Valsalva CT and endoscopic evaluation of protympanum during ear surgery.7

Trans-nasal balloon dilatation of the Eustachian tube has been recently introduced as a novel, minimally invasive and safe method for treating obstructive Eustachian tube dysfunction.8,9 It involves dilatation of the cartilaginous portion of the ET via the nasopharynx with a balloon catheter. Safety consideration in regard to avoiding possible injury to the carotid artery has limited the area of instrumentation to the distal end of the tube, probably the least likely obstructed segment.7,10,11

Endoscopic ear surgery allows for access and visualization of the protympanic segment of the ET, carotid canal and there had been earlier studies showing obstruction in the proximal (tympanic) end of ET.10, 11, 12 Transtympanic introduction of the balloon catheter beyond the carotid canal into the cartilaginous ET would assure the safety of the dilatation along with the dilatation coverage of a wider segment of the cartilaginous tube.13

Materials & methods

We have devised 3 techniques to evaluate patency of the Eustachian tube in patients undergoing surgery for chronic ear disease;

-

1.

Measuring the opening pressure of the Eustachian tube preoperatively and intraoperatively

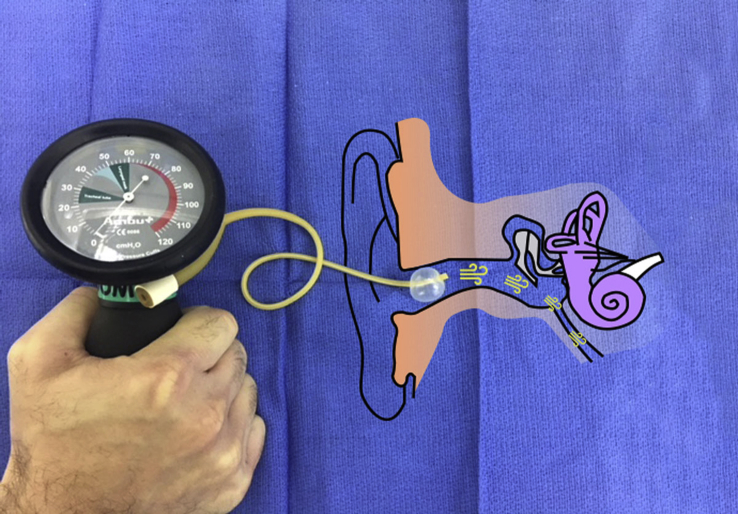

Opening pressure of the ET is measured in the outpatient clinic for patients with tympanic membrane perforation (with no active infection). For remaining patients of tympanic membrane retraction and cholesteatoma, opening pressure measurement of the ET is done intraoperatively. Measurements are performed using number 8 French Foley's catheter, cutting its tip beyond the balloon, inserting it, lodging it, and inflating the balloon in the ear canal to seal it off (Fig. 1). Then, using an endotracheal tube cuff pressure gauge (Ambu AS, Denmark), the pressure was increased in the lumen of catheter (and therefore in the tympanic cavity, since the ear canal was sealed by the balloon) until it precipitously drops indicating the opening of the Eustachian tube and leakage of air into the nasopharynx. If the Eustachian tube does not open at a maximum of 100 cm of H2O, then no further measurements are taken. If the Eustachian tube opens up higher than 50 cm of H2O, then a secondary opening pressure (immediate 2nd measurement) is done and is recorded.

Fig. 1.

Set up for measuring opening-pressure of Eustachian-tube: Sealing of ear is performed with Number 8 Foley's catheter and application of pressure is done by endotracheal tube cuff pressure monitoring device.

Intra-operative measurement of the opening pressure is done as described above after local infiltration of ear canal skin with xylocaine and 1/60000 epinephrine, elevation of tympanomeatal flap, removal of all gross disease in the anterior mesotympanum, and before any extensive dissection or disease removal elsewhere. We elected to limit the pressure of insufflation to 100 CM of H2O and to do the measurements and dilatations early on in the course of chronic ear surgery procedure in order to prevent the possibility of air embolization.

We assumed presence of obstruction and decided on dilatation based on a secondary opening pressure more than 50 cm of H2O. Previously reported data on healthy subjects showed a secondary opening pressure of 35 ± 10 cm of H2O.14 We felt that our threshold of >50 cm of H2O roughly approximates the <55 cm of H2O value (μ + 2σ) for the 95% of healthy middle ear and Eustachian tubes.

-

2.

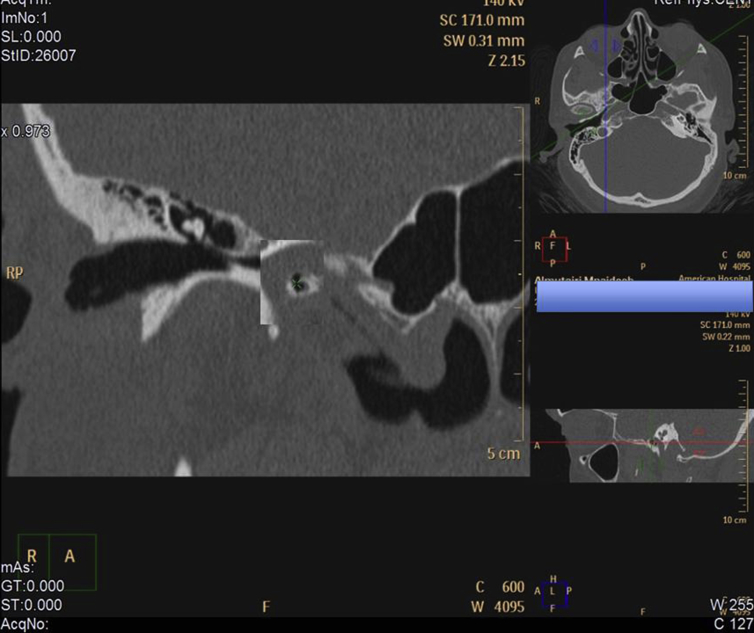

Valsalva CT

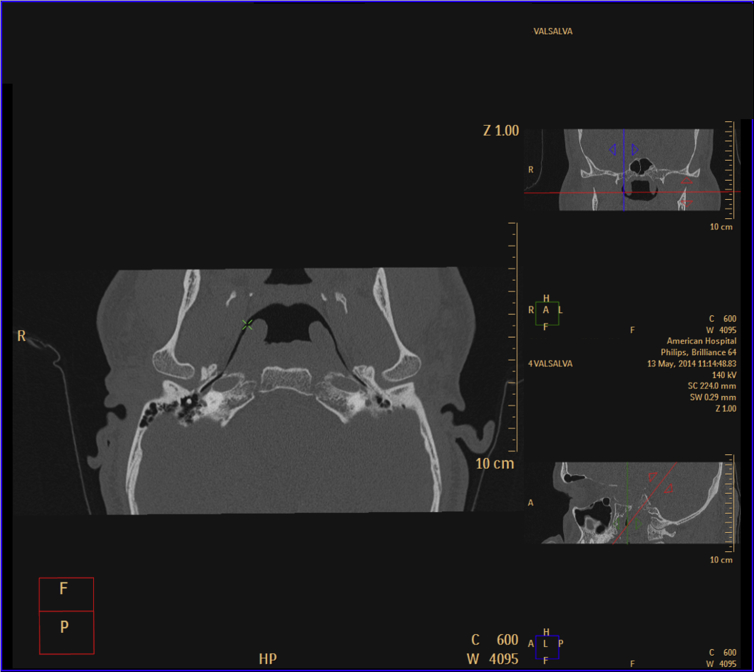

Patients with chronic ear disease and suspected ET obstruction were asked to perform Valsalva CT. Valsalva CT of the temporal bone is performed while the patient is actively performing Valsalva maneuver (concurrent with the examination). The technician was instructed to ask the patient to perform forceful exhalation against a closed nose. Individual patient instruction was done by the technician just prior to CT. Primary image acquisition was made in the supine in the helical mode. Overlapping, 0.67 mm (thickness) × 0.5 mm (increment), axial dataset was obtained. Multiplanar reconstruction of the images in the axis of the eustachian tube was performed. This was done by utilizing image reconstruction proprietary software on the CT scanner workstation (Phillips Brilliance 64; Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands). The following methodology was applied: the rotation center (crosshair) was positioned at the fundus of the nasopharyngeal end of the eustachian tube on axial sections. Looking at the sagittal view, the axial plane was then tilted anteroinferiorly until the whole length of the tube was visualized. Further attempts were made by minor adjustments of all the planes to get the longest segment of the dilated/visualized cartilaginous tube (Fig. 2).

-

3.

Endoscopic evaluation of protympanum during surgery

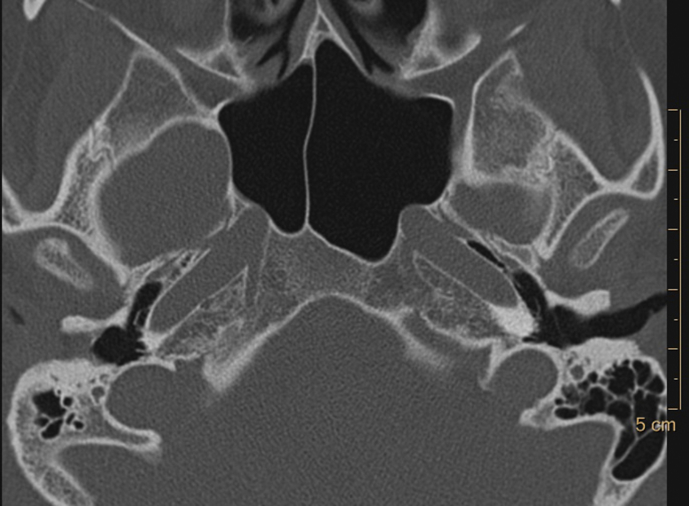

Fig. 2.

Screenshot of CT workstation with full visualization of the whole length of the ET on multi-planar reconstruction.

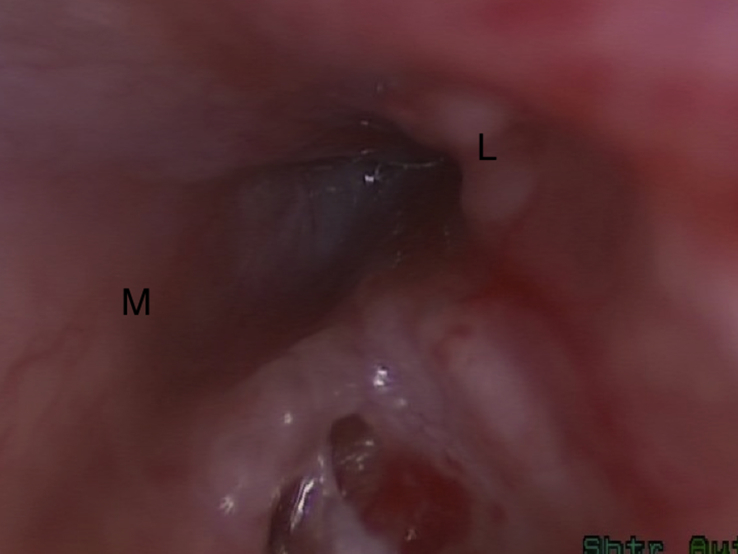

If the secondary opening pressure of the ET is higher than 50 cm of water, then, endoscopic evaluation of the protympanum is performed using 30°, 3 mm, 15 cm rigid endoscope that is introduced anterior to the handle of malleus into the anterior upper quadrant of the tympanic ring after detaching the tympanic membrane remnant from the handle of malleus. The protympanic segment is then assessed for clear impression of the carotid artery canal, presence of blind pouches and for evidence of obstruction beyond that (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Right ear: View of the obstructed protympanic segment of the Eustachian tube. (M - medial, L-lateral).

Technique of transtympanic Eustachian tube dilatation

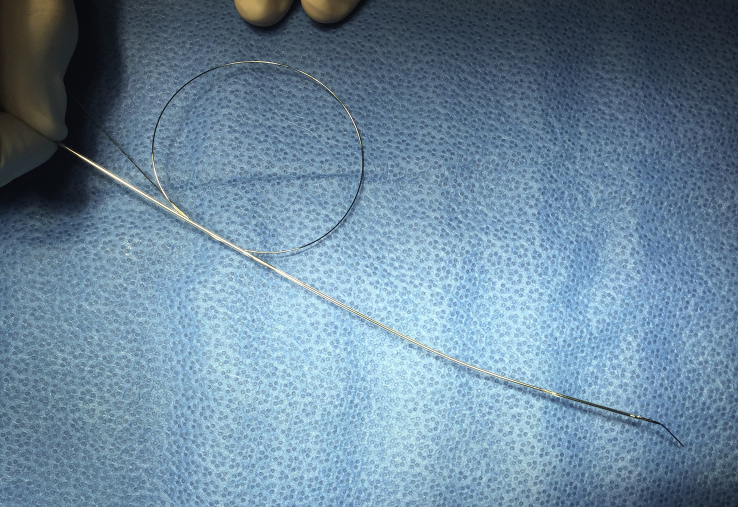

Eustachian tube balloon dilatation catheter (Spiggle & Theis, Germany) is used. The catheter is usually shipped with a metal stylet that runs within the catheter. At about 1 cm from the tip of the catheter, the stylet is bent to approximately 30° (Fig. 4). The stylet functions like a guide wire and the catheter is fed into the Eustachian tube over the stylet until it is well within the tube and the stylet is then removed. The balloon is then inflated by infusing saline slowly up to 10 bar pressures. Given the V-like shape of the tube with the nasopharyngeal end being much larger than the proximal end, as the balloon is inflated, the surgeon will experience “catheter pull in” to the nasopharyngeal end of the tube (Fig. 5). This would confirm to the surgeon that the catheter is located within the Eustachian tube. If the catheter is located in a blind pouch, the surgeon would experience the opposite effect, with “catheter pull out” upon inflation of the balloon. Before inflating balloon, surgeon should confirm that balloon is not occupying any blind pouch and its well beyond clear impression of the carotid artery canal. After documenting the “the catheter pull in”, the balloon is deflated and pulled out by 5 mm increments and repeatedly inflated until the balloon is lodged at the isthmus and the “catheter pull in” phenomenon stops. This indicates that it has engaged the isthmus of the tube. The balloon is kept inflated for 2 min at 10 bar pressure. Re-inspection of the protympanum with a 3 mm 30° endoscope is performed to assess for change of aperture of the Eustachian tube. Then the opening pressure is tested again using previously described methodology. Appropriate further removal of disease from other areas of the tympanic and mastoid cavity and reconstruction is then performed as per established surgical practices. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and the ethics committee at the American Hospital Dubai approved this study.

Fig. 4.

The stylet is angled at distal end and proximal end is looped so it can be rotated to direct distal end angled tip toward the opening of the Eustachian tube.

Fig. 5.

3D reconstruction of airspaces in temporal bone in a Valsalva CT showing V like shape of Eustachian tube, and the “catheter pull in” that happens when the balloon is inflated.

Results

Transtympanic dilatation of the ET is a safe and atraumatic intervention. In over 100 dilatation procedures performed by the senior author, there were almost no bleeding or mucosal lacerations evident on immediate inspection of the protympanum and the dilated proximal segment. All patients had pre-dilatation opening pressure above 50 cm of H2O including 10 of them who did not have any opening of the Eustachian tube even with maximum applied pressure of 100 cm of water. Dilatation of proximal cartilaginous Eustachian tube was technically possible in all except 3 patients. In these 3 patients, the catheter could not be advanced into the Eustachian tube due to anatomical considerations. All patients undergoing successful dilatation had endoscopic evidence of significant change of aperture when comparing pre and post dilatation endoscopic examination. The opening pressure was consistently lower subsequent to dilatation in all but one patient who had persistent failure to open the Eustachian tube after dilatation. There were no facial nerve injuries and carotid artery related complications.

2 patients had repeated attempts and clear difficulties in intubating the Eustachian tube and both these patients suffered from post-operatively severe disabling dizziness. One of these patients had cochlear loss and persistent tinnitus despite of corticosteroids treatment. The other patient had subluxation of stapes during attempted insertion and subsequent looping of the catheter in the tympanic cavity and displacement of stapes in the vestibule. A piece of fat tissue was applied and was supported with bed of gel foam. Patient had severe dizziness for two days, with no change in bone conduction thresholds. In few patients, post dilatation CT was obtained 3–4 months after procedure and evidence of increased patency in the protympanic area were observed (Fig. 6, Fig. 7).

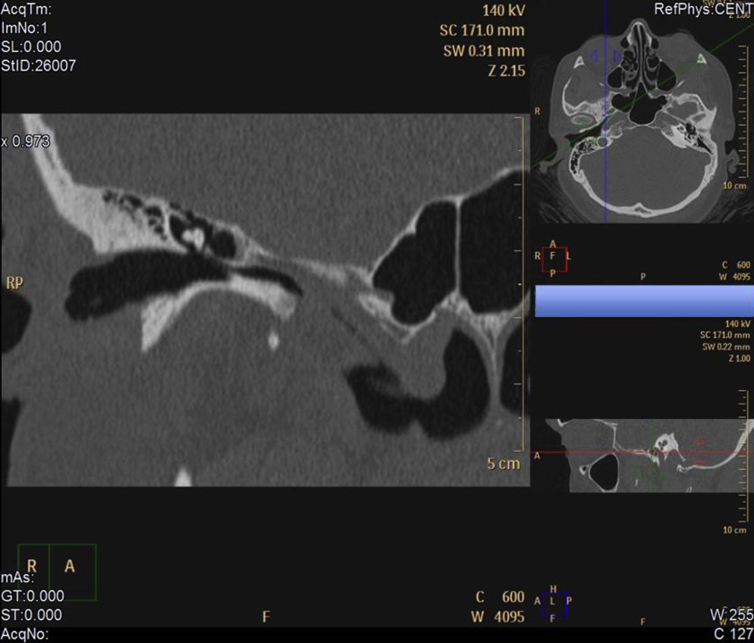

Fig. 6.

Preoperative CT of the protympanic segment of Eustachian tube.

Fig. 7.

Postoperative CT of the protympanic segment in the same patient at three month from intervention.

Discussion

The Eustachian tube (ET) is a conduit between the middle ear space and the nasopharynx, which opens in a physiologically complex and poorly understood manner to provide ventilation to the middle ear, and also to equalize middle ear and ambient pressures. Since its first description by Bartolomeo Eustachi in 1563, the concept of the eustachian tube as partly bony structure has taken deep roots in our understanding of its anatomy, function and possible dysfunction. Microscopic and gross anatomical observations of the “bony tube” have made a distinction between “the protympanum,” a tympanic cavity structure, and a more anterior and inaccessible “bony Eustachian tube.”

The advent of endoscopic ear surgery provides an opportunity for examination and possible interventions directed at those anterior structures including the protympanum and the proximal part of the cartilaginous ET.

Endoscopic observation of that area allows a very different view of anatomy and renders this distinction arbitrary and irrelevant. Indeed, by observing the protympanum from this perspective, it is clear that the bony Eustachian tube and the protympanum are essentially one and the same. We believe that this calls for a redefinition the Eustachian tube as a fibrous/cartilaginous structure that stretches from the nasopharynx to the most anterior part of the tympanic cavity (the protympanum along with what used to be referred to as bony tube).15, 16, 17 This clear anatomic redefinition is critical for any further observations and instrumentation in that area. What used to be described as a junctional area of the Eustachian tube is really the most proximal (tympanic-end) segment of that cartilaginous Eustachian tube surrounded by the bony encasement of the petrous bone or the “Protympanum”. In our opinion, it is this proximal (tympanic) end of the cartilaginous eustachian tube that is being observed, instrumented and dilated with transtympanic methods.

There are no specific tests of ET function in widespread clinical use, and no identified ‘gold standard’ with which to diagnose the disease. Most of the testing methods that have been devised for the Eustachian tube function are not anatomically based and indirect methods that do not locate the site of obstruction.2 In normal physiologic conditions, the Eustachian tube opens up as a result of a combination of direct muscle action and indirect action by increased nasopharyngeal pressure beyond the opening pressure of the tube.18 Improved CT technology with spiral CT has resulted in a very short imaging time that allows the patient to maintain Valsalva maneuver throughout the examination and also multiplanar reconstruction allows for orienting the plane in the desired way as to match and sloping position of the Eustachian tube. Visualization of the whole length of the cartilaginous tube with Valsalva is usually observed in almost a third of the normal population.7 Valsalva maneuver increases the length of the visualized segment and extended it to include the distal one third of the tube. Therefore, collapsed distal tube despite adequate performance of Valsalva maneuver during CT would indicate distal Eustachian tube obstruction. In clinical practice, this is consistently observed in association with enlarged adenoids filling the fossa of Rosenmueller and collapsing the torus tubularis anteriorly. This represents a rather unusual etiology of Eustachian tube obstruction in patients with chronic otitis media.10

With the advent of endoscopic sinus surgery and improved access and visualization of the nasopharynx, there has been increased interest in the visualization and possible instrumentation of the distal nasopharyngeal end of the Eustachian tube. Many procedures have been devised to try to address underlying obstruction in that area. These techniques are predicated on two principles; the first is an assumption that obstructive pathology is located within the nasopharyngeal-end of the Eustachian tube, and this assumption is based on physiological tests which only demonstrate that the ET is obstructed but fails to anatomically locate the obstructed segment. The second is that to avoid carotid complications, the catheter should not advance beyond the isthmus. This safety concern was addressed by different design features that either limits the length of the catheter that can be introduced or by adding a bulbous tip that prevent further advance into the isthmus of the tube. Our transtympanic route of introducing the catheter is driven by our belief that both of these assumptions are wrong. We had previously reported data showing that the site of obstruction in the chronic ear surgery population exists in the proximal (tympanic-end) of the Eustachian tube.11 Linstrom reported similar findings earlier when he routinely examined the protympanum in similar patient group.12 In both studies, the nasopharyngeal-end of the tube was widely patent.

Given the limited microscopic access to the protympanum, it has been the common wisdom in the otology community to stay away from any interventions involving the proximal ET given its proximity to the carotid artery. Further confirmation of that close relationship is found on the axial plane CT images, the carotid is very prominent and appears in close proximity to the whole length of the Eustachian tube (Fig. 8). However, in reality, all of the cartilaginous tube is well away from the carotid artery as it turns downward toward the nasopharynx (Fig. 9). Fig. 10 is Parasagittal multiplanar reconstruction of the CT taken in the plane of the Eustachian tube defining the downward slope of the cartilaginous tube. Fig. 11 is the same image as Fig. 10 but with an overlay of the carotid artery course obtained from a parallel section just medial to Fig. 10. It confirms that the carotid artery takes a very different direction and intersects with only a limited segment of the medial aspect of the protympanic bony segment of the tube. The safety of the carotid and its canal can be ascertained due to the consistency of the identification of the carotid canal in the medial wall of the protympanum and the introduction of the balloon catheter beyond that point as well as the different steps in the technique that we outlined earlier to confirm the catheter location within the Eustachian tube.

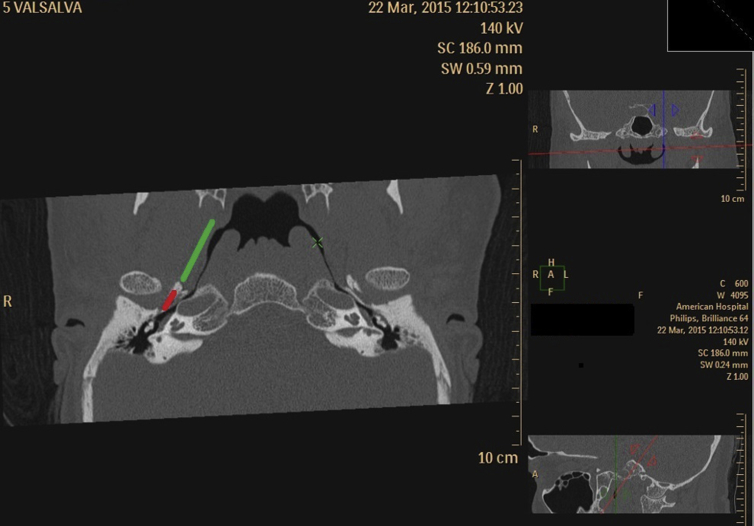

Fig. 8.

Axial CT of the protympanum depicting that much of the medial wall of the tube is occupied by the carotid artery.

Fig. 9.

Reconstructed CT images in the plane of the Eustachian tube showing visualization of the whole length of the tube on both sides. The whole cartilaginous tube and part of the bony segment is well clear of carotid (green line) and the carotid proximity to the Eustachian tube is limited to a certain area within the bony part (red line).

Fig. 10.

Parasagittal multiplanar reconstruction in the axis of the tube showing the downward orientation of the cartilaginous tube.

Fig. 11.

The same plane as in Fig. 10, but with an overlay of the carotid artery course obtained from another image parallel to the one showed in 10 but more medial to show the carotid.

Also there have been three cadaveric studies published on the safety of endoscopic guided transtympanic dilatations.19, 20, 21 The earlier cadaveric study showed significant risk to the carotid but was based on blind introduction of the catheter into the protympanum without any endoscopic control.20 Two later cadaveric studies, including one of our own, were done under endoscopic control and did not show any damage to carotid canal on post dilatation CT scan.20,21 Our own clinical experience detailed here did not show any carotid complications.

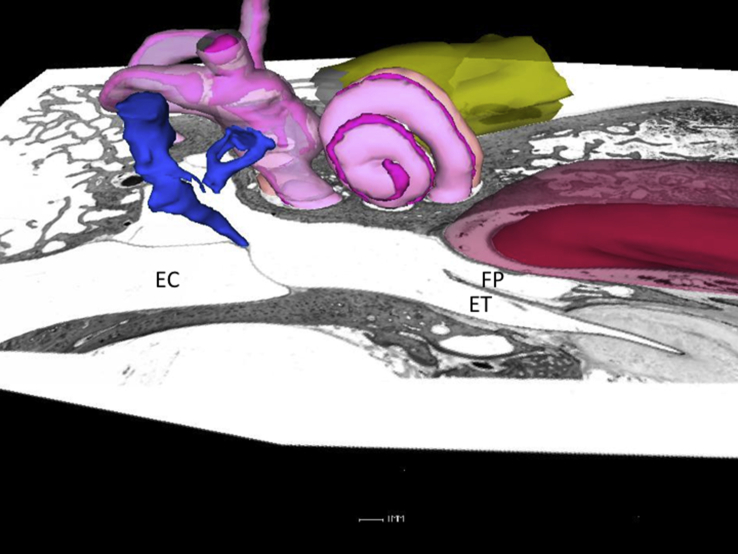

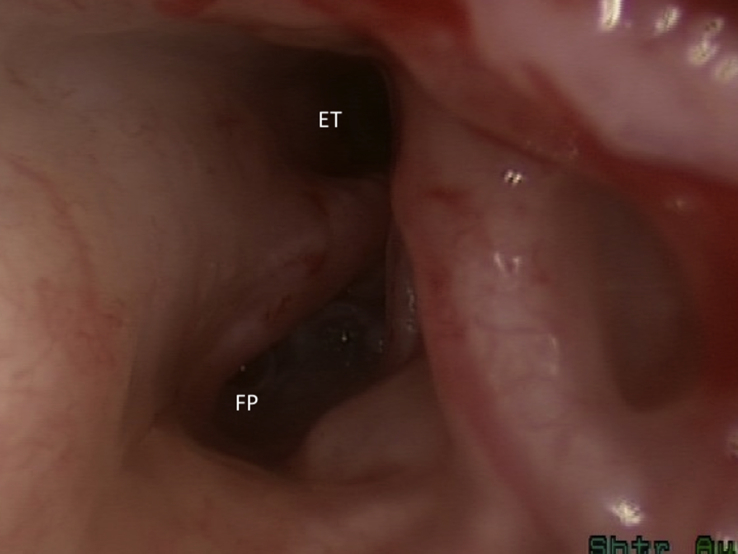

The anatomy of the protympanic segment of the Eustachian tube is variable and clear understanding of that anatomy and full visualization is a precondition to safe instrumentation of the proximal end the Eustachian tube. In about 30% of the ears examined, there was a pneumatization of the space, the area anterior to the carotid which resulted in ridge of bone that separated the protympanic opening of the Eustachian tube into a lateral opening for the Eustachian tube and a medial false passage (Fig. 12). This requires the surgeon to introduce a small scope far enough anteriorly to determine the exact anatomy of that area (Fig. 13, Fig. 14). If the false passage is cannulated, and if the surgeon fails to clearly identify the carotid canal and to ascertain the intubation of the Eustachian tube anterior to the canal, one can see the possibility of doing damage to the carotid canal.

Fig. 12.

Axial histological section of the temporal bone with the cochlea and malleus simulated for orientation. Note the pneumatization and formation of a medial false passage. ET: Eustachian Tube; FP: False Passage.

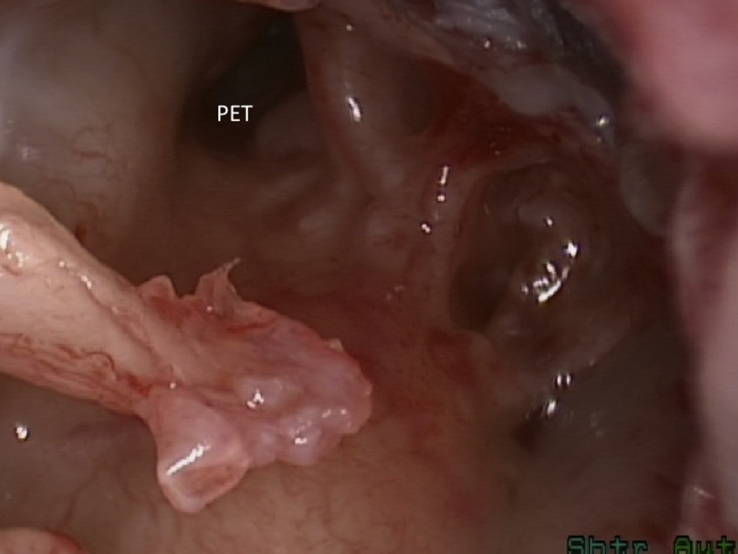

Fig. 13.

Right ear: the protympanum is visualized after lifting of the tympanic membrane off the handle of the malleus. An apparent opening of the Eustachian tube is visualized. (PET- Protympanum).

Fig. 14.

Further introduction of the scope shows the true opening of the Eustachian tube laterally to a false passage that was initially thought to be the opening of the tube. (ET: Eustachian Tube; FP: False Passage).

In our case series, 2 patients developed post-operatively severe dizziness. One of these patients had subluxation of stapes due to coiling of the catheter inside the tympanic cavity on multiple attempts to cannulate the ET. These two cases have consolidated in our mind the importance of endoscopic monitoring of the whole procedure and not just during the initial introduction of the catheter. Since then, we adopted a two surgeon approach with one surgeon holding the endoscope and the other surgeon holding and advancing the catheter under endoscopic monitoring.

Our results showed that the high opening pressure in some of our patients with chronic ear disease is related to obstructive pathology within the tympanic end of the tube. In almost every patient, the dilatation of the proximal (tympanic-end) Eustachian tube was associated with a precipitous drop in the opening pressure immediately after dilatation.22 It underscores and confirms our previous observation on the location of obstructive Eustachian tube pathology in patients undergoing chronic ear surgery.11

Conclusion

Mechanical Obstruction of the Eustachian tube is reasonably common finding in chronic ear surgery and need to be assessed preoperatively by Valsalva CT and opening pressure measurement. Intraoperative inspection of the protympanic segment of the Eustachian tube is possible and might lead to clear determination of the site of obstruction. Transtympanic dilatation of ET is feasible and is not associated with the commonly anticipated carotid complications however, continuous endoscopic control is essential to avoid trauma to middle ear structures.

Sponsorships

None.

Funding source

None.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None.

Edited by Xin Jin

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of Chinese Medical Association.

References

- 1.Sato H., Nakamura H., Honjo I., Hayashi M. Eustachian tube function in tympanoplasty. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1990;471:9–12. doi: 10.3109/00016489009124803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Todd N.W. There are no accurate tests for eustachian tube function. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;126:1041–1042. doi: 10.1001/archotol.126.8.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silvola J., Kivekäs I., Poe D.S. Balloon dilation of the cartilaginous portion of the Eustachian tube. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;151:125–130. doi: 10.1177/0194599814529538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Catalano P.J., Jonnalagadda S., Yu V.M. Balloon catheter dilatation of Eustachian tube: a preliminary study. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:1549–1552. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e31826a50c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jurkiewicz D., Bień D., Szczygielski K., Kantor I. Clinical evaluation of balloon dilation Eustachian tuboplasty in the Eustachian tube dysfunction. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:1157–1160. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2243-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holmquist J. Acoustic impedance and admittance -the measurement of middle ear function. In: Feldman A., Wilber L., editors. Eustachian tube evaluation. Williams and Wilkins; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tarabichi M., Najmi M. Visualization of the eustachian tube lumen with Valsalva computed tomography. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:724–729. doi: 10.1002/lary.24979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poe D. In reference to Balloon dilatation Eustachian tuboplasty: a clinical study. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:908. doi: 10.1002/lary.21138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poe D.S., Hanna B.M. Balloon dilation of the cartilaginous portion of the Eustachian tube: initial safety and feasibility analysis in a cadaver model. Am J Otolaryngol. 2011;32:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tarabichi M., Najmi M. Site of eustachian tube obstruction in chronic ear disease. Laryngoscope. 2015;125:2572–2575. doi: 10.1002/lary.25330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Linstrom C.J., Silverman C.A., Rosen A., Meiteles L.Z. Eustachian tube endoscopy in patients with chronic ear disease. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1884–1889. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200011000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tarabichi M. Transcanal endoscopic management of cholesteatoma. Otol Neurotol. 2010;31:580–588. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0b013e3181db72f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tarabichi M., Najmi M. Transtympanic dilatation of the eustachian tube during chronic ear surgery. Acta Otolaryngol. 2015;135:640–644. doi: 10.3109/00016489.2015.1009640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moon J.B., Swanson S.A. Passive eustachian tube opening pressure. Its measurement, normal values, and clinical implications. Arch Otolaryngol. 1983;109:364–368. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1983.00800200010004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tarabichi M., Kapadia M. The role of transtympanic dilatation of the Eustachian tube during chronic ear surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49:1149–1162. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2016.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jufas N., Marchioni D., Tarabichi M., Patel N. Endoscopic anatomy of the protympanum. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49:1107–1119. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2016.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarabichi M., Kapadia M. Preoperative and intraoperative evaluation of the Eustachian tube in chronic ear surgery. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49:1135–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elner A., Ingelstedt S., Ivarsson A. The normal function of the Eustachian tube. A study of 102 cases. Acta Otolaryngol. 1971;72:320–328. doi: 10.3109/00016487109122489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kepchar J., Acevedo J., Schroeder J., Littlefield P. Transtympanic balloon dilatation of Eustachian tube: a human cadaver pilot study. J Laryngol Otol. 2012;126:1102–1107. doi: 10.1017/S0022215112001983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jufas N., Treble A., Newey A., Patel N. Endoscopically guided transtympanic balloon catheter dilatation of the Eustachian tube: a cadaveric pilot study. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37:350–355. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kapadia M., Tarabichi M., Najmi M., Hamza M. Safety of carotid canal during transtympanic dilatation of the Eustachian tube: a cadaver pilot study. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018 Jun;70:211–217. doi: 10.1007/s12070-017-1063-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kapadia M., Tarabichi M. Feasibility and safety of transtympanic balloon dilatation of Eustachian tube. Otol Neurotol. 2018;39:e825–e830. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]