Abstract

Pakistani women in the UK are an at‐risk group with high levels of mental health problems, but low levels of mental health service use. However, the rates of service use for Pakistani women are unclear, partly because research with South Asian women has been incorrectly generalised to Pakistani women. Further, this research has been largely undertaken within an individualistic paradigm, with little consideration of patients’ social networks, and how these may drive decisions to seek help. This systematic review aimed to clarify usage rates, and describe the nature of Pakistani women's social networks and how they may influence mental health service use. Ten journal databases (ASSIA, CINAHL Plus, EMBASE, HMIC, IBSS, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Social Sciences Abstracts, Social Science Citation Index and Sociological Abstracts) and six sources of grey literature were searched for studies published between 1960 and the end of March 2014. Twenty‐one studies met inclusion criteria. Ten studies (quantitative) reported on inpatient or outpatient service use between ethnic groups. Seven studies (four quantitative, three qualitative) investigated the nature of social networks, and four studies (qualitative) commented on how social networks were involved in accessing mental health services. Pakistani women were less likely than white (British) women to use most specialist mental health services. No difference was found between Pakistani and white women for the consultation of general practitioners for mental health problems. Pakistani women's networks displayed high levels of stigmatising attitudes towards mental health problems and mental health services, which acted as a deterrent to seeking help. No studies were found which compared stigma in networks between Pakistani women and women of other ethnic groups. Pakistani women are at a considerable disadvantage in gaining access to and using statutory mental health services, compared with white women; this, in part, is due to negative attitudes to mental health problems evident in social support networks.

Keywords: ethnic minorities, mental health services, Pakistani, social support, stigma

What is known about this topic

Pakistani women in the UK have high levels of mental health problems, but their rate of mental health service use has not been clearly established.

Social networks can increase or decrease service use, but this association has not been investigated in the UK.

What this paper adds

Pakistani women were less likely than white women to use specialist mental health services, but were no less likely to consult general practitioners for mental health problems.

High levels of mental health stigma were evident in Pakistani women's social networks and acted as a deterrent to using services, but no studies were identified that compared stigma across ethnic groups.

Introduction

The Delivering Race Equality programme (Department of Health, 2005) aimed to provide equitable, non‐racist mental health services to people in England and Wales. Its success was limited and after its end in 2010, ethnic inequalities in mental health service provision remained (Community and Mental Health Team: Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2014a). South Asian (Pakistani, Indian and Bangladeshi) women are one group for whom inequalities (low rates of usage of mental health services) are evident (C. Cooper et al. 2013, J. Cooper et al. 2010). Within this group, Pakistani women may be particularly disadvantaged, as they have high levels of mental illness (Gater et al. 2009, Chaudhry et al. 2012), but low levels of service use. However, there is little robust evidence, as typically the rates of usage for Pakistani women have been inferred from South Asian women. It is not appropriate to do this, as there are indications that Pakistani women have higher mental illness rates than Indian and Bangladeshi women (Nazroo 2001, Weich et al. 2004), but lower usage of mental health services than Indian women (Care Quality Commission & National Mental Health Development Unit, 2010, 2011).

Pakistani women may have low mental health service use because they are less likely to be referred to specialist mental health services (Burman et al. 2002) and the National Health Service (NHS) may be inadequate in addressing religious, cultural and language needs (Chew‐Graham et al. 2002, Bowl 2007). Further, Pakistani women may be fearful that confidentiality may not be maintained (Gilbert et al. 2004). These reasons reflect the tendency of research on mental health service use to focus on how individuals (patients) in conjunction with systems (NHS) drive the outcomes of mental healthcare pathways. Therefore, unsurprisingly, the candidacy model (Dixon‐Woods et al. 2005), has been the theoretical model of choice for many recent reviews of health service usage (Garrett et al. 2012, Lamb et al. 2012). This model largely ignores the social aspect of help‐seeking; the way in which decisions and actions are influenced by the people closest to us (Pescosolido 1992, 2011, Thornicroft 2006). Social networks may be particularly important for those groups who are alienated from mental health service systems, both in terms of their content (the people in them – friends, family), and their function (provision of support, exchange of information about illness and services). Social support within social networks may be protective, by reducing the propensity to develop mental illness, and for people who have developed mental illness, social networks may act as a substitute for services (Gourash 1978). Certainly, research in the US, Netherlands and Puerto Rico has shown that people were less likely to use mental health services if high levels of support were being provided within networks (Pescosolido et al. 1998, Ten Have et al. 2002, Maulik et al. 2009). However, in the UK, very little attention has been paid to the influence (either positive or negative) of the content and function of social networks on the usage of mental health services. This is an important omission, as research from other countries suggests that the explanations for low rates of mental health service use could be expanded upon and improved with reference to the content and function of social networks. In order to clarify the rates of usage of mental health services of Pakistani women, the nature of their social networks and the possible influence of social networks on mental health service use, the review answered these questions:

How does the usage of mental health services for Pakistani women in the UK compare with women from other ethnic groups?

What is the nature of Pakistani women's social networks and how does this compare with women from other ethnic groups?

What are the reasons for the mental health services usage patterns of Pakistani women and are social networks involved in the help‐seeking and access process?

Methods

The review included quantitative and qualitative research studies. Mixed‐methods studies were not excluded, but there were not any mixed‐method studies that were deemed to be of sufficient quality to be included. Reviews incorporating quantitative and qualitative research have become more widely used in the social sciences (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co‐ordinating Centre (EPPI‐Centre), 2010). For this review the data from studies were analysed thematically within each research question. It was not the intention of the review to generate a new theory of access to mental healthcare services, as there have been many studies that have already looked at this in‐depth, conceptually (Pescosolido 1992, Dixon‐Woods et al. 2005). Instead the review aimed to clarify the mental health usage rates for Pakistani women, and establish whether social networks are involved in the help‐seeking process.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were: studies published from 1960 up to the end of March 2014, pertaining to Pakistani or South Asian women, on the subject of either access to, or usage of, mental health services or the nature of social networks, conducted in the UK and written in English. Studies from other countries were excluded due to the differing migration histories, socioeconomic positions and mental illness rates of Pakistani women in other countries. Papers that were theoretical in nature were excluded. Studies were excluded if they investigated access to child and adolescent mental health services, as the help‐seeking process that parents undertake on behalf of children is not directly comparable to the process in adult women. Papers related to dementia or learning disability services were excluded for similar reasons. Finally, studies investigating antidepressant or psychotropic medication use in Pakistani women that did not contain an element on access to services were also excluded.

Study selection

A list of search terms was compiled by DK and JN, by drawing upon other systematic reviews in this area and the authors’ knowledge of previous research. Databases were searched for published journal articles, and a range of websites that indexed health and social care studies were searched to identify grey literature (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Sources used in the review

| Type of source | Databases |

|---|---|

| Electronic Databases (peer reviewed articles) |

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL Plus) EMBASE Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) MEDLINE PsycINFO Social Sciences Abstracts Social Sciences Citation Index Sociological Abstracts |

| Grey Literature |

OpenGrey Social Care Online Index to Theses Electronic Theses Online Services (ETHOS) The Health and Social Care Information Centre Website (HSCIC) Association of Health Observatories Website |

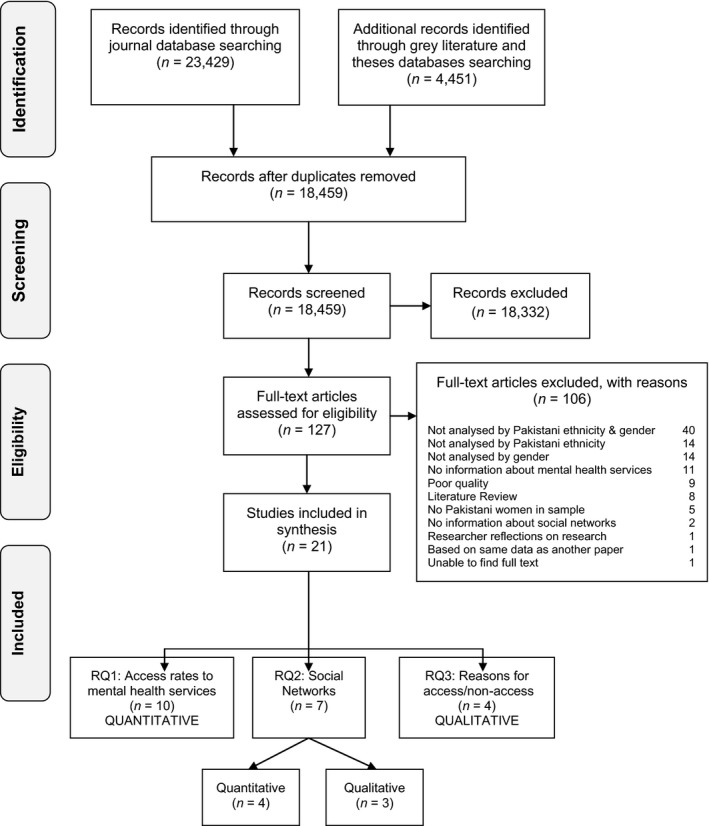

Initial searches were tested in Medline and revised (see Box 1). Searches were adapted for each database. The Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) and Association of Health Observatories websites were searched manually. Searches were undertaken in April 2014. The searches yielded 27,880 papers. Results were imported into EPPI‐Reviewer 4 (Thomas et al. 2010) and the duplicate process was carried out, leaving 18,459 documents. Screening was undertaken by DK, after which, the full texts of 127 papers were reviewed. A PRISMA (Moher et al. 2009) diagram of the screening and eligibility process is shown in Figure 1.

Box 1. Search terms for the review.

|

Mental Health OR mental illness OR health service* OR healthcare disparit* OR health disparit* OR health equit* OR health inequit* OR health equal* OR health inequal* OR Health Care Services* OR Health Care Utilization* OR psychiatr* OR Health Care Psychology* OR access* OR health access* OR healthcare access* OR care path* OR help seek* OR service barrier* OR barrier to service* OR social network OR family network OR Social Support OR family support OR network analysis OR support network OR social capital AND ethnic* OR south asia* OR asian* OR pakistan* OR rac* OR Muslim* OR bme* OR minorit* AND uk* OR united kingdom* OR britain* OR Great Britain OR England |

Figure 1.

The Review Process of inclusion and exclusion of studies using PRISMA reporting (Moher et al. 2009).

Critical appraisal

Each of the 127 papers was critically appraised by DK and HB. Disagreements on inclusion (n = 5/127), were resolved by JN. Different quality assessment tools were used for each methodologically distinct study: for quantitative papers, the Study Quality Tool (Zaza et al. 2000) was used; for qualitative papers, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist (CASP, 2014a); for mixed‐methods papers, the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Pluye et al. 2011) and for systematic reviews, the CASP Systematic Review Checklist (CASP, 2014b). These tools were used as guides to assess the quality of the studies on which judgements were made about their inclusion. Papers that were appraised as poor on research design, inappropriate in the choice of methods or lacking robust analysis were excluded. During critical appraisal, posters and conference paper abstracts were excluded, but where possible, published papers referring to presentations were sought out. It was not possible to find one thesis that explored the health needs of Asian women in Manchester, despite making enquiries with the awarding university and the author.

At this stage, 106 papers were excluded (see Figure 1) as they were irrelevant to the research questions. Most papers (64%) were excluded because they did not analyse data by Pakistani ethnicity, gender or both. Nine papers (8%) were excluded due to poor quality. Six papers that documented the results of the Count me in Censuses 2005 to 2010 were included, despite providing estimates of mental health inpatient use that included people who were under the age of 18. This was because those aged under 18 years only constituted between 1% and 2.9% of inpatients in the years 2005–2010. The remaining 21 papers were categorised according to which research questions they addressed. Papers were published between 1999 and 2013, except one (published in 1977). Ten of these related to research question 1 (comparison of rates of use of mental health service between Pakistani women and women from other ethnic groups) and were quantitative in nature. Seven papers were relevant to research question 2 (the nature of Pakistani women's social networks); three were qualitative and four quantitative. Data were synthesised separately for quantitative and qualitative studies and then compared and contrasted. Four studies related to the final research question (all qualitative).

Data extraction and synthesis

Due to the differing nature of types of evidence collated in the review, it was necessary to extract different types of data. For quantitative studies rates of access, odds ratios, relative risks or proportions were extracted, whereas for qualitative studies main themes and interviewee quotes were extracted. Information relating to study characteristics was extracted for all studies (geographical location, number of participants, number of Pakistani female participants, age range, aims of the study, the target sample and research method). For qualitative studies that had conducted research with people from a range of ethnic groups, data relating to Pakistani women were extracted if possible.

Results

How does the usage of mental health services for Pakistani women in the UK compare with women of other ethnic groups?

Ten quantitative papers provided data that were relevant to this research question. Seven related to usage rates of inpatient services. One provided access rates to outpatient services, one reported on consultations with doctors for stress‐related or emotional problems, and one provided both rates of access for outpatient services, and consultations with general practitioners (GPs) (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of studies providing data on rates of usage of mental health services (n = 10)

| Author (date) | Location | Sample size (age) | Pakistani women N (%) | Aims | Sample | Research method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Care Quality Commission & National Mental Health Development Unit (2011) | England and Wales | 32,799 (all ages) | 114 (0.3) | To obtain accurate figures relating to patients in mental health wards by ethnic group | Mental health unit inpatients and patients on Community Treatment Orders (CTOs) | Census |

| Care Quality Commission & National Mental Health Development Unit (2010) | England and Wales | 31,786 (all ages) | 110 (0.3) | To obtain accurate figures relating to patients in mental health wards by ethnic group | Mental health unit inpatients and patients on Community Treatment Orders (CTOs) | Census |

| Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (2008) | England and Wales | 31,020 (all ages) | 121 (0.3) | To obtain accurate figures relating to patients in mental health wards by ethnic group | Mental health unit inpatients | Census |

| Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (2007a) | England and Wales | 31,187 (all ages) | 85 (0.3) | To obtain accurate figures relating to patients in mental health wards by ethnic group | Mental health unit inpatients | Census |

| Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (2007b) | England and Wales | 32,023 (all ages) | 104 (0.3) | To obtain accurate figures relating to patients in mental health wards by ethnic group | Mental health unit inpatients | Census |

| Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (2005) | England and Wales | 33,785 (all ages) | 90 (0.3) | To obtain accurate figures relating to patients in mental health wards by ethnic group | Mental health unit inpatients | Census |

| Cochrane (1977) | England and Wales | N/Ra (15+) | N/Ra | To report admissions to mental hospitals in 1971, by country of birth | Admissions to mental health hospitals in 1971 | Survey |

| Glover and Evison (2009) | England | N/Ra (18–64) | N/Ra | To examine the extent to which IAPT services have been used for ethnic minority groups | Patients using Crisis Resolution Home Treatment, Early Intervention, Assertive Outreach and IAPT services | Survey |

| Lloyd and Fuller (2002) | England | 4281 (16–74) | 387 (8.0) | To investigate the differences in mental health service use between ethnic groups | Household residents (sampled from The Health Surveys for England 1998 and 1999) with ethnic minority boost sample | Survey |

| Bajekal (2001) | England | 16484 (16–74) | 1,028 (6.2) | To investigate the differences in health service use and prescribed medicines between ethnic groups | Household residents, with ethnic minority boost sample | Survey |

Not reported.

For the papers that were included, there were differences in the way that rates could be interpreted. The Count me in Censuses (which accounted for six of seven papers reporting on access to inpatient services) provided counts of people who were using mental health inpatient services on census day (31st March). This differed from the paper by Glover and Evison (2009), which provided data on access to mental health outpatient services over 12 months. Both used NHS administrative data. The community surveys [(Health Survey for England 1999 and Ethnic Minority Psychiatric Illness Rates in the Community (EMPIRIC)] provided figures for consultations with GPs for mental illness based on participant self‐report and related to the previous 6 (EMPIRIC) or 12 (HSE 1999) months.

Inpatient services

The Count Me In Census of inpatients in mental health units in 2009 and 2010 (Care Quality Commission & National Mental Health Development Unit, 2010, 2011), estimated that the age‐ and sex‐standardised rates for admission for Pakistani women (2009, standardised ratio [SR] = 65, confidence interval [CI] = 53–79; 2010, SR = 70, CI = 57–84) were less than for white British women (2009, SR = 94, CI = 93–96; 2010, SR = 95, CI = 93–96) and less than the average rates (100) for women. However, the results from the years 2005 to 2008 suggested that the rates of admission for Pakistani women were no different from the average. Cochrane's study (1977) showed lower rates of admission for Pakistani (defined as born in Pakistani) women (374 per 100,000 – the lowest admission rate out of any country of birth).

Outpatient services

Only two papers provided rates of usage of outpatient services. One was a nationally representative English community survey (Ethnic Minority Psychiatric Rates in the Community (EMPIRIC), Lloyd & Fuller 2002), which showed no differences in the percentages of Pakistani women and white women who had seen a Community Psychiatric Nurse (1%) in the preceding 6 months, nor in the percentages that had seen a counsellor or psychologist within the same timeframe (2% for Pakistani women vs. 3% for white women).

The other paper (Glover & Evison 2009) provided rates of access to the following NHS services: Crisis Resolution Home Treatment (CRHT), Early Intervention (EI), Assertive Outreach (AO), and Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) Services. The rates were provided for those aged 18–64 years, and used 2007 Office of National Statistics (ONS) Mid‐Year Estimates to standardise for age, although data were collected between March 2008 and March 2009. Compared with white British women's use of CRHT services (89.2/100,000, CI = 87.6–90.9), Pakistani women had lower rates of use (66.5/100,000, CI = 57.2–77.0). AO rates were similar for Pakistani (29.8/100 K, CI = 23.6–37.0) and white British women (36.5/100 K, CI = 35.5–37.6). However, Pakistani women had higher usage of EI services (109.5/100 K CI = 95.2–125.3) compared to white British women (76.4/100 K CI = 74.2–78.8). Pakistani women were less likely to be referred to IAPT services (212.7/100K, CI 161.5–275) compared with white British women (457/100K, CI = 444.8–469.5), and to receive treatment from IAPT services (165/100K, CI = 120.4–220.8 vs. 296.7/100K, CI = 286.9–306.8 for white British women). The authors also calculated the expected rates of referral and entry given the rates of psychiatric illness from the EMPIRIC survey (Sproston & Nazroo 2002) and concluded that referral and entry rates to treatment for Pakistani women were less than would be expected from the prevalence rates for common mental disorder.

Consultation of GP for mental illness

According to the estimates from EMPIRIC (Lloyd & Fuller 2002), Pakistani women were less likely to have consulted a doctor for emotional or stress‐related problems (relative risk [RR] = 0.60, SE = 0.16) compared to white women (RR = 1). However, the Health Survey for England 1999 (Bajekal 2001) concluded that when compared with women on average, there was no difference between the rates of Pakistani (standardised ratio [SR] = 1.21, SE = 0.11) and white women (SR = 1) who consulted the GP for being anxious or depressed. The opposite direction of effects in these two studies could be explained by the question wording. The EMPIRIC question asked whether the last visit to the doctor was for a ‘stress‐related or emotional problem’ (Sproston & Nazroo 2002, p. 182), whereas the HSE 1999 asked about service use over the last 12 months. Therefore, Pakistani women were less likely to have most recently visited the GP about a mental illness, but over the last 12 months, there was no difference in their consultation rates compared to white women.

All of the papers that addressed this research question, with one exception (Glover & Evison 2009), did not adjust mental health service usage rates for the level of mental illness (nor for socioeconomic factors). These omissions mean that the ethnic differences in mental health service use may have been underestimated, especially since the rates of mental illness are higher for Pakistani women (Weich & McManus 2002) and they are more likely to live in poverty (Nandi & Platt 2010).

What is the nature of Pakistani women's social networks and how does this compare with women from other ethnic groups?

The quantitative papers were comparative in nature, investigating social support and social involvement in relation to women of other ethnic groups. Three of the qualitative papers focussed on Pakistani participants only, and one sought the views of older people from ethnic minority groups (Table 3). Papers focussed on contact with family and friends (which gives an indication of network content), and social support (network function).

Table 3.

Summary of studies relating to social networks of Pakistani women (n = 7)

| Author (date) | Location | Sample size (age) | Pakistani women N (%) | Aims | Sample | Research method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Platt (2009) | England and Wales | 10,028 (16–65) | 414 (4.1) | To explore the extent to which social activity in England and Wales varies by ethnic group and whether risks of social isolation are higher for some groups than others | Household residents, with ethnic minority boost sample | Survey |

| Natarajan (2006) | England | 10,114 (16+) | 795 (7.9) | To explore the differences in general health, acute sickness, long‐standing illness, psychosocial measures (GHQ12 and perceived social support) and prescribed medicines by ethnicity | Household residents, with ethnic minority boost sample | Survey |

| Stansfeld and Sproston (2002) | England | 4,281 (16–74) | 387 (8.0) | To examine the levels of support across different ethnic groups and to investigate whether this contributes to differences in psychiatric morbidity | Household residents (sampled from The Health Surveys for England 1998 and 1999) with ethnic minority boost sample | Survey |

| Calderwood and Tait (2001) | England | 16,484 (16–74) | 1028 (6.2) | To explore the differences in self‐reported long‐standing illness and acute sickness, self‐assessed general health and two measures of psychosocial health, the GHQ12 and perceived social support | Household residents, with ethnic minority boost sample | Survey |

| Gask et al. (2011) | East Lancashire | 15 (23–73) | 15 (100) | To examine the processes involved in why and how British Pakistani women fail to recover from depression and remain persistently low in mood | Pakistani women living in the local area with a diagnosis of depression from their GP | Qualitative interview |

| Rodriguez (2007) | North London | 10 (40–59) | 10 (100) | To address the issue of migration as a factor of change in the gendered division between private and public spaces | Pakistani women living in the local area, originating from Punjab or Sindh metropoles of Pakistan, with secondary school education or higher | Qualitative interview |

| Campbell and McLean (2003) | South England | 26 (15–66) | 13 (50.0) | To examine potential obstacles for Pakistani people in England to participate in local initiatives to reduce health inequalities | Pakistani Kashmiri residents in the local area | Qualitative interview |

Network content

Pakistani women's social networks consisted mainly of relatives and other Pakistani people. Stansfeld and Sproston (2002) found that Pakistani women were the most likely (out of all ethnic groups: white, Irish, black Caribbean, Indian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani) to have seen relatives in the past month [ratio of means (RoM) = 1.33, SE = 0.12], but they were the least likely to have seen friends in the past month (RoM = 0.46, SE = 0.07). Campbell and McLean's (2003) study found that participants preferred to make friends with other Pakistani or South Asian people. However, the extent to which this was a choice for women appeared to be constrained by two factors: first several of the Pakistani‐born women in the sample ‘lived in households in which women did not leave the home unaccompanied’ and, second, women who had poor English language skills ‘were limited in their interaction with non‐Pakistani people’ (Campbell & McLean 2003, p. 14).

A strong sense of social isolation emerged as a core theme in some papers. Gask et al. (2011) found that social isolation was a feature of the experiences of Pakistani depressed women. This was perhaps to be expected given the nature of the sample, but it was also a feature of Pakistani women's networks in non‐clinical samples. Platt (2009) using the data from the 2001 Citizenship Survey, found that 17% of Pakistani women (the highest of any ethnic group: white British, black Caribbean, black African, Indian, Bangladeshi and Pakistani) were classified as socially isolated (defined as receiving or making infrequent visits, going out infrequently and low contact with clubs and organisations).

Participants in Campbell and McLean's (2003) study spoke of how involvement in community organisations was seen as a ‘white thing’ and if they participated in such groups, they might be accused of ‘acting white’ (p. 17) by people from their own ethnic group. Pakistani‐born women were often ‘isolated from mainstream English life’ (2003, p. 14) and while they were aware of the existence of women's groups and English classes, they rarely attended them. This was in contrast to younger England‐born Pakistani women who were more likely to be involved in community groups. Rodriguez (2007) reported that Pakistani women attended community centres and had built ‘social women‐centred (sic) networks’ (2007, p. 106). However, this study consisted of Pakistani women born in the Punjab or Sindh metropolitan areas, with high levels of education sampled in ‘mixed British and immigrant neighbourhoods’ (2007, p. 98), compared to the Pakistani Kashmiri women sampled by Campbell and McLean (2003) who were living in deprived (in the lowest quintile), multi‐ethnic neighbourhoods (at least 30% Pakistani), which may account for the difference in these findings.

Network function

The Health Survey for England (HSE) 1999 (Calderwood & Tait, 2001) found that 27% of Pakistani women perceived a severe lack of social support compared to 11% in the general population [odds ratio (OR) = 2.28, SE = 0.23]. Similar results were reported in Natarajan's paper (2006) using the HSE 2004 (Sproston & Mindell, 2006) where 30% of Pakistani women perceived a severe lack of social support compared to 11% in the general population (OR = 2.47, SE = 0.33).

Stansfeld and Sproston's paper (2002) found that Pakistani women reported high negative aspects of support (RR = 1.35, SE = 0.11) compared to white women (RR = 1). However, there were no differences in the perceived levels of low emotional and confiding support between Pakistani women (RR = 0.95, SE = 0.13) and white women (RR = 1). This could have been a result of the way emotional support was measured; it only related to the support received from a nominated closest person, whereas in the HSEs 1999 and 2004 social support related to all family and friends.

One study highlighted the importance of the (extended) family as a source of support, advice and care, and in some cases family were the only source of support available to Pakistani women, especially those who were born in Pakistan (Campbell & McLean 2003).

What are the reasons for the mental health service utilisation patterns of Pakistani women? Are social networks implicated?

All the papers for this research question were qualitative in nature (Table 4). It was not the aim of any of the studies to investigate the association between social networks and usage of mental health services. However, there were indications that social networks in the form of family and close relatives could influence decisions to seek mental healthcare.

Table 4.

Summary of studies relating to reasons for patterns of usage of mental health services (n = 4)

| Author (date) | Location | Sample size (age) | Pakistani women N (%) | Aims | Sample | Research method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wood (2011) | Leeds | 5 (20–29) | 4 (80.0) | To investigate how South Asian women understand and make sense of their experiences of self harm, and how they perceive support services | South Asian women aged between 18 and 40 with experience of self‐harm, educated in Britain in the local area | Qualitative interview |

| Chew‐Graham et al. (2002) | Salford and Trafford, Manchester | 29 (17–50) | 18 (62.1) | To investigate the self‐reported needs of South Asian women suffering mental illness which may lead to suicide and self‐harm | Attenders of existing South Asian Women's groups in the local area | Focus groups |

| Grewal and Lloyd (2002) | England | 116 (25–50) | 11 (9.5) | To examine respondents’ accounts of their pathways to mental health services | Purposive sample from EMPIRIC respondents | Qualitative interview |

| Cinnirella and Loewenthal (1999) | South East England, London and Midlands | 52 (N/Ra) | 13 (25.0) | To investigate the degree to which beliefs about religion intertwine with lay beliefs about depression and schizophrenia | Pakistani Muslim, white Catholic, black African and Afro‐Caribbean Christian and white Orthodox Jewish women living in the specified local areas | Qualitative interview |

Not reported.

Coping alone as a result of the stigma of mental illness

All papers found that women felt they had to cope alone with mental illness. In three of four papers, one of the reasons for this was the stigma associated with having and speaking about mental illness, and this was argued to be directly linked to Pakistani culture: family and community members were seen as sources of stigmatising attitudes. The findings indicated that keeping problems to one's self was often a coerced choice, and one paper (Cinnirella & Loewenthal 1999) found that there were strong beliefs among participants that problems should be kept private within the family. The fear of being gossiped about was a strong theme in the focus groups conducted by Chew‐Graham et al. (2002) and the way in which this could ruin one's reputation was commented on by Cinnirella and Loewenthal (1999). None of the papers were comparative in nature, therefore the levels of stigma for Pakistani women could not be compared with women from other ethnic groups.

Preference for, but problems with, Pakistani health professionals

There was a clear contradiction evident in three of the four papers: Pakistani women preferred to see someone of their own ethnic group so that their problems could be understood appropriately; all of the women that took part in interviews in Cinnirella and Loewenthal's paper (1999) stated that they would prefer to see a Pakistani Muslim professional. However, women were also mistrustful of consulting health professionals from their own community due to fear of disclosure to family members and other people in the community. Only one paper found that the reason for wanting to see a professional of the same background was due to ‘mainstream service providers [who] were usually white’ (Chew‐Graham et al. 2002, p. 344) potentially having fixed views about the Pakistani community and displaying racism.

Language barriers

Two papers found that lack of English language skills affected access to, or experience of, services (Chew‐Graham et al. 2002, Grewal & Lloyd 2002). In particular, there was a sense that lack of English could impact negatively on knowledge of available services (Chew‐Graham et al. 2002) and on the quality of services received, if they were provided via an interpreter, as patients could not communicate directly with health professionals (Grewal & Lloyd 2002). Only one paper made reference to the lack of knowledge about mental health services among Pakistani women (Grewal & Lloyd 2002).

Discussion

The review set out to answer whether the usage of mental health services differed between Pakistani women and women of other ethnic groups in the UK, the nature of Pakistani women's networks compared with women of other ethnic groups, and whether social networks were involved in seeking help for mental illness.

Pakistani women are less likely to use specialist mental health services

The review provided evidence that rates of access to inpatient service are lower for Pakistani women than for white British women. Unfortunately, many of the studies did not take into account the level of mental illness nor did they adjust rates for important socioeconomic factors which are likely to impact on the access that people have to services (Goddard & Smith, 2001). Rates were adjusted for mental illness in relation to outpatient services in Glover and Evison's report (2009) and the authors suggest that rates of access to services were lower than would be expected for IAPT services. Rates of access to Early Intervention services for Pakistani women were higher than for white British women perhaps reflecting slightly higher rates of psychosis in older Pakistani women aged 55–74 years (Weich et al. 2004). Pakistani women's GP consultation rates for mental illness were about the same as for white women, which is surprising given that Pakistani women have higher GP consultation rates than most other ethnic groups (Nazroo et al. 2009).

Current UK mental health policy does not aim to directly tackle these ethnic inequalities in use of mental health services, although ‘under‐representation of Asian women receiving support from mental health services’ (Her Majesty's Government and Department of Health 2011, p. 26) has been highlighted as a reason for disaggregating outcome indicators provided by NHS England. Unfortunately, this has not happened; the latest figures for 2013/2014 are disaggregated by ethnicity (with Pakistani as a separate ethnic group), but not by gender (Community and Mental Health Team: Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2013b). NHS England have attempted to provide access rates to IAPT by ethnic group (Community and Mental Health team: Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2014b) and gender, but again this fell short of what was required, as figures were not age standardised nor adjusted for levels of mental illness. Further, ethnic group was not recorded for 28.5% of women.

Pakistani women have high levels of social isolation

In comparison to other women, Pakistani women's networks were more likely to consist of a high number of relatives rather than friends. Pakistani women also had limited social interaction with people who were not Pakistani and those who were not part of their family or community. They exhibited low involvement in community organisations and clubs. Pakistani women's networks showed high levels of lack of social support and high negative aspects of networks compared to white British women.

Only one study (Campbell & McLean 2003) differentiated between women born in Pakistan and those born in England and how this might affect the nature of their social networks. They found that Pakistani‐born women's networks contained less interaction with people whose ethnicity was not Pakistani.

Stigma towards mental illness and services within social networks

The studies reviewed showed that Pakistani women felt they had to cope alone with mental illness. There was an indication that social networks influenced attitudes towards mental health services and the course of action that Pakistani women chose to take. These negative attitudes about having mental illness were also evident in wider community networks. However, there were not any studies that provided information about the exact elements (e.g. spouse, wider family, friends) of social networks that displayed negative views about mental illness and mental health services. Previous studies in the United States suggest that increased contact with relatives can decrease mental health service use (Sherbourne 1988, Maulik et al. 2009), and increased support from friends has the potential to increase usage of mental health services (Vera et al. 1998). Hence, the type of contacts that are available in support networks can differentially influence usage of mental health services. This could be related to family members being more likely to feel the effects of stigmatising attitudes towards having a family member with mental illness; these effects may be felt less by friends.

One deterrent to accessing services was the fear that professionals of the same ethnic group would leak information to people that women knew. This was related to the stigma associated with having and talking about a mental illness. This is not something which is specific to Pakistani women. Rather it is a common feature among people suffering from mental distress (Thornicroft 2006), but there is the possibility that the level of stigma felt by Pakistani women may act as a greater deterrent to accessing services than for women from other ethnic groups. However, the levels of stigma by ethnicity could not be investigated in the review, because none of the papers commenting on stigma were comparative in nature. There are not any large survey data sets in the UK that have collected levels of felt stigma between ethnic groups, and it did not form a substantial part of the research programme undertaken by Time to Change England (cf. (Corker et al. 2013). However, there is evidence from other countries that for some ethnic minority groups, the stigma surrounding mental health‐related problems might be a greater deterrent to seeking help than for white majority populations (Pescosolido et al. 2013, Clement et al. 2015).

Inadequacy of NHS services for Pakistani women

It was evident that some Pakistani women have language difficulties which impede their abilities to gain access to services, and can also have a negative effect on the experience of services. Only one study linked women's lack of willingness to access services due to racism from white health professionals. This may have been because none of the research studies were designed to specifically ask about racism with reference to health services. There were no studies looking at access to mental health services in the voluntary sector; given the results of the review that Pakistani women are overall less likely to access NHS mental health services, it is possible that the voluntary sector is a more likely route for gaining access to services.

Strengths and limitations of the review

This is the first review to the authors’ knowledge that has been conducted on this ethnic group in the UK. Due to the very specific nature of the research questions, we were able to provide coherent answers in relation to Pakistani women in the UK. The findings of the results relating to mental health service usage and the quantitative studies about social support are generalisable to the population of England (or UK). The evidence obtained from the synthesis of the qualitative studies may not be generalisable to the wider population, but it is encouraging that many similar themes were extracted from these studies. In particular, there were very few Pakistani women (between 4 and 18) in the research studies that answered the third research question (whether social networks were involved the help‐seeking and access process for Pakistani women). Hence, the results for this research question are limited and should be viewed with caution. This also highlights the lack of studies in the UK that have sought to determine the influence of social networks on mental health service use, for both Pakistani women, and for women more generally. In addition, the use of the category ‘Pakistani’ is not without problems; the term must not be assumed to represent a homogenous group of women with identical backgrounds and experiences. However, the current ethnic categories that are used in research studies and national statistics are the only ones available for highlighting ethnic inequalities.

Many of the identified papers were excluded from the review due to their inapplicability to the research questions and a relatively small number (n = 9) were excluded due to methodological limitations at the critical appraisal stage. This is perhaps in contrast to other systematic reviews that excluded large numbers of papers due to poor quality (Morgan et al. 2013). This reflects the narrow nature of the topic and the lack of appropriate use of ethnic categories in previous research. Indeed a large number (n = 54) of studies were excluded because they did not analyse Pakistani women as a unique category, but chose to subsume Pakistani women into the broader category of South Asian women.

Conclusions

Pakistani women are at a considerable disadvantage in gaining access to and using statutory mental health services, compared with white women. The review shows the importance of analysing Pakistani women separately from Indian and Bangladeshi women: future research and Department of Health published figures, should report and analyse Pakistani women as a separate group in order to provide accurate information on usage of mental health services. Current figures provided by the Department of Health via NHS England are not sufficient to monitor the differences in usage of mental health services between women of different ethnic groups, thereby preventing researchers to determine the equality or otherwise of usage of mental health services, on the grounds of ethnicity. Further, the review showed that Pakistani women tend to be socially isolated and have networks which display high levels of stigma towards mental illness and usage of mental health services. However, the review did not find any studies looking at the levels of stigma of mental illness between ethnic groups. Understanding Society, the UK's largest household longitudinal survey with an ethnic minority boost sample, is one survey that could be targeted by interested researchers, for inclusion of a survey module on mental health stigma, in order to establish if there are ethnic differences in mental illness stigma.

Conflict of interests statement

All authors declare that they have no conflicts of interests.

Acknowledgements

DK was supported by a PhD studentship from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC, grant number ES/J500094/1). JN was supported by the ESRC research grant Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (grant number ES/K002198/1). An earlier version of this paper was presented as a poster, at the British Sociological Association Medical Sociology Conference, in September 2013, and was made available by Medical Sociology Online (http://www.medicalsociologyonline.org/msoposters/medsoc2013.html).

References

- Bajekal M. (2001) Use of health services and prescribed medicines In: Erens B., Primatesta P. & Prior G. (Eds) Health Survey for England – The Health of Minority Ethnic Groups ‘99: Volume 1 Findings. The Stationery Office, London: Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140131031506/http://www.archive.official-documents.co.uk/document/doh/survey99/hse99-11.htm [Google Scholar]

- Bowl R. (2007) The need for change in UK mental health services: South Asian service users’ views. Ethnicity & Health 12 (1), 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burman E., Chantler K. & Batsleer J. (2002) Service responses to South Asian women who attempt suicide or self‐harm: challenges for service commissioning and delivery. Critical Social Policy 22, 641–668. [Google Scholar]

- Calderwood L. & Tait C. (2001) Self‐reported health and psychosocial well‐being In Erens B., Primatesta P. & Prior G. (Eds.), Health Survey for England – The Health of Minority Ethnic Groups ’99: Volume 1 Findings. The Stationery Office, London: Available at: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20140131031506/ http://www.archive.official-documents.co.uk/document/doh/survey99/hse99-02.htm [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C. & McLean C. (2003) Social capital, local community participation and the construction of Pakistani identities in England: implications for health inequalities policies. Journal of Health Psychology 8 (2), 247–262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission & National Mental Health Development Unit (2010) Count Me In 2009: Results of the 2009 National Census of Inpatients and Patients On Supervised Community Treatment in Mental Health and Learning Disability Services in England and Wales. Care Quality Commission, London. [Google Scholar]

- Care Quality Commission & National Mental Health Development Unit (2011) Count Me in 2010: Results of the 2010 National Census of Inpatients and Patients On Supervised Community Treatment in Mental Health and Learning Disability Services in England and Wales. Care Quality Commission, London. [Google Scholar]

- CASP (2014a) CASP Qualitative Checklist. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Oxford: Available at: http://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8 (accessed on 26/8/2014). [Google Scholar]

- CASP (2014b) CASP Systematic Review Checklist. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Oxford: Available at: http://www.casp-uk.net/#!casp-tools-checklists/c18f8 (accessed on 26/8/2014). [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry N., Husain N., Tomenson B. & Creed F. (2012) A prospective study of social difficulties, acculturation and persistent depression in Pakistani women living in the UK. Psychological Medicine 42 (06), 1217–1226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew‐Graham C., Bashir C., Chantler K., Burman E. & Batsleer J. (2002) South Asian women, psychological distress and self‐harm: lessons for primary care trusts. Health & Social Care in the Community 10 (5), 339–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cinnirella M. & Loewenthal K.M. (1999) Religious and ethnic group influences on beliefs about mental illness: a qualitative interview study. The British Journal of Medical Psychology 72, 505–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S., Schauman O., Graham T., et al. (2015) What is the impact of mental health‐related stigma on help‐seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychological Medicine 45 (1), 11–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochrane R. (1977) Mental illness in immigrants to England and Wales: an analysis of mental hospital admissions, 1971. Social Psychiatry 12, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (2005) Count Me In: Results of a National Census of Inpatients in Mental Health Hospitals and Facilities in England and Wales. Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, London. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (2007a) Count Me In 2007: Results of the 2007 National Census of Inpatients in Mental Health and Learning Disability Services in England and Wales. Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, London. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (2007b) Count Me In: Results of the 2006 National Census of Inpatients in Mental Health and Learning Disability Services in England and Wales. Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, London. [Google Scholar]

- Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection (2008) Count Me In 2008: Results of the 2008 National Census of Inpatients in Mental Health and Learning Disability Services in England and Wales. Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection, London. [Google Scholar]

- Community and Mental Health Team: Health and Social Care Information Centre (2014a) Mental Health Bulletin: Annual Report from MHMDS Returns – England 2013/2014. Health and Social Care Information Centre, Leeds. [Google Scholar]

- Community and Mental Health Team: Health and Social Care Information Centre (2013b) Mental Health Bulletin: Annual Report from MHMDS Returns – England 2011–2012, Initial National Figures. Health and Social Care Information Centre, Leeds. [Google Scholar]

- Community and Mental Health team: Health and Social Care Information Centre (2014b) Psychological Therapies, England: Annual Report on the Use of Improving Access to Psychological Therapies Services – 2012/2013. Experimental Statistics, Leeds. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper J., Murphy E., Webb R., Hawton K., Bergen H., Waters K. & Kapur N. (2010) Ethnic differences in self‐harm, rates, characteristics and service provision: three‐city cohort study. The British Journal of Psychiatry 197 (3), 212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper C., Spiers N., Livingston G. et al (2013) Ethnic inequalities in the use of health services for common mental disorders in England. Social Psychiatry & Psychiatric Epidemiology 48 (5), 685–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corker E., Hamilton S., Henderson C. et al (2013) Experiences of discrimination among people using mental health services in England 2008‐2011. The British Journal of Psychiatry 55, s58–s63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health (2005) Delivering Race Equality in Mental Health Care: An Action Plan for Reform Inside and Outside Services. Department of Health, London. [Google Scholar]

- Dixon‐Woods M., Kirk D., Agarwal S. et al (2005) Vulnerable Groups and Access to Health Care: A Critical Interpretive Review. National Coordinating Centre for Service Delivery and Organisation (NCCSDO), London. [Google Scholar]

- Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co‐ordinating Centre (EPPI‐Centre) (2010) EPPI‐Centre Methods for Conducting Systematic Reviews. Institute of Education, London. [Google Scholar]

- Garrett C.R., Gask L.L., Hays R. et al (2012) Accessing primary health care: a meta‐ethnography of the experiences of British South Asian patients with diabetes, coronary heart disease or a mental health problem. Chronic Illness 8 (2), 135–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gask L., Aseem S., Waquas A. & Waheed W. (2011) Isolation, feeling “stuck” and loss of control: understanding persistence of depression in British Pakistani women. Journal of Affective Disorders 128 (1–2), 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gater R., Tomenson B., Percival C. et al (2009) Persistent depressive disorders and social stress in people of Pakistani origin and white Europeans in UK. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 44 (3), 198–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P., Gilbert J. & Sanghera J. (2004) A focus group exploration of the impact of izzat, shame, subordination and entrapment on mental health and service use in South Asian women living in Derby. Mental Health, Religion & Culture 7 (2), 109–130. [Google Scholar]

- Goddard M. & Smith P. (2001) Equity of access to health care services: theory and evidence from the UK. Social Science & Medicine 53 (9), 1149–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover G. & Evison F. (2009) Use of New Mental Health Services by Ethnic Minorities in England. North East Public Health Observatory (NEPHO), Durham. [Google Scholar]

- Gourash N. (1978) Help‐seeking: a review of the literature. American Journal of Community Psychology 6 (5), 413–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal I. & Lloyd K. (2002) Use of services In: O'Connor W. & Nazroo J. (Eds) Ethnic Differences in the Context and Experience of Psychiatric Illness: A Qualitative Study, pp. 51–60. The Stationery Office, London. [Google Scholar]

- Her Majesty's Government, & Department of Health (2011) No Health without Mental Health: A Cross‐Government Mental Health Outcomes Strategy for People of All Ages. Department of Health, London. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb J., Bower P., Rogers A., Dowrick C. & Gask L. (2012) Access to mental health in primary care: a qualitative meta‐synthesis of evidence from the experience of people from “hard to reach” groups. Health 16 (1), 76–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd K. & Fuller E. (2002) Use of services In: Sproston K. & Nazroo J. (Eds) Ethnic Minority Psychiatric Illness Rates in the Community (EMPIRIC): Quantitative Report, pp. 101–115. The Stationery Office, London. [Google Scholar]

- Maulik P.K., Eaton W.W. & Bradshaw C.P. (2009) The role of social network and support in mental health service use: findings from the Baltimore ECA study. Psychiatric Services 60 (9), 1222–1229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G. & The PRISMA Group (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine 6 (7), e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M., Kenten C., Deedat S. & On Behalf Of The Donate Programme Team (2013) Attitudes to deceased organ donation and registration as a donor among minority ethnic groups in North America and the UK: a synthesis of quantitative and qualitative research. Ethnicity & Health 18 (4), 367–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandi A. & Platt L. (2010) Ethnic Minority Women's Poverty and Economic Well Being. Government Equalities Office, London. [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan L. (2006) Self‐reported health and psychosocial well‐being In Sproston K. & Mindell J. (Eds.), Health Survey for England 2004. Volume 1: The Health of Minority Ethnic Groups, pp. 25–61. The Information Centre, Leeds: [Google Scholar]

- Nazroo J. (2001) Ethnicity, Class and Health. Policy Studies Institute, London. [Google Scholar]

- Nazroo J., Falaschetti E., Pierce M. & Primatesta P. (2009) Ethnic inequalities in access to and outcomes of healthcare: analysis of the Health Survey for England. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 63 (12), 1022–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido B.A. (1992) Beyond rational choice: the social dynamics of how people seek help. American Journal of Sociology 97 (4), 1096–1138. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido B.A. (2011) Social network influence in mental health and illness, service use and settings and treatment outcomes In: Pilgrim D., Rogers A. & Pescosolido B.A. (Eds) The Sage Handbook of Mental Health and Illness, pp. 512–536. Sage Publications Ltd, London. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido B.A., Wright E.R., Alegría M. & Vera M. (1998) Social networks and patterns of use among the poor with social networks mental health problems in Puerto Rico. Medical Care 36 (7), 1057–1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido B.A., Medina T.R., Martin J.K. & Long J.S. (2013) The “backbone” of stigma: identifying the global core of public prejudice associated with mental illness. American Journal of Public Health 103 (5), 853–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platt L. (2009) Social activity, social isolation and ethnicity. The Sociological Review 57 (4), 670–702. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez A. (2007) Migration and increased participation in public life: the case of Pakistani women in London. Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 28 (3), 94–112. [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne C.D. (1988) The role of social support and life stress events in use of mental health services. Social Science & Medicine 27 (12), 1393–1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sproston K. & Nazroo J. (2002) Ethnic Minority Psychiatric Illness Rates in the Community (EMPIRIC). The Stationery Office, London. [Google Scholar]

- Sproston K. & Mindell J. (2006) Health Survey for England 2004: The Health of Minority Ethnic Groups (Vol. 1). The Information Centre, Leeds. [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld S.A. & Sproston K. (2002) Social support and networks InSproston K. & Nazroo J. Y. (Eds), Ethnic Minority Psychiatric Illness Rates in the Community (EMPIRIC): Quantitative Report, pp. 117–134. The Stationery Office, London. [Google Scholar]

- Ten Have M., Vollebergh W., Bijl R. & Ormel J. (2002) Combined effect of mental disorder and low social support on care service use for mental health problems in the Dutch general population. Psychological Medicine 32 (02), 311–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J., Brunton J. & Graziosi S. (2010) EPPI‐Reviewer 4: Software for Research Synthesis. EPPI‐Centre Software. Social Science Research Institute, Institute of Education, London. [Google Scholar]

- Thornicroft G. (2006) Shunned: Discrimination Against People with Mental Illness. Oxford University Press, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Vera M., Alegría M., Freeman D.H., Robles R., Pescosolido B. & Peña M. (1998) Help seeking for mental health care among poor Puerto Ricans: problem recognition, service use, and type of provider. Medical Care 36 (7), 1047–1056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weich S. & McManus S. (2002) Common mental disorders In: Sproston K. & Nazroo J.Y. (Eds) Ethnic Minority Psychiatric Illness Rates in the Community (EMPIRIC): Quantitative Report, pp. 25–46. The Stationery Office, London. [Google Scholar]

- Weich S., Nazroo J., Sproston K. et al (2004) Common mental disorders and ethnicity in England: the EMPIRIC study. Psychological Medicine 34 (8), 1543–1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood S. (2011) Exploring Experiences and Meanings of Self Harm in South Asian Women in the UK. The University of Leeds, Leeds, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Zaza S., Wright‐de Aguero L.K., Briss P.A. et al (2000) Data collection instrument and procedure for systematic reviews in the guide to community preventive services. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 18 (99), 44–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]