Abstract

Objective

Despite long‐standing safe and effective use of immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IgRT) in primary immunodeficiency, clinical data on IgRT in patients with secondary immunodeficiency (SID) due to B‐cell lymphoproliferative diseases are limited. Here, we examine the correlation between approved IgRT indications, treatment recommendations, and clinical practice in SID.

Methods

An international online survey of 230 physicians responsible for the diagnosis of SID and the prescription of IgRT in patients with hematological malignancies was conducted.

Results

Serum immunoglobulin was measured in 83% of patients with multiple myeloma, 76% with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and 69% with non‐Hodgkin lymphoma. Most physicians (85%) prescribed IgRT after ≥2 severe infections. In Italy, Germany, Spain, and the United States, immunoglobulin use was above average in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia, while in the UK considerably fewer patients received IgRT. The use of subcutaneous immunoglobulin was highest in France (34%) and lowest in Spain (19%). Immunologists measured specific antibody responses, performed test immunization, implemented IgRT, and used subcutaneous immunoglobulin more frequently than physicians overall.

Conclusions

The management of SID in hematological malignancies varied regionally. Clinical practice did not reflect treatment guidelines, highlighting the need for robust clinical studies on IgRT in this population and harmonization between countries and disciplines.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukemia, hematological disorders, immunoglobulins, infection, international survey, IVIG, multiple myeloma, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma, SCIG, secondary immunodeficiency

1. INTRODUCTION

Hypogammaglobulinemia is characterized by a decrease in functional or total serum immunoglobulin (Ig) levels and can lead to immunodeficiency associated with recurrent and severe infections. Primary immunodeficiency (PID) is caused by hereditary and genetic factors, while secondary immunodeficiency (SID) is mainly a consequence of a variety of diseases or a side effect of a range of medical treatments.1 Patients with B‐cell lymphoproliferative diseases are particularly prone to SID due to immunodeficiency caused by the underlying malignancies or the chemoimmunotherapies used to treat the malignancies. Standard treatment protocols of NHL, MM, and CLL include conventional chemotherapeutics such as cyclophosphamide. The spectrum of treatments is entity‐dependent and extended by targeted therapies, which are associated with specific immune defects and dysregulations. Anti‐CD20 antibodies, inducing long‐lasting B‐cell deficiency are applied in B‐cell NHL and CLL, whereas proteasome inhibitors (eg, bortezomib) and immunomodulators (eg, lenalidomide) are standard treatments for myeloma patients.2 More recent targeted therapies, such as Bruton's tyrosine kinase and Phosphoinositide 3‐kinase δ inhibitors, are broadly applied in CLL and certain NHL subtypes. The increased use of novel B‐cell targeted therapies, targeting differentiation, function and apoptosis of B cells, and CD19‐targeted chimeric antigen receptor T cells (CAR T) as well as the consequent increased survival rates in lymphoproliferative diseases have led to an increased diversity and incidence of SID in hematological malignancies.3 In chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), up to 85% of patients develop hypogammaglobulinemia and infections are the major cause of morbidity and mortality, contributing to 25%‐50% of deaths.4, 5, 6, 7 Similarly, life‐threatening infections are a major cause of morbidity and mortality in multiple myeloma (MM), with 30% being fatal, and have increased since the introduction of novel therapies.8, 9, 10

Treatment of immunodeficiency by immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IgRT) is well established in PID due to proven efficacy and safety.11 In SID, despite being more prevalent than PID, clinical data on IgRT are limited. Evidence for the use of IgRT in CLL and MM is predominantly based on clinical trials performed 20‐30 years ago, before modern immunosuppressive therapies were introduced.10, 12, 13, 14 A meta‐analysis of randomized trials in patients with CLL and MM reported that prophylactic IgRT significantly reduced major and clinically documented infections, but did not improve survival.15

Immunoglobulin replacement therapy may be administered intravenously (IV) or subcutaneously (SC). In PID, both routes of administration have been shown to be effective and safe. European consensus proposals recommend that patients with PID should be given the choice between IVIG and SCIG.16, 17 In SID, the safety and efficacy of SCIG has been demonstrated in case series in patients with lymphoproliferative diseases and hypogammaglobulinemia.12, 18 SCIG might have several advantages over IVIG to some patients. SCIG does not require venous access and allows more flexible and convenient self‐administration at home than IVIG.12 SCIG has been associated with an improvement in perceived health‐related quality of life.12, 19 Additionally, pharmacokinetics may be preferable, as SCIG treatment leads to higher and more stable IgG trough levels, providing patients with a more consistent protection against infections.1, 20 The use of SCIG varies greatly between countries. For example, in Scandinavia, SCIG is used in 80%‐90% of PID patients, while in Spain, France, and Italy IVIG is used predominantly.21

In the United States and Europe, national recommendations regarding the use of IgRT in hypogammaglobulinemia associated with hematological malignancies extend to conditions beyond those included in the marketing authorizations, although the recommendations are often not based on strong evidence and vary widely.11 In addition to promoting off‐label use, differences in current recommendations highlight open questions regarding the selection of patients who might benefit from IgRT, such as Ig and Ig subclass serum levels, testing specific antibody responses, test immunization, and infection history. In a 2014 European consensus statement, the determination of serum Ig concentrations and the levels of specific serum antibody titers in response to vaccination was agreed as a useful approach for patient selection in SID, although the need for more research was acknowledged.17

Additional open questions include Ig dose, the monitoring of Ig trough levels during therapy, and criteria for the duration of treatment. There is no consensus on the duration of IgRT. Re‐evaluation of the effectiveness of IgRT after a period of time, 6 months to a year, has been suggested by some experts.7, 22 Agostini et al11 recommended that treatment discontinuation may be considered in patients with a stable primary condition who have received IgRT for more than a year and who have not reported infectious episodes during this period. However, patients who continue to have no B‐cells or memory B‐cells, and those who lack IgA and IgM and with conditions such as CLL, where hypogammaglobulinemia is commonly progressive over time, are likely to experience increased number of severe infections due to immunodeficiency, once prophylaxis is stopped.12

In view of these heterogeneous treatment guidelines for SID in patients with hematological malignancies, assessing current clinical practice is of great interest. We present an international online survey on the daily clinical practice of SID diagnosis and treatment in hematological malignancies. The aim of the survey was to document current treatment practices and challenges in SID across countries and to identify discrepancies between treatment indications, treatment recommendations, and daily practice as well as regional differences in SID treatment.

2. METHODS

The online survey was conducted in January and February 2018 and was open to physicians from the United States, Canada, the UK, France, Italy, Spain, and Germany. Qualified physicians included immunologists, hematologists/oncologists, internal medicine specialists, and pediatricians. In order to participate, all physicians had to be responsible for the diagnosis of SID and the prescription of Ig treatment in patients with hematological malignancies. Additionally, hematologists and oncologists had to have cared for at least 20 patients with hematological malignancies over the last 12 months. For other medical specialties, the minimal number of patients cared for with hematological malignancies over the last 12 months was five. The survey questionnaire is provided as a Supplementary Material. Data used with permission from third‐party source. All rights reserved.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Survey population

In total, 230 physicians from the United States (N = 50), Canada, the UK, France, Italy, Spain, and Germany (N = 30 each) participated in the survey (Table 1). Hematologists/oncologists represented at least 50% of physicians in all countries and 90% of all participants had 5 years of clinical experience or more. Overall, surveyed physicians spent the major part of their time in university/teaching hospitals and less in other hospitals, private practices, and/or outpatient clinics. Of all participants, 59% (N = 135) practiced exclusively in one care setting with 64% of those (N = 87) working exclusively in university/teaching hospitals.

Table 1.

Respondent and patient characteristics

| Parameter | Canada | France | Germany | Italy | Spain | UK | USA | Pooled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 50 | 230 |

| Specialty, n (%) | ||||||||

| Hematologist/Oncologist | 16 (53) | 21 (70) | 23 (77) | 21 (70) | 19 (63) | 23 (77) | 25 (50) | 148 (64) |

| Immunologist | 5 (17) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 3 (10) | 9 (30)a | 3 (10) | 10 (20) | 32 (14) |

| Internal medicine | 3 (10) | 5 (17) | 2 (7) | 3 (10) | 1 (3) | 2 (7) | 10 (20) | 26 (11) |

| Pediatrician | 6 (20) | 2 (7) | 4 (13) | 3 (10) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 5 (10) | 22 (10) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Clinical experience, n (%) | ||||||||

| <5 y | 3 (10) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 5 (17) | 3 (10) | 1 (3) | 5 (10) | 18 (8) |

| 5‐15 y | 16 (53) | 12 (40) | 16 (53) | 11 (37) | 17 (57) | 21 (70) | 24 (48) | 117 (51) |

| >15 y | 11 (37) | 17 (57) | 14 (47) | 14 (47) | 10 (33) | 8 (27) | 21 (42) | 95 (41) |

| Directly responsible for diagnosis of SID and prescription of IgG, n (%) | 24 (80) | 29 (97) | 29 (97) | 28 (93) | 26 (87) | 27 (90) | 45 (90) | 208 (90) |

| Number of patients cared for per respondent, n, median | ||||||||

| CLL | 15 | 40 | 50 | 30 | 23 | 35 | 20 | 213 |

| MM | 15 | 39 | 46 | 45 | 21 | 38 | 15 | 219 |

| NHL | 10 | 33 | 60 | 50 | 33 | 31 | 25 | 242 |

| Other lymphoproliferative diseases | 10 | 20 | 23 | 35 | 20 | 18 | 15 | 141 |

| All indications | 50 | 132 | 179 | 160 | 97 | 122 | 75 | 815 |

| Patients cared for with severe or recurring infections, n (% patients) | ||||||||

| CLL | 398 (34) | 335 (28) | 655 (35) | 730 (29) | 461 (38) | 280 (21) | 496 (25) | 3355 (30) |

| MM | 263 (26) | 371 (30) | 454 (29) | 521 (25) | 314 (31) | 292 (23) | 489 (26) | 2704 (27) |

| NHL | 300 (26) | 341 (26) | 677 (27) | 531 (27) | 326 (26) | 219 (18) | 400 (20) | 2794 (24) |

| Other lymphoproliferative diseases | 193 (27) | 241 (24) | 399 (24) | 424 (27) | 311 (27) | 135 (19) | 368 (22) | 2071 (24) |

| Patients cared for with hypogammaglobulinemia (IgG < 4 g/L), n (% of patients) | ||||||||

| CLL | 369 (32) | 433 (36) | 631 (34) | 911 (36) | 438 (36) | 366 (27) | 609 (31) | 3721 (33) |

| MM | 241 (24) | 446 (36) | 403 (25) | 720 (35) | 339 (34) | 405 (32) | 505 (27) | 3043 (30) |

| NHL | 247 (22) | 362 (28) | 593 (24) | 490 (25) | 347 (28) | 173 (14) | 478 (24) | 2669 (23) |

| Other lymphoproliferative diseases | 196 (28) | 331 (32) | 365 (22) | 379 (24) | 319 (28) | 112 (16) | 396 (23) | 2086 (25) |

CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; MM, multiple myeloma; NHL, non‐Hodgkin lymphoma.

Includes four physicians classified as allergists/immunologists.

Immunologists represented 14% (N = 32) of all physicians and were mainly based in the United States (31%) and Spain (28%). The number of patients with CLL, MM, and NHL cared for was similar across all countries, indicating that the survey was not influenced by indication bias.

3.2. Recurring infections

On average, CLL and MM patients were more likely to develop severe or recurring infections (30% and 27%) than patients with NHL or other lymphoproliferative diseases (24% each; Table 1). Similarly, CLL and MM patients were more likely to develop hypogammaglobulinemia (33% and 30%), defined as IgG levels <4 g/L, than those with NHL or other lymphoproliferative diseases (23% and 25%). There was some variation across countries (Table 1). Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) was performed in 14%, 25%, 19%, and 15% of patients with CLL, MM, NHL, and other lymphoproliferative diseases, respectively. Patients with MM and NHL received autologous HSCT (73% and 69%) much more frequently than allogenic HSCT (27% and 31%). Patients with CLL or other lymphoproliferative diseases underwent autologous (51% and 57%) and allogenic (49% and 43%) HSCT in comparable proportions. HSCT status had little impact on reported rates of severe or recurring infections (average of 26%‐32% across all diseases) and hypogammaglobulinemia (average of 24%‐30% across all diseases).

3.3. Monitoring and diagnostic practice

Overall, serum Ig levels were measured in 83% of MM patients, 76% of CLL patients, 69% of NHL patients, and 69% of patients with other lymphoproliferative diseases (Table 2). Ig levels in NHL patients or with other lymphoproliferative diseases were more frequently measured by physicians spending at least 50% of their time in the university setting in Canada, Spain, and Italy (in about 80% of their patients). Nearly all physicians measured IgG levels (92%‐100% across all countries), and most physicians measured IgA and IgM levels (68%‐90% across all countries; Table 2). IgG subclasses were frequently measured by physicians in Spain (60%), Italy (43%), and the United States (40%), and by nearly a third of physicians in Germany, Canada, and the UK. Most physicians (82%) measured Ig serum levels in all patients after two or more severe infections, 68% and 69% of physicians measured Ig before and after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and 64% after first severe infection (Table 2).

Table 2.

Monitoring and diagnostic practice

| Parameter | Canada | France | Germany | Italy | Spain | UK | USA | Pooled | Immunologists |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 | 50 | 230 | 32 |

| Ig classes measured, % | |||||||||

| IgG | 100 | 97 | 100 | 93 | 97 | 97 | 92 | 96 | 100 |

| IgA | 77 | 77 | 90 | 90 | 80 | 87 | 68 | 80 | 94 |

| IgM | 77 | 73 | 83 | 90 | 90 | 90 | 84 | 84 | 94 |

| IgG subclasses | 27 | 20 | 30 | 43 | 60 | 27 | 40 | 36 | 59 |

| Measurement of Ig levels sometimes, always, % | |||||||||

| At diagnosis of hematological malignancy | 47, 50 | 27, 73 | 40, 57 | 27, 73 | 27, 73 | 47, 50 | 36, 62 | 36, 62 | 41, 56 |

| After any infection occurs | 47, 50 | 60, 30 | 50, 50 | 43, 40 | 60, 30 | 67, 17 | 64, 30 | 56, 35 | 50, 41 |

| After the first lower respiratory tract infection | 61, 29 | 53, 40 | 70, 30 | 53, 40 | 47, 33 | 53, 17 | 66, 26 | 58, 30 | 55, 34 |

| After the first severe infection | 40, 60 | 40, 57 | 37, 63 | 13, 87 | 13, 80 | 53, 40 | 34, 62 | 33, 64 | 22, 75 |

| After two or more severe infections | 30, 70 | 13, 87 | 17, 80 | 13, 87 | 10, 90 | 17, 77 | 14, 86 | 17, 82 | 6, 91 |

| During chemotherapy treatment | 57, 23 | 60, 20 | 70, 27 | 50, 43 | 60, 30 | 67, 17 | 56, 34 | 59, 28 | 53, 41 |

| After chemotherapy treatment | 57, 37 | 50, 43 | 40, 53 | 47, 50 | 57, 40 | 67, 17 | 54, 40 | 52, 40 | 44, 56 |

| Before HSCT | 23, 70 | 30, 70 | 20, 77 | 23, 77 | 20, 80 | 50, 43 | 28, 66 | 28, 68 | 6, 84 |

| After HSCT | 33, 60 | 23, 77 | 23, 77 | 20, 80 | 20, 80 | 43, 50 | 32, 66 | 28, 69 | 19, 78 |

| Measurement of specific antibody responses, % | |||||||||

| No | 40 | 47 | 33 | 37 | 27 | 47 | 42 | 38 | 6 |

| Yes, always | 7 | 3 | 7 | 27 | 17 | 3 | 14 | 11 | 28 |

| Yes, in the following cases: | |||||||||

| Before and after vaccination (ie, test immunization) | 37 | 33 | 50 | 20 | 47 | 47 | 36 | 38 | 59 |

| After lower respiratory tract infection and low antibody responses | 17 | 30 | 27 | 20 | 30 | 27 | 18 | 23 | 25 |

| After lower respiratory tract infection and failure to respond to antibiotic prophylaxis | 27 | 30 | 40 | 23 | 30 | 27 | 22 | 28 | 38 |

| Performance of test immunization, % | |||||||||

| No | 50 | 77 | 80 | 53 | 43 | 77 | 62 | 63 | 25 |

| Sometimes | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Yes | 43 | 23 | 20 | 43 | 53 | 17 | 34 | 33 | 68 |

HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation; Ig, immunoglobulin.

The measurement of specific antibody responses varied across countries (Table 2). Over one‐third of respondents (38%) did not measure specific antibody responses in general. Spanish, Italian, and USA physicians measured specific antibody responses more frequently than physicians overall, probably due to the higher proportion of immunologists in these countries included in the survey. Specific antibody responses were mostly measured before and after vaccination (referred to as test immunization).

Specifically, overall, 33% of respondents performed test immunization with high variability observed between countries. While Italian (43%), Spanish (53%), and Canadian (43%) physicians performed test immunization more frequently than the average, in the UK (17%), Germany (20%), and France (23%), test immunization was particularly rare.

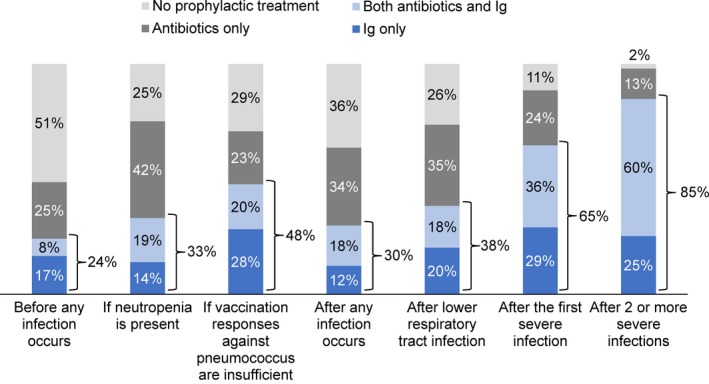

3.4. Choice of infection prophylaxis

Prophylactic IgRT in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia was mostly prescribed after two or more severe infections (85% of physicians) or after the first severe infection (65% of physicians; Figure 1 and Table S1). IgRT prescription practice was generally comparable across most countries, but there was some variation (Table S1). In Italy, Germany, Spain, and the United States, Ig use in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia was generally above average. The combined use of Ig and antibiotics was slightly more widespread in the United States compared with Europe. Concomitant use of Ig and antibiotics was particularly rare in the UK, where Ig use was much less pronounced and antibiotic use was much more prominent. In the UK, only 3% or less physicians used both antibiotics and Ig after insufficient vaccination response against pneumococcus, after any infection, and after lower respiratory tract infection. The combination of Ig and antibiotics was half as frequent in the UK after the first severe infection (17%) and after two or more severe infections (30%) compared with the average across all countries (36% and 60%, respectively).

Figure 1.

Infection prophylaxis across all countries in patients with hypogammaglobulinemia (USA [N = 50], Canada, the UK, France, Italy, Spain, and Germany [N = 30 each])

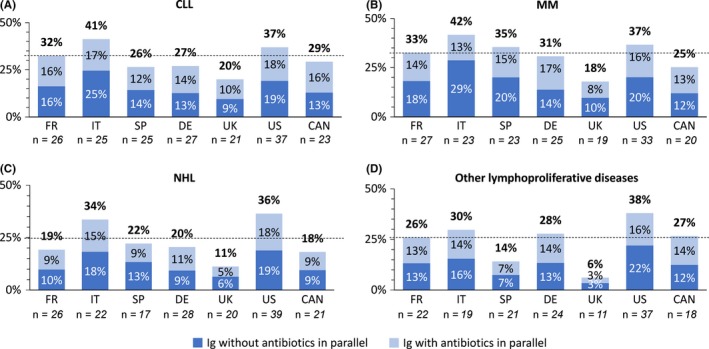

3.5. Treatment with IgRT by indication

The average proportion of patients reportedly treated with Ig alone and/ or in parallel with antibiotics was comparable across CLL (32%), MM (33%), NHL (25%), and other lymphoproliferative diseases (26%), with approximately one‐quarter to one‐third of patients being treated across each indication (Figure 2). There were some regional differences in the frequency of IgRT across indications. Patients in Italy and the United States were more frequently treated with Ig across all indications. In the UK, considerably fewer patients received IgRT, particularly in NHL (11%) and other lymphoproliferative diseases (6%). In contrast, patients in Italy and the United States were more frequently treated with Ig across all indications. Furthermore, US physicians practicing at least 50% of their time in university hospitals treated a higher number of patients with Ig therapy compared to the average (CLL: 42%, MM: 36%, NHL: 54%, other lymphoproliferative diseases: 59%).

Figure 2.

Average proportion of patients with (A) chronic lymphocytic leukemia, (B) multiple myeloma, (C) non‐Hodgkin lymphoma, and (D) other lymphoproliferative diseases, treated with Ig, with or without antibiotics in parallel over the last 12 mo. The dashed line indicates the average of patients treated with Ig, with or without antibiotics in parallel across all countries (CLL [32%], MM [33%], NHL [25%], and other lymphoproliferative diseases [26%]). Patients referred for Ig treatment are excluded, as for these patients no information on antibiotic usage was available. The values for average proportion of patients treated with Ig differed marginally when including referred patients

3.6. Route of administration and dose

The reported use of SCIG was highest in France (34%) followed by the United States (30%), Italy (27%), and Germany (25%). Lowest SCIG use was reported in Spain (19%) preceded by the UK (21%) and Canada (22%). The average initial monthly starting dose of IgG was 0.35 g/kg body weight (BW). Higher doses of 0.4‐0.5 g/kg BW were prescribed by 70% of immunologists (n = 32). No substantial differences were observed between countries.

3.7. Duration of treatment

Over 80% of physicians prescribed Ig regardless of the season. The reported mean Ig treatment duration was comparable across countries and indications with 10‐12 months, ranging from 1 to 60 months (Table S2). Physicians in Italy reported the shortest treatment durations across all indication with a mean of 7 months, probably due to tighter cost control in these countries. The main reasons reported for discontinuing Ig therapy were no infection for 12 months and adequate specific antibody response by 39% of physicians, followed by no infections for 6 months by 26% of physicians. IgG trough levels were reported as the main reason for discontinuing Ig therapy by 17% of all physicians but 37% of French physicians.

3.8. Immunologist responses

Immunologists followed recommendations more closely than oncologists/hematologists overall. Only 6% of immunologists (n = 32) did not measure specific antibody responses compared to 38% of physicians. Over two‐thirds of immunologists reported performing test immunizations whereas only one‐third of physicians did (Table 2). Immunologists prescribed Ig in more patients (CLL: 63%, MM: 54%, NHL: 47%, other: 27%), than physicians (CLL: 32%, MM: 33%, NHL: 25%, other: 26%), possibly because most patients were referred to the immunologists specifically for Ig treatment. Immunologists also used Ig more often than physicians before any infection occurred and when vaccination responses were insufficient. Immunologists used higher doses of IgG, with 70% using initial monthly doses of 0.4‐0.5 g/kg BW compared with 45% of physicians across all countries. Immunologists also used SCIG more frequently than physicians (44% vs 25%).

4. DISCUSSION

Two recent publications reported data on the management of SID in patients with malignancies: the prospective, observational German SIGNS study, and a survey among British and Irish immunologists on the prescription practice of IgRT in SID.23, 24 The present online survey of 230 physicians identifies a discrepancy between approved indications, published recommendations, and daily routine in the treatment of SID in patients with hematological malignancies on an international level.

Approved indications for Ig products differ between countries. In Canada, IVIG and SCIG concentrates are generally indicated for use in SID.25, 26 In the EU, as of 2019 the approved indications for IVIG in SID have been widened from patients with CLL, MM and patients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation,28, 29 to patients who suffer from severe or recurrent bacterial infections, ineffective antibiotic treatment and either proven specific antibody failure (failure to mount at least a two‐fold rise in IgG antibody titer to pneumococcal polysaccharide and polypeptide antigen vaccines) or serum IgG level of <4 g/L.30 In the USA, only a single Ig concentrate is approved for use in CLL.31 No other products are approved for other hematological malignancies, and SCIG is only approved for PID.32

National recommendations for the use of IgRT in SID in patients with hematological malignancies are generally not aligned with the approved indications in the corresponding country. For example, in the United States, the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI) recommend that treatment should be considered in patients with CLL or MM, after lymphoma treatment with B‐cell‐depleting therapies, and in patients who are hypogammaglobulinemic with recurrent bacterial infections and subprotective antibody levels after immunization against diphtheria, tetanus, or pneumococcal infection.32 In Germany, prophylactic use of Ig is recommended in hypogammaglobulinemic patients with malignant lymphoma, MM, and chronic immunosuppression with at least three severe bacterial infections in the respiratory, gastrointestinal, or urogenital system or sepsis per year.33 In the UK, the Department of Health recommended selection criteria for IgRT of hypogammaglobulinemia associated with non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), CLL, MM, or other relevant B‐cell malignancy in combination with recurrent or severe bacterial infection despite continuous oral antibiotic therapy for 3 months, IgG <5 g/L (excluding paraprotein) and documented failure of serum antibody response to unconjugated pneumococcal or other polysaccharide vaccine challenge. In Canada, prophylactic IVIG is recommended in adult patients with hematologic malignancies who have had a recent life‐threatening infection or recurrent episodes of clinically significant infections (eg, pneumonia), if these infections are thought to be caused by low levels of polyclonal Ig.22

Treatment application was comparable across the countries, indicating that country‐specific approval status of Ig concentrates does not influence the daily practice of physicians. Despite IgRT not being approved for malignancies other than CLL in the United States and additionally for MM in Europe at the time of the survey, serum Ig levels were widely monitored across CLL, MM, NHL, and other lymphoproliferative diseases and IgRT administered across all these malignancies. In the United States, which has the most restricted indication, IgRT was prescribed equally in CLL, MM, NHL, and other lymphoproliferative diseases and used considerably more frequently within each indication than generally in Europe (except in Italy) and Canada (Figure 2). In addition, 30% of USA physicians prescribed SCIG, despite it not being approved in SID. These data indicate harmonization of clinical practice, despite regional indication differences and the lack of harmonized treatment guidelines.

Although Ig levels were generally monitored in NHL and other lymphoproliferative diseases, a significant proportion of this subpopulation was reported to develop severe or recurring infections. In addition, in Canada, France, Germany, and the UK, the reported proportion of patients with NHL receiving infection prophylaxis with Ig was considerably lower than the proportion of patients with severe or recurring infections. This indicates that patients in this population could potentially benefit from IgRT and an increased awareness of the risk of infection due to SID. University physicians generally prescribed IgRT more frequently, possibly because they were likely to be dealing with patients suffering from more severe infections and access to Ig therapy might have been easier at university hospitals.

The abovementioned off‐label use of IgRT and the potentially unaddressed Ig‐eligible population indicate a need to extend the indications for IgRT in SID in Europe and the USA, and to increase the awareness for the risk of SID beyond CLL and MM.

A recent expert opinion on prophylactic IgRT in SID recommended against routine measurement of IgG subclasses due to the low incidence of pure IgG subclass deficiency and the limited evidence for correlation between infection rates and low levels of IgG subclasses in patients with normal IgG levels.11 In contrast, physicians frequently measured IgG subclasses, particularly in Spain, Italy, and the United States. This expert opinion and a recent review on IgRT in hematological malignancy stressed the importance of assessing and monitoring specific antibody responses.11, 34 In this online survey, over one‐third of respondents did not measure specific antibody responses, while immunologists were much more likely to measure specific antibody responses. Contrary to recommendations to systematically perform test immunizations in patients with SID, only one‐third (33%) of surveyed physicians did so on average.11 Over two‐thirds (68%) of immunologists performed test immunizations, which is in line with the data reported for British and Irish immunologists.24 These data indicate that immunologists follow the recommendations more closely. However, there is no evidence that increased monitoring results in improved outcomes (or less infection or decreased mortality) since supporting clinical data are lacking.

In contrast to German recommendations to initiate IgRT after at least three severe bacterial infections per year,33 German physicians frequently prescribed prophylactic IgRT after the first severe infection (67%), after lower respiratory infection (50%), after any infection occurs (47%), and even before any infection occurs (33%). These data are in line with findings of the German observational prospective SIGNS study, which reported that most of the patients newly treated with IgRT did not fulfill the German recommendations regarding the frequency of severe infections.23 This divergence between recommendations and clinical practice points to the need for clinical studies to evaluate the use of IgRT at an early stage in a patient's primary disease, as suggested previously.11, 34

The high reported use of prophylactic antibiotics in the UK is consistent with reports of 85% of British and Irish immunologists prescribing prophylactic antibiotics in all, or most, of their patients before starting Ig therapy.24 These observations might be explained by the inclusion of recurrent or severe bacterial infections despite continuous oral antibiotic therapy for 3 months as selection criteria for IgRT in the British clinical guidelines for Ig use.35

The reported use of SCIG was unexpectedly high, ranging from 19% to 34%. These numbers seem an overestimation of the actual use in these countries. For example, 6.5% of patients received SCIG in the recent German SIGNS study.23 Regional differences may be a consequence of national reimbursement policies.

The average initial monthly starting dose of IgG was 0.35 g/kg BW, which lies in the range of 0.2‐0.4 g/kg BW stated in most guidelines. In Europe, a dose of 0.2‐0.4 g/kg BW every 3‐4 weeks is recommended in the current IVIG core Summary of Product Characteristics.30 Similarly, Canadian recommendations state 0.4 g/kg BW every 3 weeks with re‐evaluation every 4‐6 months.22 In contrast, UK clinical guidelines for Ig use (Department of Health) have modified the dose recommendation from 0.4 g/kg BW/mo to “achieve an IgG trough level of at least the lower limit of the age‐specific serum IgG reference range,” while British guidelines for supportive care in MM suggest a dose of IVIG of 0.5 g/kg BW administered every month for up to 6 months.35, 36 Immunologists (n = 32) tended to prescribe higher doses of IgG than other physicians, with 70% of them prescribing doses in the range of 0.4‐0.5 g/kg BW. High doses may result from extrapolation of dosing in PID, which may be expected in the absence of clear guidelines in SID. In contrast to our findings, average monthly doses prescribed in Germany were recently reported to be around 0.2 g/kg BW.23

Comparable to numbers reported for clinical practice in Germany,23 over 80% of physicians used IgRT regardless of season. This contrasts with recommendations by Agostini et al11 who suggest seasonal discontinuation of treatment during late spring and summer months. In line with recommendations were the reported duration of 10‐12 months and the reported main reasons for discontinuing Ig therapy, no infection for 12 months and adequate specific antibody response.11

Notably, data were collected from physicians rather than from patient records. In addition, the proportion of patients with hypogammaglobulinemia and/ or severe infections as separate or concomitant events was not analyzed. Furthermore, it might be of interest to further stratify the reported data by diseases grouped as “other lymphoproliferative diseases.” This study did not capture data on chemotherapeutic medication used to treat the different hematological malignancies. In future studies, it would be interesting to assess how different B‐cell targeting therapies across the investigated disease entities impact on the incidence and management of SID.

5. CONCLUSIONS

The survey revealed discrepancies among daily practice, clinical practice, guideline recommendations, and currently approved indications. This underlines the medical need for more evidence from robust clinical trials, especially in hematological malignancies other than CLL and MM, in order to optimize the risk stratification of patients and to guide the identification of those patients likely to benefit from IgRT.

Despite regional indication differences, IgRT use was overall comparable across the countries. Moreover, although IgRT is not indicated for SID in hematological malignancies other than CLL in the United States and CLL and MM in Europe, physicians widely used IgRT in MM, NHL, and other hematological diseases. High regional variability and/or deviations from current treatment recommendations were observed in the monitoring of IgG subclasses, measurement of specific antibody responses, performance of test immunization, and treatment duration. Overall, immunologists followed recommendations to measure specific antibody responses and perform test immunizations much more closely than hematologists/oncologists, suggesting that closer collaboration between immunologists and hematologist/oncologists could be beneficial for the management of SID. This large, international survey of different specialists involved in the care of patients with malignancies with SIDs demonstrated that harmonized evidence‐based diagnostic and treatment guidelines in SID in hematological diseases are needed.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

IN has served as speaker and consultant for Baxalta/Shire and Octapharma and has received research funding from Neovii and Baxalta/Shire. MB has acted as consultant for Octapharma and CSL. CA has participated in advisory board meetings for InterMune/Roche, Inc, CSL Behring GmbH, Inc, Shire, Inc, Octapharma, Inc His institution (Dipartimento di Medicina) received grants from InterMune/Roche, Inc, CSL Behring GmbH, Inc, Baxter International, Inc, Boehringer Ingelheim, Actelion, Inc, Gilead, Inc, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Comp. JDME has received fees for speaking (Shire Israel), and consulting (Shire UK, Octapharma UK). VF has received honoraria for lectures from Gilead, Octapharma, Baxalta/Shire, Pfizer, CSL Behring, Astellas. MM received honoraria for participating in advisory boards for Astellas, Neovii, and Octapharma. SSR has served as speaker, consultant, and advisory board member for, or has received research funding from, Grifols, CSL Behring, Shire, and Octapharma. CS has received speaking honoraria and travel expenses for scientific meetings (CSL Behring, Octapharma, Shire), has participated in advisory boards of clinical trials (CureVac, HDIT) and has received grants for clinical studies (CSL Behring, Octapharma, Shire). IQ has received grants from Kedrion, CSL Behring, Octapharma, and Shire.

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All authors designed and reviewed the survey questionnaire, contributed to data interpretation, and reviewed the manuscript. IN and IQ contributed to data analysis and writing of the manuscript. Medical writing support was provided by Dr Marie Lis Kirsten from nspm ltd (Meggen, Switzerland).

Na I‐K, Buckland M, Agostini C, et al. Current clinical practice and challenges in the management of secondary immunodeficiency in hematological malignancies. Eur J Haematol. 2019;102:447–456. 10.1111/ejh.13223

Funding information

This research was financially supported by Octapharma.

REFERENCES

- 1. Jolles S, Chapel H, Litzman J. When to initiate immunoglobulin replacement therapy (IGRT) in antibody deficiency: a practical approach. Clin Exp Immunol. 2017;188:333‐341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kaplan B, Kopyltsova Y, Khokhar A, Lam F, Bonagura V. Rituximab and immune deficiency: case series and review of the literature. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:594‐600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Casulo C, Maragulia J, Zelenetz AD. Incidence of hypogammaglobulinemia in patients receiving rituximab and the use of intravenous immunoglobulin for recurrent infections. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2013;13:106‐111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hamblin AD, Hamblin TJ. The immunodeficiency of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br Med Bull. 2008;87:49‐62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Raanani P, Gafter‐Gvili A, Paul M, Ben‐Bassat I, Leibovici L, Shpilberg O. Immunoglobulin prophylaxis in hematological malignancies and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD006501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Oscier D, Dearden C, Eren E, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis, investigation and management of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:541‐564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dhalla F, Lucas M, Schuh A, et al. Antibody deficiency secondary to chronic lymphocytic leukemia: should patients be treated with prophylactic replacement immunoglobulin? J Clin Immunol. 2014;34:277‐282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Augustson BM, Begum G, Dunn JA, et al. Early mortality after diagnosis of multiple myeloma: analysis of patients entered onto the United kingdom Medical Research Council trials between 1980 and 2002–Medical Research Council Adult Leukaemia Working Party. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9219‐9226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Blimark C, Holmberg E, Mellqvist UH, et al. Multiple myeloma and infections: a population‐based study on 9253 multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica. 2015;100:107‐113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chapel Hm, Lee M, Hargreaves R, et al. Randomised trial of intravenous immunoglobulin as prophylaxis against infection in plateau‐phase multiple myeloma. The UK group for immunoglobulin replacement therapy in multiple myeloma. Lancet. 1994;343:1059‐1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Agostini C, Blau IW, Kimby E, Plesner T. Prophylactic immunoglobulin therapy in secondary immune deficiency ‐ an expert opinion. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2016;12:921‐926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Compagno N, Malipiero G, Cinetto F, Agostini C. Immunoglobulin replacement therapy in secondary hypogammaglobulinemia. Front Immunol. 2014;5:626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chapel H, Dicato M, Gamm H, et al. Immunoglobulin replacement in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a comparison of two dose regimes. Br J Haematol. 1994;88:209‐212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cooperative Group for the Study of Immunoglobulin in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia , Gale RP, Chapel HM, et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for the prevention of infection in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. A randomized, controlled clinical trial. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:902‐907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Raanani P, Gafter‐Gvili A, Paul M, Ben‐Bassat I, Leibovici L, Shpilberg O. Immunoglobulin prophylaxis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and multiple myeloma: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Leuk Lymphoma. 2009;50:764‐772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abolhassani H, Sadaghiani MS, Aghamohammadi A, Ochs HD, Rezaei N. Home‐based subcutaneous immunoglobulin versus hospital‐based intravenous immunoglobulin in treatment of primary antibody deficiencies: systematic review and meta analysis. J Clin Immunol. 2012;32:1180‐1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sewell WA, Kerr J, Behr‐Gross ME, Peter HH, Kreuth Ig Working Group . European consensus proposal for immunoglobulin therapies. Eur J Immunol. 2014;44:2207‐2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Compagno N, Cinetto F, Semenzato G, Agostini C. Subcutaneous immunoglobulin in lymphoproliferative disorders and rituximab‐related secondary hypogammaglobulinemia: a single‐center experience in 61 patients. Haematologica. 2014;99:1101‐1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berger M. Subcutaneous administration of IgG. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:779‐802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jolles S, Orange JS, Gardulf A, et al. Current treatment options with immunoglobulin G for the individualization of care in patients with primary immunodeficiency disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2015;179:146‐160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sediva A, Chapel H, Gardulf A, et al. Europe immunoglobulin map. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014;178(Suppl 1):141‐143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Anderson D, Ali K, Blanchette V, et al. Guidelines on the use of intravenous immune globulin for hematologic conditions. Transfus Med Rev. 2007;21:S9‐56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reiser M, Borte M, Huscher D, et al. Management of patients with malignancies and secondary immunodeficiencies treated with immunoglobulins in clinical practice: long‐term data of the SIGNS study. Eur J Haematol. 2017;99:169‐177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Edgar J, Richter AG, Huissoon AP, et al. Prescribing immunoglobulin replacement therapy for patients with non‐classical and secondary antibody deficiency: an analysis of the practice of clinical immunologists in the UK and Republic of Ireland. J Clin Immunol. 2018;38:204‐213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Octapharma Canada Inc . PANZYGA® product monograph. 2017. https://www.octapharma.ca/fileadmin/user_upload/octapharma.ca/Product_Monographs/PANZYGA-PM-EN.pdf. Accessed September 07, 2018.

- 26. Grifols Canada Ltd . FLEBOGAMMA® 10% product monograph. 2017. https://pdf.hres.ca/dpd_pm/00040769.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2018.

- 27. CSL Behring Canada Inc . Privigen® product monograph. 2018. http://labeling.cslbehring.ca/PM/CA/Privigen/EN/Privigen-Product-Monograph.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2018.

- 28. European Medicines Agency . Guideline on core SmPC for human normal immunoglobulin for intravenous administration (IVIg). 2012. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2012/12/WC500136433.pdf. Accessed May 18, 2018.

- 29. European Medicines Agency . Guideline on core SmPC for human normal immunoglobulin for subcutaneous and intramuscular administration. 2015. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2015/03/WC500184870.pdf. Accessed May 14, 2018.

- 30. European Medicines Agency . Guideline on core SmPC for human normal immunoglobulin for intravenous administration (IVIg). 2018. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Scientific_guideline/2018/07/WC500252345.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2018.

- 31. Baxalta US Inc . GAMMAGARD S/D full prescribing information. 2017. https://www.fda.gov/downloads/BloodBloodProducts/UCM197905.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2018.

- 32. Perez EE, Orange JS, Bonilla F, et al. Update on the use of immunoglobulin in human disease: a review of evidence. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:S1‐S46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bundesärztekammer . Querschnitts‐leitlinien (BÄK) zur therapie mit blutkomponenten und plasmaderivaten. 2014.

- 34. Sanchez‐Ramon S, Dhalla F, Chapel H. Challenges in the role of gammaglobulin replacement therapy and vaccination strategies for hematological malignancy. Front Immunol. 2016;7:317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Department of Health . Clinical guidelines for immunoglobulin use: update to second edition. 2011. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/216671/dh_131107.pdf. Accessed May 17, 2018.

- 36. Snowden JA, Ahmedzai SH, Ashcroft J, et al. Guidelines for supportive care in multiple myeloma 2011. Br J Haematol. 2011;154(1):76‐103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials