Abstract

Aims

The gut microbiota has a great effect on the health and nutrition of the host. Manipulation of the intestinal microbiota may improve animal health and growth performance. The objectives of our study were to characterize the faecal microbiota between wild and captive Tibetan wild asses and discuss the differences and their reasons.

Methods and Results

Through high‐throughput sequencing of the 16S rRNA V4‐V5 region, we studied the gut microbiota composition and structure of Tibetan wild asses in winter, and analysed the differences between wild and captive groups. The results showed that the most common bacterial phylum in Tibetan wild ass faeces samples was Bacteroidetes, while the phylum Firmicutes was dominant in captive Tibetan wild ass faecal samples. The relative abundance of Firmicutes, Tenericutes and Spirochaetes were significantly higher (P < 0·01) than in the wild groups.

Conclusions

Captivity reduces intestinal microbial diversity, evenness and operational taxonomic unit number due to the consumption of industrial food, therefore, increasing the risk of disease prevalence and affecting the health of wildlife.

Significance and Impact of the Study

We studied the effect of the captive environment on intestinal micro‐organisms. This article provides a theoretical basis for the ex‐situ conservation of wild animals in the future.

Keywords: 16S rRNA sequencing, captive, gut microbiota, The Qinghai‐Tibet Plateau, Tibetan wild ass (Equus kiang)

Introduction

The Qinghai‐Tibetan plateau provides one of the most extreme environments for the survival of humans and other mammals (Zhang et al. 2016). The Tibetan wild ass (Equus kiang) is a unique species on the Qinghai‐Tibetan plateau and is widely distributed in Qinghai, Gansu, Xinjiang, Sichuan and Tibet (Wu and Yi 2000; Moehlman 2002). It is a key protected species in China and is listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List 2012 of threatened species. Intensive research has been performed regarding the conservation of this species (Joseph and Bard‐Jorgen 2005; Yifan and Jianping 2006; Yin et al. 2007; St‐Louis and Côté 2009; Kefena et al. 2012; Dong et al. 2015; Guo et al. 2018). With the development of wildlife protection plans, the change in environment during ex‐situ conservation comes with a change in animal health.

The microbial community of the gastrointestinal tract remains balanced in terms of species, quantity and location in healthy organisms. Animal intestines have large, diverse and dynamically changing bacterial communities that play important roles in host immunity, nutrient metabolism and energy acquisition (Yun et al. 2017). The composition of the mammalian gut microflora is associated with many environmental factors, among which living conditions are a major part (Guan et al. 2016).

Captive environments affect the composition of gut microbe in wild animals (Xenoulis et al. 2010; Guan et al. 2016, 2017). Changes in the intestinal microbe composition are associated with host health and disease (Quigley 2010; Costa et al. 2012; Morgan et al. 2012; Qin et al. 2012). Diet is a key factor affecting microbial diversity in the host gut (Ley et al. 2008; Yin et al. 2017; Qin et al. 2018). As industrial food consumption increases in humans and wildlife, each dietary change is accompanied by an adjustment of intestinal microbes, resulting in the loss or extinction of certain intestinal microbes (Zhang et al. 2018). Recent studies have shown that diet‐induced loss of microbial diversity can be amplified over generations, resulting in reduced intestinal microbial diversity and increased risk of population extinction (Sonnenburg et al. 2016).

Therefore, the objectives of our study were (i) to characterize the faecal microbiota between wild and captive Tibetan wild asses; (ii) to analyse the differences between faecal samples from different environments; (iii) discuss the causes for the differences, and finally, (iv) to explore the relationship between diet, gut flora and host health. The study of intestinal microbial diversity, which can be used to assess host health and related diseases, provide a theoretical basis for the future breeding or release of wild animals.

Materials and methods

Faecal samples from Tibetan wild asses living in the wild were collected from different regions of the headwaters of the Yellow River, Maduo County on Qinghai‐Tibet Plateau in January 2018. A total of 140 wild Tibetan wild ass faecal samples were collected. All samples were collected after natural defecation. Animals were not scared, nor driven, and drugs were not used to promote defecation. Captive Tibetan wild ass faecal samples were collected from the Qinghai‐Tibet Plateau wild animal park in January 2018. In total 28 captive Tibetan wild ass samples were collected. None of the animals had received anti‐inflammatory drugs or antimicrobials within the last 3 months.

All sample collection processes were performed in accordance with the requirements of the authorizing ethics committee.

Genomic DNA from the samples were extracted by the CTAB method. DNA purity and concentration were monitored on a 1% agarose gel. DNA samples were diluted to 1 ng μl−1 using sterile water. Universal 16S PCR primers (515F, 5′‐GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA‐3′ and 907R, 5′‐CCGTCAATTCCTTTGAGTTT‐3′) were used to amplify the V4 and V5 regions of the 16S rRNA. All PCR reactions were carried out with Phusion® High‐Fidelity PCR Master Mix (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). The polymerase chain reaction was carried out using the following mixture in a final volume of 30 μl: 10 μl of template DNA, 3 μl of each primer (6 μmol l−1), 15 μl of Phusion Master Mix (2×) and 2 μl of ddH2O. Next, DNA was amplified using the following conditions: denaturation for 1 min at 98°C, followed by 30 cycles of 10 s at 98°C for denaturation, 30 s at 50°C for annealing and 30 s at 72°C for extension, as well as a final extension step at 72°C for 5 min. The yield of PCR products was estimated using 2% agarose gel electrophoresis. PCR products were then purified with the GeneJETTM Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA).

The library was sequenced on an Ion S5™ XL platform and 400 bp single‐end reads were generated. The single‐end method was used to construct a small fragment library for single‐end sequencing. By cutting and filtering reads, OTUs (operational taxonomic units) were clustered and species annotation and abundance analysis were performed to reveal sample species composition.

Novogene was commissioned to complete all experiments (DNA extraction, PCR amplification, library preparation and sequencing) and data analysis.

All diversity indices in our samples were calculated with qiime (ver. 1.9.1) and displayed with R software (ver. 2.15.3). In R, NMDS analysis was displayed using the vegan package, principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) was displayed using the WGCNA package, stat package and ggplot2 package. Cluster analysis was preceded by principal component analysis (PCA), which was applied to reduce the dimensionality of the original variables using the factor Mine R package and ggplot2 package. Cross‐group and intra‐group differences were tested using the MRPP function in the vegan package.

Results

Eighty‐one faecal samples from wild and captive Tibetan wild asses were selected for sequencing, of which 60 samples were from wild animals (DY, DC and DZ), classified as the wild group (DYW), and 21 samples were from captive animals (DD1, DD2, DD3), classified as the captive group (DDD). A total of 4 809 901 high‐quality reads were obtained from wild group and classified into 3542 OTUs, while 1 693 293 high‐quality reads were obtained from the captive group and classified into 3155 OTUs. The number of OTUs present in both the wild and captive groups was 2928, with 614 unique OTUs in the wild group, and 227 unique OTUs in the captive group.

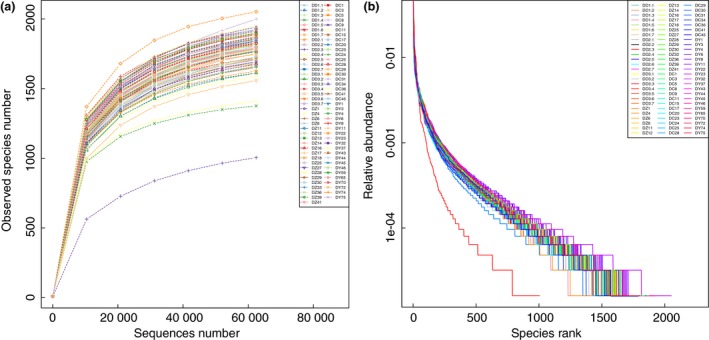

The rarefaction curves and rank abundance curves of the wild and the captive Tibetan wild ass faecal samples (Fig. 1) show the richness and evenness of the species in the samples. As the sample size increased, the number of observed species gradually stabilized and there were no further significant growth or fluctuations. The results show that the curve had reached a plateau and the sequencing data were reasonable. The number of samples in this study was sufficient to study the intestinal microbial diversity of Tibetan wild asses in the field and in captivity.

Figure 1.

Tibetan wild ass rarefaction curves (a) and rank abundance curve (b). [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

We detected a total of 27 phyla, 47 classes, 81 orders, 134 families and 241 genera from 81 Tibetan wild ass faecal samples. In the wild group, we detected 26 phyla, 44 classes, 74 orders, 117 families and 199 genera, while in the captive group, 26 phyla, 43 classes, 71 orders, 121 families and 204 genera were detected.

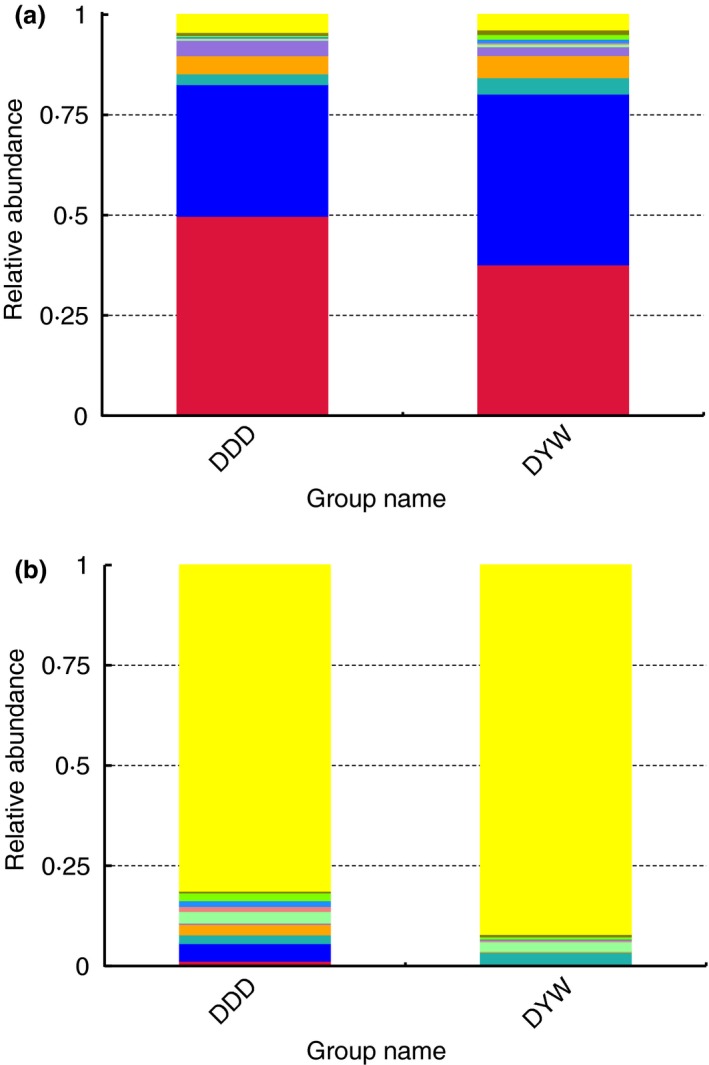

In the wild group, Bacteroidetes (42·59%) was the predominant phylum, and Anaerovorax (2·29%) was the predominant genus. In the captive group, Firmicutes (49·74%) was the predominant phylum, and Streptococcus (4·39%) was the predominant genus. In order to show the relative abundance of bacterial communities more intuitively, we have chosen the top 10 species for each sample or group and generated a percentage stacked histogram of relative abundance at the phylum and genus levels in Fig. 2.

Figure 2.

Relative abundance histogram. A histogram of the relative abundance of gut microbiota among groups in wild and captive Tibetan wild asses at the phylum level  others;

others;  Proteobacteria;

Proteobacteria;  Melainabacteria;

Melainabacteria;  Euryarchaeota;

Euryarchaeota;  Fibronacteres;

Fibronacteres;  Verrucomicrobia;

Verrucomicrobia;  Spirochaetes;

Spirochaetes;  Kiritimatiellaeota;

Kiritimatiellaeota;  Tenericutes;

Tenericutes;  Bacteroidetes;

Bacteroidetes;  Firmicutes (a) and genus level (b)

Firmicutes (a) and genus level (b)  others;

others;  Akkermansia;

Akkermansia;  unidentified_Spirochaetaceae;

unidentified_Spirochaetaceae;  Oribacterium;

Oribacterium;  unidentified_Prevotellaceae;

unidentified_Prevotellaceae;  unidentified_Ruminococcaceae;

unidentified_Ruminococcaceae;  Gillisia;

Gillisia;  unidentified_Clostridiales;

unidentified_Clostridiales;  unidentified_Bacteroidales;

unidentified_Bacteroidales;  Streptococcus;

Streptococcus;  Bacteroides. [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Bacteroides. [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The alpha diversity indices (including Shannon, Simpson, Chao1, ACE, Goods_coverage) are shown in Table 1 (cut‐off = 62 431). The Goods coverage index was above 99%, indicating a high level of diversity was found in the samples. The Shannon, Chao1 and ACE indices in the wild group were higher than in the captive group (P Shannon = 0·01627 < 0·05, P Chao1 = 0·000381 < 0·01, P ACE = 0·000838 < 0·01), but the Goods coverage index in the wild group was significantly lower than that in the captive group (P = 0·009368 < 0·01).

Table 1.

Alpha‐diversity of gut microbiota in faeces samples from wild and captive Tibetan wild asses

| Sample | Observed_species | Shannon | Simpson | Chao1 | ACE | Goods_coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DD1·1 | 1705 | 8·560 | 0·993 | 1812·014 | 1822·969 | 0·997 |

| DD1·2 | 1613 | 8·244 | 0·990 | 1704·377 | 1723·025 | 0·997 |

| DD1·3 | 1684 | 8·354 | 0·990 | 1772·946 | 1786·140 | 0·997 |

| DD1·4 | 1376 | 8·472 | 0·994 | 1452·703 | 1455·215 | 0·998 |

| DD1·5 | 1750 | 8·344 | 0·986 | 1880·569 | 1889·458 | 0·996 |

| DD1·6 | 1720 | 8·667 | 0·993 | 1810·725 | 1819·446 | 0·997 |

| DD1·7 | 1750 | 8·688 | 0·994 | 1850·665 | 1869·866 | 0·997 |

| DD2·1 | 1818 | 8·868 | 0·995 | 1920·097 | 1933·872 | 0·997 |

| DD2·2 | 1770 | 8·708 | 0·994 | 1885·545 | 1904·017 | 0·996 |

| DD2·3 | 1005 | 5·957 | 0·930 | 1152·396 | 1171·362 | 0·997 |

| DD2·4 | 1660 | 8·634 | 0·993 | 1773·305 | 1775·951 | 0·997 |

| DD2·5 | 1764 | 7·811 | 0·953 | 1875·000 | 1888·276 | 0·996 |

| DD2·6 | 1715 | 7·687 | 0·946 | 1810·174 | 1820·362 | 0·997 |

| DD2·7 | 1769 | 8·072 | 0·972 | 1900·790 | 1904·063 | 0·996 |

| DD3·1 | 1693 | 8·503 | 0·992 | 1847·962 | 1837·006 | 0·996 |

| DD3·2 | 1612 | 8·198 | 0·989 | 1738·196 | 1738·003 | 0·997 |

| DD3·3 | 1650 | 8·370 | 0·991 | 1785·631 | 1772·260 | 0·996 |

| DD3·4 | 1674 | 8·503 | 0·990 | 1774·000 | 1784·444 | 0·997 |

| DD3·5 | 1664 | 8·609 | 0·993 | 1774·571 | 1789·636 | 0·997 |

| DD3·6 | 1626 | 8·596 | 0·994 | 1744·719 | 1737·675 | 0·997 |

| DD3·7 | 1693 | 8·727 | 0·994 | 1788·050 | 1797·103 | 0·997 |

| DZ1 | 1874 | 8·582 | 0·990 | 1986·267 | 2013·325 | 0·996 |

| DZ4 | 1409 | 8·124 | 0·988 | 1500·838 | 1500·093 | 0·997 |

| DZ6 | 1793 | 8·523 | 0·991 | 1900·505 | 1905·494 | 0·997 |

| DZ8 | 1891 | 8·675 | 0·992 | 2035·361 | 2022·190 | 0·996 |

| DZ11 | 1831 | 8·748 | 0·993 | 1930·100 | 1937·509 | 0·997 |

| DZ12 | 1817 | 8·514 | 0·989 | 1921·659 | 1936·995 | 0·997 |

| DZ13 | 1788 | 8·657 | 0·993 | 1928·041 | 1924·393 | 0·996 |

| DZ14 | 1709 | 8·687 | 0·994 | 1812·000 | 1824·012 | 0·997 |

| DZ16 | 1810 | 8·649 | 0·993 | 1896·900 | 1915·408 | 0·997 |

| DZ17 | 1680 | 8·896 | 0·995 | 1765·562 | 1762·498 | 0·997 |

| DZ18 | 1861 | 8·869 | 0·995 | 2008·877 | 2011·590 | 0·996 |

| DZ25 | 1842 | 8·886 | 0·994 | 1928·671 | 1941·348 | 0·997 |

| DZ27 | 1840 | 8·688 | 0·990 | 1975·591 | 1978·662 | 0·996 |

| DZ28 | 1814 | 8·378 | 0·988 | 1982·125 | 1980·656 | 0·996 |

| DZ29 | 1771 | 8·452 | 0·990 | 1910·183 | 1914·916 | 0·996 |

| DZ30 | 1658 | 8·552 | 0·992 | 1752·031 | 1765·289 | 0·997 |

| DZ33 | 1867 | 8·720 | 0·993 | 1973·260 | 1997·880 | 0·996 |

| DZ36 | 1848 | 8·604 | 0·993 | 1997·638 | 2007·443 | 0·996 |

| DZ39 | 1765 | 8·444 | 0·989 | 1923·888 | 1899·486 | 0·996 |

| DZ41 | 1794 | 8·762 | 0·994 | 1933·087 | 1925·171 | 0·996 |

| DC1 | 1899 | 8·776 | 0·994 | 2054·793 | 2040·100 | 0·996 |

| DC3 | 1746 | 8·847 | 0·995 | 1834·033 | 1838·680 | 0·997 |

| DC5 | 1873 | 8·763 | 0·994 | 2035·515 | 2031·729 | 0·996 |

| DC8 | 1999 | 8·948 | 0·995 | 3207·036 | 2373·265 | 0·993 |

| DC9 | 1692 | 8·452 | 0·989 | 1811·929 | 1828·708 | 0·996 |

| DC11 | 1778 | 8·700 | 0·993 | 1882·046 | 1899·458 | 0·997 |

| DC15 | 1826 | 8·661 | 0·992 | 1918·130 | 1925·591 | 0·997 |

| DC17 | 1729 | 8·295 | 0·990 | 1898·375 | 1910·953 | 0·996 |

| DC20 | 1918 | 8·855 | 0·994 | 2045·401 | 2053·585 | 0·996 |

| DC23 | 1713 | 8·414 | 0·988 | 1827·895 | 1824·986 | 0·997 |

| DC24 | 1656 | 8·216 | 0·987 | 1791·264 | 1795·118 | 0·996 |

| DC25 | 1831 | 8·935 | 0·995 | 1960·242 | 1944·414 | 0·997 |

| DC28 | 1887 | 8·952 | 0·995 | 2027·000 | 2008·004 | 0·996 |

| DC29 | 1557 | 8·048 | 0·989 | 1668·467 | 1674·144 | 0·997 |

| DC30 | 1788 | 8·417 | 0·990 | 1896·005 | 1906·001 | 0·997 |

| DC31 | 1854 | 8·710 | 0·992 | 1963·000 | 1974·194 | 0·996 |

| DC34 | 1676 | 8·236 | 0·988 | 1812·573 | 1800·127 | 0·996 |

| DC36 | 1585 | 8·368 | 0·990 | 1706·731 | 1707·016 | 0·997 |

| DC41 | 1773 | 8·245 | 0·988 | 1921·479 | 1922·046 | 0·996 |

| DC45 | 1803 | 8·494 | 0·989 | 1949·250 | 1934·658 | 0·996 |

| DY1 | 1856 | 8·715 | 0·993 | 1935·377 | 1952·197 | 0·997 |

| DY3 | 1926 | 9·032 | 0·995 | 2054·211 | 2053·668 | 0·996 |

| DY4 | 1897 | 8·907 | 0·994 | 2026·814 | 2030·692 | 0·996 |

| DY6 | 1853 | 8·789 | 0·994 | 1955·511 | 1975·373 | 0·996 |

| DY8 | 1924 | 9·043 | 0·995 | 2036·718 | 2040·398 | 0·997 |

| DY11 | 1891 | 9·170 | 0·996 | 2002·132 | 1998·883 | 0·997 |

| DY22 | 2052 | 8·998 | 0·994 | 2177·845 | 2177·968 | 0·996 |

| DY23 | 1926 | 8·818 | 0·994 | 2084·049 | 2082·460 | 0·996 |

| DY32 | 1942 | 8·865 | 0·994 | 2116·527 | 2100·596 | 0·996 |

| DY37 | 1945 | 8·984 | 0·995 | 2072·467 | 2079·782 | 0·996 |

| DY43 | 1911 | 8·924 | 0·995 | 2040·868 | 2042·800 | 0·996 |

| DY44 | 1773 | 8·669 | 0·992 | 1865·205 | 1890·189 | 0·997 |

| DY45 | 1842 | 8·775 | 0·994 | 1951·120 | 1970·065 | 0·996 |

| DY46 | 1816 | 8·641 | 0·992 | 1979·125 | 1982·641 | 0·996 |

| DY59 | 1899 | 9·036 | 0·995 | 2006·622 | 2022·777 | 0·996 |

| DY65 | 1783 | 8·839 | 0·994 | 1902·691 | 1903·654 | 0·997 |

| DY70 | 1824 | 8·782 | 0·994 | 1947·142 | 1956·814 | 0·996 |

| DY72 | 1789 | 8·574 | 0·992 | 1900·500 | 1910·883 | 0·996 |

| DY74 | 1717 | 8·665 | 0·993 | 1816·569 | 1805·623 | 0·997 |

| DY75 | 1794 | 8·374 | 0·987 | 1927·526 | 1932·330 | 0·996 |

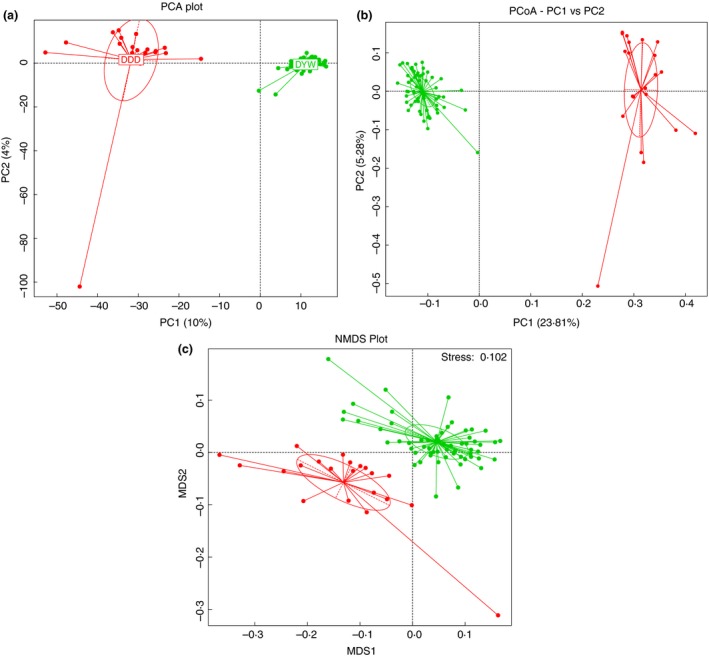

The PCA plot (Fig. 3a) and the PCoA plots (Fig. 3b) showed that the wild and the captive group formed two distinct areas on the graph. The similarity of the community structure was higher and the composition was more similar. The similarity between the two groups was obviously smaller than within the samples. In the PCA plot, the wild the captive groups were obviously separated, meaning that the similarity between the groups was small.

Figure 3.

The principal component analysis (PCA) of the gut microbiota of Tibetan wild asses in wild and captive groups (a). Principal coordinate analysis (PCoA) of the gut microbiota of Tibetan wild asses in wild and captive groups (b). NMDS analysis of gut microbiota of Tibetan wild asses from wild and captive collections (c) ( DDD;

DDD;  DYW). [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

DYW). [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

We also used a nonmetric multidimensional scaling (NMDS) plot to analyse discrepancies between the groups. Weighted and nonweighted methods were used for NMDS analysis, resulting in stress values of 0·088 and 0·102, respectively, which are both <0·2 indicating that NMDS can accurately differentiate the samples. NMDS is a nonlinear model, whether it is weighted analysis or nonweighted analysis, and the wild and captive groups were clearly separated. For individuals, different groups of individuals will also be clustered into the corresponding group, indicating that the difference between the two groups was quite remarkable (Fig. 3c). MRPP testing between the wild and captive groups was A = 0·1136 > 0. The difference between the groups was greater than the difference within the groups, indicating that the study groups were reasonable. The significance of 0·001 < 0·01, showed that the wild group and the captive group were significantly different.

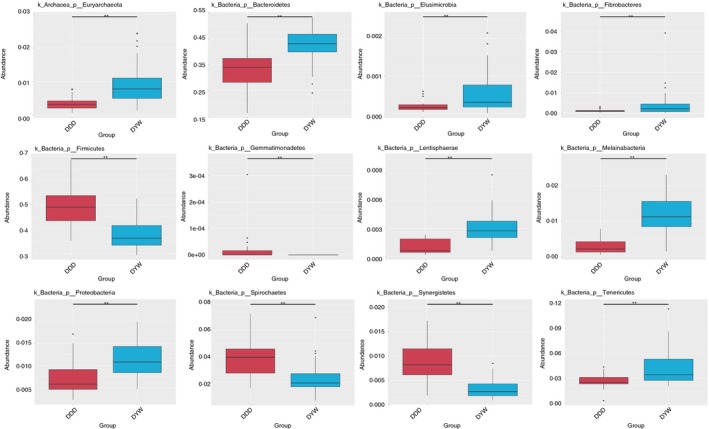

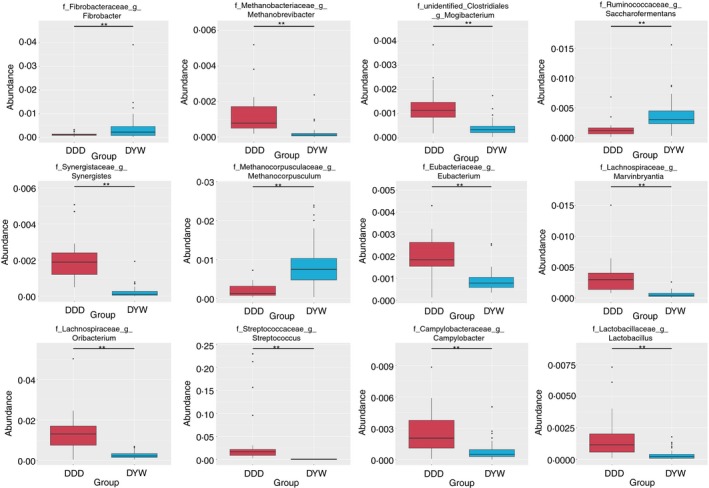

The Metastat method was used to test the microbial species abundance data for wild and captive faecal samples. According to the q value at the phylum level and genus there was a significant difference between the species (P < 0·01), and a plot of the difference between the species can be seen in the abundance distribution box map (Figs 4 and 5).

Figure 4.

Box diagram of species differences between wild and captive Tibetan wild asses at the phylum level. [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Figure 5.

Box diagram of species differences between wild and captive Tibetan wild asses at the genus level. [Colour figure can be viewed at http://wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Discussion

In the analysis of alpha diversity, the Shannon, Chao1 and ACE indexes of the wild group were larger than those of the captive group, which suggests that the bacterial diversity of gut microbes in the wild Tibetan wild ass population is significantly higher than for those individuals in captivity. Although the intestinal microbial diversity of the wild Tibetan wild ass was higher, fewer microbes were identified, and the exploration of wild animal intestinal flora has a broader prospect.

The Bacteroides and Firmicutes phyla made up more than 80% of the total bacterial content. This is consistent with previous studies of intestinal microbial diversity in mammals (Eckburg et al. 2005; Mariat et al. 2009; Middelbos et al. 2010; Qin et al. 2010; Van den Abbeele et al. 2010; Zhu et al. 2011; Guan et al. 2016) and these organisms facilitate the digestion of cellulose and hemicellulose in food (Wu et al. 2016). However, the numbers of bacteria from these two phyla were significantly different in the different host groups (P < 0·01). Bacteroidetes was the dominant phylum in the wild group, while Firmicutes was the dominant phylum in the captive group.

In winter, captive Tibetan wild asses are fed semi‐dry oat grass (fiber content 353·1 g kg−1), feed (protein 17·5%, fat 2%) and carrots (proportional to 8 : 2 : 1), and more fat and protein may reduce microbial diversity and lead to an increase in the number of Firmicutes and Actinobacteria (Zhang et al. 2012; He et al. 2013; Cani 2018). Thus the diversity of the gut microbiota was significantly lower in the captive group than in the wild group, with higher numbers of Actinobacteria and Firmicutes (Middelbos et al. 2010), and lower numbers of Bacteroidetes. The wild Tibetan wild asses feed mostly on Gramineae, Leguminosae and Cyperaceae plants, including pedicularis, Stipa purpurea, Brylkinia caudate, Poa annua, Carex myosuroides and Potentilla chinensis (Yin et al. 2007; Dong et al. 2015). In the wild, due to food shortage, protein and fat intake decreased, and the Bacteroidetes content increased to help host to increase their nutrition.

A disruption of the symbiosis between the microbiota and host is known as dysbiosis and is described in multiple chronic diseases, such as obesity and malnutrition (Castaner et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2018; Jeong et al. 2019), neurological disorders (Kurokawa et al. 2018; Quagliariello et al. 2018; Sun and Shen 2018), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (Costa et al. 2012; Roche‐Lima et al. 2018), metabolic syndrome (Zhao et al. 2018), cancer and other diseases (Katsimichas et al. 2018; Lu et al. 2018; Panebianco et al. 2018; Pulikkan et al. 2018; Zitvogel et al. 2018). We presume that the health of the wild group of Tibetan wild asses was better than the captive group. On the one hand, in the case of captivity, the feeding density is high and there is long‐term contact with human beings, with a higher probability of zoonosis among animals in captivity, and generally poorer health than animals in the wild. On the other hand, the intestinal microbial composition and content of the captive group was greatly altered, which can present as qualitative changes, such as increased proportions of harmful bacteria and reduced levels of beneficial bacteria. The captive Tibetan wild asses had more Spirochaetes, Proteobacteria and Campylobacter; groups of bacteria that contain pathogens (Ludwig et al. 2010), Proteobacteria is closely related to IBD and Clostridium difficile infection. Campylobacter is the most frequent cause of foodborne disease. At same time, the captive group samples had a lower content of Bacteroidetes, the basal microbiota, which is one of the richest phyla in a healthy human body and its levels can be a predictor of an animal's health.

In summary, there were significant differences in gut microbial composition and structure between wild and captive Tibetan wild asses. We believe that food, bacterial content and animal health are connected and changes in the numbers of different bacteria play an important role for the host.

With the intake of large amounts of industrial food, the intestinal microbial diversity of captive Tibetan wild asses decreased, increasing the risk of disease. Other methods of feeding that better approximate nature should be chosen to protect rare and endangered wildlife in a captive environment. The gut microbiota of the Tibetan wild ass is complex and this study of its composition and function is of great significance to the protection of the Tibetan wild ass. In addition, it is important to conduct more research to understand how environmental differences directly affect the diversity of bacteria in stool samples.

Statement on the welfare of animals

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were approved by the Ethics and Welfare of Experiment Animals Committee affiliated to Northwest Institute of Plateau Biology.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We express our heartfelt thanks to the director of the Yellow‐River‐Sources Park Management Station at Three‐River‐Sources National Park in Maduo county and all breeders at the Qinghai‐Tibet plateau wild animal park in Xining for their active cooperation and their valuable suggestions on the collection of faecal samples. This study was financially supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2017YFC0506405); The Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA2002030302); Qinghai Key R&D and Transformation Program (2019‐SF‐150); Construction Fund for Qinghai Key Laboratories (2017‐ZJ‐Y23).

References

- Cani, P.D. (2018) Human gut microbiome: hopes, threats and promises. Gut 67, 1716–1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaner, O. , Goday, A. , Park, Y.M. , Lee, S.H. , Magkos, F. , Shiow, S.T.E. and Schroder, H. (2018) The gut microbiome profile in obesity: a systematic review. Int J Endocrinol 2018, 4095789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa, M.C. , Arroyo, L.G. , Allen‐Vercoe, E. , Stampfli, H.R. , Kim, P.T. , Sturgeon, A. and Weese, J.S. (2012) Comparison of the fecal microbiota of healthy horses and horses with colitis by high throughput sequencing of the V3‐V5 region of the 16S rRNA gene. PLoS ONE 7, e41484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, S. , Wu, X. , Liu, S. , Su, X. , Wu, Y. , Shi, J. , Li, X. , Zhang, X. et al (2015) Estimation of ecological carrying capacity for wild yak, kiang, and Tibetan antelope based on habitat suitability in the Aerjin Mountain Nature Reserve, China. Acta Ecol Sin 35, 7598–7607. [Google Scholar]

- Eckburg, P.B. , Bik, E.M. , Bernstein, C.N. , Purdom, E. , Dethlefsen, L. , Sargent, M. , Gill, S.R. , Nelson, K.E. et al (2005) Diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science 308, 1635–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y. , Zhang, H. , Gao, X. , Shang, S. , Wu, X. , Chen, J. , Zhang, W. , Zhang, W. et al (2016) Comparison of the bacterial communities in feces from wild versus housed sables (Martes zibellina) by high‐throughput sequence analysis of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene. AMB Express 6, 98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan, Y. , Yang, H. , Han, S. , Feng, L. , Wang, T. and Ge, J. (2017) Comparison of the gut microbiota composition between wild and captive sika deer (Cervus nippon hortulorum) from feces by high‐throughput sequencing. AMB Express 7, 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X. , Shao, Q. , Li, Y. , Wang, Y. , Wang, D. , Liu, J. , Fan, J. and Yang, F. (2018) Application of UAV remote sensing for a population census of large wild herbivores—taking the Headwater Region of the Yellow River as an Example. Remote Sens 10, 1041. [Google Scholar]

- He, X. , Marco, M.L. and Slupsky, C.M. (2013) Emerging aspects of food and nutrition on gut microbiota. J Agric Food Chem 61, 9559–9574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, M.Y. , Jang, H.M. and Kim, D.H. (2019) High‐fat diet causes psychiatric disorders in mice by increasing Proteobacteria population. Neurosci Lett 698, 51–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, L. and Bard‐Jorgen, B. (2005) Density of Tibetan antelope, Tibetan wild ass and Tibetan gazelle in relation to human presence across the Chang Tang Nature Reserve of Tibet, China. Acta Zool Sin 51, 586–597. [Google Scholar]

- Katsimichas, T. , Ohtani, T. , Motooka, D. , Tsukamoto, Y. , Kioka, H. , Nakamoto, K. , Konishi, S. , Chimura, M. et al (2018) Non‐Ischemic heart failure with reduced ejection fraction is associated with altered intestinal microbiota. Circ J 82, 1640–1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kefena, E. , Mekasha, Y. , Han, J.L. , Rosenbom, S. , Haile, A. , Dessie, T. and Beja‐Pereira, A. (2012) Discordances between morphological systematics and molecular taxonomy in the stem line of equids: a review of the case of taxonomy of genus Equus . Livestock Sci 143, 105–115. [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa, S. , Kishimoto, T. , Mizuno, S. , Masaoka, T. , Naganuma, M. , Liang, K.C. , Kitazawa, M. , Nakashima, M. et al (2018) The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhea and functional constipation: an open‐label observational study. J Affect Disord 235, 506–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ley, R.E. , Hamady, M. , Lozupone, C. , Turnbaugh, P.J. , Ramey, R.R. , Bircher, J.S. , Schlegel, M.L. , Tucker, T.A. et al (2008) Evolution of mammals and their gut microbes. Science 320, 1647–1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L. , Wan, Z. , Luo, T. , Fu, Z. and Jin, Y. (2018) Polystyrene microplastics induce gut microbiota dysbiosis and hepatic lipid metabolism disorder in mice. Sci Total Environ 631, 449–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig, W. , Euzéby, J. and Whitman, W.B. (2010) Taxonomic outlines of the phyla Bacteroidetes, Spirochaetes, Tenericutes (Mollicutes), Acidobacteria, Fibrobacteres, Fusobacteria, Dictyoglomi, Gemmatimonadetes, Lentisphaerae, Verrucomicrobia, Chlamydiae, and Planctomycetes In Bergey's Manual® of Systematic Bacteriology, 21–24. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Mariat, D. , Firmesse, O. , Levenez, F. , Guimaraes, V. , Sokol, H. , Dore, J. , Corthier, G. and Furet, J.P. (2009) The Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio of the human microbiota changes with age. BMC Microbiol 9, 123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelbos, I.S. , Vester Boler, B.M. , Qu, A. , White, B.A. , Swanson, K.S. and Fahey, G.C. Jr (2010) Phylogenetic characterization of fecal microbial communities of dogs fed diets with or without supplemental dietary fiber using 454 pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 5, e9768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moehlman, P.D.R. (2002) Equids: Zebras, Asses, and Horses: Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, X.C. , Tickle, T.L. , Sokol, H. , Gevers, D. , Devaney, K.L. , Ward, D.V. , Reyes, J.A. , Shah, S.A. et al (2012) Dysfunction of the intestinal microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease and treatment. Genome Biol 13, R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panebianco, C. , Andriulli, A. and Pazienza, V. (2018) Pharmacomicrobiomics: exploiting the drug‐microbiota interactions in anticancer therapies. Microbiome 6, 92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulikkan, J. , Maji, A. , Dhakan, D.B. , Saxena, R. , Mohan, B. , Anto, M.M. , Agarwal, N. , Grace, T. et al (2018) Gut microbial dysbiosis in indian children with autism spectrum disorders. Microb Ecol 76, 1102–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J. , Li, R. , Raes, J. , Arumugam, M. , Burgdorf, K.S. , Manichanh, C. , Nielsen, T. , Pons, N. et al (2010) A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature 464, 59–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J. , Li, Y. , Cai, Z. , Li, S. , Zhu, J. , Zhang, F. , Liang, S. , Zhang, W. et al (2012) A metagenome‐wide association study of gut microbiota in type 2 diabetes. Nature 490, 55–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C. , Gong, L. , Zhang, X. , Wang, Y. , Wang, Y. , Wang, B. , Li, Y. and Li, W. (2018) Effect of Saccharomyces boulardii and Bacillus subtilis B10 on gut microbiota modulation in broilers. Anim Nutr 4, 358–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quagliariello, A. , Del Chierico, F. , Russo, A. , Reddel, S. , Conte, G. , Lopetuso, L.R. , Ianiro, G. , Dallapiccola, B. et al (2018) Gut microbiota profiling and gut–brain crosstalk in children affected by pediatric acute‐onset neuropsychiatric syndrome and pediatric autoimmune neuropsychiatric disorders associated with streptococcal infections. Front Microbiol 9, 675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley, E.M. (2010) Prebiotics and probiotics; modifying and mining the microbiota. Pharmacol Res 61, 213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roche‐Lima, A. , Carrasquillo‐Carrion, K. , Gómez‐Moreno, R. , Cruz, J.M. , Velazquez‐Morales, D. , Rogozin, I.B. and Baerga‐Ortiz, A. (2018) The presence of genotoxic and/or pro‐inflammatory bacterial genes in gut metagenomic databases and their possible link with inflammatory bowel diseases. Front Genet 9, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnenburg, E.D. , Smits, S.A. , Tikhonov, M. , Higginbottom, S.K. , Wingreen, N.S. and Sonnenburg, J.L. (2016) Diet‐induced extinctions in the gut microbiota compound over generations. Nature 529, 212–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St‐Louis, A. and Côté, S.D. (2009) Equus kiang (Perissodactyla: Equidae). Mammalian Species 304, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, M.F. and Shen, Y.Q. (2018) Dysbiosis of gut microbiota and microbial metabolites in Parkinson's disease. Ageing Res Rev 45, 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Abbeele, P. , Grootaert, C. , Marzorati, M. , Possemiers, S. , Verstraete, W. , Gerard, P. , Rabot, S. , Bruneau, A. et al (2010) Microbial community development in a dynamic gut model is reproducible, colon region specific, and selective for Bacteroidetes and Clostridium cluster IX. Appl Environ Microbiol 76, 5237–5246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.S. and Yi, G.X. (2000) Status of wild ass in China. Chinese Biodiversity 8, 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X. , Zhang, H. , Chen, J. , Shang, S. , Wei, Q. , Yan, J. and Tu, X. (2016) Comparison of the fecal microbiota of dholes high‐throughput Illumina sequencing of the V3‐V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 100, 3577–3586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xenoulis, P.G. , Gray, P.L. , Brightsmith, D. , Palculict, B. , Hoppes, S. , Steiner, J.M. , Tizard, I. and Suchodolski, J.S. (2010) Molecular characterization of the cloacal microbiota of wild and captive parrots. Vet Microbiol 146, 320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yifan, C. and Jianping, S. (2006) A new technique for temporary slide mounting inmicroh istological herbivore fecal analysis. Acta Theriologica S inica 26, 407–410. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, B. , Huai, H. , Zhang, Y. , Le, Z. and Wei, W. (2007) Trophic niches of Pantholops hodgsoni, Procapra picticaudata and Equus kiang in Kekexili region. J Appl Ecol 18, 766–770. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, J. , Han, H. , Li, Y. , Liu, Z. , Zhao, Y. , Fang, R. , Huang, X. , Zheng, J. et al (2017) Lysine restriction affects feed intake and amino acid metabolism via gut microbiome in piglets. Cell Physiol Biochem 44, 1749–1761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun, D. , Qi, W. , Yibo, H. , Xiao, W. , Yonggang, N. , Xiaoping, W. and Fuwen, W. (2017) Advance and prospects of gut microbiome in wild mammals. Acta Theriologica Sinica 37, 399–406. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C. , Zhang, M. , Pang, X. , Zhao, Y. , Wang, L. and Zhao, L. (2012) Structural resilience of the gut microbiota in adult mice under high‐fat dietary perturbations. ISME J 6, 1848–1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z. , Xu, D. , Wang, L. , Hao, J. , Wang, J. , Zhou, X. , Wang, W. , Qiu, Q. et al (2016) Convergent evolution of rumen microbiomes in high‐altitude mammals. Curr Biol 26, 1873–1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N. , Ju, Z. and Zuo, T. (2018) Time for food: the impact of diet on gut microbiota and human health. Nutrition 51–52, 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, L. , Zhang, F. , Ding, X. , Wu, G. , Lam, Y.Y. , Wang, X. , Fu, H. , Xue, X. et al (2018) Gut bacteria selectively promoted by dietary fibers alleviate type 2 diabetes. Science 359, 1151–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L. , Wu, Q. , Dai, J. , Zhang, S. and Wei, F. (2011) Evidence of cellulose metabolism by the giant panda gut microbiome. Proc Natl Acad Sci 108, 17714–17719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitvogel, L. , Ma, Y. , Raoult, D. , Kroemer, G. and Gajewski, T.F. (2018) The microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies. Science 359, 1366–1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]