Abstract

BACKGROUND

Willingness to donate blood depends on personal characteristics, beliefs, and motivations, but also on the cultural context. The aim of this study was to examine whether willingness to donate blood is associated with attitudes toward blood transfusion, personal motivators, and incentives and whether these factors vary across countries in the European Union (EU).

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS

The sample consisted of 27,868 participants, from 28 EU member states, who were interviewed about blood donation and transfusion‐related issues for the 2014 round of the Eurobarometer, a country‐comparative survey, collected on behalf of the European Commission. Participants were asked whether they would be willing to donate blood and for which reasons (motivators) and which incentives are appropriate to receive in return for a blood donation.

RESULTS

Willingness to donate varied significantly across countries and was positively associated with perceived blood transfusion safety. Furthermore, helping family or people in need were the most powerful motivators for blood donation willingness in almost all countries. In contrast, the number of participants who were willing to donate to alleviate shortages or to contribute to research varied widely across countries. The wish to receive certain incentives, however, did not seem to be related to willingness to donate.

CONCLUSION

Perceived blood transfusion safety and personal motivations may be stronger determinants of willingness to donate than receiving certain incentives. EU‐wide strategies and guidelines for donor recruitment and retention should take both overall and country‐specific patterns into account. For example, education on the importance of donation could be considered.

ABBREVIATIONS

- EU

European Union

- HDI

Human Development Index

The donation of substances of human origin (SoHo), such as blood, are of utmost importance for maintaining health care. The availability of these human substances completely depends on voluntary donors. It is crucial that a country's donor pool is sufficient enough to ensure access to every needed blood, cell, or organ type. Patient needs for specific blood products (e.g., from ethnic minority donors) are changing due to population aging, migration flows, population profiles, and patient blood management.1 However, shortage, supply, and self‐sufficiency vary widely across the European Union (EU) and United States, as does the profile of the donors and patients.2, 3, 4 A recent publication gave an overview of important demographic characteristics of those participants with a donation history in the current EU context.5 However, new donors, especially those with specific characteristics (e.g., male, ethnic minority), will have to be recruited to safeguard a timely, sufficient, and matching blood supply and respond to the increasing demand for specific blood and plasma products. Knowledge about possible future donors, who are at the moment potentially willing to donate and why, may contribute to the development of new and more targeted recruitment strategies.

Both the World Health Organization and the European Commission agree that voluntary, nonremunerated donations would be ideal.6, 7 The evidence pointing toward the conclusion that receiving cash at least does not improve donation behavior (in the long run) is affirmative; however, how noncash items or health screenings influence donor behavior is still under debate.8, 9, 10 A recent systematic review found that attitudes toward incentives are mixed and depend on age, donor experience, and the donation reward system of the country of residence.11

In contrast to external motivators, willingness to donate may depend more on personal characteristics, on beliefs and motivations,12 and on cultural and economic context of the country individuals live in.13, 14, 15 Earlier studies have investigated demographic characteristics, individual attitudes, and motivations in association with (potential) donor behavior.16, 17, 18, 19, 20 Several motivational mechanisms have been identified, among which awareness of need is important in explaining prosocial and giving behavior.21, 22, 23 Awareness of need is a central giving mechanism that also applies to blood donor behavior24 and might therefore be associated with donation willingness especially for those who experienced a family member being ill and suffer(ed) from illnesses that require a blood transfusion. On a country level, factors such as the Human Development Index (HDI; a composite statistic of a nation's health) have been shown to be a predictor of donation safety perception25 and the number of donors and collected blood units in a country.13

An empirical examination whether certain individual demographic and attitudinal factors are universal or contextual determinants of willingness to donate blood in the future, especially across countries, has been missing so far. Such an outlook toward possible future donors, who have yet to be convinced to take the step to actually donate, and reasons why they would consider doing so or not, can make a considerable contribution to a future road map of donor recruitment. The aim of this study was therefore to examine whether willingness to donate blood is associated with demographic variables; attitudes; and personal motivators, incentives, and concerns and more importantly whether these factors vary across countries in Europe. We examined whether a country's performance in terms of health, education and income, indicated by the HDI (i.e., a long and healthy life), education (i.e., access to knowledge), and income (i.e., a decent standard of living) can explain part of the variation in individual willingness to donate across European countries. Moreover, we assessed which personal barriers, incentives, and motivators are indicative of future willingness to donate and potentially effective targets for future recruitment purposes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants and procedure

The data stem from the publicly available dataset of the 2014 round of the Eurobarometer (82.2, Special Eurobarometer 426), a repeated cross‐sectional survey among EU Member States, carried out by TNS Opinion, at the request of the European Commission. The Eurobarometer is conducted in the majority of European countries. Each survey consists of approximately 1000 face‐to‐face interviews in every country. For each country, a comparison between sample composition and a universe description is carried out. This universe description is made available by National Survey Research Institutes and/or EUROSTAT. The data cover the resident population of the respective countries, aged 15 years or older and having sufficient command of the national languages. The sample design applied is a multistage, random (probability) one.26 The sample consisted of 27,868 participants from 28 EU member states, who were interviewed about blood, cell, and tissue donation and transfusion‐related issues. The European Commission approved the study protocols, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Dependent variables

Donation willingness (and history)

Participants were asked about donation willingness and history with the following question: “During the lifetime of a person it is possible to donate different body substances (blood or cells) to help other people. Could you please indicate which ones you have or would be prepared to donate yourself?” The participants rated their history and willingness for donating blood as well as several other types of substances (e.g., plasma, marrow) separately, by marking one of the following five options: “Yes, I have donated in the past and I would be prepared to donate in the future”; “Yes, I have donated in the past but I would not be prepared to donate in the future”; “No, I have not donated in the past but I would be prepared to donate in the future”; “No, I have not donated in the past and I would not be prepared to donate in the future”; or “I don't know.” Participants who answered “I don't know” to the blood donation item where excluded from the analyses. The dependent variable was consequently defined as “willing to donate” (yes/no).

Independent variables

Demographics

Demographic variables included sex, age (in years), the number of years someone had followed an education (participants were asked their age when they stopped after education), employment status (employed versus unemployed), marital status (partner versus single), and parent status (no children versus any children). A proxy of financial health was estimated with the item “How often do you have problems with paying the bills?” (almost never/never, from time to time, most of the time, or a refusal to answer). In addition, participants were asked if they lived in a rural area or village, a small or middle sized town, or a large town.

Country‐level predictor

Because blood donation willingness has been linked to education, income, and health on the individual level (cf. Piersma et al.12 for an overview), we consider an index referring to a country's performance regarding these indicators. We use the United Nation Development Programme (UNDP) HDI, which reflects factors such as a long and healthy life, education (i.e., access to knowledge), and income (i.e., a decent standard of living). The health component is assessed by life expectancy at birth using a minimum value of 20 years and maximum value of 85 years. The education dimension is measured by years of schooling for adults aged 25 years and expected years of schooling for children of school entering age. The standard of living dimension is measured by gross national income per capita.27 Due to its composite nature, the HDI reflects both a country's economic as well as human development. The HDI ranges from 0.794 in Bulgaria to 0.926 in Germany.

Transfusion‐related factors and beliefs

Participants were asked if they would or would not accept a blood transfusion themselves “if they personally had a medical need.” In addition, participants rated to what extent they thought receiving a blood transfusion is safe by asking: “As far as you know, do you think that blood transfusion is safe for recipients in your country?” (on a four point scale from “No, definitely not” to “Yes, definitely” or “do not know”). Finally, participants indicated whether they “know someone who has received blood.

Donation incentives

Furthermore, participants were asked on a yes/no basis: “For donating blood or plasma during someone's lifetime, do you consider it acceptable to receive …”: “refreshments (e.g. coffee, soft drinks, snacks),” “a free physical checkup (e.g., blood pressure, pulse, body temperature),” “free testing,” “free medical treatments,” “noncash items (e.g., first aid kits),” “reimbursement of travel costs,” and “cash amounts additional to the reimbursement of the costs related to the donation, time off work (for the time needed for the donation and/ or recovery).”

Donation concerns

participants were asked: “Which of the following concerns would you have if you were treated with donated blood, cells, or tissues?” and replied yes or no to “It is against my religion”, “Complications as a result of the medical procedure,” “the risk of contracting a disease (e.g., HIV, hepatitis),” “A lack of effectiveness of the treatment,” “Medical errors (e.g., being administered the wrong blood type),” “Receiving a donation from a paid donor,” “Receiving a donation from another EU Member State,” and “Receiving a donation from a country outside the EU.”

Donation motivators

Only participants who indicated that they were prepared to donate any body substances were asked about the reasons with the following question: “For which of the following reasons have you or would you donate any of the body substances mentioned earlier?” Multiple answers were allowed. The answers were recoded 0 “yes” or 1 “no” for each of the following options: “To help a family member, relative, or friend”; “To help other people in need”; “To alleviate shortages of these substances”; “To support medical research”; and “To receive something in return for you or your relatives.”

Statistical analyses

First, 2.8% of the participants refused to answer the dependent variable question on blood donation history and willingness and were excluded from the sample. Second, as we are interested in participants who are currently or soon eligible to donate, we selected respondents ranging in age between 15 and 70 years and excluded an additional 17.5% of the sample with an age of 70 years and older. The analyses were run on the resulting sample of n = 22,348.

Multilevel modeling

When participants are “nested” within a country and where the predictors are both on the individual level (e.g., age) and on the country level (e.g., HDI), it is important to use multilevel logistic regression modeling. First, an “empty” model (without any predictors) was estimated in which only the differences in donation willingness between the countries is assessed. Second, this model was extended by adding the country level and demographic variables (Model 1). Then transfusion related factors were added (Model 2). Finally, the incentives or concerns were added. Changes in model fit indices (AICC) of consecutive models were compared to assess whether adding the extra predictors significantly improved the model fit, with the aim of finding the best fitting but most parsimonious model. Significance of the random intercepts was tested with a Wald Z test. These analyses were run separately for participants with (donors) and without blood donation history (nondonors).

Country‐level variation

To assess country‐level differences, logistic regression analyses were run to examine the effect of transfusion related factors and incentives on donation willingness, controlled for demographic variables. To compare proportions or yes/no answers by donor status, chi‐square statistics were run per country. Both analyses were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni method, resulting in a p value for significance of p < 0.001.

RESULTS

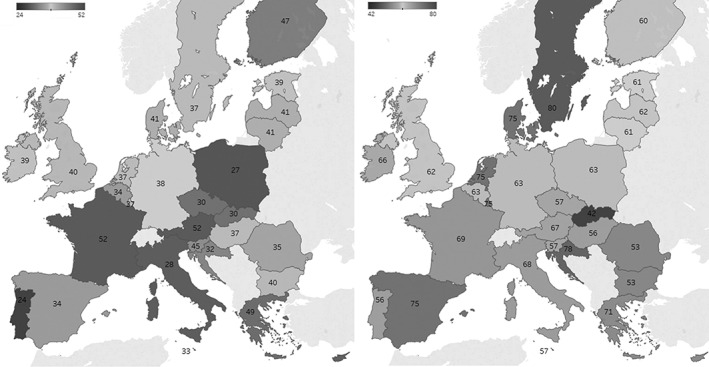

Overall, 37.9% (n = 8471) of all included participants had ever donated blood (see Fig. 1), of whom 6434 (76%) would be willing to do so again. Of the 13,877 who had no previous history of blood donation, 7814 (56.3%) would be prepared to donate in the future. There was significant variance in blood donation willingness across EU member states as shown by the random intercepts of the “empty” models for both nondonors (variance, 0.228; SD, 0.065; Wald Z, 3.523; p < 0.001) and donors (variance, 0.102; SD, 0.033; Wald Z, 3.084; p = 0.002). The number of people who indicated to be willing to donate in the future ranged from 41.9% in Slovakia to as high as 80.1% in Sweden (see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Percentage of participants of EU member states with a history of blood donation (left) or willing to donate blood in the future (right).

Demographic and transfusion‐related variables

Table 1 shows the full multilevel models for nondonors and donors separately. Regardless of (previous) donor status, it was found that male, younger, and employed participants were more willing to donate. Whether people lived rurally or in more urban areas was unrelated to willingness in both groups. However, financially healthy nondonors with more years of education were more likely to be willing to donate in the future compared to nondonors with lower socioeconomic status, whereas no such differences were found in the donor group. In general, current donors were more likely to live in a country with a higher HDI. For family indicators it was found that donors with a partner and children were more willing to donate in the future, while this was not the case for nondonors.

Table 1.

Individual‐ and country‐level predictors of blood donation willingness stratified by previous donor experience

| Fixed factors | Nondonors | Donors | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | OR | 95% CI | p value | B | SE | OR | 95% CI | p value | |

| Intercept | −2.807 | 1.809 | −1.890 | 1.242 | ||||||

| Model 1 | ||||||||||

| HDI | 2.301 | 2.071 | 9.987 | 0.172‐578.737 | 0.267 | 3.790 | 1.291 | 44.250 | 3.523‐555.823 | 0.003* |

| Sex (male) | 0.114 | 0.046 | 1.120 | 1.024‐1.226 | 0.013* | 0.152 | 0.060 | 1.164 | 1.034‐1.311 | 0.012* |

| Age | −0.035 | 0.002 | 0.966 | 0.962‐0.970 | 0.000* | −0.040 | 0.003 | 0.960 | 0.954‐0.966 | <0.001* |

| Years of education | 0.016 | 0.005 | 1.016 | 1.007‐1.025 | 0.001* | 0.010 | 0.008 | 1.010 | 0.994‐1.026 | 0.210 |

| Difficulty paying bills: never | 0.236 | 0.086 | 1.266 | 1.070‐1.498 | 0.006* | 0.094 | 0.118 | 1.098 | 0.872‐1.383 | 0.426 |

| Difficulty paying bills: sometimes | 0.167 | 0.092 | 1.182 | 0.987‐1.414 | 0.068 | 0.131 | 0.146 | 1.140 | 0.857‐1.517 | 0.368 |

| Employed | 0.164 | 0.045 | 1.178 | 1.078‐1.288 | <0.001* | 0.270 | 0.057 | 1.310 | 1.172‐1.465 | 0.000* |

| Having a partner | 0.061 | 0.044 | 1.063 | 0.974‐1.159 | 0.171 | 0.113 | 0.047 | 1.120 | 1.021‐1.229 | 0.016* |

| Having a child | 0.069 | 0.045 | 1.071 | 0.980‐1.171 | 0.129 | 0.230 | 0.075 | 1.259 | 1.088‐1.457 | 0.002* |

| Living in a rural area | −0.043 | 0.077 | 0.958 | 0.823‐1.115 | 0.582 | −0.150 | 0.093 | 0.861 | 0.717‐1.034 | 0.109 |

| Living in a town | −0.038 | 0.076 | 0.963 | 0.829‐1.118 | 0.621 | −0.016 | 0.084 | 0.984 | 0.834‐1.160 | 0.844 |

| Model 2: transfusion‐related factors | ||||||||||

| Accepts treatment with blood | 1.118 | 0.056 | 3.060 | 2.741‐3.417 | <0.001* | 0.252 | 0.092 | 1.287 | 1.075‐1.540 | 0.006* |

| Perceives transfusion as safe | 0.337 | 0.031 | 1.401 | 1.319‐1.489 | <0.001* | 0.217 | 0.035 | 1.242 | 1.161‐1.330 | <0.001* |

| Knows recipient of blood | 0.107 | 0.052 | 1.113 | 1.005‐1.233 | 0.041* | 0.265 | 0.055 | 1.303 | 1.169‐1.452 | <0.001* |

| Random factors | ||||||||||

| Change in AICC (change in df)† | 2489.9 | (3) | p value | 1196.5 | (3) | p value | ||||

| Variance (intercept) | 0.228 | 0.065 | <0.001 | 0.102 | 0.033 | 0.002 | ||||

| Wald Z | 3.523 | 3.084 | ||||||||

p < 0.05.

Model 2 compared to Model 1.

In both groups a strong and positive relationship was found between the willingness to donate and positive beliefs about blood transfusion safety, the willingness to accept a blood transfusion, and having an acquaintance who ever needed a blood transfusion (see Table 2 for an overview per country).

Table 2.

Reported mean or percentage of the blood transfusion factors and their relationship (OR) to donation willingness

| Country | Willing to accept a transfusion | Perceived transfusion safety | Knows a transfusion recipient | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent | OR | Mean | SD | OR | Percent | OR | |

| Sweden | 95.9 | 1.61 | 3.64 | 0.54 | 1.22 | 56.9 | 0.84 |

| Denmark | 95.4 | 3.23 | 3.75 | 0.49 | 1.03 | 57.4 | 1.04 |

| The Netherlands | 92.9 | 3.21* | 3.65 | 0.52 | 1.42 | 46.1 | 1.00 |

| Luxembourg | 91.0 | 4.40* | 3.18 | 0.81 | 1.00 | 47.0 | 1.04 |

| Spain | 90.3 | 3.62* | 3.62 | 0.60 | 1.32 | 46.6 | 1.17 |

| Finland | 88.4 | 1.88 | 3.76 | 0.49 | 1.26 | 52.4 | 1.51 |

| France | 88.4 | 2.97* | 2.88 | 0.91 | 1.21 | 39.9 | 0.76 |

| Greece | 86.4 | 2.30* | 3.25 | 0.74 | 1.27 | 72.7 | 1.40 |

| Ireland | 85.0 | 3.02* | 3.47 | 0.67 | 1.11 | 53.9 | 1.16 |

| Belgium | 83.4 | 4.09* | 3.18 | 0.90 | 1.56* | 47.4 | 1.27 |

| Malta | 83.2 | 1.11 | 3.64 | 0.65 | 1.25 | 52.1 | 1.53 |

| Cyprus | 82.2 | 1.96 | 3.23 | 0.79 | 1.30 | 63.7 | 1.51 |

| United Kingdom | 81.9 | 1.92* | 3.59 | 0.62 | 1.25 | 38.5 | 1.20 |

| Slovenia | 81.8 | 2.27* | 3.61 | 0.55 | 1.27 | 46.7 | 1.05 |

| Czech Republic | 80.3 | 2.70* | 3.41 | 0.72 | 1.42 | 53.5 | 1.24 |

| Lithuania | 79.7 | 2.98* | 3.11 | 0.79 | 1.16 | 39.0 | 0.81 |

| Latvia | 79.2 | 1.38 | 2.98 | 0.79 | 1.43* | 50.7 | 1.24 |

| Germany | 78.2 | 2.77* | 3.28 | 0.76 | 1.60* | 35.6 | 1.34 |

| Slovakia | 76.7 | 2.64* | 3.14 | 0.80 | 1.30 | 60.7 | 0.93 |

| Croatia | 76.1 | 2.61* | 3.29 | 0.79 | 1.34 | 53.2 | 1.68 |

| Hungary | 72.4 | 2.07* | 3.05 | 0.93 | 1.51* | 43.4 | 1.51 |

| Austria | 72.2 | 2.27* | 3.29 | 0.75 | 1.32 | 40.1 | 1.87* |

| Estonia | 70.9 | 1.96 | 3.34 | 0.83 | 1.67* | 44.3 | 1.12 |

| Portugal | 67.1 | 2.76* | 3.17 | 0.78 | 1.41 | 39.9 | 1.72 |

| Italy | 66.4 | 3.18* | 2.85 | 0.76 | 1.59* | 44.9 | 0.77 |

| Poland | 63.4 | 2.31* | 3.09 | 0.72 | 1.65* | 36.4 | 0.99 |

| Bulgaria | 62.0 | 1.97* | 2.73 | 0.91 | 1.69* | 53.9 | 1.20 |

| Romania | 59.2 | 2.03* | 2.79 | 0.90 | 1.28 | 32.4 | 1.15 |

| Min | 59.2 | 2.73 | 32.4 | ||||

| Max | 95.9 | 3.76 | 72.7 | ||||

| Average | 79.6 | 3.28 | 48.2 | ||||

p < 0.001.

Concerns

Adding the concerns with regards to blood transfusions did not improve the model fit, indicating that concerns about blood transfusions were not directly linked to blood donation willingness. Table S1 in the supplementary materials (available as supporting information in the online version of this paper) shows the percentage of participants who answered yes to each of the concerns per country. Fear of contracting a disease was on average the most commonly mentioned concern (58%), followed by worries about medical complications (48%) or errors (44%). Religious concerns were uncommon (1.8%).

However, as perceived blood transfusion safety is a strong predictor of willingness, we assessed the relationship between blood transfusion concerns and perceived blood transfusion safety. Regardless of donor experience, participants with religious concerns, concerns about contracting a disease, or medical errors perceived blood transfusions to be less safe, whereas concerns about medical complications or receiving blood from a non‐EU donor were related to a higher perceived transfusion safety (for the exact statistics of these analyses, we refer to Table S2 in the supplementary material).

Incentives

For donors, no significant relationships between the reported appropriateness of incentives and willingness to donate were found. In contrast, nondonors who indicated that a medical checkup would be an appropriate incentive were more willing to donate (B = 0.219; OR (95% CI), 1.244 (1.094‐1.415); p = 0.001). Interestingly, in the nondonor group we found that people who indicated that receiving cash was an acceptable reward for donating blood were actually less likely to be willing to donate blood (B = −0.208; OR (95% CI), 0.813 (0.698‐0.946); p = 0.008). However, adding these incentives to the Model 2 presented in Table 1 worsened model fit for both donors and nondonors, indicating that they do not significantly contribute to the explained variance in donation willingness. In additional analyses (presented in the Table S3) we examined the percentage of participants per country who find each incentive appropriate and the extent to which this predicted donation willingness in each country, using logistic regressions. Even though the majority of the participants in all countries reported a positive attitude toward receiving cash, this was not related to willingness to donate. Generally, most incentives do not seem to be strongly related to willingness to donate in most countries, with a few exceptions. Potential donors in Germany and Belgium have strong positive attitudes toward refreshments, Swedes might prefer time off work, Fins a medical checkup, and the Portuguese medical treatments.

Personal motivators

Finally, we assessed which personal motivators were mentioned most often by those willing to donate in the future, and this was the same for donors and nondonors (see Table 3). By far most participants agree they would donate to help friends and family, which was indicated more often by nondonors (82%) than donors (77%) on average, especially in the Netherlands, Portugal, and Slovakia. Only 57% of the Austrian nondonors, however, agreed with this statement. Secondly, 73% of non‐donors and 76% of donors on average agreed that they would donate to help others in need.

Table 3.

Percentage of nondonors and donors who indicated agreement with the personal motivators

| Percent yes | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Number | To help family or friends | To help others | To alleviate shortages | To support medical research | To receive something in return | |||||

| Nondonors | Donors | Nondonors | Donors | Nondonors | Donors | Nondonors | Donors | Nondonors | Donors | ||

| France | 539 | 89 | 88 | 77 | 76 | 43 | 54 | 48 | 55 | 4 | 3 |

| Belgium | 496 | 83 | 76 | 77 | 78 | 41* | 56* | 44 | 43 | 8 | 8 |

| The Netherlands | 623 | 85* | 71* | 82 | 82 | 45* | 63* | 48 | 57 | 8 | 7 |

| Germany | 757 | 80 | 74 | 83 | 83 | 32 | 37 | 26 | 25 | 4 | 2 |

| Italy | 585 | 75 | 72 | 71 | 76 | 20 | 23 | 25 | 25 | 1 | 2 |

| Luxembourg | 318 | 98 | 94 | 83 | 76 | 43 | 47 | 45 | 43 | 8 | 2 |

| Denmark | 569 | 85 | 78 | 89 | 85 | 68 | 72 | 64 | 62 | 12 | 10 |

| Ireland | 534 | 83 | 86 | 73 | 77 | 38 | 47 | 42 | 45 | 9 | 15 |

| United Kingdom | 639 | 84 | 78 | 73 | 81 | 34 | 42 | 36 | 40 | 8 | 9 |

| Greece | 611 | 84 | 79 | 80 | 81 | 22 | 24 | 13 | 16 | 5 | 3 |

| Spain | 599 | 77 | 73 | 78 | 88 | 31* | 47* | 37* | 50* | 5 | 8 |

| Portugal | 457 | 78* | 63* | 81 | 83 | 22 | 24 | 31 | 29 | 6 | 3 |

| Finland | 437 | 82 | 77 | 80 | 83 | 37 | 44 | 48 | 50 | 15 | 16 |

| Sweden | 601 | 89 | 87 | 87 | 90 | 62 | 71 | 68 | 75 | 10 | 12 |

| Austria | 537 | 57 | 69 | 68 | 78 | 35* | 52* | 27 | 39 | 5 | 6 |

| Cyprus (Republic) | 286 | 84 | 79 | 82 | 88 | 30 | 28 | 20 | 22 | 5 | 0 |

| Czech Republic | 521 | 91 | 88 | 57 | 62 | 23 | 29 | 22 | 29 | 14 | 17 |

| Estonia | 429 | 83 | 79 | 66 | 73 | 24 | 32 | 25 | 32 | 5 | 12 |

| Hungary | 485 | 71 | 69 | 65 | 74 | 23 | 26 | 21 | 28 | 10 | 9 |

| Latvia | 562 | 87 | 77 | 61 | 66 | 11* | 23* | 11 | 13 | 7 | 9 |

| Lithuania | 458 | 85 | 80 | 62 | 72 | 16 | 22 | 11 | 10 | 3 | 7 |

| Malta | 218 | 78 | 65 | 78 | 80 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 32 | 9 | 8 |

| Poland | 538 | 74 | 64 | 74 | 77 | 17 | 18 | 9 | 13 | 5 | 5 |

| Slovakia | 364 | 90* | 77* | 61 | 66 | 15 | 18 | 15 | 17 | 21 | 13 |

| Slovenia | 452 | 91 | 86 | 69 | 69 | 26 | 33 | 30 | 33 | 9 | 11 |

| Bulgaria | 441 | 86 | 79 | 52 | 60 | 13 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 7 | 9 |

| Romania | 467 | 82 | 79 | 68 | 59 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 14 | 4 | 8 |

| Croatia | 725 | 78 | 79 | 71 | 76 | 23 | 25 | 16 | 25 | 3 | 4 |

| Min | 57 | 63 | 52 | 59 | 11 | 12 | 3 | 8 | 1 | 0 | |

| Max | 98 | 94 | 89 | 90 | 68 | 72 | 68 | 75 | 21 | 17 | |

| Average | 82 | 77 | 73 | 76 | 30 | 36 | 29 | 33 | 8 | 8 | |

p < 0.001.

The variance in the number of participants who reported they would be motivated by “alleviating shortages” was fairly high, with 11% to 68% of the nondonors (average, 30%) and 12% to 72% (average, 36%) of donors agreeing to this statement. Existing donors were more likely to agree with this motivator in Belgium, the Netherlands, Spain, and Austria. This motivator was especially unpopular, with less than 20% of nondonors agreeing, in Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, and Slovakia.

Similarly, donating to support medical research was not enough motivation for most participants, with 29% (3%‐68%) of nondonors and 33% (8%‐75%) of donors agreeing to this statement. Only in Sweden and Denmark more than 50% of participants would be motivated to donate for this reason. Finally, most participants (on average 92% in both groups) agreed that they would not be motivated to donate by receiving something in return.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to examine whether willingness to donate blood varies across Europe and, if so, explain this variation with individual‐ and country‐level factors. Considerable variation across European countries exists with regard to individual blood donation willingness and number of people who have ever given blood. Noticeably, more than 60% of the participants in most EU countries are willing to donate in the future, except in Portugal, Malta, the Czech‐Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, and countries in the Balkan region. Positively, the number of participants who indicated a willingness to donate is overall significantly higher than the number of people who ever donated in the past, showing that there are indeed pools of unexperienced but potential donors across the EU.

Becoming a blood donor is a personal decision influenced by individual and network characteristics. In the current sample, potential but unexperienced donors were most likely young men, with good education levels and financial health. Given the changing demographics of both general and patient populations,28 young men are sought after as donors, as they can donate more often than women. However, the reported lack of representation of younger, single people in the donor population, for example, in the Netherlands,29 highlights the need for more tailored recruitment strategies and channels able to reach this population, such as social media.30 Participants with a history of blood donation and with a partner and or children were also more likely to be willing to donate, which could be an indication that partnership and parenthood enhance people's feelings of social responsibility that may extend toward altruistic behavior directed to society. The evidence to date of the relationship between personal characteristics and donor status and willingness is conflicted5, 18, 29, 31 (for a recent review see Piersma et al.12) and as such the current study and the Eurobarometer data set in general provide an interesting, large‐scale addition to this literature. The fact that HDI only predicted donation willingness in (former) donors supports the previously reported finding that HDI alone does not explain differences between countries regarding whole blood collections.13 However, this finding may be specific to the EU, as both the number of voluntary blood donations (compared to paid donations) and the availability of blood were positively related to gross national income in another study.32

For the development of effective and personalized recruitment strategies, it is important to focus on factors, both motivators and certainly also demotivators (cf. Merz et al.33), which can be targeted for change in contrast to factors such as sex and age. The general public perceptions about the transfusion chain as a whole, from donor to patient, is a good example. The results of the current study show these perceptions can be improved25 and that negative views of blood transfusion safety from the recipient point of view impact their donation willingness. Especially concerns about the possibility of contracting a disease or being the victim of a medical error during a transfusion were prevalent and strong negative predictors of perceived transfusion safety. Hence, improved education strategies to increase general trust in blood donation and blood transfusion, through interventions or campaigns, could be a way to motivate people to become a blood donor, especially for those countries where trust in the blood transfusion chain is low.

Even though noncash items or “gifts” seem an acceptable alternative and monetary incentives could relief shortages temporarily,9, 34, 35, 36, 37 the results of this study cannot corroborate this line of reasoning. Potential willingness to donate was either not or negatively related to positive attitudes toward receiving cash. Additionally, the number of participants who explicitly indicated that they would be motivated by cash was very low across all countries. However, attitudes to incentives were in a limited and varying way related to willingness, adding to the reported conflicted reports in the literature with regard to which incentives might work best to strengthen donor recruitment or retention.11 In the future, we recommend using alternative or experimental ways to study the effect of implicit and explicit motivations and incentives. For example, in a recent, multinational study (in preparation), we used a combination of questionnaires and a dictator game, in which participants chose to keep, give, or donate €10 received from donation or other sources38, 39 to study altruism and philanthropic activity.

Furthermore, the most commonly named motivator especially among nondonors is “to help family or friends”; however, the recipient is unknown in the current European systems. People who describe their willingness to donate based on motivations such as wanting to help family or others in need confirms earlier work that identified altruistic values16 and awareness of need as central motivators for health philanthropic behaviour such as blood donation.22, 24 In contrast, current (or previous) donors were more likely than nondonors to indicate that they would donate to alleviate shortages, which could reflect a better familiarity with the need for blood in this group. Awareness is higher in those who know a transfusion recipient, which indeed increased donation willingness as predicted based on the mechanism explaining prosocial and giving behavior.21, 22, 23

Knowledge of factors that foster a higher willingness to donate as well as about the contextual nature of these factors increases understanding of how people think and feel about blood donation. The current study explored an issue that received only limited attention thus far: donation willingness in a comparative perspective. To investigate variation across countries, one needs microlevel data about perceived willingness to donate from individuals across various countries, enriched with potentially important macrolevel factors. The Eurobarometer data is one of the few surveys that offer this opportunity. These strengths noted, this study is not without limitations. First, the Eurobarometer is a survey with relatively small sample sizes. The number of respondents per country is limited, and a meaningful “zooming in” on specific interesting groups of countries requires larger and more detailed data sets. More comprehensive information on whether a participant was, or would be, a donor at a public or private blood donation center would provide additional data to explain future donor behavior, as several EU countries provide both options. Second, recall bias and social desirability is a common bias in survey research and might especially occur with questions about prosocial behavior such as blood donation.5, 16 Still, in absence of other data sources, and while relying on register data, enriched with more in‐depth data on subjective attitudes and perception, we present a first step toward shedding light on differences in donor motivation and behavior across Europe.

In conclusion, the totality of the presented theory and data suggest that the willingness to donate blood varies strongly across social categories within and across countries in Europe. This study is a first attempt to examine the complex interplay between individual and context factors in shaping donation willingness across Europe. Given the importance of public risk perception to policy making and shaping public agendas, work detailing when universal and when country‐specific mechanisms determine blood (and other human substance) donation willingness, is a key agenda for health scientists and policy makers. It is recommended that educational and recruitment intervention strategies focus on increasing the perceived safety of the blood donor and recipient transfusion chain and increased awareness of the shortages in the blood supply, rather than on donation incentives.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. Percentage of participants who indicated agreement with the statements regarding transfusion concerns.

Table S2. Perceived Transfusion Safety as Predicted by Concerns of Non‐Donors and Donors.

Table S3. Percentage of participants who find incentives appropriate, and whether this predicted donation willingness, using logistic regressions

REFERENCES

- 1. Greinacher A, Weitmann K, Lebsa A, et al. A population‐based longitudinal study on the implications of demographics on future blood supply. Transfusion 2016;56:2986‐94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. C‐C/EAHC‐EU, Commission‐EU . An EU‐wide overview of the market of blood, blood components and plasma derivatives focusing on their availability for patients In: Creative Ceutical report revised by the commission to include stakeholders' comments; 2015. Brussels: European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Meier‐Kriesche HU, Port FK, Ojo AO, et al. Effect of waiting time on renal transplant outcome. Kidney Int 2000;58:1311‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. World Health Organisation . Blood safety and availability. 2017 [cited 2018 November 29], Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs279/en/.

- 5. Wittock N, Hustinx L, Bracke P, et al. Who donates? Cross‐country and periodical variation in blood donor demographics in Europe between 1994 and 2014. Transfusion 2017;57:2619‐28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. European Parliament . Directive 2002/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 27 January 2003 setting standards of quality and safety for the collection, testing, processing, storage and distribution of human blood and blood components and amending Directive 2001/83/EC. L33. Off J Eur Union 2003;30. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fordham J, Dhingra N, editors. Towards 100% voluntary blood donation: a global framework for action. Geneva: WHO Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lacetera N, Macis M. Do all material incentives for pro‐social activities backfire? The response to cash and non‐cash incentives for blood donations. J Econ Psychol 2010;31:738‐48. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Niza C, Tung B, Marteau TM. Incentivizing blood donation: systematic review and meta‐analysis to test Titmuss' hypotheses. Health Psychol 2013;32:941‐9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weidmann C, Schneider S, Weck E, et al. Monetary compensation and blood donor return: results of a donor survey in southwest Germany. Transfus Med Hemother 2014;41:257‐62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chell K, Davison TE, Masser B, et al. A systematic review of incentives in blood donation. Transfusion 2018;58:242‐54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Piersma TW, Bekkers R, Klinkenberg EF, et al. Individual, contextual and network characteristics of blood donors and non‐donors: a systematic review of recent literature. Blood Transfus 2017;15:382‐97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Kort W, Wagenmans E, van Dongen A, et al. Blood product collection and supply: a matter of money? Vox Sang 2010;98(3 Pt 1):e201‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Healy K. Embedded altruism: blood collection regimes and the European Union's donor population. Am J Sociol 2000;105:1633‐57. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Healy K. Altruism as an organisational problem: the case of organ procurement. Am Sociol Rev 2004;69:387‐404. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bednall TC, Bove LL. Donating blood: a meta‐analytic review of self‐reported motivators and deterrents. Transfus Med Rev 2011;25:317‐34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boulware LE, Ratner LE, Ness PM, et al. The contribution of sociodemographic, medical, and attitudinal factors to blood donation among the general public. Transfusion 2002;42:669‐78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gillespie TW, Hillyer CD. Blood donors and factors impacting the blood donation decision. Transfus Med Rev 2002;16:115‐30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Glynn SA, Kleinman SH, Schreiber GB, et al. Motivations to donate blood: demographic comparisons. Transfusion 2002;42:216‐25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Veldhuizen I, van Dongen A. Motivational differences between whole blood and plasma donors already exist before their first donation experience. Transfusion 2013;53:1678‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bekkers RHFP, Wiepking P. A literature review of empirical studies of philanthropy: eight mechanisms that drive charitable giving. Nonprofit Voluntary Sect Q 2011;40:924‐73. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bekkers RHFP, Wiepking P. Testing mechanisms for philanthropic behavior. Int J Nonprofit Voluntary Sect Mark 2011;16:291‐7. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wiepking P, Bekkers RHFP. Who gives? A literature review of predictors of charitable giving. Part two: gender, marital status, income, and wealth. Volunt Sect Rev 2012;3:217‐45. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Merz EM, van den Hurk K, de Kort WLAM. Organ donation registration and decision‐making among current blood donors in The Netherlands. Prog Transplant 2017;27:266‐72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Merz EM, Zijlstra BJ, de Kort WL. Perceived blood transfusion safety: a cross‐European comparison. Vox Sang 2015;110:258‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. European Commission . Eurobarometer 82.2 (2014). TNS opinion [producer]. Cologne, Germany: GESIS Data Archive; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 27. United Nations Development Programme . The human development report 2009. Overcoming barriers: human mobility and development. New York: United Nations Development Programme; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sundermann LM, de Kort WL, Boenigk S. The 'Donor of the future project' ‐ first results and further research domains. Vox Sang 2017;112:191‐200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Atsma F, Veldhuizen I, de Vegt F, et al. Cardiovascular and demographic characteristics in whole blood and plasma donors: results from the Donor InSight study. Transfusion 2011;51:412‐20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sümnig A, Feig M, Greinacher A, et al. The role of social media for blood donor motivation and recruitment. Transfusion 2018;58:2257‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lemmens KP, Abraham C, Hoekstra T, et al. Why don't young people volunteer to give blood? An investigation of the correlates of donation intentions among young nondonors. Transfusion 2005;45:945‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Slonim R, Wang C, Garbarino E. The market for blood. J Econ Perspect 2014;28:177‐96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Merz EM, Ferguson E, van Dongen A. Psychosocial characteristics of blood donors influence their voluntary nonmedical lapse. Transfusion 2018;58:2596‐603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lacetera N, Macis M, Slonim R. Public health. Economic rewards to motivate blood donations. Science 2013;340:927‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Abolghasemi H, Hosseini‐Divkalayi NS, Seighali F. Blood donor incentives: a step forward or backward. Asian J Transfus Sci 2010;4:9‐13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bagot KL, Murray AL, Masser BM. How can we improve retention of the first‐time donor? A systematic review of the current evidence. Transfus Med Rev 2016;30:81‐91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Follea G, Aranko K, European Blood A. The revision of the European blood directives: a major challenge for transfusion medicine. Transfus Clin Biol 2015;22:141‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ferguson E, Dorner L, France CR, et al. Blood donor behaviour, motivations and the need for a systematic cross‐cultural perspective: the example of moral outrage and health and non‐health based philanthropy across seven countries. ISBT Sci Ser 2018;13:375‐83. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ferguson E. Blood donation and dictator game allocations varying the source of the allocation. European Conference on Donor Health and Management. Copenhagen; 2018.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Percentage of participants who indicated agreement with the statements regarding transfusion concerns.

Table S2. Perceived Transfusion Safety as Predicted by Concerns of Non‐Donors and Donors.

Table S3. Percentage of participants who find incentives appropriate, and whether this predicted donation willingness, using logistic regressions