The leaf interior is a moist realm, in which wet cells exchange gases with large airspaces, across a surface area hundreds or thousands of times greater than the stomatal pores that connect it to the external environment. But how moist is it? Given this imbalance between evaporating surfaces and outlets for water vapor, most botanists have long assumed that leaf airspaces are essentially saturated with humidity. This saturated environment is what you would experience sitting in a wet sauna or walking on a rainy day under an umbrella. Most scientists believe this is the experience of cells in the leaf interior.

As it happens, the humidity inside leaves is not an esoteric issue. In fact, it has important implications for understanding how our biosphere functions. The airspace humidity fundamentally affects the way we study and model stomatal function and photosynthesis, which together strongly determine the productivity of all terrestrial ecosystems. Although a few researchers have concluded the airspaces were unsaturated (e.g., Jarvis and Slatyer, 1970; Canny and Huang, 2006), others reported evidence supporting saturation (Farquhar and Raschke, 1978; Sharkey et al., 1982), and the issue has, tacitly, been considered resolved in the broader plant physiology community.

Specialists who focus on this question were thus surprised by a recent report (Cernusak et al., 2018) that concluded the leaf airspaces in Pinus edulis and Juniperus monosperma are unsaturated, with relative humidity (RH) as low as 77% and 87%, respectively. That conclusion was based on a complex analysis of indirect evidence, including water and carbon fluxes into and out of the leaf and their isotopic composition. In brief, the authors compared two estimates of the stable oxygen isotope signature of CO2 at the chloroplast surface, made with different instruments, and used a sophisticated model to infer the RH of the leaf airspaces. Although no quantitative uncertainty analysis was reported, the authors considered possible issues with the calculation and concluded none would alter the inference that RH was much lower than 100%.

Given the indirectness and complexity of the estimation of humidity, we cannot yet embrace as fact the conclusion that the leaf airspaces are unsaturated. Indeed, as we argue below, it is essential that the result be independently confirmed in other laboratories and other taxa. We also believe, however, that the finding must be taken seriously to consider its potential wide‐ranging implications. The long‐held assumption that the leaf airspaces are saturated allows many calculations that are critical in plant, environmental, and geophysical sciences. First, if the airspaces are saturated, the vapor pressure within the leaf can be estimated from leaf temperature, and knowing the airspace vapor pressure in turn makes it possible to calculate leaf stomatal conductance and the [CO2] in the leaf airspaces from gas exchange measurements (Caemmerer and Farquhar, 1981). Such calculations are the foundation of modern understanding of leaf carbon and water exchange. If airspaces were unsaturated, current methods would greatly underestimate the true stomatal conductance (e.g., if the leaf airspaces were at RH = 80% and the ambient air were at 20%, conductance would be underestimated by about one‐quarter). Although unsaturation would not affect direct measurements of fluxes by gas exchange, such as photosynthesis and transpiration rates, it would affect inferences based on any quantity whose calculation depends on stomatal conductance, including leaf intercellular [CO2], photosynthetic capacity (which is estimated by fitting models to the relationship between net photosynthesis rate and intercellular [CO2]), and photosynthesis rate. Many published gas exchange results and predictions would have to be reconsidered and, in some cases, discarded.

Equally important are the implications of unsaturation for our understanding of leaf water relations and water transport. If airspaces are unsaturated, this fact would challenge the current consensus on leaf water transport and require new understanding of these processes.

UNSATURATED AIRSPACES IMPLY EXTREMELY NEGATIVE WATER POTENTIALS

Unsaturation of leaf airspaces would suggest that the water potential of water in leaf cell walls, i.e., the extracellular or non‐xylem “apoplastic” water, is far more negative than currently thought. At equilibrium, the water potential (ψ) of an aqueous solution is a function of the relative humidity over the solution:

| (1) |

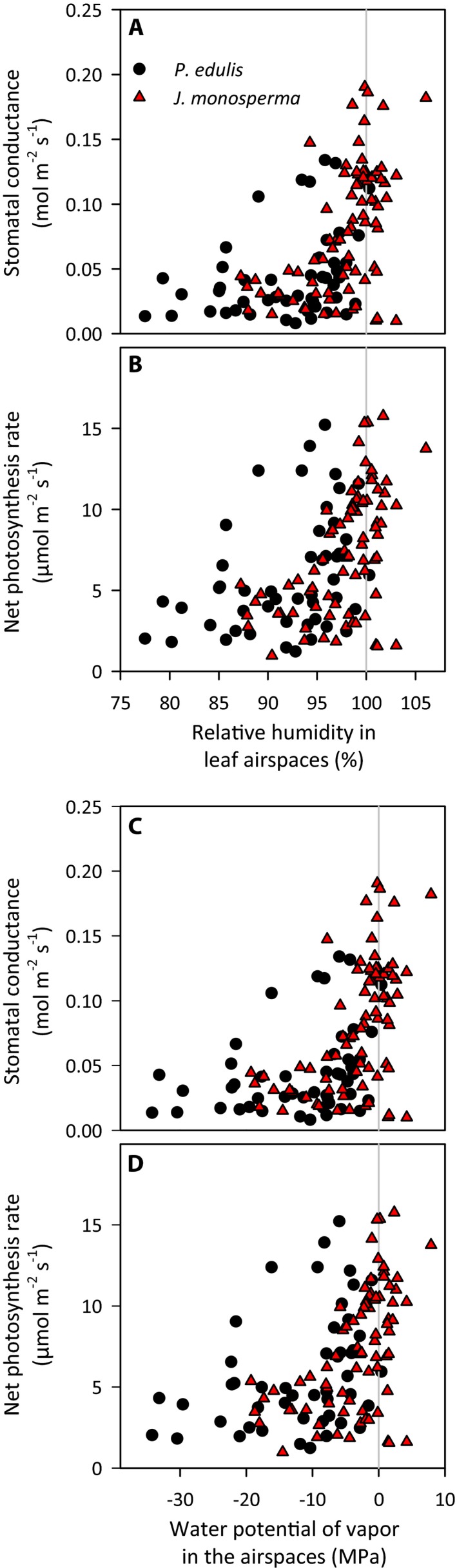

where v w is the molar volume of water (1.8·10‐5 mol m−3), R is the gas constant (8.314·10‐6 MPa m3 mol−1 K−1) and T is temperature in kelvins. The effect of RH on ψ is strong: a 1% decline in RH reduces ψ by ~1.4 MPa. At RH = 88% (the 25th percentile of values reported for P. edulis; Fig. 1), equilibrium ψ of apoplastic water ≈ −18 MPa, an enormously negative number. At the lowest reported value of RH, 77%, ψ ≈ −35 MPa.

Figure 1.

Measured leaf gas exchange variables (A, B: stomatal conductance to water vapor; C, D: net photosynthesis rate) in relation to inferred relative humidity of the leaf airspaces (A, C) and water potential of airspace vapor (B, D), for Pinus edulis (black circles) and Juniperus monosperma (red triangles), from Cernusak et al. (2018).

Apoplastic water would not be exactly in water potential equilibrium with vapor in the airspaces during transpiration, because diffusion of vapor away from an evaporating surface creates gradients in vapor concentration and thus ψ. However, our calculations indicate that these gradients are small (e.g., <0.008 MPa μm−1 for P. edulis and <0.011 MPa μm−1 for J. monosperma) (calculations described in Appendix S1 and demonstrated in Appendix S2). It is also possible that evaporation occurs only from sites close to the vasculature, so that vapor has to diffuse through a long and tortuous path to reach the stomatal pores, which could generate a large gradient in vapor concentration and hence very negative water potentials near the stomatal pore. However, the technique used by Cernusak et al. (2018) produces an estimate of the vapor pressure of air in equilibrium with the evaporating site, not the vapor pressure near the stomatal pore per se. The conclusion thus remains that apoplastic water potential would therefore be close to the very negative values mentioned earlier (−18 to −35 MPa).

UNSATURATION WOULD REQUIRE NEW TRANSPORT BIOLOGY

Such extraordinarily low water potentials could not occur within xylem conduits or living cells of functioning leaves. In P. edulis, stomata close and photosynthesis ceases when soil water potential drops below around −3 MPa (Adams et al., 2013). Xylem water transport is fully impeded by gas bubbles, or emboli, that form below −3 MPa in leaves (Woodruff et al., 2015) and −6 to −7 MPa in stems and roots (Linton et al., 1998). Similar thresholds have been found in other species (Bartlett et al., 2016). Yet Cernusak et al. (2018) reported unsaturation in leaves with open stomata and active photosynthesis (Fig. 1).

To reconcile these disparate observations, one must hypothesize that bulk leaf and xylem cell water potentials can somehow remain high while water potential is extremely negative in the apoplast. There is no conceptual barrier to this hypothesis: cell walls contain only a small fraction of leaf water, whereas bulk leaf water potential is determined by the water potentials of the largest water compartments, mainly living cells and xylem conduits. What is less clear is how such a large difference in water potential could be sustained between those compartments and the non‐xylem apoplast. That would require major changes in our understanding of how water and CO2 move within leaves:

First, membranes would have to be far less permeable to water than currently thought. For example, to sustain a water potential of −2 MPa inside mesophyll cells, with ψ in the adjacent apoplastic water as predicted by Eq. 1 for the data of Cernusak et al. (2018), the water permeability of mesophyll cell membranes would need to be hundreds to thousands of times smaller than previously reported (Appendix S3).

Second, membranes must have previously unknown selectivity for CO2 transport relative to water transport. Cernusak et al. (2018) reported very high conductances for CO2 transport from the intercellular airspaces to the chloroplast surface, which implies high membrane conductivity to CO2. Given the very low membrane water permeability implied by airspace unsaturation, membranes must contain transporters, yet undiscovered, that allow CO2 to pass easily while blocking water transport.

Third, water flow from veins to distant mesophyll cells must be dominated by intracellular (“symplastic”) pathways. To sustain high water potential within living cells far from the xylem, a high‐conductivity pathway must connect those cells to the xylem, but that pathway cannot involve the apoplast or airspaces due to their extremely low ψ implied by unsaturation. Plasmodesmata are the only known candidate for such a pathway, but evidence from cell pressure‐probe experiments (Fricke, 2000) and isotopic studies (Barbour and Farquhar, 2004) suggests that plasmodesmata are not conductive enough to contribute substantially to water movement between cells.

WHAT NEXT?

If verified, unsaturation of the leaf airspaces would alter our understanding of many features of plant biology, from the biophysics of CO2 and water transport to carbon‐water relations and the role of stomata. It would also require acute reassessment of decades of gas exchange measurements. It is therefore crucial to experimentally verify this phenomenon and its implications. We suggest the following steps: (1) The original experiments should be repeated, preferably by independent lab groups and on a range of taxa. (2) Replication studies should include measurements of leaf water potential to verify that unsaturation co‐occurs with high bulk leaf water potentials. (3) Other approaches to estimate intercellular humidity should also be employed. For example, the method of Sharkey et al. (1982) to estimate airspace [CO2] in amphistomatous leaves could be adapted to estimate intercellular vapor pressure, and new nano‐sensing technology may enable direct measurement of vapor pressure within leaves (e.g., Kuang et al., 2007). Progress on these fronts would not only resolve the question of saturation, but could also generate new insights about the mechanisms of leaf CO2 and water transport and the interpretation of stable isotope discrimination and lead to improved methods for studying photosynthesis and leaf carbon–water relations.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Gradients in water potential of water vapor in leaf airspaces.

Appendix S2. Spreadsheet illustrating calculations.

Appendix S3. Mesophyll osmotic water permeability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Lucas Cernusak for providing the original data and our lab groups, colleagues, three anonymous referees, and Jim Ehleringer for helpful comments. T.N.B. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation (award no. 1557906), the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture (Hatch project 1016439), and the Almond Board of California (18.HORT37), and LS received support from the National Science Foundation (award no. 1457279).

Buckley, T. N. and Sack Lawren. 2019. The humidity inside leaves and why you should care: implications of unsaturation of leaf intercellular airspaces. American Journal of Botany 106(5): 618–621.

LITERATURE CITED

- Adams, H. D. , Germino M. J., Breshears D. D., Barron‐Gafford G. A., Guardiola‐Claramonte M., Zou C. B., and Huxman T. E.. 2013. Nonstructural leaf carbohydrate dynamics of Pinus edulis during drought‐induced tree mortality reveal role for carbon metabolism in mortality mechanism. New Phytologist 197: 1142–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour, M. M. , and Farquhar G. D.. 2004. Do pathways of water movement and leaf anatomical dimensions allow development of gradients in H2 18O between veins and the sites of evaporation within leaves? Plant, Cell & Environment 27: 107–121. [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett, M. K. , Klein T., Jansen S., Choat B., and Sack L.. 2016. The correlations and sequence of plant stomatal, hydraulic, and wilting responses to drought. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 113: 13098–13103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caemmerer, S. , and Farquhar G. D.. 1981. Some relationships between the biochemistry of photosynthesis and the gas exchange of leaves. Planta 153: 376–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canny, M. J. , and Huang C. X.. 2006. Leaf water content and palisade cell size. New Phytologist 170: 75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernusak, L. A. , Ubierna N., Jenkins M. W., Garrity S. R., Rahn T., Powers H. H., Hanson D. T., et al. 2018. Unsaturation of vapour pressure inside leaves of two conifer species. Scientific Reports 8: 7667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, G. D. , and Raschke K.. 1978. On the resistance to transpiration of the sites of evaporation within the leaf. Plant Physiology 61: 1000–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke, W. 2000. Water movement between epidermal cells of barley leaves – a symplastic connection? Plant, Cell & Environment 23: 991–997. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis, P. G. , and Slatyer R. O.. 1970. The role of the mesophyll cell wall in leaf transpiration. Planta 90: 303–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang, Q. , Lao C., Wang Z. L., Xie Z., and Zheng L.. 2007. High‐sensitivity humidity sensor based on a single SnO2 nanowire. Journal of the American Chemical Society 129: 6070–6071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linton, M. , Sperry J., and Williams D.. 1998. Limits to water transport in Juniperus osteosperma and Pinus edulis: implications for drought tolerance and regulation of transpiration. Functional Ecology 12: 906–911. [Google Scholar]

- Sharkey, T. D. , Imai K., Farquhar G. D., and Cowan I. R.. 1982. A direct confirmation of the standard method of estimating intercellular partial pressure of CO2 . Plant Physiology 69: 657–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodruff, D. R. , Meinzer F. C., Marias D. E., Sevanto S., Jenkins M. W., and McDowell N. G.. 2015. Linking nonstructural carbohydrate dynamics to gas exchange and leaf hydraulic behavior in Pinus edulis and Juniperus monosperma . New Phytologist 206: 411–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Gradients in water potential of water vapor in leaf airspaces.

Appendix S2. Spreadsheet illustrating calculations.

Appendix S3. Mesophyll osmotic water permeability.