Abstract

The refugee and homeless population has been increasing worldwide in recent years. Staff in social work provide practical help to these populations, but often struggle with high job demands. This scoping review aims to systematically map the job demands, resources, mental health problems, coping strategies and needs of staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals. Relevant studies were identified by searching seven electronic databases from their inception until the end of May 2018, as well as Google Scholar and reference lists of included articles. The methodological quality of the included studies was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. A thematic analysis was conducted. Twenty‐five studies were included in the review. Fourteen studies followed a quantitative approach, six a qualitative approach and five a mixed‐method approach. Most studies were conducted in the homeless sector (56%), in North America (52%) and published after the year 2009 (68%). Common job demands included the bureaucratic system, high caseloads, clients' suffering and little experience of success. Maintaining professional boundaries counted both as a job demand and a coping strategy. Deriving meaning from work and support from the team were identified as important job resources. The prevalence of mental health problems among staff was high, but difficult to compare due to the use of different instruments in studies. Staff expressed a need for ongoing training, external counselling and supervision. Further studies should examine the effectiveness of workplace health interventions.

Keywords: homelessness, job demands and resources, mental health, refugees, scoping review, social work

What is known about this topic

The numbers of refugees and homeless individuals have recently been increasing worldwide, leading to a need for qualified staff in social work providing practical help to these highly vulnerable client groups.

Staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals may face particular job demands, as their clients often suffer from serious traumatic experiences.

What this paper adds

Encountering client's suffering and the inability to change the situation of clients was specifically demanding for staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals.

Staff had good job satisfaction regardless of mental health problems.

The effectiveness of workplace health interventions aimed at reducing job demands and strengthening job and personal resources should be further investigated.

1. INTRODUCTION

Flight and homelessness are increasing social problems today. The number of refugees worldwide is at the highest level ever recorded. By the end of 2017, 25.4 million refugees were counted (UNHCR, 2018). Homelessness has considerably increased during recent years in almost all countries of the European Union (FEANTSA & Fondation Abbé Pierre, 2018). In the course of these developments, the need for qualified staff in social services in countries such as Germany has increased considerably, especially in the area of refugee aid (Filsinger, 2017). Staff in social services such as reception centres, emergency shelters, counselling centres and outreach and drop‐in services provide a variety of social work activities to refugees or homeless individuals. Amongst others, they support them in legal matters, in preparing applications, in finding accommodation, accompany them to local authorities and refer them to further assistance (Filsinger, 2017; Kosny & Eakin, 2008). The structure of staff, their professional education and their specific work tasks differ between services and countries. In this review they are further described under the collective term ‘staff in social work’ and it is aimed to examine their working conditions as a whole.

This review follows two different theoretical models, namely the Job Demands‐Resources model (J‐DR model; Bakker & Demerouti, 2007) and the Transactional Model of Stress and Coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). The J‐DR model assumes that every occupation has its own specific job resources and demands. These can refer to areas such as the organisation of work, the job content, the social relations or the physical work environment. The model further assumes that available job resources have a motivational potential and can lead to engagement, while job demands are associated with employees' strain and the development of health problems (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). The Transactional Model of Stress and Coping describes how people try to manage and cope with demands they perceive as stressful. The model assumes that coping has two functions: one refers to regulating emotional distress caused by a stressful situation (emotion‐focused coping) and one refers to solving the problem (problem‐focused coping; Folkman, Lazarus, Dunkel‐Schetter, DeLongis, & Gruen, 1986; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

Studies have examined the job resources and demands of social workers in various fields of work. Some general resources and demands for social work can be derived from these studies. On the one hand, social workers find reward in helping others, are committed to their workplace and perceive their social support from colleagues and supervisors as high (Drüge & Schleider, 2016; Stalker, Mandell, Frensch, Harvey, & Wright, 2007). On the other hand, they struggle under permanent changes in social policy and legislation, restricted financial resources and limited control and decision latitudes (Lloyd, King, & Chenoweth, 2002). In a study sample of social workers from the Nordic countries, 42% experienced heavy workloads and 45% major role conflicts (Blomberg, Kallio, Kroll, & Saarinen, 2015). German social workers perceived their quantitative demands (mean [M] = 62 vs. 55) and emotional demands at work (M = 69 vs. 52, both p < 0.001) higher than other professionals did (Drüge & Schleider, 2016). In accordance with the J‐DR model, job resources such as finding reward, commitment and a sense of community were associated with job satisfaction, while high workload, role ambiguity and bureaucratic working conditions were associated with burnout (Beckmann, Maar, Otto, Schaarschuch, & Schrödter, 2009; Söderfeldt, Söderfeldt, & Warg, 1995; Yürür & Sarikaya, 2012). Accordingly, studies found that social workers experienced above‐average levels of burnout (Borritz et al., 2006; Lloyd et al., 2002). The use of coping strategies was found to buffer the effects of work stress on burnout variables and job satisfaction in social work samples (Stalker et al., 2007). Anderson (2000) found that if child protection workers used active coping strategies such as problem solving more, it lessened their feelings of depersonalisation and increased their sense of personal accomplishment.

Refugees and homeless individuals represent highly vulnerable client groups who often suffer from traumatic experiences. Refugee aid workers and staff in shelters for the homeless reported that about 40%–60% of their clients were traumatised (Pell, 2013; Schutt & Fennell, 1992). These numbers indicate that staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals are likely to be exposed to the serious traumatic histories of their clients. It is known that professionals working with traumatised clients are susceptible to secondary traumatic stress, also described as vicarious traumatisation or compassion fatigue (Figley, 1995). These concepts refer to the negative impacts of indirect trauma exposure, leading to symptoms of intrusion, avoidance and arousal (Figley, 1995; Molnar et al., 2017).

So far, literature reviews have focused on stress, burnout, job satisfaction or resilience in child welfare workers (McFadden, Campbell, & Taylor, 2015; Stalker et al., 2007), mental health social workers (Coyle, Edwards, Hannigan, Fothergill, & Burnard, 2005) or in unspecified fields of social work (Lloyd et al., 2002; Söderfeldt et al., 1995). Although it can be assumed that staff in social work serving refugees and homeless individuals may face particular demands in their work with clients, little is known about their specific working conditions and potential strain. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study which aims to systematically map the existing literature about the job demands, personal and job resources, mental health, coping strategies and needs of staff in social work serving highly vulnerable client groups (refugees and homeless individuals). By this, the review aims to identify existing gaps in the literature and to create a basis for the development of specific health promotion measures for employees in this field of work.

2. METHODS

A scoping review was conducted because it allows to answer wider research questions and to include studies with a variety of study designs. This review followed the framework introduced by Arksey and O'Malley (2005).

2.1. Stage 1: Identifying the research questions

This scoping review addressed the following research questions. All of them refer to staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals.

What job demands and job and personal resources of this staff are described in the literature?

How prevalent are mental health problems among this staff?

Which demands and resources are associated with the mental health of this staff?

What coping strategies are adopted by this staff in handling their perceived job demands?

What kind of interventions and needs for improving the work and health situation of this staff are known from the literature?

2.2. Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

Relevant studies were identified through an extensive search in the following seven electronic databases: PubMed, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PSYNDEX, CINAHL, Web of Science and SOWIPORT. All databases were searched from their inception until the end of May 2018, except for SOWIPORT which was searched only until December 2017 because the database was closed after that. English search terms were combined which referred to the population, exposure (field of work and client group) and outcome. The search strategy was initially developed for the PubMed database and then converted to all other databases (see Table S1). To identify any further relevant studies, Google Scholar was searched, first, combining the terms (“refugee” or “asylum seeker” or “homeless”) and (“worker” or “professional” or “staff”) and (“demands” or “resources” or “mental health”) and, second, combining German translations of these terms. The first 100 hits, sorted according to their relevance, were screened in Google Scholar. Four potentially relevant studies published in English and two published in German were identified. Finally, reference lists of all articles included after the full text screening were searched by hand.

2.3. Stage 3: Study selection

The study selection was based on predetermined inclusion and exclusion criteria. The review included studies conducted on staff engaged in social work activities who offered practical help and support to refugees or homeless individuals and had direct contact with these clients. If studies involved besides staff with social work activities, also other occupational groups of an organisation (e.g. administrative staff), these were also considered for this review. Studies which solely focused on voluntary workers or clinical social workers/therapists were excluded, as well as studies which were conducted in war and crisis areas. Studies were included when they reported results on the main outcomes of interest such as job demands, jobs and personal resources, mental health, coping and workplace health interventions. Observational studies, qualitative and mixed methods research designs and intervention studies were included in the review. Reviews, letters, editorials, conference papers, commentaries, reflections, policy statements and books were not considered. Full texts had to be published and made available in languages the research team was capable of (English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, Portuguese and Turkish). The title and abstract screening was conducted by one reviewer (TW). Titles/abstracts for which no decision could be made by the reviewer (N = 23) were discussed with the research team. Full texts of studies were screened independently by two reviewers (TW and JP). Whenever different decisions about inclusion or exclusion were made, these were discussed in the research team until consent was reached. The inter‐rater reliability was measured by Cohen's kappa statistics.

2.4. Stage 4: Charting the data

Data from the included studies were extracted by one reviewer (TW) and verified by a second reviewer (JM). At first, general information on authors, year of publication, country, publication type, aims and objectives, study design, population, exposure, outcomes and data collection instruments were extracted from studies into a standardised Excel® spreadsheet. Then, key findings of studies were also charted using a standardised Excel® spreadsheet according to the different research questions. The following major categories were deductively developed: demands and resources (with subcategories: organisation of work, job content, social relations, work environment, personal factors), mental health, coping strategies and interventions and needs. Key findings from qualitative components of studies were coded to these categories using auxiliary qualitative software (MAXQDA version 11). For one study, additional information on findings were requested from the author (Sundqvist, Hansson, Ghazinour, Ogren, & Padyab, 2015).

2.5. Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting the results

The charted characteristics of the studies were summarised descriptively, including the calculation of frequencies, and presented in tables. A thematic analysis was conducted using qualitative data analytical techniques, as suggested by Levac, Colquhoun, and O'Brien (2010) to organise and summarise the findings of the studies. Findings related to the study questions were reported narratively and in a table according to the major categories and subcategories.

2.6. Quality assessment

The application of a quality assessment in scoping reviews is still under discussion (Arksey & O'Malley, 2005; Levac et al., 2010). Daudt, Mossel, and Scott (2013) recently recommended adding this stage into the framework. In this scoping review, we sought to make statements on the methodological depth of the existing literature. Therefore, two reviewers (TW and JM) independently assessed the methodological quality of the included studies using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT; Pluye et al., 2011). Differing results were discussed until consent was reached. The inter‐rater reliability was measured by Cohen's kappa statistics.

3. RESULTS

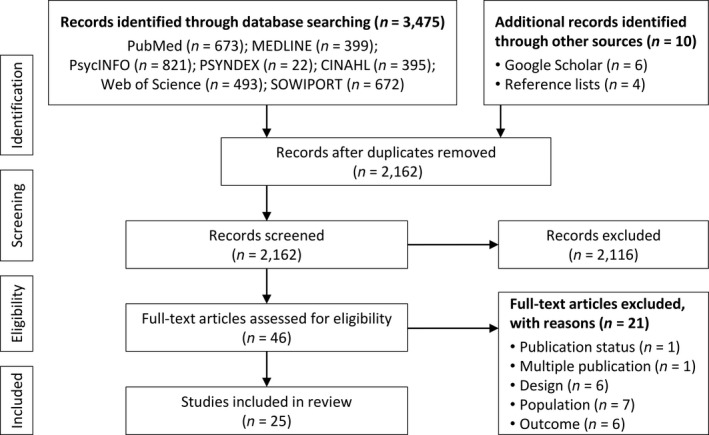

Overall, 2,162 records were screened in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 2,116 records were excluded and 46 full texts were assessed for eligibility. Finally, 25 studies were included in the scoping review (Figure 1). A good inter‐rater agreement for the full text screening was reached between the two reviewers (Cohen's Kappa = 0.73).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow chart of the study selection process

3.1. Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 25 studies are described in Table 1. Of the 14 studies in the homeless sector, five examined agency staff, three were conducted in community programs, two in homeless shelters and four included several settings. Eleven studies examined professionals working with refugees. Seven of these studies were conducted at agencies or service centres, one at non‐governmental organisations, one at reception centres, one examined participants of a training course and one included several settings. Three studies involved the same sample of social workers who served unaccompanied refugee children due for forced repatriation (Sundqvist, Ghazinour, & Padyab, 2017; Sundqvist et al., 2015; Sundqvist, Padyab, Hurtig, & Ghazinour, 2017). Some studies did not only include staff in social work, but also other occupational groups, such as administrative staff, nurses, directors or paraprofessionals. In all but one study, the majority of participants were female (54%–84%). Five studies did not report gender distributions. Only one study had a longitudinal design and was intervention‐based (Chapleau, Seroczynski, Meyers, Lamb, & Haynes, 2011). For detailed study characteristics, please see Table S2.

Table 1.

Overview of characteristics of included studies (N = 25)

| Characteristics | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Study approach | ||

| Quantitative | 14 | 56 |

| Qualitative | 6 | 24 |

| Mixed methods | 5 | 20 |

| Continent of study | ||

| North America | 13 | 52 |

| Europe | 9 | 36 |

| Asia | 1 | 4 |

| Australia | 1 | 4 |

| Australia and Europe | 1 | 4 |

| Year of publication | ||

| 2010–May 2018 | 17 | 68 |

| 2000–2009 | 4 | 16 |

| 1990–1999 | 3 | 12 |

| <1990 | 1 | 4 |

| Publication type | ||

| Journal article, peer reviewed | 20 | 80 |

| Thesis or dissertation | 3 | 12 |

| Journal article, non‐peer reviewed | 1 | 4 |

| Study report | 1 | 4 |

| Client group | ||

| Homeless individuals | 14 | 56 |

| Refugees | 11 | 44 |

3.2. Demands and resources reported by participants in the included studies

In qualitative interviews and surveys, study participants reported job demands which they perceived as negative or lead to feelings of frustration and stress, as well as a variety of job and personal resources which helped them to stay passionate and positive about their jobs. We assigned these demands and resources to the categories of organisation of work, job content, social relations and personal factors; none were identified in the context of the work environment.

3.2.1. Organisation of work

Five studies found that working in a bureaucratic environment was a job demand for staff in social work in the refugee and homeless sector. In particular, staff perceived the welfare system as unfair and limiting their possibilities to help their clients, for example due to poor financial resources. They also reported difficulties in accessing mainstream services and in dealing with other agencies (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Kidd, Miner, Walker, & Davidson, 2007; Kosny & Eakin, 2008; Robinson, 2014). Francis (2000) explicitly noted contradictions between the bureaucratic system and client needs, which led to role conflicts faced by case managers for the homeless. Three studies further mentioned low pay as causing financial stress to staff in the refugee and homeless sector (Hagen & Hutchison, 1988; Kidd et al., 2007; Robinson, 2014).

Some further job demands were only named in studies concerning the refugee or homeless sector. Two studies of caseworkers working with homeless individuals identified excessive paperwork and documentation as a job demand (Chapleau et al., 2011; Sutton‐Brock, 2013). Being employed only on short‐term contracts and dealing with rapid changes in policies were described as challenges for frontline refugee workers (Robinson, 2014).

Only one study identified a job resource in the context of the organisation of work. Some caseworkers in a homeless shelter perceived their unconventional working hours as a benefit, allowing for greater flexibility (Sutton‐Brock, 2013).

3.2.2. Job content

With respect to staffs' job content, a high caseload was named in five studies as a relevant job demand. In a cross‐sectional survey, one fourth of caseworkers in a homeless shelter regarded their caseload as too high (Sutton‐Brock, 2013). In qualitative interviews, staff reported heavy and increasing workloads and caseloads. As a consequence, they worked overtime, felt a lack of control over clients and were concerned about a diminished quality of service (Chapleau et al., 2011; Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Robinson, 2014; Sutton‐Brock, 2013). Another demand identified was a low decision latitude and low control. In a German survey, 60% of refugee aid workers reported having low control at work, mainly due to legal regulations (Grimm et al., 2017). Further studies found that caseworkers for the homeless were concerned about having little or no impact on management's decisions (Chapleau et al., 2011; Sutton‐Brock, 2013). Four studies in the refugee sector and three studies in the homeless sector identified encountering clients' suffering and regularly hearing clients' stories and traumatic experiences as a major demand (Ferris et al., 2016; Grimm et al., 2017; Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Kidd et al., 2007; Kosny & Eakin, 2008; Lusk & Terrazas, 2015; Robinson, 2014). The inability to change the situation of their clients or the little success staff experience in their work were also frequently reported (Chapleau et al., 2011; Kidd et al., 2007; Lusk & Terrazas, 2015; Robinson, 2014; Sutton‐Brock, 2013). Furthermore, ethical questions played a role: in one study, staff members of a refugee centre experienced distress caused by moral dilemmas in situations in which they became aware of unlawful behaviour of their clients (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011). Similarly, youth workers in ‘zero‐tolerance’ agencies for the homeless perceived themselves to be in an ethically questionable position when they had to discharge youth onto the streets for minor infractions (Kidd et al., 2007).

Other demands concerning the job content were more specific to the refugee or homeless sector. Lakeman (2011) conducted in‐depth interviews with homeless sector workers having served people who had subsequently died. Particularly stressful to these workers were sudden and unexpected deaths, deaths caused by overdose, suicide or homicide and being witness to the death of a person or the dead body. Two studies from the refugee sector identified language barriers in the communication with clients (Grimm et al., 2017; Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011). About half of the refugee aid workers participating in a German cross‐sectional survey reported communication problems as a distress factor (Grimm et al., 2017).

On the other hand, it was noted in a variety of studies that working in the refugee and homeless sector strongly supported staffs’ beliefs, values and interests (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Kidd et al., 2007; Robinson, 2014). Furthermore, they could derive strong meaning from their work (Ferris et al., 2016; Kidd et al., 2007; Robinson, 2014). In a cross‐sectional survey of service providers for the homeless population, 65% believed that their work positively influenced people's lives, and 83% felt at least moderately successful in their work with clients (Hagen & Hutchison, 1988). Similarly, among caregivers working with refugees, all participants reported being proud of their work and 90% gained satisfaction from helping people (Lusk & Terrazas, 2015). Two studies found that seeing change in refugees and homeless individuals and receiving their gratitude was most rewarding to staff in social work (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Kidd et al., 2007).

3.2.3. Social relations

Demands and resources in the context of social relations were connected to clients as well as to colleagues and supervisors. One of the main job demands for staff in social work was to maintain professional boundaries with their refugee and homeless clients, as they often felt personally responsible for them (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Kidd et al., 2007; Kosny & Eakin, 2008; Mowbray, Thrasher, Cohen, & Bybee, 1996; Robinson, 2014). One study reported that staff were taking risks to help their clients. This included seeing clients in unfamiliar places or interacting with drug dealers (Kosny & Eakin, 2008). Some qualitative studies also found that staff struggled with unrealistic demands from clients and encountered violent and aggressive behaviours by clients (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Kidd et al., 2007; Kosny & Eakin, 2008). Among a sample of refugee aid workers, 27% perceived aggressive behaviour by clients as a distress factor (Grimm et al., 2017).

Other job demands were only reported in studies concerning the refugee or homeless sector. Two studies from the homeless sector mentioned problems with supervisors and colleagues. Chapleau et al. (2011) found that case managers were frustrated about the little support and recognition they received from direct supervisors and management. Kidd et al. (2007) noted that high turnover of staff in agencies for homeless youth disrupted collaborative work within the team. In three studies, refugee workers struggled with negative reactions from family, friends or the general public towards their work. Specifically, they reported a lack of understanding from others in relation to their work and feelings of isolation (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Lusk & Terrazas, 2015). Moreover, they described discrimination and racism by mainstream providers and members of the public and even physical attacks on themselves by members of the public (Robinson, 2014).

In most studies, support from the team was mentioned as an important job resource concerning social relations (Ferris et al., 2016; Kidd et al., 2007; Lusk & Terrazas, 2015; Mowbray et al., 1996). Kidd et al. (2007) noted that youth workers described the importance of a good leader in the development of a collaborative working environment. Among caregivers working with refugees, 81% reported that they felt supported by their supervisors (Lusk & Terrazas, 2015).

3.2.4. Personal factors

Personal resources were only identified in a few studies. Two studies from the homeless sector reported a sense of humour as a personal resource which helped staff to relieve stress and frustration (Kidd et al., 2007; Mowbray et al., 1996). Kidd et al. (2007) further mentioned being able to connect to homeless youth as a personal resource. Two other studies found specific personal resources which helped staff in their work with refugees. These included cultural resilience (e.g. because of an extended family system Lusk & Terrazas, 2015), having the same cultural background as clients, personal life experiences (e.g. having lived overseas) as well as the ability to be caring, patient and empathic (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011).

3.3. Demands and resources examined for their association with mental health

Using quantitative analysis techniques, 11 studies examined factors for their association with different health‐related outcome parameters such as mental health problems, job or compassion satisfaction, and occupational commitment. Two studies found that work experience was a protective factor among professionals working with refugees, being associated with lower emotional exhaustion (Kim, 2017) and higher compassion satisfaction (Lusk & Terrazas, 2015). Hours worked per week were correlated with higher compassion satisfaction in professionals of a homeless programme (Beebe, 2016) and in refugee caregivers (Lusk & Terrazas, 2015). Further factors were only identified by single studies (Table 2). Many of the job demands and resources identified through qualitative interviews and surveys have not been examined for their association with mental health in quantitative analyses, so far. Some showed no association with mental health, such as role ambiguity (Kim, 2017) and variables related to the team (Waegemakers Schiff & Lane, 2016).

Table 2.

Factors associated with different health‐related outcome parameters in quantitative analyses of included studies

|

Type of factor Outcome (statistical measure) |

N | Author (year) |

|---|---|---|

| Associated demands | ||

| Organisation of work | ||

|

Factor: access to mental health support Outcome: traumatic stress symptoms (not specified) |

245b | Waegemakers Schiff and Lane (2016) |

|

Factor: having relief support available Outcome: traumatic stress symptoms (not specified) |

245b | Waegemakers Schiff and Lane (2016) |

| Job content | ||

|

Factor: heavy workload Outcome: EE (t = 5.58, p < 0.001); DP (t = 2.33, p < 0.05) |

179a | Kim (2017) |

|

Factor: diminished sense of achievement Outcome: DP (t = 2.26, p < 0.05); lack of PA (t = 2.37, p < 0.05) |

179a | Kim (2017) |

|

Factor: high proportion of traumatised clients (>62%) Outcome: compassion fatigue (ƞ 2 = 0.04); global stress symptoms (ƞ 2 = 0.06); somatic symptoms (ƞ 2 = 0.08); anxiety (ƞ 2 = 0.07) |

115a | Pell (2013) |

| Social relations | ||

|

Factor: support by supervisors and management Outcome: traumatic stress symptoms (not specified) |

245b | Waegemakers Schiff and Lane (2016) |

| Work environment | ||

|

Factor: poor work environment Outcome: lack of PA (t = −2.01, p < 0.05) |

179a | Kim (2017) |

|

Factor: working in a reception centre in a prefabricated building versus in a park Outcome: higher risk of burnout (not specified) |

20a | Hajji (2018) |

| Personal factors | ||

|

Factor: own traumatic history Outcome: compassion fatigue (β = 0.31, p < 0.01); global stress symptoms (β = 0.44, p < 0.001); somatic symptoms (β = 0.45, p < 0.001); anxiety (β = 0.40, p < 0.001); depression (β = 0.29, p < 0.01) |

115a | Pell (2013) |

|

Factor: negative affectivity Outcome: EE (r = 0.81, p < 0.01); DP (r = 0.89, p < 0.01); lack of PA (r = 0.82, p < 0.01); burnout (r = 0.70, p < 0.01) |

32b | Schepman and Zarate (2008) |

|

Factor: secondary traumatic stress Outcome: EE (t = 4.65, p < 0.001); DP (t = 4.39, p < 0.001); lack of PA (t = 3.19, p < 0.01) |

179a | Kim (2017) |

|

Factor: emotion oriented coping strategies Outcome: compassion fatigue (ƞ 2 = 0.30), burnout (ƞ 2 = 0.06); global stress symptoms (ƞ 2 = 0.27); somatic symptoms (ƞ 2 = 0.12); anxiety (ƞ 2 = 0.29); depression (ƞ 2 = 0.23) |

115a | Pell (2013) |

| Associated resources | ||

| Organisation of work | ||

|

Factor: hours worked per week Outcome: compassion satisfaction (r = 0.42, p = 0.01) |

44b | Beebe (2016) |

|

Factor: hours per week working with migrants Outcome: compassion satisfaction (r = 0.38, p = 0.04) |

31a | Lusk and Terrazas (2015) |

|

Factor: competence and development opportunities Outcome: PA (t = −2.95, p < 0.01) |

179a | Kim (2017) |

| Job content | ||

|

Factor: satisfaction with the work itself Outcome: job satisfaction (β = 0.56, p < 0.001) |

85b | Schutt and Fennell (1992) |

|

Factor: high proportion of traumatised clients (>62%) Outcome: compassion satisfaction (ƞ 2 = 0.06) |

115a | Pell (2013) |

| Social relations | ||

|

Factor: satisfaction with co‐workers Outcome: job satisfaction (β = 0.30, p < 0.05) |

85b | Schutt and Fennell (1992) |

| Personal factors | ||

|

Factor: empathic concern Outcome: compassion satisfaction (r = 0.36, p = 0.02) |

44b | Beebe (2016) |

|

Factor: belief that the world is fair to the self Outcome: less perceived stress (β = −0.23, p < 0.01); life satisfaction (β = 0.45, p < 0.01) |

253a | Khera, Harvey, and Callan (2014) |

|

Factor: personal commitment Outcome: lower EE (t = −3.38, p < 0.01); lower DP (t = −2.16, p < 0.05) |

179a | Kim (2017) |

|

Factor: work experience Outcome: lower EE (t = −2.08, p < 0.05) |

179a | Kim (2017) |

|

Factor: work experience Outcome: compassion satisfaction (r = 0.41, p = 0.02) |

31a | Lusk and Terrazas (2015) |

|

Factor: years living in the region Outcome: compassion satisfaction (r = 0.48, p < 0.01) |

31a | Lusk and Terrazas (2015) |

|

Factor: organisational citizenship behaviour Outcome: lower EE (r = −0.43, p < 0.05); lower burnout (r = −0.46, p < 0.01) |

32b | Schepman and Zarate (2008) |

CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio; DP, depersonalisation; EE, emotional exhaustion; PA, personal accomplishment.

Homeless sector.

Refugee sector.

Two studies tested complex statistical models among staff in the homeless sector. Miller, Birkholt, Scott, and Stage (1995) suggested that a slightly revised version of the Empathic Communication Model of Burnout provided an effective explanation of burnout among employees providing services to the homeless in a metropolitan area in the US. According to their model, emotional contagion (which involves ‘feeling with’ others) hinders effective communication and is directly related to a reduced personal accomplishment. Empathic concern (which involves ‘feeling for’ others) helps to communicate effectively and thereby enhances personal accomplishment. Personal accomplishment, in turn, influences the other two burnout variables and is positively related to occupational commitment. Ferris et al. (2016) examined two models to understand how frontline service providers in Australia deal with the suffering of their homeless clients. They found what they named the ‘Florence Nightingale effect’: perceived client suffering was linked to increased organisational identification, which, in turn, predicted less burnout and higher job satisfaction.

3.4. Mental health

Staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals reported in qualitative interviews that they had problems in mentally switching off after work and that they took clients’ issues home with them (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Kidd et al., 2007; Kosny & Eakin, 2008; Mowbray et al., 1996). It was further described that staff had feelings of frustration, demoralisation, stress and sadness as a consequence of their work (Francis, 2000; Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Lusk & Terrazas, 2015). Moreover, frontline refugee workers in Australia and the UK reported that sick leave and turnover were high (Robinson, 2014). Several staff members of a UK refugee centre reported in qualitative interviews that their work had a significant impact on their physical well‐being, resulting in tiredness and exhaustion (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011). Even though youth workers working with homeless and street‐involved youth did not consider themselves burned out, they described being exhausted and thinking of leaving the profession (Kidd et al., 2007).

Nine quantitative or mixed methods studies reported on the prevalence of various mental health problems. Six studies were conducted in the refugee sector. One study on 179 refugee service providers in South Korea (Kim, 2017) and one study on 31 refugee caregivers in the USA (Lusk & Terrazas, 2015) reported that about half of their study participants had symptoms of secondary traumatic stress. In a Swedish cross‐sectional survey, 44% of the social workers working with refugee children were suffering from psychological disturbance; in the comparison group of those working with other vulnerable children, only 34% were affected (J. Sundqvist, personal communication, January 30, 2018). Out of 12 staff members at a refugee centre in the UK, four were at higher risk of burnout and five of compassion fatigue (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011). In contrast, a survey conducted among 115 German and Austrian refugee aid workers reported that none of the participants scored high on the risk of burnout or compassion fatigue (Pell, 2013). Both studies found moderate or high levels of compassion satisfaction (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Pell, 2013). When Pell (2013) compared different groups of refugee aid workers, he found that social workers and other not psychologically trained workers had higher burnout values and somatic symptoms compared to psychologically trained workers. In the entire sample, 27% showed symptoms of global stress and depression and 37% reported symptoms of anxiety. Among another group of refugee aid workers from Germany, the prevalence of major depression (4.4%) was comparable to normative data (3.8%; Grimm et al., 2017).

Three studies reported on mental health problems in the homeless sector. In a sample of 245 frontline workers working with homeless individuals in Canada, Waegemakers Schiff and Lane (2016) found that 24% of the sample scored high on compassion fatigue and burnout. Furthermore, 36% were positively screened for post‐traumatic stress disorders. Still, 84% reported average or high levels of compassion satisfaction. In a former survey of 71 service providers for the homeless in the USA, 90% were reasonably satisfied with their jobs; however, one fourth experienced at least moderate levels of emotional exhaustion and one third were likely to look for a new job within the next year (Hagen & Hutchison, 1988). Among a sample of 18 caseworkers in a homeless shelter in the US, 39% scored high on burnout. Sample means regarding emotional exhaustion (M = 29) and depersonalisation (M = 13) were higher than those from normative data on social services (M = 21 and M = 7, respectively); means of personal accomplishment were virtually identical (Sutton‐Brock, 2013).

3.5. Coping strategies

One coping strategy was the maintenance of professional boundaries with clients (Ferris et al., 2016; Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Lakeman, 2011). Homeless sector workers emphasised the importance of being friendly, but not being friends with the clients (Lakeman, 2011). Also frequently described was the maintenance of clear boundaries between work and personal lives (Ferris et al., 2016; Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Kidd et al., 2007; Lakeman, 2011). These could be maintained by not dealing with work topics in personal life (Kidd et al., 2007). Further coping strategies consisted of having a good social life outside of work and sharing experiences with family members and friends or colleagues (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Kidd et al., 2007; Lusk & Terrazas, 2015). Three studies described practicing hobbies, such as exercise, reading, listening to music, mediating or just having time for oneself as being helpful (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Lakeman, 2011; Lusk & Terrazas, 2015). Three studies identified religious practices as a coping strategy (Ferris et al., 2016; Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Lusk & Terrazas, 2015).

Strategies mentioned only by studies conducted in the homeless sector included taking actions to reduce clients’ pain, accepting one's own boundaries of influence (Ferris et al., 2016), acknowledging small successes (Lakeman, 2011) and accepting client behaviours but not taking them personally (Kosny & Eakin, 2008). One study conducted among staff members of a refugee centre identified drinking alcohol as a coping strategy (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011), while another study explicitly stated that none of their interviewed caregivers working with refugees reported the use of alcohol or drugs as a coping strategy (Lusk & Terrazas, 2015). A Swedish survey compared coping strategies among social workers and police officers with and without experience working with unaccompanied asylum‐seeking refugee children. Social workers working with refugee children used the emotion‐focused strategies of escape avoidance, distancing and positive reappraisal more often than police officers and the problem‐focused strategy of planful problem solving less often. Still, social workers working with refugee children used planful problem solving more often than those without experience of working with refugee children (Sundqvist, Ghazinour et al., 2017). Pell (2013) found that emotion‐focused coping strategies were significantly associated with several stress symptoms, such as burnout, anxiety and depression among refugee aid workers (Table 2).

3.6. Interventions and needs

Only one of the studies included in this scoping review was intervention‐based. It examined the impact of an occupational therapy consultation model on the job satisfaction and self‐efficacy of case managers working in a homeless centre in the USA. The occupational consultant provided direct interventions to homeless clients as well as client assessments and treatment recommendations to case managers. The authors concluded that case managers’ job satisfaction and self‐efficacy improved when they were more actively seeking and utilising consultation services (Chapleau et al., 2011). Three studies emphasised the importance or need for staff in the refugee and homeless sector to receive external counselling (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Kidd et al., 2007; Lakeman, 2011) and supervision (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Lakeman, 2011; Robinson, 2014). In both sectors, studies also identified a need for training on dealing with violence and aggression (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011; Mowbray et al., 1996). Staff members of a UK refugee centre further emphasised the need for training on managing, benefits, housing, new policies and procedures and dealing with clients’ mental health (Guhan & Liebling‐Kalifani, 2011). The latter was also important to German refugee aid workers. They saw their greatest training needs in recognising the mental health problems of clients and learning about intervention strategies to help affected clients. These were rated by the workers as being more important than psychosocial support for themselves and learning about self‐care (Grimm et al., 2017). Frontline homeless workers wished for more support, for example, in the form of written manuals, visits to a homeless programme similar to their own (Mowbray et al., 1996), more team development, more support from their supervisors, additional relief staff and greater recognition of their needs (Waegemakers Schiff & Lane, 2016).

3.7. Quality assessment

The results of the methodological quality assessment are displayed in Table S3. Six studies had a score of 25% (*), nine studies had a score of 50% (**) and 10 studies reached a score of 75% (***). None of the studies met all criteria of the appraisal tool. Two of the mixed methods studies met all criteria in their qualitative component, but their quantitative and mixed methods components were of lower quality. Thus, none of the mixed methods studies reached an overall quality score of higher than 50%. The inter‐rater reliability for the quality assessment was found to be moderate (Cohen's Kappa = 0.53).

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first review that systematically mapped the working conditions of staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals. Common job demands identified were working in a bureaucratic system, high caseloads, the exposure to clients’ suffering and little experience of success in their work. Specific to the refugee sector were staffs’ experience of negative attitudes towards their work, including racism and discrimination. Maintaining professional boundaries with clients represented both a demand and a coping strategy. Deriving meaning from work and support from the team were important job resources. Staff frequently reported mental health problems; however, prevalence rates are difficult to compare due to the use of different instruments in the studies. Literature on the effectiveness of workplace health interventions was sparse.

According to the JD‐R model, occupational settings may have their own specific job demands and resources (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). We identified a variety of job demands and resources, which seem to be prevalent among staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals. These were related to the organisation of work, job content and social relations. The physical work environment only played a minor role, either because staff do not experience significant demands in this respect or it has largely remained unconsidered in research. Some important demands are directly related to problems of clients such as the encounter of clients’ suffering and the inability to change the situation of clients. This finding reflects the close relationships staff in social work hold with their refugee and homeless clients. Kosny and Eakin (2008) described this phenomenon as ‘putting clients first’, meaning that the problems of clients are rated as being more important than the workers’ own needs. They stated that this client‐centredness might be more acceptable in their workplaces, as it reflects the caring character of social service organisations working with marginalised clients.

We identified diverse results on the mental health problems of staff in the refugee and homeless sector. For example, the prevalence of burnout ranged from 0%–39%. These diverse results could be explained by the heterogeneity of studies, the use of different instruments to measure certain mental health problems, different time frames, varying study samples and limited methodological quality. Interestingly, several studies in our review showed that staff in the refugee and homeless sector had a high job or compassion satisfaction, regardless of whether or not they reported job demands and mental health problems (e.g. Lusk & Terrazas, 2015). Similarly, a review of studies on child welfare and social work samples identified a coexistence of high job satisfaction and emotional exhaustion (Stalker et al., 2007). These findings could support the proposition of the JD‐R model that two different psychological processes exist. While job demands are related to strain and health problems, job resources influence motivation (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). Accordingly, high job demands and high job resources of staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals could lead to considerable strain and high motivation (e.g. job satisfaction) at the same time. However, the model further describes an interaction between job demands and resources in the sense that job resources may buffer the negative effect of job demands on strain (Bakker & Demerouti, 2007). In this case, one would assume that high job resources would decrease levels of strain. These effects and associations between job demands, resources and mental health need to be further investigated among staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals. Studies included in this review showed inconsistent results and were difficult to compare as they nearly all examined different predictors and outcome parameters.

Most of the coping strategies reported by staff members in social work in the included studies can be assigned to emotion‐focused coping strategies. This includes the most frequently mentioned strategies: distancing from work in personal life, engaging in hobbies and religious practices and seeking social support for emotional reasons. Folkman and Lazarus (1980) found that problem‐focused coping was used more often when a situation was appraised by a person as changeable whereas emotion‐focused coping was used more often when a situation was appraised as unchangeable. Therefore, it could be discussed that staff members regard some of their job demands as unchangeable. This could be assumed in particular for demands related to the political and structural context such as poor financial resources or the inability to change the situation of clients. Emotion‐focused strategies are often said to be less effective than problem‐focused strategies. But it is also argued that the effectiveness rather depends on the specific strategy employed and situational characteristics such as the type of stressor (Baker & Berenbaum, 2007; Penley, Tomaka, & Wiebe, 2002). Our results are mainly based on descriptions from qualitative studies. More research should examine the effectiveness of these coping strategies to develop adequate recommendations and support for staff members in social work with refugees and homeless individuals.

4.1. Implications for policy and practice

Based on our results, several implications can be derived at the political, organisational and individual level. Our review revealed that staff members in social work with refugees and homeless individuals struggle under high workloads and caseloads. Politicians and managers should consider increasing the number of professionals in these social services as well as reducing the number of clients for which an employee is responsible. This could ensure high‐quality services for clients and also increase the motivation of staff members. The feeling of not being able to care for clients adequately can be a source of ongoing frustration. To further improve working conditions of staff, more financial resources should be provided to these growing sectors and bureaucratic obstacles should be reduced. Another important task would be to openly communicate and fight racism in institutions and in public. In the refugee sector, more interpreters seem to be needed to facilitate adequate communication of staff members with clients.

As an attempt to increase the control and decision latitude of staff, managers should involve staff in their processes of decision‐making. A major emotional demand for staff members is to frequently encounter clients’ suffering and traumatic histories. It is important that staff members have the opportunity to talk about the emotional impact of their work, not only to colleagues, family members and friends, but also to a qualified supervisor. Therefore, organisations should provide regular sessions of group supervisions or even possibilities of an individual supervision or external counselling. Such offers have already been rated as very helpful by staff members in these sectors (Lakeman, 2011; Robinson, 2014).

Furthermore, social service organisations should provide possibilities for ongoing training and staff members should take advantage of training offers. Training on prevention of and dealing with violent incidents as well as mindfulness and yoga interventions could be important aspects (Crowder & Sears, 2017; Gregory, 2015). A common problem of staff members in social work is that they are emotionally involved with their clients, which exposes them to a higher risk of burnout (Miller et al., 1995). Therefore, more information on how to maintain boundaries with clients and boundaries between working and private life could be useful.

4.2. Strengths and limitations

This scoping review followed a systematic approach and methodological framework which assured high quality throughout the process of conducting this review. It involved an in‐depth literature search using seven electronic databases with no time limitation, also identifying grey literature and including several study languages. A further strength was the conduction of a quality assessment allowing for conclusions on the methodological depth of research. The scoping review proved to be an effective design for our study as, comparatively, a lot of qualitative and mixed‐method research was conducted in this field which could be included in this type of review.

The title/abstract screening was only conducted by one reviewer due to restricted resources. To confine this limitation in the study selection process, unclear titles/abstracts were discussed with the research team. Methods such as the applied instruments varied greatly in the studies included in this review. This limited the comparability of studies. Furthermore, the methodological quality of studies varied and was only low or moderate for the majority of studies (score of 25% and 50%). All but one study had a cross‐sectional design. Therefore, the results concerning associated factors need to be interpreted with particular caution. In addition, some difficulties concerning the study population need to be taken into account when interpreting the results of this review: (a) Most studies involved several occupational groups (for example, the whole workforce of a refugee or homeless organisation), which we considered for this review when they also included staff members in social work; (b) Work tasks and qualifications might vary between countries; (c) Work tasks and qualifications of the study participants were often not clearly described in studies. These aspects might limit the comparability between the results of the studies and the generalisability of the results for the target population.

5. CONCLUSION

The results of this scoping review suggest that social work with refugees and homeless individuals are highly demanding areas of work. The prevalence of mental health problems as a result of the job demands encountered, however, remains unclear from the existing literature and should be further investigated. Noticeably, staff members in these fields have personal and job resources at their disposal and reported good job satisfaction. It needs to be further investigated how these resources can be strengthened and how job demands can be reduced by effective workplace health interventions. On the basis of this scoping review, we would not recommend carrying out a systematic review, as the research is still relatively sparse and mainly of low or moderate methodological quality. Instead, this indicates the need for future studies with sound qualitative and quantitative designs, but also, in particular, longitudinal studies in order to establish empirical evidence on these topics.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

Supporting information

Wirth T, Mette J, Prill J, Harth V, Nienhaus A. Working conditions, mental health and coping of staff in social work with refugees and homeless individuals: A scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2019;27:e257–e269. 10.1111/hsc.12730

Funding information

This work was supported by the Institution for Statutory Accident Insurance and Prevention in the Health and Welfare Services (BGW), Hamburg, Germany. The funds were provided by a non‐profit organisation that is part of the social security system in Germany. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Anderson, D. G. (2000). Coping strategies and burnout among veteran child protection workers. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24, 839–848. 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00143-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. , & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baker, J. P. , & Berenbaum, H. (2007). Emotional approach and problem‐focused coping: A comparison of potentially adaptive strategies. Cognition and Emotion, 21, 95–118. 10.1080/02699930600562276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A. B. , & Demerouti, E. (2007). The Job Demands‐Resources model: State of the art. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 22, 309–328. 10.1108/02683940710733115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, C. , Maar, K. , Otto, H.‐U. , Schaarschuch, A. , & Schrödter, M. (2009). Burnout als Folge restringierender Arbeitsbedingungen? Ergebnisse einer Studie aus der Sozialpädagogischen Familienhilfe In Beckmann C., Otto H.‐U., Richter M., & Schrödter M. (Eds.), Neue Familialität als Herausforderung der Jugendhilfe Sonderheft 9 (pp. 194–208). Lahnstein: Verlag neue praxis. [Google Scholar]

- Beebe, J. (2016). Compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction: Experiences of helping professionals in the homeless workforce: A project based upon an investigation at Boston Healthcare for the Homeless, Boston, Massachusetts. (Masters Thesis), Smith College School for Social Work, Northampton, MA. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.smith.edu/theses/1720.

- Blomberg, H. , Kallio, J. , Kroll, C. , & Saarinen, A. (2015). Job stress among social workers: Determinants and attitude effects in the Nordic countries. British Journal of Social Work, 45, 2089–2105. 10.1093/bjsw/bcu038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borritz, M. , Rugulies, R. , Bjorner, J. B. , Villadsen, E. , Mikkelsen, O. A. , & Kristensen, T. S. (2006). Burnout among employees in human service work: Design and baseline findings of the PUMA study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 34, 49–58. 10.1080/14034940510032275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapleau, A. , Seroczynski, A. D. , Meyers, S. , Lamb, K. , & Haynes, S. (2011). Occupational therapy consultation for case managers in community mental health: Exploring strategies to improve job satisfaction and self‐efficacy. Professional Case Management, 16, 71–79. 10.1097/NCM.0b013e3181f0555b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, D. , Edwards, D. , Hannigan, B. , Fothergill, A. , & Burnard, P. (2005). A systematic review of stress among mental health social workers. International Social Work, 48, 201–211. 10.1177/0020872805050492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crowder, R. , & Sears, A. (2017). Building resilience in social workers: An exploratory study on the impacts of a mindfulness‐based intervention. Australian Social Work, 70, 17–29. 10.1080/0312407X.2016.1203965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daudt, H. M. L. , Mossel, C. V. , & Scott, S. J. (2013). Enhancing the scoping study methodology: A large, inter‐professional team's experience with Arksey and O'Malley's framework. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 48 10.1186/1471-2288-13-48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drüge, M. , & Schleider, K. (2016). Psychosoziale Belastungen und Beanspruchungsfolgen bei Fachkräften der Sozialen Arbeit und Lehrkräften. Ein Vergleich von Merkmalen, Ausprägungen und Zusammenhängen [Psychosocial burden and strains of social workers and teachers. A comparison of characteristics, manifestations and interrelations]. Soziale Passagen, 8, 293–310. 10.1007/s12592-016-0235-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FEANTSA, & Fondation Abbé Pierre (2018). Third overview of housing exclusion in Europe 2018. Brussels, Paris: Retrieved fromhttps://www.feantsa.org/download/full-report-en1029873431323901915.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Ferris, L. J. , Jetten, J. , Johnstone, M. , Girdham, E. , Parsell, C. , & Walter, Z. C. (2016). The florence nightingale effect: Organizational identification explains the peculiar link between others' suffering and workplace functioning in the homelessness sector. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 16 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figley, C. R. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview In Figley C. R. (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (pp.e257–20). New York, NY, London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Filsinger, D. (2017). Soziale Arbeit mit Flüchtlingen. Strukturen, Konzepte und Perspektiven (WISO Diskurs 14/2017). Bonn: Friedrich‐Ebert‐Stiftung, Abteilung Wirtschafts‐ und Sozialpolitik. [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S. , & Lazarus, R. S. (1980). An analysis of coping in a middle‐aged community sample. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 21, 219–239. 10.2307/2136617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman, S. , Lazarus, R. S. , Dunkel‐Schetter, C. , DeLongis, A. , & Gruen, R. J. (1986). Dynamics of a stressful encounter: Cognitive appraisal, coping, and encounter outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 992–1003. 10.1037/0022-3514.50.5.992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis, L. E. (2000). Conflicting bureaucracies, conflicted work: Dilemmas in case management for homeless people with mental illness. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 27, 97–112. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, A. (2015). Yoga and mindfulness program: The effects on compassion fatigue and compassion satisfaction in social workers. Journal of Religion & Spirituality in Social Work: Social Thought, 34, 372–393. 10.1080/15426432.2015.1080604 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grimm, T. , Georgiadou, E. , Silbermann, A. , Junker, K. , Nisslbeck, W. , & Erim, Y. (2017). Psychische und kontextuelle Belastungen, Motivationsfaktoren und Bedürfnisse von haupt‐ und ehrenamtlichen Flüchtlingshelfern [Distress, main burdens, engagement motivators and needs of fulltime and volunteer refugee aid workers]. Psychotherapie · Psychosomatik · Medizinische Psychologie, 67, 345–351. 10.1055/s-0043-100096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guhan, R. , & Liebling‐Kalifani, H. (2011). The experiences of staff working with refugees and asylum seekers in the United Kingdom: A grounded theory exploration. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies, 9, 205–228. 10.1080/15562948.2011.592804 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen, J. L. , & Hutchison, E. (1988). Who's serving the homeless? Social Casework, 69, 491–497. [Google Scholar]

- Hajji, R. (2018). Burnout‐Gefährdung von Sozialarbeiter_innen in Aufnahmeeinrichtungen für Geflüchtete. Sozial Extra, 42, 61–65. 10.1007/s12054-018-0028-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khera, M. L. K. , Harvey, A. J. , & Callan, M. J. (2014). Beliefs in a just world, subjective well‐being and attitudes towards refugees among refugee workers. Social Justice Research, 27, 432–443. 10.1007/s11211-014-0220-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd, S. A. , Miner, S. , Walker, D. , & Davidson, L. (2007). Stories of working with homeless youth: On being “mind‐boggling”. Children and Youth Services Review, 29, 16–34. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2006.03.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y. J. (2017). Secondary traumatic stress and burnout of North Korean refugees service providers. Psychiatry Investigation, 14, 118–125. 10.4306/pi.2017.14.2.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosny, A. A. , & Eakin, J. M. (2008). The hazards of helping: Work, mission and risk in non‐profit social service organizations. Health, Risk & Society, 10, 149–166. 10.1080/13698570802159899 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lakeman, R. (2011). How homeless sector workers deal with the death of service users: A grounded theory study. Death Studies, 35, 925–948. 10.1080/07481187.2011.553328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S. , & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D. , Colquhoun, H. , & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, C. , King, R. , & Chenoweth, L. (2002). Social work, stress and burnout: A review. Journal of Mental Health, 11, 255–265. 10.1080/09638230020023642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lusk, M. , & Terrazas, S. (2015). Secondary trauma among caregivers who work with Mexican and Central American refugees. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 37, 257–273. 10.1177/0739986315578842 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden, P. , Campbell, A. , & Taylor, B. (2015). Resilience and burnout in child protection social work: Individual and organisational themes from a systematic literature review. British Journal of Social Work, 45, 1546–1563. 10.1093/bjsw/bct210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miller, K. , Birkholt, M. , Scott, C. , & Stage, C. (1995). Empathy and burnout in human service work: An extension of a communication model. Communication Research, 22, 123–147. 10.1177/009365095022002001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molnar, B. E. , Sprang, G. , Killian, K. D. , Gottfried, R. , Emery, V. , & Bride, B. E. (2017). Advancing science and practice for vicarious traumatization/secondary traumatic stress: A research agenda. Traumatology, 23, 129–142. 10.1037/trm0000122 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mowbray, C. T. , Thrasher, S. P. , Cohen, E. , & Bybee, D. (1996). Improving social work practice with persons who are homeless and mentally ill. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 23, 3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Pell, M. (2013). Sekundärtraumatisierung bei Helferinnen im Umgang mit traumatisierten Flüchtlingen. (Diplomarbeit), Universität Wien, Wien. Retrieved from http://othes.univie.ac.at/29474/

- Penley, J. A. , Tomaka, J. , & Wiebe, J. S. (2002). The association of coping to physical and psychological health outcomes: A meta‐analytic review. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 25, 551–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluye, P. , Robert, E. , Cargo, M. , Bartlett, G. , O'Cathain, A. , Griffiths, F. , … Rousseau, M. C. (2011). Proposal: A mixed methods appraisal tool for systematic mixed studies reviews. Retrieved from http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com. Archived by WebCite® at http://www.webcitation.org/5tTRTc9yJ

- Robinson, K. (2014). Voices from the front line: Social work with refugees and asylum seekers in Australia and the UK. British Journal of Social Work, 44, 1602–1620. 10.1093/bjsw/bct040 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schepman, S. B. , & Zarate, M. A. (2008). The relationship between burnout, negative affectivity and organizational citizenship behavior for human services employees. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2, 74–87. 10.1999/1307-6892/3080 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schutt, R. K. , & Fennell, M. L. (1992). Shelter staff satisfaction with services, the service network, and their jobs: The influence of disposition and situation. Current Research on Occupations and Professions, 7, 177–200. [Google Scholar]

- Söderfeldt, M. , Söderfeldt, B. , & Warg, L.‐E. (1995). Burnout in social work. Social Work, 40, 638–646. [Google Scholar]

- Stalker, C. A. , Mandell, D. , Frensch, K. A. , Harvey, C. , & Wright, M. (2007). Children welfare workers who are exhausted yet satisfied with their jobs: How do they do it? Child & Family Social Work, 12, 182–191. 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00472.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist, J. , Ghazinour, M. , & Padyab, M. (2017). Coping with stress in the forced repatriation of unaccompanied asylum‐seeking refugee children among Swedish police officers and social workers. Psychology, 8, 97–118. 10.4236/psych.2017.81007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist, J. , Hansson, J. , Ghazinour, M. , Ogren, K. , & Padyab, M. (2015). Unaccompanied asylum‐seeking refugee children's forced repatriation: Social workers' and police officers' health and job characteristics. Global Journal of Health Science, 7, 215–225. 10.5539/gjhs.v7n6p215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundqvist, J. , Padyab, M. , Hurtig, A.‐K. , & Ghazinour, M. (2017). The association between social support and the mental health of social workers and police officers who work with unaccompanied asylum‐seeking refugee children's forced repatriation: A Swedish experience. International Journal of Mental Health, 47, 3–25. 10.1080/00207411.2017.1400898 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sutton‐Brock, C. D. (2013). Homelessness: an evaluation of resident self‐efficacy and worker burnout within county homeless shelters (Dissertation). Capella University, Ann Arbor, MI. Retrieved from https://search.proquest.com/docview/1427339277 (3587586).

- UNHCR . (2018). Global trends. Forced displacement in 2017. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org/statistics

- Waegemakers Schiff, J. , & Lane, A. (2016). Burnout and PTSD in workers in the homeless sector in Calgary. Retrieved from http://calgaryhomeless.com/content/uploads/Calgary-Psychosocial-Stressors-Report.pdf

- Yürür, S. , & Sarikaya, M. (2012). The effects of workload, role ambiguity, and social support on burnout among social workers in Turkey. Administration in Social Work, 36, 457–478. 10.1080/03643107.2011.613365 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials