Summary

Obesity has increased to an epidemic level in the Gulf States. This systematic review is the first to explore the scientific evidence on correlates and interventions for overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 25) or weight‐related behaviours in the region. A systematic search of peer‐reviewed articles was conducted using PubMed and PsycINFO. Ninety‐one studies were eligible for this review including 84 correlate studies and seven intervention studies. Correlate studies of overweight focused on sociodemographic factors, physical activity, and dietary habits. Low physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and unhealthy dietary habits were associated with overweight. The most‐reported sociodemographic correlates of overweight were increased age, being married, low education, urban residence, and unemployment. Correlate studies of physical activity and dietary behaviours mostly focused on sociodemographic variables. Being female and increased age (the latter less consistently) were associated with low physical activity. Interventions were very heterogeneous with respect to the target group, intensity, and behavioural strategies used. The effectiveness of interventions was difficult to evaluate because of the chosen study design or outcome measure, the small sample size, or high attrition rate. Few studies have investigated sociocognitive and environmental determinants of weight‐related behaviours. Such information is crucial to developing health promotion initiatives that target those weight‐related behaviours.

Keywords: adults, correlate studies, intervention studies, Middle East, overweight/obesity

Abbreviations

- BMI

body mass index

- FV

fruit and vegetable

- PA

physical activity

- WC

waist circumference

1. INTRODUCTION

Levels of overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥ 25) and obesity (BMI ≥ 30) have been increasing significantly during the last four decades. This increase has been particularly dramatic in the Gulf States, including Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.1 In the past, Arabs associated overweight/obesity with wealth and prosperity for men and with health and fertility for women.1 However, these views are changing, and obesity is currently perceived as a very serious health issue and risk factor for many comorbidities.2 The estimated prevalence of overweight among adults in Saudi Arabia has increased from 38.1% in 1975 to 69.7% in 2016.3 In Saudi Arabia, 20 000 people die each year from diseases associated with overweight and obesity.4 The Saudi government is spending over 19 billion riyals (€4.5 billion) annually to fight the burden of these diseases.4 The prevalence and associated health care costs of obesity are similar to other Gulf States.3 Fortunately, overweight and obesity are among the most preventable causes of morbidity and mortality.5 Therefore, these costs and negative health effects can be reduced if more investments are made in effective prevention strategies. To develop effective behavioural interventions, it is essential to examine the potential determinants of obesity or weight‐related behaviours and to review existing interventions targeting these weight‐related behaviours.

There have been several systematic reviews and “umbrella reviews” (reviews that give an overview of the systematic reviews conducted in an area) on correlates of overweight/obesity, including reviews on (correlates of) dietary behaviours, physical activity (PA), and sedentary lifestyle.6, 7, 8, 9 Moreover, there are some systematic reviews of interventions on diet and PA for the prevention of obesity in adults.10, 11 However, these reviews were directed at, and/or mainly covered, studies in the United States, Australia, or Europe. Although there are some systematic reviews on the prevalence of overweight and obesity in the Gulf States,12, 13 to our knowledge, reviews on correlates and interventions in that region do not exist. This knowledge gap is especially worrisome because the correlates and active ingredients of interventions in the Gulf States may differ considerably from those in Western countries. Such a review would increase our knowledge of the most important contributing factors to, and determinants of, overweight/obesity and weight‐related behaviours in the Gulf States. This knowledge would help health professionals and policymakers to develop environmental and/or behavioural modification strategies and effective interventions. The purpose of this study is to perform a systematic literature review of the correlates of overweight/obesity and weight‐related behaviours in the Gulf States and of interventions for overweight/obesity among adults in this region.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search strategy and eligibility criteria

A comprehensive, systematic search of peer‐reviewed articles published up until 12 September 2017 was conducted using the databases PubMed and PsycINFO. The search strategy involved a combination of MeSH terms in PubMed, thesaurus terms in PsycINFO, and title and abstract for all terms (see Table S1 for the search strategy in PubMed).

To be included, studies had to be conducted in the Gulf States. Studies on correlates of overweight and/or obesity were included, as were studies of correlates of PA, dietary behaviours, and sedentary lifestyle (eg, screen viewing). Second, we included evaluation studies of either overweight or obesity interventions and related interventions such as diet or PA interventions. Studies about nutrients such as protein and fat were not included. We also excluded studies that focused on a specific population (eg, patients with any chronic disease or pregnant women), studies that were not empirical, qualitative and case studies, studies involving treatments such as drugs or surgery, and studies not published in peer‐reviewed scientific journals. The current review focuses on adults (18 y or more). A second review, conducted using the same methodology, on the correlates of dietary behaviour, PA, and overweight/obesity in children and adolescents will be published elsewhere.

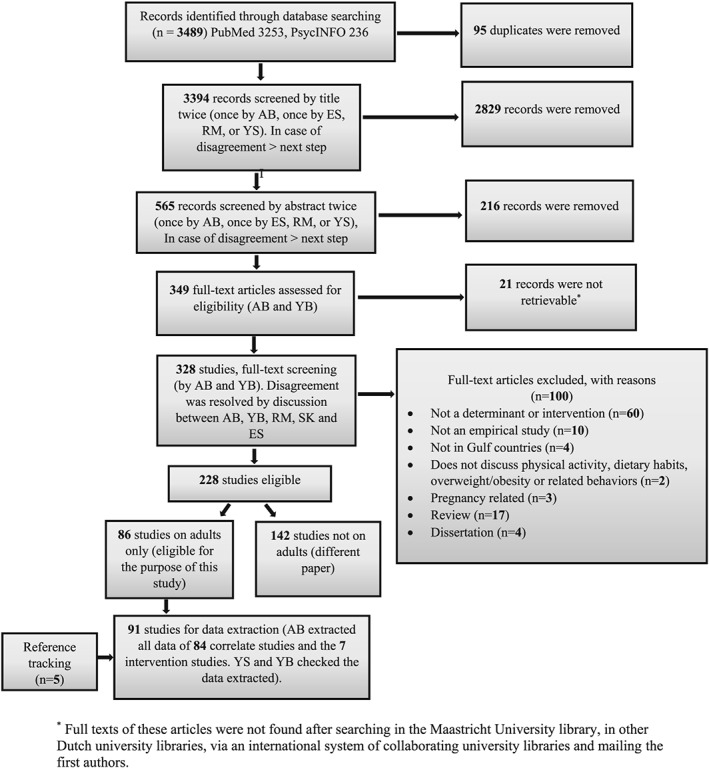

A total of 3489 studies (3253 in PubMed and 236 in PsycINFO) were found, which ultimately resulted in 91 articles eligible for data extraction (see Figure 1 for the procedure of the literature search, and see Tables 1, 2, 3, 4 for the data extraction forms developed by the authors).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search

Table 1.

Descriptive summary of correlate studies of overweight and obesity

| Author (Year) | Country | Area | Age, Range in Years and Mean (SD) | Sample Size | Participants | Correlate Measure | Outcome Measure | By What Measure is the Determinant Evaluated | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sayegh et al (2016)14 | Qatar | ‐ | 18‐64, 37.4 (11.7) | 549 | Qatari females | Physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | There was no statistically significant difference among BMI levels with respect to physical activity. |

| Bin Horaib et al (2013)15 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 34.12 (7.25) | 10 229 | Military male personnel | Sociodemographic factors, smoking, dietary habits, and physical activity | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Increased age, more years of education, and family history of diabetes or hypertension were related to higher BMI, while higher military rank, smoking, eating fruits more than twice per week, and strenuous physical activity were related to lower BMI. |

| Al‐Nozha et al (2007)16 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 30‐70, 46.3 (11.50) | 17 395 | Saudis (8297 males and 9098 females) | Physical activity | BMI and waist circumference (WC) | National Epidemiological Health Survey by researcher | Individuals who were physically active showed lower values of BMI and WC. |

| Al‐Nozha et al (2005)17 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 30‐70 | 17 232 | Saudis (8215 males and 9008 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Overweight was higher among males, while obesity was higher among females. Urban residents were more obese compared with Saudis living in rural areas. Obesity is the highest among Saudis living in the eastern region of Saudi Arabia, while the lowest rate was observed in the southern region. Regarding age group, 40‐49 were most obese, and 60‐70 were most overweight. |

| AlAteeq and AlArawi (2014)18 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 39.2 (8.91) | 322 | Clinicians (127 males and 195 females) | Sociodemographic factors, dietary habits, and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Females had lower BMI than males. No significant correlation was found between dietary habits and BMI. Higher levels of physical activity were associated with lower BMI. Nurses and pharmacists had a significantly lower BMI compared with physicians. |

| Allam et al (2012)19 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 21.06 (1.85) | 194 | University medical students (94 males and 100 females) | Sociodemographic factors, dietary habits, and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Male students showed higher rates of obesity than females. A positive correlation was observed between the median caloric intake and BMI. Inactivity was associated with increased median caloric intake and BMI. High intakes of carbohydrates and animal foods and low intakes of fibre, minerals, and vitamins coupled with low physical activity were associated with overweight and obesity among students. |

| Al Qauhiz (2010)20 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 22‐24, 20.78 (3.01) | 799 | Female university students | Sociodemographic factors and dietary habits | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Being married, presence of obesity among family members, and frequency of soft drinks consumption were related to obesity. |

| Al‐Baghli et al (2008)21 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 30 and older | 195 874 | Saudis (99 946 males and 95 905 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | The highest prevalence of obesity was detected in the age group 50‐59 y. Obesity increased with age. It was higher among women than men, higher in housewives, higher among married subjects, higher among the less well educated, those with low income, and those who were less physically active. |

| Rasheed (1998)22 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 29.28 (7.70) | 144 | Saudi females | Sociodemographic factors, dietary habits, and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | High consumption of calorie‐rich diets, the traditional system of food hospitality, low physical activity, lack of awareness regarding obesity status, and attitudes and behaviours related to eating (antecedents of eating such as emotional states of stress, anger, and boredom) were the main risk factors for female obesity. Obese participants were less likely to eat at fixed times during the day and more often indulged in eating while watching TV. |

| Almajwal (2015)23 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 362 | Non‐Saudi female nurses | Sociodemographic factors, dietary habits, and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Low physical activity was related to high BMI. Nurses who worked shift duty had significantly higher BMIs compared with day shift nurses. Nurses who rarely ate breakfast and meals and often ate fast food were more likely to be overweight or obese. |

| Almajwal (2016)24 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 18 and older | 395 | Non‐Saudi female nurses | Dietary habits, emotion, and stress | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | BMI was significantly correlated with restrained eating style (the tendency to restrict food intake in order to control body weight), emotional eating style (the tendency to cope with negative emotions), and stress. |

| Khalaf et al (2013)25 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 20.4 (1.50) | 663 | Female university students | Physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | High physical activity was related to high BMI. |

| Samara et al (2015)26 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 18‐22, 20 (0.70) | 94 | Female university students | Sedentary behaviour | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | High sedentary behaviour was associated with high BMI. |

| El Hamid (2014)27 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐28, 20.78 (1.76) | 400 | Female university students | Home breakfast skipping | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Home breakfast eaters had a significantly higher BMI compared with home breakfast skippers. |

| Al‐Otaibi (2013)28 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 20‐56 | 242 | Saudis (118 males and 124 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Males had higher BMI levels than females. |

| Al‐Otaibi (2013)29 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 21.74 (1.55) | 960 | Female university students | Fruit and vegetable consumption | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Females who consumed less than five servings per day group had higher BMI than the five or more servings per day group. |

| Khalaf et al (2014)30 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18 and older, 20.4 (1.50) | 663 | Female university students | Sociodemographic factors, dietary habits, and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Social factors positively associated with high BMI were the presence of obese parents and siblings, being married, high number of sisters, high level of father's education, more frequent intake of French fries/potato chips (greater than three times per week), and low physical activity levels. |

| Al‐Rethaiaa et al (2010)31 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐24 | 357 | Male university students | Dietary habits | Obesity “BMI” “VFL” | Self‐administered survey | Eating with family and frequent snacking were found to be related to high BMI. Visceral fat level (VFL) was inversely correlated with the frequency of both eating with family and date consumption. |

| Al‐Nuaim et al (1997)32 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 20 and older, 35.8 (14.27) | 10 651 | Saudis (50.8% males and 49.2% females) | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | The prevalence of obesity was higher in females than males, lower in subjects living in rural areas with traditional lifestyles than those in more urbanized environments, and increased with increased age, lower education, and income. |

| Khalid (2007)33 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐60 | 438 | Married, nonpregnant females | Sociodemographic factors and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” and abdominal obesity | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Increased age, total obesity, and multiple pregnancies were significantly associated with a higher prevalence of abdominal obesity. Low educational level and low physical activity were associated with higher abdominal obesity. |

| Al Dokhi and Habib (2013)34 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐72, 36.91 (15.22) | 411 | Saudis (300 males and 111 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Males had a significantly higher prevalence of overweight compared with females. Females had a significantly higher prevalence of class II and III obesity compared with males. |

| Al‐Shahrani Al‐Khaldi (2011)35 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 36.2 (13.60) | 429 | Patients attended health care clinics (217 males and 212 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender,” dietary habits, and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Records of people attending health promotion clinics by researcher | Obesity was higher among women than men and among those above 45 y old. |

| Abdel‐Megeid et al (2011)36 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 21.1 (2.80) | 312 | University students (132 males and 180 females) | Sociodemographic factors, dietary habits, and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Males had a higher percentage of overweight and obesity when compared with females. Increased fat consumption was correlated with high BMI. High economic status was correlated with high BMI. Low consumption of fibre, grains, vegetables, fruits, and beans and low exercise level of both genders were correlated with high BMI. |

| Aboul Azm (2010)37 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐22, 20.17 (1.30) | 300 | Saudi female nursing students | Dietary habits and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | More obese students were taking meals irregularly, snacking more frequently, and drinking more beverages and coffee/tea as compared with non‐obese students. Not having breakfast in the morning and rarely eating green, red, or yellow coloured vegetables, eating fried food, eating fast food, eating with friends, and eating out were practices associated with obesity. In addition, obese students had a lower physical activity level. |

| Al‐Shammari et al (1994)38 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 32.2 (11.70) | 1385 | Saudi females | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Poorly educated housewives more than 45 y old, particularly divorced, or widowed ones had higher BMI than others. BMI increased with age and multiple pregnancies. Participants living in rural areas had higher BMIs than those living in urban areas. |

| Albarrak et al (2016)39 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 18 and older | 448 | University students (177 males and 271 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Prevalence of overweight and obesity was higher among male compared with female students. |

| Albawardi et al (2016)40 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 18‐58 | 420 | Saudi females working in office jobs | Sociodemographic and psychosocial factors | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by trained staff | Overweight/obesity was associated with increased age (over 35 y old), being married, having at least one child, having an education level above high school, having a family income of less than 10 000 Saudi riyals (SR), and working in the public sector (as compared with private sector). Physical activity, social support, and general self‐efficacy were not found to be associated with being overweight or obese. |

| Alodhayani et al (2017)41 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐25, 20.7 (2.33) | 408 | University medical students (224 males and 184 females) | Sociodemographic factors, sleep disturbances, and sleep duration | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements were taken | Male subjects had higher BMI than females. Normal‐weight subjects had a higher‐frequency percentage who reported in losing weight (30.6%) by performing exercise (25.7%) and diet (27%) on a regular basis compared with overweight and obese subjects. Also, results showed that there was an association between lack of sleep and reported weight gain, which can lead to obesity. The duration of sleeping between 5 and 6 h was linked to weight gain. There was a correlation between obesity and disturbance of sleep. Overweight and obese subjects had higher sleep disturbances such as watching television, lying down after lunch, and sitting and reading than normal‐weight subjects. |

| Azzeh et al (2017)42 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 18‐60, 29.1 (8.5) | 2548 | Saudis (188 males and 224 females) | Sociodemographic factors | BMI, WC, total body fat, and visceral fat level (VFL) | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by trained staff | The prevalence of obesity and overweight was higher in men than in women. Waist circumference and visceral fat level were higher in men than in women, but the mean total body fat percentage was higher in females than in males. |

| Al‐Tannir et al (2016)43 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18 and older, 33.3 (11.8) | 1369 | Saudi citizens | Sleep disturbances | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Obesity was significantly associated with sleep disturbances. High levels of BMI were related to short sleep duration. |

| Saeed et al (2017)44 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐24, 21.2 (1.2) | 292 | University students (146 males and 146 females) | Sociodemographic factors + physical activity | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by trained staff | Males had a higher prevalence of obesity than females. Subjects with chronic diseases were more prone to be obese. Family history of obesity was significantly associated with obesity. No significant association was found between physical activity and obesity. |

| Allafi and Waslien (2014)45 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 18‐59, 26 (7.90) | 1370 | Kuwaiti males and females | Physical activity “inactivity” | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | High physical inactivity patterns were associated with high levels of BMI. |

| Al Zenki et al (2012)46 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 20‐86, M 39.1 (0.90) and F 40.9 (0.70) | 1830 | Kuwaiti adults (459 males and 533 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” | Overweight and obesity “WC and BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Waist circumferences (WC) of males were significantly higher than those of females; however, the BMI and body fat levels of females were significantly higher than those of males. Males had a higher percentage of overweight than females; however, a significantly higher percentage of females were obese compared with males. |

| Al‐Isa (2004)47 | Kuwait | Urban | 20 and older | 461 | Female teachers | Sociodemographic factors, physical activity, obesity history, and dental status | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Factors found to be significantly associated with overweight, and obesity included increased age, being married, parents living at home, parental obesity, high number of obese relatives, low exercise, and low dental status. |

| Al‐Isa (2011)48 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 787 | Kuwaiti university students (378 males and 409 females) | Sociodemographic factors and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Obesity was higher among males than females, 13% to 10.5%, respectively. High levels of BMI were associated with low physical activity. |

| Ramadan and Barac‐Nieto (2001)49 | Kuwait | Urban | 18‐37, 28.32 (1.83) | 45 | Male office workers or students | Physical activity, fitness level, and body composition | Obesity “BMI, skin folds, body fat content, and fat percentage” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Sedentary and minimally physically active groups had higher body weight, BMI, skin folds, body fat content, and fat percentage. |

| Badr et al (2013)50 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 50 and older, 64.3 (9.30) | 2443 | Elderlies (948 males and 1495 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | In general, higher age was related to more overweight and obesity. However, Kuwaitis aged 50‐59 were 1.7 and 2.2 times more likely to be overweight and obese, respectively, compared with those aged 70 or older. Married individuals had 2.3 times higher risk of being overweight or obese than nonmarried individuals. Women were 3.6 times more likely to suffer from obesity than were men. |

| Musaiger et al (2014)51 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 19‐26, 21 (3) | 530 | University students (203 males and 327 females) | Sociodemographic factors, dietary habits, and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Students with obesity were more likely to face barriers to healthy eating than other students. Also, males with obesity faced more significant personal barriers to physical activity than other males, such as lack of interest in being physically active, skills, and motivation to exercise. There were no significant differences between women with obesity and women who are not obese regarding barriers to healthy eating and physical activity. |

| Al‐Isa (1999)52 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 515 | Kuwaiti male college students | Sociodemographic factors, dental status, obesity history dietary habits, and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Increased age, poor dental status, having a chronic disease, high number of obese brothers, high number of obese relatives, high parental obesity, low educational level, low grade point average (GPA), low high school GPA, high number of persons living at home, low monthly family income, low physical activity, low practice of sports, number of children, poor health status, dieting, number of times dieted, feeling tired, and needing special nutritional programmes were the factors found to be associated with overweight and obesity. |

| Al‐Asi (2003)53 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 3282 | Kuwait oil company employees (2804 males and 478 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Males showed a higher level of overweight and obesity (79%) than females (56%). Field workers had a higher level of overweight and obesity (78%) than office workers (72%). |

| Al‐Kandari (2006)54 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 21‐77 | 424 | Kuwaitis (212 males and 212 females) | Sociodemographic factors, sociocultural characteristics, dietary habits, and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Findings showed that there was a negative association between BMI and general physical activity and physical activity at work. Also, there was a positive association between BMI and some social variables, including number of relatives living in the same household and number of families living in the same household, while no relationship was found with the number of children in general. But when the data are divided by gender, results showed that there was a significant association between BMI and number of children in women only. There was a positive association between BMI and how often one ate at a restaurant weekly, having a cook in the family, and degree of preferring salt in food. |

| Al Rashdan and Al‐Nesef (2010)55 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 20‐65 | 2280 | Kuwaitis (918 males and 1362 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Overweight and obesity rates were higher in women compared with men. Overweight and obesity were more prevalent in the older age group, aged 55 to 64 y. |

| Al‐Isa (2003)56 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 5502 | Kuwaitis (2626 males and 2876 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Longer period of study, increased age, urban region, low education, being married, and not working were associated with higher BMI. |

| Ramadan and Barac‐Nieto (2003)57 | Kuwait | Urban | 33.43 (1.30) | 156 | Kuwaitis (72 males and 84 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” and physical activity | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Sedentary and low‐frequency physical activity groups of both genders had higher BMI than the active higher‐frequency physical activity groups. Males had higher fat‐free mass than females. The means of fat‐free mass and BMI of sedentary females were higher than those of the more active females with higher frequency of physical activity. In males but not in females, low frequency (less than three sessions per week) of routine PA was associated with lower body weight and body fat compared with sedentary participants. |

| Musaiger and Radwan (1995)58 | Emirates | Urban + rural | 18‐30, 19.7 (1.30) | 215 | Female university students | Sociodemographic factors and dietary habits | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Obesity was the highest in females aged 18 y. There was no significant association between obesity and the social factors studied. The prevalence of obesity was higher in nonnationals, those with educated mothers, having no housemaid, and having a family history of obesity. Skipping meals and snacks had no significant association with obesity. |

| Al‐Kilani et al (2012)59 | Oman | Urban + rural | 21.22 (1.37) | 202 | Omani university students (101 males and 101 females) | Sociodemographic factors, physical activity, and nutrition knowledge | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Male students had a higher prevalence of overweight and obesity than female students. Physical inactivity and lack of basic nutritional knowledge about healthy foods and energy‐dense foods were the main factors associated with overweight and obesity among students. |

| Al‐Nakeeb et al (2015)60 | Qatar | Urban + rural | 18‐25, 21.3 (3.80) | 732 | University students (320 males and 412 females) | Sociodemographic factors, dietary habits, physical activity, and screen time | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Increased screen time, sedentary behaviour, unhealthy diet, and low PA were associated with high BMI. |

| Borgan et al (2015)61 | Bahrain | Urban + rural | 30‐69, 45 (10) | 152 | Physicians (50 males and 102 females) | Sociodemographic factors, sleep duration, physical activity, and screen time | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Physicians with high BMI levels (more than 25) were more likely to be male, older, report fewer than six sleep hours nightly, and have a known diagnosis of hypertension or hyperlipidaemia. There were no significant correlations between increased screen time and obesity. |

| Al Riyami et al (2010)62 | Oman | Urban + rural | 60 and older | 2027 | Elderlies (982 males and 1045 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” | Obesity “BMI” | Interview + survey by researcher | Women were more obese than men. |

| Hajat et al (2012)63 | Emirates | Urban + rural | 18 and older, 36.82 (14.30) | 50 138 | Emiratis residing in Abu Dhabi (43% males and 57% females) | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI and WC” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by specialized nurses | The crude obesity rate was higher among women than among men (38% vs 32%), whereas crude overweight (29% vs 36%) and central obesity (52% vs 59%) rates were lower among women. Males aged 20‐29 were the most overweight and obese category. For females, 30‐39 were the most obese and 20‐29 the most overweight. |

| Mabry et al (2012)64 | Oman | Urban + rural | 20 and older, 36.3 (12.5) | 1335 | Omanis (591 males and 744 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” and physical (in)activity “transport inactivity and sitting time” | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + interview | Physical inactivity (transport inactivity in men and sitting time in women) was associated with high BMI. |

| Musaiger et al (2004)65 | Qatar | Urban + rural | 20‐67 | 535 | Arab females | Ideal body image | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Ideal body image was not related to BMI. |

| Al‐Lawati and Jousilahti (2004)66 | Oman | Urban + rural | 20 and older, 25.3 (5.20) and 25.5 (5.65) | 11 486 | Omanis (5197 males and 6289 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Obesity was higher among men than women. Mean BMI increased with increasing age and peaked in the age group 40‐49 in both genders. Obesity was found to be significantly higher among urban compared with rural populations and among southern regions compared with northern regions. |

| Musaiger and Al‐Ansari (1991)67 | Bahrain | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 420 | Participants who attended a women's sports programme | Sociodemographic factors, socio‐economic factors, and dietary habits | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Increased age, low education, unemployment, marriage, and big family size have a positive association with obesity, while ownership of cars, availability of housemaids, family history of obesity, and meal patterns have no significant association. There were no differences in source of nutrition information between obese and non‐obese women. |

| Al‐Mannai et al (1996)68 | Bahrain | Urban + rural | 20‐64, 36.4 (13.85) | 290 | Bahrainis (137 males and 153 females) | Sociodemographic factors and socio‐economic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Females had a significantly higher prevalence of overweight and obesity compared with males. Participants living in urban areas had a greater tendency to be obese than those residing in rural areas. Marriage, ownership of a car, and a large family (more than seven members) were positively associated with obesity. The educational level was not associated with obesity in either males or females. The age of adult females was not found to be associated with obesity, whereas in males, the incidence of obesity was more frequent among those who were 50 y of age and above than among those under 50 y of age. Family monthly income was not associated with the incidence of obesity. |

| Shah et al (2015)69 | Emirates | Urban | 20‐59, 34 (9.80) | 1375 | South Asian male migrants | Sociodemographic factors | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Nationality, increased age, high monthly salary, low education, working as a driver, salesman, or office worker, having a business or working as shopkeeper or tailor, type of current accommodation, urban residence in their country of origin, being married, longer duration of residency in the Emirates, and being hypertensive were the factors significantly associated with being overweight or obese. |

| Carter et al (2003)70 | Emirates | Urban | 19‐27, 22 | 175 | University medical students (30% males and 70% females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Males were more likely to be overweight or obese than females. |

| Al‐Riyami and Afifi (2003)71 | Oman | Urban + rural | 20 and older, 38.37 (16.65) | 3506 | Omani males | Smoking | Obesity “BMI and WHR” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Current smokers had low BMI compared with nonsmokers and ex‐smokers. Current light smokers had low BMI compared with ex‐smokers. No association of central obesity to smoking status was found. |

| Carter et al (2004)72 | Emirates | Urban | 20 and older | 535 | Females citizens of Al Ain | Sociodemographic factors “gender and education” | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by trained staff | Obesity was associated with increased age and low education for women. Postmenopausal women had lower physical activity and higher rates of obesity than premenopausal women. |

| Rehmani et al (2013)73 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 14 and older | 1339 | Adults living in National Guard housing in the eastern region (769 males and 570 females) | Sociodemographic factors “age, gender, and education” | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements and blood samples by trained staff | Men were significantly more overweight or obese than women. Overweight or obesity increased with age and decreased among participants aged 55 y or older. Higher overweight and obesity levels were related to lower education. |

| Khalid et al (1997)74 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 15‐60 highlanders 35.2 (16.5) and lowlanders 34.8 (15.7) | 498 highlanders (261) and lowlanders (237) | Arab and Saudi national males in Alraish, Alsoda, and Alsoga. | Sociodemographic factors “age” and area | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Anthropometric measurements by researcher | Lowlanders were significantly heavier and taller than highlanders. However, there was no significant difference in BMI level between highlanders and lowlanders. In both highlanders and lowlanders, BMI increased gradually with increased age until the age of 50 y and decreased afterward. |

| Khalid and Ali (1994)75 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | Highlanders 17‐72 and lowlanders 17‐76 | 919 highlanders (451) and lowlanders (468) | Saudi citizens in Alraish and Alsoda highlanders (238 males and 213 females) and lowlanders (189 males and 279 females) | Sociodemographic factors “age and gender” and area | Overweight and obesity “BMI” | Anthropometric measurements by researcher | The highlanders (55.7%) were more overweight or obese than lowlanders (42.9%). Among highlanders only, women were significantly more overweight or obese than men. Both highlanders and lowlanders had higher prevalence of overweight or obesity after the age of 39 y. |

| Binhemd et al (1991)76 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 18‐74 | 1072 | Patients who attended a primary health care centre of King Fahd Hospital of the University, Al‐Khobar (477 males and 595 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender and age” | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by trained staff | Women had a higher obesity rate than men (31.26% vs 16.5%). Obesity was not significantly associated with age. |

| Al‐Awadi and Amine (1989)77 | Kuwait | ‐ | ‐ | 2999 | Females living in Kuwait | Sociodemographic factors | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by trained staff | The prevalence of obesity increased gradually with age, low education, low level of husbands' education, low income, nonworking females, increased family size, and large number of children. However, the prevalence of overweight increased with decreased age, high education, high level of husbands' education, high income, females with a technical profession, decreased family size, and low number of children. |

| Kordy and El‐Gamal (1995)78 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 16 and older | 1037 | Saudi citizens in Queza district, Jeddah (611 males and 426 females) | Sociodemographic factors “age and gender” | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by trained staff | BMI significantly increased with age. BMI was significantly higher in females compared with males. |

| Amine and Samy (1996)79 | Emirates | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 566 | Female university students | Sociodemographic factors, snack intake, physical activity, and napping | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by trained staff | Obesity increased with increased age, obesity during childhood, the presence of an obese parent or both, and high food intake between meals and in particular fast foods. Low levels of physical activity and long afternoon napping were related to obesity. |

| Musaiger and Al‐Mannai (2013)80 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 19‐25 | 228 | Kuwaiti university female students | Media | Obesity “BMI” | Self‐administered survey | Females with obesity were two to three times more likely to be influenced by mass media to undergo dieting to lose weight than those who were not obese. Differences were statistically significant for reading women's magazines and using the internet; however, they were not significant for watching television. |

In the “Main Findings” column, physical (in)activity results are in bold font, dietary habits results are in italic font, sociodemographic results are in regular font, and miscellaneous results are in italic bold font.

Table 2.

Descriptive summary of correlate studies of physical activity

| Author (Year) | Country | Area | Age, range in years and/or mean (SD) | Sample Size | Participants | Correlate Measure | Outcome Measure | By What Measure is the Correlate Evaluated | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sayegh et al (2016)14 | Qatar | ‐ | 18‐64, 37.4 (11.7) | 549 | Qatari females | Sociodemographic factors “age” | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | Results showed that middle‐aged adult females (45‐64 y) were more active, with a daily average of more than 7000 steps, compared with less than 5000 steps per day “sedentary” and 5000‐7499 steps per day “low active” among age groups 18‐24 y and 25‐44 y, respectively. |

| Al‐Nozha et al (2007)16 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 30‐70, 46.3 (11.50) | 17 395 | Saudis (8297 males and 9098 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity “inactivity” | National Epidemiological Health Survey by researcher | There were significantly more inactive females (98.1%) than males (93.9%). Inactivity prevalence increased with increasing age category, especially in males, and decreased with increasing education levels. Inactivity was the highest in the central region and the lowest in the southern region of Saudi Arabia. |

| AlAteeq and AlArawi (2014)18 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 39.2 (8.91) | 322 | Clinicians (127 males and 195 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” and dietary habits | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | There was no significant relation between age and physical activity level. Higher levels of physical activity were associated with better dietary habits. Females had higher physical activity levels than males. Nurses had higher physical activity levels than other clinicians. |

| Almajwal (2015)23 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 362 | Non‐Saudi female nurses | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | Being married, working shift duty, and higher education level were predictors of low physical activity. |

| Khalaf et al (2013)25 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 20.4 (1.50) | 663 | Female university students | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | Low maternal level of education, being married, and living far from parks were related to low physical activity. |

| Samara et al (2015)26 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 18‐22, 20 (0.70) | 94 | Female university students | Sociodemographic factors “gender,” internal factors, external factors, and obesity “BMI” | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | High sedentary behaviour was significantly associated with high BMI. Low self‐efficacy was associated with low physical activity. Low physical activity was associated with lack of facilities and lack of encouragement. |

| Al‐Otaibi (2013)28 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 20‐56 | 242 | Saudis (118 males and 124 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | More males than females were physically active. More males than females were already physically active for more than 6 mo (ie, in the maintenance phase). Females had more external barriers to and less self‐efficacy for physical activity than males. |

| Amin et al (2011)81 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐64, 32.7 (9.80) | 2176 | Saudis (1209 males and 967 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity | Self‐administrated survey | Being female, being older, living in an urban residence, having a higher educational, and occupational status were related to less physical activity. Low PA was associated with societal restrictions and traditions, especially among women and older age groups. Hot weather, lack of facilities, and time were the main associated barriers to low physical activity. |

| Al‐Rafaee and Al‐Hazzaa (2001)82 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 19 and older | 1333 | Saudi males | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Increased age was associated with inactivity; the middle age group was the least active. Physical activity was lower among those who were married, worked in the private sector, worked two shifts, were less well educated, or who had only 1 d off in the week. |

| Khalaf et al (2015)83 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 20.4 (1.50) | 663 | Female university students | Ideal body image | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | There was positive association between high physical activity levels and the desire to be thinner. |

| Al Dokhi and Habib (2013)34 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐72, 36.91 (15.22) | 411 | Saudis (300 males and 111 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | The prevalence of low physical activity was higher in females compared with males. |

| Awadalla et al (2014)84 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 17‐25, 20.1 (1.40) | 1257 | University students (426 males and 831 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Females were less likely to engage in vigorous physical activity than males. Females performed walking activities more frequently than males. Males had more inactive leisure time than females. Non‐membership in sports clubs was related to a greater risk of physical inactivity. Among students at health colleges, colleges of medicine, pharmacy, dentistry, nursing, and applied medical science, students at the college of medicine were more likely to be physically inactive, while students of dentistry were the least likely to be physically inactive. Increased age, higher study level, high parental education/job status, and family income were no significant predictors of physical inactivity. |

| Albawardi et al (2016)40 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 18‐58 | 420 | Saudi females working in office jobs | Sociodemographic and psychosocial factors | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey + height and weight were measured | Females who work seven or more hours per day and do not have children and work in the private sector were less physically active. Social support and general self‐efficacy were not associated with the level of physical activity. Health reasons and maintaining weight were the most important factors associated with high PA. |

| Albawardi et al (2017)85 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐60 | 420 | Saudi females working in office jobs | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity “sitting time” | Self‐administered survey | Workday sitting time was related to level of education (increase by 55 min as education level increased), number of children (sitting decreased by approximately 37 min with each additional child), and working in the private sector (sitting time increased by nearly 80 min per day on work days) compared with the public sector. Nonwork day sitting time was related to number of children (sitting decreased by 27 min with each additional child), marital status (being single compared with married increased sitting time by 73 min per day), and living in a small home compared with a medium home (sitting time reduced by 81 min per day). |

| Mandil et al (2016)86 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 24‐65, 33.11 (9.27) | 360 | Physicians (222 males and 138 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity and sedentary behaviour | Self‐administered survey | Females were more likely to use the internet, than males. Prevalence of physical activity on a daily basis was higher among males (41.6%) than females (16%). |

| Allafi and Waslien (2014)45 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 18‐59, 26 (7.90) | 1370 | Kuwaiti males and females | Sociodemographic factors “gender and age” | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | Increasing age was related to reported inactive behaviour patterns. Women (especially overweight women) felt greater discomfort when exercising around others and disliked exercising more than men. |

| Al Zenki et al (2012)46 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 20‐86, M 39.1 (0.90) and F 40.9 (0.70) | 1830 | Kuwaitis (459 males and 533 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | More males (4.7% ± 1.2%) reported their activity levels as being “very active” than did females (1.3% ± 0.6%). |

| Al‐Isa (2011)48 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 787 | Kuwaiti university students (378 males and 409 females) | Sociodemographic factors, dental and health check‐up, not desiring a higher degree, having no preferred countries for visiting, and obesity “BMI” | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Being female, married, not remembering the last dental and health check‐up, not desiring a higher degree, having no preferred countries for visiting, and obesity were associated with low physical activity. |

| Musaiger et al (2014)51 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 19‐26, 21 (3) | 530 | University students (203 males and 327 females) | Sociodemographic factors and external factors | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | Men perceived far fewer barriers to physical activity (eg, time and climate) than did females. |

| Al‐Asi (2003)53 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 3282 | Kuwait oil company employees (2804 males and 478 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Field workers had a higher level of inactivity outside working hours (65%) than did office workers (56%). |

| Musaiger et al (2015)87 | Bahrain | Urban + rural | 20.1 (2.00) | 642 | University students (90 males and 552 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | Males (41.6%) were more physically active than females (16%). |

| Al‐Nakeeb et al (2015)60 | Qatar | Urban + rural | 18‐25, 21.3 (3.80) | 732 | University students (320 males and 412 females) | Sociodemographic factors and obesity “BMI” | Physical activity | Self‐administrated survey | The percentage of inactive Qatari students is higher compared with non‐Qatari students. Increased sedentary behaviour and high BMI were associated with low PA. |

| Borgan et al (2015)61 | Bahrain | Urban + rural | 30‐69, 45 (10) | 152 | Physicians (50 males and 102 females) | Screen time | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | There were no significant correlations between increased screen time and lack of physical activity. |

| Al Riyami et al (2010)62 | Oman | Urban + rural | 60 and older | 2027 | Elderlies (982 males and 1045 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity | Interview + survey by researcher | Active respondent men were more physically active than women. |

| Mabry et al (2012)64 | Oman | Urban + rural | 20 and older, 36.3 (12.5) | 1335 | Omanis (591 males and 744 females) | Sociodemographic factors and dietary habits smoking | Physical (in)activity “leisure inactivity, inactivity at work, transport inactivity, and sitting time” | Self‐administered survey | Transport inactivity increased with increased age among men. Leisure inactivity in men increased with low levels of education, unemployment, and being married. Leisure inactivity in women increased with unemployment and low FV intake. Women aged 40 y or more had higher inactivity levels at work compared with younger ones. Male smokers aged 30‐39 y had higher mean sitting time than their nonsmoking counterparts. Women aged 20 to 29, unemployed women, and men with high educational level had higher mean levels of sitting time. |

| Mabry et al (2017)88 | Oman | Urban | 18 and older | 2977 | Omani (1490 males and 1487 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | The prevalence of physical activity was higher in men compared with women and in younger participants compared with older ones. Physical activity varied significantly by region of residence, with the highest rate in South Batinah and the lowest in Dhofar and Al Wusta. Unmarried men aged 30‐39 y were twice as likely to be physically active and unmarried women aged 40+ y were half as likely to be active as their married counterparts. Unemployed young women (18‐29 y) were less active than employed women. Higher education was significantly associated with leisure physical activity for men (30 y or more) and women (40 y or more). |

| Mabry et al (2016)89 | Oman | Urban | 18 and older | 2977 | Omani adults (1490 males and 1487 females) | Sociodemographic factors + physical activity | Physical activity “sitting time” | Self‐administered survey | The prevalence of prolonged sitting time (7 h/d or more) was higher in older participants (40 y or more) compared with younger ones (less than 40 y) for both genders. Those who were older (40 y or more), married, less well educated, unemployed, and not physically active had higher mean sitting times than their counterparts. |

| Carter et al (2003)70 | Emirates | Urban | 19‐27, 22 | 175 | Medical students (30% males and 70% females) | External and internal factors | Physical activity | Self‐administrated survey | Low physical activity was associated with lack of time and motivation. |

| Rehmani et al (2013)73 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 14 and older | 1339 | Adults living in National Guard housing in the eastern region (769 males and 570 females) | Sociodemographic factors | Physical activity | Self‐administered survey | Men were more physically active than women. Those who were between 25 and 34 y were the most physically active. Participants with more family members were physically less active. |

Table 3.

Descriptive summary of correlate studies of dietary habits

| Author (Year) | Country | Area | Age, range in years and mean (SD) | Sample Size | Participants | Correlate Measure | Outcome Measure | By What Measure is the Determinant Evaluated | Main Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| El Hamid (2011)90 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 18‐21 | 205 | Female university students | Knowledge and behaviour | Dietary habits “FV consumption” | Self‐administered survey | Students of the nutrition department consumed more vegetables than students from nonnutrition departments. Self‐efficacy and benefits were the most important factors associated with FV consumption, while the department type had no association. |

| AlAteeq and AlArawi (2014)18 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 39.2 (8.91) | 322 | Clinicians (127 males and 195 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” and physical activity | Dietary habits | Self‐administered survey | Higher levels of physical activity were associated with better dietary habits. Better dietary habits increased with increased age and work experience. Females had better dietary habits than males. Physicians and nurses had better dietary habits than pharmacists. |

| Almajwal (2016)24 | Saudi Arabia | Urban | 18 and older | 395 | Non‐Saudi female nurses | Stress and work shift duty | Dietary habits | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Results indicated that nurses with high stress and with undergraduate diplomas had less healthy eating behaviours: restrained eating (the tendency to restrict food intake in order to control body weight), emotional eating (the tendency to cope with negative emotions such as anxiety or irritability), and external eating (the extent to which external cues of food trigger eating episodes, such as the reinforcing value of the sight and smell of attractive food). Nurses working night shift duty had more restrained eating and external eating than those working the day shift. Most of the nurses working night shift duty ate more fast food and snacks and fewer vegetables than nurses who do not work on night shifts. |

| Al‐Gelban (2008)91 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 456 | Saudi male college students | Sociodemographic factors | Dietary habits | Self‐administered survey | There was no relationship between students' parental education and dietary habits. |

| El Hamid (2014)27 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18‐28, 20.78 (1.76) | 400 | Female university students | Sociodemographic factors | Home breakfast skipping | Self‐administered survey | Unhealthy habits (overconsumption of junk foods and soft drinks, poor dairy intake, and sedentary lifestyle) were higher among home breakfast skippers. Unhealthy dietary habits, father's education being lower than university level, and father's unemployment status were related to their daughters' skipping breakfast. In addition, skipping breakfast is related to higher intake of energy‐dense food. |

| Al‐Otaibi (2013)29 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 21.74 (1.55) | 960 | Female university students | Fruit and vegetable consumption | Psychosocial factors | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Students with better dietary knowledge more often consumed five or more servings per day than others with low dietary knowledge. Students with high self‐efficacy consumed more fruits and vegetables than students with low self‐efficacy. Perceived barriers and knowledge were not related to recommended daily fruit and vegetable intake. |

| Khalaf et al (2014)30 | Saudi Arabia | Urban + rural | 18 and older, 20.4 (1.50) | 663 | Female university students | Sociodemographic factors | Dietary habits | Self‐administered survey | Moderate activity level and low household monthly income of 3000 SAR or less were related to breakfast skipping. The intake of vegetables was lower only if the mother works, when siblings with obesity are present, with an increased intake if four siblings or more are obese and with high household income. There were negative associations between the intake of fruits and high number of sisters. On the other hand, the presence of obese siblings as well as high activity levels increased the students' intake of fruits. The age of the participants and their residency's proximity to supermarkets were negatively associated with the milk/dairy products intake. The intake of sugar‐sweetened drinks was significantly associated with the participants' BMI. Further, fast food consumption was negatively associated with the students' age, low activity level, and number of cars in the house. There was a positive correlation between the intake of French fries and potato chips, BMI levels, and the presence of one obese parent. The consumption of sweets/chocolate decreased significantly with increased BMI and if only the mother worked, and it increased with increased proximity to malls and higher educational level of the father. The energy drink intake was a correlate of the mother's higher educational level and lower household income. |

| Musaiger et al (2014)92 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 19‐65 | 499 | Arabs (252 males and 247 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” and knowledge | Fast food intake | Self‐administered survey | Fast food frequency intake per week was higher among men than women. Men were more likely to consume large‐size French fries (40.9% vs 34.0%) and soft drinks (37.3% vs 30.8%) than women. Men tend to eat more “double” burgers (52%) than women (29.9%). |

| Al‐Kandari (2006)54 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 21‐77 | 424 | Kuwaitis (212 males and 212 females) | Smoking | Dietary habits | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | No association was found regarding number of snacks eaten between meals daily and smoking habits. |

| Musaiger et al (2015)87 | Bahrain | Urban + rural | 20.1 (2.00) | 642 | University students (90 males and 552 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” | Dietary habits | Self‐administered survey | Females consumed more afternoon snacks than males (respectively, 35% and 19%). Males (25.6%) had higher consumption of fast food than females (22.5%). Males (50%) had higher fruits intake than females (43.3%). Males (41%) consumed significantly more carbonated beverages than females (19.7%). |

| Al Riyami et al (2010)62 | Oman | Urban + rural | 60 and older | 2027 | Elderlies (982 males and 1045 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender” and knowledge | Dietary habits | Interview + survey by researcher | Women had higher nutritional knowledge than men. Women consumed less milk and fewer milk products than men (14.1% vs 18.8%). The consumption of fish/meat/chicken, cereals, vegetables, or fruits was not statistically different between genders. |

| Mabry et al (2012)64 | Oman | Urban + rural | 20 and older, 36.3 (12.5) | 1335 | Omanis (591 males and 744 females) | Physical (in)activity “leisure inactivity” | Dietary habits “FV intake” | Self‐administered survey | Leisure inactivity in women increased with less FV intake. |

| Musaiger and Abuirmeileh (1998)93 | Emirates | Urban + rural | 20 and older | 2212 | Emirati nationals (1122 males and 1090 females) | Sociodemographic factors “gender and age” | Dietary habits | Self‐administered survey | Men and older participants consumed food more often per day than did women and younger participants, respectively. Elderly people were more likely to consume traditional foods such as fish and laban (diluted yoghurt) than young people. Eggs, cheese, and chicken were found to be consumed significantly less often by older men than young men. Women consumed chicken, vegetables, bread, tea with milk, eggs, and cheese more frequently than men. |

| Al‐Thani et al (2017)94 | Qatar | Urban + rural | 18 and older | 3723 | Qatari and non‐Qatari households | Sociodemographic factors | Dietary habits | Self‐administered survey | Findings showed that the Qatari households purchased nearly 1.5 times more food in grams per capita per day (2118 g/capita/d) compared with the non‐Qatari households (1373 g/capita/d); however, the percentages of food groups in the basket were similar for both groups. Average daily energy (kcal) purchased per capita was almost double among Qatari household (4275 kcal) vs non‐Qatari household (2424 kcal). |

| Zaghloul et al (2012)95 | Kuwait | Urban + rural | 18 and older 38.9 (12.2) | 9350 | Attendees at the Kuwait Medical Council and Public Authority for Social Security facilities (4462 males and 4888 females) | Age, smoking, and physical inactivity | Fruit and vegetable consumption | Self‐administered survey + anthropometric measurements by researcher | Daily fruit and vegetable intake increased with age and BMI but decreased with smoking and physical inactivity. |

Table 4.

Descriptive summary of eligible intervention studies

| Author (Year) | Country | Age, range in years and mean (SD) | Sample Size | Participants | Study Design | Intervention Description | The Timing of the Measurements | Outcome Measurement | Main Findings | Limitations in Articles | Recommendations in Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al‐Sarraj et al (2009)96 | Emirates | 18‐50 | 56 after dropout 39 (14 males and 25 female) | Emiratis with metabolic syndrome | Randomized trial comparing two diets | Carbohydrate restriction diet vs carbohydrate restriction diet followed by the conventional low‐fat diet (3 mo) | At baseline, week 6, and week 12 | Fasting plasma lipids, 24‐h dietary recalls, body composition, anthropometric, blood pressure, glucose, insulin, and plasma markers of inflammation | After 6 wk, reduced body weight (−13%), waist circumference (−4.5%), and body fat (−10.6%) were shown. After 12 wk, positive changes continued for all participants following the diet. However, body weight was lower in the carbohydrate restriction diet group than in the carbohydrate restriction diet followed by the conventional low‐fat diet group. | ‐ | ‐ |

| Yar (2008)97 | Saudi Arabia | 18‐25 | 106 | Saudi male university students in medicine and allied medical sciences | Posttest study | Experiment in physiology course (2 wk, two sessions, 2 h per session) | At the end of the second session | Motivation to increase physical activity, increase healthy eating habits, and increase knowledge about obesity | 74% of students were motivated to engage in more physical activity, 63% of students to adopt healthier eating habits, and 67% of students to enhance their knowledge about obesity. Furthermore, students were motivated to actively engage in the measurement of their BMI. | It is hard to evaluate if intention (reported change in thinking) about the modification of lifestyle will translate into a change in behaviour of the participating students. | |

| Sadiya et al (2016)98 | Emirates | 18‐50 | 45 | Emirati females with obesity or with obesity and type 2 diabetes | Pretest‐posttest study | LIFE‐8: dietary intervention, physical activity intervention, and behavioural therapy (eight sessions of education and counselling, five in groups, three or more individual sessions) | At baseline, month 3 and follow‐up at month 12 | Body weight, fat mass, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting blood glucose, haemoglobin A1c, and nutritional knowledge | The intervention resulted in a reduction of 5.0% in body weight (4.8 ± 2.8 kg; 95% CI, 3.7‐5.8), fat mass (−7.8%, P < 0.01), and waist circumference (Δ = 4 ± 4 cm, P < 0.01) in the participants who completed the intervention (n = 28). Increase in nutritional knowledge (less than 0.01) and overall evaluation of the programme (9/10) was favourable. On 1‐y follow‐up, the participants could sustain weight loss (−4.0%). | Small sample size. There is no control intervention programme and the sample included only women. | Additional evidence from a randomized, controlled trial is essential to evaluate the short‐term and long‐term clinical advantages and cost‐effectiveness of the LIFE‐8 programme in this region. Since it is an ongoing programme, further studies with a larger sample size could provide insight into the generalizability of the results. |

| Midhet and Sharaf (2011)99 | Saudi Arabia | 20 and older | Baseline 1254 (70.7% males, 29.4% female) and follow‐up 1011 (65.3% males, 34.7% female) | Primary health care centres' visitors | Pretest‐posttest study with different samples at pretest and posttest | Health education intervention (10 mo) | At baseline and at month 10 | Knowledge level, unhealthy dietary habits, regular exercise, and smoking | The intervention resulted in a decrease in the consumption of kabsa, bakery items, and dates and an increase in fish and fresh vegetables. Participants were less likely to smoke and more likely to do regular exercise. No significant impact of the intervention on the female population with regard to exercise. | Uncontrolled pretest‐posttest, with different samples at pretest and posttest. | Promoting healthy lifestyles and informing the public on the hazards of leading a sedentary life, and engaging in unhealthy practices is the only way to control and contain the unprecedented increase in lifestyle related diseases in Saudi Arabia. |

| Albassam et al (2007)100 | Saudi Arabia | 18‐40 | 212 | Saudi females attending diet clinics | Pretest‐posttest study | Weight management programmes: four different diet programmes and one physiotherapy exercise programme | At baseline, and at the end of each programme (varies from 6 wk up to 10 mo) | Weight loss (%) | Moderate hypocaloric plan diet had, compared with the other four groups, the lowest per cent weight loss (7.8%) and the least side effects. Both groups under very low‐calorie diets and protein diets had the highest per cent weight reduction (13.2% and 12.3%) with the highest number of side effects. | ‐ | Use of the primary approach for achieving weight loss through therapeutic life style change is recommended. |

| Alghamdi (2017)101 | Saudi Arabia | 20 and older | 140 (70 males, 70 female) | Arab participants with obesity who were otherwise healthy | Randomized controlled trial | Intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) programme; diet, exercise, and behavioural techniques using goal setting, self‐monitoring, and stimulus control (eight visits) vs active comparator programme (received only an initial health education session) | At baseline and follow‐up at month 3 | Weight loss (%) | Participants in ILI programme more often achieved a 5% weight reduction and showed significantly greater weight loss at 3 mo than the active comparator group. | High attrition rates, 36% of the participants dropped out of this study. No follow‐up for a longer period. | Similar programmes are needed to be implemented in the region. Further research is essential to evaluate the long‐term effectiveness of ILI among obese population and to identify effective methods for long‐term weight‐loss maintenance. |

| Armitage et al (2017)102 | Kuwait | 30.11(11.2) | 216 (61 males, 127 female, 28 unknown) | Participants enrolled in a weight‐loss programme | Randomized controlled trial | Weight‐loss intervention programme using volitional help sheet to form implementation intentions vs the control group (use the volitional help sheet to think about critical situations and appropriate responses) | At baseline and at month 6 | Weight loss (%) | At 6 mo, the intervention group lost significantly more weight (6.15 kg; −6.58% initial body weight) than those in the control group (3.66 kg; −4.04% initial body weight). | No follow‐up for a longer period, small sample size; all subjects were in treatment, and they were highly motivated to lose weight, no published protocol or data analysis plan prior to data collection, bias due to simple randomization method. | ‐ |

3. RESULTS

First, the results of the 84 eligible correlate studies14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95 are described, followed by the data on the seven intervention studies.96, 97, 98, 99, 100, 101, 102

3.1. Correlate studies

All correlate studies were cross‐sectional,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95 except for one longitudinal study.14 Half of the studies were performed in Saudi Arabia,15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 73, 74, 75, 76, 78, 81, 82, 83, 84, 85, 86, 90, 91 and a large number were performed in Kuwait.45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 77, 80, 92, 95 Approximately 30% of studies involved university students. Most correlate studies were conducted in both urban and rural areas; a few studies were conducted on urban populations only, while no study was based on rural populations only. More than 60 studies included both genders, while 25 included women only and eight included men only.

In order to present the findings of the correlate studies in a structured way, we grouped them into three categories (1) studies on correlates of overweight/obesity, (2) studies on behavioural correlates of PA and sedentary behaviour, and (3) studies on behavioural correlates of dietary behaviours.

3.1.1. Correlates of overweight/obesity

There were 69 studies of correlates of overweight/obesity (see Table 1 for details). Most studies investigated only sociodemographic factors as correlates of overweight/obesity, while a substantial number looked at dietary behaviours, PA, and sedentary behaviour as correlates of overweight/obesity. Some studies associated sleep duration, sleep disturbance, media, and body image with overweight/obesity. The results of Table 1 are discussed under the following headings: (a) PA and sedentary behaviour, (b) dietary behaviours (consumption behaviours), (c) sociodemographic factors (such as gender, age, education, and marital status), and (d) miscellaneous (such as sleeping behaviour, smoking, and family history of obesity). Many studies addressed correlates of more categories (eg, PA as well as sociodemographic factors).

PA and sedentary behaviour

The results indicated that people who were physically active showed lower levels of BMI and waist circumference (WC) than people who were less physically active.15, 16, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 30, 36, 37, 47, 48, 49, 52, 54, 57, 60, 79 Two studies found no significant association between PA and obesity.14, 44 Personal barriers to PA, such as lack of interests, skills, and motivation, were experienced more by men with obesity than by others.51 Women with obesity felt more embarrassed when exercising outdoors than women who were non‐obese.51 Many studies showed that increased sedentary and physical inactivity behaviours were associated with high BMI.19, 22, 23, 26, 36, 45, 48, 49, 57, 59, 60, 64 Transport inactivity among men and sitting time among women were associated with high BMI.64 With the exception of one study,61 the findings showed quite consistently that all types of inactivity were correlates of overweight/obesity.

Dietary behaviour

The findings suggested that there was an association between unhealthy dietary habits and overweight/obesity. A positive correlation was observed between caloric intake and BMI levels.19, 22, 23 Low consumption of fruit and vegetable (FV), fibre, grains, and beans; high consumption of fat; high fast food intake; high soft drinks consumption; eating with friends; or eating out were the main eating behaviours that were associated with obesity.20, 29, 30, 36, 37, 54 However, in one study, vegetable consumption was higher among participants with obesity49 compared with their normal‐weight counterparts. The associations between skipping meals and obesity were not consistent.27, 58, 67 Findings related to frequent unhealthy snacking and obesity were inconsistent as well.31, 58, 79 The tradition of food hospitality and other behaviours related to eating, such as eating due to emotional states of stress, anger, and boredom, were correlated with female obesity.22 Lack of basic nutritional knowledge about healthy food and energy‐dense food was one of the main factors associated with overweight/obesity.59 People who ate breakfast at home had significantly higher BMI levels compared with those who skipped breakfast at home.27, 49

Sociodemographic factors

Fifty‐two studies investigated the association between sociodemographic factors and overweight/obesity among adults. Most studies showed that increased age was significantly associated with overweight/obesity but that weight seemed to drop again after the age of 50 or 60.50, 68, 72, 74, 75 While some studies showed that women had a significantly higher prevalence of overweight/obesity compared with men,21, 32, 35, 52, 55, 62, 68, 75, 76, 78 others showed the opposite.19, 29, 36, 39, 41, 42, 44, 53, 59, 70, 73 Most studies showed that obesity was higher among married adults.20, 21, 30, 40, 50, 56, 67, 68, 69 While some studies revealed that low income was associated with a high prevalence of obesity,21, 40, 69, 77 others stated the opposite.36, 48 The majority of studies indicated that low educational level was associated with a high prevalence of obesity15, 21, 30, 33, 38, 56, 67, 69, 71, 72, 73, 77; only one study contradicted this finding.40 Obesity was higher among people without jobs, particularly housewives,21, 38, 67, 77 and rates were higher among people living in urban areas compared with people living in rural areas,17, 32, 56, 66, 68, 71 with the exception of two studies.32, 38

Miscellaneous

The remaining studies on overweight/obesity correlates addressed miscellaneous factors. Obesity was higher among those who had parents or immediate relatives with obesity or lived with their parents.20, 30, 47, 48, 52, 58, 79 The results of several studies also suggest that living together with more relatives is associated with higher weight.54, 68, 77 The relation between smoking status and BMI/obesity was inconsistent between studies.15, 71, 74 Recent studies have also investigated sleep in relation to weight/obesity in the Gulf States. Obesity was significantly associated with sleep disturbances43 and short sleep duration.41, 42, 61

3.1.2. Behavioural correlates of PA and sedentary behaviour

There were 29 studies on correlates of PA; the majority involved sociodemographic factors (see Table 2). Most studies on PA showed that women had lower PA levels than men.16, 28, 34, 45, 46, 48, 73, 81, 84, 89 Those who were older (40 y or more), married, less educated, unemployed, and not physically active had longer mean sitting times than younger ones.88, 89 However, one study showed that age was not a significant correlate of physical inactivity.84 Another study showed that women aged 45 to 64 years were more active than younger women.14 While some studies indicated that higher educational and occupational status were associated with lower PA in the Gulf States,25, 81 other studies showed the opposite.82, 84 Residing close to parks was related to higher levels of PA.25 Furthermore, being married,27, 50 working in the private sector, working two shifts, or having only 1 day off during the week were associated with low PA.14, 23, 82, 85 Participants with more family members were physically less active.73 Social support and general self‐efficacy were not significantly associated with the level of PA.14

3.1.3. Behavioural correlates of dietary behaviours

The 15 studies on correlates of dietary behaviours were mostly on sociodemographic factors; for details, see Table 3. The results are discussed based on the kind of dietary behaviour, ie, (a) FV intake, (b) fast food snacks and sugar intake, and (c) meal patterns and skipping meals.

FV intake

Studies in general showed a low consumption of FV (less than five servings a day) in the Gulf region.29, 31, 64, 90, 93, 95 Women consumed vegetables more frequently than men.68, 95 Men had a higher fruit intake than women.87 The relation between level of nutritional knowledge and FV consumption was inconsistent.29, 90 High self‐efficacy was associated with high FV intake.20, 90 Perceived benefits such as weight maintenance, preventing disease, and feeling better were significant correlates for increased FV consumption.90 Daily FV intake increased with age and BMI but decreased with smoking and physical inactivity.95

Fast food snacks and sugar intake