Abstract

Aims

Pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) is underdiagnosed on biopsy specimens. We evaluated if routine neuroendocrine immunohistochemical (IHC) stains are helpful in the diagnosis of LCNEC on biopsy specimens.

Methods and results

Using the Dutch pathology registry (PALGA), surgically resected LCNEC with matching pre‐operative biopsy specimens were identified and haematoxylin and IHC slides (CD56, chromogranin‐A, synaptophysin) requested. Subsequently, three pathologists assigned (1) the presence or absence of the WHO 2015 criteria and (2) cumulative size of all (biopsy) specimens. For validation, a tissue microarray (TMA) of non‐small‐cell lung cancer (NSCLC) (n = 77) and LCNEC (n = 19) was used. LCNEC was confirmed on the resection specimens in 32 of 48 re‐reviewed cases. In 47% (n = 15 of 32) LCNEC was also confirmed in the paired biopsy specimens. Neuroendocrine morphology was absent in 53% (n = 17 of 32) of paired biopsy specimens, more often when smaller amounts of tissue were available for evaluation [29% < 5 mm (n = 14) versus 67% ≥5 mm (n = 18) P = 0.04]. Combined with current WHO criteria, positive staining for greater than or equal to two of three neuroendocrine IHC markers increased the sensitivity for LCNEC from 47% to 93% on paired biopsy specimens, and further validated using an independent TMA of LCNEC and NSCLC with sensitivity and specificity of 80% and 99%, respectively.

Conclusions

LCNEC is difficult to diagnose because neuroendocrine morphology is frequently absent in biopsy specimens. In NSCLC devoid of obvious morphological squamous or adenocarcinoma features, positive staining in greater than or equal to two of three neuroendocrine IHC stains supports the diagnosis of LCNEC.

Keywords: carcinoma, neuroendocrine (MESH), lung neoplasms (MESH), diagnosis (MESH), biopsy (MESH), sensitivity and specificity (MESH), WHO classification, LCNEC

Introduction

In lung cancer most diagnoses are made on relatively small biopsies and cytology.1 The histological features pointing to diagnosis adenocarcinoma, squamous‐cell carcinoma or LCNEC may be challenging.2 The distinction between adenocarcinoma and squamous‐cell carcinoma in the context of non‐small‐cell lung carcinoma not otherwise specified (NSCLC‐NOS) has been addressed in the World Health Organisation (WHO) classification of lung tumours of 2015 by the introduction of several markers, including mucin, thyroid transcription factor‐1 (TTF1) and P63/P40.3 More recently, the added value of immunohistochemical (IHC) markers in the differential diagnosis of small‐cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) has been described.4

LCNEC is a high‐grade neuroendocrine carcinoma originally described in 1991.5 The diagnostic criteria for LCNEC include observation of abundant mitoses (>10 mitosis/2 mm2), neuroendocrine morphology such as rosettes, trabecular growth pattern or palisading of cells and neuroendocrine differentiation usually identified by IHC markers. Although in recent practice LCNEC has been diagnosed more frequently on biopsy specimens,6 the diagnostic accuracy and precision for a diagnosis of LCNEC on a biopsy specimen is unknown and not well studied.7, 8, 9, 10, 11

As described by national guidelines, one of the first‐line treatment options for non‐squamous NSCLC is cisplatinum‐pemetrexed chemotherapy.12 A patient with metastatic LCNEC disease that is not recognised as such, because neuroendocrine morphology is lacking in a biopsy specimen, may be diagnosed as non‐squamous NSCLC (i.e. P63‐negative, TTF1‐positive or ‐negative) and treated with cisplatinum‐pemetrexed chemotherapy. Recently, a study evaluating outcome of 128 patients with metastatic LCNEC reported an inferior outcome for cisplatinum‐pemetrexed and platinum‐etoposide chemotherapy compared to platinum‐gemcitabine/paclitaxel chemotherapy.13 Therefore, it is clinically relevant to reliably separate LCNEC from NSCLC on biopsy specimens.

The purpose of this study was to establish if the outcome of the current frequently used neuroendocrine IHC stains on biopsy samples may be helpful in the diagnosis of LCNEC. To this end, two independent cohorts of LCNEC and a cohort of NSCLC were examined for the presence of diagnostic criteria for LCNEC by a panel of pathologists as well as the outcome of three IHC stains (CD56, chromogranin A, synaptophysin).

Material and methods

Regulations

The study protocol was approved by the medical ethical committee of the Maastricht University Medical Centre (METC azM/UM 14‐4‐043) and was performed according to the Dutch Federa, Human Tissue and Medical Research: Code of Conduct for Responsible Use (2011) regulations not requiring patient informed consent.

Patient and Tumour Selection

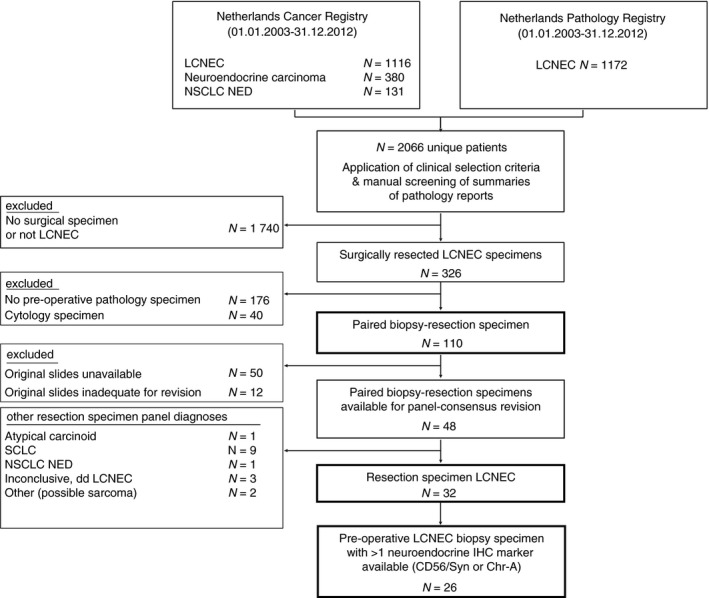

In this retrospective population‐based study all data were retrieved from the Netherlands Cancer Registry and Netherlands Pathology Registry (PALGA, the nationwide registry of pathology in the Netherlands14), as described previously. In short, by screening digital summaries of pathology reports, 994 patients with LCNEC were identified in the combined data sets of patients diagnosed between 1 January 2003 and 31 December 2012. In a total of 326 (33%) LCNEC patients the primary tumour was surgically removed. By screening the patient pathology history, we identified 110 (34%) patients in whom a histopathological biopsy specimen was obtained from the matching anatomical location where the tumour was surgically removed (i.e. a paired pre‐operative biopsy‐resection specimen). From 60 of the 110 cases, haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and IHC stains of both the resection and biopsy specimens were available for panel revision (Figure 1). Subsequently, 12 cases were excluded because the original H&E tumour slide(s) were deemed inadequate by reviewing pathologists.

Figure 1.

Selection of surgical LCNEC specimens with pre‐operative biopsy specimens available for panel review. N, number; LCNEC, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; NSCLC NED, non‐small‐cell lung carcinoma with immunohistochemical neuroendocrine differentiation; SCLC, small‐cell lung carcinoma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; Syn, synaptophysin; Chr‐A, chromogranin‐A.

Panel Consensus Pathology Revision

The retrieved IHC stains included the neuroendocrine markers [chromogranin‐A, synaptophysin and CD56 (NCAM)], TTF1, P63, Ki‐67 and available cytokeratin markers. All IHC markers were stained in routine diagnosis. All cases minimally required an H&E stain and one of three neuroendocrine IHC markers, as described previously. Subsequently, all tumour slides were systematically evaluated by three pathologists (R.v.S., M.d.B. and E.T.) using a multihead microscope. All pathologists were blinded for clinical outcome and for matching biopsy‐resection specimens. Total tissue size of the biopsy specimens was estimated by applying the following categories: ≤2, >2 but ≤5, >5 but ≤10 and >10 mm. The total size of the samples was evaluated guided by the field of view of the microscope objective. In overview magnification (×2.5) the total size should well exceed the field of view (diameter 8 mm) to be larger than 10 mm; if at ×2.5 objective the total size was smaller than the maximum, but covering more than half the field of view, the size was between 5 and 10 mm; smaller samples were evaluated at ×10 objective: if the total sample size was smaller than the field of view (diameter 2 mm) then the total size was less than 2 mm, or it was between 2 and 5 mm.

H&E slides of both resection and biopsy specimens were examined for (i) cell type, presence of cytoplasm and tumour to lymphocyte ratio to assess NSCLC of SCLC features according to the WHO 2015 classification, (ii) the presence of neuroendocrine morphology, (iii) estimated mitotic activity in non‐crushed fields [≤10, 11–30 or >30 mitoses/10 high‐power field (HPF)], (iv) necrosis [none, ‘dot‐like’ (=as occasionally seen in atypical carcinoids) or abundant (= more extensive than ‘dot‐like’)]. If available, the MIB1 (Ki‐67) staining was scored into <25% and >25%.15, 16 In more limited tissue samples (<2 mm2), mitoses were evaluated on all assessable HPFs.4 Either >10 mitoses/2 mm2, abundant tumour necrosis or a Ki‐67 staining of more than 25% of tumour cells was sufficient to score for high‐grade tumour disease.15 Chromogranin‐A and synaptophysin were scored as (+) on observation of focal small cytoplasmic dots in an occasional tumour cell at ×40 microscope. Any membrane staining was sufficient for CD56 (+). For all neuroendocrine markers, observation of staining (×4 or ×2.5 objective) was scored as strongly positive (+++), and between staining as (++). Additionally, p63/p40/TTF1 and cytokeratin stainings were evaluated when these were available. LCNEC diagnoses were established when both neuroendocrine morphology and neuroendocrine staining of at least a single marker was present, as according to the algorithm as described in the WHO classification (2015).

Tissue Microarray for Validation

A TMA cohort was constructed from adenocarcinoma (n = 33), squamous cell carcinoma (n = 29) NSCLC not otherwise specified (n = 15), carcinoid (n = 18), LCNEC (n = 19) and SCLC (n = 3) surgically resected tumours diagnosed at Maastricht University Medical Centre (1998–2015). Three cores, each 2‐mm thick, were sampled into a donor block. Staining for chromogranin‐A (DAK‐A3), synaptophysin (DAK‐SYNAP), CD56 (123C3), TTF1 (SPT24), P63 (DAK‐P63) and KI67 (DAK‐7240) was performed according to routine diagnostic protocols. Expression of IHC markers were evaluated by J.D. and E.T. and scored using H‐score; P‐63 was scored positive when H‐score >200. TMA cores were evaluated for diagnosis by a single pathologist (E.T.), who was blinded for the original diagnosis according to (1) the WHO 2015 criteria and (2) the WHO 2015 with addition of newly proposed LCNEC criteria for limited tissue samples.

Statistics

All analyses were performed using spss (version 22 for Windows, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). To compare categorical data, the χ2 and Fisher's exact test were used. Two‐sided P‐values of <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Paired Resection‐Biopsy Specimen Comparison

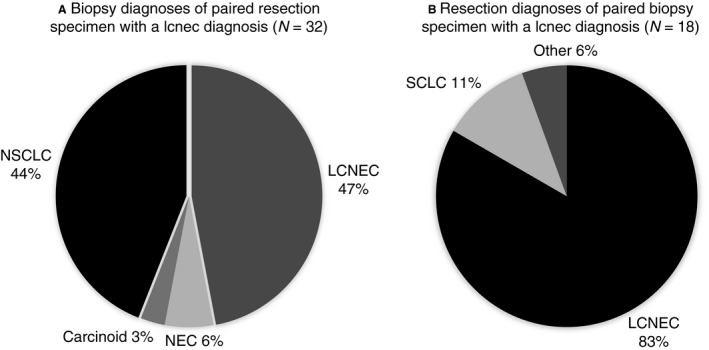

In total, 48 cases of LCNEC were available for panel review. After reviewing all resection specimens, only 32 of 48 cases were revised as LCNEC (Figure 1). In only 47% (15 of 32) of these revised LCNEC cases was the diagnosis of LCNEC also established on the paired biopsy specimens. Other paired biopsy specimen diagnoses (17 of 32) included NSCLC (44%), carcinoid (3%) and inconclusive diagnosis (6%), respectively (Figure 2A). In total, 18 of 48 pre‐operative biopsy specimens were revised as LCNEC; paired revised resection diagnosis was LCNEC in 83%; other diagnoses included SCLC (12%) and a non‐unanimous revised case (overview Figure 2B). An overview of all diagnostic criteria identified in the paired biopsy specimens of revised confirmed surgically resected LCNEC is presented in Table 1 and an exemplar case in Figure 3A,B.

Figure 2.

A, Overview of diagnoses established on paired pre‐operative biopsy specimens of surgically diagnosed LCNEC by panel‐consensus revision (n = 32); samples were taken from identical anatomical regions. B, Overview of diagnoses established on the resection specimens of paired pre‐operative biopsy specimens diagnosed as LCNEC (n = 18). Others included here are cases without a unanimous diagnosis by the classifying pathologists. LCNEC, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; SCLC, small‐cell lung carcinoma; NSCLC, non‐small‐cell lung cancer; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma not otherwise specified.

Table 1.

Results of structured WHO criteria evaluation in biopsy specimen from surgical resection specimen diagnosed as LCNEC

| Resection | Biopsy (1) | Biopsy (2) | Specimen | Grading | Morph. | Neuroendocrine IHC | Other IHC | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel review | Original diagnosis | Type | Size (mm) | Mit. | Nec. | Ki‐67% | High‐grade | Neuro. | CD56 | Syn | Chr‐A | ≥2+ | TTF1 | P63 | |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | NSCLC, AdC NED | Needle | >5–10 | >10 | +/− | >25 | + | + | UA | ++ | − | No | + | UA |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | SCLC | Needle | >10 | >10 | + | UA | + | + | ++ | − | − | No | − | UA |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | LCNEC | Needle | >10 | >30 | + | UA | + | + | + | UA | UA | UA | − | UA |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | LCNEC | EBB/TBB | >2–5 | >30 | + | UA | + | + | +++ | UA | UA | UA | − | − |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | LCNEC | Needle | >10 | >10 | + | UA | + | + | + | ++ | ++ | Yesa | − | − |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | LCNEC | Needle | >10 | >10 | + | UA | + | + | +++ | ++ | − | Yesa | + | UA |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | AC dd LCNEC | Needle | >5–10 | >10 | + | >25 | + | + | ++ | ++ | ++ | Yes | − | UA |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | NSCLC, ADC | Needle | >10 | >10 | + | UA | + | + | − | + | ++ | Yes | UA | UA |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | SCLC dd LCNEC | EBB/TBB | <2 | >10 | − | >25 | + | + | ++ | UA | + | Yes | + | − |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | LCNEC | Large BB | >10 | >30 | + | UA | + | + | ++ | +++ | − | Yes | + | UA |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | NSCLC NED | Needle | >10 | >30 | + | UA | + | + | − | + | ++ | Yes | − | − |

| LCNEC | LCNEC | AC | EBB/TBB | >2–5 | >10 | + | UA | + | + | + | +++ | − | Yes | + | UA |

| SCLC‐LCNEC | LCNEC | SCLC | Needle | >10 | >30 | − | >25 | + | + | +++ | UA | ++ | Yesa | + | UA |

| NSCLC‐LCNEC | LCNEC | SCLC | EBB/TBB | <2 | >30 | − | >25 | + | + | ++ | + | + | Yes | − | UA |

| SqCC‐LCNEC | SqCC‐LCNECb | NSCLC, adenosquamous | Needle | >10 | >10 | + | >25 | + | + | ++/− | − | − | No | + | −/+ |

| LCNECb | AC | AC | EBB/TBB | <2 | <10 | − | <25 | − | + | + | UA | +++ | Yes | − | UA |

| LCNEC | Favor AdC | LCNEC | EBB/TBB | <2 | UA | − | UA | − | − | ++ | ++ | ++ | Yes | + | UA |

| LCNEC | Favor AdC | NSCLC NED | Needle | >10 | >30 | + | >25 | + | − | + | + | − | Yes | + | − |

| LCNEC | NSCLC NOS | LCNEC | Needle | >2–5 | >30 | + | >25 | + | − | − | +++ | ++ | Yes | − | − |

| LCNEC | Favor AdC | NSCLC NED | EBB/TBB | >5–10 | >30 | + | >25 | + | − | − | + | − | No | + | UA |

| LCNEC | Favor AdC | SCLC | EBB/TBB | <2 | UA | − | >25 | + | − | + | UA | UA | UA | + | − |

| LCNEC | Favor AdC | CARCINOID, dd SCLC | EBB/TBB | >2–5 | UA | − | <25 | − | − | + | UA | ++ | Yes | + | − |

| LCNEC | Favor AdC | AC | Needle | >5–10 | <10 | + | UA | − | − | − | ++ | +++ | Yes | + | UA |

| LCNEC | NSCLC NOS | LCNEC | EBB/TBB | <2 | >10 | − | UA | + | − | + | UA | ++ | Yes | − | − |

| LCNEC | NSCLC NOS | SCLC | EBB/TBB | >2–5 | <10 | − | UA | − | − | ++ | − | ++ | Yes | − | UA |

| LCNEC | NSCLC NOS | NSCLC NED | EBB/TBB | >2–5 | >10 | + | UA | + | − | ++ | ++ | − | Yesa | UA | UA |

| LCNEC | NSCLC NOS | LCNEC | Needle | >10 | <10 | + | >25 | + | − | ++ | + | − | Yes | − | UA |

| LCNEC | NSCLC NEM | LCNEC | Needle | >10 | >10 | + | >25 | + | + | − | − | − | No | − | Focal |

| LCNEC | Favor AdC | ADC | EBB/TBB | <2 | >10 | − | UA | + | − | UA | UA | − | UA | + | UA |

| SqCC‐LCNEC | SqCC | SQCC | EBB/TBB | >10 | UA | − | UA | − | SqCC | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA |

| LCNEC | NSCLC versus SCLC | LCNEC | EBB/TBB | <2 | UA | + | − | + | − | +++ | UA | UA | UA | UA | UA |

| LCNEC | NSCLC versus SCLC | LCNEC | Needle | >10 | >30 | + | − | + | − | ++ | + | − | Yes | − | − |

UA, unavailable; IHC, immunohistochemistry; NOS, not otherwise specified; NSCLC NED, NSCLC with neuroendocrine IHC differentiation; AdC, adenocarcinoma; SqCC, squamous cell carcinoma; AC, atypical carcinoid; EBB, endobronchial biopsy; TBB, transbronchial biopsy; Syn, synaptophysin; Chr‐A, chromogranin‐A; Foc, focal; SCLC, small‐cell lung carcinoma; LCNEC, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; dd, differential diagnosis; NEM; neuroendocrine morphology without staining for neuroendocrine markers.

IHC staining is performed only on the biopsy specimen.

Resection sample of LCNEC based on mitosis, but importantly, no abundant necrosis was observed and tumour had well‐differentiated morphology; in Ki‐67 strong heterogeneity was observed within the tumour (<25% and >25%).

Neuroendocrine part is positive for CD56 but negative for P40.

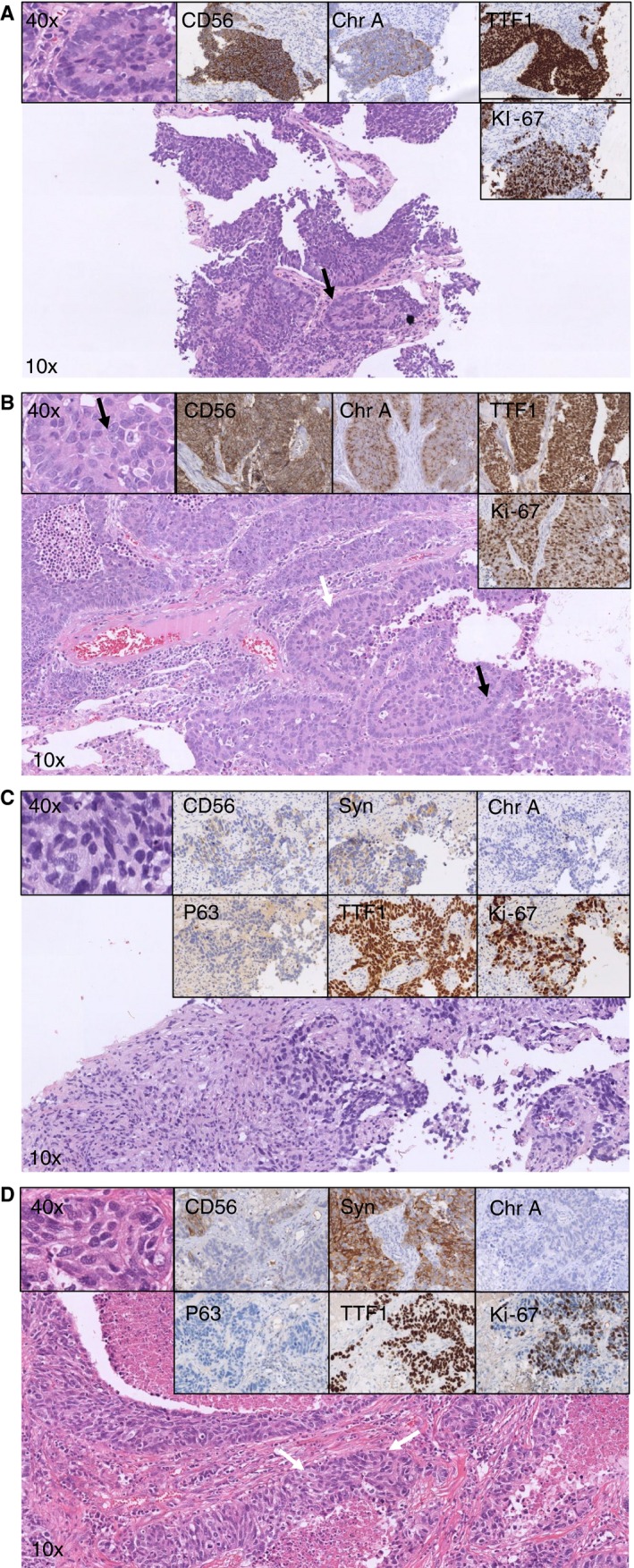

Figure 3.

A–D, Overview of haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining in paired pre‐operative biopsy‐resection specimens’ consensus diagnosed as LCNEC on the resection specimens. LCNEC, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; NSCLC, non‐small‐cell lung carcinoma. Biopsy specimen (A) (matched with resection specimen B): according to the established WHO classification, NSCLCs favouring LCNEC would be diagnosed. Neuroendocrine morphology (palisading, arrow) is observed. The left upper panel shows cells with non‐small‐cell cytological features. CD56 and chromogranin‐A staining confirm neuroendocrine differentiation (upper middle panels), thyroid transcription factor‐1 (TTF1) is positive (upper right), while high‐grade disease is confirmed with the Ki‐67 staining (>25%, lower right panel). Resection specimen (B) (matched with biopsy specimen A): according to the established WHO classification, LCNEC would be diagnosed. Identical to the biopsy specimen, neuroendocrine morphology is present (palisading, white arrow). In the left upper panel non‐small‐cell cytological features can be observed with abundant cytoplasm and nucleoli (arrow). The black arrow highlights a mitosis, while the Ki‐67 (lower right panel) confirms high‐grade disease (>25%). Biopsy specimens (C) (matched with resection specimen D): according to the established WHO classification, NSCLCs favouring adenocarcinoma would be diagnosed. According to the current study, the proposed diagnosis will be LCNEC, confirmed in the resection specimen (D). In the overview, an undifferentiated NSCLC is observed (cytological features, left upper panel). P63 is negative but TTF1 is strongly positive (middle lower panel). High‐grade disease is confirmed with the Ki‐67 (>25%, lower right panel). The neuroendocrine marker CD56 shows modest membranous staining (upper middle left), synaptophysin shows granular staining (upper middle right) while chromogranin‐A is negative (upper right). Resection specimen (D) (matched with biopsy specimen C): according to the established WHO classification, LCNEC would be diagnosed. In the overview, a neuroendocrine morphology is present (white arrows) and cytological features of a non‐small cell with abundant cytoplasm (left upper panel). Immunohistochemical markers show identical patterns to the biopsy specimen (middle lower and upper panels).

Data of non‐LCNEC revised resected cases are presented in Supporting information, Table S1, and mainly included SCLC (n = 9). Paired biopsy specimen diagnoses of these SCLC cases included LCNEC (n = 2), SCLC (n = 1) and NSCLC (n = 5), and one had a differential diagnosis of SCLC versus NSCLC, respectively.

Evaluation of Who Criteria on the Paired Biopsy Specimens

When evaluating the paired biopsy specimens from surgically confirmed LCNEC, the WHO 2015 criteria could only be observed to a variable extent. Overall, ‘neuroendocrine morphology’ was not observed in 50% of biopsy samples. However, in biopsy samples with a cumulative size of >5 mm tumour tissue this morphology was more frequently observed compared to smaller samples [67% versus 29%, respectively (P = 0.04), Table 2]; an exemplar biopsy case is shown in Figure 3C. Comparison of the cumulative biopsy size revealed no significant difference for the presence of mitosis, nucleoli, cytoplasm and necrosis.

Table 2.

Comparison of WHO criteria evaluated in the paired pre‐operative biopsy and resection specimens of LCNEC

| WHO 2015 criteria | Specimen type | P‐valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre‐operative biopsy | Resection | <5 mm versus >5 mm | |||

| Total | <5 mm | ≥5 mm | Total | ||

| Total (n) | 32 | 14 | 18 | 32 | – |

| Mitosis (% scored as in resection specimen) | 72% | 57% | 83% | – | 0.13 |

| ≤10 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| >10 | 23 | 8 | 15 | 31 | |

| Not assessable | 5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | |

| Necrosis (% scored as in resection specimen) | 63% | 50% | 72% | – | 0.28 |

| Large zones | 20 | 5 | 15 | 26 | |

| Dotlike (focal necrosis as in AC) | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | |

| No necrosis | 10 | 9 | 1 | 2 | |

| Not assessable | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Neuroendocrine morphology (% scored as in resection specimen) | 50% | 29% | 67% | – | 0.04b |

| Not present | 9 | 4 | 5 | 0 | |

| Present | 15 | 5 | 10 | 31 | |

| Heterogeneous among pathologists | 3 | 0 | 3 | 1 | |

| Not assessable | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | |

| ≥2/10 large (non‐inconspicuous) nucleoli (% scored as in resection specimen) | 59% | 50% | 67% | – | 0.47 |

| No | 28 | 11 | 17 | 18 | |

| Yes | 3 | 3 | 0 | 13 | |

| Heterogeneous among pathologists | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| Not assessable | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Cytoplasm as in NSCLC (% scored as in resection specimen) | 88% | 93% | 83% | – | 0.61 |

| No | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Yes | 29 | 13 | 16 | 30 | |

| Heterogeneous among pathologists | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Changing within specimen (i.e. yes and no) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Not assessable | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Moulding (% scored as in resection specimen) | 69% | 86% | 55% | – | 0.12 |

| No | 25 | 13 | 12 | 25 | |

| Yes | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Heterogeneous among pathologists | 2 | 0 | 2 | 6 | |

| Not assessable | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

NSCLC, non‐small cell lung carcinoma, AC, atypical carcinoid; mm, millimeters.

Fisher's exact test comparing number of paired and resection specimens identically scored for WHO criteria subcategory.

χ2 test comparing number of paired and resection specimens identically scored for WHO criteria subcategory (i.e. neuroendocrine morphology present in both specimens).

Evaluation of New Diagnostic Criteria for LCNEC on Biopsy Specimens

We then hypothesised that in LCNEC biopsy specimens lacking neuroendocrine morphology, the neuroendocrine marker staining pattern may be of additional diagnostic value. For 26 of 32 confirmed LCNEC cases, two or more neuroendocrine markers were available (Figure 1). When the presence of staining for ≥2 neuroendocrine IHC markers was considered as a surrogate marker for neuroendocrine morphology in the biopsy specimens, then the diagnosis of LCNEC would have increased from 47% (n = 15 of 32) to 81% (n = 26 of 32). When cases were excluded in which fewer than two neuroendocrine markers were available and lacked neuroendocrine morphology (n = 4), the recognition of LCNEC would increase to 93% (n = 26 of 28). An exemplar case can be found in Figure 3C,D.

Validation Using an Independent TMA Tumour Cohort

To validate the hypothesis that ≥2 neuroendocrine IHC markers staining in the diagnostic setting of NSCLC supports the diagnosis of LCNEC, a TMA of an independent tumour cohort was used. Expression of ≥2 neuroendocrine markers in LCNEC was observed in 15 of 19 (79%) and in 18 of 18 (100%) carcinoid and three of three (100%) SCLC tumours, respectively. Staining for ≥2 neuroendocrine markers occurred in only one of 77 (1%) NSCLC cases with strong staining for CD56 and faint staining for synaptophysin. Expression of a single neuroendocrine marker was observed in 11 of 77 (14%) of NSCLC, mostly CD56 (n = 4) or synaptophysin (n = 7). A summary of identified IHC expression patterns can be found in Table 3, specified in the Supporting information, Table S2 and the Supporting information Data S1. Using the current 2015 WHO criteria, only nine of 19 (47%) LCNEC were identified correctly on the TMA cohort (ET).

Table 3.

Overview of neuroendocrine IHC marker staining in adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas and reported clinical relevance

| Authors | TMA | Morphology | Any (+) | CD56 | Chr‐A | Synaptophysin | >2 markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

González Argoneses et al. |

Yes (>10% of cells) |

AdC n = 156 SqCC n = 128 |

– | – | – |

52 (33%) 34 (21%) |

– |

|

Pelosi et al. |

No (median of 2000 cells) |

AdC n = 88 SqCC n = 113 |

15 (17%) 13 (12%) |

– |

0 (0%) 2 (2%) |

3 (4%) 7 (6%) |

– |

|

Segawa et al. |

No (focal or more) |

AdC n = 55 SqCC n = 50 |

15 (27% 4 (8%) |

7 (18%) 2 (4%) |

4 (7%) 1 (2%) |

8 (15%) 0 (0%) |

– |

|

Sterlacci et al. |

Yes (any positivity) |

AdC n = 197 SqCC n = 119 |

38 (19%) 7 (6%) |

10 (5%) 3 (3%) |

2 (1%) 0 (0%) |

28 (16%) 4 (3%) |

– |

|

Hage et al. |

No (UA) |

AdC n = 262 SqCC n = 575 |

– |

30 (11%) 86 (15%) |

– | – | – |

|

Ionescu et al. |

Yes (>1% cell positivity) |

AdC n = 243** SqCC n = 272** |

76 (31%) 83 (31%) |

11 (5%) 29 (12%) |

1 (1%) 1 (1%) |

23 (11%) 10 (4%) |

3 (1%) 2 (1%) |

|

Howe et al. |

Yes (>focal weak) |

NSCLCa n = 341 | 157 (36%) | 44 (28%) | 9 (6%) | 27 (17%) | – |

| Rooper et al. |

Yes (any positivity) |

AdC n = 61 SqCC n = 95 |

8 (13%) 7 (7%) |

3 (5%) 7 (7%) |

1 (2%) 0 (0%) |

4 (7%) 1 (1%) |

– |

| Ye et al. |

Yes (>5% cell positivity) |

AdC n = 183 SqCC n = 101 |

28 (15%) 12 (12%) |

3 (2%) 8 (8%) |

10 (6%) 6 (6%) |

22 (12%) 2 (2%) |

7 (4%) 3 (3%) |

| Derks et al. |

Yes (any positivity) |

AdC n = 33 SqCC n = 29 NSCLC NOS = 15 |

6 (18%) 1 (3%) 4 (27%) |

3 (10%) 1 (3%) 1 (7%) |

0 (0%) 0 (0%) 0 (0%) |

4 (12%) 1 (3%) 2 (13%) |

0 (0%) 0 (0%) 1 (7%) |

| Total |

AdC SqCC NSCLC |

186/860 (22%) 126/808 (15%) 473/2024 (23%) |

67/1034 (6%) 136/1241 (11%) 248/2631 (9%) |

18/860 (2%) 10/808 (1%) 37/2009 (2%) |

140/1016 (14%) 59/907 (7%) 226/2264 (10%) |

10/459 (2%) 5/402 (1%) 15/861 (2%) |

AdC, adenocarcinoma; SqCC, squamous cell carcinoma; Syn, synaptophysin, Chr‐A, chromogranin‐A; UA; unavailable; TMA, tissue microarray.

Combination of morphological differentiated AdC, SqCC, large cell carcinoma and adenosquamous carcinomas.

Discussion

Our retrospective study shows that in biopsy specimens positivity for ≥2 of three neuroendocrine markers may support the diagnosis of LCNEC in cases devoid of neuroendocrine morphology in undifferentiated or TTF1‐positive NSCLC. Adding this IHC criterion to the current WHO classification will increase the sensitivity of the diagnosis of LCNEC on biopsy specimens from 47% to 79–93%, providing an opportunity for better treatment in patients with LCNEC.

As LCNEC is not diagnosed on biopsy specimens, these cases will currently be called adenocarcinoma when TTF1 is positive, or NSCLC not otherwise specified. Our study provided an argument that in smaller biopsies the chance of identifying neuroendocrine morphology is lower than in larger biopsies, explaining the difficulty of diagnosing LCNEC on morphology criteria alone.

In NSCLC neuroendocrine immunohistochemical staining with chromogranin‐A, synaptophysin and CD56 was mainly performed on resection specimens.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Focal IHC staining for one neuroendocrine marker is not infrequent, and has no prognostic or therapeutic relevance. According to the current WHO classification, IHC for neuroendocrine differentiation should therefore not be applied for diagnostic purposes when neuroendocrine morphology is absent.3, 23 The reported range of one of the three neuroendocrine markers in squamous cell carcinomas, and adenocarcinomas are more or less similar (8–31% and 17–33%, respectively, see Table 3).17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 24 Interestingly, positivity for two of the three common neuroendocrine markers in NSCLC is present in only 1–3.8%.18, 24, 25 This suggests that if applied as an additional diagnostic criterion for LCNEC, the specificity of this criterion may be >96%. Positive staining of ≥2 of the three common neuroendocrine markers is reported in ≥80% of LCNEC,26, 27 which is completely in line with the two cohorts evaluated in our study. These data suggest that the sensitivity of this criterion for the diagnosis of LCNEC will be approximately 80%. The high sensitivity and specificity may, if applied in the diagnostic process of LCNEC, lead to an increase in the diagnostic accuracy of LCNEC on biopsy specimens requiring confirmation in further studies.

For the interpretation of neuroendocrine differentiation, care must be taken not to make a false positive call. This may occur in a tumour‐circumvented bronchiole with occasional neuroendocrine cells or by CD56 positivity on intratumoral lymphocytes. Moreover, for judging chromogranin‐A, evaluation of tumour cells at a ×40 objective is essential to detect occasional dot‐like positivity of small cytoplasmic granules, which may not be observed with the ×2.5–10 microscope objective.

Previous studies that aimed to evaluate the LCNEC WHO 2015 criteria on biopsy specimens have shown high diagnostic specificity.7, 8, 9, 10, 11 Similarly, we provide evidence that the specificity for LCNEC on a biopsy specimen is acceptable (i.e. 83%). Nonetheless, we observed that several biopsy specimens diagnosed as LCNEC were classified as SCLC in the resection specimens. This is probably explained by tumour heterogeneity and the difficulty in assessing cytological features in biopsy specimens, as addressed previously.4, 28 This imperfect specificity may affect the results of chemotherapy studies, as was suggested recently.29

Several recently described markers may aid in the differential diagnosis of LCNEC on biopsy specimens and require further evaluation. The insulinoma‐associated protein 1 (INSM1) is a transcription factor of neuroendocrine differentiation proposed as a pan‐neuroendocrine marker that outperforms traditionally used markers, with similar specificity as chromogranin A and comparable sensitivity to CD56 and synaptophysin.30, 31 INSM1 stains 75–91% of LCNEC and focal staining is observed in 0–4% of NSCLC.30, 31, 32 The value of INSM1 in an algorithm of ≥2 neuroendocrine markers staining for biopsies to recognise LCNEC is unclear. Furthermore, recent studies have addressed the existence of different molecular subtypes of LCNEC.27, 33, 34 Proposed are the LCNEC‐SCLC with TP53/RB1 mutations recognised with IHC by loss of the RB1 protein and the LCNEC‐NSCLC subtype with STK11/KEAP/KRAS mutations and the presence of RB1 protein staining.27, 35 In the differential diagnosis of LCNEC versus SCLC, staining of RB1 IHC is indicative of a non‐SCLC‐like tumour.4 Finally, napsin‐A is proposed as a marker to differentiate the TTF1‐positive molecular LCNEC‐NSCLC subtype from adenocarcinoma, as only few show focal staining for napsin‐A while all adenocarcinomas show (strong) staining for both markers.36

Our study was restricted by the limited number of paired biopsy‐resection specimens evaluated by the panel of pathologists. Nevertheless, the described diagnostic issues in this study reflect the daily clinical practice closely. Furthermore, this is the first substantial analysis of the established WHO criteria for LCNEC on biopsy specimens using matched resection specimens.

In conclusion, positivity for two of three traditionally used neuroendocrine IHC stains leads to a useful increase in the diagnostic accuracy of LCNEC on biopsy specimens.

Conflicts of interest

No conflicts of interest to declare.

Supporting information

Data S1. TMA results.

Table S1. Results of structured WHO criteria evaluation in biopsy specimen from surgical resection specimen not diagnosed as LCNEC.

Table S2. Overview of TMA marker results.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the Dutch Cancer Society (UM‐2014‐7110) granted to Professor dr A‐M. C. Dingemans. We would like to acknowledge C. M. Stallinga and G. M. Roemen from the Maastricht University Medical Centre for staining of IHC markers.

PALGA‐Group Co‐Authors

L Arensman, Meander Medisch Centrum Klinische Pathologie; F E Bellot, Klinische Pathologie Hoofddorp; J E Broers, Isala Klinieken; C M van Dish; Klinische pathologie Groene Hart Ziekenhuis; K E S Duthoi, Amphia Ziekenhuis; M J Flens, Symbiant; J M M Grefte, Gelre Ziekenhuis Klinische Pathologie; M C H Hogenes, Labpon; R Natté, Haga Ziekenhuis; A F van Hamel, Pathologie SSZOG; P J J M Klinkhamer, Stichting PAMM; J W R Meijer, Ziekenhijs Rijnstate; J C C van der Meij, Pathologie Friesland; F H van Nederveen Laboratorium voor Pathologie (PAL); E W P Nijhuis, Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis; M F M van Oosterhout, St Antonius Ziekenhuis; S H Sastrowijoto, Pathologie Sittard; K Schelfout, Stichting Pathologisch en Cytologisch Laboratorium West‐Brabant; J Sietsma, Pathologie Martini Ziekenhuis; F M M Smedts, Reinier Haga MDC; M M Smits, Laboratorium voor Klinische Pathologie; J Stavast, Laboratorium Klinische Pathologie Centraal Brabant; W Timens, Pathologie UMCG; M L van Velthuysen, NKI‐AVL; A Vink, Universitair Medisch Centrum Utrecht; C C A P Wauters, Canisius Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis; & S Wouda, VieCuri Medical Centre.

Derks J L, Dingemans A‐M C, van Suylen R‐J, den Bakker M A, Damhuis R A M, van den Broek E C, Speel E‐J, Thunnissen E (2019) Histopathology 74, 555–566. 10.1111/his.13800 Is the sum of positive neuroendocrine immunohistochemical stains useful for diagnosis of large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) on biopsy specimens?

Please see list of PALGA contributors at the end of the paper (Appendix).

References

- 1. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M et al Diagnosis of lung cancer in small biopsies and cytology: implications of the 2011 International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society classification. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2013; 137; 668–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Travis WD, Rekhtman N, Riley GJ et al Pathologic diagnosis of advanced lung cancer based on small biopsies and cytology: a paradigm shift. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010; 5; 411–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Burke AP, Marx A, Nicholson AG. Introduction to the 2015 World Health Organization classification of tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus, and heart. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015; 10; 1240–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Thunnissen E, Borczuk AC, Flieder DB et al The use of immunohistochemistry improves the diagnosis of small cell lung cancer and its differential diagnosis. An international reproducibility study in a demanding set of cases. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017; 12; 334–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Travis WD, Linnoila RI, Tsokos MG et al Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung with proposed criteria for large‐cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. An ultrastructural, immunohistochemical, and flow cytometric study of 35 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1991; 15; 529–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Derks JL, van Suylen RJ, Thunnissen E et al A population‐based analysis of application of WHO nomenclature in pathology reports of pulmonary neuroendocrine tumors. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016; 11; 593–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Igawa S, Watanabe R, Ito I et al Comparison of chemotherapy for unresectable pulmonary high‐grade non‐small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma and small‐cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2010; 68; 438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shimada Y, Niho S, Ishii G et al Clinical features of unresectable high‐grade lung neuroendocrine carcinoma diagnosed using biopsy specimens. Lung Cancer 2012; 75; 368–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watanabe R, Ito I, Kenmotsu H et al Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung: is it possible to diagnose from biopsy specimens? Jpn. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013; 43; 294–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marmor S, Koren R, Halpern M, Herbert M, Rath‐Wolfson L. Transthoracic needle biopsy in the diagnosis of large‐cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung. Diagn. Cytopathol. 2005; 33; 238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Inage T, Nakajima T, Fujiwara T et al Pathological diagnosis of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma by endobronchial ultrasound‐guided transbronchial needle aspiration. Thorac. Cancer 2018; 9; 273–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Masters GA, Temin S, Azzoli CG et al Systemic therapy for stage IV non‐small‐cell lung cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2015; 33; 3488–3515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Derks JL, van Suylen RJ, Thunnissen E et al Chemotherapy for pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas: does the regimen matter? Eur. Respir. J. 2017; 49; 1610838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Casparie M, Tiebosch AT, Burger G et al Pathology databanking and biobanking in The Netherlands, a central role for PALGA, the nationwide histopathology and cytopathology data network and archive. Cell Oncol. 2007; 29; 19–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rindi G, Klersy C, Inzani F et al Grading the neuroendocrine tumors of the lung: an evidence‐based proposal. Endocr. Relat. Cancer 2014; 21; 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fabbri A, Cossa M, Sonzogni A et al Ki‐67 labeling index of neuroendocrine tumors of the lung has a high level of correspondence between biopsy samples and surgical specimens when strict counting guidelines are applied. Virchows Arch. 2017; 470; 153–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pelosi G, Pasini F, Sonzogni A et al Prognostic implications of neuroendocrine differentiation and hormone production in patients with Stage I nonsmall cell lung carcinoma. Cancer 2003; 97; 2487–2497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ionescu DN, Treaba D, Gilks CB et al Nonsmall cell lung carcinoma with neuroendocrine differentiation – an entity of no clinical or prognostic significance. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2007; 31; 26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Howe MC, Chapman A, Kerr K, Dougal M, Anderson H, Hasleton PS. Neuroendocrine differentiation in non‐small cell lung cancer and its relation to prognosis and therapy. Histopathology 2005; 46; 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gonzalez‐Aragoneses F, Moreno‐Mata N, Cebollero‐Presmanes M, et al Prognostic significance of synaptophysin in stage I of squamous carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the lung. Cancer 2007; 110; 1776–1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Segawa Y, Takata S, Fujii M et al Immunohistochemical detection of neuroendocrine differentiation in non‐small‐cell lung cancer and its clinical implications. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2009; 135; 1055–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hage R, Elbers HR, Brutel de la Riviere A, van den Bosch JM. Neural cell adhesion molecule expression: prognosis in 889 patients with resected non‐small cell lung cancer. Chest 1998; 114; 1316–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Travis WD, Brambilla E, Nicholson AG. Testing for neuroendocrine immunohistochemical markers should not be performed in poorly differentiated NSCCs in the absence of neuroendocrine morphologic features according to the 2015 WHO classification. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016; 11; e26–e27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sterlacci W, Fiegl M, Hilbe W, Auberger J, Mikuz G, Tzankov A. Clinical relevance of neuroendocrine differentiation in non‐small cell lung cancer assessed by immunohistochemistry: a retrospective study on 405 surgically resected cases. Virchows Arch. 2009; 455; 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ye B, Cappel J, Findeis‐Hosey J et al hASH1 is a specific immunohistochemical marker for lung neuroendocrine tumors. Hum. Pathol. 2016; 48; 142–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Takei H, Asamura H, Maeshima A et al Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung: a clinicopathologic study of eighty‐seven cases. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002; 124; 285–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rekhtman N, Pietanza MC, Hellmann M et al Next‐generation sequencing of pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma reveals small cell carcinoma‐like and non‐small cell carcinoma‐like subsets. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016; 22; 3618–3629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nicholson SA, Beasley MB, Brambilla E et al Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC): a clinicopathologic study of 100 cases with surgical specimens. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2002; 26; 1184–1197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Grossi G, Longo L, Barbieri F, Bertolini F. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the lung: chemotherapy regimen depends on how ‘large’ are your diagnostic criteria. Eur. Respir. J. 2017; 59; 1701292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Rooper LM, Sharma R, Li QK, Illei PB, Westra WH. INSM1 demonstrates superior performance to the individual and combined use of synaptophysin, chromogranin and CD56 for diagnosing neuroendocrine tumors of the thoracic cavity. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2017; 41; 1561–1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mukhopadhyay S, Dermawan JK, Lanigan CP, Farver CF. Insulinoma‐associated protein 1 (INSM1) is a sensitive and highly specific marker of neuroendocrine differentiation in primary lung neoplasms: an immunohistochemical study of 345 cases, including 292 whole‐tissue sections. Mod. Pathol. 2019; 32; 100–109. 10.1038/s41379-018-0122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Fujino K, Motooka Y, Hassan WA et al Insulinoma‐associated protein 1 is a crucial regulator of neuroendocrine differentiation in lung cancer. Am. J. Pathol. 2015; 185; 3164–3177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. George J, Walter V, Peifer M et al Integrative genomic profiling of large‐cell neuroendocrine carcinomas reveals distinct subtypes of high‐grade neuroendocrine lung tumors. Nat. Commun. 2018; 9; 1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Derks JL, Leblay N, Lantuejoul S, Dingemans AC, Speel EM, Fernandez‐Cuesta L. New insights into the molecular characteristics of pulmonary carcinoids and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, and the impact on their clinical management. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2018; 13; 752–766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Derks JL, Leblay N, Thunnissen E et al Molecular subtypes of pulmonary large‐cell neuroendocrine carcinoma predict chemotherapy treatment outcome. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018; 24; 33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rekhtman N, Pietanza CM, Sabari J et al Pulmonary large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma with adenocarcinoma‐like features: napsin A expression and genomic alterations. Mod. Pathol. 2018; 31; 111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1. TMA results.

Table S1. Results of structured WHO criteria evaluation in biopsy specimen from surgical resection specimen not diagnosed as LCNEC.

Table S2. Overview of TMA marker results.