Abstract

Objectives

To study whether androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), the mainstay treatment for advanced and disseminated prostate cancer, is associated with risk of dementia.

Methods

Risk of dementia in men with prostate cancer primarily managed with ADT or watchful waiting (WW) in the Prostate Cancer Database Sweden, PCBaSe, was compared with that in prostate cancer‐free men, matched on birth year and county of residency. We used Cox regression to calculate the hazard ratios (HRs) for Alzheimer's and non‐Alzheimer's dementia (vascular dementia, dementia secondary to other diseases or unspecified dementias) for different types and duration of ADT and oral antiandrogens (AAs) as well as for men managed with WW.

Results

A total of 25 967 men with prostate cancer and 121 018 prostate cancer‐free men were followed for a median of 4 years. In both groups 6% of the men were diagnosed with dementia. In men with prostate cancer, gonadotropin‐releasing hormone agonist treatment ( HR 1.15, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.07–1.23) and orchiectomy (HR 1.60, 95% CI 1.32–1.93) were associated with an increased risk of dementia, as compared to no treatment in prostate cancer‐free men; however, this increase in risk was only observed for non‐Alzheimer's dementia and occurred from year 1–4 after start of ADT. No increase in risk for any type of dementia was observed for men treated with AAs or for men on WW.

Conclusion

This population‐based cohort study does not support previous observations of an increased risk of Alzheimer's dementia for men on ADT; however, there was a small increase in risk of non‐Alzheimer's dementia.

Keywords: androgen deprivation therapy, dementia, #ProstateCancer, #PCSM, #ADT, #Dementia

Introduction

With age, testosterone levels in men decline and the risk of dementia increases, but it is unclear whether there is any causal relationship between these two observations 1, 2. Low levels of free testosterone, but not total testosterone, have been associated with Alzheimer's dementia 3, 4, and the mean levels of testosterone in men with Alzheimer's dementia have been reported to be slightly lower than in matched controls, although within the normal range 5. Androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is standard treatment for advanced and disseminated prostate cancer 6. The two main types of ADT are GnRH agonists and oral antiandrogen (AA) monotherapy. GnRH agonists lower circulating testosterone levels through medical castration, whereas AAs compete with testosterone at the androgen receptors in the prostate cell and do not decrease circulating levels of testosterone 7.

Androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer has been suggested to be associated with decreased cognitive function 8. Three large studies found an increased risk of Alzheimer's dementia 9 or overall dementia 10, 11. In these studies, men with prostate cancer on ADT were compared with men with prostate cancer not on ADT, making it difficult to determine whether the increased risk of dementia was caused by ADT, by prostate cancer per se, or by the fact that men with undiagnosed dementia were more likely to receive ADT. By contrast, two population‐based studies found no increased risk of dementia 12, 13.

The aim of the present study was to investigate the risk of dementia, separated into Alzheimer's dementia and non‐Alzheimer's dementia, in men with prostate cancer treated with different types of ADT, or watchful waiting (WW: i.e., no initial treatment, but treatment at progression), in comparison with prostate cancer‐free men.

Material and Methods

Data from the Prostate Cancer Database Sweden, PCBaSe, were used, which includes 97% of all Swedish men with prostate cancer registered in the National Cancer Register from 1997 onwards 14, 15. We investigated a cohort of men with a prostate cancer diagnosis after 1 January 2006 who started treatment with a primary GnRH agonist, bilateral orchiectomy, or an AA shortly after the time of diagnosis, or who were managed with WW (these men received ADT or AAs on disease progression). January 2006 was chosen as the start date because the Prescribed Drug Registry started in July 2005, thus allowing a 6‐month run‐in period. Men with metastatic disease on bone imaging or with a PSA level >100 ng/mL and men with a diagnosis of dementia prior to the start of ADT or WW were excluded. For each man with prostate cancer, five prostate cancer‐free men were randomly selected from the general population, with the same year of birth and county of residence as their index case.

The main outcome was dementia, as registered in the National Patient Register, which was further divided into Alzheimer's dementia (International Classification of Diseases [ICD]10: F00) and non‐Alzheimer's dementia (vascular dementia F01), dementia secondary to other diseases (F02) or unspecified dementias (F03). Men with a prescription of cholinesterase inhibitors (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification [ATC] codes N06DA02, N06DA03, N06DA04) according to the Prescribed Drug Registry were also included as having Alzheimer's dementia. ADT was the main exposure variable and was treated as a time‐dependent covariate in the analyses, allowing changes in the type of ADT.

In addition, information was obtained on potential confounders, such as comorbidity, educational level and civil status 16. Comorbidity was classified according to the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), as previously described 17, 18. Educational level was used as an indicator of socio‐economic status and was categorized as low (≤9 years of school), middle (10–12 years) and high (≥13 years) 19. Civil status was categorized as married or unmarried. Follow‐up started at the date for the first dispensed prescription of a GnRH agonist or an AA, or at the date of surgery for men treated with orchiectomy or the date of diagnosis for men on WW. A man was on WW for the time unexposed to ADT. If the first treatment after WW was AA, he was considered as exposed to AA until the date for a filled prescription for a GnRH agonist/orchiectomy 20. When a prescription for a GnRH agonist was filled or orchiectomy was registered, men were regarded as exposed to these treatments until the first dementia diagnosis or the first prescription of cholinesterase inhibitors (indicating dementia), date of emigration, date of death, or end of study (31 December 2014), whichever event came first. Orchiectomy after a period of GnRH treatment was ignored because it was an extremely rare transition 15.

The risk of dementia was estimated by use of hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs, calculated in Cox proportional hazard regression models, with age as a timescale. Proportionality was verified by visual inspection of Schoenfeld residuals. The models were adjusted for comorbidity, education level and civil status. We also investigated the risk of dementia over time by studying the duration of exposure. Men with CCI = 0 or CCI ≥ 1 with and without cardiovascular disease and risk of dementia were studied in a sensitivity analysis.

There might be a selection mechanism in men who undergo orchiectomy because of impaired cognitive function. We therefore analysed the proportions of men treated with different types of ADT who were excluded from the main analysis because they were diagnosed with dementia before start of prostate cancer treatment.

Results

Altogether, 25 967 men with prostate cancer and 121 018 matched prostate cancer‐free men were included in the study (Table 1). Specifically, 7209 men were managed with WW, 3368 received primary AA treatment, 6982 received a primary GnRH agonist and 705 underwent orchiectomy. Subsequently, 7703 of the men initially managed with curative intent or WW converted to ADT or AA treatment. After a median follow‐up of 4.3 years (Q1: 2.8–Q4: 6.3 years), 1640/25 967 men with prostate cancer (6%) and 7432/121 018 prostate cancer‐free men (6%) had been diagnosed with dementia. The mean age at inclusion was 76 years.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of all men with prostate cancer, men with prostate cancer stratified by treatment, and the matched prostate cancer‐free men (no prostate cancer)

| No prostate cancer n = 121 018 | Prostate cancer n = 25 967 | WW n = 7209 | Primary AAs n = 3368 | Primary GnRH agonists n = 6982 | Primary orchiectomy n = 705 | ADT as a result of disease progression n = 7703 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Follow up time, years, mean ( sd ) | 4.5 (2.2) | 4.2 (2.2) | 4.6 (2.2) | 4.2 (2.1) | 3.9 (2.3) | 3.4 (2.2) | 4.2 (2.2) |

| Age at inclusion, years, mean ( sd ) | 76.2 (7.6) | 76.5 (7.6) | 76.3 (7.1) | 76.9 (6.5) | 78.4 (7.3) | 81.6 (5.9) | 74.1 (8.1) |

| Age at inclusion, n (%) | |||||||

| <65 years | 10 232 (8.5) | 2086 (8.0) | 503 (7.0) | 168 (5.0) | 338 (4.8) | 7 (1.0) | 1070 (13.9) |

| 65–74 years | 38 488 (31.8) | 8009 (30.8) | 2310 (32.0) | 977 (29.0) | 1649 (23.6) | 88 (12.5) | 2985 (38.8) |

| 75–79 years | 32 891 (27.2) | 6944 (26.7) | 2056 (28.5) | 1163 (34.5) | 1872 (26.8) | 148 (21.0) | 1705 (22.1) |

| 80–84 years | 25 803 (21.3) | 5724 (22.0) | 1653 (22.9) | 739 (21.9) | 1851 (26.5) | 253 (35.9) | 1228 (15.9) |

| 85 years | 13 604 (11.2) | 3204 (12.3) | 687 (9.5) | 321 (9.5) | 1272 (18.2) | 209 (29.6) | 715 (9.3) |

| CCI at inclusion, n (%) | |||||||

| 0 | 73 912 (61.1) | 15 358 (59.1) | 4422 (61.3) | 1985 (58.9) | 3825 (54.8) | 346 (49.1) | 4780 (62.1) |

| 1 | 22 234 (18.4) | 5131 (19.8) | 1343 (18.6) | 688 (20.4) | 1432 (20.5) | 178 (25.2) | 1490 (19.3) |

| 2 | 13 189 (10.9) | 3056 (11.8) | 845 (11.7) | 381 (11.3) | 927 (13.3) | 103 (14.6) | 800 (10.4) |

| 3+ | 11 683 (9.7) | 2422 (9.3) | 599 (8.3) | 314 (9.3) | 798 (11.4) | 78 (11.1) | 633 (8.2) |

| Year of follow up start, n (%) | |||||||

| 2006–2008 | 53 451 (44.2) | 11 444 (44.1) | 3107 (43.1) | 1169 (34.7) | 3397 (48.7) | 395 (56.0) | 3376 (43.8) |

| 2009–2010 | 35 820 (29.6) | 7673 (29.5) | 2292 (31.8) | 1035 (30.7) | 1998 (28.6) | 208 (29.5) | 2140 (27.8) |

| 2011–2012 | 31 747 (26.2) | 6850 (26.4) | 1810 (25.1) | 1164 (34.6) | 1587 (22.7) | 102 (14.5) | 2187 (28.4) |

| Prostate cancer risk category*, n (%) | |||||||

| No prostate cancer | 121 018 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Low risk | 0 (0.0) | 3430 (13.2) | 1586 (22.0) | 140 (4.2) | 154 (2.2) | 4 (0.6) | 1546 (20.1) |

| Intermediate risk | 0 (0.0) | 7436 (28.6) | 2742 (38.0) | 795 (23.6) | 1041 (14.9) | 91 (12.9) | 2767 (35.9) |

| High risk | 0 (0.0) | 10 618 (40.9) | 1889 (26.2) | 1794 (53.3) | 3823 (54.8) | 383 (54.3) | 2729 (35.4) |

| Regionally metastatic | 0 (0.0) | 3489 (13.4) | 229 (3.2) | 605 (18.0) | 1900 (27.2) | 223 (31.6) | 532 (6.9) |

| Missing data | 0 (0.0) | 994 (3.8) | 763 (10.6) | 34 (1.0) | 64 (0.9) | 4 (0.6) | 129 (1.7) |

| Educational level, n (%) | |||||||

| Low | 56 131 (46.4) | 11 918 (45.9) | 3308 (45.9) | 1514 (45.0) | 3618 (51.8) | 430 (61.0) | 3048 (39.6) |

| Middle | 41 003 (33.9) | 9123 (35.1) | 2556 (35.5) | 1181 (35.1) | 2290 (32.8) | 188 (26.7) | 2908 (37.8) |

| High | 21 456 (17.7) | 4646 (17.9) | 1266 (17.6) | 637 (18.9) | 976 (14.0) | 74 (10.5) | 1693 (22.0) |

| Missing | 2428 (2.0) | 280 (1.1) | 79 (1.1) | 36 (1.1) | 98 (1.4) | 13 (1.8) | 54 (0.7) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||||||

| Married | 78 413 (64.8) | 17 382 (66.9) | 4716 (65.4) | 2248 (66.7) | 4357 (62.4) | 411 (58.3) | 5650 (73.3) |

| Not married | 42 605 (35.2) | 8585 (33.1) | 2493 (34.6) | 1120 (33.3) | 2625 (37.6) | 294 (41.7) | 2053 (26.7) |

AA, antiandrogen; ADT, androgen deprivation therapy; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; WW, watchful waiting. *Modified National Comprehensive Cancer Network classification.

Men on WW and men on AA were not more likely than the men without prostate cancer to be diagnosed with dementia: HR 0.99 (95% CI 0.89–1.10) and 0.94 (95% CI 0.84–1.05), respectively (Table 2). Treatment with GnRH agonists (HR 1.15 [95% CI 1.07–1.23]) and orchiectomy (HR 1.60 [95% CI 1.32–1.93]) were both associated with risk of developing any dementia as compared to no treatment in the prostate cancer‐free men (Table 2). In a separate analysis of risk of Alzheimer's and non‐Alzheimer's dementia, there was a significant risk increase of non‐Alzheimer's dementia only: GnRH agonists (HR 1.24 [95% CI 1.14–1.36]) and orchiectomy (HR 1.79 [95% CI 1.42–2.25]; Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of events (diagnosis of all dementia, Alzheimer's dementia and non‐Alzheimer's dementia) in men without prostate cancer and in men on watchful waiting, antiandrogen treatment, GnRH agonist treatment and who underwent orchiectomy

| Number of events | Number of events* Drug/F00/F01/F02/F03 | Incidence | Crude HR | HR after adjustment, CCI, educational level and civil status | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All dementia | |||||||

| No prostate cancer | 7432 | 2964/378/1106/79/2905 | 13.6 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Reference |

| WW | 359 | 148/21/56/4/130 | 13.2 | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 | 0.99 | 0.89–1.10 |

| AAs | 330 | 141/22/47/6/114 | 10.9 | 0.93 | 0.84–1.04 | 0.94 | 0.84–1.05 |

| GnRH agonists | 841 | 293/32/123/3/390 | 17.5 | 1.15 | 1.07–1.24 | 1.15 | 1.07–1.23 |

| Orchidectomy | 110 | 34/3/11/0/62 | 31.6 | 1.61 | 1.34–1.95 | 1.60 | 1.32–1.93 |

| Alzheimer's dementia | |||||||

| No prostate cancer | 3342 | 2964/378/0/0/0 | 6.1 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Reference |

| WW | 169 | 148/21/0/0/0 | 6.2 | 1.01 | 0.87–1.18 | 1.01 | 0.86–1.18 |

| AAs | 163 | 141/22/0/0/0 | 5.4 | 0.97 | 0.83–1.14 | 0.97 | 0.83–1.14 |

| GnRH agonists | 325 | 293/32/0/0/0 | 6.8 | 1.02 | 0.91–1.14 | 1.02 | 0.91–1.14 |

| Orchidectomy | 37 | 34/3/0/0/0 | 10.6 | 1.33 | 0.96–1.84 | 1.33 | 0.96–1.84 |

| Non‐Alzheimer's dementia | |||||||

| No prostate cancer | 4090 | 0/0/1106/79/2905 | 7.5 | 1.00 | Ref. | 1.00 | Reference |

| WW | 190 | 0/0/56/4/130 | 7.0 | 0.96 | 0.83–1.11 | 0.98 | 0.84–1.13 |

| AAs | 167 | 0/0/47/6/114 | 5.5 | 0.90 | 0.77–1.05 | 0.91 | 0.78–1.06 |

| GnRH agonists | 516 | 0/0/123/3/390 | 10.7 | 1.25 | 1.14–1.37 | 1.24 | 1.14–1.36 |

| Orchidectomy | 73 | 0/0/11/0/62 | 21.0 | 1.81 | 1.44–2.28 | 1.79 | 1.42–2.25 |

AA, antiandrogen; ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification; CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; HR, hazard ratio; ICD, International Classification of Diseases; WW, watchful waiting. *Number of events subdivided into men who had received a prescription of cholinesterase inhibitors (ATC codes N06DA02, N06DA03, N06DA04), registered as drug against Alzheimer's dementia in the Prescribed Drug Registry. ICD10 codes: F00, Alzheimer's dementia and non‐Alzheimer's dementia (vascular dementia F01), dementia secondary to other diseases (F02) or unspecified dementias (F03) from the National Patient Register. Incidence per 1000 person‐years. Crude HR with 95% CI.

The incidence of non‐Alzheimer's dementia was 7.5/1000 person‐years among prostate cancer‐free men and 10.7/1000 person‐years in men on GnRH agonists, whereas the incidence of Alzheimer's dementia was similar in these two groups (Table 2). The results from the sensitivity analyses for men with CCI = 0 or CCI ≥ 1, with and without cardiovascular disease, supported the main analysis ([Link], [Link], [Link], [Link]).

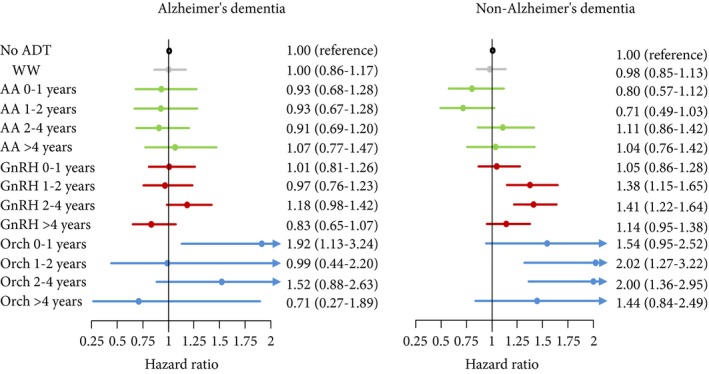

The temporal analysis showed no change in the risk of non‐Alzheimer's dementia during the first year of treatment with GnRH agonists and during the first year after orchiectomy; however, there was a significant increase in risk after 1–2 years (HR 1.38 [95% CI 1.15–1.65]) and 2–4 years (HR 1.41 [95% CI 1.22–1.62]) of treatment. After more than 4 years of observation the risk decreased again (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Risk of dementia related to the duration of exposure by use of hazard ratios with 95% CIs, calculated in Cox proportional hazard regression models with age as a timescale. Men without prostate cancer were the reference group. AA, antiandrogen; Orch, orchiectomy;WW, watchful waiting.

The proportions of men treated with orchiectomy, GnRH agonists, AAs and WW who were excluded from the main analysis because they were diagnosed with dementia before start of prostate cancer treatment were 3.3%, 1.7%, 1.2% and 1.8%, respectively.

Discussion

We found no association between ADT and Alzheimer's dementia or between AA treatment and non‐Alzheimer's dementia in this large population‐based cohort study; however, there was a weak association between use of GnRH agonist, orchiectomy and risk of non‐Alzheimer's dementia. Men with prostate cancer managed with WW had a similar risk of Alzheimer's dementia and non‐Alzheimer's dementia to that of prostate cancer‐free men.

Previous studies analysed the association between ADT and any dementia or Alzheimer's dementia in men with prostate cancer using men with prostate cancer but unexposed to ADT as reference 9, 10, 11. These studies reported an increased risk of Alzheimer's dementia (HR 1.66 [95% CI 1.05–2.64]) and any dementia (HR 2.21 [95% CI 1.72–2.83] and HR 1.17 [95% CI 1.08–1.27]). By contrast, recent studies found no increase in risk of dementia in men on ADT for non‐metastatic prostate cancer compared to men with prostate cancer not treated with ADT: HR 1.02 (95% CI 0.87–1.19) and HR 1.04 (95% CI 0.94–1.16) 12, 13. The mean age was 70–71 years in these studies, whereas in the present study the mean age was 76 years 9, 10, 12.

Two previous studies of the association between ADT and cognitive impairment have reported conflicting results 8, 21. Both these studies were prospective and included men on ADT, men with prostate cancer not on ADT, and prostate cancer‐free men with a follow‐up of 1 year 12. A meta‐analysis of the effect of ADT on performance according to seven cognitive domains reported that visual‐spatial ability was the only affected domain 22. Finally, a recent meta‐analysis between overall cognitive impairment and use of ADT was inconclusive 23.

In the present study, men who underwent orchiectomy had the highest risk of a diagnosis of non‐Alzheimer's dementia, followed by men on GnRH agonists. Since these treatments both lower testosterone levels to castrate levels, the likely explanation for this difference is selection bias. A higher proportion of men excluded from the main study because of a diagnosis of dementia before the date of the prostate cancer diagnosis underwent orchidectomy compared to GnRH agonist treatment (3.3% vs 1.7%). This suggests that men with pretreatment cognitive impairment with a higher risk of a subsequent diagnosis of dementia were more likely to undergo orchiectomy. In addition, selection bias may also explain the difference observed between AA and GnRH agonist treatment; however, as there was no association with dementia in men on WW, a group of men who are generally less healthy and have a limited life expectancy, selection bias may not be the only reason for an increased risk of dementia in men on GnRH agonists.

A putative mechanism behind an increased risk of non‐Alzheimer's dementia in men on ADT is unclear. According to the Swedish guidelines for prostate cancer care, men on monotherapy with AAs, GnRH agonists and WW should have the same intervals of follow‐up. However, we observed an increased risk of non‐Alzheimer's dementia only for men who had received medical or surgical castration therapy, but not for men on AA or WW, suggesting that our results were not caused by ascertainment bias.

Risk increase was only observed for a limited time after initiation of ADT. We can speculate that ADT may facilitate an already ongoing process and decrease time to dementia diagnosis; for example, such a process could be existing vascular disease. Cardiovascular disease in general has been shown to be more common in men on ADT 24, 25. An alternative explanation for our results is that, while Alzheimer's dementia is based on firm criteria 26, non‐Alzheimer's dementia mainly consists of unspecified dementias (F03), and the size of this group of patients could be inflated by other, clinically similar diagnoses. For instance, depression could be misdiagnosed as unspecified dementia because of the lack of distinct diagnostic criteria for the latter disease. There is an increased risk of depression in men on ADT, and depression, cognitive impairment and dementia are interrelated in complex ways 27, 28, 29. As the present study is register‐based, the validity of dementia diagnosis is a concern; however, in a study using the National Patient Registry, the validity of dementia diagnosis was 95% 30. Any potential misclassification would be non‐differential as it is unlikely that classification of dementia would differ according to ADT or if a man was included as a prostate cancer‐free control.

The strengths of the present study include its population‐based design, its size and the comparisons with matched prostate cancer‐free men that allowed us to also assess the association between prostate cancer per se and dementia. This design allows the assessment and elimination of several potential sources of bias that may affect our analysis. Furthermore, the large number of men treated with ADT allowed us to differentiate different forms and durations of ADT.

A limitation of the present study is that we could not assess the indication for selection of treatment with AAs or GnRH agonists; however, we did account for this as much as possible by considering age and CCI. We are aware of the uncertainties regarding validity in the present study, as well as in other observational studies, and that only a randomized trial can completely exclude confounding. One way to address confounding beyond modelling is to restrict analyses to strata where confounding is minimal. The analyses presented in Tables S1–S4 show results in strata where confounding, if present, would be greatly reduced. These results do not indicate that our results were attributable to confounding.

In conclusion, this population‐based cohort study does not support previous observations of an increased risk of Alzheimer's dementia for men on ADT; however, there was a small increase in risk of non‐Alzheimer's dementia. The association between ADT, depression and non‐Alzheimer's dementia, needs to be elucidated in future studies.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Abbreviations

- ADT

androgen deprivation therapy

- WW

watchful waiting

- HR

hazard ratio

- ICD

International Classification of Diseases

- CCI

Charlson comorbidity index

Supporting information

Table S1. Sensitivity analysis with restriction to men with CCI = 0 without underlying cardiovascular disease/medications for cardiovascular disease.

Table S2. Sensitivity analysis with restriction to men with CCI = 1 or higher without underlying cardiovascular disease/medications for cardiovascular disease.

Table S3. Sensitivity analysis with restriction to men with underlying cardiovascular disease/medications for cardiovascular disease in pts with CCI = 0.

Table S4. Sensitivity analysis with restriction to men with an underlying cardiovascular disease/medication for cardiovascular disease in pts with CCI = 1 or higher.

Acknowledgements

Hans Garmo had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. This project was made possible by the continuous work of the National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden (NPCR) steering group: Pär Stattin (chairman), Anders Widmark, Camilla Thellenberg, Ove Andrén, Eva Johansson, Ann‐Sofi Fransson, Magnus Törnblom, Stefan Carlsson, Marie Hjälm Eriksson, David Robinson, Mats Andén, Johan Stranne, Jonas Hugosson, Ingela Franck Lissbrant, Maria Nyberg, Calle Waller, Per Fransson, Fredrik Sandin and Karin Hellström. The study was supported by the Swedish Research Council 825‐2012‐5047, the Swedish Cancer Society 16‐0700, 16‐286, 16‐464. Uppsala County Council, Clinical Cancer Research Foundation in Jönköping, the Stockholm Cancer Society and the Prostate Cancer Association. None of these funders had any part in the collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data, nor in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, Pearson J, Blackman MR, Baltimore Longitudinal Study of A . Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2001; 86: 724–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Satizabal CL, Beiser AS, Chouraki V, Chene G, Dufouil C, Seshadri S. Incidence of dementia over three decades in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med 2016; 374: 523–32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moffat SD, Zonderman AB, Metter EJ et al. Free testosterone and risk for Alzheimer disease in older men. Neurology 2004; 62: 188–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hogervorst E, Bandelow S, Combrinck M, Smith AD. Low free testosterone is an independent risk factor for Alzheimer's disease. Exp Gerontol 2004; 39: 1633–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Butchart J, Birch B, Bassily R, Wolfe L, Holmes C. Male sex hormones and systemic inflammation in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2013; 27: 153–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. NCCN Guidelines for Prostate Cancer. 2016. Available at: http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Accessed April 2017.

- 7. Kunath F, Grobe HR, Rucker G et al. Non‐steroidal antiandrogen monotherapy compared with luteinising hormone‐releasing hormone agonists or surgical castration monotherapy for advanced prostate cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 6: CD009266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gonzalez BD, Jim HSL, Booth‐Jones M et al. Course and predictors of cognitive function in patients with prostate cancer receiving androgen‐deprivation therapy: a controlled comparison. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 2021–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nead KT, Gaskin G, Chester C et al. Androgen deprivation therapy and future Alzheimer's disease risk. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 566–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nead KT, Gaskin G, Chester C, Swisher‐McClure S, Leeper NJ, Shah NH. Association between androgen deprivation therapy and risk of dementia. JAMA Oncol 2017; 3: 49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tae BS, Jeon BJ, Shin SH, Choi H, Bae JH, Park JY. Correlation of androgen deprivation therapy with cognitive dysfunction in patients with prostate cancer: a nationwide population‐based study using the national health insurance service database. Cancer Res Treat 2018. 10.4143/crt.2018.119. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khosrow‐Khavar F, Rej S, Yin H, Aprikian A, Azoulay L. Androgen deprivation therapy and the risk of dementia in patients with prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017; 35: 201–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Deka R, Simpson DR, Bryant AK et al. Association of androgen deprivation therapy with dementia in men with prostate cancer who receive definitive radiation therapy. JAMA Oncol 2018; 4: 1616–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Van Hemelrijck M, Wigertz A, Sandin F et al. Cohort profile: the national prostate cancer register of Sweden and prostate cancer data base Sweden 2.0. Int J Epidemiol 2013; 42: 956–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Van Hemelrijck M, Garmo H, Wigertz A, Nilsson P, Stattin P. Cohort profile update: The National Prostate Cancer Register of Sweden and Prostate Cancer data Base–a refined prostate cancer trajectory. Int J Epidemiol 2016; 45: 73–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xu W, Tan L, Wang H‐F et al. Meta‐analysis of modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2015; 86: 1299–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987; 40: 373–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Berglund A, Garmo H, Tishelman C, Holmberg L, Stattin P, Lambe M. Comorbidity, treatment and mortality: a population based cohort study of prostate cancer in PCBaSe Sweden. J Urol 2011; 185: 833–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berglund A, Garmo H, Robinson D et al. Differences according to socioeconomic status in the management and mortality in men with high risk prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48: 75–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Grundmark B, Garmo H, Zethelius B, Stattin P, Lambe M, Holmberg L. Anti‐androgen prescribing patterns, patient treatment adherence and influencing factors; results from the nationwide PCBaSe Sweden. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2012; 68: 1619–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Alibhai SM, Breunis H, Timilshina N et al. Impact of androgen‐deprivation therapy on cognitive function in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 5030–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. McGinty HL, Phillips KM, Jim HSL et al. Cognitive functioning in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Support Care Cancer 2014; 22: 2271–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sun M, Cole AP, Hanna N et al. Cognitive impairment in men with prostate cancer treated with androgen deprivation therapy: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. J Urol 2018; 199: 1417–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Van Hemelrijck M, Garmo H, Holmberg L et al. Absolute and relative risk of cardiovascular disease in men with prostate cancer: results from the Population‐Based PCBaSe Sweden. J Clin Oncol 2010; 28: 3448–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keating NL, O'Malley A, Freedland SJ, Smith MR. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease during androgen deprivation therapy: observational study of veterans with prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst 2012; 104: 1518–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer's disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2011; 7: 263–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bennett S, Thomas AJ. Depression and dementia: cause, consequence or coincidence? Maturitas 2014; 79: 184–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dinh KT, Reznor G, Muralidhar V et al. Association of androgen deprivation therapy with depression in localized prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 1905–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Lee M, Jim HS, Fishman M et al. Depressive symptomatology in men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: a controlled comparison. Psychooncology 2015; 24: 472–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nordstrom P, Nordstrom A, Eriksson M, Wahlund LO, Gustafson Y. Risk factors in late adolescence for young‐onset dementia in men: a nationwide cohort study. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 1612–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Sensitivity analysis with restriction to men with CCI = 0 without underlying cardiovascular disease/medications for cardiovascular disease.

Table S2. Sensitivity analysis with restriction to men with CCI = 1 or higher without underlying cardiovascular disease/medications for cardiovascular disease.

Table S3. Sensitivity analysis with restriction to men with underlying cardiovascular disease/medications for cardiovascular disease in pts with CCI = 0.

Table S4. Sensitivity analysis with restriction to men with an underlying cardiovascular disease/medication for cardiovascular disease in pts with CCI = 1 or higher.