Abstract

Objectives:

We sought to evaluate the patterns of use and outcomes associated with eptifibatide and abciximab administration among dialysis patients who underwent PCI.

Background:

Contraindicated medications are frequently administered to dialysis patients undergoing PCI often resulting in adverse outcomes. Eptifibatide is a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor that is often used during PCI and is contraindicated in dialysis.

Methods:

We included dialysis patients who underwent PCI from 1/2010 – 9/2015 at 47 hospitals in Michigan. We compared outcomes between patients who received eptifibatide compared with abciximab. Both groups required concurrent treatment with unfractionated heparin only. In-hospital outcomes included repeat PCI, bleeding, major bleeding, need for transfusion, and death. Optimal full matching was used to adjust for non-random drug administration.

Results:

Of 177,963 patients who underwent PCI, 4,303 (2.4%) were on dialysis. Among those, 384 (8.9%) received eptifibatide and 100 (2.3%) received abciximab. Prior to matching, patients who received eptifibatide had higher pre-procedural hemoglobin levels (11.3 g/dL vs. 10.7 g/dL; P < 0.001) and less frequently had a history of myocardial infarction (36.5% vs. 52.0%; P = 0.005). After matching, there were no significant differences in in-hospital outcomes between eptifibatide and abciximab including transfusion (aOR: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.55–2.40; P=0.70), bleeding (1.47; 0.64–3.40; P=0.36), major bleeding (4.68; 0.42–52.3; P=0.21), repeat PCI (0.38; 0.03–4.23; P=0.43), and death (1.53; 0.2–9.05; P=0.64).

Conclusions:

Despite being contraindicated in dialysis, eptifibatide was used approximately 3.5 times more frequently than abciximab among dialysis patients undergoing PCI but was associated with similar in-hospital outcomes.

Keywords: glycoprotein inhibitors, outcomes, bleeding, transfusion, PCI, dialysis

Introduction

Due to the high prevalence of cardiovascular disease among patients with kidney disease,1 this population frequently undergoes cardiovascular procedures such as percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) where they are at an increased risk of post-procedural bleeding and death compared with patients without kidney disease.2–6 Paradoxically, patients on dialysis are also at an increased risk of thrombosis.7 Therefore, research devoted to defining the optimal antithrombotic regimen during PCI in this population is needed. Unfortunately, due to the under-representation or exclusion of patients with kidney disease from cardiovascular randomized clinical trials,8 there remains a remarkable dearth of evidence guiding treatment in this population.

Further complicating this issue is the fact that many medications are metabolized and excreted by the kidney, thereby placing these patients at risk of receiving contraindicated medications.9–11 One such drug is eptifibatide – a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor (GPI) that has been shown to reduce ischemic complications during and after PCI.12, 13 Per the manufacturer’s labeling, eptifibatide is contraindicated in dialysis as its “safety and efficacy” has not been established in these patients.14 In a landmark paper by Tsai et al., the authors demonstrated that nearly a quarter of dialysis patients undergoing PCI received eptifibatide or low molecular weight heparin, two contraindicated medications in dialysis. Furthermore, they found that administration of contraindicated medications was associated with an increased risk of in-hospital major bleeding.9

Due to this important and alarming statistic, most would agree that efforts should be made to reduce the use of contraindicated medications during PCI in patients on dialysis. As such, we sought to evaluate the contemporary use of eptifibatide in dialysis patients undergoing PCI, and to assess the comparative safety of eptifibatide compared with abciximab in these patients using a multicenter registry in the state of Michigan.

Methods

Study population

We performed a retrospective analysis on data from the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2), a quality improvement group and regional registry of all patients undergoing PCI in the state of Michigan. A more detailed description of the registry, including data collection and auditing practices, has been described previously.15, 16 This is a prospective, multicenter, statewide registry of patients undergoing PCI at all non-federal hospitals in Michigan. For the current study, consecutive patients undergoing PCI between January 2010 and September 2015 at 47 hospitals were included.

Study Groups

We divided patients into two groups by the use of renal dialysis. Patients were considered to require dialysis if they were “undergoing either hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis on an ongoing basis as a result of renal failure” prior to PCI.17 To compare the safety of abciximab and eptifibatide, we stratified dialysis patients by these two drugs. Next, we excluded patients who received a GPI with any anticoagulant other than unfractionated heparin (UFH) to reduce bias associated with differential anticoagulant administration. Patients receiving low molecular weight heparin or fondaparinux were excluded because low molecular weight heparin is contraindicated in dialysis and fondaparinux is rarely used during PCI. We excluded patients who received bivalirudin and a GPI because GPIs are frequently administered with bivalirudin as a “bailout” strategy for the treatment of suboptimal procedural results or complications, thereby representing a high-risk subgroup of patients.18 Finally, patients who underwent PCI without recorded femoral or radial access were also excluded.

Clinical outcomes

All outcomes were measured during the incident hospitalization when PCI was performed. In-hospital outcomes included the need for transfusion, bleeding, presumed major bleeding, repeat PCI, and mortality due to any cause. The need for transfusion was defined as the receipt of ≥1 unit of red blood cell or whole blood transfusion after PCI. Bleeding, as defined by the National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR), included an event within 72 hours of PCI that was associated with any of the following: a drop in hemoglobin ≥3 g/dL; transfusion of whole blood or packed red blood cells; an intervention or surgery at the site of bleeding to reverse, stop, or correct the bleeding.17 Presumed major bleeding was defined as a reduction in the patient’s pre-procedural hemoglobin value by >5 g/dL. Repeat PCI was defined as repeat intervention during the incident hospitalization on the lesion that was initially treated.

Statistical analysis

Propensity scores were estimated using logistic regression models adjusting for baseline demographic and patient clinical variables (supplemental table 1). Using optimal full matching methods, we created matched patient strata of patients who were generally similar in terms of baseline characteristics. These strata contained varying numbers of patients with (cases) and without (controls) the covariate of interest (abciximab or eptifibatide).19 Optimal full matching allows treatment group members to share control group members resulting in the use of many more subjects than would be the case if pairwise or “greedy” matching were used.19 We required exact matching on race (white vs. non-white), coronary artery disease (CAD) presentation (ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI], non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI], unstable angina, stable angina, or other), cardiogenic shock within 24 hours prior to or at the start of PCI, prior coronary artery bypass grafting, pre-procedural cardiac arrest, and use of an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) or other mechanical ventricular support devices. Absolute standardized differences (ASDs) were estimated for each variable and a 10% threshold for ASD was used as an indicator of residual imbalance. We then used conditional logistic regression models accounting for these matched patient strata to assess for independent associations between procedural GPI administration and in-hospital outcomes.

Baseline characteristics were reported as means for continuous variables and proportions for categorical variables. Differences between groups were compared using Fisher’s exact testing for categorical variables and Student t tests for continuous variables. All analyses were performed using R version 3.2.1.20

Results

Between January 2010 and September 2015, a total of 177,963 PCIs were performed at 47 hospitals throughout Michigan. Among those, 4,303 (2.4%) were performed in patients on dialysis. The baseline characteristics of patients stratified by dialysis use are demonstrated in Table 1. Patients on dialysis had more comorbid conditions and experienced significantly worse outcomes after PCI, including increased rates of blood transfusions (11.9% vs. 2.7%; P < 0.001), bleeding (4.4% vs. 2.8%; P <0.001), and death (3.5% vs. 1.5%; P <0.001). Notably, patients on dialysis less frequently experienced major bleeding compared with patients not on dialysis (0.6% vs. 1.2%; P <0.001). The most frequent site of arterial access in dialysis patients was the femoral artery (90.3%).

Table 1:

Baseline characteristics and outcomes of patients by dialysis use.

| Variable | On dialysis (n=4,303) | Not on dialysis (n=173,660) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age (years) | 65.23 ± 11.37 | 65.06 ± 12.04 | 0.35 |

| Male gender | 2,573/4,303 (59.8%) | 115,853/173,658 (66.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.17 ± 8.73 | 30.62 ± 7.53 | < 0.001 |

| White race | 2,708/4,303 (62.9%) | 150,543/173,660 (86.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Black or African American race | 1,460/4,303 (33.9%) | 18,375/173,660 (10.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Current/recent smoker (within 1 year) | 837/4,299 (19.5%) | 51,038/173,579 (29.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 4,182/4,300 (97.3%) | 147,813/173,600 (85.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 3,727/4,294 (86.8%) | 142,400/173,505 (82.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Family history of premature CAD | 586/4,301 (13.6%) | 31,486/173,606 (18.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Prior MI | 2,086/4,303 (48.5%) | 60,363/173,626 (34.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Prior heart failure | 2,301/4,301 (53.5%) | 27,032/173,587 (15.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Prior valve surgery/procedure | 131/4,298 (3.0%) | 3,022/173,575 (1.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Prior PCI | 2,311/4,303 (53.7%) | 78,780/173,629 (45.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Prior CABG | 1,035/4,302 (24.1%) | 31,911/173,609 (18.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1,347/4,298 (31.3%) | 26,314/173,592 (15.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 1,655/4,300 (38.5%) | 27,078/173,600 (15.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic lung disease | 1,242/4,299 (28.9%) | 32,541/173,593 (18.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 3,143/4,303 (73.0%) | 64,990/173,619 (37.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Heart failure within 2 Weeks | 1,391/4,300 (32.3%) | 18,587/173,586 (10.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiomyopathy or left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 948/4,302 (22.0%) | 17,911/173,618 (10.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiogenic shock within 24 Hours | 127/4,303 (3.0%) | 3,069/173,610 (1.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest within 24 Hours | 84/4,303 (2.0%) | 3,370/173,578 (1.9%) | 0.96 |

| Pre-PCI left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 47.45 ± 14.52 | 52.03 ± 12.76 | < 0.001 |

| Pre-procedure hemoglobin (g/dL) | 10.76 ± 1.79 | 13.50 ± 1.88 | < 0.001 |

| CAD Presentation | |||

| No symptom, no angina | 336/4,303 (7.8%) | 8,805/173,615 (5.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Symptom unlikely to be ischemic | 121/4,303 (2.8%) | 4,037/173,615 (2.3%) | 0.037 |

| Stable angina | 412/4,303 (9.6%) | 22,827/173,615 (13.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Unstable angina | 1,687/4,303 (39.2%) | 73,331/173,615 (42.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Non-STEMI | 1,455/4,303 (33.8%) | 36,673/173,615 (21.1%) | < 0.001 |

| STEMI or equivalent | 292/4,303 (6.8%) | 27,942/173,615 (16.1%) | < 0.001 |

| P2Y12 Inhibitor Administration | |||

| Pre-procedural clopidogrel | 1,992/4,303 (46.3%) | 61,108/173,660 (35.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Pre-procedural prasugrel | 93/4,303 (2.2%) | 6,013/173,660 (3.5%) | < 0.001 |

| Pre-procedural ticagrelor1 | 51/2,134 (2.4%) | 2,849/81,870 (3.5%) | 0.006 |

| Procedural Characteristics | |||

| Intra-aortic balloon pump | 124/4,301 (2.9%) | 4,399/173,616 (2.5%) | 0.150 |

| Other mechanical ventricular support | 91/4,298 (2.1%) | 1,471/173,586 (0.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Femoral artery access site | 3,838/4,302 (89.2%) | 138,287/173,621 (79.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Radial artery access site | 438/4,302 (10.2%) | 34,739/173,621 (20.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Cardiogenic Shock at Start of PCI | 133/4,301 (3.1%) | 3,578/173,543 (2.1%) | < 0.001 |

| PCI Indication | |||

| Immediate PCI for STEMI | 250/4,302 (5.8%) | 25,043/173,617 (14.4%) | < 0.001 |

| PCI for STEMI (Unstable, >12 hours from symptom onset) | 28/4,302 (0.7%) | 1,418/173,617 (0.8%) | 0.23 |

| PCI for STEMI (Stable, >12 hours from symptom onset) | 21/4,302 (0.5%) | 451/173,617 (0.3%) | 0.004 |

| PCI for STEMI (Stable after successful full-dose thrombolysis) | 1/4,302 (0.0%) | 556/173,617 (0.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Rescue PCI for STEMI (after failed full-dose thrombolytics) | 4/4,302 (0.1%) | 906/173,617 (0.5%) | < 0.001 |

| PCI for high risk Non-STEMI or unstable angina | 2,826/4,302 (65.7%) | 98,409/173,617 (56.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Staged PCI | 162/4,302 (3.8%) | 7,525/173,617 (4.3%) | 0.070 |

| Other | 1,010/4,302 (23.5%) | 39,309/173,617 (22.6%) | 0.196 |

| In-hospital Outcomes | |||

| Stent thrombosis | 5/4,303 (0.1%) | 328/173,660 (0.2%) | 0.28 |

| Repeat PCI | 24/4,303 (0.6%) | 724/173,660 (0.4%) | 0.158 |

| Major bleeding | 23/3,911 (0.6%) | 1,758/144,904 (1.2%) | < 0.001 |

| Blood transfusion | 510/4,299 (11.9%) | 4,745/173,563 (2.7%) | < 0.001 |

| Bleeding | 189/4,299 (4.4%) | 4,852/173,560 (2.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Death | 151/4,303 (3.5%) | 2,523/173,660 (1.5%) | < 0.001 |

Data are presented as n/N (%) or mean ± standard deviation where appropriate.

Data on ticagrelor administration was collected beginning on January 1, 2013.

Abbreviations: CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD=coronary artery disease; IABP=intra-aortic balloon pump; MI=myocardial infarction; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

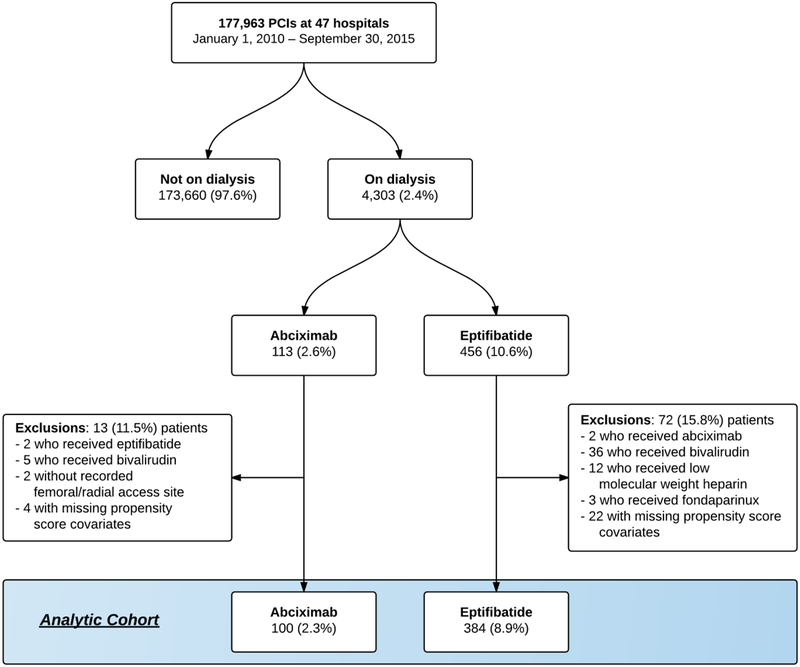

Of the 4,303 patients on dialysis who underwent PCI, 113 received abciximab and 456 received eptifibatide. Of those, a total of 13 (11.5%) patients in the abciximab group and 72 (15.8%) patients in the eptifibatide group met at least one exclusion criteria (Figure 1), leaving 100 and 384 patients in the abciximab and eptifibatide groups, respectively. Patients who received eptifibatide were more frequently white (66.7% vs. 45.0%; P <0.001); had higher pre-procedural hemoglobin levels (11.3 g/dL vs. 10.7 g/dL; P <0.001); and less frequently had a history of myocardial infarction (36.5% vs. 52.0%; P=0.005) (Table 2). Prior to matching, there were no significant differences among in-hospital outcomes between patients treated with eptifibatide compared with abciximab: need for transfusion (18.8% vs. 18.0%; P=0.86), bleeding (10.2% vs. 10.0%; P=0.96), major bleeding (1.3% vs. 2.0%; P=0.60), repeat PCI (1.3% vs. 1.0%; P=0.81), and death (4.4% vs. 8.0%; P=0.15).

Figure 1: Study flow diagram.

Abbreviations: PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention

Table 2:

Baseline characteristics of dialysis patients receiving eptifibatide versus abciximab before and after matching.

| Before matching | After matching | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eptifibatide (n=384) | Abciximab (n=100) | Standardized difference (%) | P value | Eptifibatide (n=384) | Abciximab (n=100) | Standardized difference (%) | P value | |

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age (years) | 64.63 ± 11.73 | 64.18 ± 11.46 | −3.8% | 0.73 | 64.22 | 64.49 | 2.3% | 0.85 |

| Male | 55.5% | 53.0% | 5.0% | 0.66 | 49.0% | 53.0% | −8.0% | 0.57 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 30.5 | 30.7 | 1.6% | 0.89 | 30.1 | 30.7 | 5.5% | 0.74 |

| White race | 66.7% | 45.0% | −45.3% | < 0.001 | 48.8% | 48.8% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Black or African American race | 30.5% | 48.0% | 37.3% | 0.001 | 47.8% | 45.6% | −4.6% | 0.44 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Current/recent smoker (within 1 year) | 20.3% | 18.0% | −5.8% | 0.61 | 19.2% | 21.5% | 5.7% | 0.67 |

| Hypertension | 95.1% | 97.0% | 9.3% | 0.41 | 97.9% | 96.1% | −8.6% | 0.42 |

| Dyslipidemia | 85.4% | 81.0% | −12.2% | 0.28 | 82.1% | 86.7% | 12.7% | 0.37 |

| Family history of premature CAD | 15.4% | 10.0% | −15.3% | 0.17 | 13.2% | 11.4% | −5.0% | 0.69 |

| Prior MI | 36.5% | 52.0% | 32.0% | 0.005 | 48.8% | 47.9% | −2.0% | 0.88 |

| Prior heart failure | 45.3% | 52.0% | 13.4% | 0.23 | 48.3% | 51.1% | 5.7% | 0.68 |

| Prior valve surgery/procedure | 1.6% | 4.0% | 17.1% | 0.13 | 2.2% | 4.2% | 14.2% | 0.39 |

| Prior PCI | 40.6% | 50.0% | 19.0% | 0.092 | 44.9% | 48.6% | 7.3% | 0.57 |

| Prior CABG | 16.1% | 25.0% | 23.1% | 0.040 | 22.0% | 22.0% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 25.0% | 29.0% | 9.1% | 0.42 | 30.2% | 27.5% | −6.1% | 0.67 |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 28.1% | 35.0% | 15.1% | 0.18 | 32.5% | 30.7% | −4.1% | 0.76 |

| Chronic lung disease | 25.3% | 30.0% | 10.8% | 0.34 | 29.0% | 29.2% | 0.5% | 0.97 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 68.2% | 73.0% | 10.3% | 0.36 | 73.3% | 72.9% | −1.0% | 0.94 |

| Heart failure within 2 weeks | 26.0% | 35.0% | 20.0% | 0.076 | 27.5% | 31.0% | 7.8% | 0.56 |

| Cardiomyopathy or left ventricular systolic dysfunction | 17.4% | 23.0% | 14.3% | 0.20 | 18.3% | 22.1% | 9.8% | 0.45 |

| Cardiogenic shock within 24 hours | 3.9% | 7.0% | 14.8% | 0.19 | 1.5% | 0.9% | −2.9% | 0.48 |

| Cardiac arrest within 24 hours | 2.3% | 2.0% | −2.3% | 0.84 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Pre-PCI left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | 48.0 ± 12.9 | 46.4 ± 13.0 | −12.2% | 0.28 | 47.8 | 47.5 | −1.9% | 0.87 |

| Pre-procedure hemoglobin (g/dL) | 11.3 ± 2.1 | 10.7 ± 1.6 | −31.4% | < 0.001 | 11.0 | 10.8 | −8.1% | 0.47 |

| CAD Presentation | ||||||||

| No symptom, no angina | 7.3% | 4.0% | −13.2% | 0.24 | 4.5% | 4.5% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Symptom unlikely to be ischemic | 1.3% | 3.0% | 13.3% | 0.25 | 1.2% | 1.2% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Stable angina | 9.4% | 8.0% | −4.8% | 0.67 | 10.1% | 10.1% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Unstable angina | 31.0% | 28.0% | −6.5% | 0.56 | 30.5% | 30.5% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Non-STEMI | 32.0% | 42.0% | 21.1% | 0.061 | 40.6% | 40.6% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| STEMI or equivalent | 19.0% | 15.0% | −10.4% | 0.36 | 13.1% | 13.1% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Pre- & Intra-procedural Antiplatelet therapy | ||||||||

| Clopidogrel | 75.8% | 71.0% | −10.8% | 0.33 | 79.2% | 74.5% | 11.1% | 0.42 |

| Prasugrel | 10.4% | 9.0% | −4.8% | 0.68 | 8.9% | 6.4% | 9.5% | 0.50 |

| Ticagrelor1 | 4.2% | 4.0% | −0.8% | 0.94 | 4.0% | 3.3% | 3.7% | 0.80 |

| Aspirin | 90.6% | 97.0% | 26.7% | 0.037 | 87.6% | 97.8% | −39.8% | 0.008 |

| Procedural Characteristics | ||||||||

| IABP | 4.2% | 6.0% | 8.8% | 0.43 | 1.8% | 1.8% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Other mechanical ventricular support | 1.8% | 4.0% | 14.6% | 0.19 | 1.2% | 1.2% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Femoral artery access site | 88.5% | 88.0% | −1.7% | 0.88 | 89.1% | 86.7% | −7.3% | 0.58 |

| Radial artery access site | 11.5% | 12.0% | 1.7% | 0.88 | 10.9% | 13.3% | 7.3% | 0.58 |

| Cardiogenic shock at start of PCI | 4.2% | 6.0% | 8.8% | 0.43 | 1.2% | 2.1% | 4.4% | 0.32 |

| PCI Indication | ||||||||

| Immediate PCI for STEMI | 17.4% | 12.0% | −14.7% | 0.19 | 12.7% | 12.1% | −1.4% | 0.67 |

| PCI for STEMI (Unstable, >12 hours from symptom onset) | 1.3% | 0.0% | −12.9% | 0.25 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| PCI for STEMI (Stable, >12 hours from symptom onset) | 1.0% | 2.0% | 8.6% | 0.44 | 0.4% | 0.9% | 4.7% | 0.67 |

| PCI for STEMI (Stable after successful full-dose thrombolysis) | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | <0.001 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | <0.001 |

| Rescue PCI for STEMI (after failed full-dose thrombolytic) | 0.0% | 1.0% | 22.1% | 0.050 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| PCI for high risk Non-STEMI or unstable angina | 53.9% | 65.0% | 22.4% | 0.047 | 63.3% | 66.5% | 6.4% | 0.28 |

| Staged PCI | 0.8% | 0.0% | −9.9% | 0.38 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | >0.99 |

| Other | 25.5% | 20.0% | −12.8% | 0.25 | 23.6% | 20.4% | −7.4% | 0.28 |

Data are presented as percentages (%) or means ± standard deviations where appropriate.

Data on ticagrelor administration was collected beginning on January 1, 2013.

Abbreviations: CAD=coronary artery disease; MI=myocardial infarction; PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention; CABG=coronary artery bypass grafting; STEMI=ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; IABP=intra-aortic balloon pump.

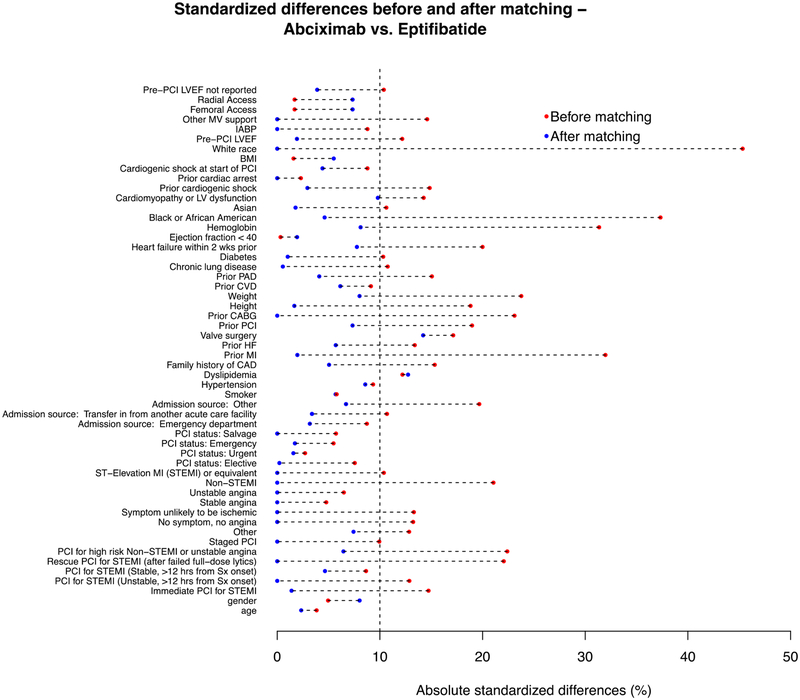

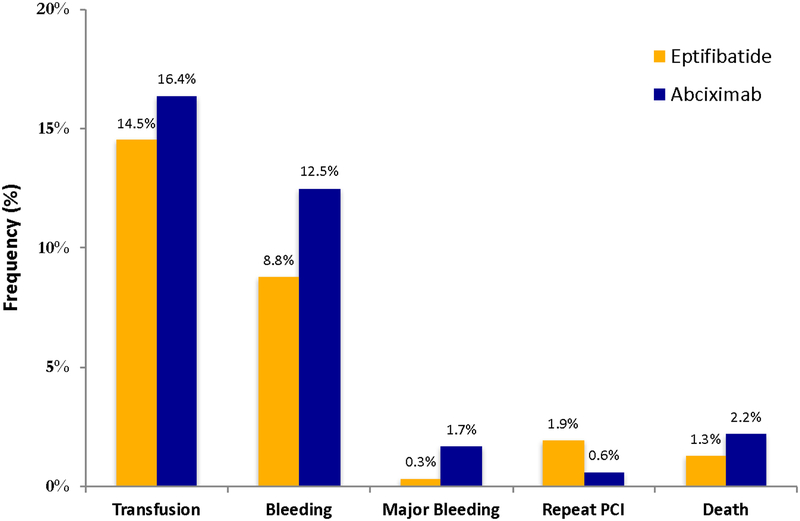

Outcomes

After optimal full matching, the ASDs were <10% for most matched variables (Figure 2) indicating globally similar baseline characteristics within matched strata (Table 2). Of note, the pre-procedural rate of clopidogrel, prasugrel, and ticagrelor administration was 79.2%, 8.9%, and 4.0% for patients receiving eptifibatide and 74.5%, 6.4%, and 3.3% for patients receiving abciximab, respectively (Table 2). There were no significant differences in the adjusted rates and odds of in-hospital outcomes between patients receiving eptifibatide compared with abciximab, respectively: need for transfusion (14.5% vs. 16.4%; aOR: 1.15; 95% CI: 0.55 – 2.40; P=0.70), bleeding (8.8% vs. 12.5%; aOR: 1.47; 95% CI: 0.64 – 3.40; P=0.36), major bleeding (0.3% vs. 1.7%; aOR: 4.68; 95% CI: 0.42 – 52.3; P=0.21), repeat PCI (1.9% vs. 0.6%; aOR: 0.38; 95% CI: 0.03 – 4.23; P=0.43), and death (1.3% vs. 2.2%; aOR: 1.53; 95% CI: 0.26 – 9.05; P=0.64) (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Plot of absolute standardized differences before and after matching.

Absolute standardized differences before and after matching in dialysis patients receiving eptifibatide compared to abciximab.

Abbreviations: CABG = coronary artery bypass grafting; CAD = coronary artery disease; CVD = cerebrovascular disease; HF = heart failure; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; MI = myocardial infarction; PAD = peripheral artery disease; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; STEMI = ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; Sx = symptoms.

Figure 3: Adjusted event rates of in-hospital outcomes in the matched cohort.

Bar graph demonstrating in-hospital outcome rates prior to matching among dialysis patients receiving eptifibatide compared with abciximab. All comparisons are non-significant (P >0.20 for all).

Abbreviations: PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention

Of the 384 patients who received eptifibatide, 224 (58.3%) received the medication post-procedurally as well as intra-procedurally whereas the remainder only received it intra-procedurally. In an unadjusted analysis, of the 224 patients who received eptifibatide in the intra- and post-procedural period 13 (5.8%) patients died, whereas only 4 of the 140 patients (2.5%) who received eptifibatide only during the procedure died during the hospitalization. Among the patients treated with abciximab, there were 4 deaths among patients treated with abciximab intra-procedurally and post-procedurally (n/N = 4/61; 6.6%), and 4 deaths among patients treated with abciximab only during the procedure (n/N = 4/39; 10.2%). The small number of patients in each group limited our ability to further investigate the effect of post-procedural GPI administration on outcomes.

Discussion

Using a large regional registry of patients undergoing PCI, we evaluated the safety of two commonly used GPIs, abciximab and eptifibatide, in dialysis patients undergoing PCI. Our study has three major findings. First, despite being contraindicated in dialysis, eptifibatide was used approximately 3.5 times more often than abciximab. Second, after propensity matching there were no significant differences in important in-hospital outcomes between the two drugs. Third, the frequency of GPI administration among dialysis patients was generally low; however, the rates of bleeding in this select population were high.

The use of GPIs around the time of PCI has been shown to reduce ischemic complications when added to UFH, although often at the expense of increased bleeding complications.13, 21, 22 Therefore, clinical practice guidelines recommend carefully considering GPI administration in populations at a high risk of bleeding events, like patients with kidney disease.18 Nevertheless, in a landmark paper, Tsai et al. discovered that nearly a quarter of patients on dialysis undergoing PCI were treated with a contraindicated medication such as eptifibatide.9 Despite this highly publicized and alarming statistic, we found that eptifibatide continues to be the most frequently prescribed GPI among dialysis patients undergoing PCI.

The reasons why eptifibatide continues to be used when contraindicated in dialysis remains unclear, though we speculate that many factors may play a role. First, eptifibatide is less expensive than abciximab which may potentially drive the increased utilization of eptifibatide.23 Furthermore, eptifibatide may be more readily available for emergent administration in the catheterization lab. Second, physicians may not be aware of the contraindications to eptifibatide. If this is the case, clinically useful electronic medical records should play an important role in reducing this type of error.

The benefit of GPIs in the management of coronary artery disease was demonstrated through a series of large randomized controlled trials which found a 33% reduction in the risk of death, nonfatal MI, or urgent revascularization at 30 days among patients undergoing PCI.24 These initial trials primarily compared GPIs to placebo. There has been only one trial directly comparing two GPIs head-to-head. The TARGET trial was a multicenter evaluation of tirofiban versus abciximab among patients undergoing PCI with the intent to perform stenting.25 The primary endpoint was a composite of death, nonfatal MI, or urgent target-vessel revascularization at 30 days. The investigators discovered a higher rate of the primary endpoint among patients treated with tirofiban compared with abxicimab (7.6% vs. 6.0%; hazard ratio = 1.26; 95% CI: 1.01 – 1.57; P=0.038). However, there was a higher rate of Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) minor bleeding among patients treated with abciximab compared with tirofiban (4.3% vs. 2.8%; P<0.001), thus demonstrating the careful balance between ischemic and bleeding complications with these drugs.25 The current study also demonstrates the balance between these two complications. Patients treated with eptifibatide had lower adjusted rates of bleeding complications but a higher rate of repeat PCI (i.e. ischemic complication) compared with abciximab; however, these differences were not statistically significant. To date, there have been no trials directly comparing eptifibatide with either abciximab or tirofiban.

Although we were unable to determine the reasons for the continued use of eptifibatide in this high-risk population, it is important to note that we did not find significant differences in the rates of in-hospital bleeding, transfusion, or mortality among dialysis patients who received eptifibatide compared with abciximab.9, 10 A similar finding was noted in a recent study by Barnes et al. where they found no significant differences in the rates of peri-procedural bleeding and 30-day mortality among dialysis patients who received eptifibatide during PCI at a Veterans Affairs hospital, although the confidence intervals around the point estimates were wide.10 Also of note, although Tsai et al. demonstrated an increased risk of bleeding among dialysis patients who were treated with a contraindicated medication, eptifibatide use was associated with a significantly increased risk of in-hospital bleeding only in the subgroup of patients presenting with ACS.9 In an unadjusted analysis, we discovered a higher frequency of in-hospital death among patients who were treated with eptifibatide in the intra-procedural and post-procedural time periods compared with patients who only received intra-procedural eptifibatide. It is possible that continued eptifibatide treatment after the procedure may result in accumulation of the drug in dialysis patients leading to a higher rate of adverse events. Of course, such a finding is confounded by the fact that procedural complications or other patient characteristics may be associated with post-procedural GPI use. Due to the limited number of patients in our study, we did not perform any subgroup analyses out of concern for type I errors resulting from multiple testing.

Limitations

There are several important limitations that deserve specific mention. First, as previously noted, we were unable to determine the rationale for GPI administration which may have resulted in inadequate matching. For example, a modest proportion of patients may have received eptifibatide in a provisional fashion due to unmeasured circumstances that occurred during PCI (i.e. extreme thrombus burden, ongoing ischemia, etc.). These factors may represent confounding variables associated with the non-random administration of these drugs. Although we attempted to account for the non-random administration of the studied medications through propensity-matching techniques, due to the retrospective nature of this study, we were unable to account for all potential confounders. Second, wide confidence intervals around the point estimates for the adjusted odds ratios for each outcome may be related to our small sample size and limited power to detect a true association. Nevertheless, the direction of the point estimates suggests increased harm with abciximab, not eptifibatide. Third, all hospitals participating in this registry are actively engaged in statewide collaborative quality improvement initiatives. As such, these findings may not be generalizable to hospitals that do not participate in such initiatives.26 Lastly, we did not collect data on medication dosages or the timing of medication administration relative to the patient’s subsequent dialysis session. This may have an important impact on the safety and efficacy of these drugs as prior research has demonstrated that medications are frequently dosed incorrectly in patients with renal insufficiency.2, 11, 27 Furthermore, prior research suggests that hemodialysis can effectively reverse the antithrombotic effects of eptifibatide, potentially affecting the decision to use the drug and its impact on clinical outcomes.14, 28, 29

Conclusion

Although eptifibatide is contraindicated in patients on dialysis, it was used approximately 3.5 times more often than abciximab during PCI. However, in a propensity-matched analysis, we discovered similar safety outcomes between eptifibatide and abciximab among dialysis patients who underwent PCI. These findings suggest the need for further investigation into the reasons why eptifibatide continues to be used in this population and why there are no significant differences in outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors are indebted to all the study coordinators, investigators, and patients who participated in the BMC2 registry.

Funding:

Dr. Sukul is supported by the National Institutes of Health T32 postdoctoral research training grant (T32-HL007853). This work was supported by the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan and Blue Care Network as part of the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Value Partnerships program. The funding source supported data collection at each site and funded the data-coordinating center but had no role in study concept, interpretation of findings, or in the preparation, final approval or decision to submit the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement:

Hitinder S. Gurm receives research funding from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan, the National Institutes of Health and is a consultant for Osprey Medical. None of the authors have any conflicts directly relevant to this study.

ABBREVIATIONS

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- GPI

glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor

- UFH

unfractionated heparin

- BMC2

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium

- NCDR

National Cardiovascular Data Registry

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- STEMI

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- NSTEMI

non-ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

- IABP

intra-aortic balloon pump

- ASD

absolute standardized difference

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- TIMI

Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: Although Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM) and BMC2 work collaboratively, the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinions, beliefs and viewpoints of BCBSM or any of its employees.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capodanno D, Angiolillo DJ. Antithrombotic therapy in patients with chronic kidney disease. Circulation. 2012;125:2649–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaw D, Malhotra D. Platelet dysfunction and end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2006;19:317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chew DP, Lincoff AM, Gurm H, et al. Bivalirudin versus heparin and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition among patients with renal impairment undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (a subanalysis of the REPLACE-2 trial). The American journal of cardiology. 2005;95:581–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehran R, Nikolsky E, Lansky AJ, et al. Impact of chronic kidney disease on early (30-day) and late (1-year) outcomes of patients with acute coronary syndromes treated with alternative antithrombotic treatment strategies: an ACUITY (Acute Catheterization and Urgent Intervention Triage strategY) substudy. JACC Cardiovascular interventions. 2009;2:748–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Best PJ, Lennon R, Ting HH, et al. The impact of renal insufficiency on clinical outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2002;39:1113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Casserly LF, Dember LM. Thrombosis in end-stage renal disease. Semin Dial. 2003;16:245–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coca SG, Krumholz HM, Garg AX, Parikh CR. Underrepresentation of renal disease in randomized controlled trials of cardiovascular disease. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;296:1377–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai TT, Maddox TM, Roe MT, et al. Contraindicated medication use in dialysis patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;302:2458–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barnes GD, Stanislawski MA, Liu W, et al. Use of Contraindicated Antiplatelet Medications in the Setting of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: Insights From the Veterans Affairs Clinical Assessment, Reporting, and Tracking Program. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Melloni C, James SK, White JA, et al. Safety and efficacy of adjusted-dose eptifibatide in patients with acute coronary syndromes and reduced renal function. American heart journal. 2011;162:884–92 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of eptifibatide on complications of percutaneous coronary intervention: IMPACT-II. Integrilin to Minimise Platelet Aggregation and Coronary Thrombosis-II. Lancet. 1997;349:1422–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Therapy EIESotPIIRwI. Novel dosing regimen of eptifibatide in planned coronary stent implantation (ESPRIT): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2000;356:2037–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Integrillin(R) (eptifibatide) Full Prescribing Information.

- 15.Kline-Rogers E, Share D, Bondie D, et al. Development of a multicenter interventional cardiology database: the Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan Cardiovascular Consortium (BMC2) experience. Journal of interventional cardiology. 2002;15:387–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moscucci M, Rogers EK, Montoye C, et al. Association of a continuous quality improvement initiative with practice and outcome variations of contemporary percutaneous coronary interventions. Circulation. 2006;113:814–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.NCDR CathPCI Registry v4.4 Coder’s Data Dictionary.

- 18.Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, et al. 2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011;58:e44–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hansen BB, Klopfer SO. Optimal full matching and related designs via network flows. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2006;15:609–27. [Google Scholar]

- 20.R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Stone GW, et al. Abciximab as adjunctive therapy to reperfusion in acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2005;293:1759–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kastrati A, Mehilli J, Neumann FJ, et al. Abciximab in patients with acute coronary syndromes undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention after clopidogrel pretreatment: the ISAR-REACT 2 randomized trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:1531–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gurm HS, Smith DE, Collins JS, et al. The relative safety and efficacy of abciximab and eptifibatide in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: insights from a large regional registry of contemporary percutaneous coronary intervention. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2008;51:529–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sabatine MS, Jang IK. The use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 2000;109:224–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Topol EJ, Moliterno DJ, Herrmann HC, et al. Comparison of two platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, tirofiban and abciximab, for the prevention of ischemic events with percutaneous coronary revascularization. The New England journal of medicine. 2001;344:1888–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Share DA, Campbell DA, Birkmeyer N, et al. How a regional collaborative of hospitals and physicians in Michigan cut costs and improved the quality of care. Health affairs. 2011;30:636–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Long CL, Raebel MA, Price DW, Magid DJ. Compliance with dosing guidelines in patients with chronic kidney disease. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38:853–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudson JQ, McNeely EB, Green CA, Jennings LK. Assessment of eptifibatide clearance by hemodialysis using an in vitro system. Blood Purif. 2010;30:266–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sperling RT, Pinto DS, Ho KK, Carrozza JP Jr., Platelet glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibition with eptifibatide: prolongation of inhibition of aggregation in acute renal failure and reversal with hemodialysis. Catheterization and cardiovascular interventions : official journal of the Society for Cardiac Angiography & Interventions. 2003;59:459–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.