Abstract

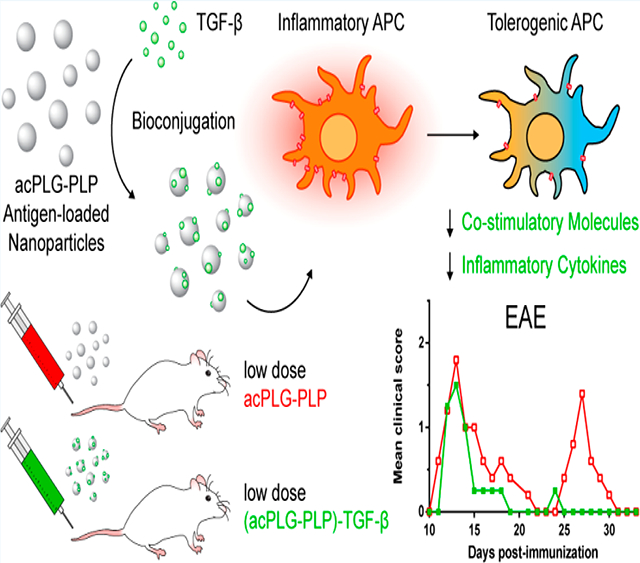

Current strategies for treating autoimmunity involve the administration of broad-acting immunosuppressive agents that impair healthy immunity. Intravenous (i.v.) administration of poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoparticles (NPs) containing disease-relevant antigens (Ag-NPs) have demonstrated antigen (Ag)-specific immune tolerance in models of autoimmunity. However, subcutaneous (s.c.) delivery of Ag-NPs has not been effective. This investigation tested the hypothesis that codelivery of the immunomodulatory cytokine, transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β), on Ag-NPs would modulate the immune response to Ag-NPs and improve the efficiency of tolerance induction. TGF-β was coupled to the surface of Ag-NPs such that the loadings of Ag and TGF-β were independently tunable. The particles demonstrated bioactive delivery of Ag and TGF-β in vitro by reducing the inflammatory phenotype of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells and inducing regulatory T cells in a coculture system. Using an in vivo mouse model for multiple sclerosis, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, TGF-β codelivery on Ag-NPs resulted in improved efficacy at lower doses by i.v. administration and significantly reduced disease severity by s.c. administration. This study demonstrates that the codelivery of immunomodulatory cytokines on Ag-NPs may enhance the efficacy of Ag-specific tolerance therapies by programming Ag presenting cells for more efficient tolerance induction.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Millions of Americans are affected by an autoimmune disorder, and the currently available treatments address the clinical symptoms but are not considered curative. Autoimmunity arises from abnormal immune recognition of endogenous antigens (Ags) resulting in the self-destruction of the body’s vital tissues.1,2 Clinically available treatment strategies attempt to mitigate symptoms using immunosuppressive molecules and biologics that nonspecifically block entire immune pathways which can leave individuals susceptible to opportunistic infections and neoplastic growths.3–5 Rather than nonspecifically blocking immune responses, strategies that can block responses to specific Ags have the potential to address the pathology of disease while leaving protective immunity intact.

Peptide- and protein-loaded nanoparticles (NPs) have been developed as strategies to induce Ag-specific immune tolerance.1,2 NPs comprising biodegradable polymers have been formulated with Ag encapsulated, surface-bound, or conjugated to the bulk polymer of the NP. These various Ag-NPs platforms have demonstrated transplantation tolerance and abrogation of Th1/17- and Th2-mediated hypersensitivity.6–15 Strategies that employ Ag-NPs are frequently administered intravenously (i.v.), where they distribute to the liver and spleen and are cleared by Ag presenting cells (APCs) in a fashion that resembles the body’s natural clearance of apoptotic cells. The negative charge of the particles has been associated with increased internalization by macrophages resulting in Ag presentation and anti-inflammatory signaling by IL-10 and regulatory T cell (Treg) production.6,16 Although Ag-NPs have not been evaluated for toxicity, dose escalation studies have demonstrated toxicity of similar polyester NPs at high doses, which motivates the design of Ag-NPs that induce tolerance efficiently at lower doses.17,18 Additionally, despite advances in i.v.-induced NP tolerance, Ag-specific tolerance by subcutaneously (s.c.)-delivered NPs has not yet been realized without the use of other anti-inflammatory mediators such as IL-10, antisense oligonucleotides, or the immunosuppressive agent rapamycin.7,19,20 As a s.c. administered therapy, Ag-NP-induced tolerance could be more accessible to patients outside of the hospital setting, increasing the societal impact of this treatment. Overcoming the immunological barriers with s.c. administration motivates the use of anti-inflammatory cytokines in NP immune therapy.

Transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β) is a pleiotropic cytokine that reduces inflammation, maintains peripheral tolerance, and, importantly, has been shown to impart and maintain protective tolerance in models of autoimmunity.21 Previous studies have shown that TGF-β injections can delay and prevent disease onset in relapsing-remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), a mouse model of multiple sclerosis (MS). Repeated s.c. injections of TGF-β reduced the occurrence and severity of EAE in mice adoptively transferred with active myelin basic protein (MBP)-specific T cells.22 When administered i.v., TGF-β decreased the severity of EAE symptoms in new and ongoing disease.23 Mechanistically, mice lacking functional TGF-β receptor II (TGF-βRII) on their dendritic cells showed increased severity of EAE disease symptoms, and spontaneously developed EAE symptoms when crossed with mice containing only myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG)-specific T cell receptors.24 Thus, TGF-β signaling plays a vital role in preventing the pathological onset of autoimmune inflammation. However, due to its pleiotropic effects, TGF-β monotherapy would have the same disadvantages as immunosuppressive agents. Therefore, the therapeutic use of TGF-β should be in the setting of disease-relevant Ag to skew the context of Ag presentation toward one that promotes Ag-specific tolerance.

This investigation tested the hypothesis that codelivery of surface-coupled TGF-β with encapsulated autoAg using a single poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (PLG) NP could modulate and enhance Ag-specific immune responses. An in vitro coculture system of bone marrow-derived dendritic cells (BMDCs) and naïve T cells was used to evaluate the bioactivity of Ag and TGF-β codelivered by NPs. The immunomodulatory effects of TGF-β-coupled NPs on mature and immature BMDCs were determined by analyzing surface costimulatory markers and inflammatory cytokine production. The in vivo Treg frequency and number were measured following injection of particles into OT-II mice that expressed OVA323–339-restricted T cell receptors. Finally, the ability of surface-bound TGF-β to enhance the tolerogenicity of Ag-NPs was evaluated using the EAE mouse model in the context of i.v. and s.c. administration routes.

RESULTS

Bioactivity of TGF-β-Coupled PLG Nanoparticles.

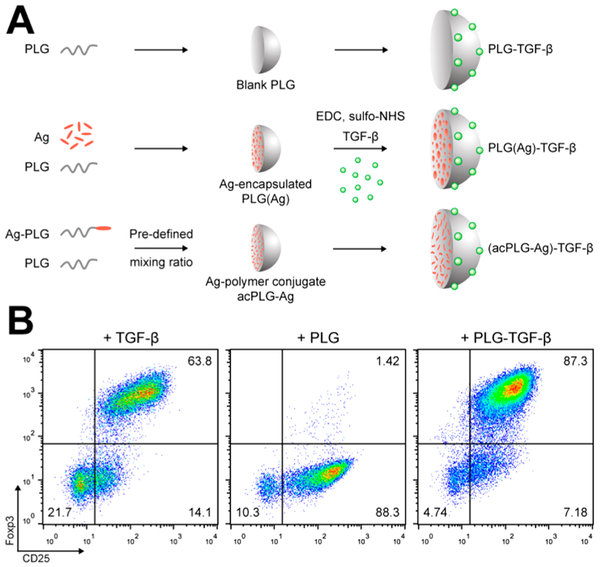

TGF-β was chemically coupled to the surface of PLG NPs (PLG-TGF-β NPs) using carbodiimide chemistry (Figure 1A).25 The bioactivity of NP-bound TGF-β was determined in vitro by its ability to differentiate naïve CD4+CD25−Foxp3− T cells into CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs. In this Treg induction assay, naïve CD4+CD25− T cells stimulated with anti-CD3, anti-CD28, and IL-2 alone resulted in an upregulated expression of CD25 but not Foxp3. The addition of soluble TGF-β resulted in a significant differentiation and expansion of CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ T cells, and delivery of surface-bound TGF-β by PLG-TGF-β NPs achieved the same high level of Treg differentiation as soluble TGF-β (Figure 1B). This result demonstrated that TGF-β can be delivered on NP surfaces with sufficient quantity and bioactivity to elicit robust immunological and tolerance-enhancing responses.

Figure 1.

Surface-coupled TGF-β is bioactively delivered by PLG nanoparticles. (A) Schematic depiction of the NP production and TGF-β conjugation procedure used to create the NPs in this study. TGF-β was conjugated to blank PLG, Ag-encapsulated, and Ag-polymer conjugate NPs. (B) Naïve CD4+CD25− T cells were cultured in anti-CD3-coated plates for 4 days in the presence of 2 μg/mL anti-CD28, 10 ng/mL IL-2, and 2 ng/mL of soluble TGF-β, blank PLG NPs, or 300 μg/mL of PLG-TGF-β NPs (166 ng TGF-β/mg). T cells were characterized by flow cytometry for CD25 and intracellular Foxp3.

Antigen and TGF-β Bioactive Codelivery by Nanoparticles.

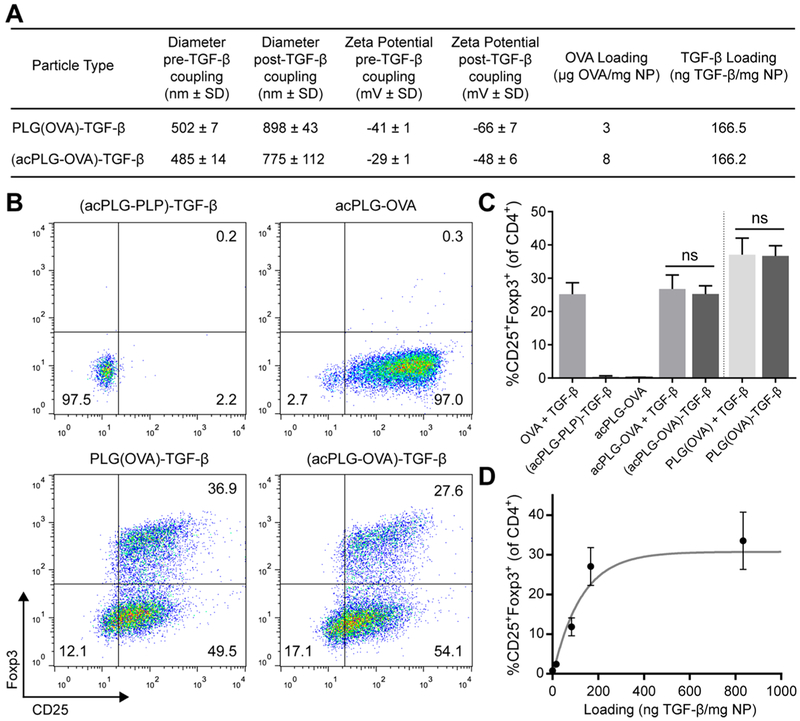

NP-coupled TGF-β and NP-associated Ag were subsequently evaluated for bioactivity in a single NP for its ability to promote tolerogenic Ag-specific responses. Two Ag-NP platforms were evaluated for TGF-β delivery: Ag-encapsulated (PLG(Ag)) NPs and Ag-polymer conjugate (acPLG) NPs (Figure 1A). The PLG(Ag) particles encapsulated Ag using a double emulsion approach, whereas the acPLG particles incorporate Ag by admixing unmodified PLG with a precise quantity of Ag-PLG polymer conjugates.10,11 TGF-β was conjugated to OVA323–339 (OVA) peptide-loaded NPs and an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) determined that the loading of TGF-β on PLG(OVA)-TGF-β NPs and (acPLG-OVA)-TGF-β was 166 ng TGF-β per mg of NP. Conjugation of TGF-β to the NP resulted in an increase in NP size and a decrease in the zeta potential (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

TGF-β and antigen are bioactively codelivered by PLG particles to induce antigen-specific Tregs. (A) Characterization of Ag-NPs before and after TGF-β conjugation. Antigen-loaded NPs were prepared by encapsulating OVA peptide [PLG(OVA) NPs] or by incorporating PLG-Ag conjugates with unmodified PLG (acPLG NPs). (B–D) BMDCs were treated for 3 h with 300 μg/mL of Ag-NPs. After 3 h, media was exchanged to remove excess particles. The BMDCs were then cocultured for 4 days with naïve OT-II CD4+CD25− T cells at a 1:1 ratio. Cells that were not treated with NPs received 100 ng/mL of OVA and 2 ng/mL of TGF-β. (B) Representative plots of flow cytometry data gated on live CD4+ T cells. (C) Treg induction was compared between solubly derived TGF-β and NP-bound TGF-β codelivered with PLG(OVA) NPs (3 μg OVA/mg) and acPLG-OVA NPs (2 μg OVA/mg). (D) Treg induction was evaluated with titrated amounts of TGF-β conjugated to acPLG-OVA NPs (OVA loading constant at 8 μg/mg). Statistical differences were determined using a two-tailed unpaired t test. Error bars indicate SD.

The bioactive codelivery of Ag and TGF-β by PLG NPs was evaluated in a coculture of BMDCs and OVA-specific OT-II T cells. In this assay, the delivery of OVA resulted in Ag presentation by BMDCs and T cell activation as measured by the expression of CD25 on nearly all T cells (Figure 2B). The administration of soluble TGF-β with OVA resulted in a CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg induction frequency of 25% (Figure 2C). Codelivery of TGF-β and OVA by PLG(OVA)-TGF-β and (acPLG-OVA)-TGF-β particles both resulted in Treg frequencies comparable to treatment with soluble OVA and TGF-β, or soluble TGF-β administered with Ag-only NPs. Importantly, codelivery of TGF-β with irrelevant peptide, PLP139–151 (PLP), resulted in no T cell stimulation or Treg differentiation as indicated by the absence of CD25 and Foxp3 expression by T cells (Figure 2B,C).

The effective range of TGF-β loading on Ag-NPs was determined by titrating the amount of TGF-β conjugated to acPLG-OVA particles followed by measuring the degree of Treg differentiation in the BMDC:T cell coculture assay. At a fixed loading of 8 μg OVA per mg of acPLG-OVA NP, the Treg induction efficiency of (acPLG-OVA)-TGF-β NPs increased with the TGF-β loading, reaching a maximum Treg induction efficiency of 27% with a TGF-β coupling of 166 ng TGF-β/mg NP with no further enhancement up to 800 ng TGF-β/mg NP (Figure 2D). Collectively, these data demonstrate that Ag and TGF-β were bioactively codelivered by PLG(Ag)-TGF-β and (acPLG-Ag)-TGF-β NPs and that the resulting in vitro Treg induction is Ag-specific.

PLG Nanoparticles Downregulate Dendritic Cell Costimulatory Molecules and Reduce Inflammatory Cytokine Secretion.

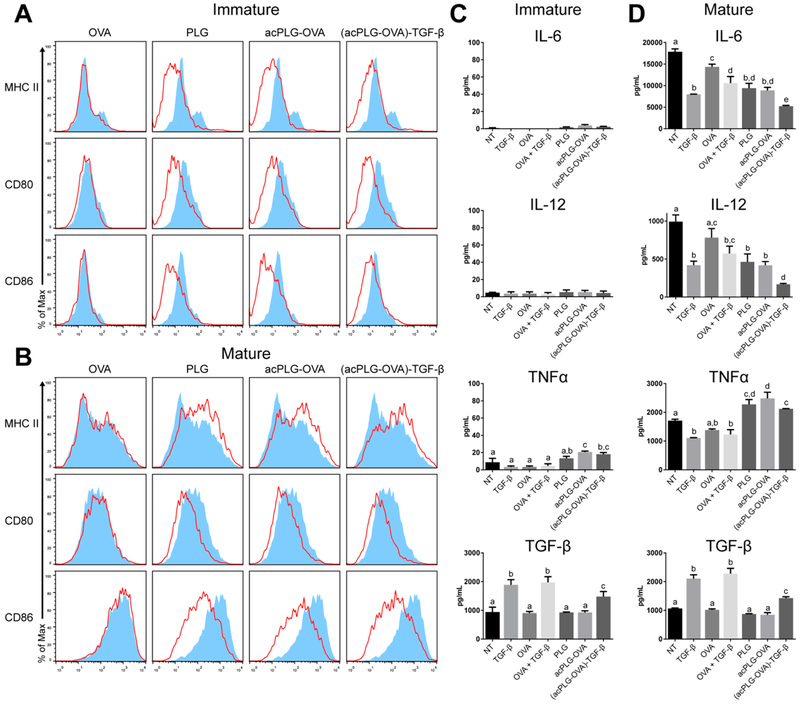

BMDCs were used to investigate the effect of TGF-β-coupled NPs on APC phenotype, as dendritic cells (DCs) are specialized to initiate immune responses by presenting Ag and costimulatory signals to T cells. BMDC costimulatory molecules and cytokines were assessed for phenotypic changes following in vitro incubation with NPs. Immature BMDCs treated with NPs [PLG, acPLG-OVA, or (acPLG-OVA)-TGF-β] exhibited a downregulation of MHC II and costimulatory markers CD80 and CD86 regardless of Ag or TGF-β delivery (Figure 3A). NP-induced downregulation of CD80 and CD86 was also observed in BMDCs matured with interferon gamma (IFNγ) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), but MHC II expression increased in response to NPs administered in the presence of maturation signals (Figure 3B). Analysis of the secreted cytokines revealed that mature BMDCs produced about 2-fold less IL-6 and IL-12 in the presence of soluble TGF-β, PLG NPs, or acPLG-OVA NPs. This effect was augmented by TGF-β delivery on NPs, which resulted in a 3-and 6-fold reduction in IL-6 and IL-12 production, respectively (Figure 3D). In contrast, treatment with NPs increased the production of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), and NP-associated TGF-β did not have an effect on this production (Figure 3C,D).

Figure 3.

NP treatment decreases BMDC costimulatory molecule expression and cytokine secretion. BMDCs were treated with soluble OVA or with NPs for 3 h. Excess NPs were washed away and cells were incubated for 4 days. (A and C) BMDCs were unstimulated (immature) or (B and D) stimulated (mature) with 10 ng/mL of IFNγ and 10 ng/mL LPS after 3 h NP treatment. (A and B) BMDCs were evaluated by flow cytometry on day 4. Histograms show live cell surface molecule expression with red line histograms representing the indicated treatment and blue filled histograms representing untreated BMDCs. (C and D) The cytokines present in the BMDC media on day 4 were evaluated by ELISA. Statistical differences were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. Within data subsets, no significant difference was observed between conditions labeled with matching letters (p > 0.05). Error bars indicate SD.

Soluble TGF-β was measured to investigate whether the anti-inflammatory responses were achieved by the immobilized TGF-β, or through TGF-β that may have been released from the particle. The quantity of soluble TGF-β contributed by (acPLG-OVA)-TGF-β NPs was intermediate between TGF-β levels in the serum-supplemented media and media supplemented with 2 ng/mL of soluble TGF-β. This low level of TGF-β released from the particle is insufficient to affect the changes observed in the BMDC response, and suggests that the reduction in inflammatory cytokines by incubation with TGF-β-coupled particles is due to particle-bound TGF-β rather than an increase in the soluble presence of TGF-β (Figure 3C,D). IL-10 was below the limit of detection in all conditions tested (data not shown).

Ag-NPs Affect Changes in the T Cell Compartment.

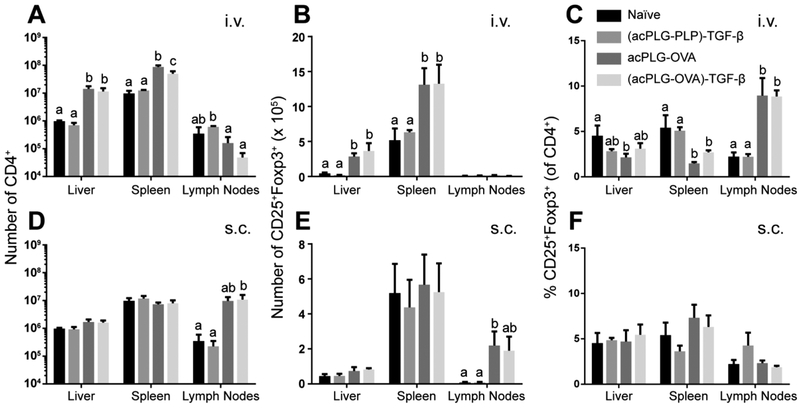

The in vivo effect of TGF-β-coupled particles on Ag-specific T cell responses was investigated using OVA-loaded NPs in the OT-II mouse. Mice were injected with 1.25 mg of Ag-NPs (8 μg Ag/mg, 166 ng TGF-β/mg) i.v. or s.c. to evaluate Ag presentation by distinct delivery mechanisms. As expected, the NP route of administration determined the site of T cell expansion. In the spleen and liver, i.v. delivery of OVA-loaded NPs resulted in a 6-fold and 10-fold increase in the number of CD4+ T cells, which included an increase in the number of Tregs (2-fold and 5-fold, respectively) (Figure 4A,B). However, this increase in T cell and Treg number corresponded to a decrease in the frequency of Tregs in the spleen and liver when treated with acPLG-OVA without TGF-β (Figure 4C). No changes in the liver and spleen T cell populations were observed following s.c. NP administration (Figure 4D–F).

Figure 4.

Ag-NPs cause Ag-specific changes in T cell populations in vivo. OT-II mice were untreated or injected with 1.25 mg of NPs (8 μg Ag/mg, 166 ng TGF-β/mg). (A–C) Mice treated i.v. received a single tail vein injection. (D–F) Mice treated s.c. received 4 injections distributed over the shoulders and hind limbs. After 7 days, the livers, spleens, and pooled brachial, axillary, and inguinal lymph nodes were excised and analyzed by flow cytometry for CD4+ T cells and CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs. Statistical differences were determined by Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. Within data subsets, no significant difference was observed between conditions labeled with matching letters (p > 0.05). Error bars indicate SEM.

In the pooled axillary, brachial, and inguinal lymph nodes (LNs), the number of CD4+ T cells increased 30-fold after s.c. injection of particles containing OVA. The expansion of T cells was not associated with a change in Treg proportion, which was maintained at 2% (Figure 4F). Interestingly, the percentage of LN Tregs increased 4-fold after i.v. administration of OVA-loaded particles (Figure 4C). In general, OVA-loaded NPs caused increases in OT-II T cell and Treg numbers in the liver and spleen following i.v. administration and in the lymph nodes following s.c. administration. The T cell expansion was Ag-specific, and there was not an increase in Treg number or frequency attributed to TGF-β codelivery on the particles.

Surface Conjugation of TGF-β Improves the Tolerogenic Effect of Ag-NPs.

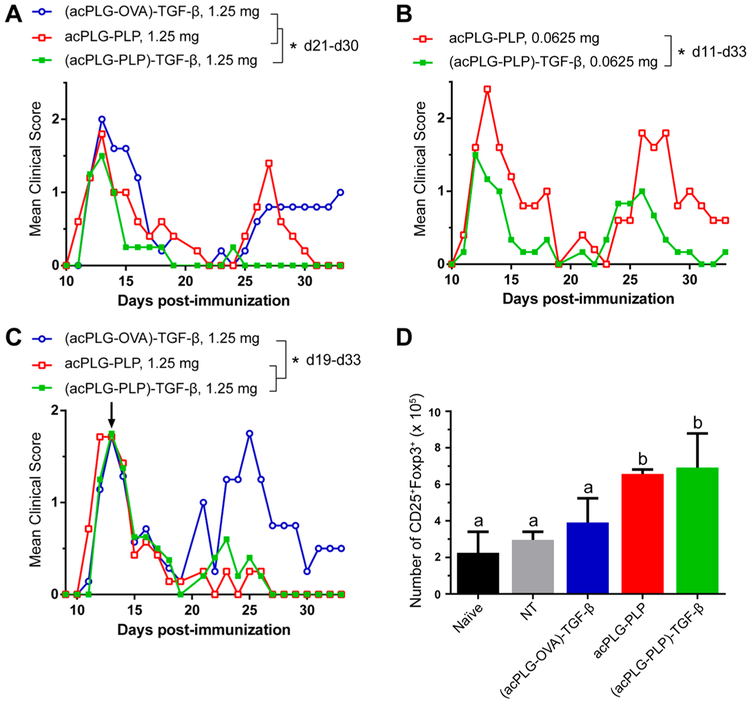

The hypothesis that functionalizing Ag-loaded NPs with TGF-β would improve the efficiency of tolerance induction was tested in the EAE model by comparing the clinical disease scores of mice treated by Ag-NPs, with and without surface-coupled TGF-β. PLG NPs loaded with only disease-relevant peptides have demonstrated robust tolerance in previous studies; therefore, TGF-β-coupled NPs were investigated in the EAE model at subtherapeutic doses to identify therapeutic contributions of the TGF-β modification.6,9–11 A single i.v. dose of 2.5 mg of acPLG–PLP (8 μg PLP/mg) was determined as the minimum requirement for suppression of EAE disease symptoms and was used as the standard for dose reduction comparisons (Figure S1). Mice were injected once with either an intermediate dose (1.25 mg, 2-fold lower) or a low dose (0.0625 mg, 40-fold lower) of Ag-NPs (8 μg Ag/mg, 166 ng TGF-β/mg) compared to the noted therapeutic dose of 2.5 mg. At the intermediate dose of 1.25 mg NPs, surface-bound TGF-β did not reduce disease scores between days 10–14 (acute disease), yet was able to mitigate relapse disease scores (days 21–30) compared to acPLG–PLP and (acPLG-OVA)-TGF-β NPs (Figure 5A). This result suggests that surface-modification with TGF-β enhances tolerance in an Ag-specific context, and does not broadly suppress the immune response to nonrelevant epitopes, respectively. No significant difference was observed between the clinical disease courses of the acPLG–PLP and (acPLG-OVA)-TGF-β conditions during this period. At the low dose of 0.0625 mg NPs, (acPLG–PLP)-TGF-β NPs significantly reduced the severity of the mean clinical score over the acute and relapse disease course compared to acPLG–PLP NPs (Figure 5B). Subsequently, mice were treated therapeutically with 1.25 mg of NPs (day 13, third day after disease onset), to identify whether the particles can attenuate the autoimmune response in a pathogenic population of activated T cells. Both TGF-β-coupled and noncoupled acPLG–PLP NPs resulted in abrogated clinical scores from days 19–33 (relapse disease) (Figure 5C). On day 19 post-immunization (6 days after NP injection), mice from each cohort (n = 3) were euthanized and the number of Tregs in their livers, spleens, and pooled lymph nodes were quantified. The number of Tregs increased in the livers of mice treated with acPLG–PLP and (acPLG–PLP)-TGF-β NPs (Figure 5D), with no change in the spleen and lymph nodes (data not shown).

Figure 5.

TGF-β codelivery improves the tolerogenic efficiency of Ag-loaded NPs in EAE model. (A,B) SJL mice were prophylactically injected i.v. with subtherapeutic doses of Ag-NPs (A, 1.25 mg or B, 0.0625 mg at 8 μg Ag/mg and 166 TGF-β/mg). After 7 days, mice were immunized with PLP/CFA on day 0 to induce EAE (n = 5). (C,D) SJL mice (n = 7) were immunized (day 0) and injected with 1.25 mg of Ag-NPs (8 μg Ag/mg, 166 ng TGF-β/mg) on day 13 (the third day of disease presentation). Six days after injection, 3 mice per cohort were euthanized and (D) the number of liver CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs was quantified using flow cytometry. Statistical differences between treatments for the indicated time periods were determined by (A and C) the Kruskal–Wallis test (one-way ANOVA nonparametric test) with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (p < 0.05) or(B) the Mann–Whitney (two-tailed nonparametric) test (p < 0.05). Statistical differences between cell numbers (D) were determined using Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test. Within data subsets, no significant difference was observed between conditions labeled with matching letters (p > 0.05). Error bars indicate SD.

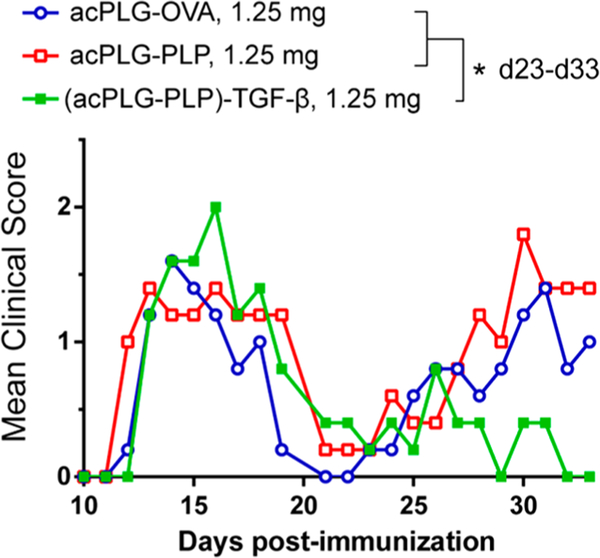

Subcutaneous Delivery of TGF-β Conjugated Ag-NPs Reduces Relapse Scores in EAE.

The local codelivery of Ag and TGF-β by NPs in the s.c. space and draining LNs was hypothesized to program a tolerogenic phenotype in the APCs thereby skewing the context of Ag presentation toward one that favors a tolerogenic outcome. Mice were injected s.c. with 1.25 mg Ag-NPs (8 μg Ag/mg) and presented similar mean clinical scores in the acute disease phase from days 11–21 post- immunization (Figure 6). In the relapsing phase of disease, from days 23–33, no difference in the clinical scores was observed between the acPLG-OVA- and acPLG–PLP-treated mice. However, mice treated s.c. with (acPLG–PLP)-TGF-β NPs (166 ng TGF-β/mg) experienced a maximum relapse score that was approximately half that of the other NP groups and exhibited a significant reduction in the severity of relapsing clinical scores from days 23–33. This decrease in EAE clinical scores resulting from TGF-β codelivery on PLP-loaded NPs suggests an immunomodulatory role for TGF-β, and supports further investigation into the codelivery of exogenous cytokines on NPs for modulating Ag-specific immune responses.

Figure 6.

Subcutaneous delivery of TGF-β-coupled Ag-NPs reduces the severity of relapse symptoms in EAE. SJL mice were injected s.c. with 1.25 mg of Ag-NPs (8 μg Ag/mg, 166 ng TGF-β/mg) 7 days before immunization with PLP/CFA to induce EAE (n = 5). Statistical differences between treatments for the indicated time periods were determined by the Kruskal–Wallis test (one-way ANOVA nonparametric test) with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Delivery of autoAgs using NPs is a promising strategy to induce Ag-specific tolerance to disease-relevant Ags without suppressing the diverse repertoire of immune cells required for maintaining protective immunity.1,6,9,11,15,26 The efficacy of Ag-NPs has previously been shown to be dependent on dose and route of administration (i.v.).9 While Ag-NPs have demonstrated the primary end point of immune tolerance, others have demonstrated toxicity by similar NPs at high doses.17,18 Therefore, to reduce the dose of Ag-NPs required to induce tolerance and to enable the use of a simpler and more clinically accessible route of administration (s.c.), this report investigated the effect of codelivered TGF-β, a pleiotropic immunomodulator, on Ag-loaded PLG NPs. Codelivery of surface-bound TGF-β on Ag-loaded PLG NPs enhanced the tolerogenic efficiency (reduced dose) and provided an enabling solution to induce tolerance through a previously unproven route of administration (s.c.) using PLG Ag-NPs.

PLG-based particles were produced with Ag and modified with TGF-β in a codelivery platform that achieves precise Ag loading and maintains bioactivity of both immune-modulating factors (Figure 2). Water-soluble cytokines, growth factors, and short peptides are commonly encapsulated using a double emulsion protocol.10,19,27 Controlling the coencapsulation of multiple factors is complicated by differences in the molecule size, pKa, and solubility of each component. These molecular variables can thermodynamically limit the control over encapsulation efficiency, loading, and desired release profile.28 Therefore, many particle systems deliver Ag and immune-modifiers in separate NPs.19,27,29 Herein, Ag was covalently attached to the polymer, particles were formed with this Ag-PLG bioconjugate, and the resulting Ag-NPs were subsequently modified with TGF-β. This approach ensures that the NP has both Ag and TGF-β, which can provide signals to program APCs toward tolerogenic phenotypes (Figure 2). Unlike encapsulation, the covalent and stepwise attachment of the Ag and TGF-β to the NP avoids uncontrolled release and minimizes off-target effects while allowing the loading of each factor to be independently tuned.11 Taken together, these NPs provide a platform for flexible, precise, and bioactive codelivery of disease-relevant peptides and immune-modifying proteins.

TGF-β-coupled Ag-NPs downregulated costimulatory molecules and secretion of Th1/Th17-associated inflammatory cytokines in vitro, using LPS and IFNγ stimulated mature BMDCs, which may reduce their potential for differentiating naïve T cells toward effector lineages (Figure 3). The decrease in the expression of surface proteins MHC II, CD80, and CD86 observed with TGF-β-coupled Ag-NPs is phenotypically similar to other strategies for inducing tolerogenic DCs such as in vitro incubation with cytokines, siRNA knockdown of CD80/CD86, and genetic modification for endogenous cytokine production.20,30,31 The decrease in CD80 and CD86 was also observed in mature BMDCs treated with Ag-NPs; however, an upregulation of MHC II was observed. Cytokine secretion also contributes to APC phenotype, with IL-12 and IL-6 being well characterized for their role in the differentiation of Th1 and Th17 T helper cells. Further, these cytokines are implicated in the pathogenesis of EAE and human MS.32,33 IL-12 signals the differentiation of IFNγ-secreting Th1 cells, and IL-6 works together with TGF-β to signal the differentiation of IL-17 secreting Th17 cells that are associated with immune-mediated demyelination in the central nervous system (CNS) of individuals with MS. As a codelivery platform, TGF-β-coupled Ag-NPs synergistically decreased both IL-12 and IL-6 production to levels significantly lower than Ag-NPs or TGF-β separately. The reduction of DC-secreted IL-12 by TGF-β-coupled NPs is in agreement with a similar result using microparticles to locally deliver soluble TGF-β.27 Collectively, the in vitro data presented suggests that BMDCs respond to (acPLG-Ag)-TGF-β NPs by providing tolerogenic signals in the three-signal hypothesis of T cell activation: (1) peptide delivery for Ag-specific TCR recognition, (2) decreased costimulatory molecules, and (3) suppressed secretion of cytokines responsible for Th1 and Th17 differentiation.34

Injection of TGF-β-coupled particles i.v. and s.c. resulted in similar attenuation of EAE disease scores (Figures 5 and 6) despite the differential organ and immune cell distribution associated with these administration routes. In both contexts, TGF-β may program a tolerogenic phenotype in the local APCs. Following i.v. administration, PLG NPs associate with APCs of the liver and spleen.10 In the liver, Kupffer cells and liver sinusoidal endothelial cells are commonly associated with PLG NP uptake and each are natural producers of TGF-β.35–38 In the spleen, PLG NPs have been reported to be scavenged by macrophages in the marginal zones where they present Ag to T cells. This context of presentation has been implicated in tolerance induction through T cell anergy and Treg production.6 The same NPs, injected s.c., will interact with immune cells in a different context. NPs with diameters greater than 100 nm do not passively flow to the lymph nodes, but instead are internalized by APCs and infiltrating mononuclear cells that traffic to the lymph nodes.39,40 Implanted PLG microporous scaffolds cause a similar recruitment of monocytes, macrophages, and DCs.41 Experiments delivering soluble TGF-β from the scaffolds demonstrated a significant decrease in the number of infiltrating leukocytes, chemoattractants, and activating cytokines.42 Thus, delivery of TGF-β with Ag-NPs may be acting to reduce the inflammatory context of Ag presentation in the draining lymph node. Together, i.v. and s.c. administration of TGF-β-coupled NPs result in similar patterns of disease abrogation, yet may affect tolerance by different cell types due to differences in their biodistribution.

Ag-NP administration resulted in Ag-specific changes to the T cell compartment. EAE and MS are T cell-mediated diseases.32 As such, a single infusion of myelin-specific CD4+ T cells is sufficient for inducing relapsing and remitting EAE.9 Therefore, many Ag-specific therapies attempt to reprogram the context of MHC class II presentation to CD4+ T cells to induce T cell unresponsiveness and expansion of Tregs. Tolerance induction by Ag-NPs is partly dependent on CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Treg production, and inactivating Tregs with anti-CD25 antibodies reduced the effectiveness of NP-induced tolerance.6 TGF-β is required for the differentiation of Tregs in vitro, so NP-treated mice were investigated for in vivo-expanded CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Tregs. Indeed, mice treated with Ag-NPs did experience an expansion of CD4+ T cells and Tregs; however, the presence of TGF-β on the NPs did not further augment the Foxp3+ Treg numbers (Figure 4). This observation is consistent with others who have enhanced tolerogenic outcomes without expanding Foxp3+ Tregs.19,43,44 Foxp3+ Tregs were investigated due to their close association with TGF-β, but future studies would benefit from studying Foxp3− T cells with regulatory potential.

TGF-β-coupled Ag-NPs administered i.v. and s.c. at intermediate doses attenuated relapse symptoms, yet not the initial EAE disease onset. Previously, Ag-coupled PLG NPs demonstrated that EAE disease abrogation was proportional to NP dose, and the severity of the acute disease symptoms was correlated with the severity of the relapse symptoms.9 These data were consistent with the theory of epitope spreading in which the severity of relapse symptoms is directly related to the extent of myelin destruction in the acute phase.45 This proportionality between acute and relapse scores was also observed in this investigation in the control mice treated with NPs containing irrelevant Ag or disease-relevant Ag without TGF-β. However, mice treated i.v. or s.c. with TGF-β-coupled particles experienced relapse symptoms that were disproportionately less severe than the symptoms of the acute phase (Figures 5 and 6), which may indicate that TGF-β causes a reduction in the degree of acute phase tissue destruction that leads to epitope spreading. This role for TGF-β is supported by others who observed limited extravasation of inflammatory cells into the CNS following injections of soluble TGF-β.23 Others have demonstrated tolerance induction by s.c. administration of particles by delivering other immunomodulators such as antisense RNA (anti-CD80, anti-CD86, and anti-CD40), IL-10, or immunosuppressive agents such as rapamycin.7,19,20 The current platform is an advance relative to our previous strategies because it incorporates Ag and TGF-β into a single NP ensuring the immunosuppressive effects are in the context of Ag presentation. Additionally, TGF-β is endogenously present in mice and humans, so the delivery of TGF-β as an immunomodulator takes advantage of natural peripheral tolerance pathways.37,38 Together, for TGF-β-coupled Ag-NPs, a critical particle dose may be required for abrogating acute EAE symptoms, and the codelivery of TGF-β may limit the severity of relapse symptoms by reducing the degree of CNS destruction in the acute phase of disease.

In conclusion, TGF-β was conjugated to the surface of PLG NPs produced with precise Ag-loadings. The resulting (acPLGAg)-TGF-β NPs incorporate Ag and TGF-β in a fashion that maintains independent tunability and bioactivity. In vitro, BMDCs treated with (acPLG-Ag)-TGF-β NPs provided Ag-specific T cell stimulation, decreased costimulatory molecule presentation, and suppressed inflammatory cytokine secretions. In EAE, prophylactic i.v. treatment with (acPLG–PLP)-TGF-β NPs reduced clinical scores in low dose regimes, and (acPLG–PLP)-TGF-β NPs delivered s.c. reduced clinical disease scores without the use of broad-acting immunosuppressive drugs. Importantly, the tolerogenic effects of TGF-β in this NP codelivery platform were Ag-specific. Together, this study supports the use of immunomodulatory cytokines to enhance the efficacy of Ag-specific tolerance therapies.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials.

Poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (50:50) (PLG) with a single carboxylic acid end-group and an inherent viscosity of 0.17 dL/g in hexafluoro-2-propanol was purchased from Lactel Absorbable Polymers (Birmingham, AL). Poly(ethylene-alt-maleic anhydride) (PEMA) was purchased from Polyscience, Inc. (Warrington, PA). Amine-terminated ovalbumin peptide (NH2–OVA323–339) and proteolipid peptide (NH2–PLP139–151) was purchased from Genscript (Piscataway, NJ). N-Hydroxysulfosuccinimide (sulfo-NHS) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA). Recombinant mouse transforming growth factor beta 1 (TGF-β) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless noted otherwise.

Ag-PLG Conjugation.

Peptide–polymer conjugates (Ag-PLG) were made as previously described.11 Briefly, PLG (37.8 mg, 0.009 mmol, 4200 g/mol) of was dissolved in 2 mL of N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF). N-(3-(Dimethylamino)propyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC) (9.0 mg, 0.047 mmol, 5× to PLG) was dissolved in 0.5 mL of DMF and added dropwise to the PLG solution. N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)(5.5 mg, 0.047 mmol, 5× to PLG) was dissolved in 0.5 mL DMF and added dropwise to the solution. The reaction was stirred for 15 min at room temperature. Antigenic peptide(1.2× to PLG) was dissolved in a solution of 1 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and 0.5 mL DMF and stirred at 400 rpm. Triethylamine (5× to peptide) was added to peptide solution and the mixture was added dropwise to the stirring PLG solution. The reaction was allowed to proceed overnight at room temperature. The resulting polymer was isolated and purified by dialysis using 3500 molecular weight cutoff membrane against distilled water. The dialyzed polymer was collected and washed with Milli-Q water three times by centrifugation at 7000g before lyophilization. The coupling efficiency of peptide to PLG was determined by 1H NMR analysis in DMSO-d6.

Mice.

Female SJL/J mice (6–8 weeks) were purchased from Envigo (Indianapolis, IN). C57BL/6J mice (6–8 weeks) and OT-II mice (B6.Cg-Tg(TcraTcrb)425Cbn/J) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All mice were housed under specific pathogen-free conditions in the University of Michigan Unit for Laboratory Animal Medicine and maintained according to protocols approved by the University of Michigan Animal Care and Use Committee.

Nanoparticle Preparation and TGF-β Conjugation.

Ag-polymer conjugate PLG (acPLG) NPs and Ag-encapsulated PLG [PLG(Ag)] NPs were prepared using a single and double emulsion solvent evaporation (S.E.) method, respectively. These SE methods have been described in our previous publications.9–11 Briefly, acPLG NPs were produced using the SE method with Ag-PLG conjugates combined with unmodified PLG at various ratios to produce acPLG NPs with predefined Ag loadings. PLG(Ag) NPs were produced by encapsulating peptides in a two-step SE method.10 Cryoprotectants (4% (w/v) sucrose and 3% (w/v) mannitol) were then added to the particles before lyophilization. Prior to TGF-β conjugation, NPs were washed and resuspended with Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (PBS) (Gibco, Waltham, MA) to 5 mg/mL. EDC (128 ng, 0.668 nmol, 100× to TGF-β) and sulfo-NHS (14.5 ng, 0.067, 10× to TGF-β) were dissolved in PBS, added to the NPs, and allowed to react for 15 min at room temperature and mixed at 700 rpm (Eppendorf Thermomixer, Hamburg, Germany). TGF-β was suspended in PBS and added dropwise to the ester-activated NPs. After a reaction time of 1 h, NPs were washed 3 times with PBS. TGF-β loading was determined by quantification of uncoupled TGF-β recovered during the NP wash steps. TGF-β was measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (coupling efficiency 99.5%). NPs with titrated quantities of TGF-β were produced by proportionally scaling the quantities of TGF-β, EDC, and sulfo-NHS while keeping the quantity of NP constant. The size and zeta potential of the acPLG NPs were determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) by mixing 10 μL of a 25 mg/mL particle solution into 990 μL of Milli-Q water using a Malvern Zetasizer ZSP (Westborough, MA).

Cell Culture.

BMDC were generated from the bone marrow of C57BL/6J mice using the Lutz protocol.46 Media consisted of RPMI containing L-glutamine (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with penicillin (100 units/mL), streptomycin (100 mg/mL), 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen Corporation, Carlsbad, CA), and 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich). Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Peprotech, Rocky Hill, NJ) was added at 20 ng/mL, and media was added/changed on days 3, 6, and 8. Day 10 BMDCs were treated with NPs at 300 μg/mL. Following incubation, all wells were washed to remove excess particles and BMDCs were incubated in media alone or supplemented with 10 ng/mL IFNγ (Peprotech) and 10 ng/mL LPS (Sigma). After 4 days of coculture, the BMDCs were collected, stained for viability, MHC II, CD80, and CD86, and analyzed using flow cytometry. Cell culture supernatants were analyzed by ELISA for IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, TNFα, and TGF-β (University of Michigan Cancer Center Immunology Core).

Antibodies and Flow Cytometry.

All antibodies were purchased from Biolegend (San Diego, CA) unless noted otherwise. FcR blocking was performed with anti-CD16/32 antibody prior to staining with various combinations of the following antibodies: anti-CD4 (RM4–5), -CD25 (PC61), -Foxp3 (FJK-16s) (eBioscience, San Diego, CA) -CD80 (16–10A1) -CD86 (GL-1), -I-A/I-E (M5/114.15.2). Viability was assessed with fixable violet dead cell stain kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or 4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole, Dilactate (DAPI) (Biolegend). Foxp3 staining was performed with the Foxp3 Staining Buffer Set according to the manufacturer’s protocol (eBioscience). Flow cytometric data were collected using a Beckman Coulter CyAn ADP Analyzer. Analysis was performed using FlowJo software (FlowJo, Ashland, OR).

Cell Isolation and in vitro Treg Induction Assay.

Treg induction assays were carried out as previously described.11 CD4+CD25−Foxp3− T cells were isolated from the spleen of OT-II mice using a naïve CD4+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec, San Diego, CA). The assay was carried out in T cell media. T cell media was prepared similarly to DC media but without GM-CSF or β-mercaptoethanol and supplemented with 1 mM sodium pyruvate and 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). BMDCs (2 × 104/well) were seeded into 96-well round-bottom cell culture plates and incubated for 3 h with NPs at 300 μg/mL. Following incubation, all wells were washed to remove excess particles. Naïve T cells were added at 1:1 to the BMDCs. If OVA and TGF-β were not delivered by NPs, they were supplied in soluble form at 100 ng/mL OVA and 2 ng/mL TGF-β. After 4 days of coculture, the T cells were collected, stained for viability, CD4, CD25, and Foxp3, and analyzed using flow cytometry. Statistical differences between conditions were determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (p < 0.05).

Ex Vivo T Cell Analysis.

OT-II mice were injected i.v. (tail vein) or s.c. (4 sites over shoulders and hind limbs) with 1.25 mg of NPs or 200 μL of PBS. After 7 days, the mice were euthanized; and the liver, spleen, and pooled inguinal, brachial, and axillary LN cells were stained for viability, CD4, CD25, and Foxp3. The cells were analyzed using flow cytometry. Statistical differences between conditions within the same organ were determined by Fisher’s LSD test (p < 0.05).

EAE Disease Induction and Measurement.

EAE was induced by immunization with encephalitogenic peptides as previously described.47 To induce R-EAE with PLP139–151, mice were immunized by s.c. administration of 100 μL of 1 mg/mL PLP139–151/complete Freund’s adjuvant (CFA) (Difco, Detroit, MI) distributed over 3 spots on the nape and hind flanks of SJL/J mice. Disease severity in individual mice was assessed by blinded observers using a 0 to 5 point scale: 0 = no disease, 1 = limp tail or hind limb weakness, 2 = limp tail and hind limb weakness, 3 = partial hind limb paralysis, 4 = complete hind limb paralysis, 5 = moribund. Differences between disease courses of more than two treatment groups were analyzed for statistical significance using the Kruskal–Wallis test (one-way ANOVA nonparametric test) (p < 0.05). Statistical differences between two treatment groups were determined by the Mann–Whitney (two-tailed nonparametric) test (p < 0.05).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the University of Michigan Cancer Center Immunology Core Facility and the University of Michigan Biointerfaces Institute for technical support. This work was supported in part by NIH grants EB-013198 (to L.D.S. and S.D.M.) and NS-026543 (to S.D.M.), and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (JDRF). K.R.H. acknowledges support from the University of Michigan College of Engineering.

ABBREVIATIONS

- (acPLG-Ag)-TGF-β

acPLG NP with TGF-β conjugated to the surface

- acPLG

Ag-polymer conjugate NP

- Ag

antigen

- Ag-NP

Ag-containing NP

- Ag-PLG

Ag-PLG polymer conjugate

- APC

Ag presenting cell

- BMDC

bone marrow-derived dendritic cell

- CFA

complete Freund’s adjuvant

- CNS

central nervous system

- DC

dendritic cell

- EAE

relapsing-remitting experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis

- GM-CSF

granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- i.v.

intravenous

- IFNγ

interferon gamma

- LN

lymph node

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MBP

myelin basic protein

- MHC II

major histocompatibility complex class II

- MOG

myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NP

nanoparticle

- OVA

OVA323–339 peptide

- PLG(Ag)

Ag-encapsulated NP produced by double emulsion

- PLG(Ag)-TGF-β

PLG(Ag) NP with TGF-β conjugated to the surface

- PLG

poly(lactide-co-glycolide)

- PLG-TGF-β

blank PLG NP with TGF-β conjugated to the surface

- PLP

PLP139–151 peptide

- s.c

subcutaneous

- TGF-β

transforming growth factor beta 1

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

- Treg

CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.7b00624.

EAE data demonstrating minimum required Ag-NP dose for disease suppression (PDF)

The authors declare the following competing financial interest(s): R.M.P., S.D.M., and L.D.S. have financial interests in Cour Pharmaceuticals Development Co.

REFERENCES

- (1).Pearson RM, Casey LM, Hughes KR, Miller SD, and Shea LD (2017) In vivo reprogramming of immune cells: technologies for induction of antigen-specific tolerance. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev 114, 240–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Luo X, Miller SD, and Shea LD (2016) Immune tolerance for autoimmune disease and cell transplantation. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng 18, 181–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Peleg AY, Husain S, Kwak EJ, Silveira FP, Ndirangu M, Tran J, Shutt KA, Shapiro R, Thai N, Abu-Elmagd K, et al. (2007) Opportunistic infections in 547 organ transplant recipients receiving alemtuzumab, a humanized monoclonal CD-52 antibody. Clin. Infect. Dis 44, 204–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Calabrese LH, and Molloy ES (2008) Progressive multifocal leucoencephalopathy in the rheumatic diseases: assessing the risks of biological immunosuppressive therapies. Ann. Rheum. Dis 67, iii64–iii65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Adami J, Gäbel H, Lindelöf B, Ekström K, Rydh B, Glimelius B, Ekbom A, Adami H-O, and Granath F (2003) Cancer risk following organ transplantation: a nationwide cohort study in Sweden. Br. J. Cancer 89, 1221–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Getts DR, Martin AJ, McCarthy DP, Terry RL, Hunter ZN, Yap WT, Getts MT, Pleiss M, Luo X, King NJ, et al. (2012) Microparticles bearing encephalitogenic peptides induce T-cell tolerance and ameliorate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat. Biotechnol 30, 1217–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Maldonado RA, LaMothe RA, Ferrari JD, Zhang A-H, Rossi RJ, Kolte PN, Griset AP, O’Neil C, Altreuter DH, Browning E, et al. (2015) Polymeric synthetic nanoparticles for the induction of antigen-specific immunological tolerance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, E156–E165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Yeste A, Nadeau M, Burns EJ, Weiner HL, and Quintana FJ (2012) Nanoparticle-mediated codelivery of myelin antigen and a tolerogenic small molecule suppresses experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 109, 11270–11275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Hunter Z, McCarthy DP, Yap WT, Harp CT, Getts DR, Shea LD, and Miller SD (2014) A Biodegradable Nanoparticle Platform for the Induction of Antigen-Specific Immune Tolerance for Treatment of Autoimmune Disease. ACS Nano 8, 2148–2160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).McCarthy DP, Yap JW-T, Harp CT, Song WK, Chen J, Pearson RM, Miller SD, and Shea LD (2017) An antigen-encapsulating nanoparticle platform for T H 1/17 immune tolerance therapy. Nanomedicine 13, 191–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Pearson RM, Casey LM, Hughes KR, Wang LZ, North MG, Getts DR, Miller SD, and Shea LD (2017) Controlled Delivery of Single or Multiple Antigens in Tolerogenic Nanoparticles Using Peptide-Polymer Bioconjugates. Mol. Ther 25, 1655–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Tostanoski LH, Chiu Y-C, Gammon JM, Simon T, Andorko JI, Bromberg JS, and Jewell CM (2016) Reprogramming the local lymph node microenvironment promotes tolerance that is systemic and antigen specific. Cell Rep 16, 2940–2952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Bryant J, Hlavaty KA, Zhang X, Yap W-T, Zhang L, Shea LD, and Luo X (2014) Nanoparticle delivery of donor antigens for transplant tolerance in allogeneic islet transplantation. Biomaterials 35, 8887–8894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hlavaty KA, McCarthy DP, Saito E, Yap WT, Miller SD, and Shea LD (2016) Tolerance induction using nanoparticles bearing HY peptides in bone marrow transplantation. Biomaterials 76, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Smarr CB, Yap WT, Neef TP, Pearson RM, Hunter ZN, Ifergan I, Getts DR, Bryce PJ, Shea LD, and Miller SD (2016) Biodegradable antigen-associated PLG nanoparticles tolerize Th2-mediated allergic airway inflammation pre-and postsensitization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, 5059–5064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Getts DR, Shea LD, Miller SD, and King NJ (2015) Harnessing nanoparticles for immune modulation. Trends Immunol. 36, 419–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Plard J-P, and Bazile D (1999) Comparison of the safety profiles of PLA 50 and Me. PEG-PLA 50 nanoparticles after single dose intravenous administration to rat. Colloids Surf., B 16, 173–183. [Google Scholar]

- (18).Ferenz KB, Waack IN, Laudien J, Mayer C, Broecker-Preuss M, Groot H. d., and Kirsch M (2014) Safety of poly (ethylene glycol)-coated perfluorodecalin-filled poly (lactide-co-glycolide) microcapsules following intravenous administration of high amounts in rats. Results Pharma Sci 4, 8–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Cappellano G, Woldetsadik AD, Orilieri E, Shivakumar Y, Rizzi M, Carniato F, Gigliotti CL, Boggio E, Clemente N, Comi C, et al. (2014) Subcutaneous inverse vaccination with PLGA particles loaded with a MOG peptide and IL-10 decreases the severity of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Vaccine 32, 5681–5689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Phillips B, Nylander K, Harnaha J, Machen J, Lakomy R, Styche A, Gillis K, Brown L, Lafreniere D, Gallo M, et al. (2008) A microsphere-based vaccine prevents and reverses new-onset autoimmune diabetes. Diabetes 57, 1544–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Travis MA, and Sheppard D (2014) TGF-β activation and function in immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol 32, 51–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Johns L, Flanders K, Ranges G, and Sriram S (1991) Successful treatment of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis with transforming growth factor-beta 1. J. Immunol 147, 1792–1796. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Racke MK, Dhib-Jalbut S, Cannella B, Albert PS, Raine CS, and McFarlin DE (1991) Prevention and treatment of chronic relapsing experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by transforming growth factor-beta 1. J. Immunol 146, 3012–3017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Laouar Y, Town T, Jeng D, Tran E, Wan Y, Kuchroo VK, and Flavell RA (2008) TGF-β signaling in dendritic cells is a prerequisite for the control of autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 10865–10870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Keegan ME, Falcone JL, Leung TC, and Saltzman WM (2004) Biodegradable microspheres with enhanced capacity for covalently bound surface ligands. Macromolecules 37, 9779–9784. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Kuo R, Saito E, Miller SD, and Shea LD (2017) Peptide-conjugated nanoparticles reduce positive co-stimulatory expression and T cell activity to induce tolerance. Mol. Ther 25, 1676–1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Lewis JS, Roche C, Zhang Y, Brusko TM, Wasserfall CH, Atkinson M, Clare-Salzler MJ, and Keselowsky BG (2014) Combinatorial delivery of immunosuppressive factors to dendritic cells using dual-sized microspheres. J. Mater. Chem. B 2, 2562–2574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Yeo Y, and Park K (2004) Control of encapsulation efficiency and initial burst in polymeric microparticle systems. Arch. Pharmacal Res 27, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Kishimoto TK, Ferrari JD, LaMothe RA, Kolte PN, Griset AP, O’Neil C, Chan V, Browning E, Chalishazar A, Kuhlman W, et al. (2016) Improving the efficacy and safety of biologic drugs with tolerogenic nanoparticles. Nat. Nanotechnol 11, 890–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Farias AS, Spagnol GS, Bordeaux-Rego P, Oliveira CO, Fontana AGM, de Paula RF, Santos M, Pradella F, Moraes AS, Oliveira EC, et al. (2013) Vitamin D3 induces IDO+ tolerogenic DCs and enhances Treg, reducing the severity of EAE. CNS Neurosci. Ther 19, 269–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Henry E, Desmet CJ, Garzé V, Fievéz L, Bedoret D, Heirman C, Faisca P, Jaspar FJ, Gosset P, Jacquet AP, et al. (2008) Dendritic cells genetically engineered to express IL-10 induce long-lasting antigen-specific tolerance in experimental asthma. J. Immunol 181, 7230–7242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Robinson AP, Harp CT, Noronha A, and Miller SD (2014) The experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) model of MS: utility for understanding disease pathophysiology and treatment. Handb. Clin. Neurol 122, 173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Schneider A, Long SA, Cerosaletti K, Ni CT, Samuels P, Kita M, and Buckner JH (2013) In Active Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis, Effector T Cell Resistance to Adaptive Tregs Involves IL-6-Mediated Signaling. Sci. Transl. Med 5, 170ra15–170ra15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Curtsinger JM, and Mescher MF (2010) Inflammatory cytokines as a third signal for T cell activation. Curr. Opin. Immunol 22, 333–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Bissell DM, Wang SS, Jarnagin WR, and Roll FJ (1995) Cell-specific expression of transforming growth factor-beta in rat liver. Evidence for autocrine regulation of hepatocyte proliferation. J. Clin. Invest 96, 447–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Park J-K, Utsumi T, Seo Y-E, Deng Y, Satoh A, Saltzman WM, and Iwakiri Y (2016) Cellular distribution of injected PLGA-nanoparticles in the liver. Nanomedicine 12, 1365–1374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Böttcher JP, Knolle PA, and Stabenow D (2011) Mechanisms Balancing Tolerance and Immunity in the Liver. Dig. Dis 29, 384–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Horst AK, Neumann K, Diehl L, and Tiegs G (2016) Modulation of liver tolerance by conventional and nonconventional antigen-presenting cells and regulatory immune cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol 13, 277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Reddy ST, Rehor A, Schmoekel HG, Hubbell JA, and Swartz MA (2006) In vivo targeting of dendritic cells in lymph nodes with poly(propylene sulfide) nanoparticles. J. Controlled Release 112, 26–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Randolph GJ, Inaba K, Robbiani DF, Steinman RM, and Muller WA (1999) Differentiation of phagocytic monocytes into lymph node dendritic cells in vivo. Immunity 11, 753–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Azarin SM, Yi J, Gower RM, Aguado BA, Sullivan ME, Goodman AG, Jiang EJ, Rao SS, Ren Y, Tucker SL, et al. (2015) In vivo capture and label-free detection of early metastatic cells. Nat. Commun 6, 8094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Liu JM, Zhang J, Zhang X, Hlavaty KA, Ricci CF, Leonard JN, Shea LD, and Gower RM (2016) Transforming growth factor-beta 1 delivery from microporous scaffolds decreases inflammation post-implant and enhances function of transplanted islets. Biomaterials 80, 11–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Peine KJ, Guerau-de-Arellano M, Lee P, Kanthamneni N, Severin M, Probst GD, Peng H, Yang Y, Vangundy Z, Papenfuss TL, et al. (2014) Treatment of Experimental Auto-immune Encephalomyelitis by Codelivery of Disease Associated Peptide and Dexamethasone in Acetalated Dextran Microparticles. Mol. Pharmaceutics 11, 828–835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Huss DJ, Winger RC, Cox GM, Guerau-de-Arellano M, Yang Y, Racke MK, and Lovett-Racke AE (2011) TGF-β signaling via Smad4 drives IL-10 production in effector Th1 cells and reduces T-cell trafficking in EAE. Eur. J. Immunol 41, 2987–2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Vanderlugt CL, and Miller SD (2002) Epitope spreading in immune-mediated diseases: implications for immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Immunol 2, 85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Lutz MB, Kukutsch N, Ogilvie AL, Rößner S, Koch F, Romani N, and Schuler G (1999) An advanced culture method for generating large quantities of highly pure dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow. J. Immunol. Methods 223, 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Miller SD, Karpus WJ, and Davidson TS (2010) Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis in the Mouse. Curr. Protoc. Immunol, DOI: 10.1002/0471142735.im1501s88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.