Abstract

Background

Fluoroquinolones are among the most commonly used antibiotics for the treatment of respiratory infections. Because fluoroquinolones show bactericidal activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, there is concern that their use can delay the diagnosis of tuberculosis. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess whether empiric treatment with fluoroquinolones delays the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in patients with respiratory tract infections.

Objectives

The primary objective was to assess the delay in days in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis, among patients who received quinolones, compared to those who received non-fluoroquinolone antibiotics.

Methods

We included studies of adult patients treated with fluoroquinolones prior to a confirmed diagnosis of tuberculosis. We performed a literature search of 7 databases (including PubMed, Embase and Cochrane Library) with no language restrictions. We calculated an unweighted mean of estimate of difference in delay across all studies. For the studies for which the estimate was available as a mean with standard deviation, a weighted average using a random effects meta-analysis model was estimated.

Results

A total of 3983 citations were identified from the literature search; of these, 17 articles were selected for full-text review. A total of 10 studies were retained for the synthesis. These included 7 retrospective cohort studies and 3 case-control studies. Only one of these studies was from a high TB burden country, South Africa. The most commonly used fluoroquinolones were levofloxacin, gemifloxacin and moxifloxacin. The unweighted average of difference in delay between the fluoroquinolone group and non-fluoroquinolone group was 12.9 days (95% CI 6.1–19.7). When these differences were pooled using a random effects model, the weighted estimate was 10.9 days (95% CI 4.2–17.6). When stratified by acid-fast smear status, the delay was consistently greater in the smear-negative group.

Conclusion

Although results are variable, the use of fluoroquinolones in patients with respiratory infections seems to delay the diagnosis of TB by nearly two weeks. Consistent with the International Standards for TB Care, their use should be avoided when tuberculosis is suspected.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Fluoroquinolones, Diagnostic delay

1. Introduction

Fluoroquinolones are among the most widely used antibiotics [1] and they are commonly used for the treatment of respiratory tract infections. Because fluoroquinolones show bactericidal activity against Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, there is concern that their use can delay the diagnosis of tuberculosis. The literature on this topic has yielded variable results regarding this association. The International Standards for TB Care recommend against the use of fluoroquinolones in adults with suspected tuberculosis [2]; however, these recommendations may not be followed consistently, as shown in recent simulated patient studies from India [3], [4]. Moreover, both the IDSA/ATS as well as the European guidelines for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia include respiratory fluoroquinolones (moxifloxacin, gemifloxacin or levofloxacin) as a first-line treatment option for patient with co-morbidities [5], [6]. A previous meta-analysis on the topic was published in 2011 [7]; since then, new studies have been published, warranting an updated systematic review.

2. Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess whether empiric treatment with fluoroquinolones delays the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis in patients with lower respiratory tract infections.

The primary objective was to assess the delay in days in the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis, among patients who received fluoroquinolones, compared to those who were treated with non-fluoroquinolone antibiotics. We aimed to limit selection bias by restricting the comparison to patients who had received non-fluoroquinolone antibiotics only instead of patients who had not received any antibiotics. This was done to ensure comparability of both groups as patients may be subject to differential prescribing patterns and medical investigation procedures depending on their pre-test probability of tuberculo-sis as determined by their treating physician.

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [8] for the planning and execution of this study. With the assistance of a medical librarian (GG), we performed a literature search of seven databases (PubMed, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Biosis and Global health) with no language restrictions through to August 8th 2016. We excluded case series of less than 10 patients, as well as articles for which either the full text or information on diagnostic delay was not available.

The titles and abstracts of identified articles were screened independently by two reviewers (CH and LP) based on a prespecified protocol. Publications identified as relevant by at least one reviewer were searched for full-text appraisal. Two reviewers completed full-text evaluations, selected articles, and extracted the data independently. Study quality assessment was performed by two reviewers using a tool (Table 1) developed at McGill University for TB diagnostic delay studies [9]. Disagreement was resolved by consensus. Study authors were contacted in case of ambiguity or missing data, and for clarification of study methodology.

Table 1.

Study quality assessment of the ten studies included in the systematic review.

| Main author, publication year (reference) | Patient sampling |

Definition of delay* |

Definition of confirmation of TB diagnosis |

Dealing with confounding |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consecutive or random (low risk of bias) | Not consecutive or random (high risk of bias) | Not described (no description) | Clearly stated delay definition (low risk of bias) | Stated but delay definition unclear (high risk of bias) | No definition (no description) | Clearly stated method of Dx of TB (low risk of bias) | No definition (no description) | Potential confounders identified and adjusted for (low risk of bias) | Potential confounders not identified, or identified but not adjusted for (high risk of bias) | |

| Rush 2016 [11] | All cases included | Clearly stated | Culture or PCR | Confounders identified but not adjusted for | ||||||

| Wang 2015 [12] | All cases included | Clearly stated | 50–60% by culture or NAAT; rest by ICD code | Confounders identified but not adjusted for | ||||||

| Kim 2013 [13] | Not described | Clearly stated | Culture | Confounders identified but not adjusted for | ||||||

| Wang 2011 [14] | All cases included | Clearly stated | Culture | Confounders identified but not adjusted for | ||||||

| Jeon 2011 [15] | Not described | Clearly stated | Culture | Confounders identified but not adjusted for | ||||||

| Wang 2006 [16] | All cases included | Clearly stated | Culture | Yes, adjusted for smear status | ||||||

| Sierros 2006 [17] | All cases included; some cases later excluded re: availability of medical records or results | Clearly stated | Culture | Yes, adjusted for smear status | ||||||

| Golub 2005 [18] | All cases eligible but sampling strategy not described | Clearly stated | Culture | Confounders identified but not adjusted for | ||||||

| Yoon 2005 [19] | Not described | Clearly stated | Culture | Confounders identified but not adjusted for | ||||||

| Dooley 2002 [20] | All cases included | Clearly stated | Culture | Yes, adjusted for smear status | ||||||

The definition of delay varied between the studies: time of sputum collection to initiation of anti-TB medications: 2 studies; presentation to initiation of anti-TB medications: 5 studies; time of initiation of antibiotics to initiation of anti-TB medications: 2 studies; time of sputum collection to culture growth: 1 study

The data were analyzed with the use of Stata version 12.1 (Statacorp, Texas, USA). The main outcome for the analysis was delay in time of presentation to time of start of anti-tuberculosis therapy in the fluoroquinolone group compared to the non-fluoroquinolone group. The threshold for statistical significance was set at a p-value of 0.05. First, an unweighted average of the estimate of delay was calculated for all studies. Second, for the studies for which the estimate was available as a mean with standard deviation, a weighted average using a random effects meta-analysis model was estimated.

3. Results

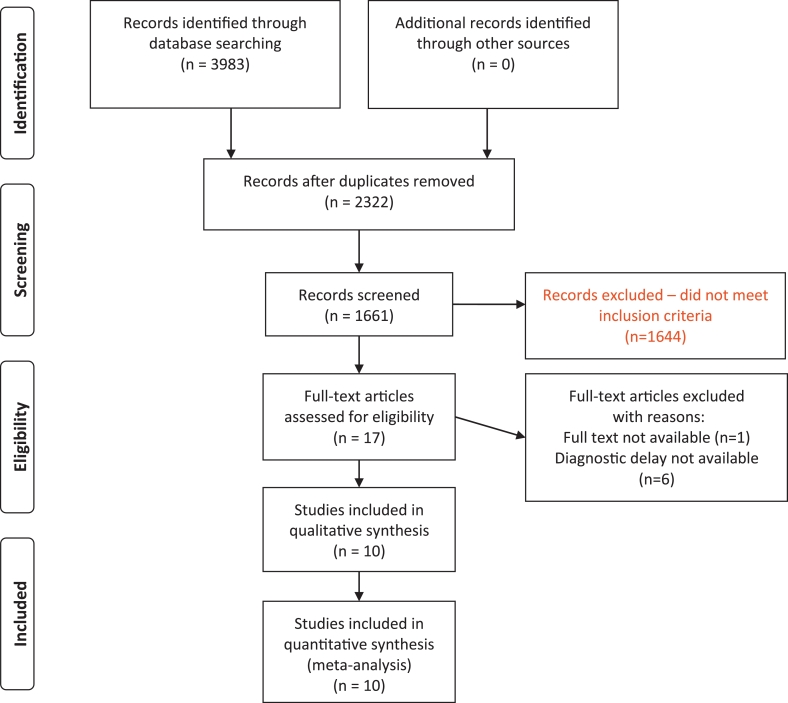

A total of 3983 citations were identified from the literature search; of these, 17 articles were selected for full-text review. A total of 10 studies were retained for the synthesis (Fig. 1). These included 7 retrospective cohort studies and 3 case-control studies. Only one of the 10 studies was from a high TB burden country, South Africa. A total of 18,179 patients were included in the 10 studies. The proportion of male participants in the studies ranged from 54 to 99%; HIV seroprevalence ranged from 0 to 58%. The most commonly used fluoroquinolones were levofloxacin, gemifloxacin, moxifloxacin and ciprofloxacin.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

For most studies, study quality was considered fair for the definition of delay and for the definition of confirmation of diagnosis (Table 1). There was limited information available regarding patient sampling methods, as well as strategies to deal with potential confounders. In addition, most studies did not adjust their estimates of diagnostic delay by potential confounders.

The mean difference in delay in time of presentation to time of start of anti-tuberculosis therapy in the fluoroquinolone group compared to the non-fluoroquinolone group varied from 0d to 28d across the 10 studies (Table 2). The unweighted average of difference in delay was 12.9 days (95% CI 6.1–19.7). The estimate of delay was available as a mean with standard deviation for five of the ten studies. When the differences for these studies were pooled using a random effects model, the weighted estimate was 10.9 days (95% CI 4.2–17.6). When stratified by acid-fast smear status, the delay was consistently greater in the smear-negative group. Based on one study, there was suggestion of a proportional increase in the diagnostic delay based on the duration of fluoroquinolone exposure (18.3 days in the one-day exposure group; 23.1 days in the ≥ 5 day group). However, there was overlap in the confidence intervals around these estimates. Heterogeneity in the study design and outcomes was present although this was not statistically evaluated.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the ten studies included in the systematic review.

| Main author, publication year (reference) | Setting, country | Study design | Fluoroquinolone used (number of patients) | Antibiotics used in the non-fluoroquinolone group | Duration of fluoroquinolone exposure (mean (SD) or median (IQR) in days) | Time from presentation to initiation of anti-TB treatment (mean (SD) or median (IQR) in days) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | All patients | Difference between FQ and non-FQ groups (days) | AFB smear positive | AFB smear negative | |||||||

| Rush 2016 [11] | Inpatients, Canada | Retrospective cohort | Moxi (9) | N/A | N/A | FQ | 9 | 14 (IQR 3–33) | 12.0 | N/A | N/A |

| Non-FQ | 33 | 2 (IQR 1–5) | |||||||||

| Wang 2015 [12] | Inpatients and outpatients, Taiwan | Retrospective cohort | Levo (908), moxi (716), cipro (402), oflox (25) | Penicillins, cephalosporins, carbapenems, macrolides | ≥7 | FQ | 2051 | 63.0 (47.1) | 13.6 | N/A | N/A |

| Non-FQ | 14,632 | 49.4 (47.6) | |||||||||

| Kim 2013 [13] | Inpatients, South Korea | Case-control | Moxi (10), levo (4), cipro (2) | Cephalosporins, macrolides, beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor | 14 (IQR 7–37) | FQ | 16 | 35 (IQR 14–72) | 28.0 | N/A | N/A |

| Non-FQ | 32 | 7 (IQR 3–63) | |||||||||

| Wang 2011 [14] | Inpatients and outpatients, Canada | Retrospective cohort | Cipro, Levo, Moxi (N/A) | Macrolides, penicillins, sulfonamide, cephalosporins | N/A | FQ | 36 | 53.2 (53.6) | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Non-FQ | 258 | 53.4 (46.7) | |||||||||

| Jeon 2011 [15] | Inpatients and outpatients, South Africa | Retrospective cohort | Cipro, oflox (N/A) | N/A | ≥5 | FQ | 90 | 23.1 (28.9) | 3.3 | N/A | N/A |

| Non-FQ | 511 | 19.8 (30.1) | |||||||||

| Wang 2006 [16] | Inpatients, Taiwan | Retrospective cohort | Cipro (42), levo (21), moxi (16) | N/A | 9.5 (6.0) | FQ | 79 | 45.4 (37.3) | 17.7 | 15 (IQR 8–175) | 42 (IQR 6–233) |

| Non-FQ | 218 | 27.7 (30.5) | 6 (IQR 0–105) | 27 (IQR 0–198) | |||||||

| Sierros 2006 [17] | Inpatients and outpatients, USA | Retrospective cohort | Levo (17), cipro (2), gati (1) | Beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor, macrolides | 3 (no IQR) | FQ | 20 | N/A | 14 (smear-positive) | 32 (no IQR) | 46 (no IQR) |

| Non-FQ | 48 | N/A | 18 (no IQR) | 34.5 (no IQR) | |||||||

| Golub 2005 [18] | Inpatients and outpatients, USA | Case-control | N/A | Macrolides, cephalosporins, amoxicillin, TMP-SMX, clindamycin, vancomycin | N/A | FQ | 45 | 39.0 (no IQR) | 0.5 | N/A | N/A |

| Non-FQ | 40 | 38.5 (no IQR) | |||||||||

| Yoon 2005 [19] | Inpatients, South Korea | Case-control | Levo (7), cipro (2) | Cephalosporins, macrolides, beta-lactam/beta-lactamase inhibitor, aminoglycosides | 14.2 (8.3) | FQ | 9 | 43.1 (40.0) | 24.4 | N/A | N/A |

| Non-FQ | 19 | 18.7 (16.9) | |||||||||

| Dooley 2002 [20] | Inpatients and outpatients, USA | Retrospective cohort | Levo (11), trova (2), gati (1), cipro (1), cipro then trova (1) | Cephalosporins, macrolides, TMP-SMX | N/A | FQ | 16 | 21 (IQR 5–32) | 16 | 9 (no IQR) | 24 (no IQR) |

| Non-FQ | 17 | 5 (IQR 1–16) | 1 (no IQR) | 16 (no IQR) | |||||||

SD: standard deviation; IQR: inter-quartile range; moxi: moxifloxacin; N/A: not available; FQ: fluoroquinolone; levo: levofloxacin; gati: gatifloxacin; trova: trovafloxacin; cipro: ciprofloxacin; gemi: gemifloxacin; oflox: ofloxacin; USA: United States of America; TMP-SMX: trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole

4. Discussion

A previous systematic review and meta-analysis on this topic was published in 2011 [7], and reported a mean diagnostic delay of 19.0 days (95% CI 10.9–27.2). This systematic review serves as an update with the addition of six new studies. Our mean diagnostic delay of 12.9 days (95% CI 6.1–19.7) also supports fluoroquinolones contributing to the diagnostic delay of tuberculosis. However, heterogeneity across studies suggests that this pooled estimate must be interpreted with caution.

The most plausible mechanism to explain this observed delay relates to the bactericidal activity of fluoroquinolones against Mycobacterium tuberculosis [17], thus delaying the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Moreover, fluoroquinolones may transiently improve the respiratory symptoms of tuberculosis, also contributing to delay. In vitro experiments have demonstrated that the bactericidal power of moxifloxacin and levofloxacin against Mycobacterium tuberculosis far outweighs that of ciprofloxacin [10].

The potent bactericidal activity of moxifloxacin in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis has made it a candidate of choice for the new short-course studied regimens, including PAMZ (pretomanid, moxifloxacin and pyrazinamide; currently in phase (3) and BPaMZ (bedaquiline, pretomanid, moxifloxacin and pyrazinamide; currently in advanced phase (2). As such, there is a compelling drive to protect quinolones from possible emerging resistance, an outcome this study did not assess.

The suggestion of a proportional relationship between the duration of fluoroquinolone exposure and delay in tuberculosis diagnosis is interesting and deserves further attention. The only study [15] that reported on the diagnostic delay of tuberculosis as a function of time categorized fluoroquinolone use by 1 day, 2–4 days and ≥ 5 days. There was a trend toward longer diagnostic delay in the group treated for ≥ 5 days compared to the two other groups; however, the confidence intervals overlapped around these estimates. This suggests that there may be a benefit in stopping the fluoroquinolone at the beginning of treatment if one thinks of tuberculosis as a diagnostic possibility even after the start of empiric antibacterial treatment.

Our study presents certain limitations. In particular, there was important variation in study settings, patient populations and in the definitions of delay used for the studies. Generalizability may also be limited given that only one study was from a high TB incidence country. Most studies reported delay as defined by the time to initiation of treatment; as such, the extra time between time of diagnosis and time of initiation of treatment is not adequately captured. In addition, data were lacking on variables such as delay in obtaining a diagnostic procedure (bronchoscopy or sputum induction), and on potential confounders (e.g. smear status, previous tuberculosis). Sufficient information was not available to stratify the meta-analysis diagnostic delay estimate by HIV status.

Furthermore, we attempted to limit bias by restricting the comparison to patients who had received antibiotics only. Unfortunately, this restriction was not possible for two studies [17], [20] where the groups were mixed with those having received non-fluoroquinolone antibiotics, and those not having received antibiotics. This information was not available for one study [15]. We recognize that physician behavior may play an important role in accelerating or not the investigations for a patient depending on the underlying suspicion of tuberculosis.

Finally, the study with the largest number of patients did not include culture diagnosis as necessary for inclusion in the study; this may have decreased power to detect a significant difference between the fluoroquinolone and non-fluoroquinolone groups. In addition, the approximation that medians and means were similar may not have been valid in the context of non-normally distributed data.

5. Conclusion

Although the available literature has several limitations and study results are heterogeneous, the evidence suggests that the use of fluoroquinolones in patients with respiratory infections might delay the diagnosis of active pulmonary TB by nearly 2 weeks. Consistent with the International Standards for TB Care, their use should be avoided when tuberculosis is suspected.

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors have any financial or industry conflicts. MP serves as a consultant to the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF). BMGF had no involvement this manuscript.

Funding

MP is supported by a Canada Research Chair award. This agency had no involvement in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy . CDDEP; Washington, D.C.: 2015. State of the world's antibiotics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tuberculosis Coalition for Technical Assistance. International standards for tuberculosis care (ISTC). The Hague: Tuberculosis Coalition for Technical Assistance, 2006.

- 3.Das J., Kwan A., Daniels B., Satyanarayana S., Subbaraman R., Bergkvist S. Use of standardised patients to assess quality of tuberculosis care: a pilot, cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(November(11)):1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Satyanarayana S., Kwan A., Daniels B., Subbaraman R., McDowell A., Bergkvist S. Use of standardised patients to assess antibiotic dispensing for tuberculosis by pharmacies in urban India: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30215-8. Aug 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mandell L.A., Wunderink R.G., Anzueto A., Bartlett J.G., Campbell G.D., Dean N.C. Infectious Diseases Society of America; American Thoracic Society. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27–S72. doi: 10.1086/511159. Mar 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodhead M., Blasi F., Ewig S., Garau J., Huchon G., Ieven M. Joint Taskforce of the European respiratory society and European Society for clinical microbiology and infectious diseases.Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections–full version. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17(November (Suppl 6)):E1–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2011.03672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen T.C., Lu P.L., Lin C.Y., Lin W.R., Chen Y.H. Fluoroquinolones are associated with delayed treatment and resistance in tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(March(3)):e211–e216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., The PRISMA Group Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qin, Z.Z. Delays in diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary tuberculosis, and patient care-seeking pathways in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Master's thesis. 2015.

- 10.Cremades R., Rodríguez J.C., García-Pachón E., Galiana A., Ruiz-García M., López P. Comparison of the bactericidal activity of various fluoroquinolones against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in an in vitro experimental model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(October(10)):2281–2283. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rush B., Wormsbecker A., Stenstrom R., Kassen B. Moxifloxacin use and its association on the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis in an inner city emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2016;50(March(3)):371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J.Y., Lee C.H., Yu M.C., Lee M.C., Lee L.N., Wang J.T. Fluoroquinolone use delays tuberculosis treatment despite immediate mycobacteriology study. Eur Respir J. 2015;46(August(2)):567–570. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00019915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim S.Y., Yim J.J., Park J.S., Park S.S., Heo E.Y., Lee C.H. Clinical effects of gemifloxacin on the delay of tuberculosis treatment. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28(March(3)):378–382. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.3.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang M., Fitzgerald J.M., Richardson K., Marra C.A., Cook V.J., Hajek J. Is the delay in diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis related to exposure to fluoroquinolones or any antibiotic? Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(August(8)):1062–1068. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.10.0734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeon C.Y., Calver A.D., Victor T.C., Warren R.M., Shin S.S., Murray M.B. Use of fluoroquinolone antibiotics leads to tuberculosis treatment delay in a South African gold mining community. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2011;15(January(1)):77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J.Y., Hsueh P.R., Jan I.S., Lee L.N., Liaw Y.S., Yang P.C. Empirical treatment with a fluoroquinolone delays the treatment for tuberculosis and is associated with a poor prognosis in endemic areas. Thorax. 2006;61(October(10)):903–908. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.056887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sierros V., Khan R., Joo Lee H., Sabayev V. The effect of fluoroquinolones on the acid-fast bacillus smear and culture of patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. Clin Pulm Med. 2006;13(May(3)):164–168. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golub J.E., Bur S., Cronin W.A., Gange S., Sterling T.R., Oden B. Impact of empiric antibiotics and chest radiograph on delays in the diagnosis of tuberculosis. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(April(4)):392–397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoon Y.S., Lee H.J., Yoon H.I., Yoo C.G., Kim Y.W., Han S.K. Impact of fluoroquinolones on the diagnosis of pulmonary tuberculosis initially treated as bacterial pneumonia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2005;9(November(11)):1215–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dooley K.E., Golub J., Goes F.S., Merz W.G., Sterling T.R. Empiric treatment of community-acquired pneumonia with fluoroquinolones, and delays in the treatment of tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(12):1607–1612. doi: 10.1086/340618. Jun 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]