Abstract

Tuberculosis (TB) is an airborne infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis that most commonly affects the lungs. However, extrapulmonary manifestations of TB can affect the eye and surrounding orbital tissues. TB can affect nearly any tissue in the eye, and a high index of suspicion is required for accurate diagnosis. Systemic anti-tuberculosis treatment is required in cases of ocular TB, and steroids are sometimes necessary to prevent tissue damage secondary to inflammation. Delays in diagnosis are common and can result in morbidities such as loss of an affected eye. It is important for ophthalmologists and infectious disease specialists to work together to accurately diagnose and treat ocular TB in order to prevent vision loss. This article reports the various known presentations of orbital and external ocular TB and reviews important elements of diagnosis and treatment.

Keywords: Tuberculosis, Mycobacterium, Orbit, Eye, Ocular

Review of the literature

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by the obligate aerobic, acid-fast bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis [1]. Transmission is airborne, and the lungs are the most commonly affected organ [2], [3]. However, there are many forms of extrapulmonary tuberculosis, including several varieties that affect the eye [4]. This review will focus on orbital and external ocular manifestations of TB.

Literature search strategy

The literature was reviewed using a PubMed search with both Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and keywords. MeSH terms included tuberculosis, ocular tuberculosis, orbital tuberculosis, eye infections and visual acuity. Keywords included eye, periocular, ocular, eyelid, conjunctiva, cornea, lacrimal gland, tuberculosis, “ocular tuberculosis,” and “orbital tuberculosis.” Results were limited to available peer-reviewed, English-language journals published between 1930 and 2015. All papers were reviewed, including single case reports.

Epidemiology and pathophysiology

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), approximately one third of the world's population is infected with TB. However, only 10% of those infected will develop clinical manifestations of the disease [5]. Of these, 16–27% have extrapulmonary manifestations, which includes those with orbital and external eye disease [6]. The precise incidence of ocular TB is much more difficult to discern, ranging from 1.4% to 18% in various studies [4], [7], [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. Risk factors for extrapulmonary TB include age over 40 years, female gender, and HIV infection [4]. Hematogenous spread from the lungs is the primary mechanism by which TB affects the orbit and eyes, but TB can also spread via direct local extension [13], [14], [15]. A hypersensitivity response from infection elsewhere in the body can affect the eyes and surrounding tissues as well [13].

External ocular involvement

TB can affect the orbit and external eyes in a wide variety of ways, which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical presentations of external ocular tuberculosis.

| Tissue | Possible presentations |

|---|---|

| Orbit | Periostitis |

| Soft tissue tuberculoma | |

| Bony destruction | |

| Orbital apex syndrome | |

| Lacrimal gland | Dacryoadenitis |

| Abscess | |

| Eyelid | Chronic blepharitis |

| Recurrent chalazion | |

| Diffuse infiltration resembling cellulitis | |

| Conjunctiva | Conjunctivitis |

| Subconjunctival nodules | |

| Polyps | |

| Tuberculomas | |

| Ulcers | |

| Phlyctenulosis | |

| Sclera | Nodular anterior scleritis |

| Diffuse anterior scleritis | |

| Scleromalacia | |

| Sclerokeratitis | |

| Sclerouveitis | |

| Posterior scleritis | |

| Cornea | Interstitial keratitis |

| Disciform keratitis | |

| Phlyctenulosis | |

| Corneal erosions |

Orbit

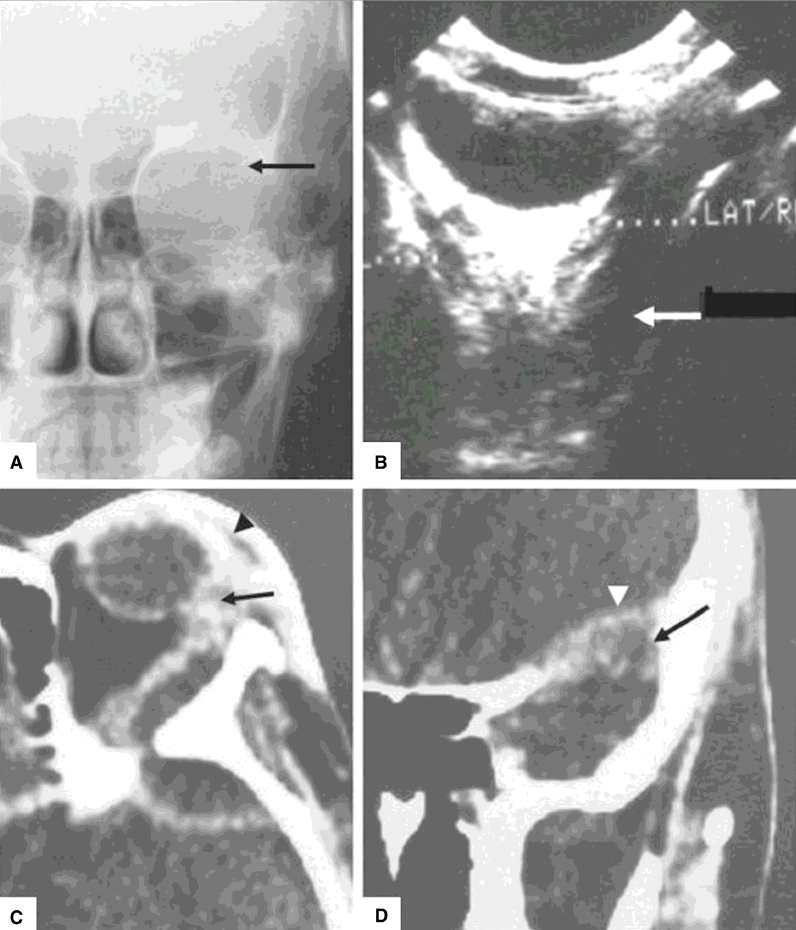

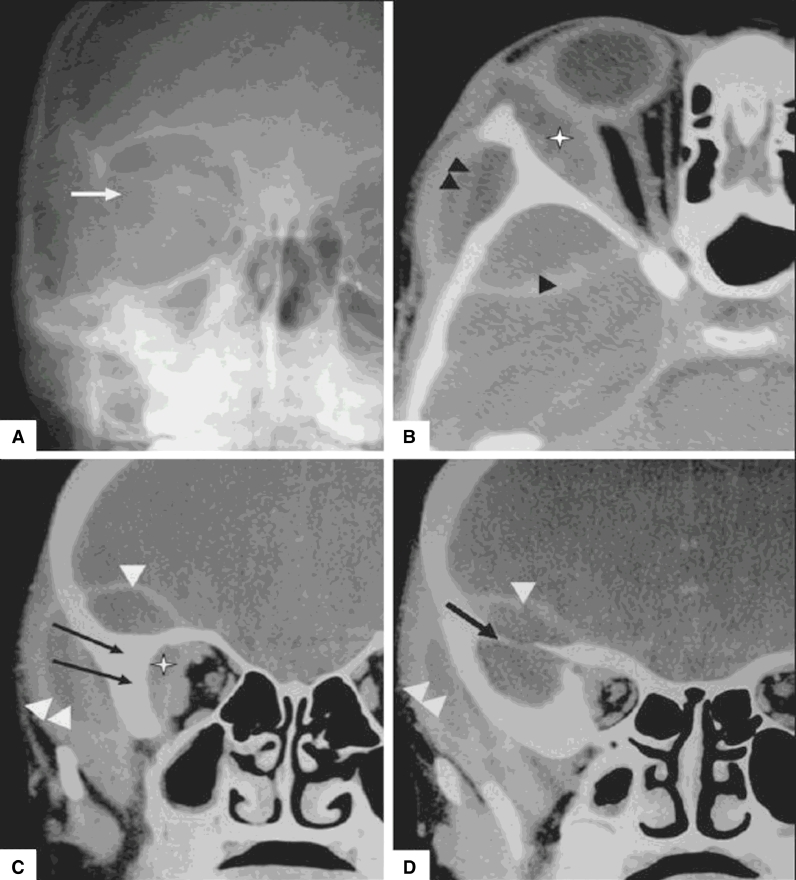

TB involvement of the orbit can present as proptosis secondary to mass effect (Fig. 1) or diplopia from cranial nerve or extraocular muscle involvement [16]. Orbital involvement is usually unilateral and is more common in children, but cases have also been reported in adults [17], [18]. Numerous pediatric cases of draining sinus tracts and radiographically-confirmed bony changes have been reported [19], [20], [21]. Involvement of the frontal, sphenoid, and zygomatic bones has been reported [17], [18], [19]. Boney involvement can be in the form of a tuberculous periostitis that typically affects the outer margin of the orbit, or it can manifest as cortical irregularities that later evolve into thickening and sclerosis of the orbital bones in longstanding cases [18], [22]. Extension of orbital tuberculosis into the cranium with extradural abscess formation can occur if the condition is allowed to progress (Fig. 2) [18], [23], [24], [25]. Caseating granulomas, soft tissue tuberculomas, and diffuse orbital involvement can also occur in both children and adults [20], [26], [27]. Finally, orbital apex syndrome has been reported, which can lead to severe vision loss [28].

Fig. 1.

Orbital tuberculosis presenting as proptosis. (A) Caldwell view x-ray shows bony destruction of the greater wing of the sphenoid (arrow). (B) B-scan ultrasonography reveals a retroorbital hypoechoic area in the extraconal space (arrow). (C) Axial contrast-enhanced CT demonstrates left-sided proptosis, lacrimal abscess (arrow), and preseptal thickening (arrowhead). (D) Coronal, contrast-enhanced CT scan further illustrates destruction of the greater wing of the sphenoid (arrow) and intracranial extension (arrowhead) [18].

Fig. 2.

Orbital tuberculosis with cranial extension and extradural abscess formation. (A) Caldwell view x-ray shows loss of definition of the greater wing of the sphenoid (arrow). (B–D) Axial (B) and coronal (C, D) contrast-enhanced CT scans reveal a right-sided extraconal and lacrimal abscess (asterisk in B, C), an intracranial extradural abscess (arrowhead), and an abscess in the infratemporal fossa region (double arrowhead). (C, D) Irregularity and sclerosis of the sphenoid and zygomatic bones (arrow) is also seen [18].

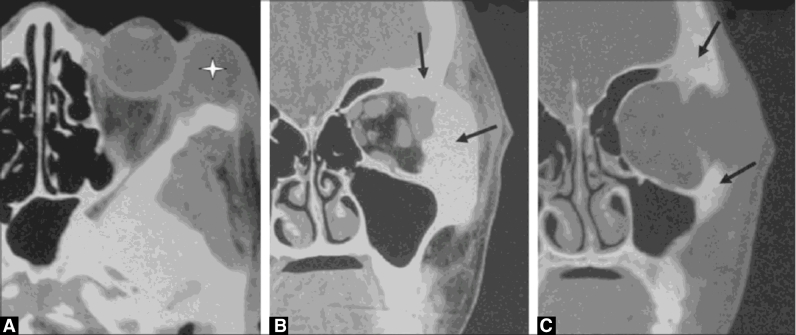

Lacrimal gland

The lacrimal gland can be affected in the form of dacryoadenitis [29]. The clinical presentation can be indistinguishable from bacterial dacryoadenitis, necessitating a high index of suspicion especially in cases that fail to respond to antibiotics [30]. Abscess formation can also occur (Fig. 3) [18]. Biopsy in these cases may reveal caseating granulomas [31].

Fig. 3.

Tuberculosis involvement of the lacrimal gland. (A) Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan shows a left lacrimal abscess (asterisk). (B, C) Coronal CT scans reveal irregularity, destruction, thickening, and sclerosis of the adjacent frontal and zygomatic bones (arrow) [18].

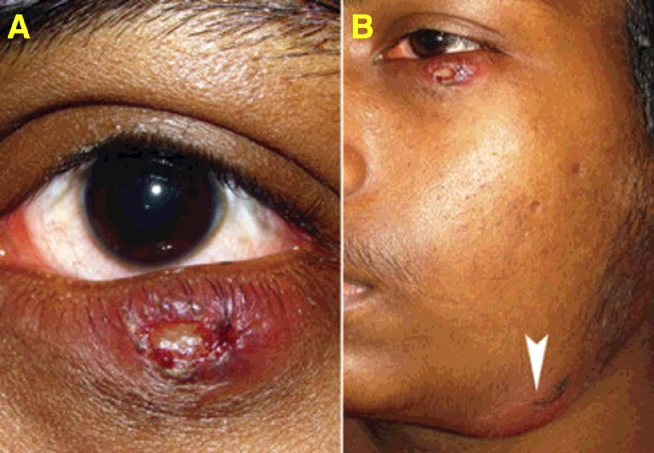

Eyelid

TB in the eyelid can manifest as chronic blepharitis or nodules resembling chalazia, which recur after excision (Fig. 4) [32], [33], [34], [35], [36]. Four such cases have been reported in the literature. Two cases were unilateral without evidence of systemic disease, and two cases were bilateral with associated pulmonary TB [32], [33], [34], [35]. Biopsy in such cases may reveal acid-fast bacteria, but caseating granulomas may be absent [35].

Fig. 4.

Eyelid involvement of tuberculosis. (A) Left lower eyelid wound with submandibular lymphadenitis in a patient with swollen, erythematous left lower eyelid with delayed eyelid wound healing after 1 week of incision and curettage for presumed chalazion. (B) Fluctuant, tender submandibular swelling (arrowhead, marked) in the same patient that developed 1 week after the photograph in A was taken [35].

TB can also involve the eyelid secondary to extension of cutaneous involvement, which can manifest as subepithelial nodules, plaques, or ulcers [37]. Diffuse infiltration of the eyelid resembling cellulitis has also been reported with a paradoxical worsening in response to typical TB treatment, which ultimately required systemic steroids [38].

Conjunctiva

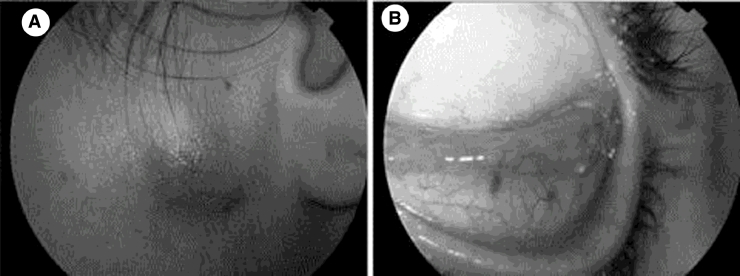

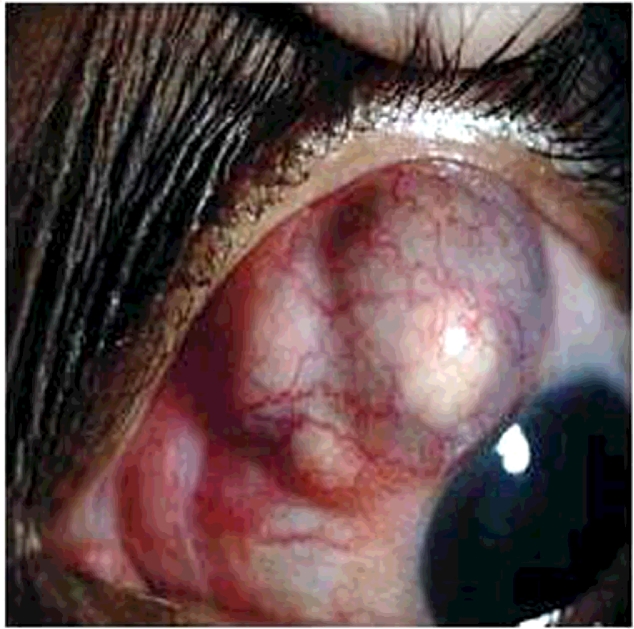

Conjunctival TB may present as conjunctivitis, subconjunctival nodules, polyps, tuberculomas, or ulcers (Figs. 5 and 6) [39], [40], [41], [42], [43], [44], [45], [46], [47]. While conjunctival involvement is more common in the setting of systemic disease, isolated conjunctivitis without systemic findings has been reported [48]. Phlyctenulosis can also occur as a hypersensitivity reaction that is not necessarily associated with active infection [49].

Fig. 5.

Lymphadenopathy and conjunctivitis caused by direct inoculation with M. tuberculosis. (A) Preauricular lymphadenopathy. (B) Tarsal hypertrophy indicative of conjunctivitis [85].

Fig. 6.

Tuberculosis manifesting as a conjunctival nodule in a 26-year-old female [46].

Sclera

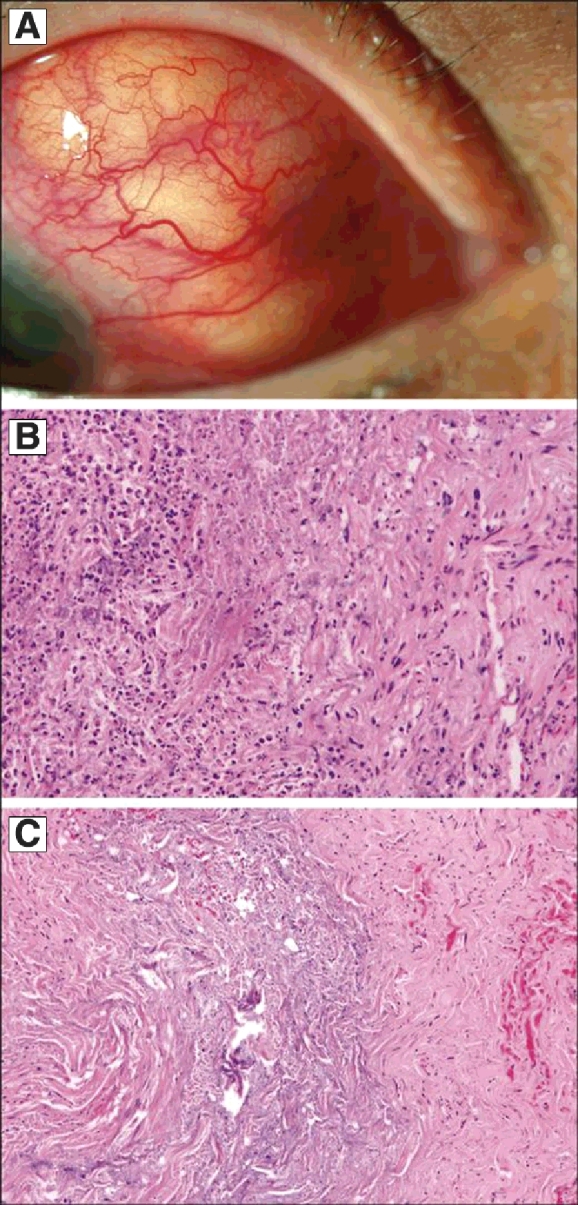

Scleritis and scleral nodules have been reported as ocular manifestations of TB (Figs. 7 and 8) [50], [51], [52], [53]. In fact, a previous study reported that TB was the causative agent in 10.6% of cases of infectious scleritis [31], [54]. Scleritis is usually anterior, but posterior scleritis secondary to TB has been described [54], [55]. Scleritis can be local or diffuse, but most cases are nodular [31], [56]. Lesions can also undergo necrosis, leading to scleral thinning [31], [56]. Spontaneous perforation due to necrotizing scleritis has been reported and may require enucleation [57]. Although scleral nodules have been hypothesized to represent an exaggerated immune response to TB elsewhere, direct infection has been proven in some cases, and pathological study has suggested that perforation occurs as a result of longstanding infection [52], [53], [55], [57], [58]. Scleritis may be associated with adjacent keratitis or uveitis [31]. TB can also affect the episclera in the form of nodular episcleritis [59].

Fig. 7.

Nodular scleritis caused by tuberculosis. (A) External photograph shows scleral nodules nasally and superiorly in the right eye. (B) Pathology and hematoxylin–eosin staining reveals a mixed inflammatory infiltrate in the sclera consisting of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and polymorphonuclear leukocytes with scleral necrosis. (C) A higher magnification of the hematoxylin–eosin stain reveals areas of scleral collagen necrosis [86].

Fig. 8.

Tuberculous scleritis in a 52-year-old female [89].

Cornea

Patients with corneal involvement can present with pain and photophobia, with exam findings consistent with deep stromal keratitis and corneal erosions [15], [60]. Patients can also develop interstitial keratitis, disciform keratitis, and phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis due to the body's immune response to the Mycobacterium [13], [61], [62].

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of ocular TB can be very difficult, as it can affect almost any part of the eye, and the clinical findings mimic those of a wide array of different underlying diseases, necessitating a complete workup to exclude other causes. Delays in diagnosis and initiation of appropriate ATT are common and may lead to significant vision loss or even loss of the eye [57]. Accurate diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion, review of associated systemic signs and symptoms, and appropriate laboratory testing. While there are no clearly defined criteria for the diagnosis of ocular TB, there are several factors that can support the diagnosis [13], [63].

Clinical signs

As discussed above, TB can manifest in a wide variety of ways in the orbit and external eye. In particular, TB should be suspected in the setting of multiple recurrences despite steroids or antibiotics.

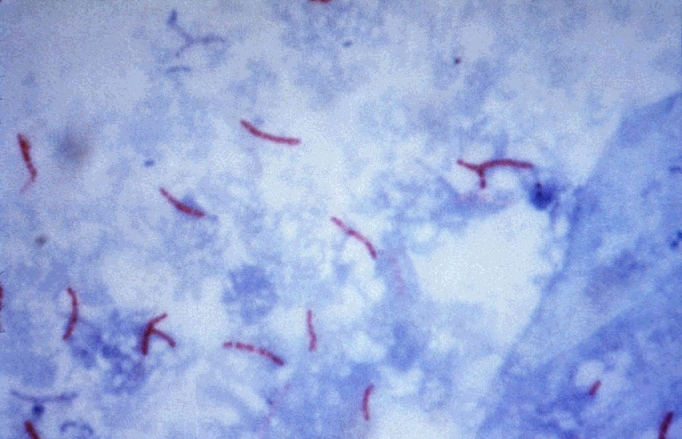

Acid-fast bacteria and histology

Acid-fast bacteria can sometimes be demonstrated via microscopy or Lowenstein-Jensen media culture of intraocular fluids or biopsied tissue, but yield is low [13], [14]. A Ziehl–Neelsen stain may reveal acid-fast bacilli (Fig. 9), particularly in areas of caseous necrosis; the necrotizing granulomas themselves are also an important indication of TB [8], [64].

Fig. 9.

A Ziehl–Neelsen stain reveals acid-fast bacilli, consistent with M. tuberculosis[87].

Polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction amplification of mycobacterial DNA can be particularly useful in ocular TB, where the sample size may be too small to detect the bacteria on microscopy or culture [47], [64], [65]. PCR is highly sensitive and specific and can be useful in the early diagnosis of ocular TB [14], [64], [66], [67], [68].

Mantoux skin test

A Mantoux skin test involves the intradermal injection of a purified protein derivative, followed by skin examination for cutaneous delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction 48–72 h after the injection (Fig. 10) [69]. The test is considered positive if the amount of induration measures greater than 5 mm in an HIV-positive patient, greater than 10 mm in high-risk persons, including healthcare workers, nursing home patients, and those living in endemic areas, and greater than 15 mm for all others [5]. In a rabbit model, cutaneous hypersensitivity has been shown to correlate directly with ocular hypersensitivity [70]. Unfortunately, this is a subjective test with low sensitivity and specificity [5]. Some patients, especially those who are immunocompromised, may have anergy to the protein and display no reaction, leading to false negative results [5]. Patients who have previously received Bacillus Calmette–Guerin (BCG) vaccinations, have been exposed to different species of mycobacteria, or who have received multiple Mantoux tests in the past, may have false positive reactions [5], [13]. However, the United States Preventative Services Task Force notes that induration greater than 10 mm should not be attributed to prior BCG vaccination [71].

Fig. 10.

A reactive Mantoux skin test is consistent with but not diagnostic of M. tuberculosis infection [88].

Interferon gamma testing

The QuantiFERON TB-Gold test (QFTG:Cellestis Ltd., Carnegie, Australia) is a blood test that detects TB and does not require a return office visit (versus the Mantoux skin test.) [72] This test specifically uses M. tuberculosis antigens to stimulate interferon gamma release from sensitized T cells in infected patients. The M. tuberculosis specific antigens used in this test will not yield false positive results for other mycobacteria or prior BCG vaccination [72], [73]. Nevertheless, due to a high rate of false positive results secondary to other factors, the CDC recommends the QuantiFERON test for screening only in patients who have been vaccinated with BCG or in those who are unlikely to return for skin test reading [74]. In studies of healthcare workers screened with QuantiFERON testing, the false positive rate was as high as 41%, and a study of HIV-positive patients revealed a false positive rate of 80.5% in those at low risk for TB [75], [76], [77], [78].

Chest x-ray and computerized tomography

Chest x-ray or computerized tomography of the chest demonstrating cavities, consolidation, or lymph node enlargement should heighten suspicion for primary TB infection [8]. Healed or reactivated TB lesions can also be observed, and any positive chest imaging finding should prompt sputum evaluation [79]. However, it is important to keep in mind that ocular TB can occur in the absence of pulmonary TB, and the majority of chest radiographs may be normal in these patients [1], [80].

Exclusion of other causes and response to treatment

It is always important to rule out other causes, such as syphilis and toxoplasmosis, when considering ocular TB [5]. Response to anti-tuberculosis treatment (ATT) may be the ultimate confirmation of ocular TB, but care should be taken not to commit patients to the required long courses of treatment without first ruling out other causes [5], [81].

Treatment

Medical treatment

Patients should be managed by both an ophthalmologist and an infectious disease specialist, as systemic treatment is required to manage ocular TB. Medical ATT for ocular TB is similar to that for pulmonary TB; however, relapses of ocular TB are common and may require extended courses of treatment [57]. The CDC recommends four-drug treatment with isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol for a total of 2 months, followed by an additional 4–7 months of dual therapy with isoniazid and rifampin [82]. The duration of therapy may be extended due to the typically slow response in ocular TB or in cases of multi-drug resistance [13]. In cases of multi-drug resistance or patient intolerance to any of the four recommended agents, rifabutin, fluoroquinolones, interferon gamma, and linezolid can also be of use [5]. In the past, ocular TB patients with latent TB received monotherapy in the form of isoniazid and/or rifampin rather than quadruple therapy; increasingly, infectious disease specialists are recommending quadruple therapy in part to reduce the development of multidrug resistant organisms [82]. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) supplementation should be used while patients are taking isoniazid to prevent peripheral neuropathy [83].

Ocular side effects of medical therapy

Patients should have a baseline eye exam prior to starting ATT and should be monitored for medication side effects, which can sometimes be confused with worsening ocular TB [5]. Both isoniazid and ethambutol can cause optic neuropathy, commonly manifesting as decreased visual acuity, decreased color vision, and/or cecocentral scotomas [84]. Other known side effects of ethambutol include optic neuritis, red-green dyschromatopsia, disc edema, and optic atrophy [5]. The development of these side effects should prompt discontinuation of the offending medication, as the side effects can be reversible, with vision often returning to normal 10–15 weeks after drug cessation [5]. Vitamin B12 can also be used to help return vision to normal, but in some cases vision loss may be permanent [5]. Rifabutin can cause anterior uveitis that typically responds well to topical steroid treatment; very rarely, intermediate or panuveitis has been reported in association with rifabutin [1].

Conclusion

TB is one of the great mimickers; thus ocular TB is often very difficult to diagnosis. TB can affect the orbit and external eye in a wide variety of ways, and accurate diagnosis and treatment are crucial to preventing permanent damage. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion, and ophthalmologists and infectious disease specialists should work together in the treatment of ocular TB.

Funding

Supported by Mayo Foundation, Rochester, MN; Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, NY; and the VitreoRetinal Surgery Foundation.

Acknowledgments

Ann M. Farrell for assistance with literature search.

Contributor Information

Lauren A. Dalvin, Email: Dalvin.lauren@mayo.edu.

Wendy M. Smith, Email: Smith.Wendy1@mayo.edu.

References

- 1.Tabbara K. Tuberculosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2007;18(6):493–501. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e3282f06d2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel J.D., Rhinehart E., Jackson M., Chiarello L., the Healthcare Infection Control Practicers Advisory Committee 2007 Guidelines for isolation precautions: preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007;35(Suppl. 2):S65–S164. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones R.M., Brosseau L.M. Aerosol transmission of infectious disease. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57(5):501–508. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanches I., Carvalho A., Duarte R. Who are the patients with extrapulmonary tuberculosis? Rev Port Pneumol. 2014;21(2):90–93. doi: 10.1016/j.rppnen.2014.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta V., Gupta A., Rao N.A. Intraocular tuberculosis – an update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2007;52(6):561–587. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.WHO . WHO; Geneva: 2013. Global tuberculosis report 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yeh S., Sen H.N., Colyer M., Zapor M., Wroblewski K. Update on ocular tuberculosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2012;23:551. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0b013e328358ba01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Helm C.J., Holland G.N. Ocular tuberculosis. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38:229. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(93)90076-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donahue H. Ophthalmologic experience in a tuberculosis sanatorium. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967;64:742. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)92860-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldenburg M., Fabricant N.D. The eye in the tuberculous patient. Trans Sect Ophthalmol Am Med Assoc. 1930;135:8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bouza E., Merino P., Muñoz P., Sanchez-Carrillo C., Yáñez J., Cortés C. Ocular tuberculosis. A prospective study in a general hospital. Medicine (Baltimore). 1997;76:53. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199701000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beare N.A., Kublin J.G., Lewis D.K., Schijffelen M.J., Peters R.P., Joaki G. Ocular disease in patients with tuberculosis and HIV presenting with fever in Africa. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86:1076. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.10.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharma A., Thapa B., Lavaju P. Ocular tuberculosis: an update. Nepal J Ophthalmol. 2011;3(5):52–67. doi: 10.3126/nepjoph.v3i1.4280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta A., Gupta V. Tubercular posterior uveitis. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2005;45(2):71–88. doi: 10.1097/01.iio.0000155934.52589.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sheu S.J., Shyu J.S., Chen L.M., Chen Y.Y., Chirn S.C., Wang J.S. Ocular manifestations of tuberculosis. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:1580–1585. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00693-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banait S., Jain J., Parihar P.H., Karwassara V. Orbital tuberculosis manifesting as proptosis in an immunocompromised host. Indian J Sex Transm Dis. 2012;33(2):128–130. doi: 10.4103/2589-0557.102129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pillai S., Malone T., Abad J.C. Orbital tuberculosis. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;11(1):27. doi: 10.1097/00002341-199503000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narula M.K., Chaudhary V., Baruah D., Mathuria M., Anand R. Pictorial essay: oribtal tuberculosis. Indian j Radiol Imaging. 2010;20(1):6–10. doi: 10.4103/0971-3026.59744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sen D. Tuberculosis of the orbit and lacrimal gland: a clinical study of 14 cases. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1980;17(4):232. doi: 10.3928/0191-3913-19800701-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khurana S., Pushker N., Naik S.S., Kashyap S., Sen S., Bajaj M.S. Orbital tuberculosis in a paediatric population. Trop Doct. 2014;44(3):148–151. doi: 10.1177/0049475514525607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Biswas J., Roy Chowdhury B., Krishna Kumar S., Lily Therese K., Madhavan H.N. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by polymerase chain reaction in a case of orbital tuberculosis. Orbit. 2001;20(1):69–74. doi: 10.1076/orbi.20.1.69.2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duke E. The ocular adnexa: lacrimal, orbital and paraorbital diseases. In: Duke-Elder S., editor. vol. 13. Henry Kimpton; London: 1974. pp. 902–905. (System of ophthalmology). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aggarwal D., Suri A., Mahapatra A.K. Orbital tuberculosis with abscess. J Neuroophthalmol. 2002;22:208–210. doi: 10.1097/00041327-200209000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gupta V., Angra P. Current Ophthalmology Proceedings of Delhi Ophthalmological Society (DOS) annual conference on ophthalmology update. 1995. Orbital tubercular abscess with intracranial extension; pp. 201–203. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dewan T., Sangal K., Premsagar I.C., Vashishth S. Orbital tuberculoma extending into the cranium. Ophthalmologica. 2006;220:137–139. doi: 10.1159/000090581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salam T., Uddin J.M., Collin J.R., Verity D.H., Beaconsfield M., Rose G.E. Periocular tuberculous disease: experience from a UK eye hospital. Br J Ophthalmol. 2015;99(5):582–585. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2013-304516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aversa do Souta A., Fonseca A.L., Gadelha M., Donangelo I., Chimelli L., Domingues F.S. Optic pathways tuberculoma mimicking glioma: a case report. Surg Neurol. 2003;60(4):349–353. doi: 10.1016/s0090-3019(03)00133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanawade R.G., Thampy R.S., Wilson S., Lloyd I.C., Ashworth J. Tuberculous orbital apex syndrome with severe irreversible visual loss. Orbit. 2015;16:1–3. doi: 10.3109/01676830.2015.1014505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Madhukar K., Bhide M., Prasad C.E., Venkatramayya Tuberculosis of the lacrimal gland. J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;94(3):150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Panda A., Singhal V. Tuberculosis of lacrimal gland. Indian J Pediatr. 1989;56(4):531. doi: 10.1007/BF02722435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta V., Shoughy S.S., Mahajan S., Khairallah M., Rosenbaum J.T., Curi A., Tabbara K.F. Clinics of ocular tuberculosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2015;23(1):14–24. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2014.986582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mocanu C. Tuberculosis of the tarsal conjunctiva. Oftalmologia. 1996;40:150–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozdal P.C., Codère F., Callejo S., Caissie A.L., Burnier M.N. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of chalazion. Eye (Lond) 2004;18:135–138. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aoki M., Kawana S. Bilateral chalazia of the lower eyelids associated with pulmonary tuberculosis. Acta Dermato-Venereol. 2002;82:386–387. doi: 10.1080/000155502320624195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mittal R., Tripathy D., Sharma S., Balne P.K. Tuberculosis of eyelid presenting as a chalazion. Ophthalmology. 2013;120(5):1103. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alvarez G.G., Roth V.R., Hodge W. Ocular tuberculosis: diagnostic and treatment challenges. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(4):432–435. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohan K., Prasad P., Banerjee A.K., Dhir S.P. Tubercular tarsitis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1985;33(2):115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seo Y., Choi M., Park C.K., Yoon J.S. A case of paradoxical reaction after treatment of eyelid tuberculosis. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2014;28(6):493–495. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2014.28.6.493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cook C.D., Hainsworth M. Tuberculosis of the conjunctiva occuring in association with a neighbouring lupus vulgaris lesion. Br J Ophthalmol. 1990;74(5):315. doi: 10.1136/bjo.74.5.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernandes M., Vemuganti G.K., Pasricha G., Bansal A.K., Sangwan V.S. Unilateral tuberculous conjunctivitis with tarsal necrosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121(10):1475. doi: 10.1001/archopht.121.10.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Singh I., Chaudhary U., Arora B. Tuberculoma of the conjunctiva. J Indian Med Assoc. 1989;87(11):265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaurasia S., Ramappa M., Murthy S.I., Vemuganti G.K., Fernandes M., Sharma S., Sangwan V. Chronic conjunctivitis due to Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int Ophthalmol. 2014;34(3):655–660. doi: 10.1007/s10792-013-9839-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maza A., Morel F., Pommier S., Vedy S., Lightburn E., Roux L., Patte J.H., Meye F., Morand J.J. Tubercular fibrosing conjunctivitis associated with facial cutaneous tuberculosis. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2008;135(10):679–681. doi: 10.1016/j.annder.2008.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pommier S., Chazalon E., Morand J.J., Meyer F. Chronic cicatrising conjunctivitis in a patient with hemifacial cutaneous tuberculosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92(5):616. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.132340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jennings A., Bilous M., Asimakis P., Maloof A.J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis presenting as chronic red eye. Cornea. 2006;25(9):1118–1120. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000240097.99536.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Babu R.B., Sudharshan S.S., Kumarasamy N., Therese L., Biswas J. Ocular tuberculosis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(2):413–418. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.03.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Biswas J., Kumar S.K., Rupauliha P., Misra S., Bharadwaj I., Therese L. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis by nested polymerase chain reaction in a case of subconjunctival tuberculosis. Cornea. 2002;21(1):123–125. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200201000-00027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rose J.S., Arthur A., Raju R., Thomas M. Primary conjunctival tuberculosis in a 14 year old girl. Indian J Tuberc. 2011;58(1):32–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Flocks M. Tuberculous lymphadenitis, allergic vasculitis and phlyctenulosis; report of a case. Calif Med. 1953;79(4):319–322. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sharma R., Marasini S., Nepal B.P. Tubercular scleritis. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2010;8(31):352–356. doi: 10.3126/kumj.v8i3.6228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Saini J.S., Sharma A., Pillai P. Scleral tuberculosis. Trop Geogr Med. 1988;40(4):350–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bloomfield S.E., Mondino B., Gray G.F. Scleral tuberculosis. Arch Ophthalmol. 1976;94(6):954–956. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1976.03910030482009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nanda M., Pflugfelder S.C., Holland S. Mycobacterium tuberculosis scleritis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108(6):736. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90875-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gonzalez-Gonzalez L.A., Molina-Prat N., Doctor P., Tauber J., Sainz de la Maza M.T., Foster C.S. Clinical features and presentation of infectious scleritis from herpes viruses: a report of 35 cases. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1460–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gupta A., Gupta V., Pandav S.S., Gupta A. Posterior scleritis associated with systemic tuberculosis. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2003;51:347–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tabbara K. Ocular tuberculosis: anterior segment. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2005;45:57–69. doi: 10.1097/01.iio.0000155935.60213.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Patel S.S., Saraiya N.V., Tessler H.H., Goldstein D.A. Mycobacterial ocular inflammation: delay in diagnosis and other factors impacting morbidity. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131(6):752–758. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wroblewski K.J., Hidayat A.A., Neafie R.C., Rao N.A., Zapor M. Ocular tuberculosis: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Ophthalmology. 2011;118(4):772–777. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bathula B.P., Pappu S., Epari S.R., Palaparti J.B., Jose J., Ponnamalla P.K. Tubercular nodular episcleritis. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2012;54:135–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aclimandos W.A., Kerr-Muir M. Tuberculous keratoconjunctivitis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76(3):175. doi: 10.1136/bjo.76.3.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamal S., Kumar R., Kumar S., Goel R. Bilateral interstitial keratitis and granulomatous uveitis of tubercular origin. Eye Contact Lens. 2014;40(2):e13–e15. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0b013e31827a025e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Arora R., Mehta S., Gupta D. Bilateral disciform keratitis as the presenting feature of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;2010(94) doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.157644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ustinova E. Fundamental principles of diagnosis, differential diagnosis, and treatment of ocular tuberculosis. Vestn Oftalmol. 2001;117:38–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Arora S.K., Gupta V., Gupta A., Bambery P., Kapoor G.S., Sehgal S. Diagnostic efficacy of polymerase chain reaction in granulomatous uveitis. Tuber Lung Dis. 1999;79(4):229–233. doi: 10.1054/tuld.1999.0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gupta V., Arora S., Gupta A., Ram J., Bambery P., Sehgal S. Management of presumed intraocular tuberculosis: possible role of the polymerase chain reaction. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 1998;76(6):679–682. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0420.1998.760609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Biswas J., Madhavan H.N., Gopal L., Badrinath S.S. Intraocular tuberculosis. Clinicopathologic study of five cases. Retina. 1995;15:461–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cassoux N., Charlotte F., Rao N.A., Bodaghi B., Merle-Beral H., Lehoang P. Endoretinal biopsy in establishing the diagnosis of uveitis: a clinicopathologic report of three cases. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2005;13(1):79–83. doi: 10.1080/09273940590909149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van Gelder R. Applications of the polymerase chain reaction to diagnosis of ophthalmic disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;46:248–258. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(01)00274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sakai J., Matsuzawa S., Usui M., Yano I. New diagnostic approach for ocular tuberulosis by ELISA using the cord factor antigen. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:130–133. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.2.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Woods A.C., Burky E.L., Friedenwald J.S. Experimental studies of ocular tuberculosis. Relation of cutaneous sensitivity to ocular sensitivity in the normal rabbit infected by injection of tubercle baccili into the anterior chamber. Arch Ophthalmol. 1938;19:245–250. [Google Scholar]

- 71.US Preventative Services Task Force . Guide to clinical preventative services. US Preventative Services Task Force; 1996. Screening for tuberculosis infection, including Bacille Calmette–Guerin immunization. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Albini T.A., Karakousis P.C., Rao N.A. Interferon-gamma release assays in the diagnosis of tuberculous uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:486–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2008.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kurup S.K., Buggage R.R., Clarke G.L., Ursea R., Lim W.K., Nussenblatt R.B. Gamma interferon assay as an alternative to PPD skin testing in selected patients with granulomatous intraocular inflammatory disease. Can J Ophthalmol. 2006;41(6):737–740. doi: 10.3129/i06-068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.(CDC) CfDCaP Updated guidelines for using interferon gamma release assays to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gray J., Reves R., Johnson S., Belknap R. Identification of false-positive QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-Tube assays in repeat testing in HIV-infected patients at low risk for tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54(3):e20–e23. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pai M., Joshi R., Dogra S., Mendiratta D.K., Narang P., Kalantri S. Serial testing of healthcare workers for tuberculosis using interferon-gamma assay. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174:349–355. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200604-472OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yoshiyama T., Harada N., Higuchi K., Nakajima Y., Ogata H. Estimation of incidence of tuberculosis infection in helath-care workers using repeated interferon-gamma assays. Epidemiol Infect. 2009;137:1691–1698. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809002751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zwerling A., van den Hof S., Scholten J., Cobelens F., Menzies D., Pai M. Interferon-gamma release assays for tuberculosis screening in healthcare workers: a systematic review. Thorax. 2011;67(1):62–70. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.143180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bramante C.T., Talbot E.A., Rathinam S.R., Stevens R., Zegans M.E. Diagnosis of ocular tuberculosis: a role for new testing modalities? Int Ophthalmol. 2007;47(3):45–62. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0b013e318074de79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Smith I. Mycobacterium tuberculosis pathogenesis and molecular determinants of virulence. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2003;16:463–496. doi: 10.1128/CMR.16.3.463-496.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Abrams J., Schlaegel T.F., Jr. The role of the isoniazid therapeutic test in tuberculous uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1982;94:511–515. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(82)90245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.(CDC) CfDCaP Treatment of tuberculosis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;51(RR-11):1–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Snider D.J. Pyridoxine supplementation during isoniazid therapy. Tubercle. 1980;61(4):191–196. doi: 10.1016/0041-3879(80)90038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Rodriguez-Marco N.A., Solanas-Alava S., Ascaso F.J., Martinez-Martinez L., Rubio-Obanos M.T., Andonequi-Navarro J. Severe and reversible optic neuropathy by ethambutol and isoniazid. An Sist Sanit Navar. 2014;37(2):287–291. doi: 10.4321/s1137-66272014000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Alcolea A., Suarez M.J., Lizasoain M., Tejada P., Chaves F., Palenque E. Conjunctivitis with regional lymphadenopathy in a trainee microbiologist. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(9):3043–3044. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02253-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kesen M.R., Edward D.P., Rao N.A., Sugar J., Tessler H.H., Goldstein D.A. Atypical infectious nodular scleritis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(8):1079–1080. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2009.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kubica G.P. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Ziehl–Neelsen stain 02:phil.cdc.gov CDC-PHIL ID #5789. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mycobacterium_tuberculosis_Ziehl-Neelsen_stain_5702.jpg#/media/File:Mycobacterium_tuberculosis_Ziehl-Neelsen_stain_5702.jpg [accessed 07.01.15].

- 88.Mantoux test:Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mantoux_test.jpg#/media/File:Mantoux_test.jpg [accessed 07.01.15].

- 89.Biswas J., Aparna A.C., Annamalai R., Vaijayanthi K., Bagyalakshmi R. Tuberculous scleritis in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2012;20:49–52. doi: 10.3109/09273948.2011.628195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]