Abstract

There are striking similarities between the dual pandemics of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR TB) and multidrug-resistant Gram negative bacilli (MDR GNB) despite fundamental differences in the pathogenesis and epidemiology of these pathogens. In this perspective, we highlight several strategies that have been used by the global TB community to address the MDR TB problem, including approaches to: encourage appropriate use of anti-TB medications, enhance appropriate utilization of molecular diagnostic testing, facilitate development of new antimicrobial agents, and strengthen surveillance systems and infection control practices. Understanding the successes and challenges of these strategies for MDR TB control will be instructive for efforts to curb emergence and spread of MDR GNB.

Keywords: Multidrug-resistant, MDR, Tuberculosis, TB, Gram negative bacilli, GNB

MDR TB and MDR GNB: disease burden

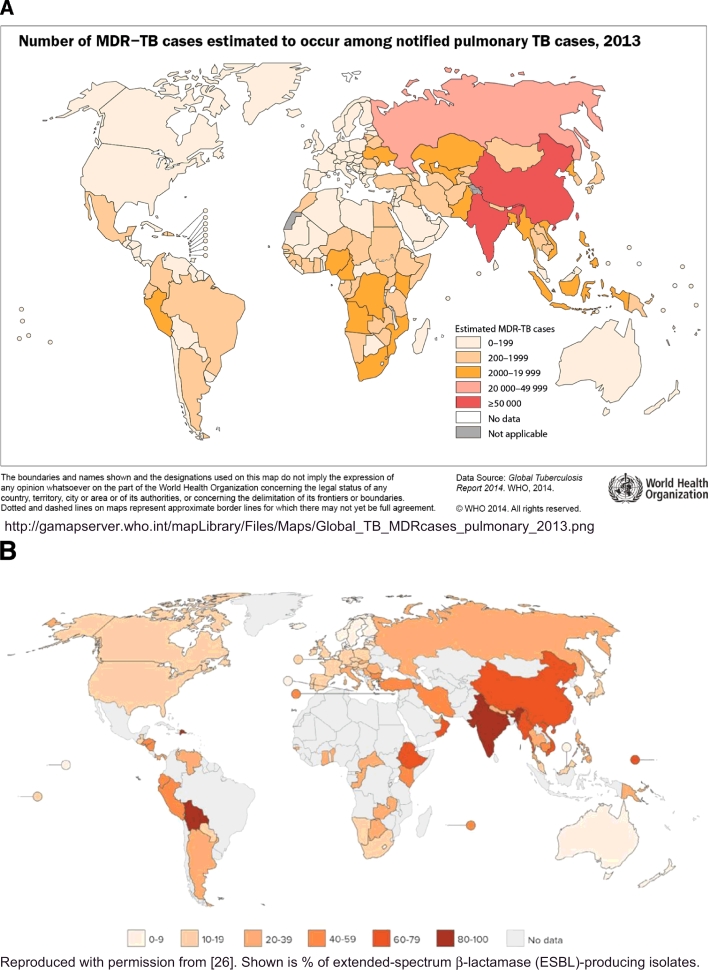

MDR TB was first recognized as a problem in the late 1990s and now affects roughly 500,000 people annually, accounting for 3% of new TB cases and 20% of previously treated TB cases worldwide [1]. Although 50% of the global burden of MDR TB occurs in India, China, and the Russian Federation [1] (Fig. 1), MDR TB and extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR TB) have emerged and spread worldwide, with transmission often facilitated through international travel. Foreign-born individuals account for 90% of US MDR TB cases [2] and stories of XDR TB patients traveling by commercial airlines make headlines [3]. As there are few new, effective drugs to treat these resistant strains, MDR/XDR TB patients receive second line agents that are more toxic and costly, and less effective than first line therapies. Globally, among patients with MDR TB who are initiated on therapy, only about half are successfully treated. In 2014 there were an estimated 190,000 deaths due to MDR TB [1]

Fig. 1.

MDR TB (A) and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing E. coli (B) are prevalent in similar regions of the world.

While attention has been focused on MDR TB for decades, the global emergence of other drug resistant bacteria has only recently been recognized as a public health emergency [4]. The press increasingly report stories about extensively drug-resistant bacteria that are resistant to most existing antibiotics and are thought to be “untreatable” [5], [6]. In 2014, President Obama's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology published a report calling antimicrobial resistance a national security threat that causes over 2 million illnesses, $20–35 billion in excess direct healthcare costs, $35 billion in loss of productivity, and 8 million additional hospital days each year in the US [7]. Worldwide, it is estimated that by 2050, 10 million people will die annually from antibiotic-resistant infections [8].

GNB are among the most alarming antibiotic-resistant pathogens as they are often resistant to multiple antibiotic classes and capable of rapidly spreading resistance genes through mobile genetic elements. For example, the pandemic emergence of the highly drug-resistant clone of Escherichia coli, sequence type 131 (ST131), occurred in less than 10 years [9]. Limited surveillance data suggest that in some regions of the world nearly 70% of GNB clinical isolates produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), which make them resistant to most β-lactam antibiotics [10], [11]. Even more alarming is that in some studies, resistance to carbapenems, known as last-resort antibiotics, has been reported in up to 68% of Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates [12], [13], [14], [15]. India, which has one quarter of the global burden of MDR TB, is also the epicenter of carbapenem-resistant, New Delhi-metalloprotease (NDM)-producing strains of Enterobacteriaceae [16], which have been found contaminating environmental sources [17]. As with MDR TB, international travel has facilitated spread of MDR GNB, with travel to regions of the world with high ESBL and carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) rates identified as a risk factor for acquisition of MDR GNB in several studies [18], [19], [20], [21], [22]. Similar to patients with MDR TB who must rely on second-line anti-TB drugs, those with MDR GNB often receive second-line agents that are more toxic and expensive but less effective than first-line therapies, contributing to poor outcomes. Mortality rates for carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections range from 18-48% [23], [24] compared to 10% for carbapenem-susceptible infections [25]. In India alone, drug-resistant pathogens, many of which are GNB, are estimated to cause 58,000 neonatal deaths [26].

MDR TB and MDR GNB are human-made problems

Both MDR TB and MDR GNB have arisen through missteps at the level of patients, providers, and health systems and are human-made problems. They have flourished in regions of the world with impoverished or poorly functioning healthcare systems and insufficient laboratory capacity that hinders rapid diagnosis, appropriate treatment and infection control interventions. These deficiencies, in turn, create further selection pressure for emergence and transmission of resistant pathogens [27], [28], [29]. The MDR TB and MDR GNB epidemics are multifactorial in origin, but the main causes are misuse of antimicrobial drugs and poor infection control technique.

The marked geographic variation in MDR TB prevalence is due to differences in the quality and influence of national TB programs. Regions with high MDR TB prevalence tend to have: poorly functioning national TB programs that do not routinely administer TB medications through Directly Observed Therapy (DOT) with subsequent poor patient adherence; poor quality of TB medications; a significant proportion of TB care given in the private sector; lack of laboratory capacity, medications, and access to healthcare; and inadequate infection control in healthcare facilities and congregate settings leading to sometimes profound and sustained transmission of MDR TB [30], [31].

Similarly, antibiotic misuse and poor infection control are the biggest drivers of GNB drug resistance. It is estimated that 60% or more of hospitalized patients or residents of long-term care facilities in the US receive antimicrobials and that up to half of these antimicrobial prescriptions are inappropriate [4], [32]. In US ambulatory settings, there are 11 million unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions given each year to children for management of viral respiratory tract infections [33]. Antibiotic abuse is even more rampant in low and middle income countries; these countries had the greatest increase in antibiotic use between 2000 and 2010 and tend to have the highest prevalence of MDR GNB (Fig. 1) [26]. India, followed closely by China, leads the world in total antibiotic consumption [26]. Not surprisingly, they also have the greatest number of MDR and XDR TB cases. Many low and middle income countries also have variable and often poor quality of healthcare, limited laboratory capacity, and poor quality antimicrobial agents that are commonly available over-the-counter, without a prescription [26], [27], [34], [35].

Throughout the world, antibiotics are also abused in agriculture, where they are used as growth promoters or for routine mass prophylaxis of livestock, thereby contributing to the rise in drug resistant pathogens. It is no surprise that many of the countries consuming the largest amounts of antibiotics for livestock (e.g. China, India, Russia) also have high prevalence of MDR GNB [14], [26]. In contrast, the European Union banned use of antibiotics as feed additives in agriculture in 2006 which led to substantial decreases in antibiotic sales for livestock in many countries in Western Europe [26]. There is some data from high income countries that decreased antibiotic use in farm animals is associated with lower prevalence of antibiotic resistant strains in humans [36]. Lastly, as with MDR TB, there are numerous examples of poor infection control leading to acquisition and spread of MDR GNB within healthcare settings [37], [38], [39], [40]. Enhanced infection control interventions such as active surveillance of infected or colonized individuals, and patient and/or staff cohorting were critical for halting outbreaks of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Israel [41] and the U.S. National Institutes of Health [40].

MDR TB in New York City: a success story in curtailing emergence and spread of drug resistance

New York City was the epicenter of MDR TB in the US in the 1980s and 1990s, largely due to a “perfect storm” of decreased funding for TB control programs, growth in HIV-infected, poor, homeless, and immigrant populations, and poor infection control in hospital settings [42] . Between 1978 and 1992 the number of TB cases in New York City tripled, reaching a case rate of 222/100,000 in some parts of the city [43]. The proportion of TB cases caused by MDR strains approached 25%, with case fatality rates of greater than 80% [43]. There was “massive noncompliance” among TB patients, with TB treatment completion rates as low as 11% [44]. In 1991, 61% of the nation's MDR TB cases occurred in New York City, and many were in individuals without previous TB treatment history, suggesting primary transmission of resistant strains. Moreover, several MDR TB outbreaks were documented in hospitals and congregate settings that lacked effective infection control procedures in both ambulatory and inpatient settings, and allowed crowding of inadequately treated TB patients.

Only after TB control programs were bolstered through increased funding (ultimately costing over $1 billion), did the epidemic in New York end [42]. Within two years of making programmatic improvements such as increased staffing, improved laboratory diagnostics, and better infection control, there was a substantial decrease in the number of TB cases. The city was able to provide TB therapy via DOT to more than 1200 patients by 1994, as opposed to fewer than 50 in 1983, leading to TB treatment completion rates above 90% [43]. Improved practices for screening, isolation, and follow-up of incarcerated individuals and better infection control in hospitals and congregate settings contributed to reduced transmission. Broader use of M. tuberculosis drug susceptibility testing and genotyping led to earlier diagnosis of drug resistance, more timely initiation of effective therapy, and understanding of transmission pathways. A combination of political commitment, sufficient funding, and infrastructure development were the cornerstones of controlling MDR TB in New York City, where nearly all MDR TB cases are now imported, rather than created locally [42].

Response to the MDR TB epidemic

The global TB community has responded to the emergence and spread of MDR TB through a variety of multidisciplinary strategies, as was done in New York City. It has been approached from both the personal health – such as adherence to therapy – and the public health points of view. Below we highlight core TB control strategies that are relevant to the management of the current epidemic of MDR GNB.

Antimicrobial stewardship

The phrase “antimicrobial stewardship” has usually been reserved for discussions of antibiotics like penicillins or cephalosporins and historically has not been used when referring to TB [45]. However, the global TB community has long been practicing stewardship of TB medications. It is well-known that among risk factors for drug-resistant TB disease are prior TB treatment, poor medication adherence, inadequate medication regimens or poor drug quality which can lead to subtherapeutic drug levels and acquired drug resistance. The World Health Organization, Stop TB Partnership, and Global Drug Facility began providing low resource areas with affordable, high quality TB medications, including pediatric formulations and second-line drugs for treatment of MDR TB in 2001 [46], [47]. Directly observed therapy (DOT) has been implemented by many public health departments worldwide for decades to improve TB treatment adherence and completion rates, and to lower the incidence of severe adverse drug reactions [48]. More recently, to provide DOT to difficult-to-reach populations, strategies such as video or smartphone-assisted-DOT and other eHealth innovations are being implemented [49]. Appropriate doses and durations of anti-TB therapy based on resistance phenotypes, patient characteristics, and clinical disease have been well-established through high quality and well-funded clinical trials, and are recommended in national and international TB treatment guidelines [50], [51]. Lastly, use of the novel and costly drug, bedaquiline, is restricted in order to prevent its overuse, preserve its activity, monitor its safety, and control costs [52]. All of the above strategies demonstrate that the TB community has embraced the concept of global antimicrobial stewardship of TB medications in order to optimize clinical outcomes, reduce transmission and toxicity, and prevent development of drug resistance.

Rapid diagnostic test development and implementation

One of the major barriers to timely TB diagnosis and treatment is limited laboratory capacity and lack of timeliness for M. tuberculosis identification and resistance detection in resource-limited settings. It is estimated that greater than 80% of MDR TB cases that arise each year remain microbiologically undiagnosed [53]. To address this limitation, significant resources have been invested in rapid, point-of-care molecular diagnostics for TB, leading to the development of line probe assays, fluorescence microscopy, liquid cultures, and the Xpert MTB/RIF assay [54]. Among these, the Xpert MTB/RIF assay, which simultaneously detects M. tuberculosis complex DNA and rifampin resistance (a reliable surrogate for MDR TB) [55] from clinical specimens within 2 h, and does not require specialized laboratory infrastructure or technologist skills, was selected for global roll-out. This assay was developed within 4 years through a collaboration among academic and industry partners, including Cepheid, FIND, University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation [54], [56], [57]. Critical for the development and programmatic implementation of this assay was the pooling of resources needed for test development, clinical validation trials, and field evaluations, and industry partners who agreed to flexible product pricing [57]. It was endorsed by the WHO in 2010 and soon after Ministries of Health of high TB burden countries developed guidelines, policies, and frameworks for Xpert MTB/RIF implementation [58].

Implementation of the Xpert MTB/RIF has led to a 3 fold increase in MDR TB case detection rates globally [59], with 116 countries using over 10 million Xpert MTB/RIF tests, including 4.8 million in 2014 alone [1], [60]. Yet while Xpert MTB/RIF is the most exciting innovation in TB diagnostics in over 100 years, and should, in theory, enable more timely diagnosis of MDR TB, facilitating prompt and optimal treatment for MDR TB patients, it has limitations, including inability to distinguish MDR isolates from those that have rifampin mono-resistance, or those containing rpoB mutations that are silent, clinically insignificant, or outside of the targeted region of the gene [61]. In addition, in some places the impact of Xpert MTB/RIF has been limited by cost, infrastructure, and health system challenges [62]. In response, the cost of required cartridges was recently reduced through a financial agreement among the manufacturer, the Gates foundation, USAID, PEPFAR, and UNITAID [63]. It has also become clear that enhancing systems throughout the care continuum of TB is essential for the Xpert MTB/RIF test to have optimal impact. For example, in India, although MDR TB case detection rates have increased since implementation of the Xpert MTB/RIF, only 20,000 of an estimated 64,000 patients with MDR TB were placed on appropriate therapy in 2013 [64]. Similarly, in South Africa, despite use of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay, only 70% of MDR TB patients were started on effective treatment within 1 month due, in part, to poor provider compliance with the national recommendation to order a second, confirmatory sputum sample [65].

Adoption of the Xpert MTB/RIF has been slow in certain regions in part due to distrust of the new test, lack of clarity about testing algorithms [66], [67], insufficient funding for programmatic scale up, and lack of available second-line TB treatments [68], [69]. As more MDR cases are diagnosed, countries must be able to treat patients with second line drugs, which are 50–200 times more costly per patient than are first line drugs [56] and often of poor quality [54], [57], [66]. Since the roll-out, studies have demonstrated that the performance, impact, and cost-effectiveness of the Xpert MTB/RIF test vary by disease prevalence, population, resources, and current testing and treatment algorithms [54]. It has become clear that to optimally impact the care of patients, rapid test development alone is not sufficient. Rather, systems must be in place to ensure access to new diagnostics, confirmation of rapid test results with standard culture and susceptibility testing, appropriate use and interpretation of rapid testing, and access to second-line drugs, when needed. Evaluation of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay's impact in various settings and different implementation models is ongoing [70].

New drug development

The pharmaceutical industry had, until recently, pulled out of the antimicrobial drug development market, stalling development of new antibiotics against Mycobacterium tuberculosis and other bacteria. The most recently developed first line drug for TB was rifampin which became available in 1968. In place of industry, government and non-government organizations such as the NIH and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation stepped up to fund translational research for TB drug development [57]. Not–for-profit product development partnerships were also created, including the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development, TB Drug Accelerator, the Lilly Early TB Drug Discovery Initiative, More Medicines for TB, and Orchid [53]. Several advocacy groups such as Treatment Action Group (http://www.treatmentactiongroup.org) and RESULTS (http://www.results.org/issues/global_health_tuberculosis/) were also instrumental in increasing political will and support for TB drug research. After 40 years without any new TB drugs, Bedaquiline, a diarylquinoline, received accelerated FDA approval in 2012 [71] and Delamanid, a nitroimidazole, received approval from the European Medicines Agency in 2013, both approved for treatment of MDR TB [53], [72]. In addition, PA-824, another nitroimidazole, will soon be evaluated in phase III clinical trials in combination with moxifloxacin and pyrazinamide. Shorter course TB therapy was evaluated in clinical trials and, in 2011, 3 months of once-weekly isoniazid and rifapentine was endorsed by the CDC for treatment of latent TB infection, the first new regimen in decades for the treatment of latent TB infection [73]. The recent successes in TB drug development underscore the importance of adequate investment in basic research, product development partnerships, economic incentives for pharmaceutical companies, an accelerated approvals process, infrastructure for clinical trials in order to maintain robust pipelines for antibacterial drug development, and the vital role of patient advocacy.

Enhanced surveillance

The World Health Organization (WHO) established a global TB reporting system in 1995 that has become invaluable to national and global TB programs. The 20th edition of the Global Tuberculosis Report was published this year and compiled TB data from 205 countries accounting for 99% of the world's population [1]. Even high TB burden countries like India have now instituted mandatory notification of TB cases [1]. This level of surveillance makes it possible to obtain national and global estimates of TB disease burden, drug resistance, treatment completion rates, and clinical outcomes [1]. Strengthening TB surveillance systems has thus helped identify areas for intervention, formulate national and global strategies for improved TB control, and allowed public health agencies to set attainable and measurable targets. For example, targets of halving TB mortality and TB prevalence in 2015 compared to 1990 were met in several WHO regions [1]. Other targets – that all countries report outcomes for notified MDR TB cases and that MDR TB treatment success rates exceed 75% – have not yet been met and require further programmatic efforts [1].

Infection control

As demonstrated by MDR TB management in New York in the 1990s, rapid diagnosis and effective treatment of patients with TB must be combined with effective infection control measures to reduce transmission of drug-resistant TB [31], [74], [75], [76]. A few studies in low resource, high TB prevalence areas demonstrate that community-based TB treatment is successful and avoids congregation in hospitals [77], [78], [79]. In South Africa, where nosocomial, drug-resistant TB outbreaks have occurred, home-based treatment for both MDR TB and HIV, with administration of medications by nurses and community health workers during home visits, yielded high treatment completion and cure rates [77]. Additional strategies include improving ventilation in healthcare facilities, optimizing outdoor waiting areas, building TB isolation facilities, redesigning patient triage and flow, reducing hospitalization times, and using germicidal ultraviolet air disinfection [30].

Response to the MDR GNB epidemic

The global response to antibiotic resistant GNB has been slow and disappointing, but now is focusing similar efforts on the same five strategies that have guided the approach used in TB: (1) enhanced antimicrobial stewardship; (2) development of rapid diagnostics that more quickly identify pathogens and detect drug resistance; (3) new antimicrobial development; (4) strengthened surveillance systems; and (5) enhanced infection control practices. While TB has always been recognized and approached as both a public health and personal health problem, traditionally GNB drug resistance has been approached only on a personal level; the public health approach has only recently been applied to GNB drug resistance. Earlier this year, the US National Strategy for Combating Antibiotic Resistant Bacteria was unveiled [80]. This action plan emphasizes several key areas and includes regulatory mandates and economic incentives to facilitate implementation [80].

The plan highlights the importance of strengthening antibiotic stewardship and tracking antibiotic use in humans and animals. This is analogous to how the TB community responded to MDR TB by becoming better stewards of TB medications through the provision of DOT and enhanced surveillance of treatment regimens, adherence and completion. In 2016, CMS will require all acute care hospitals to have an antimicrobial stewardship program and report data on inpatient antimicrobial use to the CDC's National Healthcare Surveillance Network. The National Strategy also cites the importance of conducting stewardship in all healthcare settings, including long-term and ambulatory care centers. Moreover, legislation has been introduced to the US Congress to eliminate nontherapeutic use of antibiotics in animals (Preventing Antibiotic Resistance Act) [81]. Additionally, the White House hosted a Forum on Antibiotic Stewardship, attended by a variety of stakeholders, including advocacy groups like the Safe Care Campaign (safecarecampaign.org), that have begun raising awareness about MDR GNB. Furthermore, last year the Obama Administration announced a $20 million prize for development of rapid, point-of-care diagnostics that identify drug resistant bacteria. Similar regulatory mandates, patient advocacy, and financial incentives for rapid diagnostic development were critical to the recent successes in TB care. However, as demonstrated by the variable impact of the Xpert MTB/RIF assay in different settings, methods to most effectively implement novel diagnostics for MDR GNB will require further study.

There has also been recent legislation providing economic incentives for pharmaceutical companies to reenter the antibacterial drug development arena. In part due to successfully lobbying by the Infectious Disease Society of America and its call for 10 new antibiotics by 2020 (10 × 20 initiative), the Generating Antibiotic Incentives Now (GAIN) Act, was passed in 2012 and offers a 5-year patent extension and an accelerated approval process for new antibacterial agents that are considered infectious disease products [82]. Legislation has also been introduced to accelerate the FDA approval process for antimicrobial agents for the treatment of patients with serious or life-threatening infections who have limited treatment options (Promise for Antibiotics and Therapeutics for Health (PATH) Act [83]. These efforts have met with some success, notably the recent FDA approvals of 2 new antibiotics with activity against resistant Gram negative bacteria, ceftolozane/tazobactam and ceftazidime/avibactam. Similar economic incentives and public/private partnerships were critical for new TB drug development.

More systematic evaluation of bacterial drug resistance at institutional, national, and global levels has been essential for MDR TB control and is incorporated into the National Action Plan for combatting antibiotic resistant bacteria [80]. The US plans to create regional public health laboratory networks to molecularly characterize resistant bacteria and has started a multisite Gram negative surveillance initiative through the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [23]. Europe has a multinational surveillance network called the European Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance network (EARS-Net) that collects and reports resistance data from national surveillance systems [15]. However, improved laboratory capacity and surveillance systems are badly needed in other parts of the world, particularly in low income nations with high prevalence of MDR GNB [15]. Some countries such as India and Vietnam have started developing national surveillance networks [15], [26]. The WHO provides free software for countries to collect and share their antibiotic resistance data (WHONET) (http://www.whonet.org), yet in the recent WHO report on global antimicrobial resistance, data were inconsistently reported [84]. Recognizing the gaps in antimicrobial resistance surveillance in many regions, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, that has supported much TB research, recently called for proposals involving novel methods to track the global burden of antimicrobial resistance.

Just as strengthening infection control practices have been critical to reducing transmission of MDR TB, so better infection control is recognized as important for control of MDR GNB. Improving hand hygiene, active surveillance, contact isolation for patients infected or colonized with MDR GNB, and enhanced environmental cleaning have been recommended by European and US agencies in order to reduce spread of MDR GNB in healthcare settings [85], [86], [87]. Implementation of such bundled interventions has reduced prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) in acute care hospitals and during outbreaks [39], [88]. For example, in 2007, when Israel was experiencing a nationwide carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae outbreak, the country's Ministry of Health implemented enhanced surveillance systems and infection control practices at hospitals and long term care facilities. A combination of sharing surveillance data among institutions, molecular characterization of strains, identification and isolation of carriers, cohorting of colonized patients and staffs, and active case finding, led to a 10-fold reduction in transmission of these strains [89], [90]. A similar approach has been used to control outbreaks of CRE in the US [39], [91]. Enhancing infection control in areas with high prevalence of MDR GNB is critical to controlling this epidemic, and has been emphasized by the WHO [92], [93].

Conclusions

There are striking similarities in the geographic regions (Fig. 1) and underlying health system deficiencies where both MDR TB and MDR GNB are prevalent. Many of the strategies used to approach MDR TB will also be needed to address the MDR GNB crisis (Table 1). Although MDR TB remains a serious public health problem, and major obstacles remain in global TB control, the availability of data describing the magnitude of the problem, the availability of new drugs and the global roll out of Xpert MTB/RIF have changed the landscape of TB control. The response to MDR TB, while not perfect, is as an example of how sufficient resources, combined with strong multinational and public-private partnerships, advocacy and political will, can positively impact global public health. This provides hope that the approaches to combating MDR GNB outlined in the Obama Administration's National Action Plan, may be effective.

Table 1.

Principles of TB control that can be applied to management of multidrug-resistant Gram negative bacilli (MDR GNB).

| 1. Raise awareness that MDR GNB are a public health problem that can affect anyone |

| 2. Implement and enforce robust antimicrobial stewardship interventions, especially in the private sector |

| 3. Implement and enforce robust infection control and prevention interventions in healthcare and long-term care facilities |

| 4. Create systems for surveillance and mandatory reporting of MDR GNB and facilitate appropriate responses by health departments |

| 5. Foster new drug development through partnerships between industry and academia |

| 6. Build political will to incentivize antibiotic and diagnostic test development through regulation |

| 7. Invest in and fast-track new drug development |

| 8. Encourage not-for-profit foundations and governments to support both basic science and translational research |

| 9. Support behavioral research to determine how to change the behaviors and attitudes of prescribers and patients in regard to antimicrobial use |

| 10. Enhance advocacy to raise awareness of MDR GNB and to encourage industry, funders and governments to support appropriate interventions |

We have learned from TB control efforts that along with innovations like new drugs and diagnostics, there will also need to be strategies to increase global laboratory capacity, make new drugs and diagnostics affordable for resource limited areas, provide good stewardship of new and existing antibiotics, improve surveillance systems and infection control efforts, and strengthen health systems in order to match increased diagnostic capacity with increased treatment capacity for MDR GNB infections.

We all play important roles in addressing the global MDR GNB problem (Table 1). Individual clinicians must practice good antimicrobial stewardship and encourage colleagues to prescribe antibiotics responsibly; infection control practitioners must design and enforce interventions that prevent MDR GN spread in healthcare facilities; public health officials must create and strengthen regional, national, and international surveillance systems for MDR GNB; and policy makers must foster international collaborations and partnerships among the scientific community, agriculture industry, pharmaceutical industry, regulators, not-for-profit organizations and policy makers, to tackle the global MDR GNB problem that is finally getting the attention it deserves.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2015. Global tuberculosis report. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Global tuberculosis. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/tb/topic/globaltb/default.htm. 2015 [accessed 28.09.15].

- 3.Grady D. The New York Times; 2015. Tuberculosis case prompts search for patient's fellow airline passengers. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . US Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2013. Antibiotic resistance threats in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brumfield B. CNN; 2015. Understanding CRE, the nightmare superbug that contributed to 2 deaths in L.A. February 19, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eisler P. Gannett Company; Charlottesville, VA: 2015. Deadly "superbugs" invade U.S. health care facilities. USA today. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Executive Office of the President of the United States . Executive Office of the President of the United States; 2014. Report to the president on combating antimicrobial resistance. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hampton T. Novel programs and discoveries aim to combat antibiotic resistance. JAMA. 2015;313:2411–2413. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson JR, Tchesnokova V, Johnston B, Clabots C, Roberts PL, Billig M. Abrupt emergence of a single dominant multidrug-resistant strain of Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 2013;207:919–928. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao S, Rama P, Gurushanthappa V, Manipura R, Srinivasan K. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae: a multi-centric study across Karnataka. J Lab Physicians. 2014;6:7–13. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.129083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lew KY, Ng TM, Tan M, Tan SH, Lew EL, Ling LM. Safety and clinical outcomes of carbapenem de-escalation as part of an antimicrobial stewardship programme in an ESBL-endemic setting. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2015;70:1219–1225. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deshpande P, Shetty A, Kapadia F, Hedge A, Soman R, Rodrigues C. New Delhi metallo 1: have carbapenems met their doom? Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51:1222. doi: 10.1086/656921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Molton J, Tambyah P, Ang B, Ling M, Fisher D. The global spread of healthcare-associated multidrug-resistant bacteria: a perspective from Asia. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1310–1318. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sidjabat H, Paterson D. Multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli in Asia: epidemiology and management. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2015;13:575–591. doi: 10.1586/14787210.2015.1028365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perez F, Villegas M. The role of surveillance systems in confronting the global crisis of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2015;28:375–383. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumarasamy KK, Toleman MA, Walsh TR, Bagaria J, Butt F, Balakrishnan R. Emergence of new antibiotic resistance mechanism in India, Pakistan, and the UK: a molecular, biological,a nd epidemiological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:597–602. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70143-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Diwan V, Chandran S, Tamhankar A, Lundborg CS, Macaden R. Identification of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase and quinolone resistance genes in Escherichia coli isolated from hospital wastewater from central India. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:857–859. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasoo S, Madigan T, Cunningham SA, Mandrekar JN, Porter SB, Johnston B. Prevalence of rectal colonization with multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae among international patients hospitalized at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:182–186. doi: 10.1086/674853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rogers B, Sidjabat H, Paterson D. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1–14. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae containing New Delhi metallo-beta-lactamase in two patients – Rhode Island, March 2012. MMWR. 2012;61:446–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Penders J, Stobberingh EE, Oude Lashof AM, Hoebe CJ, Savelkoul PH. High rates of antimicrobial drug resistance gene acquisition after international travel, The Netherlands. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:649–657. doi: 10.3201/eid2004.131718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tangden T, Cars O, Melhus A, Lowdin E. Foreign travel is a major risk factor for colonization with Escherichia coli producing CTX-M-type extended spectrum beta-lactamases: A prospective study with Swedish volunteers. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3564–3568. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00220-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guh AY, Bulens SN, Mu Y, Jacob JT, Reno J, Scott J. Epidemiology of Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in 7 US Communities, 2012–2013. JAMA. 2015;314:1479–1487. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akova M, Daikos G, Tsouvelekis L, Carmeli Y. Interventional strategies and current clinical experience with carbapenemase-producing Gram-negative bacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:439–448. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2012.03823.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Biehle LR, Cottreau JM, Thompson DJ, Filipek RL, O'Donnell JN, Lasco TM. Outcomes and Risk Factors For Mortality Among Patients Treated with carbapenems for Klebsiella spp. bacteremia. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Center for Disease Dynamics Economics, and Policy . Center for Disease Dynamics Economics, and Policy; Washington, D.C.: 2015. State of the world's antibiotics, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Das J, Holla A, Das V, Mohanan M, Tabak D, Chan B. In urban and rural India, a standardized patient study showed low levels of provider training and huge quality gaps. Health Aff. 2012;31:2774–2784. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Satyanarayana S, Subbaraman R, Shete P, Gore G, Shete P, Gore G, Das J, Cattamanchi A. Quality of tuberculosis care in India: a systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2015;19:751–763. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.15.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Caminero J. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: epidemiology, risk factors, and case finding. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:382–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nardell E, Dharmadhikari A. Turning off the spigot: reducing drug-resistant tuberculosis transmission in resource-limited settings. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2010;14:1233–1243. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gandhi NR, Weissman D, Moodley P, Ramathal M, Elson I, Kreiswirth BN. Nosocomial transmission of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in a rural hospital in South Africa. J Infect Dis. 2006;207:9–17. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Daneman N, Gruneir A, Bronskill SE, Newman A, Fischer HD, Rochon PA. Prolonged antibiotic treatment in long-term care: role of the prescriber. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:673–682. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kronman M, Zhou C, Mangione-Smith R. Bacterial prevalence and antimicrobial prescribing trends for acute respiratory tract infections. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e956–e965. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Das J, Kwan A, Daniels B, Satyanarayana S, Subbaraman R, Bergkvist S. Use of standardised patients to assess quality of tuberculosis care: a pilot, cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(11):1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00077-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohanan M, Vera-Hernández M, Das V, Giardili S, Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Rabin TL. The know-do gap in quality of health care for childhood diarrhea and pneumonia in rural India. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:349–357. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.3445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dutil L, Irwin R, Finley R, Ng LK, Avery B, Boerlin P. Ceftiofur resistance in Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg from chicken meat and humans, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:48–54. doi: 10.3201/eid1601.090729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lerner A, Adler A, Abu-Hanna J, Percia SC, Matalon MK, Carmeli Y. Spread of KPC-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: the importance of super-spreaders and rectal KPC concentration. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21:470.e1–470.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2014.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adler A, Baraniak A, Izdebski R, Fiett J, Salvia A, Samso JV. A multinational study of colonization with extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in healthcare personnel and family members of carrier patients hospitalized in rehabilitation centres. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O516–O523. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munoz-Price LS, Hayden MK, Lolans K, Won S, Calvert K, Lin M. Successful control of an outbreak of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae at a long-term acute care hospital. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:341–347. doi: 10.1086/651097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Palmore T, Henderson D. Managing transmission of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in healthcare settings: a view from the trenches. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1593–1599. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ben-David D, Maor Y, Keller N, Regev-Yochay G, Tal I, Shachar D. Potential role of active surveillance in the control of a hospital-wide outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae infection. Infect Cont Hosp Epid. 2010;31:620–626. doi: 10.1086/652528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Macaraig M, Burzynski J, Varma J. Tuberculosis control in New York City – a changing landscape. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2362–2365. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1402147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frieden T, Fujiwara P, Washko R, Hamburg M. Tuberculosis in New York City – turning the tide. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:229–233. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199507273330406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brudney K, Dobkin J. Resurgent tuberculosis in New York City – human immunodeficiency virus, homelessness, and the decline of tuberculosis control programs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:745–749. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.4.745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dellit TH, Owens RC, McGowan JE, Jr, Gerding DN, Weinstein RA, Burke JP. Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America guidelines for developing an institutional program for enhancing antimicrobial stewardship. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:159–177. doi: 10.1086/510393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Seddon JA, Hesseling AC, Marais BJ, McIlleron H, Peloquin CA, Donald PR. Paediatric use of second-line anti-tuberculosis agents: a review. Tuberculosis. 2012;92:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stop TB partnership. Available at: http://www.stoptb.org/. 2015 [accessed 29.09.15].

- 48.Weis SE, Slocum PC, Blais FX, King B, Nunn M, Matney GB. The effect of directly observed therapy on the rates of drug resistance and relapse in tuberculosis. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1179–1184. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404283301702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pai M, Dewan P. Testing and treating the missing millions with tuberculosis. PLoS Med. 2015;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Thoracic Society; CDC; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of tuberculosis, MMWR. 2003;52:1–77. [Google Scholar]

- 51.World Health Organization . Geneva WHO Press; 2010. Treatment of tuberculosis guidelines. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mase S, Chorba T, Lobue P, Castro K. Provisional CDC guidelines for the use and safety monitoring of Bedaquiliine fumarate (Sirturo) for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. MMWR. 2013;62:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mdluli K, Kaneko T, Upton A. The tuberculosis drug discovery and development pipeline and emerging drug targets. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2015;5 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shinnick T, Starks A, Alexander H, Castro K. Evaluation of the Cepheid Xpert MTB/RIF assay. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15:9–22. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.976556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Telenti A, Imboden P, Marchesi F, Lowrie D, Cole S, Colston MJ. Detection of rifampicin-resistance mutations in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Lancet. 1993;341:647–650. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90417-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Piatek AS, M VanCleeff, Alexander H, Coggin WL, Rehr M, Van Kampen S. GeneXpert for TB diagnosis: planned and purposeful implementation. Glob Health Sci Pract. 2013;1:18–23. doi: 10.9745/GHSP-D-12-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weyer K, Mirzayev F, Migliori GB, Van Gemert W, D'Ambrosio L, Zignol M. Rapid molecular TB diagnosis: evidence, policy making and global implementation of Xpert MTB/RIF. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:252–271. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00157212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2011. Automated real-time nucleic acid amplification technology for rapid and simultaneous detection of tuberculosis and rifampicin resistance: Xpert MTB/RIF system. Policy statement. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Global tuberculosis report 2014. World Health Organization. Geneva, 2014.

- 60.WHO . WHO; Geneva: 2015. WHO monitoring of Xpert MTB/RIF roll-out. [Google Scholar]

- 61.McAlister A, Driscoll J, Metchock B. DNA sequencing for confirmation of rifampin resistance detected by Cepheid Xpert MTB/RIF assay. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:1752–1753. doi: 10.1128/JCM.03433-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McNerney R, Zumla A. Impact of the Xpert MTB/RIF diagnostic test for tuberculosis in countries with a high burden of disease. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21:304–308. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.USAID . USAID; 2012. Press release: public–private partnership announces immediate 40 percent cost reduction for rapid TB test. August 6, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Central TB Division, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

- 65.Dlamini-Mvelase N, Werner L, Phili R, Cele L, Mlisana K. Effects of introducing Xpert MTB/RIF test on multi-drug resistant tuberculosis diagnosis in KwaZulu-Natal South Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:442. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pai M. The end TB strategy: India can blaze the trail. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141:259–262. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.156536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shewade HD, Govindarajan S, Sharath BN, Tripathy JP, Chinnakali P, Kumar AM. MDR TB screening in a setting with molecular diagnostic techniques: who got tested, who didn't and why? Public Health Action. 2015;5:132–139. doi: 10.5588/pha.14.0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Pai M, Yadav P, Anupindi R. Tuberculosis control needs a complete and patient-centric solution. Lancet. 2014;2:e189–e190. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70198-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Auld SC, Moore BK, Killam WP, Eng B, Nong K, Pevzner EC. Rollout of Xpert(®) MTB/RIF in Northwest Cambodia for the diagnosis of tuberculosis among PLHA. Public Health Action. 2014;21:216–221. doi: 10.5588/pha.14.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dominique JK, Ortiz-Osorno AA, Fitzgibbon J, Gnanashanmugam D, Gilpin C, Tucker T. Implementation of HIV and tuberculosis diagnostics: the importance of context. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(S3):S119–S125. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Food and Drug Administration, Sirturo (bedaquiline) product insert. Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD; 2012.

- 72.European Medicines Agency . European Medicines Agency; 2013. Deltyba (delamanid) [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jereb JA, Goldberg S, Powell K, Villarino M, LoBue P. Recommendations for use of an isoniazid-rifapentine regimen with direct observation to treat latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. MMWR. 2011;60:1650–1653. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Basu S, Andrews JR, Poolman EM, Gandhi NR, Shah NS, Moll A. Prevention of nosocomial transmission of extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis in rural South African district hospitals: an epidemiological modelling study. Lancet. 2007;370:1500–1507. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61636-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidelines for preventing the transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in health-care settings, 2005. MMWR. 2005;54:1–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2009. WHO policy on TB infection control in health care facilities, congregate settings and households. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brust JC, Shah NS, Scott M, Chaiyachati K, Lygizos M, van der Merwe TL. Integrated, home-based treatment for MDR-TB and HIV in rural South Africa: an alternate model of care. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2012;16:998–1004. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mitnick C, Bayona J, Palacios E, Shin S, Furin J, Alcántara F. Community-based therapy for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis in Lima, Peru. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:119–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wandwalo E, Makundi E, Hasler T, Morkve O. Acceptability of community and health facility-based directly observed treatment of tuberculosis in Tanzanian urban setting. Health Policy. 2006;78:284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.White House . White House; Washington, D.C.: 2015. National action plan for combating antibiotic-resistant bacteria. https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/docs/national_action_plan_for_combating_antibotic-resistant_bacteria.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Feinstein D. U.S. Senate; 2013. Preventing antibiotic resistance act: 1256. [Google Scholar]

- 82.U.S. House of Representatives . U.S. House of Representatives; 2011. Generating antibiotic incentives now act: 2182. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hatch O, Bennet B. U.S. Senate; 2014. PATH act: 2996. [Google Scholar]

- 84.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Tacconelli E, Cataldo MA, Dancer SJ, De Angelis G, Falcone M, Frank U. ESCMID guidelines for the management of the infection control measures to reduce transmission of multidrug-resistant Gram negative bacteria in hospitalized patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:1–55. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Siegel J, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, HICPAC Committee . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2006. Management of multidrug-resistant organisms in healthcare settings. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Guidance for control of infections with carbapenem-resistant or carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in acute care facilities. MMWR. 2009;58:256–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ben-David D, Masarwa S, Adler A, Mishali H, Carmeli Y, Schwaber M. A national intervention to prevent the spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Israeli post-acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:802–809. doi: 10.1086/676876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Schwaber M, Carmeli Y. An ongoing national intervention to contain the spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:697–703. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ben-David D, Mawarwa S, Adler A. A national intervention to prevent the spread of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in Israeli postacute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:802–809. doi: 10.1086/676876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hayden MK, Lin MY, Lolans K, Weiner S, Blom D, Moore NM. Prevention of colonization and infection by Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in long-term acute-care hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1153–1161. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu1173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Seto W, Otaiza F, Pessoa-Silva C,, World Health Organizatrion Core components for infection prevention and control programs: a World Health Organization network report. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31:948–950. doi: 10.1086/655833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pittet D, Allegranzi B, Storr S, Bagheri Nejad S, Dziekan G, Leotsakos A. Infection control as a major World Health Organization priority for developing countries. J Hosp Infect. 2008;68:285–292. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2007.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]