Abstract

Aims

We observed a microvascular structure in the cerebral cortex that has not, to our knowledge, been previously described. We have termed the structure a ‘raspberry’, referring to its appearance under a bright‐field microscope. We hypothesized that raspberries form through angiogenesis due to some form of brain ischaemia or hypoperfusion. The aims of this study were to quantify raspberry frequency within the cerebral cortex according to diagnosis (vascular dementia, Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration and nondemented controls) and brain regions (frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortices, regardless of diagnosis).

Materials and methods

In each of 10 age‐matched subjects per group, a 20‐mm section of the cerebral cortex was examined in haematoxylin‐and‐eosin‐stained sections of the frontal, temporal and parietal, and/or occipital lobes. Tests were performed to validate the haematoxylin‐and‐eosin‐based identification of relative differences between the groups, and to investigate inter‐rater variability.

Results

Raspberry frequency was highest in subjects with vascular dementia, followed by those with frontotemporal lobar degeneration, Alzheimer's disease and last, nondemented controls. The frequency of raspberries in subjects with vascular dementia differed from that of all other groups at a statistically significant level. In the cerebral lobes, there was a statistically significant difference between the frontal and occipital cortices.

Conclusions

We believe the results support the hypothesis that raspberries are a sign of angiogenesis in the adult brain. It is pertinent to discuss possible proangiogenic stimuli, including brain ischaemia (such as mild hypoperfusion due to a combination of small vessel disease and transient hypotension), neuroinflammation and protein pathology.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease; brain ischaemia; frontotemporal lobar degeneration; neovascularization, pathologic; neovascularization, physiologic; vascular dementia

Introduction

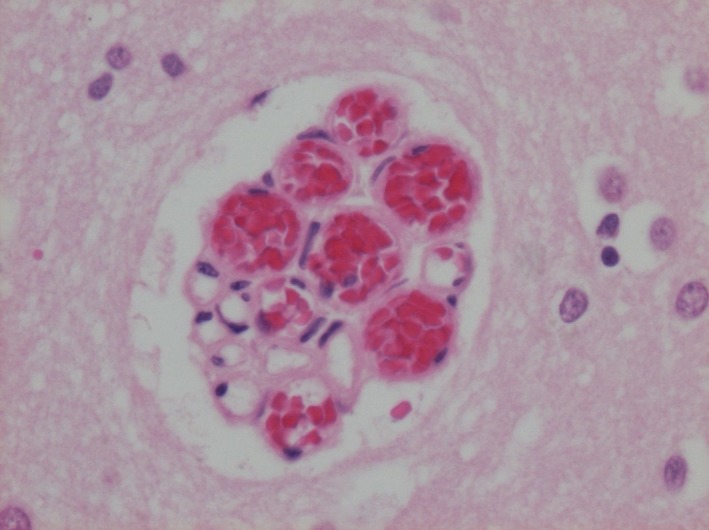

In several neuropathological autopsies, we observed a microvascular structure in the cerebral cortex that has not, to our knowledge, been previously described. We termed the structure a ‘raspberry’, referring to its appearance under a bright‐field microscope rather than making assumptions about its origin. A raspberry consists of a minimum of three (by our definition) microvascular lumen in immediate proximity to one another, sometimes surrounded by a small shrinkage artefact of the nearby tissue (Figure 1). The vessels are likely to be capillaries or precapillary arterioles. Raspberries have been observed in the cortex of all cerebral lobes and in various neuropathological diagnoses, including vascular dementia (VaD), Alzheimer's disease (AD), frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), Lewy body disease, vascular brain injury (VBI) without dementia and prion disease, as well as in cases with no apparent neuropathological disease. Raspberries have only rarely been observed in the subcortical grey matter and have not been detected in the white matter.

Figure 1.

A ‘raspberry’ in the cerebral cortex. Photomicrograph of a ‘raspberry’ in the cerebral cortex (parietal lobe), with a diameter of 80 × 65 μm. Stain: haematoxylin and eosin.

As structures composed of blood vessels, raspberries are likely formed through angiogenesis (the formation of new capillaries from already existing ones 1). Arteriogenesis (the development of smaller blood vessels into larger ones due to forces of blood flow 2) may also contribute.

In this study, we hypothesized that raspberries form as a side effect of angiogenesis in the adult brain. The vasculature of the adult brain is stable under normal conditions, but angiogenesis can be induced in response to noxious stimuli 3. Since one such stimulus is cerebral ischaemia 4, we expected the frequency of raspberries to differ between neuropathological diseases where greater or lesser ischaemia was presumed to occur during the course of the disease. To test our hypothesis, we quantified raspberries in age‐matched subjects with VaD, AD, FTLD and nondemented controls. We expected to find a higher raspberry frequency in VaD and AD compared to FTLD and controls due to VaD and AD's well‐known associations with cerebrovascular pathologies 5, 6, 7, 8.

Furthermore, we wanted to compare raspberry frequency between cerebral lobes. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has indicated that the frontal lobes are the most vulnerable to white matter disease (WMD) in the elderly 9. There are different forms of WMD, but the condition referred to here is frequently associated with cerebral small vessel disease (SVD) and is believed to result (at least partially) from ischaemia due to hypoperfusion 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13. Hypothesizing that the cortex follows the same pattern as the white matter, we expected to find more raspberries in the cortex of the frontal lobes than the others, regardless of diagnosis.

As such, our aims were to quantify raspberry frequency within the cerebral cortex according to diagnosis (VaD, AD, FTLD and nondemented controls) and brain regions (frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital cortices, regardless of diagnosis).

Materials and methods

Patient cohort

This was a retrospective study based on microscopic examination of tissue sections, autopsy reports and medical records of adult (age at death ≥18 years) patients who had undergone a diagnostic neuropathological examination at the clinical department of Pathology in Lund, Sweden, during the period of January 2009–September 2018. Data from autopsy reports was accessed through Sympathy, a digital database where all findings from autopsies performed in Lund are recorded. Data from medical records were accessed through the digital medical record system Melior. Subjects with VaD, AD and FTLD were included based on a combination of a pure (not mixed) neuropathological diagnosis and clinically diagnosed cognitive disorder/dementia. Controls were included based on absence of significant neuropathological findings that would correspond to a cognitive disorder, in combination with absence of clinical dementia. All diagnostic work was carried out prior to this study; thus, no neuropathological disease categorization was performed. All groups were of similar age. Full criteria are detailed below.

Histopathological procedure

The diagnostic neuropathological examination procedure has been described in detail 14. Briefly, the entire brain was fixed in formaldehyde for several weeks. Slices cut from the cerebrum, cerebellum and brain stem were examined macroscopically, followed by selection of coronal slices and smaller tissue blocks for dehydration and paraffin embedding. All slices were cut into sections, 6 micrometres thin. Routine stains included haematoxylin and eosin (H&E); Luxol fast blue for myelin; Campbell and Gallyas silver stains for neuritic plaques, neurofibrillary tangles and neurites and alkaline Congo red for amyloid. Additional stains were used when indicated.

Neuropathological diagnosis of VaD, AD and FTLD

Vascular dementia was diagnosed based on a combination of extensive cerebrovascular pathology and VBI in the absence of significant protein pathology, in individuals with clinically diagnosed dementia. Vascular brain injuries considered included infarcts of various sizes (large, lacunar and microscopic), haemorrhages, diffuse WMD, cribriform deep grey matter and neuronal loss or atrophy in the absence of protein pathology 5, 6, 7, 8, 15, 16.

Alzheimer's disease was diagnosed based on the 1997 NIA‐Reagan consensus criteria and the 2012 NIA‐AA update, where beta‐amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles, the neuropathological hallmarks of AD, are required for diagnosis 17, 18. The criteria grade the severity of AD neuropathology based on the Thal plaque phase, Braak stage and CERAD score for neuritic plaques 19, 20, 21, 22. As a minor modification of the criteria, the degree of neuronal loss, neurites and glial activation was also considered.

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration is the neuropathological equivalent of frontotemporal dementias (FTDs) and a group of cognitive disorders with behavioural and movement manifestations. Neuropathologically, the diseases are characterized to a large extent by inclusions of tau protein, transactive response DNA binding protein 43 (TDP‐43) or fused in sarcoma protein. FTLD was diagnosed based on published consensus criteria and nomenclature 23, 24, 25.

Subjects

The following inclusion criterion was applied to all subjects: access to ≥1 section from the frontal lobes (taken from the frontal pole), ≥1 section from the temporal lobes (taken from the medial temporal lobe) and ≥1 section from the parietal and/or occipital lobes (taken from various regions).

For the VaD, AD and FTLD groups, the following additional inclusion criteria were applied: clinical dementia (diagnosed by a specialist in cognitive medicine or neurology or by a general practitioner), a pure neuropathological diagnosis (thus excluding mixed dementias) and a sufficiently extensive neuropathological investigation (defined as ≥1 bihemispheric coronal section and ≥5 sections from different brain regions). The clinical dementia criterion was applied to ensure that the neuropathological diagnosis had been clinically significant.

For the control group, the following additional inclusion criteria were applied: absence of clinically diagnosed dementia or symptoms indicating dementia reported in the medical records, absence of significant major neuropathology, a neuropathological examination above a minimum level of extension (≥5 sections from different brain regions) and age at death ≥65 years. The age criterion was applied to ensure adequate age‐matching with demented subjects (see below).

As stated, nondemented controls were not allowed to have any significant neuropathology and demented subjects with mixed dementia were excluded. However, some minor co‐occurrent pathology was allowed, since the pathologies in question were not believed to be extensive or long‐lasting enough to significantly affect raspberry formation. Based on the literature and our own appraisal, the following co‐occurrent neuropathologies were allowed in all subjects: Braak stage I–II, primary age‐related tauopathy (PART), a total of 1–2 cerebral microinfarcts or lacunar infarcts, other minor signs of ischaemia (mildly cribriform deep grey matter) and acute or subacute cardiac arrest encephalopathy (CAE) [ischaemic damage due to cardiac arrest with transient return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC)] 18, 26, 27, 28.

A total of 83 individuals met the above‐mentioned criteria (VaD = 19, AD = 21, FTLD = 25, control = 18), and an approximate age‐matching was performed until 10 subjects per group had been selected. An age difference of ≤5 years was considered matched.

Raspberry quantification

Raspberries were counted manually in H&E‐stained sections. The quantification was based on one section per subject from the following regions: the frontal cortex (frontal pole), temporal cortex (medial temporal lobe), parietal cortex (various regions) and/or occipital cortex (various regions), resulting in 3–4 examined sections per subject (there were missing sections of the parietal or occipital cortex in some cases). In each section, a distance of 20 mm was measured and marked at the surface of the cortex. Under the marked distance, the entirety of the cortex was examined with a bright‐field microscope using a × 10 magnification. When a possible raspberry was identified, it was examined using a × 40 magnification before being included or excluded. Structures with two lumen were also noted, but not defined as raspberries. To increase the specificity, only structures where the lumen were transversally sectioned were included, since longitudinally sectioned structures would be less characteristic and more difficult to define objectively. For each raspberry, its number of lumen was noted.

Control staining and control counting

To validate the identification of relative differences between the groups with H&E, 16/151 sections (10.5% of all included sections) were randomly selected to be immunohistochemically stained for collagen IV. The raspberries were then quantified in areas equivalent to those of the corresponding H&E‐stained sections. Collagen IV is a constituent of the basal lamina, so staining for it makes the identification of vascular structures easier. We thus expected to find considerably more raspberries here than in the H&E‐stained sections, but also expected any relative differences between the groups to remain the same.

To test for inter‐rater variability, all included sections of the frontal lobes (n = 40, 26.5% of all included sections) were independently examined by an experienced neuropathologist and the results were compared.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM spss Statistics 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). When comparing the raspberry frequency between VaD, AD, FTLD and controls, subjects were represented by the mean raspberry frequency of the examined sections, since the number of examined sections varied (between 3 and 4 sections per subject). The Kruskal–Wallis test was run to test for statistical significance between any of the groups, followed by the Mann–Whitney test for pairwise testing. When comparing the raspberry frequency between the cortices of the cerebral lobes, the Friedman test was run to test for significance between any of the lobes, followed by the Wilcoxon signed ranks test for pairwise testing. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant for the Kruskal–Wallis and Friedman tests. Six pairwise tests, either Mann–Whitney or Wilcoxon signed ranks, were run. We therefore applied a Bonferroni correction, resulting in an adjusted level of significance of P = ≤0.008 for these tests (0.05/6). In the following sections the raspberry median (min–max) is presented, using the unit of raspberries/cm cortex.

Results

Subjects

Demographic data are presented in Table 1. As shown in the table, the groups were of similar age. In the FTLD group, there were five patients with tauopathy and five patients with TDP‐43 proteinopathy. The prevalence of co‐occurrent neuropathologies is presented in Table 2. Of these, ischaemia‐related pathologies were the most frequent: 1–2 cerebral microinfarcts or lacunar infarcts were present in one subject with AD and three controls; mildly cribriform deep grey matter was present in two subjects with AD, three subjects with FTLD and one control; and ischaemia related to CAE occurred in two controls (subjects died <1 h and <2 weeks after ROSC respectively). In addition, Braak stage I–II was present in one subject with VaD and one subject with FTLD.

Table 1.

Demographic variables

| Group | Sex (F/M) | Age at death (year)* | Duration of dementia (year)* |

|---|---|---|---|

| VaD | 5/5 | 78.5 (71–86) | 4 (1–8) |

| AD | 6/4 | 76.5 (70–87) | 6.5 (4–12) |

| FTLD† | 5/5 | 78 (71–85) | 4.5 (2–20) |

| Control | 3/7 | 76.5 (69–84) | n/a |

AD, Alzheimer's disease; F, female; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; M, male; TDP‐43, transactive response DNA‐binding protein 43; VaD, vascular dementia.

*Median (min–max).

†The FTLD group consisted of five patients with TDP‐43 pathology and five patients with tau pathology.

Table 2.

Co‐occurrent neuropathology

| Neuropathology | VaD (Y/N) | AD (Y/N) | FTLD (Y/N) | Control (Y/N) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–2 small infarcts* | n/a | 1/9 | 0/10 | 3/7 |

| CAE | 0/10 | 0/10 | 0/10 | 2/8 |

| Ischaemia, other† | n/a | 0/10 | 3/7 | 1/9 |

| Braak I–II | 1/9 | n/a | 1/9 | 0/10 |

| PART | 0/10 | n/a | n/a | 0/10 |

AD, Alzheimer's disease; CAE, cardiac arrest encephalopathy; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; N, no; PART, primary age‐related tauopathy; VaD, vascular dementia; Y, yes.

*Cerebral microinfarcts or lacunar infarcts.

†Mild cribriform changes in the deep grey matter.

Raspberry quantification: general remarks

Sections representing the cortex of all four lobes were present in 31/40 cases. The frontal and temporal lobes were represented in all subjects. A section of the parietal lobe was lacking in two subjects from the VaD group, and a section of the occipital lobe was lacking in three subjects from the VaD group and four subjects from the control group. A total of 560 raspberries were counted in 151 sections, corresponding to an overall 1.9 raspberries/cm cortex, with substantial variation between and within groups (see below). At least one raspberry was found in 39/40 cases (0 raspberries were found in 1 control). Raspberries were found throughout the cortex and in both pathologically affected and seemingly normal cortex. In several cases, the raspberries appeared to be focally clustered rather than diffusely distributed. The vessels comprising the raspberries were estimated to be capillaries or precapillary arterioles, though this was not further investigated.

Raspberries according to neuropathological diagnosis

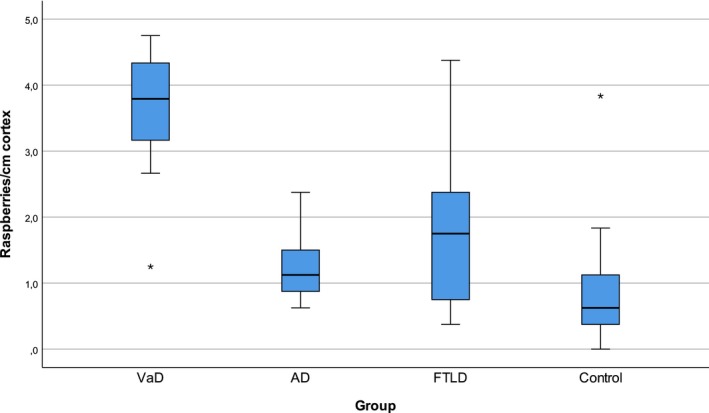

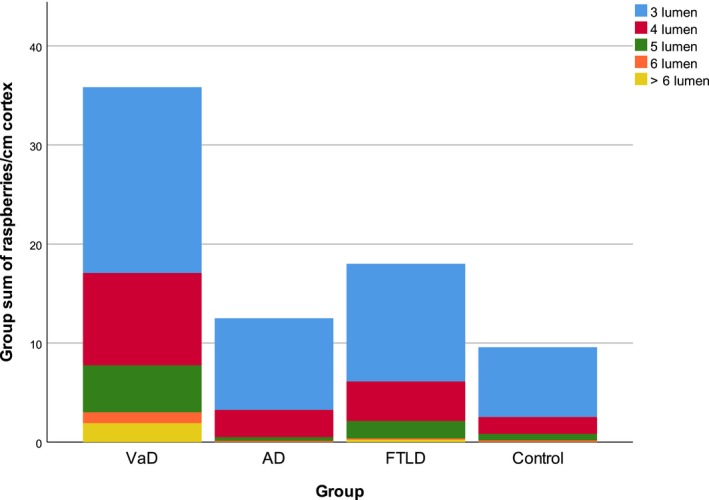

Raspberry frequency according to neuropathological diagnosis is demonstrated graphically in Figures 2 and 3. The highest raspberry frequency was found in the VaD group [3.8 (1.3–4.8) raspberries/cm cortex], followed by FTLD [1.8 (0.4–4.4) raspberries/cm cortex], AD [1.1 (0.6–2.4) raspberries/cm cortex] and last, nondemented controls [0.6 (0.0–3.8) raspberries/cm cortex]. When the one outlier of the control group was excluded, the frequency of this group was 0.6 (0.0–1.8) raspberries/cm cortex. This outlier had only minor neuropathological findings (one small cerebral infarct), although clinical findings of interest were described in the medical records; see Discussion.

Figure 2.

Raspberry frequency according to diagnosis. Raspberries/cm cortex in age‐matched subjects with VaD, AD, FTLD and nondemented controls. Outliers are represented by asterisks. AD, Alzheimer's disease; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; VaD, vascular dementia.

Figure 3.

Raspberry frequency according to diagnosis, with lumen‐based fractions. Group sum of raspberries/cm cortex, fractioned based on the number of raspberry lumen. AD, Alzheimer's disease; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; VaD, vascular dementia.

Since the Kruskal–Wallis test demonstrated statistically significant differences between the groups (P = <0.001), pairwise tests were run. These revealed statistically significant differences between VaD and all other groups (P = <0.001, P = 0.005 and P = <0.001 compared to AD, FTLD and controls respectively). Comparing AD and FTLD to controls resulted in low, but not statistically significant, P values (P = 0.07 for both). The difference between AD and FTLD was also not statistically significant (P = 0.54).

Raspberries according to cerebral lobes

Raspberry frequency according to cerebral lobes is presented in Table 3. When observing the median of all subjects, a small rostral‐to‐caudal tendency was observed, with a median of 1.5 (0.0–9.5) raspberries/cm cortex in the frontal lobe, 1.3 (0.0–8.0) raspberries/cm cortex in the temporal lobe, 1 (0.0–12.0) raspberries/cm cortex in the parietal lobe and 0.5 (0.0–4.0) raspberries/cm cortex in the occipital lobe. More raspberries were found in the frontal cortex than in the occipital cortex in all groups, while the differences between the other lobes were more heterogeneous. The Friedman test revealed statistically significant differences between the lobes (P = 0.005); as such, pairwise tests were run. These tests revealed a statistically significant difference between the frontal and occipital lobes (P = <0.001). The other differences did not demonstrate statistical significance after Bonferroni correction: P = 0.03 for frontal–temporal, P = 0.11 for frontal–parietal, P = 0.85 for temporal–parietal, P = 0.07 for temporal–occipital and P = 0.01 for parietal–occipital comparisons respectively.

Table 3.

Raspberry frequency according to brain regions

| Group | Frontal lobe | Temporal lobe | Parietal lobe | Occipital lobe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VaD | 5.8 (0.5–9.5) | 2.5 (1–8) | 3 (1–8) | 1.5 (0–3) |

| AD | 1.3 (0–4.5) | 1.5 (0–3) | 1 (0–4) | 0.5 (0–2) |

| FTLD | 2 (0.5–6) | 1 (0–3) | 0.5 (0–12) | 1.3 (0–4) |

| Control | 0.5 (0–9.5) | 0.5 (0–4) | 0.8 (0–1.5) | 0 (0–0.5) |

| Total | 1.5 (0–9.5) | 1.3 (0–8) | 1 (0–12) | 0.5 (0–4) |

Raspberries/cm cortex in the frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes. Values presented as median (min–max).

AD, Alzheimer's disease; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; VaD, vascular dementia.

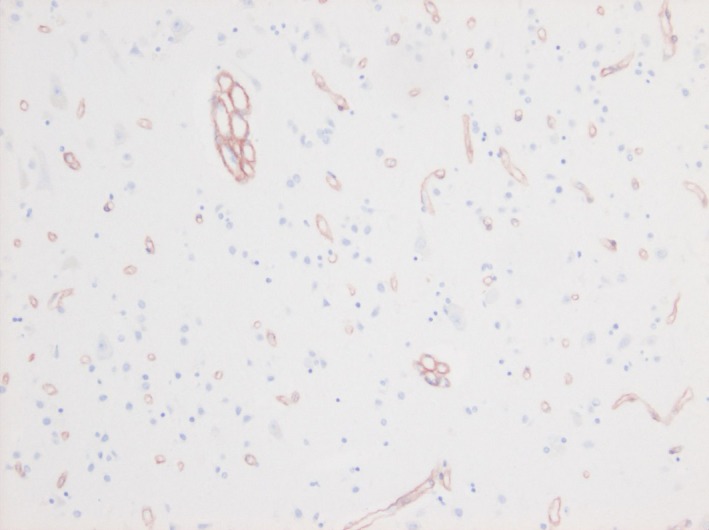

Control stain and control count

Raspberry frequency in sections stained for collagen IV and corresponding H&E‐stained sections is presented in Table 4. As expected, considerably more raspberries were identified in sections stained for collagen IV than those stained with H&E (a difference of 0–10 raspberries/cm cortex compared to H&E‐stained sections). However, when comparing the raspberry frequency between VaD, AD, FTLD and controls using the collagen‐IV‐based values, the relative differences between the groups were the same as in the corresponding H&E‐stained sections. It should be noted that the stains were not applied to serial sections, which may explain the large range of differences between corresponding sections. Raspberries in a section stained for collagen IV are shown in Figure 4.

Table 4.

Control stain

| Group | H&E* | Collagen IV* | Relative change, %† | Absolute change† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VaD | 3 (1.5–9.5) | 10.8 (1.5–13) | 260 | 7.8 |

| AD | 2.3 (0–3) | 5.5 (1.5–10) | 130 | 3.2 |

| FTLD | 1.3 (0–3) | 3.8 (1.5–7) | 190 | 2.5 |

| Control | 0.3 (0–4) | 2.5 (0–7) | 730 | 2.2 |

Raspberry frequency in corresponding sections stained with H&E and immunohistochemistry for collagen IV. Data based on four randomly selected sections per group. Values are presented in raspberries/cm cortex unless otherwise indicated.

AD, Alzheimer's disease; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; H&E, haematoxylin and eosin; VaD, vascular dementia.

*Median (min–max).

†Compared to the median.

Figure 4.

Cortical raspberries in a section stained for collagen IV. Photomicrograph of two raspberries and an abundance of normal 1‐luminal small blood vessels in a section of the cerebral cortex (occipital lobe) stained immunohistochemically for collagen IV.

The inter‐rater variability is presented graphically under Supporting Information. The highest variability was found in the VaD group, but both positive and negative differences were found in all groups. The overall variability ranged from −3 to 2 raspberries/cm cortex with a median of 0 (0.5 in absolute values). The difference was ≤±1 raspberry/cm cortex in 33/40 sections.

Summary

The raspberry frequency was higher in the VaD group than in all other groups, and the differences were statistically significant. The frequency was also higher in the AD and FTLD groups compared to controls, but these differences did not achieve statistical significance. Raspberry frequency was higher in the frontal lobes compared to the occipital lobes regardless of diagnosis, and the difference here was statistically significant.

Discussion

Raspberries and ischaemia

We hypothesized that raspberries are a sign of angiogenesis in the adult brain and, based on our hypothesis, expected to find a higher frequency of raspberries in brains presumably exposed to ischaemia during the course of the disease. Specifically, we expected raspberry frequency to be higher in VaD and AD compared to FTLD and controls due to VaD and AD's well‐known associations with cerebrovascular pathologies 5, 6, 7, 8. We believe that the statistically significant (P = <0.001) higher raspberry frequency in VaD compared to controls provides support for our hypothesis. The differences between AD and FTLD on one hand and controls on the other did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07 for both), although, with more subjects, they may have. In addition, the higher frequency of VBIs in the control group may have reduced the differences between these groups. These differences are, therefore, also discussed below.

The vasculature of the adult brain is stable under normal conditions, but angiogenesis can be induced in response noxious stimuli 3. In a state of ischaemia, hypoxia is thought to be the most important proangiogenic stimulus 29 by the induction of increased transcription of proangiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) 30. Complete, permanent, focal ischaemia with resulting infarcts is known to result in (mainly locally) increased levels of proangiogenic factors, increased capillary density and morphological signs of angiogenesis, both in animal experiments and in patients 29, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39. However, we frequently observed raspberries in seemingly normal cortex, and in one control (outlier) the raspberry frequency was surprisingly high, given the minor co‐occurrent neuropathology of just one small cerebral infarct. Considering this, we believe that a relatively minor ischaemic stimulus, such as transient and/or partial ischaemia (hypoperfusion), could be sufficient to induce raspberry formation. Also in these settings (transient focal ischaemia, chronic cerebral hypoperfusion), animal experiments have demonstrated proangiogenic factors and increased capillary density 34, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45. Furthermore, positron emission tomography has shown endothelial activation (suggestive of angiogenesis) in the hypoperfused hemisphere of patients with unilateral intracranial arterial stenosis 46.

Angiopathic or non‐Wallerian WMD can be considered a well‐established neuropathological finding suggestive of hypoperfusion. This form of WMD is believed to arise from SVD, and it has been associated with VaD, AD and Pick's disease (a tauopathy on the FTLD spectrum) 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 47. In addition to SVD, there are indications that low systemic blood pressure could contribute to ischaemic damage. Here, some clinical findings described in the medical records of the outlier individual in the control group deserve mentioning. Specifically, this subject suffered from marked and prolonged systemic hypotension (systolic blood pressure well below 100) and anaemia, documented on several occasions over at least a month prior to death. We propose that this could be a possible explanation for the subject's high raspberry frequency, since, as mentioned, the subject showed only modest co‐occurrent neuropathology. Previous studies suggest that hypotension, even transient, can affect the brain, likely through hypoperfusion and resulting ischaemia. A correlation has been demonstrated between hypotension and MRI‐verified WMD 48, 49, orthostatic hypotension is a risk factor for clinical dementia 50, and infarcts have been shown in the white and deep grey matter due to acute hypotension in a hereditary form of SVD, indicating synergistic activity between hypotension and SVD 51.

In the cerebral cortex, where our raspberry quantification took place, an equivalent of WMD (as a neuropathological finding suggestive of hypoperfusion) is not as well established. Regional atrophy of pyramidal cells without other characteristics of neurodegenerative disease has been described and associated with clinical dementia, and it has been proposed that the underlying cause is vascular 15. In addition, imaging studies have indicated a correlation between cortical thinning and WMD but have been criticized for not taking the possible co‐occurrence of neurodegenerative disease into account 52.

We propose that (frequent) raspberries could be suggestive of cortical hypoperfusion – perhaps in the form of recurrent hypotension, where SVD could contribute by rendering the blood vessels unable to respond to the hypotensive episodes, resulting in cerebral hypoperfusion. While this would manifest as WMD in the white matter, the capillary‐dense and well‐perfused cortex may remain relatively unharmed and respond with angiogenesis, of which raspberries could be a sign. Whether raspberries can form in small numbers also under physiological conditions remains to be determined.

Raspberries, neuroinflammation and protein pathology

Several studies have demonstrated signs of angiogenesis in AD (increased levels of proangiogenic factors, endothelial activation, morphological signs of angiogenesis and regionally increased capillary density) 53, 54, 55, 56, 57. Furthermore, there is a known potential proangiogenic stimulus in the form of ischaemia: nonstructural as well as structural effects on blood vessels may contribute to hypoperfusion in AD, the hypoperfusion thus mainly reflecting insufficient blood supply rather than the reduced metabolism of an atrophic brain 58, 59. On the FTLD spectrum, signs of angiogenesis (endothelial activation and increased capillary density) have been demonstrated in the deep grey matter and cerebral cortices of patients with progressive supranuclear palsy (a tauopathy) 60. However, while there is an association between SVD and WMD in Pick's disease 47, there is no well‐established association between ischaemia and FTLD. Given (at variance with our hypothesis) the higher raspberry frequency in FTLD compared to controls (P = 0.07), possible additional proangiogenic stimuli should be considered.

First, inflammation can induce angiogenesis via the release of cytokines with proinflammatory as well as proangiogenic effects 61. Considering the central nervous system, for example inflammation‐induced angiogenesis is a known phenomenon in multiple sclerosis 62. In neurodegenerative disease, a different form of inflammation is believed to take place, where traditional inflammatory cells are lacking and glia (mainly microglia) appear to play a central role 63, 64. This form of inflammation, too, involves increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines with known proangiogenic effects, as demonstrated in both AD and FTD 61, 65, 66, 67. It is possible, therefore, that the inflammation associated with neurodegenerative disease contributes to angiogenesis, and thus to raspberry formation.

Second, the protein pathology of neurodegenerative disease may play a direct role in angiogenesis. Studies have shown interactions between beta‐amyloid and proteins with angiogenic effects. The results indicate proangiogenic as well as antiangiogenic effects 55, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72. On one hand, beta‐amyloid causes proangiogenic activity by enhancing the effect and increasing the expression of basic fibroblast growth factor (a proangiogenic factor) 70, 71. On the other hand, VEGF binds to beta‐amyloid with high affinity, which may have an antiangiogenic influence by preventing VEGF from binding to its receptors 55. In addition, beta‐amyloid can bind to a VEGF‐receptor and exert a competitive antagonism 72. The net effect of beta‐amyloid appears to be concentration‐dependent, where low concentrations are proangiogenic while higher concentrations are antiangiogenic 71. This could mean that the net effect is antiangiogenic in a brain with AD, thus lowering the probability that direct interactions between beta‐amyloid and angiogenic proteins contribute to raspberry formation. Whether the abnormal proteins of FTLD possess any corresponding angiogenic effects is un‐known.

In summary, it is possible that stimuli other than ischaemia could also contribute to angiogenesis, and thus to raspberry formation.

Raspberries in relation to cerebral lobes

More raspberries were present in the frontal cortex than the occipital cortex in all groups, and the difference was statistically significant (P = <0.001). This could indicate that at least part of the raspberry formation occurs due to a mechanism common to all groups. Our results correspond to previous studies of AD and a hereditary form of SVD, where it is described that the WMD is the most severe in the frontal lobes 11, 12, 73. Furthermore, in a cohort of elderly subjects, MRI findings indicated that the frontal lobes are the first to be affected by WMD 9. It has been suggested that the longer end arteries that supply the white matter of the frontal lobes makes it more vulnerable to hypoperfusion and thus WMD 9. This explanation is not as easily applied to the cortex, although there may be a link. MRI has shown a correlation between lacunar infarcts in the white matter and focal thinning of the overlying cortex in a hereditary form of SVD, thus demonstrating cortical damage secondary to ischaemia in the white matter 74. Perhaps white matter hypoperfusion, and a resulting ischaemic environment for oligodendrocytes and axons, can render the overlying neurons themselves more susceptible to ischaemia, thus decreasing their threshold for releasing proangiogenic factors. Alternatively, given the inflammatory response to neuronal damage 75, it is possible that cortical neuronal degradation secondary to WMD induces inflammation in the cortex, thereby resulting in a more proangiogenic environment.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this study were the access to complete autopsy reports and clinical data, the neuropathologically verified pure diagnoses, the use of age‐matched subjects and an extensive amount of data. There are several limitations, which should also be recognized.

First, as a retrospective study, examinations were based on available data and material rather than gathered specifically for this study. This resulted in the absence of tissue sections in some subjects and the fact that the exact locations of the parietal and occipital lobes were varying.

Second, there was some co‐occurrent neuropathology in all groups, the most prominent one being ischaemia. This may explain some of the raspberry burden in the control group, and it is possible that it reduced the difference between AD and FTLD on one hand, and controls on the other. Then again, a control group with a certain amount of pathology may be more representative of the general population.

Third, a vessel‐specific stain was not used. As could be expected, the immunohistochemical staining for collagen IV revealed considerably more raspberries than H&E staining. Since the sections stained with H&E and for collagen IV were not serially cut, conclusions about the considerable range of differences cannot be made. The results indicate that staining for collagen IV would have been superior to H&E staining for an absolute quantification. We do, however, believe that our observed relative differences hold true, since the relative rating of the groups was the same using both stains.

Fourth, the study was not blinded regarding neuropathological diagnosis. Even with blinding, the underlying neuropathology would likely have been recognized in some cases. To compensate for this, 40/151 sections were counted by two investigators, who were blinded to the results of the other. The results indicated some degree of inter‐rater variability, which was largest in the VaD group, but they did not indicate systematic over‐ or underrating for any of the groups. The variability does, however, indicate that differences within the groups may have been less reliable if tested. This may also indicate that determining the presence of raspberries is still, to some extent, a question of judgement, despite the attempt at an objective definition.

Finally, the method of quantifying raspberries should be addressed. Raspberries with few lumen may, in fact, be different structures to those with many lumen, even though the relative differences between these types mimicked those of the total raspberry load. We counted only transversally sectioned raspberries (thus potentially excluding raspberries with different orientations, for example others than parallel to the surface of the cortex), again emphasizing that the current method does not provide a reliable absolute quantification of raspberries. Our observation that raspberries often appear focally rather than diffusely could make the current approach imprecise, as the random inclusion or exclusion of some foci may have affected the results. Perhaps a more systematic raspberry quantification in larger areas is necessary to identify weak but significant correlations. As well, we counted raspberries in an area based on a distance measured at the surface of the cortex. This may have introduced a random error, since the geometry of the gyri and sulci in the examined region affects the size of the area. It may also have introduced a systematic error, since the cortex would be expected to be thinner in demented individuals and, thus, the area would be expected to be smaller. However, this approach could also be considered a strength: if raspberries remain intact while the cortex degenerates, an area‐based unit of raspberry frequency would be falsely higher in degenerated regions.

Conclusion and future studies

This is, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to describe and examine the ‘raspberry’, a cortical microvascular structure. We demonstrated that raspberries were more frequent in VaD compared to AD, FTLD and controls, and observed a similar (but not statistically significant) tendency in AD and FTLD compared to controls. We also demonstrated that raspberries were more frequent in the frontal than the occipital cortex regardless of diagnosis. We hypothesize, therefore, that raspberries are formed through angiogenesis in the adult brain and propose that recurrent cortical ischaemia due to hypotensive episodes, in combination with SVD, could be an underlying stimulus. Other mechanisms, such as neuroinflammation and protein pathology, may also contribute. Further studies are necessary to evaluate this hypothesis. Such studies could aim to examine correlations between raspberry frequency and SVD, WMD and clinical hypotension. Furthermore, the blood vessels that compose a raspberry should be examined for signs of active angiogenesis, and the vessel type should be determined. An investigation into the fate of individual blood vessels by reconstruction of serial sections would also be pertinent.

Author contributions

HO carried out subject inclusion, raspberry quantification, statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. EE designed the study, carried out control counting of raspberries, supervised the project and cowrote the manuscript.

Ethics

The study was given a favourable judgement by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund (Dnr 2018/1143, Dnr 2019–00080).

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Inter‐rater variability. Bland Altman diagram demonstrating the inter‐rater variability of raspberries/cm cortex in the frontal cortex. The x‐axis demonstrates the mean values of the investigators. The y‐axis represents the differences between the investigators. AD, Alzheimer's disease; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; VaD, vascular dementia.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Susann Ullén for expert consulting and the Trolle‐Wachtmeister Foundation for Medical Research for essential funding of this study.

Ek Olofsson H. and Englund E. (2019) Neuropathology and Applied Neurobiology 45, 557–569 A cortical microvascular structure in vascular dementia, Alzheimer's disease, frontotemporal lobar degeneration and nondemented controls: a sign of angiogenesis due to brain ischaemia?

References

- 1. Risau W. Mechanisms of angiogenesis. Nature 1997; 386: 671–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Cai W, Schaper W. Mechanisms of arteriogenesis. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin 2008; 40: 681–92 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Plate KH. Mechanisms of angiogenesis in the brain. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1999; 58: 313–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beck H, Plate KH. Angiogenesis after cerebral ischemia. Acta Neuropathol 2009; 117: 481–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grinberg LT, Thal DR. Vascular pathology in the aged human brain. Acta Neuropathol 2010; 119: 277–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Thal DR, Grinberg LT, Attems J. Vascular dementia: different forms of vessel disorders contribute to the development of dementia in the elderly brain. Exp Gerontol 2012; 47: 816–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lowe J, Kalaria R. Dementia In Greenfield's Neuropathology. Eds Love S, Budka H, Ironside J, Perry A. New York: CRC Press, 2015; 858–973 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kalaria RN. The pathology and pathophysiology of vascular dementia. Neuropharmacology 2018; 134(Pt B): 226–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Artero S, Tiemeier H, Prins ND, Sabatier R, Breteler MM, Ritchie K. Neuroanatomical localisation and clinical correlates of white matter lesions in the elderly. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75: 1304–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Brun A, Englund E. A white matter disorder in dementia of the Alzheimer type: a pathoanatomical study. Ann Neurol 1986; 19: 253–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Englund E. Neuropathology of white matter changes in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 1998; 9(Suppl. 1): 6–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haglund M, Englund E. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy, white matter lesions and Alzheimer encephalopathy ‐ a histopathological assessment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2002; 14: 161–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Fernando MS, Simpson JE, Matthews F, Brayne C, Lewis CE, Barber R, et al White matter lesions in an unselected cohort of the elderly: molecular pathology suggests origin from chronic hypoperfusion injury. Stroke 2006; 37: 1391–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brunnstrom H, Englund E. Clinicopathological concordance in dementia diagnostics. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009; 17: 664–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Foster V, Oakley AE, Slade JY, Hall R, Polvikoski TM, Burke M, et al Pyramidal neurons of the prefrontal cortex in post‐stroke, vascular and other ageing‐related dementias. Brain 2014; 137(Pt 9): 2509–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Skrobot OA, O'Brien J, Black S, Chen C, DeCarli C, Erkinjuntti T, et al The vascular impairment of cognition classification consensus study. Alzheimers Dement 2017; 13: 624–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hyman BT, Trojanowski JQ. Consensus recommendations for the postmortem diagnosis of Alzheimer disease from the National Institute on Aging and the Reagan Institute Working Group on diagnostic criteria for the neuropathological assessment of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1997; 56: 1095–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Carrillo MC, et al National Institute on Aging‐Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement 2012; 8: 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of A beta‐deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 2002; 58: 1791–800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braak H, Braak E. Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer‐related changes. Acta Neuropathol 1991; 82: 239–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease‐associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol 2006; 112: 389–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, Sumi SM, Crain BJ, Brownlee LM, et al The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part II. Standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology 1991; 41: 479–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McKhann GM, Albert MS, Grossman M, Miller B, Dickson D, Trojanowski JQ. Clinical and pathological diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia: report of the Work Group on Frontotemporal Dementia and Pick's Disease. Arch Neurol 2001; 58: 1803–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Lee VM, Hatanpaa KJ, et al Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 2007; 114: 5–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mackenzie IR, Neumann M, Bigio EH, Cairns NJ, Alafuzoff I, Kril J, et al Nomenclature and nosology for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: an update. Acta Neuropathol 2010; 119: 1–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Crary JF, Trojanowski JQ, Schneider JA, Abisambra JF, Abner EL, Alafuzoff I, et al Primary age‐related tauopathy (PART): a common pathology associated with human aging. Acta Neuropathol 2014; 128: 755–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gold G, Giannakopoulos P, Herrmann FR, Bouras C, Kovari E. Identification of Alzheimer and vascular lesion thresholds for mixed dementia. Brain 2007; 130(Pt 11): 2830–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bjorklund E, Lindberg E, Rundgren M, Cronberg T, Friberg H, Englund E. Ischaemic brain damage after cardiac arrest and induced hypothermia–a systematic description of selective eosinophilic neuronal death. A neuropathologic study of 23 patients. Resuscitation 2014; 85: 527–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Marti HJ, Bernaudin M, Bellail A, Schoch H, Euler M, Petit E, et al Hypoxia‐induced vascular endothelial growth factor expression precedes neovascularization after cerebral ischemia. Am J Pathol 2000; 156: 965–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, et al Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia‐inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol 1996; 16: 4604–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kovacs Z, Ikezaki K, Samoto K, Inamura T, Fukui M. VEGF and flt. Expression time kinetics in rat brain infarct. Stroke 1996; 27: 1865–72; discussion 72–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sbarbati A, Pietra C, Baldassarri AM, Guerrini U, Ziviani L, Reggiani A, et al The microvascular system in ischemic cortical lesions. Acta Neuropathol 1996; 92: 56–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kalaria RN, Cohen DL, Premkumar DR, Nag S, LaManna JC, Lust WD. Vascular endothelial growth factor in Alzheimer's disease and experimental cerebral ischemia. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 1998; 62: 101–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lennmyr F, Ata KA, Funa K, Olsson Y, Terent A. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and its receptors (Flt‐1 and Flk‐1) following permanent and transient occlusion of the middle cerebral artery in the rat. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1998; 57: 874–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Plate KH, Beck H, Danner S, Allegrini PR, Wiessner C. Cell type specific upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor in an MCA‐occlusion model of cerebral infarct. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 1999; 58: 654–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang ZG, Zhang L, Tsang W, Soltanian‐Zadeh H, Morris D, Zhang R, et al Correlation of VEGF and angiopoietin expression with disruption of blood‐brain barrier and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2002; 22: 379–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu HM. Neovasculature and blood‐brain barrier in ischemic brain infarct. Acta Neuropathol 1988; 75: 422–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Krupinski J, Kaluza J, Kumar P, Kumar S, Wang JM. Role of angiogenesis in patients with cerebral ischemic stroke. Stroke 1994; 25: 1794–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Issa R, Krupinski J, Bujny T, Kumar S, Kaluza J, Kumar P. Vascular endothelial growth factor and its receptor, KDR, in human brain tissue after ischemic stroke. Lab Invest 1999; 79: 417–25 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Hayashi T, Abe K, Suzuki H, Itoyama Y. Rapid induction of vascular endothelial growth factor gene expression after transient middle cerebral artery occlusion in rats. Stroke 1997; 28: 2039–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cobbs CS, Chen J, Greenberg DA, Graham SH. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in transient focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Neurosci Lett 1998; 249: 79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lee MY, Ju WK, Cha JH, Son BC, Chun MH, Kang JK, et al Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA following transient forebrain ischemia in rats. Neurosci Lett 1999; 265: 107–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Hai J, Li ST, Lin Q, Pan QG, Gao F, Ding MX. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression and angiogenesis induced by chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in rat brain. Neurosurgery 2003; 53: 963–70; discussion 70–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ohtaki H, Fujimoto T, Sato T, Kishimoto K, Fujimoto M, Moriya M, et al Progressive expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and angiogenesis after chronic ischemic hypoperfusion in rat. Acta Neurochir Suppl 2006; 96: 283–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jing Z, Shi C, Zhu L, Xiang Y, Chen P, Xiong Z, et al Chronic cerebral hypoperfusion induces vascular plasticity and hemodynamics but also neuronal degeneration and cognitive impairment. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2015; 35: 1249–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Shu S, Zhang L, Zhu YC, Li F, Cui LY, Wang H, et al Imaging angiogenesis using (68)Ga‐NOTA‐PRGD2 positron emission tomography/computed tomography in patients with severe intracranial atherosclerotic disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2017; 37: 3401–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Thal DR, von Arnim CA, Griffin WS, Mrak RE, Walker L, Attems J, et al Frontotemporal lobar degeneration FTLD‐tau: preclinical lesions, vascular, and Alzheimer‐related co‐pathologies. J Neural Transm 2015; 122: 1007–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Raiha I, Tarvonen S, Kurki T, Rajala T, Sourander L. Relationship between vascular factors and white matter low attenuation of the brain. Acta Neurol Scand 1993; 87: 286–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Tarvonen‐Schroder S, Roytta M, Raiha I, Kurki T, Rajala T, Sourander L. Clinical features of leuko‐araiosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1996; 60: 431–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wolters FJ, Mattace‐Raso FU, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Ikram MA. Orthostatic hypotension and the long‐term risk of dementia: a population‐based study. PLoS Med 2016; 13: e1002143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pettersen JA, Keith J, Gao F, Spence JD, Black SE. CADASIL accelerated by acute hypotension: arterial and venous contribution to leukoaraiosis. Neurology 2017; 88: 1077–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Peres R, De Guio F, Chabriat H, Jouvent E. Alterations of the cerebral cortex in sporadic small vessel disease: a systematic review of in vivo MRI data. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 681–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kawai M, Kalaria RN, Harik SI, Perry G. The relationship of amyloid plaques to cerebral capillaries in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Pathol 1990; 137: 1435–46 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tarkowski E, Issa R, Sjogren M, Wallin A, Blennow K, Tarkowski A, et al Increased intrathecal levels of the angiogenic factors VEGF and TGF‐beta in Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Neurobiol Aging 2002; 23: 237–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yang SP, Bae DG, Kang HJ, Gwag BJ, Gho YS, Chae CB. Co‐accumulation of vascular endothelial growth factor with beta‐amyloid in the brain of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging 2004; 25: 283–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Meyer EP, Ulmann‐Schuler A, Staufenbiel M, Krucker T. Altered morphology and 3D architecture of brain vasculature in a mouse model for Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2008; 105: 3587–92 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Desai BS, Schneider JA, Li JL, Carvey PM, Hendey B. Evidence of angiogenic vessels in Alzheimer's disease. J Neural Transm 2009; 116: 587–97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Love S, Miners JS. Cerebrovascular disease in ageing and Alzheimer's disease. Acta Neuropathol 2016; 131: 645–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Love S, Miners JS. Cerebral hypoperfusion and the energy deficit in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Pathol 2016; 26: 607–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Desai Bradaric B, Patel A, Schneider JA, Carvey PM, Hendey B. Evidence for angiogenesis in Parkinson's disease, incidental Lewy body disease, and progressive supranuclear palsy. J Neural Transm 2012; 119: 59–71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Naldini A, Carraro F. Role of inflammatory mediators in angiogenesis. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 2005; 4: 3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Girolamo F, Coppola C, Ribatti D, Trojano M. Angiogenesis in multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Acta Neuropathol Commun 2014; 2: 84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Aguzzi A, Barres BA, Bennett ML. Microglia: scapegoat, saboteur, or something else? Science 2013; 339: 156–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Heneka MT, Kummer MP, Latz E. Innate immune activation in neurodegenerative disease. Nat Rev Immunol 2014; 14: 463–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Griffin WS, Stanley LC, Ling C, White L, MacLeod V, Perrot LJ, et al Brain interleukin 1 and S‐100 immunoreactivity are elevated in Down syndrome and Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1989; 86: 7611–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fillit H, Ding WH, Buee L, Kalman J, Altstiel L, Lawlor B, et al Elevated circulating tumor necrosis factor levels in Alzheimer's disease. Neurosci Lett 1991; 129: 318–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sjogren M, Folkesson S, Blennow K, Tarkowski E. Increased intrathecal inflammatory activity in frontotemporal dementia: pathophysiological implications. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2004; 75: 1107–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Paris D, Townsend K, Quadros A, Humphrey J, Sun J, Brem S, et al Inhibition of angiogenesis by Abeta peptides. Angiogenesis 2004; 7: 75–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Boscolo E, Folin M, Nico B, Grandi C, Mangieri D, Longo V, et al Beta amyloid angiogenic activity in vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Med 2007; 19: 581–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Cantara S, Donnini S, Morbidelli L, Giachetti A, Schulz R, Memo M, et al Physiological levels of amyloid peptides stimulate the angiogenic response through FGF‐2. FASEB J 2004; 18: 1943–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Cantara S, Ziche M, Donnini S. Opposite effects of beta amyloid on endothelial cell survival: role of fibroblast growth factor‐2 (FGF‐2). Pharmacol Rep 2005; 57(Suppl.): 138–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Patel NS, Mathura VS, Bachmeier C, Beaulieu‐Abdelahad D, Laporte V, Weeks O, et al Alzheimer's beta‐amyloid peptide blocks vascular endothelial growth factor mediated signaling via direct interaction with VEGFR‐2. J Neurochem 2010; 112: 66–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Craggs LJ, Yamamoto Y, Ihara M, Fenwick R, Burke M, Oakley AE, et al White matter pathology and disconnection in the frontal lobe in cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy (CADASIL). Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2014; 40: 591–602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Duering M, Righart R, Csanadi E, Jouvent E, Herve D, Chabriat H, et al Incident subcortical infarcts induce focal thinning in connected cortical regions. Neurology 2012; 79: 2025–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Tarkowski E, Liljeroth AM, Minthon L, Tarkowski A, Wallin A, Blennow K. Cerebral pattern of pro‐ and anti‐inflammatory cytokines in dementias. Brain Res Bull 2003; 61: 255–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Inter‐rater variability. Bland Altman diagram demonstrating the inter‐rater variability of raspberries/cm cortex in the frontal cortex. The x‐axis demonstrates the mean values of the investigators. The y‐axis represents the differences between the investigators. AD, Alzheimer's disease; FTLD, frontotemporal lobar degeneration; VaD, vascular dementia.