Abstract

Objectives

To investigate prospectively the clinical utility and influence on decision‐making of Bladder EpiCheck™, a non‐invasive urine test, in the surveillance of non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC).

Materials and Methods

Urine samples from 440 patients undergoing surveillance for NMIBC were prospectively collected at five centres and evaluated using the Bladder EpiCheck test (NCT02647112). A multivariable nomogram and decision‐curve analysis (DCA) were used to evaluate the impact of Bladder EpiCheck on decision‐making when used in routine clinical practice. The test was designed to exclude recurrent disease.

Results

Data from 357 patients were available for analysis. The test had a specificity of 88% (95% confidence interval [CI] 84–91), a negative predictive value (NPV) of 94.4% (95% CI 91–97) for the detection of any cancer and an NPV of 99.3% for the detection of high‐grade cancer. In multivariable analysis, positive Bladder EpiCheck results were independently associated with any and high‐grade disease recurrence (odds ratio [OR] 18.1, 95% CI 8.7–40.2; P < 0.001 and OR 78.3, 95% CI 19.2–547; P < 0.001). The addition of Bladder EpiCheck to standard variables improved its predictive ability for any and high‐grade disease recurrence by a difference of 16% and 22%, respectively (area under the curve 85.9% and 96.1% for any and high‐grade cancer, respectively). DCA showed an improvement in the net benefit relative to cystoscopy over a large threshold of probability, resulting in a significant reduction in unnecessary investigations. These results were similar in subgroups assessing the impact of specific clinical features.

Conclusions

Bladder EpiCheck is a robust high‐performing diagnostic test in patients with NMIBC undergoing surveillance that can potentially reduce the number of unnecessary investigations.

Keywords: non‐muscle‐invasive, urinary biomarker, prediction, surveillance, #BladderCancer, #blcsm

Introduction

Non‐muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) is a disease with recurrence rates up to 60% within the first year of diagnosis 1. Most patients will experience numerous recurrences in their life while some experience disease progression, making NMIBC a dangerous chronic disease with many events, leading to substantial burden on patients and healthcare systems. Surveillance of NMIBC to allow early identification of recurrence and progression has a high socio‐economic impact, making NMIBC one of the costliest cancers per patient 2. Moreover, the invasiveness of cystoscopy is associated with morbidity and reduced compliance over time 3, 4. Urinary cytology has a high specificity for high‐grade tumours but is limited by low sensitivity and variable performance across centres, in addition to a poor accuracy for low‐grade tumours 3, 4. Efforts have therefore focused on the development of non‐invasive urine‐based molecular tests. While some are approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and European Medicines Agency, none are widely used 5, 6, 7, 8. Indeed, most of these tests focus on single markers and do not consider the high mutation load and heterogeneity of bladder cancer (BCa), resulting in limited improvement in diagnostic performance, if any at all, compared with urine cytology and cystoscopy, and generating additional cost without improvement of clinical care 9, 10, 11, 12, 13.

Bladder EpiChecktm is a new promising urine‐based test which includes a panel of 15 DNA methylation patterns for the identification of recurrent BCa. A recent multicentre biomarker phase III trial showed that Bladder EpiCheck has a sensitivity of 91.7% in non‐Ta low‐grade recurrences and specificity of 88% for detecting BCa recurrence in patients undergoing surveillance for NMIBC 14.

In the present paper, we report a secondary, independent analysis, focusing on the clinical utility and influence on decision‐making of this test. Most studies have focused on diagnostic performance; however, for a test to add independent clinical value to the current diagnostic standards (i.e. cystoscopy and cytology), it needs to increase the discrimination of current tools integrating established predictive characteristics that are used by clinicians by a clinically and prognostically significant margin 15. In addition, its performance needs to be tested for robustness according to clinical features to make its applicability more generalizable 10. Finally, short of assessment in a biomarker‐driven randomized clinical trial, its true clinical benefit compared with the current strategy needs to be tested in clinical decision analysis 5. We hypothesized that Bladder EpiCheck would fulfil the three criteria needed in order to recommend the integration of a biomarker into daily clinical practice 16.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a secondary analysis of a multicentre prospective single‐visit trial, assessing the prognostic performance of Bladder EpiCheck as a non‐invasive urine monitoring test in patients with a history of NMIBC 14. All patients had a diagnosis of NMIBC <12 months before entering the study; they underwent standard follow‐up investigations including cystoscopy and cytology according to guideline recommendations 1 to exclude recurrent disease.

Voided urine was collected prior to cystoscopy during the follow‐up to test the Bladder EpiCheck panel and cytology.

Patients and Endpoints

In the present secondary external independent analysis, we investigated the performance of Bladder EpiCheck in the detection of BCa, defined as positive cytology and/or pathologically confirmed tumour on bladder biopsy. Moreover, we sought to investigate the clinical utility of the test and its differential impact on clinical decision‐making using multivariate analysis, changes in the area under the curve (AUC) for prediction of recurrence, robustness in subgroup analyses, and decision analytical methodology using decision‐curve analysis (DCA) 17.

Patients without Bladder EpiCheck results (n = 37), as well as those with inconclusive cytology and/or cystoscopy findings (n = 45), were excluded, leaving 357 patients for analysis (Fig. S1). All data were provided to the authors and the analyses and results were obtained without any restrictions by industry.

Biomarker Analysis

Bladder EpiCheck is a urine assay based on 15 proprietary methylation biomarkers. Methylation analyses were performed as previously described 14. Briefly, ≥10 mL of urine is centrifuged. DNA is extracted from the obtained cell pallet, digested using a methylation‐sensitive restriction enzyme which leaves methylated sequences intact, and amplified by real‐time PCR. Results are analysed with the Bladder EpiCheck software.

A positive Bladder EpiCheck result was set at an EpiScore™ threshold of ≥60.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in sequential steps 15. First, sensitivity analysis was conducted to investigate the performance of Bladder EpiCheck in the detection of any and high‐grade BCa. Second, the discrimination of Bladder EpiCheck was plotted graphically using the receiver‐operating curve and assessed using the AUC. The 95% ‘bias‐corrected and accelerated’ confidence interval (95% CI) and bias were computed via bootstrapping with 1000 replicates Third, the association of Bladder EpiCheck with the presence of BCa recurrence was tested in multivariate analysis and adjusted for the effect of standard established clinical characteristics. The generated coefficients were then used to create two nomograms, one for the prediction of the presence of any BCa and one for the prediction of high‐grade BCa. Internal validation was performed using 1000 bootstrap resamples. Calibration plots were generated to assess the performance of the models. The additive performance of Bladder EpiCheck was assessed by comparing the discrimination of models with and without Bladder EpiCheck. Fourth, the differential change in AUC attributed to Bladder EpiCheck was assessed in different clinical subgroups to determine its robustness/generalizability. Fifth, the clinical utility and the impact on decision‐making of Bladder EpiCheck was evaluated using DCA. A post hoc power analysis was performed to estimate the power of the model fitted. Finally, exploratory analysis was conducted to investigate the effect of epidemiological features on the performance of Bladder EpiCheck. P values < 0.05 were taken to indicate statistical significance. All tests were two‐sided. Statistical analyses were performed using R 3.4.2 (R project, Vienna, Austria).

Results

A total of 357 patients were included in the analyses (Fig. S1). The clinicopathological features of the included patients are shown in Table 1. At the time of evaluation, 49 patients (13.7%) had experienced intravesical disease recurrence. Overall, 70 (19.6%) had a positive Bladder EpiCheck result. The test had a sensitivity of 67.3% (95% CI 52–80) and a specificity of 88% (95% CI 84–91) for the detection of any cancer (accuracy 85.2%, 95% CI 81–89; Table 2), and a sensitivity of 88.9% (95% CI 65–99) and a specificity of 88% (95% CI 84–91) for the detection of high‐grade cancer (accuracy 88.1%, 95% CI 84–91 [Table 2]).

Table 1.

Clinicopathological features of 357 patients tested with Bladder EpiCheck during the follow‐up of non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

| Overall | |

|---|---|

| n | 357 |

| Age, median (IQR) | 70.6 (63.5–78.4) |

| Women, n (%) | 82 (23.0) |

| Occupational exposure, n (%) | |

| No | 192 (53.8) |

| Yes | 41 (11.5) |

| Unknown | 124 (34.7) |

| Smoking status, n (%) | |

| Current | 85 (23.8) |

| Former | 203 (56.9) |

| Never | 69 (19.3) |

| Years of smoking, median (IQR) | 37 (25–48) |

| Pack‐years, median (IQR) | 33 (17–53) |

| Last pathological stage (%) | |

| Ta | 219 (61.3) |

| Tis | 36 (10.1) |

| T1 | 97 (27.2) |

| NA | 5 (1.4) |

| Last pathological grade (%) | |

| Low grade | 182 (51) |

| High grade | 170 (47.6) |

| NA | 5 (1.4) |

| Bladder EpiScore, median (IQR) | 20 (13–32) |

| Positive Bladder EpiCheck, n (%) | 70 (19.6) |

| Cytology, n (%) | |

| Negative | 324 (90.8) |

| Positive | 22 (6.2) |

| Equivocal | 11 (3.1) |

| Cystoscopy, n (%) | |

| Negative | 305 (85.4) |

| Positive | 52 (14.6) |

| Pathology performed, n (%) | 59 (16.5) |

| Pathology stage, n (%) | |

| Ta | 27 (7.6) |

| Cis | 3 (0.8) |

| T0 | 21 (5.9) |

| T1 | 7 (2.0) |

| T2 | 1 (0.3) |

| Pathology grade, n (%) | |

| High grade | 18 (5.0) |

| Low grade | 20 (5.6) |

| Adjuvant intravesical therapy, n (%) | |

| BCG | 72 (20.2) |

| MMC | 111 (31.1) |

| Both | 59 (16.5) |

| None | 101 (28.3) |

| Other chemotherapy | 14 (3.9) |

| Ongoing intravesical treatment at the time of testing (%) | 102 (28.6) |

IQR, interquartile range; MMC, mitomycin‐C.

Table 2.

Sensitivity analyses for the performance of Bladder EpiCheck in the detection of cancer in the follow‐up of 357 patients with previous non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

| Any BCa | High‐grade BCa | Low‐grade BCa | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, % (95% CI) | 67 (52–80) | 89 (65–99) | 40 (19–64) | |||

| Specificity, % (95% CI) | 88 (84–91) | 88 (84–91) | 88 (84–91) | |||

| PPV, % (95% CI) | 47 (35–59) | 30 (18–44) | 18 (8–32) | |||

| NPV, % (95% CI) | 94 (91–97) | 99 (97–100) | 96 (93–98) | |||

| Accuracy, % (95% CI) | 85 (81–89) | 88 (84–91) | 85 (81–89) | |||

| Any BCa absent | Any BCa present | High‐grade BCa absent | High‐grade BCa present | Low‐grade BCa absent | Low‐grade BCa present | |

| Negative EpiCheck, n (%) | 271 (75.9) | 16 (4.5) | 285 (79.8) | 2 (0.6) | 275 (77) | 12 (3.4) |

| Positive EpiCheck, n (%) | 37 (10.4) | 33 (9.2) | 54 (15.1) | 16 (4.5) | 62 (17.4) | 8 (2.2) |

BCa, bladder cancer; NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value.

In logistic regression analyses, a positive Bladder EpiCheck result predicted the presence of any cancer with an odds ratio (OR) of 15.1 (95% CI 7.71–30.77; P < 0.001) and the presence of high‐grade cancer with an OR of 58.6 (95% CI 15.8–380; P < 0.001 [Table 3]). As a continuous variable, an increase in one Bladder EpiScore point corresponds to a 4% increase in the risk of harbouring any BCa and an 8% increase in the risk of harbouring a high‐grade BCa (Table 3). On multivariable logistic regression analysis that adjusted for the effects of pathological stage, grade, age, gender, time from last recurrence and ongoing intravesical therapy (base model) Bladder EpiCheck remained independently associated with the presence of any (OR 18.1, 95% CI 8.66–40.2; P < 0.001) and high‐grade BCa (OR 78.3, 95% CI 19.2–547; P < 0.001 [Tables 4 and 5]). Compared with the base model, the addition of Bladder EpiCheck significantly improved the prediction for any recurrence by 16% and high‐grade recurrence by 22% (AUC 85.9% and 96.1% for any and high‐grade cancer, respectively [Tables 4 and 5, Fig. S2]).

Table 3.

Univariable logistic regression analyses for the prediction of cancer based on the Bladder EpiCheck in the follow‐up of 357 patients with previous non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

| Prediction of any BCa | Prediction of high‐grade BCa | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| a) Positive Bladder EpiCheck result | 15.1 | 7.71–30.77 | <0.001 | 58.6 | 15.8–380 | <0.001 |

| b) Bladder EpiScore (continuous) | 1.04 | 1.03–1.06 | <0.001 | 1.08 | 1.05–1.12 | <0.001 |

BCa, bladder cancer; OR, odds ratio.

Table 4.

Multivariable regression analyses for the prediction of any cancer in the follow‐up of 352 patients with previous non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

| Multivariable logistic regression analysis for positive Bladder EpiCheck | Multivariable logistic regression analysis for continuous Bladder EpiScore | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Last pathological stage (Ta reference category) | |||||||

| Tis | 1.75 | 0.40–7.61 | 0.45 | 1.63 | 0.36–7.34 | 0.52 | |

| T1 | 1.36 | 0.43–4.36 | 0.60 | 1.47 | 0.46–4.76 | 0.52 | |

| High grade | 0.74 | 0.25–2.09 | 0.58 | 0.68 | 0.23–1.91 | 0.47 | |

| Age (continuous) | 0.99 | 0.96–1.03 | 0.84 | 0.99 | 0.95–1.02 | 0.56 | |

| Female gender | 1.22 | 0.51–2.78 | 0.64 | 1.26 | 0.53–2.90 | 0.58 | |

| Time from last recurrence to urine collection | 0.91 | 0.83–0.99 | 0.05 | 0.92 | 0.83–1.002 | 0.07 | |

| Ongoing intravesical therapy (never reference category) | |||||||

| No | 1.24 | 0.56–2.86 | 0.60 | 1.20 | 0.53–2.79 | 0.65 | |

| Yes | 0.27 | 0.08–0.84 | 0.03 | 0.29 | 0.08–0.91 | 0.04 | |

| AUC 66.9% (95% CI 58.1–70.7) | |||||||

| Positive EpiCheck | 18.1 | 8.66–40.2 | <0.001 | EpiScore (continuous) | 1.05 | 1.04–1.06 | <0.001 |

| AUC 85.1% (95% CI 78.2–88.9) | AUC 85.9% (95% CI 79.2–89.5) | ||||||

AUC, area under the curve; OR, odds ratio.

Table 5.

Multivariable regression analyses for the prediction of high‐grade cancer in the follow‐up of 321 patients with previous non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

| Multivariable logistic regression analysis for positive Bladder EpiCheck | Multivariable logistic regression analysis for continuous Bladder EpiScore | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | ||

| Last pathological stage (Ta reference category) | |||||||

| Tis | 3.96 | 0.42–40.7 | 0.23 | 5.44 | 0.49–69.0 | 0.99 | |

| T1 | 3.43 | 0.63–23.1 | 0.17 | 5.62 | 0.88–46.9 | 0.17 | |

| High grade | 1.00 | 0.18–4.97 | 0.99 | 0.64 | 0.09–3.54 | 0.08 | |

| Age (continuous) | 0.98 | 0.93–1.05 | 0.63 | 0.97 | 0.91–1.04 | 0.62 | |

| Female gender | 0.77 | 0.14–3.26 | 0.73 | 0.93 | 0.16–4.36 | 0.39 | |

| Time from last recurrence to urine collection | 0.82 | 0.66–0.96 | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.65–0.99 | 0.93 | |

| Ongoing intravesical therapy (never reference category) | |||||||

| No | 0.95 | 0.22–4.09 | 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.06–2.33 | 0.81 | |

| Yes | 0.40 | 0.06–2.07 | 0.29 | 0.40 | 0.06–2.33 | 0.32 | |

| AUC 72.7% (95% CI 62.7–76.6) | |||||||

| Positive EpiCheck | 78.3 | 19.2–547 | <0.001 | EpiScore (continuous) | 1.08 | 1.05–1.12 | <0.001 |

| AUC 94.9% (95% CI 88.3–96.8) | AUC 96.1% (95% CI 90.9–97.9) | ||||||

AUC, area under the curve; OR, odds ratio.

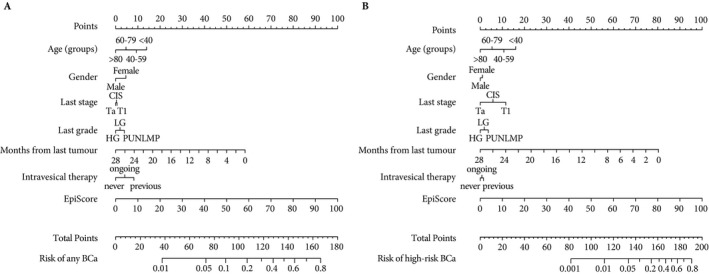

The clinical weight of Bladder EpiCheck in identifying any and high‐grade recurrence is depicted in nomograms that were built using the coefficients of multivariable analyses (Fig. 1). Internal validation, using the bootstrap method with 1000 resamples, showed that the model for the detection of any BCa and that for the detection of high‐grade BCa were overfitted by 1.4% and 0.9%, respectively. Specifically, for the detection of any BCa, the AUC for the model fitted to the original data was 85.9% (95% CI 79.2–89.5). For the detection of high‐grade BCa, the AUC for the model fitted to the original data was 96.1% (95% CI 90.9–97.9).

Figure 1.

Logistic regression nomogram for the prediction of bladder cancer (BCa) (A) and high‐risk BCa (B) in the follow‐up of patients with previous non‐muscle invasive bladder cancer. CIS, carcinoma in situ; LG, low grade; HG, high grade; PUNLMP, papillary urothelial neoplasm of low malignant potential.

Calibration plots showed a good performance across predicting probabilities (Fig. S3). Exploratory analyses showed that the performance of the test, evaluated by the AUC, is not affected by clinical features such as gender, age, smoking status or occupational exposure ( Figs S4 and S5).

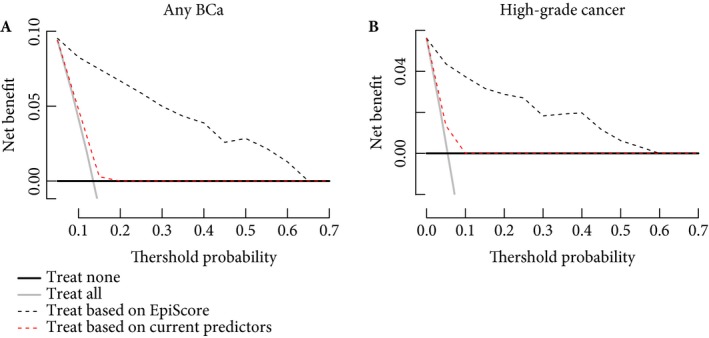

The DCA showed that current predictors (i.e. last stage, last grade) perform no better than cystoscopy in every patient (all patients need cystoscopy), while the use of Bladder EpiCheck for the purpose of deciding whether to perform a cystoscopy or not during the follow‐up of patients with a history of NMIBC provided a net benefit relative to the current strategy of evaluating all patients with cystoscopy, or that of testing none of the patients (Fig. 2). This was true across threshold probabilities between 10–60% for the presence of any BCa and 5–55% for the presence of high‐grade BCa, a range within which all decisions based on standard predictors is based in clinical practice. This translates into saving of unnecessary cystoscopy and cytology in patients with a risk of recurrence >10% for any BCa and >5% for high‐grade BCa.

Figure 2.

Decision‐curve analysis assessing the clinical impact of the nomograms estimating the prediction of bladder cancer (BCa) (A) and high‐risk BCa (B) in the follow‐up of patients with previous non‐muscle‐invasive BCa. The inclusion of EpiScore is compared with current clinical prognostic models and the strategies of evaluating all or none of the patients with cystoscopy and cytology.

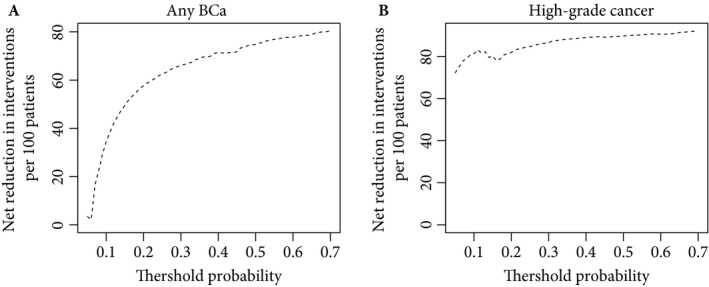

Decision‐making based on Bladder EpiCheck could significantly reduce the number of unnecessary cystoscopies without missing any cancer as depicted in Tables 6 and 7 and Fig. 3.

Table 6.

Net benefits and interventions avoided for the models assessed through decision‐curve analysis for the detection of any cancer in the follow‐up of 352 patients with non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

| Threshold probability (%) | Net benefits | Interventions avoided per 100 patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treat all | Treat none | Treat based on Bladder EpiScore | Treat based on current predictors | Advantage | Bladder EpiScore | Current predictors | |

| 5 | 0.09 | 0 | 0.09 | 0.089 | 0.001 | 2.6 | 0 |

| 10 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 35.2 | 3.98 |

| 15 | −0.01 | 0 | 0.07 | 0.003 | 0.067 | 49.5 | 8.8 |

| 20 | −0.08 | 0 | 0.07 | 0 | 0.14 | 57.1 | 30.4 |

| 25 | −0.01 | 0 | 0.06 | 0 | 0.21 | 61.9 | 44.3 |

| 30 | −0.02 | 0 | 0.05 | 0 | 0.28 | 65.2 | 53.6 |

| 35 | −0.03 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.37 | 68.3 | 60.2 |

| 40 | −0.04 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.47 | 71 | 65.2 |

| 45 | −0.06 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.59 | 72 | 69.1 |

| 50 | −0.07 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.75 | 75 | 72.1 |

| 55 | −0.09 | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.93 | 76.5 | 74.7 |

| 60 | −1.1 | 0 | 0.01 | 0 | 1.16 | 77.6 | 76.8 |

| 65 | −1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.46 | 78.6 | 78.6 |

| 70 | −1.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.87 | 80 | 80 |

In decision‐curve analysis prediction models are compared to two default strategies: (i) assume that all patients are test positive and therefore treat everyone, or (ii) assume that all patients are test negative and offer treatment to no one. The table shows the net benefits for a strategy of performing a cystoscopy in every patient (treat all), in no one (treat none), based on Bladder EpiCheck and on current predictors (i.e. last stage and last grade). For example, given a personal threshold probability of 15% (i.e. one would undergo a cystoscopy if the probability of cancer is >15%) the value of 0.07 can be interpreted as: ‘Compared to performing no cystoscopy, performing a cystoscopy on the basis of the Bladder EpiCheck is the equivalent of a strategy that found seven cancers per 100 patients without conducting any unnecessary cystoscopy’. Moreover, at this threshold probability every decision based on Bladder EpiCheck would avoid 49.5% of unnecessary cystoscopies without missing any cancer.

Table 7.

Net benefits and interventions avoided for the models assessed through decision‐curve analysis for the detection of high‐grade cancer in the follow‐up of 321 patients with non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

| Threshold probability (%) | Net benefit | Interventions avoided per 100 patients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treat all | Treat none | Bladder EpiScore | Current predictors | Advantage | Bladder EpiScore | Current predictors | |

| 5 | 0.006 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.013 | 0.04 | 70.7 | 13.4 |

| 10 | −0.05 | 0 | 0.04 | 0 | 0.09 | 77.6 | 44 |

| 15 | −0.11 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.14 | 80.6 | 63 |

| 20 | −0.18 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.21 | 83.5 | 72 |

| 25 | −0.26 | 0 | 0.03 | 0 | 0.28 | 85.7 | 77.6 |

| 30 | −0.35 | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.37 | 85.6 | 81.3 |

| 35 | −0.45 | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.47 | 87.5 | 84 |

| 40 | −0.57 | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 0.59 | 88.9 | 86 |

| 45 | −0.72 | 0 | 0.012 | 0 | 0.73 | 89 | 87.5 |

| 50 | −0.89 | 0 | 0.006 | 0 | 0.89 | 89.4 | 88.8 |

| 55 | −1.1 | 0 | 0.003 | 0 | 1.1 | 90 | 89.8 |

| 60 | −1.36 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.36 | 90.6 | 91 |

| 65 | −1.7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.7 | 91.4 | 92 |

| 70 | −2.15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.15 | 92 | 92 |

In decision‐curve analysis prediction models are compared to two default strategies: (i) assume that all patients are test positive and therefore treat everyone, or (ii) assume that all patients are test negative and offer treatment to no one. The table shows the net benefits for a strategy of performing a cystoscopy in every patient (treat all), in no one (treat none), based on Bladder EpiCheck and on current predictors (i.e. last stage and last grade). For example, given a personal threshold probability of 5% (i.e. a patient would undergo a cystoscopy if the probability of high‐grade cancer is >5%) the value of 0.04 can be interpreted as: ‘Compared to performing no cystoscopy, performing a cystoscopy on the basis of the Bladder EpiCheck is the equivalent of a strategy that found four cancers per 100 patients without conducting any unnecessary cystoscopy.’ Moreover, at this threshold probability every decision based on Bladder EpiCheck would avoid 70.7% of unnecessary cystoscopies without missing any cancer.

Figure 3.

Interventions avoided by the use of Bladder EpiCheck in the decision‐making of evaluating a patient with cystoscopy and cytology during the follow‐up of non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer (BCa), based on the risk of having any BCa (A) or high‐risk BCa (B) recurrence.

The post hoc power calculation showed that we had adequate power to detect cancer recurrence. Specifically, with a sample size of 352 patients and a multivariable logistic regression model with seven degrees of freedom, we calculated a power very close to 100%, with a 5% significance level to detect an OR of 1.05 for Bladder EpiScore.

Discussion

In this secondary independent analysis of the Bladder EpiCheck study 14, we confirmed the high diagnostic accuracy and performance of the Bladder EpiCheck test. NMIBC is one of the most expensive cancers per patient, largely because of its high rate of recurrences, necessitating intense surveillance 2. Lowering the number of cystoscopies would reduce the cost of surveillance and simultaneously improve patients’ quality of life. In this clinical setting, we need a test with high negative predictive value (NPV) for all BCa but specifically for high‐grade BCa, which is the most important not to miss as it could lead to stage progression. Indeed, NPV is to be considered a point of reference from which measurements may be made in order to avoid unnecessary intervention, thereby improving patients’ quality of life. By contrast, positive predictive value has more value in a screening setting where early detection is essential; however, the influence of disease prevalence on predictive values must be taken into account in the BCa population for biomarker discovery, design and validation 15.

In accordance with the first report of the trial, we found that Bladder EpiCheck could exclude the presence of high‐grade BCa with an NPV of 99.3%, that is a false‐negative result of 0.7 per 100 patients with negative results. This provides physicians and patients with a very high certainty that no tumour recurrence is present if the test is negative, largely outperforming the currently available urinary‐based biomarkers and cystoscopy. For example, in recent studies evaluating blue‐light cystoscopy in the surveillance setting, the sensitivity and specificity of white‐light cystoscopy were 79.3% and 78%, respectively 18. Moreover, the overall sensitivity and specificity for urine‐based biomarkers, such as NMP22, reached only 73% and 80%, respectively 19. Similar results can be observed for other commercially available tests, such as ImmunoCyt™ and UroVysion™ 20. Owing to poor study design, resulting in a wide range of performances and a sensitivity that is usually relatively high at the cost of lower specificity, none of these urinary tests is recommended in the surveillance of NMIBC by current guidelines 1. Bladder EpiCheck achieved a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 88% for high‐grade BCa.

Urine cytology, the only established urine‐based ‘marker’ used in routine clinical practice for the diagnosis and surveillance of BCa is limited by suboptimal NPV, specifically for low‐grade cancer, and does not comply fully with the requirements set forth for an ideal biomarker 16. As the association of Bladder EpiCheck with positive urine cytology was an endpoint in the present analysis, a direct comparison of the performance of these two tests was not possible. We chose positive cytology as an endpoint because white‐light cystoscopy has a significant false‐negative rate and cytology a high true‐positive rate 1. Nevertheless, considering only the accuracy for low‐grade BCa, Bladder EpiCheck largely outperformed cytology, which in the present cohort was 20% in agreement with the reported literature 1, 4. While the diagnostic performance of a test is important, its association with the outcome of interest should be independent of established clinicopathological features 15 and it should further add prognostically and clinically independent information to what we already know.

We found that Bladder EpiCheck was independently associated with the presence of BCa in multivariable analysis and its diagnostic AUC performance was robust within subgroups. Specifically, the results of Bladder EpiCheck were independent of previous or ongoing intravesical therapy. This represents a great advantage compared with other available urine biomarkers, whose performance varies with different clinical features 21 or which have high variability in performance depending on the selected threshold 22. Indeed, Bladder EpiCheck reached an AUC of 83% for the prediction of any cancer and 95% for the prediction of high‐grade cancer in multivariable analysis, significantly improving the AUC of a prediction model which included pathological stage, grade, age, gender, time from last recurrence and ongoing intravesical therapy by 16% and 22%, respectively. However, achieving independent association on multivariable testing and improvement in AUC does not directly translate into clinical utility, making decision analyses critical.

On DCA, we found that Bladder EpiCheck could provide a significant clinical benefit by reducing the number of unnecessary cystoscopies without missing any cancer during the follow‐up of patients with NMIBC. Current guidelines suggest standardized follow‐up of patients with NMIBC 1, but the invasiveness of the procedure and the intervals often result in patient anxiety, organizational challenges and deviation from recommended standards 23, 24. Biomarkers in surveillance could help reduce the number of unnecessary cystoscopies, thereby reducing the economic burden, improving patient's quality of life and, ultimately, allowing individualization of follow‐up and therapy 10, 15, 16. Several studies have proposed replacing or alternating follow‐up cystoscopies with urinary biomarkers, but none of the tests to date could reach sufficient diagnostic accuracy to reliably replace cystoscopy as the reference standard 5, 8, 10, 15, 16, 25. A recent up‐to‐date catalogue summarizes the performance of panels as well as single urinary biomarkers in the surveillance of NMIBC 26. None of these tests achieved a diagnostic accuracy comparable to the Bladder EpiCheck. Moreover, the Bladder EpiCheck demonstrated a robust performance and significant impact on clinical decision‐making and, based on current data, could therefore be implemented in clinical practice to decide whether to perform a cystoscopy or not. For example, given a personal threshold probability of 15% (i.e. a patient would undergo a cystoscopy if the probability of cancer was >15%) every decision based on Bladder EpiCheck would avoid 49.5% of unnecessary cystoscopies without missing any cancer.

Limitations of the present study are those inherent to its single‐visit design, similar to most diagnostic biomarker studies. Because a negative test does not exclude future recurrences, future studies should focus on longitudinal assessment of changes in the Bladder EpiScore as these may give insight into the risk of development of urothelial cancer in patients with subclinical disease 27. Indeed, a movement toward risk‐based counselling and decision‐making holds the promise of personalizing medicine in a highly heterogeneous, complex clinical entity such as NMIBC.

In conclusion, the Bladder EpiCheck test offers a highly promising diagnostic performance in ruling out BCa recurrence and has relevant clinical consequences as it could reduce the number of unnecessary investigations, thereby reducing costs per patient, improving patients’ quality of life and providing safe follow‐up of patients with NMIBC.

Conflicts of Interest

Dr D'Andrea reports personal fees from Nucleix (Rehovot, Israel), during the conduct of the study. Drs Korn, Soria and Zehetmayer have nothing to disclose. Dr Witjes reports personal fees from Nucleix during the conduct of the study. Dr Gust reports personal fees and other fees from serving on the Advisory Boards for Cepheid, Roche, MSD and Ferring and as a Speaker for Astellas, Astra Zeneca, BMS, Ipsen, MSD and Roche, and meeting/travel expenses from Allergan, Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, BMS, Janssen, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre and Roche outside the submitted work. Dr Shariat reports personal fees from Nucleix (Rehovot, Israel), during the conduct of the study, other from Method to determine prognosis after therapy for prostate cancer (granted 9 June 2002), other from Method to determine prognosis after therapy for bladder cancer (granted 19 June 2003), other from Prognostic methods for patients with prostatic disease (granted 5 August 2004), other from Soluble Fas urinary marker for the detection of bladder transitional cell carcinoma (granted 20 July 2010), and other from Astellas, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, BMS, Cepheid, Ferring, Ipsen, Janssen, Lilly, MSD, Olympus, Pfizer, Pierre Fabre, Roche, Sanochemia, Sanofi and Wolff, outside the submitted work.

Abbreviations

- NMIBC

non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer

- DCA

decision‐curve analysis

- NPV

negative predictive value

- OR

odds ratio

- BCa

bladder cancer

- AUC

area under the curve

Supporting information

Figure S1. STARD (Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy) diagram for patient recruitment and enrollment.

Figure S2. Multivariable receiver operating curves (ROC) and respective areas under the curve (AUC) for the base model and model including EpiScore™.

Figure S3. Calibration plot of the nomograms for the prediction of bladder cancer (A) and high‐grade bladder cancer (B) in the follow‐up of patients with previous non‐muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Figure S4. Diagnostic AUC for any cancer by subgroups.

Figure S5. Diagnostic AUC for high‐grade cancer by subgroups.

Acknowledgements

This study was sponsored by Nucleix, Rehovot, Israel.

References

- 1. Babjuk M, Böhle A, Burger M et al. EAU guidelines on non‐muscle‐invasive urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: update 2016. Eur Urol 2017; 71: 447–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leal J, Luengo‐Fernandez R, Sullivan R et al. Economic burden of bladder cancer across the European Union. Eur Urol 2016; 69: 438–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kamat AM, Hegarty PK, Gee JR et al. ICUD‐EAU International Consultation on Bladder Cancer 2012: screening, diagnosis, and molecular markers. Eur Urol 2013; 63: 4–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Karakiewicz PI, Benayoun S, Zippe C et al. Institutional variability in the accuracy of urinary cytology for predicting recurrence of transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder. BJU Int 2006; 97: 997–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lotan Y, O'Sullivan P, Raman JD et al. Clinical comparison of noninvasive urine tests for ruling out recurrent urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol 2017; 35: 531.e15–e22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmitz‐Dräger BJ, Todenhöfer T, Van Rhijn B et al. Considerations on the use of urine markers in the management of patients with low‐/intermediate‐risk non‐muscle invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol 2014; 32: 1061–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kamat AM, Vlahou A, Taylor JA et al. Considerations on the use of urine markers in the management of patients with high‐grade non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer. Urol Oncol 2014; 32: 1069–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmitz‐Dräger C, Bonberg N, Pesch B et al. Replacing cystoscopy by urine markers in the follow‐up of patients with low‐risk non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer?‐An International Bladder Cancer Network project. Urol Oncol 2016; 34: 452–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kamat AM, Karam JA, Grossman HB et al. Prospective trial to identify optimal bladder cancer surveillance protocol: reducing costs while maximizing sensitivity. BJU Int 2011; 108: 1119–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lotan Y, Shariat SF, Schmitz‐Dräger BJ et al. Considerations on implementing diagnostic markers into clinical decision making in bladder cancer. Urol Oncol 2010; 28: 441–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Svatek RS, Sagalowsky AI, Lotan Y. Economic impact of screening for bladder cancer using bladder tumor markers: a decision analysis. Urol Oncol 2006; 24: 338–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kamat AM, Hahn NM, Efstathiou JA et al. Bladder cancer. Lancet 2016; 388: 2796–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Bekker‐Grob EW, van der Aa MNM, Zwarthoff EC et al. Non‐muscle‐invasive bladder cancer surveillance for which cystoscopy is partly replaced by microsatellite analysis of urine: a cost‐effective alternative? BJU Int 2009; 104: 41–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Witjes JA, Morote J, Cornel EB et al. Performance of the bladder EpiCheck™ methylation test for patients under surveillance for non–muscle‐invasive bladder cancer: results of a multicenter, prospective, blinded clinical trial. Eur Urol Oncol 2018; 1: 307–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shariat SF, Lotan Y, Vickers A et al. Statistical consideration for clinical biomarker research in bladder cancer. Urol Oncol 2010; 28: 389–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bensalah K, Montorsi F, Shariat SF. Challenges of cancer biomarker profiling. Eur Urol 2007; 52: 1601–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vickers AJ. Decision analysis for the evaluation of diagnostic tests, prediction models and molecular markers. Am Stat 2008; 62: 314–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Daneshmand S, Patel S, Lotan Y et al. Efficacy and safety of blue light flexible cystoscopy with hexaminolevulinate in the surveillance of bladder cancer: a phase III, comparative, multicenter study. J Urol 2018; 199: 1158–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lotan Y, Roehrborn CG. Sensitivity and specificity of commonly available bladder tumor markers versus cytology: results of a comprehensive literature review and meta‐analyses. Urology 2003; 61: 109–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shariat SF, Karam JA, Lotan Y et al. Critical evaluation of urinary markers for bladder cancer detection and monitoring. Rev Urol 2008; 10: 120–35 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gopalakrishna A, Longo TA, Fantony JJ et al. The diagnostic accuracy of urine‐based tests for bladder cancer varies greatly by patient. BMC Urol 2016; 16: 30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Shariat SF, Marberger MJ, Lotan Y et al. Variability in the performance of nuclear matrix protein 22 for the detection of bladder cancer. J Urol 2006; 176: 919–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chamie K, Saigal CS, Lai J et al. Quality of care in patients with bladder cancer: a case report? Cancer 2012; 118: 1412–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Koo K, Zubkoff L, Sirovich BE et al. The burden of cystoscopic bladder cancer surveillance: anxiety, discomfort, and patient preferences for decision making. Urology 2017; 108: 122–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lotan Y, Roehrborn CG. Cost‐effectiveness of a modified care protocol substituting bladder tumor markers for cystoscopy for the followup of patients with transitional cell carcinoma of the bladder: a decision analytical approach. J Urol 2002; 167: 75–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Soria F, Droller MJ, Lotan Y et al. An up‐to‐date catalog of available urinary biomarkers for the surveillance of non‐muscle invasive bladder cancer. World J Urol 2018; 36: 1981–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gopalakrishna A, Fantony JJ, Longo TA et al. Anticipatory positive urine tests for bladder cancer. Ann Surg Oncol 2017; 24: 1747–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. STARD (Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy) diagram for patient recruitment and enrollment.

Figure S2. Multivariable receiver operating curves (ROC) and respective areas under the curve (AUC) for the base model and model including EpiScore™.

Figure S3. Calibration plot of the nomograms for the prediction of bladder cancer (A) and high‐grade bladder cancer (B) in the follow‐up of patients with previous non‐muscle invasive bladder cancer.

Figure S4. Diagnostic AUC for any cancer by subgroups.

Figure S5. Diagnostic AUC for high‐grade cancer by subgroups.