Abstract

Copeptin is secreted in an equimolar amount to arginine vasopressin (AVP) but can easily be measured in plasma or serum with a sandwich immunoassay. The main stimuli for copeptin are similar to AVP, that is an increase in osmolality and a decrease in arterial blood volume and pressure. A high correlation between copeptin and AVP has been shown. Accordingly, copeptin mirrors the amount of AVP in the circulation. Copeptin has, therefore, been evaluated as diagnostic biomarker in vasopressin‐dependent disorders of body fluid homeostasis. Disorders of body fluid homeostasis are common and can be divided into hyper‐ and hypoosmolar circumstances: the classical hyperosmolar disorder is diabetes insipidus, while the most common hypoosmolar disorder is the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIAD). Copeptin measurement has led to a “revival” of the direct test in the differential diagnosis of diabetes insipidus. Baseline copeptin levels, without prior thirsting, unequivocally identify patients with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. In contrast, for the difficult differentiation between central diabetes insipidus and primary polydipsia, a stimulated copeptin level of 4.9 pmol/L upon hypertonic saline infusion differentiates these two entities with a high diagnostic accuracy and is clearly superior to the classical water deprivation test. On the contrary, in the SIAD, copeptin measurement is of only little diagnostic value. Copeptin levels widely overlap in patients with hyponatraemia and emphasize the heterogeneity of the disease. Additionally, a variety of factors lead to unspecific copeptin elevations in the acute setting further complicating its interpretation. The broad use of copeptin as diagnostic marker in hyponatraemia and specifically to detect cancer‐related disease in SIADH patients can, therefore, not be recommended.

Keywords: copeptin, diabetes insipidus, diagnosis, hypernatremia, hyponatraemia, primary polydipsia, SIAD

1. INTRODUCTION

Arginine vasopressin (AVP) is the main regulating hormone of body fluid homeostasis. It is secreted from the posterior pituitary upon osmotic or nonosmotic stimuli, with the main osmotic stimulus being increased plasma osmolality and the main nonosmotic stimulus being hypovolaemia and promotes water reabsorption via V2 receptors in the kidney, thereby normalizing hypertonicity and vasomotor tone.

Disorders of body fluid homeostasis are common and can be divided into hyper‐ and hypoosmolar circumstances: the classical hyperosmolar disorder (deficiency of body fluid relative to body solute1) is diabetes insipidus, while the most common hypoosmolar disorder (excess of body fluid relative to body solute) is the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (SIAD).

Diabetes insipidus belongs to the polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome and is characterized by a high urinary output of more than 50 ml per kg body weight per 24 hours, accompanied by polydipsia of more than 3 L a day.2 After exclusion of osmotic diuresis (such as hyperglycaemia), the differential diagnosis of polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome includes impaired AVP synthesis (central diabetes insipidus) or action (nephrogenic diabetes insipidus) as well as primary polydipsia.

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis is the predominant cause of hyponatraemia3, 4 and is characterized by reduced free water excretion and secondary natriuresis,5 mostly due to an imbalanced secretion of the antidiuretic hormone AVP.6, 7

Arginine vasopressin measurement could theoretically help in the guidance of diagnosis and treatment of body fluid disorders. However, AVP is difficult to measure and unreliable, mainly due to complex pre‐analytical requirements.8 Copeptin is the C‐terminal segment of the AVP precursor peptide and mirrors AVP concentrations.9 It can easily be measured providing a reliable surrogate marker for AVP.

This review focuses on copeptin and its role in the diagnosis and differential diagnosis of diabetes insipidus and SIAD.

2. COPEPTIN

Copeptin was detected in 1972 in the posterior pituitary of pigs.10, 11 Copeptin derives from the precursor protein pre‐provasopressin together with AVP and neurophysin II. It is a 39‐amino acid‐long glycosylated peptide with a leucine‐rich core region.11, 12 Its molecular mass is around 5 kDa (Figure 1).13

Figure 1.

Structure of Copeptin. Structure of pre‐provasopressin. The prohormone is packaged into neurosecretory granules of magnocellular neurons. During axonal transport of the granules from the hypothalamus to the posterior pituitary, enzymatic cleavage of the prohormone generates the final products: AVP, neurophysin and the COOH‐terminal glycoprotein copeptin [Colour figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com]

While AVP has been characterized as the main hormone for the regulation of the body fluid homeostasis and vascular tonus as well as an endocrine stress hormone,14, 15 the physiological function of copeptin is largely unknown. Its proposed role as a prolactin‐releasing factor could not be confirmed.16, 17 Another function could be the involvement of copeptin in the folding of the AVP precursor, as it seems to interact with the calnexin‐calreticulin system in the endoplasmic reticulum.18, 19 Accordingly, a possible relationship between certain forms of familial cranial diabetes insipidus and the inefficient folding of the AVP precursor in the absence of copeptin was proposed20; however, further examinations are needed.

The elimination pathway of copeptin has not been clarified yet; a renal clearance was suggested as studies from patients with impaired kidney function showed an inverse correlation of plasma copeptin levels with the glomerular filtration rate.21 Another study evaluating serial measurements of copeptin and AVP during osmotic stimulation, as well as after osmotic suppression in healthy volunteers, showed a two times longer decay kinetic of copeptin compared with AVP (26 minutes vs 12 minutes).22

2.1. Copeptin as reliable surrogate marker of AVP

Today, the main use of copeptin is its role as stable surrogate marker for AVP concentrations in humans.13 A prospective trial with 91 healthy volunteers undergoing a standardized test protocol with osmotic stimulation via hypertonic saline infusion and following osmotic suppression with oral and intravenous water load23 showed a strong correlation between plasma AVP (when measured with a well‐established radio‐immunoassay) and copeptin levels with a correlation index of r = 0.83.22 Notably, the correlation with plasma osmolality was stronger for copeptin than for AVP.9 (Figure 2A,B).

Figure 2.

Correlation of copeptin with AVP and plasma osmolality. A, The correlation of copeptin with AVP during osmotic stimulation with hypertonic saline infusion (modified from Rref.23). Linear regression (solid line) with slope b and coefficient of determination R 2, the smoothing line (dashed line) and Spearman's rank correlation coefficient rS are shown. B, The correlation of plasma copeptin and AVP concentrations as a scatter plot ranging from hypoosmolality (induced by water load) to hyperosmolality (induced by hypertonic saline infusion) (modified from Ref.9). rS denotes Spearman's rank correlation coefficients

2.2. Stimuli of copeptin release

The main stimuli for copeptin are similar to AVP, that is the main osmotic stimulus being an increase in osmolality and the main nonosmotic stimulus being a decrease in arterial blood volume and pressure.9, 24 The osmotic trigger of copeptin secretion was first shown in a study with 24 healthy adults, whereby fluid deprivation and hypertonic saline infusion lead to a significant increase in plasma copeptin levels (4.6 ± 1.7 to 9.2 ± 5.2 pmol/L and 4.9 ± 3.0 to 19.9 ± 4.8 pmol/L respectively, P < 0.0001).24 Conversely, hypotonic saline infusion leads to a prompt suppression of plasma copeptin levels in the same volunteers,24 as did oral water load in a similar study with 20 healthy volunteers9 (6.2 ± 2.4 to 2.4 ± 2.1 pmol/L [P < 0.01], and 3.3‐2.0 pmol/L respectively).

The prompt response of copeptin secretion upon the nonosmotic stimulus of volume depletion was shown in a baboon model of experimental haemorrhagic shock,25 where plasma copeptin concentration rapidly increased from median levels of 7.5‐269 pmol/L, with a subsequent decline to 27 pmol/L after reperfusion. The much higher increase in copeptin upon hypovolaemic shock highlights the significant difference between the magnitude of osmotic and nonosmotic AVP and copeptin secretion.

In addition to osmotic and arterial pressure, somatic stress as seen in all states of serious illness is also a major determinant of copeptin regulation. In fact, several observational studies confirmed the predictive character of plasma copeptin as an unspecific stress marker in various states of acute diseases, including ischaemic stroke, myocardial infarction and lower respiratory tract infections with copeptin levels up to 100 pmol/L in severely ill patients.26, 27, 28 This stress‐related increase in copeptin again shows the higher magnitude in increase compared to the “classical” osmotic stimulus.

Compared to somatic stress, the influence of psychological stress on copeptin release is rather limited, though existent, as shown by recent studies in medical students tested before and after a written examination (decrease from 3.1 pmol/L before the examination to 2.3 pmol/L after the examination, P < 0.001) and upon a psychological stress test (increase in copeptin from 3.7 to 5.1 pmol/L, P = 0.002).29, 30 Increased levels of plasma copeptin were also reported in response to physical exercise, but levels did not exceed the 99th percentile of the normal range.31, 32

Together, these findings emphasize the importance of avoiding emotional or physical stress levels before taking blood samples for copeptin analysis.

2.3. Physiological range of copeptin

The normal range of plasma copeptin levels has been established in two large clinical trials evaluating healthy volunteers under normo‐osmotic conditions. In the first study including 359 subjects, plasma copeptin levels ranged from 1.0 to 13.8 pmol/L with a median concentration of 4.2 pmol/L.13 The second evaluation with over 700 randomly selected volunteers reported comparable results with plasma copeptin levels ranging from 1.0 to 13.0 pmol/L.33 Both trials reported higher median plasma copeptin levels in men than in women, whereas no correlation with age was shown.13, 33 The difference in gender is poorly understood. In an observational study in female volunteers, copeptin levels did not significantly change during the menstrual cycle. However, throughout the menstrual cycle, changes in estradiol were positively related to copeptin, whereas changes in other sex hormones, in markers of subclinical inflammation or in bio impedance analysis‐estimated body fluid were not.34 Interestingly, the gender differences are lost upon hypertonic saline infusion.23

While copeptin levels show no significant variation in response to circadian rhythm35, 36 or digestion, levels significantly decreased from 4.9 to 3.2 pmol/L after oral fluid intake of as little as 200‐300 mL,37 which has to be considered for interpretation of values in clinical practice.

2.4. Measurement of copeptin

In contrast to AVP, copeptin can be measured in clinical routine with commercially available assays with high‐standard technical performance. The two main assays that are currently commercially available and are CE zertified are on one hand the original manual sandwich immunoluminometric assay (LIA)13 and on the other hand the automated immunofluorescent successor (on the KRYPTOR platform). Correlation between with these two assays is very high. Other commercially available copeptin assays are mostly ELISA assays which, however, do not have CE certification and are not approved for diagnostic purposes. Advantages of copeptin over AVP measurement are that only a small sample volume (50 μL of serum or plasma) is required, no extraction step or other pre‐analytical procedures are needed and that results are usually available in 0.5‐2.5 hours. Copeptin is very stable in plasma or serum ex vivo with <20% loss of recovery for at least 7 days at room temperature and for 14 days at 4°C, which makes the handling of blood samples less complicated.

3. THE ROLE OF COPEPTIN IN THE DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF DIABETES INSIPIDUS

3.1. Polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome

Polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome is a common problem in clinical practice with the main entities being central or nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and primary polydipsia.38

While central diabetes insipidus is characterized by a complete (complete central diabetes insipidus) or partial (partial central diabetes insipidus) insufficient vasopressin (AVP) secretion from the pituitary,39, 40 nephrogenic diabetes insipidus results from an AVP resistance of the kidneys41 both leading to hypotonic polyuria with compensatory polydipsia. Central diabetes insipidus can result from various conditions affecting the hypothalamic‐neurohypophyseal system such as trauma resulting from surgery or accident, local tumours or metastases, inflammatory/autoimmune or granulomatous diseases.1, 42 Several reports also described genetic defects in the AVP synthesis leading to inherited forms of central diabetes insipidus.20, 43 The most challenging form of central diabetes insipidus involves an impairment of the thirst perception and consecutive hypodipsia, which can result in severe hypernatremia.38, 44

Nephrogenic diabetes insipidus results from a lack of aquaporin 2 (AQP2)‐mediated water reabsorption in the collecting duct. This is either a consequence of gene mutations in the key proteins vasopressin V2 receptor or AQP2, is secondarily triggered by electrolyte disorders or is induced by certain drugs especially lithium.41

The pathomechanism of primary polydipsia, which is characterized by excessive fluid intake, is less clear. An analysis of 23 patients with profound hyponatraemia due to primary polydipsia revealed an increased prevalence for psychiatric diagnoses such as dependency disorders (43%) and depression (35%).45 Another prospective study with 156 patients with polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome however showed a similar rate (around 30%) of psychiatric disorders in patients with primary polydipsia and patients with central diabetes insipidus.46 As chronic excessive fluid intake in patients with primary polydipsia leads to a down‐regulation of the AQP2 channels in the kidneys, the renal medullary concentration gradient is reduced, making any diagnostic evaluation of the urine osmolality and urinary output difficult.47

Differentiation between the three mentioned entities is important since treatment strategies vary and application of the wrong treatment can be dangerous.48 However, reliable differentiation is often difficult to achieve,49 especially in patients with primary polydipsia or partial forms of diabetes insipidus.2, 50

3.2. Indirect water deprivation test

For decades, the standard diagnostic test for the evaluation of polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome was the indirect water deprivation test.40 Hereby, patients are required to stop any fluid intake from midnight onwards. During the water deprivation period, urinary excretion and urine osmolality as well as plasma sodium and osmolality are measured regularly. Fluid deprivation is continued for a maximum of 17 hours or until a plasma sodium concentration ≥150 mmol/L has been reached or until the patient has lost 3%‐5% of his initial body weight. At this time point, exogenous AVP is administered and the corresponding change in urine osmolality is analysed. Thus, insufficient AVP secretion or effect is indirectly diagnosed by urine osmolality, giving the test the name indirect measurement method. Interpretation of the test results is based on recommendations from Miller et al40 according to the results of 29 patients with central diabetes insipidus (of whom 11 with a partial form), 2 patients with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus and 5 patients with primary polydipsia. Patients showing a urinary osmolality below 300 mosm/kg during the water deprivation test are classified as complete central diabetes insipidus if the urinary osmolality increased >50% after exogenous AVP injection. Patients staying below this cut‐off are diagnosed with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Patients with partial central diabetes insipidus and primary polydipsia are expected to have a urinary osmolality between 300 and 800 mosm/kg upon thirsting. An increase in the urinary osmolality of >9% after AVP administration further differentiates patients with partial central diabetes insipidus from patients with primary polydipsia. However, the proposed cut‐off levels were post hoc derived on a small patient cohort, showed a wide overlap in urinary osmolalities and were never prospectively validated.40

3.3. Direct AVP measurements

Consequently, a recent evaluation of 156 patients with polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome46 pointed out the problems with this diagnostic test, by reaching a diagnostic accuracy (the percentage of correctly diagnosed patients) of only 77% (sensitivity 86%, specificity 70%).

Already in 1981, Zerbe et al51 described a different approach including measurement of plasma AVP upon osmotic stimulation into the diagnostic evaluation (thus called the direct measurement method). In their work, AVP levels were evaluated in relation to the area of normality describing the physiological relationship between AVP release and plasma osmolality. Plasma AVP levels above the area of normality were defined as nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, levels below as central diabetes insipidus and levels in the normal range were defined as primary polydipsia.43, 51 Although the study showed that direct measurement of plasma AVP substantially improved the diagnostic accuracy, it failed to be adopted in clinical practice mainly due to the above‐mentioned inherent assay problems.2, 52

3.4. Direct copeptin measurements

With the development of the copeptin assay,9, 13, 53 interest in the direct measurement arose again. In a first study, Fenske et al aimed to increase the diagnostic accuracy of the water deprivation test by combining it with copeptin measurements.50 In their cohort of 50 patients with polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome, baseline plasma copeptin levels >20 pmol/L diagnosed patients with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, while levels <2.6 pmol/L after an overnight water deprivation test indicated central diabetes insipidus. A ratio of the Δplasma copeptin levels (before and after the water deprivation phase) to the plasma sodium level at the end of the test showed a high diagnostic accuracy of 94% in differentiating patients with central diabetes insipidus from patients with primary polydipsia.50

In an evaluation of 55 patients with nephrogenic or central diabetes insipidus or primary polydipsia, Timper et al54 described copeptin further as a promising new tool for the diagnosis of polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome. This study confirmed in a larger patient number that patients with nephrogenic diabetes insipidus can be easily diagnosed by using a single baseline copeptin level of >21.4 pmol/L without prior thirsting. Baseline copeptin values in the other entities (ie, central diabetes insipidus and primary polydipsia) however largely overlapped. Further, the study showed that osmotically stimulated copeptin levels of >4.9 pmol/L differentiated patients with central diabetes insipidus from patients with primary polydipsia with a high diagnostic accuracy of 96%. Osmotic stimulation was reached by water deprivation and if needed by additional 3% saline infusion aiming at an increase in plasma sodium levels above 147 mmol/L. The evaluation of osmotically stimulated AVP instead of copeptin measurement showed a lower overall diagnostic accuracy of only 80%, and the accuracy was especially low for differentiation between partial central diabetes insipidus and primary polydipsia (44%).

3.5. Hypertonic saline‐stimulated copeptin measurements

The osmotically stimulated copeptin cut‐off level was recently validated in an international multicenter trial including 156 patients with diabetes insipidus or primary polydipsia.46 In contrast to the studies described above, the test protocol was simplified in using only the 3% saline infusion test without prior thirsting. Hypertonic saline was initially given as a bolus dose of 250 mL over 10‐15 minutes, followed by a slower infusion rate of 0.15 mL/kg/min. Plasma sodium and osmolality were measured every 30 minutes, and the infusion was terminated once the plasma sodium was ≥150 mmol/L. At this point, copeptin was measured and the patient was asked to drink water at 30 mL/kg within 30 minutes followed by an intravenous infusion of 5% glucose at 500 mL/h for 1 hour. Plasma sodium was once more measured after completing the 5% glucose infusion to ensure its return to normal values. The diagnostic accuracy of the 3% saline infusion stimulated copeptin measurements was compared to the indirect water deprivation test according to the protocol of Miller et al.40 Further end‐points included the evaluation of copeptin measurements during the water deprivation test.

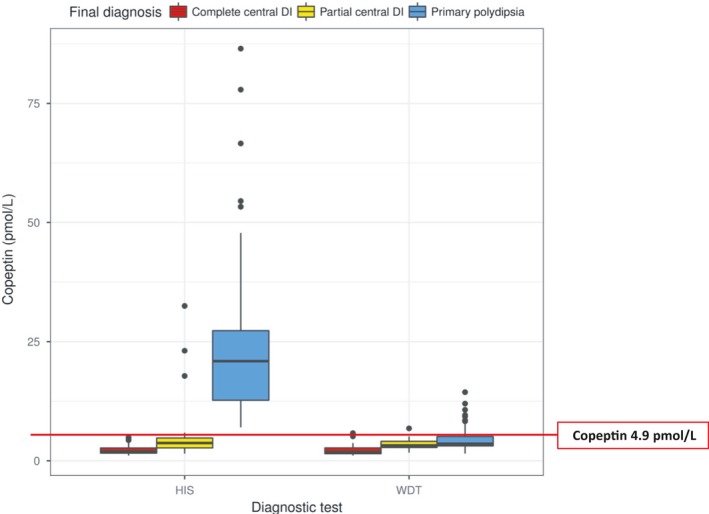

Hypertonic saline infusion lead to a correct diagnosis in 97% (95% CI: 92, 99) of the patients using the copeptin cut‐off level of >4.9 pmol/L (Figure 3), which was clearly superior to the diagnostic accuracy of the indirect water deprivation test of 77% (95%CI: 69, 83; P < 0.001). The diagnostic accuracy of hypertonic saline‐stimulated copeptin was similarly accurate in distinguishing patients with partial diabetes insipidus from patients with primary polydipsia with a correct diagnosis in 95%, compared to 73% with the water deprivation test.

Figure 3.

Stimulated copeptin levels in response to the hypertonic saline infusion and water deprivation test in patients with polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome. Shown are stimulated copeptin levels in response to the hypertonic saline infusion test (HIS) and water deprivation test (WDT) in patients with polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome that was caused by complete central diabetes insipidus (DI) or partial central diabetes insipidus as compared with primary polydipsia. The horizontal line in each box represents the median, the lower and upper boundaries of the boxes the interquartile range, the ends of the whisker lines the minimum and maximum values within 1.5 times the interquartile range, and the dots outliers (modified from Ref.46)

Contrary to the study of Fenske described above, the proposed copeptin‐sodium ratio did not improve diagnostic accuracy of the water deprivation test,50 resulting in a diagnostic accuracy of only 44%.46 The proposed copeptin cut‐off level of <2.6 pmol/L after an overnight water deprivation test to diagnose complete central diabetes insipidus had a diagnostic accuracy of 78%. The fact that the determination of copeptin after water deprivation alone does not lead to an improved diagnostic accuracy is most likely due to the inadequate osmotic stimulation. Indeed, most patients in the study did not reach hyperosmotic plasma sodium levels during the classical water deprivation test.

Accordingly, osmotic stimulation by hypertonic saline solution is needed to obtain reliable copeptin measurements. It is however important to note that hypertonic saline infusion requires close monitoring of sodium levels to ensure increase in plasma sodium levels into the hyperosmotic range22, 39 while preventing osmotic overstimulation.46 It might therefore be prudent for clinical practice to aim at a plasma sodium level >147 mmol/L instead of 150 mmol/L. Also, rapid normalization of sodium levels after the osmotic stimulation is crucial to guarantee the safety of the test.46

Based on these results, the hypertonic saline test plus copeptin measurement might now replace the indirect water deprivation test in the differential diagnosis of polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome55; the recommended new diagnostic workflow algorithm is displayed in Figure 4. Not included in this algorithm are the special cases of diabetes insipidus patients with osmoreceptor dysfunction where thirst is also impaired, and hypodipsia can result in serious complications associated with hyperosmolality. These patients usually develop hypernatremia as they fail to increase their daily fluid intake and therefore do not require additional osmotic stimulation. Copeptin levels can be measured directly to differentiate between central and nephrogenic diabetes insipidus.

Figure 4.

New copeptin‐based diagnostic workflow for the differential diagnosis of polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome [Colour figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com]

3.6. Prediction of postoperative diabetes insipidus

Another role of copeptin is its use as a prognostic marker for the development of diabetes insipidus after pituitary surgery. A first proof‐of‐concept study in 2007 used the classical insulin tolerance test and showed that copeptin measured during hypoglycaemia is a useful measure to identify patients with complete central diabetes insipidus at 3 months after transsphenoidal pituitary surgery.56 In this study, copeptin levels of patients with intact posterior pituitary showed a maximal increase to 11.1 ± 4.6 pmol/L, while copeptin levels in patients with central diabetes insipidus remained low upon hypoglycaemia at 3.7 ± 0.7 pmol/L. A hypoglycaemic stimulated copeptin level <4.75 pmol/L had an optimal diagnostic accuracy to detect central diabetes insipidus of 100%.

Despite its reliable diagnostic performance, the insulin tolerance test is not appropriate in the immediate postoperative recovery phase. Moreover, this test is contraindicated in patients with cardiovascular disease or seizure history. However, surgery—itself known as a stressful event stimulating hypothalamic stress hormone release including AVP,57—can be used as a “stress test” to assess functionality of AVP and copeptin secretion. In a prospective multicentre trial including 205 patients undergoing pituitary surgery, 24% of patients developed postoperative central diabetes insipidus. Those patients had significantly lower copeptin levels on the first postoperative day compared to patients without postoperative diabetes insipidus. The post hoc‐derived copeptin cut‐off level of <2.5 pmol/L had a positive predictive value for the development of central diabetes insipidus of 81% and a specificity of 97%, while a level >30 pmol/L excluded it with a negative predictive value of 95% and a sensitivity of 94%. Accordingly, copeptin measurement after pituitary surgery is helpful to predict the onset of central diabetes insipidus, allowing earlier targeted therapeutic measures.

In conclusion, copeptin is a valuable and reliable diagnostic marker in the differential diagnosis of polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome. In a patient with unclear polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome, determination of basal copeptin levels is recommended to exclude nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. In patients with high suspicion of complete central diabetes insipidus, an overnight water deprivation test might confirm diagnosis provided urine osmolality remains below 300 mosm/kg and plasma sodium levels increase above 147 mmol/L. In all other patients, copeptin measurement after osmotic stimulation with 3% saline solution aiming at a plasma sodium level above 147 mmol/L is recommended (see diagnostic work flow in Figure 4).

The determination of copeptin on the first postoperative day after pituitary surgery is useful to predict the development of central diabetes insipidus.

4. THE ROLE OF COPEPTIN IN THE DIAGNOSIS OF SIAD

4.1. Differential diagnosis of hyponatraemia

Hyponatraemia is defined as a plasma sodium level of <135 mmol/L and characterized by a relative excess of body water compared to total body sodium.3 Although often neglected in clinical practice, hyponatraemia is an important condition as it is present in up to 30% of hospitalized patients4, 58 and linked to increased morbidity, mortality and length of hospital stay.59, 60, 61 Hyponatraemia is associated with a variety of underlying disorders and may be categorized according to extracellular fluid volume into hypervolemic (eg, heart failure, liver cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome), hypovolaemic and euvolemic hyponatraemia with SIAD as the most common cause.62, 63 Main diagnostic criteria for SIAD include plasma osmolality <275 mOsm/kg, urine osmolality >100 mOsm/kg and urine sodium concentration >30 mmol/L, euvolemia and absence of adrenal, thyroid or renal insufficiency.62 Hyponatraemia may further be triggered by diuretic use, primary polydipsia or endocrine conditions (adrenal insufficiency, hypothyroidism). Discrimination between these pathophysiological categories is crucial as management differs considerably (eg, fluid restriction in SIAD vs intravenous fluid in hypovolaemia), and delayed treatment may lead to devastating consequences such as brain oedema, seizures and coma/death.64 Unfortunately, the diagnostic approach to hyponatraemia is complex and time‐consuming; clinical signs and symptoms are variable and unspecific and fluid status is difficult to assess.65, 66 According to current hyponatraemia Clinical Practice Guidelines,62 laboratory measurements such as urine osmolality and urine sodium as well as the calculation of fractional uric acid excretion are proposed; however, in many cases accurate classification into pathophysiological categories remains cumbersome.

4.2. Copeptin in hyponatraemia and SIAD

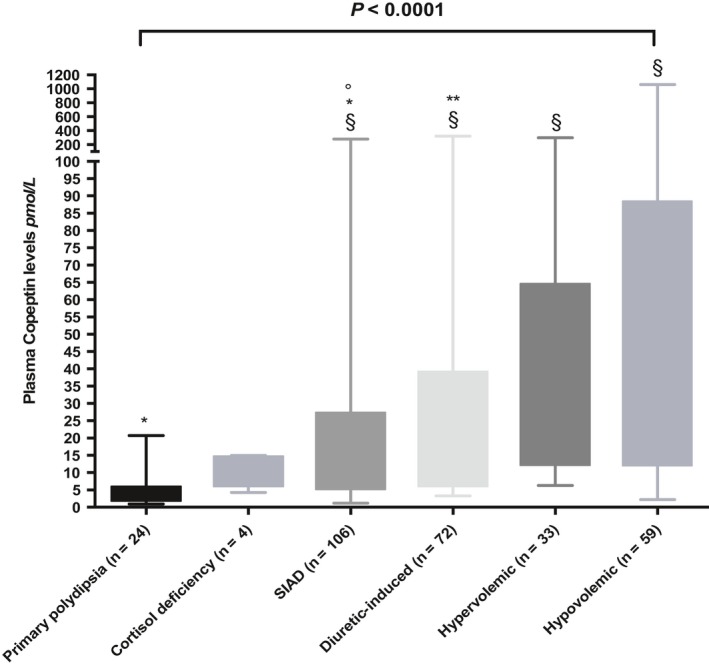

From a pathophysiological point of view, the assessment of AVP or copeptin in hyponatraemia seems promising as most hyponatraemia forms are AVP‐dependent. Copeptin has, therefore, been proposed and evaluated as a readily available and stable diagnostic marker.67, 68, 69 Results from a study involving 106 patients showed no diagnostic utility of copeptin in the differentiation of hyponatraemia, but the ratio of copeptin to urinary sodium helped to discriminate between SIAD and conditions with decreased effective arterial blood volume and, therefore, haemodynamically stimulated AVP release (sensitivity 85%, specificity 87%).68 According to the largest prospective observational study with copeptin measurements in 298 hypoosmolar hyponatraemic patients at hospital admission, clearly elevated copeptin levels as high as >84 pmol/L indicated hypovolaemic hyponatraemia (specificity 90%, sensitivity 23%), whereas low levels <3.9 pmol/L pointed to primary polydipsia (specificity 91%, sensitivity, 58%).69 However, apart from the specificity of highest and lowest values, copeptin measurements were not helpful to differentiate between SIAD and other main causes of hyponatraemia, such as hypovolaemic and hypervolemic or diuretic‐induced hyponatraemia. Indeed, copeptin levels overlapped widely between those categories and showed also a vast variability within single categories, especially in SIAD (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Plasma copeptin levels in different aetiologies of hyponatraemia (modified from Ref.69). Boxplots show median and interquartile range. § P = <0.0001 compared to patients with PP, *P = <0.001 compared to patients with hypervolemic hyponatraemia, **P = <0.05 compared to patients with hypovolaemic hyponatraemia, °P = 0.05 compared to patients with hypervolemic hyponatraemia

4.3. Osmolatory defects in SIAD

Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis is generally characterized by water retention and secondary natriuresis, but its pathophysiology is complex and poorly understood.5 SIAD may arise from a variety of conditions, for example infections, central nervous system disorders, drugs, pain or stress and to an important number also by cancers.70 Other than implied by the originally introduced term “syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH)” by Schwartz and Bartter71 in 1957, this syndrome is not always linked to consistently elevated AVP release. In 1980, Zerbe et al72 first described four types of SIAD according to different osmoregulatory defects. While the first type is characterized by an autonomous, erratic hypersecretion of AVP, they described a preserved linear correlation between AVP and plasma osmolality, but a low osmotic threshold (reset osmostat) in the second type, a constant nonsuppressible AVP leak in the third and a hypovasopressinemic antidiuresis in the fourth type of SIAD patients. In the latter group, no abnormality in AVP secretion could be established and AVP levels were therefore suppressed in the hyponatraemic state, but yet, these patients were not able to dilute their urine.

Later, in 2014 Fenske et al73 analysed serial measurement of copeptin during a hypertonic saline infusion test in SIAD patients. They confirmed the previously suggested subtypes and described a fifth type with linear decrease in copeptin concentrations with increasing plasma osmolality (“barostat reset”; Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Plasma copeptin levels in different subtypes of SIAD (modified from Ref.73) [Colour figure can be viewed at http://www.wileyonlinelibrary.com]

While Zerbe et al could not find an association of one of the osmoregulatory defects and a specific underlying illness, Fenske et al observed that the first type (“subtype A”) was primarily found in patients with lung cancer. The persistently high copeptin values (>38 pmol/L) in these patients may correspond to the long‐standing idea of autonomous extra‐hypothalamic paraneoplastic production of AVP (eg, in lung cancer tissue).74, 75, 76 Based on this observation, one can assume that copeptin might provide a good tool to detect underlying malignancies, which are present in up to a third of SIAD patients according to the Hyponatraemia Registry.77

4.4. Copeptin in cancer‐related SIAD

Our group has recently evaluated data from 146 hospitalized patients with SIAD, of whom 39 were adjudicated to cancer‐related SIAD (unpublished data). Patients with cancer‐related SIAD were predominantly male and of younger age and had significantly higher plasma sodium and urine osmolality levels than patients with nonmalignant SIAD. Interestingly, copeptin levels were not higher in patients with cancer‐related vs cancer‐unrelated SIAD (unpublished data). Although patients with small cell lung cancer tended to have highest copeptin values compared to other cancer entities, copeptin values were not consistently elevated in this cancer subgroup and varied widely both in patient with cancer‐related and cancer‐unrelated SIAD. This can be explained by the fact that hyponatraemia in cancer patients may not only be caused by paraneoplastic AVP secretion, but by any other condition seen in noncancer patients: comorbidities, medication or symptoms as vomiting, nausea, dehydration or stress.78 Of note, irrespective of SIAD, copeptin is known to be elevated due to stress and acute conditions such a pneumonia,79 stroke26 or heart failure.80 The nonosmotic stress‐related copeptin stimulus in acute hospitalized hyponatraemic patients may, therefore, confound the osmotic or paraneoplastic impulse.81, 82

4.5. Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis

Finally, the forth osmoregulatory SIAD subtype (“subtype D”)72, 73—characterized by low or undetectable AVP/copeptin values—may be linked to the nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis,83 although in the study of Fenske et al no gene alteration could be found in the respective patients. This rare syndrome is caused by x‐linked recessive gain of function variants in the AVPR2 gene, which encodes the vasopressin V2 receptor84 or as recently suggested also by a mutation in the GNAS gene.85 In affected male and female patients, the continuous activation of the vasopressin receptor leads to AVP‐independent antidiureses. Consecutively, AVP/copeptin levels are low or suppressed in these patients.85, 86, 87 Management of this disorder includes fluid restriction and avoidance of potential episodes of fluid overload.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, copeptin is a reliable surrogate parameter of AVP. In contrast to AVP, it is stable and can be measured easily with a sandwich immunoassay in serum or plasma. Copeptin is a promising new parameter clearly simplifying the differential diagnosis of polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome. Here, high baseline levels unequivocally indicate nephrogenic diabetes insipidus, and hypertonic saline‐stimulated copeptin levels differentiate between central diabetes insipidus and primary polydipsia with a high sensitivity and specificity. Consequently, hypertonic saline infusion plus copeptin measurement could replace the indirect water deprivation test in the routine evaluation of patients with hypotonic polyuria.

In contrast, in SIAD, copeptin measurement is of only little diagnostic value. Copeptin levels widely overlap in patients with hyponatraemia and emphasize the heterogeneity of the disease. Additionally, a variety of factors leads to unspecific copeptin elevations in the acute setting further complicating its interpretation. The broad use of copeptin as diagnostic marker in hyponatraemia and specifically to detect cancer‐related disease in SIAD patients can, therefore, not be recommended. Nevertheless, extreme values point to a specific underlying pathophysiology: copeptin levels above 84 pmol/L indicate hypovolaemic hyponatraemia and the need for fluid infusion while low levels <3.9 pmol/L are associated with primary polydipsia. Hyponatraemic patients presenting with undetectable copeptin levels and low free water clearance should be investigated for nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Refardt J, Winzeler B, Christ‐Crain M. Copeptin and its role in the diagnosis of diabetes insipidus and the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2019;91:22–32. 10.1111/cen.13991

Funding information

M. Christ‐Crain was supported by a grant from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF‐162608) and the University Hospital Basel, Switzerland.

REFERENCES

- 1. Verbalis JG. Disorders of body water homeostasis. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;17(4):471‐503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robertson GL. Diabetes insipidus. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1995;24(3):549‐572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kumar S, Berl T. Sodium. Lancet. 1998;352(9123):220‐228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Upadhyay A, Jaber BL, Madias NE. Incidence and prevalence of hyponatremia. Am J Med. 2006;119(7 Suppl 1):S30‐S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bartter FC, Schwartz WB. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Am J Med. 1967;42(5):790‐806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Miller M. Syndromes of excess antidiuretic hormone release. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17(1):11‐23, v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kinzie BJ. Management of the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Clin Pharm. 1987;6(8):625‐633. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kluge M, Riedl S, Erhart‐Hofmann B, Hartmann J, Waldhauser F. Improved extraction procedure and RIA for determination of arginine8‐vasopressin in plasma: role of premeasurement sample treatment and reference values in children. Clin Chem. 1999;45(1):98‐103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Balanescu S, Kopp P, Gaskill MB, Morgenthaler NG, Schindler C, Rutishauser J. Correlation of plasma copeptin and vasopressin concentrations in hypo‐, iso‐, and hyperosmolar States. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(4):1046‐1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holwerda DA. A glycopeptide from the posterior lobe of pig pituitaries. I. Isolation and characterization. Eur J Biochem. 1972;28(3):334‐339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Levy B, Chauvet MT, Chauvet J., Acher R. Ontogeny of bovine neurohypophysial hormone precursors. II. Foetal copeptin, the third domain of the vasopressin precursor. Int J Pept Protein Res. 1986;27(3):320‐324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Land H, Schutz G, Schmale H, Richter D. Nucleotide sequence of cloned cDNA encoding bovine arginine vasopressin‐neurophysin II precursor. Nature. 1982;295(5847):299‐303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morgenthaler NG, Struck J, Alonso C, Bergmann A. Assay for the measurement of copeptin, a stable peptide derived from the precursor of vasopressin. Clin Chem. 2006;52(1):112‐119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nathanson MH, Moyer MS, Burgstahler AD, O'Carroll AM, Brownstein MJ, Lolait SJ. Mechanisms of subcellular cytosolic Ca2+ signaling evoked by stimulation of the vasopressin V1a receptor. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(32):23282‐23289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Baylis PH. Osmoregulation and control of vasopressin secretion in healthy humans. Am J Physiol. 1987;253(5 Pt 2):R671‐R678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nagy G, Mulchahey JJ, Smyth DG, Neill JD. The glycopeptide moiety of vasopressin‐neurophysin precursor is neurohypophysial prolactin releasing factor. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1988;151(1):524‐529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hyde JF, North WG, Ben‐Jonathan N. The vasopressin‐associated glycopeptide is not a prolactin‐releasing factor: studies with lactating Brattleboro rats. Endocrinology. 1989;125(1):35‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Barat C, Simpson L, Breslow E. Properties of human vasopressin precursor constructs: inefficient monomer folding in the absence of copeptin as a potential contributor to diabetes insipidus. Biochemistry. 2004;43(25):8191‐8203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Parodi AJ. Protein glucosylation and its role in protein folding. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:69‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Birk J, Friberg MA, Prescianotto‐Baschong C, Spiess M, Rutishauser J. Dominant pro‐vasopressin mutants that cause diabetes insipidus form disulfide‐linked fibrillar aggregates in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Sci. 2009;122(Pt 21):3994‐4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Roussel R, Fezeu L, Marre M, et al. Comparison between copeptin and vasopressin in a population from the community and in people with chronic kidney disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(12):4656‐4663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Robertson GL, Shelton RL, Athar S. The osmoregulation of vasopressin. Kidney Int. 1976;10(1):25‐37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Fenske WK, Schnyder I, Koch G, et al. Release and decay kinetics of copeptin vs AVP in response to osmotic alterations in healthy volunteers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(2):505‐513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Szinnai G, Morgenthaler NG, Berneis K, et al. Changes in plasma copeptin, the c‐terminal portion of arginine vasopressin during water deprivation and excess in healthy subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(10):3973‐3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Morgenthaler NG, Muller B, Struck J, Bergmann A, Redl H, Christ‐Crain M. Copeptin, a stable peptide of the arginine vasopressin precursor, is elevated in hemorrhagic and septic shock. Shock. 2007;28(2):219‐226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Katan M, Fluri F, Morgenthaler NG, et al. Copeptin: a novel, independent prognostic marker in patients with ischemic stroke. Ann Neurol. 2009;66(6):799‐808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reichlin T, Hochholzer W, Stelzig C, et al. Incremental value of copeptin for rapid rule out of acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1):60‐68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Katan M, Christ‐Crain M. The stress hormone copeptin: a new prognostic biomarker in acute illness. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140:w13101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Siegenthaler J, Walti C, Urwyler SA, Schuetz P, Christ‐Crain M. Copeptin concentrations during psychological stress: the PsyCo study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;171(6):737‐742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Urwyler SA, Schuetz P, Sailer C, Christ‐Crain M. Copeptin as a stress marker prior and after a written examination – the CoEXAM study. Stress. 2015;18(1):134‐137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maeder MT, Staub D, Brutsche MH, et al. Copeptin response to clinical maximal exercise tests. Clin Chem. 2010;56(4):674‐676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hew‐Butler T, Hoffman MD, Stuempfle KJ, Rogers IR, Morgenthaler NG, Verbalis JG. Changes in copeptin and bioactive vasopressin in runners with and without hyponatremia. Clin J Sport Med. 2011;21(3):211‐217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bhandari SS, Loke I, Davies JE, Squire IB, Struck J, Ng LL. Gender and renal function influence plasma levels of copeptin in healthy individuals. Clin Sci (Lond). 2009;116(3):257‐263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Puder JJ, Blum CA, Mueller B, De Geyter C, Dye L, Keller U. Menstrual cycle symptoms are associated with changes in low‐grade inflammation. Eur J Clin Invest. 2006;36(1):58‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Darzy KH, Dixit KC, Shalet SM, Morgenthaler NG, Brabant G. Circadian secretion pattern of copeptin, the C‐terminal vasopressin precursor fragment. Clin Chem. 2010;56(7):1190‐1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Beglinger S, Drewe J, Christ‐Crain M.The circadian rhythm of Copeptin, the C‐terminal portion of Arginin Vasopressin. Poster Presentation, SGED Congress Nov 17–18, 2016, Bern, Switzerland. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37. Walti C, Siegenthaler J, Christ‐Crain M. Copeptin levels are independent of ingested nutrient type after standardised meal administration–the CoMEAL study. Biomarkers. 2014;19(7):557‐562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Christ‐Crain M, Fenske W. Copeptin in the diagnosis of vasopressin‐dependent disorders of fluid homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(3):168‐176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Robertson GL. The regulation of vasopressin function in health and disease. Recent Prog Horm Res. 1976;33:333‐385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Miller M, Dalakos T, Moses AM, Fellerman H, Streeten DH. Recognition of partial defects in antidiuretic hormone secretion. Ann Intern Med. 1970;73(5):721‐729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bockenhauer D, Bichet DG. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and management of nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11(10):576‐588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Robertson GL. Differential diagnosis of polyuria. Annu Rev Med. 1988;39:425‐442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Babey M, Kopp P, Robertson GL. Familial forms of diabetes insipidus: clinical and molecular characteristics. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2011;7(12):701‐714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Thompson CJ, Baylis PH. Thirst in diabetes insipidus: clinical relevance of quantitative assessment. Q J Med. 1987;65(246):853‐862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sailer CO, Winzeler B, Nigro N, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with profound hyponatraemia due to primary polydipsia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017;87(5):492‐499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Fenske W, Refardt J, Chifu I, et al. A copeptin‐based approach in the diagnosis of diabetes insipidus. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(5):428‐439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Epstein FH, Kleeman CR, Hendrikx A. The influence of bodily hydration on the renal concentrating process. J Clin Invest. 1957;36(5):629‐634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fenske W, Allolio B. Clinical review: current state and future perspectives in the diagnosis of diabetes insipidus: a clinical review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(10):3426‐3437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Carter AC, Robbins J. The use of hypertonic saline infusions in the differential diagnosis of diabetes insipidus and psychogenic polydipsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1947;7(11):753‐766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Fenske W, Quinkler M, Lorenz D, et al. Copeptin in the differential diagnosis of the polydipsia‐polyuria syndrome–revisiting the direct and indirect water deprivation tests. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(5):1506‐1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Zerbe RL, Robertson GL. A comparison of plasma vasopressin measurements with a standard indirect test in the differential diagnosis of polyuria. N Engl J Med. 1981;305(26):1539‐1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Milles JJ, Spruce B, Baylis PH. A comparison of diagnostic methods to differentiate diabetes insipidus from primary polyuria: a review of 21 patients. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1983;104(4):410‐416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fenske WK, Schnyder I, Koch G, et al. Release and decay kinetics of copeptin versus AVP in response to osmotic alterations in healthy volunteers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(2):505‐513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Timper K, Fenske W, Kuhn F, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of copeptin in the differential diagnosis of the polyuria‐polydipsia syndrome: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(6):2268‐2274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rosen CJ, Ingelfinger JR. A reliable diagnostic test for hypotonic polyuria. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(5):483‐484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Katan M, Morgenthaler NG, Dixit KC, et al. Anterior and posterior pituitary function testing with simultaneous insulin tolerance test and a novel copeptin assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92(7):2640‐2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Widmer IE, Puder JJ, Konig C, et al. Cortisol response in relation to the severity of stress and illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90(8):4579‐4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Upadhyay A, Jaber BL, Madias NE. Epidemiology of hyponatremia. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29(3):227‐238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Waikar SS, Mount DB, Curhan GC. Mortality after hospitalization with mild, moderate, and severe hyponatremia. Am J Med. 2009;122(9):857‐865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Winzeler B, Jeanloz N, Nigro N, et al. Long‐term outcome of profound hyponatremia: a prospective 12 months follow‐up study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2016;175(6):499‐507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Holland‐Bill L, Christiansen CF, Heide‐Jorgensen U, et al. Hyponatremia and mortality risk: a Danish cohort study of 279 508 acutely hospitalized patients. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(1):71‐81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, et al. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014;170(3):G1‐G47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ellison DH, Berl T. Clinical practice. The syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(20):2064‐2072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hyponatremia: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2013;126(10 Suppl 1):S1‐S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Chung HM, Kluge R, Schrier RW, Anderson RJ. Clinical assessment of extracellular fluid volume in hyponatremia. Am J Med. 1987;83(5):905‐908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Fenske W, Maier SK, Blechschmidt A, Allolio B, Störk S. Utility and limitations of the traditional diagnostic approach to hyponatremia: a diagnostic study. Am J Med. 2010;123(7):652‐657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Boursier G, Alméras M, Buthiau D, et al. CT‐pro‐AVP as a tool for assessment of intravascular volume depletion in severe hyponatremia. Clin Biochem. 2015;48(10‐11):640‐645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Fenske W, Störk S, Blechschmidt A, Maier SG, Morgenthaler NG, Allolio B. Copeptin in the differential diagnosis of hyponatremia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(1):123‐129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Nigro N, Winzeler B, Suter‐Widmer I, et al. Evaluation of copeptin and commonly used laboratory parameters for the differential diagnosis of profound hyponatraemia in hospitalized patients: 'The Co‐MED Study'. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2017;86(3):456‐462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Verbalis J, Greenberg A, Burst V, et al. Diagnosing and treating the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion. Am J Med. 2016;129(5):537.e9‐537.e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Schwartz WB, Bennett W, Curelop S, Bartter FC. A syndrome of renal sodium loss and hyponatremia probably resulting from inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone. Am J Med. 1957;23(4):529‐542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zerbe R, Stropes L, Robertson G. Vasopressin function in the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. Annu Rev Med. 1980;31:315‐327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Fenske WK, Christ‐Crain M, Horning A, et al. A copeptin‐based classification of the osmoregulatory defects in the syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(10):2376‐2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Hirata Y, Matsukura S, Imura H, Yakura T, Ihjima S. Two cases of multiple hormone‐producing small cell carcinoma of the lung: coexistence of tumor ADH, ACTH, and beta‐MSH. Cancer. 1976;38(6):2575‐2582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. List AF, Hainsworth JD, Davis BW, Hande KR, Greco FA, Johnson DH. The syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) in small‐cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1986;4(8):1191‐1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sørensen JB, Andersen MK, Hansen HH. Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) in malignant disease. J Intern Med. 1995;238(2):97‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Burst V, Grundmann F, Kubacki T, et al. Euvolemic hyponatremia in cancer patients. Report of the Hyponatremia Registry: an observational multicenter international study. Support Care Cancer. 2017;25(7):2275‐2283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Fiordoliva I, Meletani T, Baleani MG, et al. Managing hyponatremia in lung cancer: latest evidence and clinical implications. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2017;9(11):711‐719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Schuetz P, Wolbers M, Christ‐Crain M, et al. Prohormones for prediction of adverse medical outcome in community‐acquired pneumonia and lower respiratory tract infections. Crit Care. 2010;14(3):R106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Schurtz G, Lamblin N, Bauters C, Goldstein P, Lemesle G. Copeptin in acute coronary syndromes and heart failure management: state of the art and future directions. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;108(6‐7):398‐407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Nigro N, Müller B, Morgenthaler N, et al. The use of copeptin, the stable peptide of the vasopressin precursor, in the differential diagnosis of sodium imbalance in patients with acute diseases. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Jochberger S, Morgenthaler NG, Mayr VD, et al. Copeptin and arginine vasopressin concentrations in critically ill patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(11):4381‐4386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Feldman BJ, Rosenthal SM, Vargas GA, et al. Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(18):1884‐1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Decaux G, Vandergheynst F, Bouko Y, Parma J, Vassart G, Vilain C. Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis in adults: high phenotypic variability in men and women from a large pedigree. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(2):606‐612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Biebermann H, Kleinau G, Schnabel D, et al. A new multisystem disorder caused by the gαs mutation p.F376V. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104(4):1079‐1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Powlson AS, Challis BG, Halsall DJ, Schoenmakers E, Gurnell M. Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis secondary to an activating mutation in the arginine vasopressin receptor AVPR2. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2016;85(2):306‐312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hague J, Casey R, Bruty J, et al. Adult female with symptomatic AVPR2‐related nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis (NSIAD). Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2018;2018: 17-0139. 10.1530/EDM-17-0139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]