Summary

Miniature inverted‐repeat transposable elements (MITEs) are structurally homogeneous non‐autonomous DNA transposons with high copy numbers that play important roles in genome evolution and diversification. Here, we analyzed the rice high‐tillering dwarf (htd) mutant in an advanced backcross population between cultivated and wild rice, and identified an active MITE named miniature Jing (mJing). The mJing element belongs to the PIF/Harbinger superfamily. japonica rice var. Nipponbare and indica var. 93‐11 harbor 72 and 79 mJing family members, respectively, have undergone multiple rounds of amplification bursts during the evolution of Asian cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.). A heterologous transposition experiment in Arabidopsis thaliana indicated that the autonomous element Jing is likely to have provides the transposase needed for mJing mobilization. We identified 297 mJing insertion sites and their presence/absence polymorphism among 71 rice samples through targeted high‐throughput sequencing. The results showed that the copy number of mJing varies dramatically among Asian cultivated rice (O. sativa), its wild ancestor (O. rufipogon), and African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima) and that some mJing insertions are subject to directional selection. These findings suggest that the amplification and removal of mJing elements have played an important role in rice genome evolution and species diversification.

Keywords: amplification, DNA transposon, MITE, targeted high‐throughput sequencing, rice

Significance Statement

An active MITE in rice, named mJing, was identified by analyzing a spontaneous high‐tillering dwarf mutant in an advanced backcross population between cultivated and wild rice. Through targeted high‐throughput sequencing, we identified 297 mJing insertion sites in rice and found that the copy number of mJing varies dramatically among O. sativa, O. rufipogon, and O. glaberrima, suggesting that the amplification of mJing plays an important role in rice genome evolution.

Introduction

Transposable elements (TEs) are major components of many plant and animal genomes and were once regarded as ‘selfish DNA’ or ‘junk DNA’ (Doolittle and Sapienza, 1980; Orgel and Crick, 1980). However, increasing evidence suggests that TEs have made enormous contributions to the evolution of genome structure and the regulation of gene function (Bennetzen et al., 2005; Feschotte, 2008; Rebollo et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013; Bennetzen and Wang, 2014) and have played a major role in the events shaping the genome leading to speciation (Kazazian, 2004). Therefore, understanding the mechanism underlying the origin and amplification of TEs should provide valuable insights into genome evolution and diversification.

Transposable element mobility can lead to genetic diversity, an important source of genetic variation for evolution (Bennett et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2008; Naito et al., 2009; Studer et al., 2011; Huang et al., 2018). TEs are associated with adaptation to temperate climates in Drosophila (González et al., 2010). Aging in social insects is related to TE activity (Elsner et al., 2018), and Alu insertions into exons are generally deleterious and therefore face strong purifying selection in diverse human populations (Witherspoon et al., 2013). Functional variations caused by TE insertions were selected during crop domestication. Insertion of the transposon Hopscotch enhances the expression of the maize (Zea mays) domestication gene tb1, leading to increased apical dominance in maize compared with its wild ancestor, teosinte (Studer et al., 2011). A CACTA‐like transposon within ZmCCT10 and a Harbinger‐like transposon within ZmCCT9 occurred sequentially after the initial domestication of maize and were strongly selected to facilitate the adaptation of maize to higher latitudes (Yang et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2018). A dramatic loss of TEs from the coding regions of genes occurred during rice domestication (Li et al., 2017). Notably, TE‐mediated epigenetic regulation in crops also contributes to phenotypic variation to enhance environmental adaptation and trait improvement (Song and Cao, 2017).

Miniature inverted‐repeat transposable elements (MITEs) are short non‐autonomous Class II elements (100–800 bp) derived from autonomous families via internal deletion (Bureau et al., 1996; Feschotte and Mouchès, 2000; Jiang et al., 2003). MITEs have been identified in a wide range of organisms, including grasses (Bureau and Wessler, 1992), fungi (Yeadon and Catcheside, 1995), insects (Tu, 1997), and humans (Smit, 1996; Smit and Riggs, 1996). MITEs are the most abundant TEs in the rice genome. The MITE insertion has generated numerous polymorphisms, which serve as an ongoing source of genetic variation (Huang et al., 2008). MITEs play important roles in gene regulation and genome evolution, as they preferentially associate with the regulatory regions of rice genes (Lu et al., 2012). MITEs embedded in the regulatory regions of genes can also alter their translation levels. A stowaway‐like MITE insertion in the 3′‐untranslated region of the agronomically important gene Ghd2 directly represses its protein synthesis, affecting grain number, plant height, and heading date in rice (Shen et al., 2017). As a consequence, the effect of MITEs on allelic variation accelerates the evolutionary process.

Although MITEs are widely distributed in plant and animal genomes, to date only a few active MITEs have been identified. In rice, the first active MITE, named miniature Ping (mPing), was identified in a mutant with slender glumes, which harbors an insertion of this element in the slender glume (slg) mutant allele (Nakazaki et al., 2003); this element was also identified through genomic/computational analysis (Jiang et al., 2003; Kikuchi et al., 2003). mPing belongs to the Tourist‐like MITE superfamily and is a perfect deletion derivative of Ping, the autonomous partner responsible for the mobilization of mPing (Jiang et al., 2003). Transposition of mPing can be enhanced by the loss‐of‐function of the Rice ubiquitin‐related modifier 1 (Rurm1) gene and in response to cold and salt stress leading to the upregulation of nearby genes (Naito et al., 2009; Tsukiyama et al., 2013). In addition, three active MITEs, nDart, dTok, and nDaiZ, all belonging to the hAT superfamily, were identified in rice through analysis of the mutability of genes for albinism, multiple pistils, and golden hulls and internodes, respectively (Fujino et al., 2005; Moon et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2009). Finally, mGing, a member of the Gaijing family, can be activated under stress conditions including γ‐ray irradiation and tissue culture (Dong et al., 2012). Therefore, identifying these types of active elements opens up opportunities for understanding the origin and amplification of MITEs.

Here, we identified an active MITE in rice, named miniature Jing (mJing), belonging to the PIF/Harbinger superfamily, as well as the putative autonomous element Jing, which is responsible for the mobilization of mJing. Targeted high‐throughput sequencing showed that the copy number of mJing varies dramatically among Asian cultivated rice (O. sativa), its wild ancestor (O. rufipogon), and African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima), suggesting that the mobilization of mJing elements has played an important role in rice genome evolution and species diversification.

Results

Identification of a spontaneous high‐tillering dwarf mutant in an advanced backcross population between cultivated and wild rice

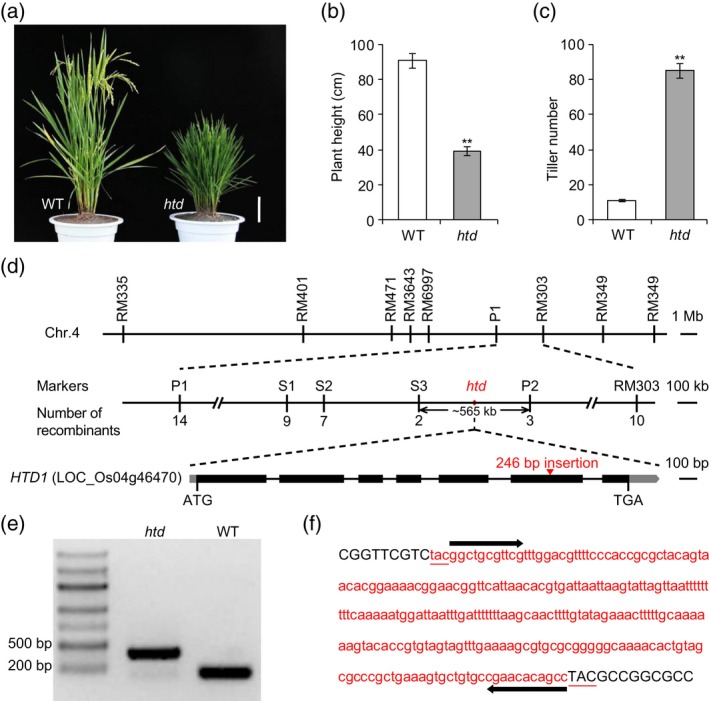

A spontaneous mutant, referred to as high‐tillering dwarf (htd), was identified in an advanced backcross population (BC3) derived from a cross between a perennial wild rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.) accession (YJCWR, Yuanjiang common wild rice) as the donor parent and indica variety Teqing as the recipient parent (also referred to as wild‐type, WT). The htd mutant has significantly reduced plant height, internode length, and grain number and significantly increased tiller number compared with WT (Figures 1a–c and S1). Moreover, htd has reduced grain width, grain thickness, and 1000‐grain weight compared with WT (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

Identification of the miniature inverted‐repeat transposable element miniature Jing (mJing).

(a) Phenotypes of the recipient parent Teqing (wild‐type, WT) and the high‐tillering dwarf (htd) mutant at the heading stage. Scale bars represemt 10 cm.

(b) and (c) Comparison of plant height (b) and tiller number (c) between WT and htd plants at the harvest stage. Values are represented as mean ± SD (n = 20). Two‐tailed Student's t‐tests were performed between WT and htd (**P < 0.01).

(d) Mapping of htd and identification of the candidate mutant gene for the high‐tillering and dwarf phenotypes. The htd gene was mapped to a 565 kb interval on chromosome 4. The number of recombinant plants is shown below the corresponding markers. HTD1 (LOC_Os04g46470) is a strong candidate gene due to the presence of a 246‐bp insertion in its coding region in the htd mutant compared with WT. Black boxes and black lines represent exons and introns, respectively. Gray boxes represent the 5′‐untranslated region (UTR) and 3′‐UTR. The red triangle represents the insertion site.

(e) Validation of the insertion within HTD1 gene by PCR analysis.

(f) Sequences of the 246‐bp insertion and its flanking region. Red lowercase letters and black uppercase letters represent the mJing insertion and the 5′‐ and 3′‐flanking sequences of the mJing insertion in HTD1, respectively. Red underlining and black arrow indicate the target site duplications (TSDs) and terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) of mJing element, respectively.

To identify the HTD gene, we developed a secondary F2 population (204 individuals) derived from a cross between the htd mutant and indica variety Teqing (WT). Phenotypic investigation revealed that the high‐tillering dwarf character is controlled by a single recessive gene (164 WT plants and 40 mutant plants; χ2 = 2.88 < χ2 0.05,1 = 3.84). However, we did not detect polymorphic molecular markers linked to HTD on O. rufipogon introgression segments harbored by the mutant htd allele, suggesting that the causal mutation is present in the genome of the recipient parent. Therefore, we constructed another F2 population (738 individuals) derived from a cross between htd and indica variety 93‐11. Using 150 recessive homozygous plants, htd was delimited to a 565 kb interval between markers S3 and P2 on chromosome 4 (Figure 1d).

Based on annotation information for the rice reference genome (Os‐Nipponbare‐Reference‐IRGSP‐1.0, MSU7), we detected a gene with a known function within the fine‐mapping region of htd. This gene, HIGH‐TILLERING DWARF1 (HTD1, LOC_Os04g46470), encodes carotenoid cleavage dioxygenase, which regulates axillary bud outgrowth (Zou et al., 2006). Hence, HTD1 was a strong candidate for the HTD gene due to the similar phenotypic changes between the htd1 and htd mutants. A sequence comparison of the HTD1 coding region showed that the htd mutant had a 246‐bp insertion in exon 6 relative to the WT (Figure 1d,e), resulting in a premature stop codon and a new htd1 mutated allele (Figure S2). These results suggest that the dysfunction of HTD1 causes the high‐tillering dwarf phenotype of the htd mutant.

Identification of mJing, an active MITE

Nucleotide sequence analysis showed that the 246‐bp insertion in htd1 includes a 3‐bp target site duplication (TSD) of TAC and 11‐bp terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) of 5′‐GGCTGCGTTCG‐3′ (Figure 1f). BLAST analysis using Censor (http://www.girinst.org/, Kohany et al., 2006) revealed that the insertion fragment belongs to the PIF/Harbinger DNA transposon superfamily, suggesting that the insertion is a MITE. Additionally, its TIR sequence does not share high similarity with known MITEs, and therefore we designated the MITE identified in this study as miniature Jing (mJing).

We performed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis using the primer set ID‐6 to assess the presence of the 246‐bp insertion in 955 F4 individuals with high‐tillering dwarf phenotype (15–33 F4 plants from the same F3 individual), which developed from 47 recessive F3 plants harboring the homozygous mJing insertion (mJing +/mJing +). All individuals from two F3 families had only a single 395‐bp PCR product, indicating that the mJing excision did not occur in these individuals (mJing +/mJing +). By contrast, among the 45 other F3 families, at least one individual per F3 family yielded PCR products of two different sizes (mJing +/mJing −) or a single PCR product similar to that of the WT (mJing −/mJing −) (Figure S3 and Table S1). These results suggest that the mJing excision at the htd1 locus occurred in approximately 95.7% (45/47) of the F3 individuals. We further investigated the occurrence of the mJing excision in the F4 through F6 generations using the same approach and found that the frequency of mJing excisions was 94.6%, 87.0%, and 60.0% in the F4–F6 generations, respectively (Figure 2a and Table S1). These results indicate that mJing within the htd1 gene is an active MITE and that the frequency of mJing excision gradually decreases as the generations advance.

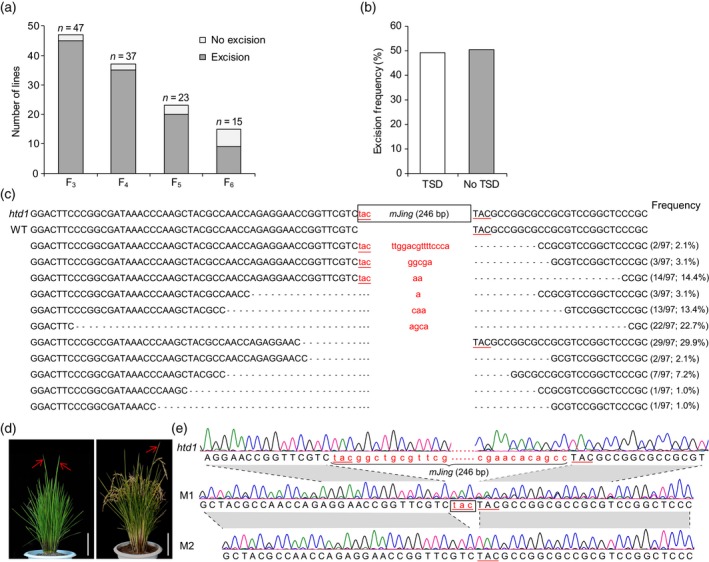

Figure 2.

Excision of mJing within the htd1 mutant allele.

(a) Excision frequency of mJing within the htd1 mutant allele in the F3 through F6 generations. The number of surveyed families in each generation is shown in the histogram.

(b) Frequency comparison of excision with and without perfect TSDs for the 97 independent excision events.

(c) Footprint analysis of the excision at the original site of mJing. The mJing insertion within the htd1 mutant allele is shown in the box. Dashes represent the deleted bases after mJing excision. The numbers in parentheses indicate the proportion of corresponding excision events.

(d) Phenotypes of chimeric mutants at the tillering stage (left) and the maturity stage (right). Red arrows show tillers with partial phenotypic recovery. Scale bar represemts 10 cm. (e) Two types of precise excision events at the original site of mJing in normal tillers of chimeric plants. Chromatograms show the sequences covering the original sites of mJing in dwarf tillers and taller tillers from chimeric plants. M1 and M2 are two normal tillers from different chimeric plants. Gray regions represent those sharing identical sequences. Back box represents the footprint left by mJing excision. In (c) and (e), red lowercase letters represent the mJing insertion, black uppercase letters represent the 5′‐ and 3′‐flanking sequences of the mJing insertion in HTD1, and red underlining indicates the target site duplications (TSDs) of mJing element.

To analyze the footprints generated by mJing excision, we identified 97 independent excision events in F4 individuals using PCR and sequenced the amplicons. Of the 97 excision events, 48 (approximately 49.5%) retained one of the duplicated TSDs (TAC) (Figure 2b). Among these, 19 (19.6%) of the 97 events maintained the 5′ TSD and 29 (29.9%) maintained the 3′ TSD (Figure 2c). Additionally, we detected 11 different footprints at the original site of mJing (Figure 2c). The mJing excision resulted in 6–45‐bp deletions at the 5′ and/or 3′ flanking region and/or 1–15‐bp insertions (Figure 2c). Although the locations of the breakpoints differed between excision events, the nucleotide at the 5′ donor site in all excision footprints was cytidine (C) and in most footprints, the nucleotide at the 3′ acceptor site was cytidine (C, 42/97) or guanine (G, 26/97). In addition, we analyzed the reduced amino acid sequences of the htd1 alleles in which the mJing MITE was imprecisely excised, showing that the mJing excision caused several mutations, including the amino acid deletion, reading frame shift, and premature translation termination (Figure S4a). Therefore, the imprecise excision of mJing at the htd1 locus was not able to rescue the function of HTD1, resulting in individuals with mJing +/mJing − or mJing −/mJing − genotypes that displayed a high‐tillering dwarf phenotype (Figure S4b).

The mJing excision mainly occurred in somatic cells

We examined the excision at the original site of mJing and found that, among the 35 recessive F3 families (35/45, 77.8%), at least one F4 individual per family had a homozygous genotype without the mJing insertion (mJing −/mJing −). Further analysis of the footprints by sequencing the htd1 amplicons showed that the excision patterns of homozygous individuals without the mJing insertion (mJing −/mJing −) were identical to those of heterozygous individuals (mJing +/mJing −) from the same F3 family, implying that the mJing excision detected in F4 individuals mainly occurred in somatic cells of the F3 generation.

Next, we observed the phenotypes of the families with homozygous mJing insertions (mJing +/mJing +) and found that several individuals had one or two tillers of normal height along with dwarf tillers, a characteristic of a chimeric mutant (Figure 2d). PCR analysis showed that the dwarf tillers contained a homozygous mJing insertion (mJing +/mJing +), whereas the taller tillers from the same mutant plants had a heterozygous mJing insertion (mJing +/mJing −). Sequencing of the footprints of mJing excision revealed that the mJing MITE within htd1 was precisely excised in the taller tillers of the chimeric mutants and the entire mJing element and/or TAC duplication was removed leading to the production of normal tillers due to the rescuing of HTD1 gene function (Figure 2e). Taken together, these results suggest that the mJing excision mainly occurred in somatic cells and that the chimeric phenotype for plant height was caused by the precise excision of mJing in somatic cells.

Characteristics of the mJing‐like MITEs in the rice genome

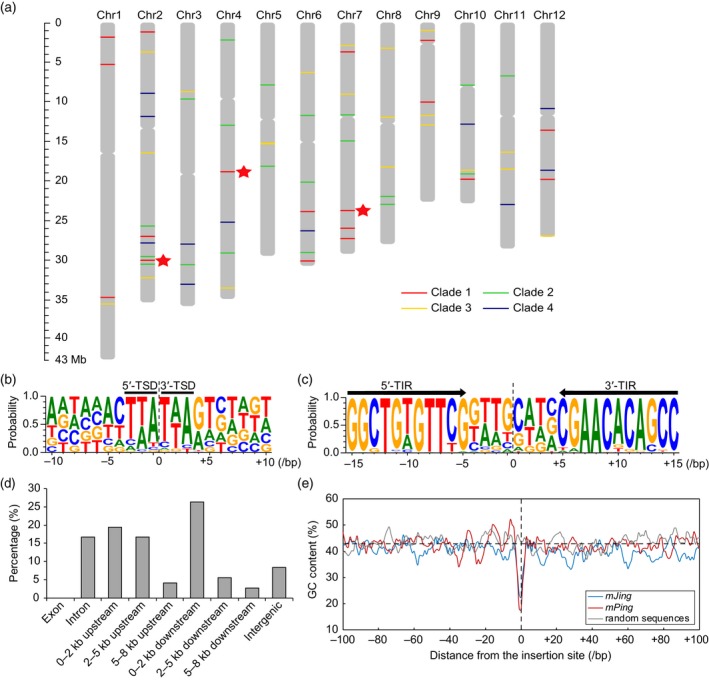

To explore the characteristics of the mJing family in the rice genome, we performed a BLASTN analysis to identify mJing‐like MITEs in the reference genome of O. sativa ssp. japonica var. Nipponbare (Os‐Nipponbare‐Reference‐IRGSP‐1.0, MSU7). We identified 72 mJing‐like MITEs harboring the entire TSD and TIR sequences, which are randomly distributed on the 12 rice chromosomes (Figure 3a and Table S2). Through recovery and alignment of the TSD and TIR sequences of the 72 mJing‐like MITEs, we found that approximately 67.36% of the TSDs were TAA/TTA trinucleotides, whereas 21.53% and 11.11% of the TSDs contained single base or two base changes compared with the TAA/TTA target site sequences, respectively (Figure 3b and Table S3). The 72 mJing‐like MITEs contained a 11‐bp conserved TIR with the sequence 5′‐GGCTGTGTTCG‐3′ (Figure 3c). In the indica var. 93‐11 reference genome, a member of the other subspecies of Asian cultivated rice, we identified 79 mJing family members and found that both the TSD and TIR sequences were similar to those of japonica var. Nipponbare (Figure S5 and Table S4).

Figure 3.

Characteristics of mJing‐like elements in the rice genome.

(a) Distribution of the 72 mJing‐like elements in the japonica var. Nipponbare genome. Different‐colored dashes represent the location of each element belonging to four clades based on phylogenetic analysis of mJing family members, as shown in Figure 4. Red asterisks indicate the three mJing‐like elements with highly similar internal sequences to mJing.

(b, c) Consensus sequences of target site duplications (TSDs) (b) and terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) (c) of the 72 mJing‐like elements in the Nipponbare genome. The size of each letter indicates the frequency of the corresponding nucleotide. Black lines and arrows above the letters indicate the TSDs and TIRs in (b) and (c), respectively.

(d) Insertion preferences of the 72 mJing‐like elements in the Nipponbare genome.

(e) Sliding‐window analysis of GC content within the flanking regions of mJing‐ and mPing‐like elements. Red and blue lines indicate the average GC content in the flanking sequences of mJing‐ and mPing‐like elements, respectively, and the gray line represents that of randomly selected sequences from the Nipponbare genome as a control. The zero on the x‐axis indicates the insertion sites of both mJing‐ and mPing‐like elements.

Investigation of the locations of 72 mJing‐like MITE insertions in the Nipponbare reference genome showed that 12 insertion events (approximately 16.67%) were located in intron regions and 33 events (approximately 45.83%) occurred 2 kb upstream and downstream of gene‐coding regions, whereas no insertion events occurred in exon regions (Figure 3d). The previous study showed that approximately 52.0% of the de novo mPing insertions (133 of 256) were within 3 kb of a coding region (Naito et al., 2006), which is consistent with the characteristics of mJing insertion sites. The results suggested that the insertion of both mJing and mPing elements were preferentially in the flanking region of the gene. Sliding‐window analysis of GC content at the flanking regions of mJing insertions, including 100‐bp up‐ and downstream genome sequences, showed that the flanking regions close to the mJing insertion sites had lower GC contents than those randomly selected 200‐bp genome sequences; this is consistent with the characteristics of mPing family members in rice (Figure 3e) (Naito et al., 2006). Taken together, these results suggest that mJing is preferentially inserted into T/A‐rich regions in the rice genome, especially the 2 kb flanking regions of genes.

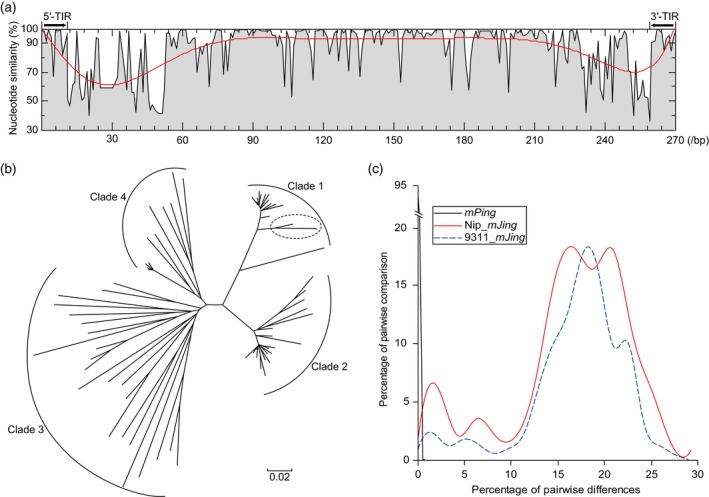

Sequence comparison of the 72 mJing family members revealed that, in addition to their conserved TSD and TIR sequences, mJing family members exhibit significant similarity among their internal sequences, whereas the sequences in the regions neighboring 5′ and 3′ TIRs are more polymorphic (Figure 4a). Phylogenetic analysis of the 72 mJing family members divided these MITEs into four clades (Figure 4b). Among these, Clade 1, comprising 18 mJing‐like MITEs, includes three members (Nip_mJing2.10, Nip_mJing4.3, and Nip_mJing7.6) closest to the mJing MITE identified in this study. To investigate the amplification of mJing family members in the rice genome, we calculated the pairwise nucleotide diversity among the 72 mJing TEs in japonica rice var. Nipponbare genome. The frequency distribution of pairwise nucleotide differences showed a four‐peak distribution that is consistent with the distribution characteristics of mJing family members in the indica var. 93‐11 genome (Figure 4c). By contrast, the mPing family, with 51 members in the Nipponbare genome, had substantially lower nucleotide diversity, and its frequency distribution of pairwise nucleotide differences showed a unimodal distribution (Figure 4c), pointing to different amplification patterns between the mJing and mPing families during rice evolution. Therefore, both phylogenetic and pairwise nucleotide difference analyses demonstrated that multiple rounds of mJing amplification have occurred during rice evolution, and the similar amplification patterns between the indica and japonica subspecies suggest that the amplification of the mJing family might have occurred prior to the indica−japonica differentiation.

Figure 4.

Sequence variation and amplification of mJing‐like elements in rice.

(a) Analysis of sequence similarity among the 72 mJing‐like elements in the Nipponbare genome. Sequence similarity at each site was calculated based on sequence alignment via MUSCLE. Red curve represents the line of best fit for sequence similarity.

(b) Phylogenetic analysis of the 72 mJing‐like elements in the Nipponbare genome. The black dotted oval represents the three family members (Nip_mJing2.10, Nip_mJing4.3, and Nip_mJing7.6) closest to mJing.

(c) Frequency distribution of pairwise nucleotide diversity among mJing and mPing family members in rice, respectively. Black and red lines indicate mPing‐like and mJing‐like elements in the japonica var. Nipponbare genome, respectively. Blue dashed line indicates mJing‐like elements in the indica var. 93‐11 genome.

Identifying the putative autonomous element of mJing

The mJing MITE is a non‐autonomous element, implying that it has no capacity to encode an active transposase. Therefore, we reasoned that the transposition of mJing is catalyzed by a transposase encoded by its corresponding autonomous elements. To identify the corresponding autonomous elements of mJing, we used the mJing sequence to query the indica var. 93‐11 reference genomic with the MAK program (Yang and Hall, 2003a) and obtained more than 8000 high‐similarity sequences. We then selected 205 sequences that were >170 bp with an E‐value <10−20 and recovered the 10 kb upstream and downstream sequences surrounding the target sequences to manually identify the putative autonomous elements of mJing. We identified a putative autonomous element, referred to as Jing, located on chromosome 11 (19 319 940–19 323 561 bp) in the indica var. 93‐11 genome. BLASTN analysis revealed that three copies of the autonomous element Jing are present in the japonica var. Nipponbare genome, which are located on chromosome 2 (4 549 522–4 553 106 bp), chromosome 6 (22 387 549–22 391 278 bp), and chromosome 11 (22 941 196–22 944 833 bp).

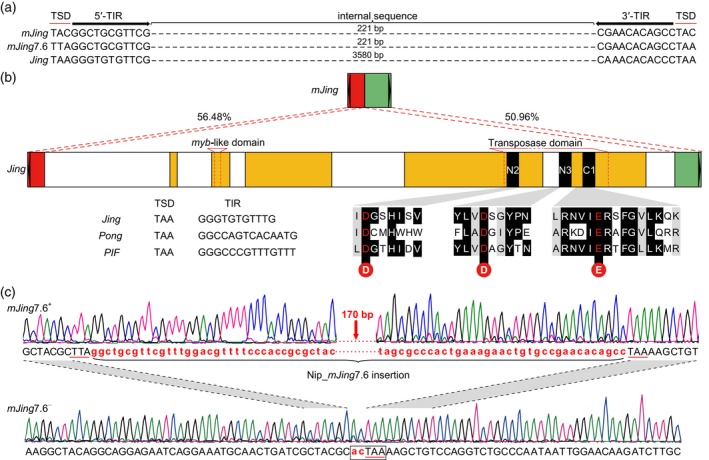

The autonomous element Jing is 3608‐bp long, including a 3‐bp TSD of TAA and an 11‐bp TIR (GGGTGTGTTTG) in the indica var. 93‐11 genome (Figure 5a). Although the sequence identity at the 5′ and 3′ sub‐terminal regions between mJing and Jing is 56.48 and 50.96%, respectively, both the TSD and TIR sequences of Jing are highly similar to those of mJing identified in this study, and six mJing TEs in the Nipponbare genome and seven in the 93‐11 genome shared identical TIR sequences with Jing. Therefore, we reasoned that Jing is most likely to be the autonomous partner of mJing. Gene annotation using FGENESH (http://linux1.softberry.com/berry.phtml) showed that Jing contains a 1803‐bp open reading frame encoding 600 amino acid residues with an myb‐like domain and a transposase domain (Figure 5b). Notably, the transposase domain also possesses a putative DDE motif (referred to as N2, N3, and C1) as its catalytic functional domain (Yuan and Wessler, 2011); this domain contains three highly conserved acidic amino acids (Asp−Asp−Glu) among Jing and Pong in rice and PIF in maize (Jiang et al., 2003) (Figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Identification of the putative autonomous element, Jing.

(a) Sequence comparison of TSDs and TIRs among mJing, NIP_mJing7.6, and Jing elements. Red lines and black arrows above the bases represent TSDs and TIRs, respectively. Dashes represent the internal sequences of each element.

(b) Comparison of mJing and Jing elements. Black triangles represent TIRs. Red and green boxes indicate the 5′ and 3′ regions with high sequence similarity between mJing and Jing, and the numbers show nucleotide identity. Yellow boxes represent exons, and N2, N3, and C1 represent putative catalytic domains. Nucleotide sequences of the TSDs and TIRs and alignment of conserved domains with the DDE motifs of rice Jing, Pong, and maize PIF elements are shown.

(c) The detection of mJing excision in transgenic Arabidopsis plants carrying both mJing7.6 and Jing via Sanger sequencing. mJing7.6− represents a transgenic plant in which the mJing7.6 element was excised, while mJing7.6+ represents a transgenic plant containing an entire mJing7.6 element. Black uppercase letters and red lowercase letters below the chromatogram represent the 5′‐ and 3′‐flanking and internal sequences of mJing7.6, respectively. Red lines above the bases represent TSDs. Black box represents the TSD of Nip‐mJing7.6 and its footprint after excision.

To determine whether Jing drives the transposition of mJing, we developed two constructs for transformation in Arabidopsis thaliana. The construct p35S::Jing harbors a genome fragment including the entire open reading frame of Jing controlled by the Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (CaMV 35S), and the other construct pmJing7.6 carries a 2280‐bp genomic fragment surrounding mJing Nip_mJing7.6 from japonica var. Nipponbare, which is closest to mJing identified in this study. We simultaneously introduced both constructs into Arabidopsis and obtained 12 independent co‐transformed transgenic plants (Figure S6). PCR analysis showed that mJing7.6 was excised from one transgenic plant. Excision footprint analysis showed that, except for one 3′ TSD (TAA) and two nucleotides from the internal sequence, the mJing element was removed at the original site of mJing7.6 (Figure 5c). Taken together, our findings support the notion that the Jing element was likely to have provided the source of transposase for mJing.

Amplification and selection of mJing in wild and cultivated rice

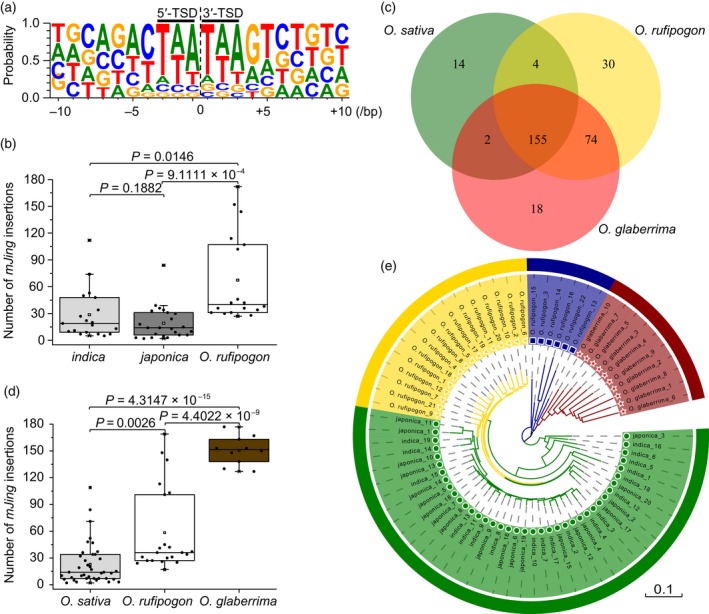

To investigate the amplification and genome distribution of mJing in wild and cultivated rice, we conducted targeted high‐throughput sequencing to detect the mJing insertion sites in various cultivated and wild rice genomes. Because the target probes were designed based on the 5′ and 3′ sub‐terminal regions of mJing, which shared low similarity among family members, elements sharing highly similar sequences to mJing could be enriched. For example, in japonica var. Nipponbare, targeted high‐throughput sequencing detected three insertion events (Nip_mJing2.10, Nip_mJing4.3 and Nip_mJing7.6) with the highest sequence similarity to mJing among all mJing family members in the Nipponbare genome identified in this study. Through targeted high‐throughput sequencing, we identified 297 mJing insertion sites among all rice samples examined including 19 indica varieties, 20 japonica varieties, 22 O. rufipogon accessions, and 10 varieties of African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima) (Table S5); some mJing‐specific and/or unique insertions were verified by PCR (Figure S7). The 297 mJing insertions are distributed on the 12 rice chromosomes (Figure S8a), and the TSD sequences and insertion positions of the 297 mJing elements share similar characteristics with mJing family members in the Nipponbare reference genome (Figures 6a, S7b and Table S6). Interestingly, although approximately 47.81% (142/297) of the insertion events occurred in the 2 kb upstream and downstream sequences of gene‐coding regions, 6.06% (18/297) and 5.05% (15/297) insertions occurred in the intron and exon regions of functional genes, respectively (Figure S8b and Table S7), indicating that these mJing insertions might directly affect gene function.

Figure 6.

Amplification and selection of mJing‐like elements in wild and cultivated rice.

(a) Consensus sequences of target site duplications (TSDs) of the 297 mJing elements in the rice genome. The letter size represents the frequency of the corresponding nucleotide. Black lines above the letters indicate TSDs.

(b) Comparison of the number of mJing insertions among indica, japonica, and O. rufipogon. Black dots represent the number of mJing insertions in each sample. Two‐tailed Student's t‐tests were performed.

(c) Venn diagrams showing the number of unique and common mJing insertions among O. sativa, O. rufipogon, and O. glaberrima.

(d) Comparison of the number of mJing insertions among O. sativa, O. rufipogon, and O. glaberrima. Black dots represent the number of mJing insertions in each sample. Two‐tailed Student's t‐tests were performed.

(e) Phylogenetic analysis based on the polymorphism of 297 mJing‐like elements in 71 accessions of wild and cultivated rice. Green represents Asian cultivated rice (O. sativa) varieties, including indica and japonica subspecies. Yellow and blue represent O. rufipogon accessions that are more and less closely related to cultivated rice, respectively. Red represents African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima) varieties.

Differences in the copy numbers of mJing between wild and cultivated rice might also reflect the amplification and selection of this MITE during rice evolution. We found that the copy number of mJing varied dramatically among the rice accessions examined, ranging from 2 to 177 members. The average copy number of mJing in the O. rufipogon genome was 58.3, which is significantly higher than that in indica (28.2) and japonica (18.1) rice (Figure 6b and Table S5). These results suggest that some mJing insertions with unfavorable genetic effects might have been removed during rice domestication. Additionally, although O. sativa shares 160 of 297 insertion sites with O. rufipogon, 104 and 16 unique insertion sites were detected in the O. rufipogon and O. sativa genomes (Figure 6c), respectively, suggesting that the mJing element maintained transpositional activation after the differentiation of wild and cultivated rice. Interestingly, the average copy number (150.6) of the mJing element in African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima) was dramatically higher than that in Asian cultivated (O. sativa) and wild rice (O. rufipogon) (Figure 6d), implying that the amplification of mJing might have played an important role in the evolution of Asian and African rice accessions with AA genomes.

Based on the polymorphisms (presence/absence) of 297 mJing MITEs (Table S5), our phylogenetic analysis divided the 71 rice samples into four divergent group, including one group of Asian cultivated rice, two groups of O. rufipogon accessions, and one African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima) group (Figure 6e). We calculated the fixation index (F ST) of each mJing locus between indica and japonica, between O. sativa and O. rufipogon, and between O. rufipogon and O. glaberrima. No obvious locus differentiation was detected between indica and japonica rice, whereas the F ST values at 14 and 126 mJing loci were >0.25 between O. sativa and O. rufipogon and between O. rufipogon and O. glaberrima (Table 1). These results suggest that some mJing loci were directionally selected during rice evolution.

Table 1.

Estimated fixation index (F ST) values of the 297 mJing insertions in rice

| Population | F ST | Number of insertions | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Between subspecies japonica and indica | <0.05 | 136 | 78.16 |

| 0.05–0.15 | 34 | 19.54 | |

| 0.15–0.25 | 4 | 2.30 | |

| >0.25 | 0 | 0 | |

| Between O. rufipogon and O. sativa | <0.05 | 165 | 59.35 |

| 0.05–0.15 | 85 | 30.57 | |

| 0.15–0.25 | 14 | 5.04 | |

| >0.25 | 14 | 5.04 | |

| Between O. rufipogon and O. glaberrima | <0.05 | 109 | 38.79 |

| 0.05–0.15 | 24 | 8.54 | |

| 0.15–0.25 | 22 | 7.83 | |

| >0.25 | 126 | 44.84 |

Discussion

MITEs are widespread among eukaryotic genomes and play important roles in genome evolution and gene regulation. Previous studies have revealed the mechanisms underlying the emergence, spread, and disappearance of MITEs through the identification and characterization of active MITEs. Here, we identified an active MITE, mJing, by analyzing a spontaneous high‐tillering dwarf mutant obtained from an advanced backcross population from wild and cultivated rice. We also detected the de novo insertion sites of mJing in 14 F5 individuals, in which the mJing element was excised at the htd1 locus, through the targeted high‐throughput sequencing. We found nine de novo insertion sites in the F5 individuals, indicating that a majority of elements excised may move to another site in the rice genome (Table S8). Additionally, both the TIRs and internal sequences of mJing are dramatically different from those of mPing, a previously identified active MITE in the rice genome, although the mJing and mPing elements share similar TSD sequences and belong to the PIF/Harbinger superfamily. Therefore, the identification of the mJing element provides opportunities to investigate the contribution of MITEs to the evolution of the rice genome.

TE activity is enhanced by biotic and abiotic stresses such as pathogen infection, γ‐irradiation, hydrostatic pressurization, and tissue culture (Orgel and Crick, 1980; Nakazaki et al., 2003; Xu et al., 2004; Lin et al., 2006). The dramatic difference in copy number of mPing between the two subspecies of rice, japonica and indica, suggests that, during rice domestication, extreme environmental conditions might have promoted the mobilization of mPing (Jiang et al., 2003). Indeed, the mobilization of mPing was detected in recombinant inbred lines derived from introgressive hybridization between O. sativa and Zizania latifolia (Shan et al., 2005). In addition to identifying an active MITE in the hybrid progenies of wild and cultivated rice, we performed targeted high‐throughput sequencing to analyze the mJing insertion in 10 wild rice introgression lines (Ma et al., 2016). We detected two de novo insertions (Table S9), suggesting that the mobilization of mJing might be induced by distance hybridization between wild (O. rufipogon) and cultivated (O. sativa) rice. This finding provides evidence to support the hypothesis that TEs are activated by ‘genomic shock’ due to plant‐wide hybridization (McClintock, 1984). Notably, the previous study demonstrated that mPing might have stimulated the loss‐of‐function of the Rurm1 gene, supporting one of the models of genome shock theory that the endogenous stress enhances the transposition activity of TEs (Tsukiyama et al., 2013).

Because MITEs are non‐autonomous DNA elements that do not encode transposases, the mobilization of MITEs relies on the presence of transposase encoded by their cognate autonomous elements. In plants, most MITEs were likely to have derived from two DNA element superfamilies, PIF/Harbinger and Tc1/Mariner elements, which are classified as either Tourist‐like or Stowaway‐like elements (Feschotte et al., 2002). The Tourist‐like MITE mPing is a perfect deletion derivative of Ping, which belongs to the PIF/Harbinger superfamily and provides the source of transposase for mPing (Jiang et al., 2003). Unlike mPing, although Stowaway‐like MITEs are not deletion derivatives of Tc1/Mariner elements, the transposition of Stowaway MITEs is catalyzed by transposases encoded by Tc1/Mariner elements, demonstrating that transposases from distantly related elements play an important role in the movement of non‐deletion derivative MITEs (Feschotte et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2009). In addition, many MITEs are likely to have originated from members of the En/Spm and Mutator superfamilies, as evidenced by their shared TIR and TSD sequences (Wicker et al., 2003; Yang and Hall, 2003a,b).

Based on the current results, we hypothesize that, in rice, the Jing element is the source of the transposase for mJing, as revealed by the strong similarity of the TSD and TIR sequences between Jing and mJing. Furthermore, a heterologous transposition experiment showed that mJing can be excised by the transposase encoded by Jing. However, the sequence similarity in the sub‐terminal regions of mJing and Jing is lower than that between mPing and Ping. Therefore, we hypothesize that mJing might not be a deletion derivative of the existing autonomous element Jing but instead, the mJing element is likely to be mobilized by ‘borrowing’ a transposase from Jing, a distantly related autonomous element. Another hypothesis is that mJing is a deletion derivative of Jing, but the sequences in the sub‐terminal regions of mJing might have been altered during multiple rounds of amplification. Therefore, further investigations of the autonomous partner of mJing in rice or other plants including its evolutionary process would be valuable for understanding the mechanisms underlying the emergence, spread, and disappearance of MITEs.

The nucleotide diversity between elements from the same MITE family might reflect the amplification characteristics of MITEs during genome evolution. A study of the pairwise nucleotide diversity of full‐length elements from 37 MITE families in rice revealed the occurrence of different patterns of amplification bursts during rice evolutionary history (Lu et al., 2012). The japonica var. Nipponbare reference genome contains 51 members of the mPing family with high nucleotide similarity, implying that this family has undergone one round of rapid amplification. By contrast, the mJing family has 72 members with low nucleotide similarity in their 5′ and 3′ sub‐terminal regions, suggesting that this family experienced multiple rounds of amplification during rice evolutionary history. In addition, the average pairwise nucleotide diversity is higher for mJing versus mPing elements indicating that the amplification of mJing elements occurred before mPing amplification during rice genome evolution. Altogether, these results suggest that single or multiple rounds of amplification of these MITE families might have occurred during different periods of rice evolution.

Targeted high‐throughput sequencing is an efficient method for identifying the insertion positions of specific transposon elements in the genome. In the present study, we identified 297 mJing insertions in 71 rice samples through targeted high‐throughput sequencing. Notably, because the genome fragments were enriched via DNA hybridization, the insertions that were identified by targeted high‐throughput sequencing share highly sequence similarity with the mJing insertion in HTD1. In japonica var. Nipponbare, only three mJing family members with high sequence similarity to mJing in HTD1 were detected, while in O. rufipogon accession YJCWR, 169 mJing family members were detected indicating that the copy number of mJing varies dramatically in cultivated versus wild rice. Subsequently, we found that the average copy number of mJing significantly differed between Asian cultivated rice (O. sativa) and its wild ancestor O. rufipogon and between O. rufipogon and African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima). African cultivated rice had the highest copy number (average of 150.6), while Asian cultivated rice had the lowest (average of 23.2) among the three species surveyed. In addition, 14 and 126 mJing loci might have undergone directional selection during the differentiation between O. sativa and O. rufipogon and between O. rufipogon and O. glaberrima, respectively. However, no obvious locus differentiation was detected between the two subspecies of Asian cultivated rice, indica and japonica. Whether environmental adaptation or purifying selection is associated with the variation in mJing copy number in the divergent rice genomes requires further investigation. Therefore, our identification of an active MITE mJing provides opportunities for investigating the roles of MITEs during rice evolution.

Experimental procedures

Plant materials

The high‐tillering dwarf (htd) mutant was identified from an advanced backcross population (BC3) derived from a cross between O. rufipogon accession YJCWR from Yuanjiang county, Yunnan Province, China, as the donor parent and indica rice variety Teqing (O. sativa ssp. indica) as the recipient parent (Tan et al., 2008). To map the gene for the high‐tillering, dwarf phenotype, an F2 population was developed from a cross between indica variety 93‐11 and the htd mutant. To investigate the amplification and genome distribution of mJing, 71 rice samples including 19 indica varieties, 20 japonica varieties, 22 O. rufipogon accessions, and 10 varieties of African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima) were used for targeted high‐throughput sequencing (Table S5).

Phenotypic evaluation

Twenty plants each of the htd1 mutant and recipient parent Teqing (WT) were examined to measure plant height, tiller number, internode length, grain length, grain width, and grain thickness.

Footprint analysis of mJing excision within HTD1

Genomic DNA was extracted from 97 independent lines from the F4 populations and used for PCR analysis of mJing within the HTD1 gene. Primers 6ID‐F and 6ID‐R were used to detect the insertion and excision of mJing. One homozygous (mJing −/mJing −) or heterozygous (mJing +/mJing −) individual per line was selected to analyze the mJing footprint based on analysis of the PCR products. The excision of mJing was confirmed by PCR amplification using the primer set Osmax6, and the PCR products were directly sequenced.

Identification of an mJing‐like element in the rice reference genome

Both the japonica var. Nipponbare (Os‐Nipponbare‐Reference‐IRGSP‐1.0, MSU7) and indica var. 93‐11 (ASM465v1) reference genome sequences were downloaded from the Ensembl site (http://plants.ensembl.org/info/website/ftp/index.html). A local BLAST search was performed using the 243‐bp mJing element as a query with the following settings: length >120 bp and E‐value <10−27. If the length of the target sequence was <220 bp, its upstream and downstream sequences were extended until the 5′‐ and 3′‐TIRs appeared in the reference genome. In total, 72 and 79 full‐length mJing‐like elements were discovered in Nipponbare and 93‐11, respectively. Information about all of the mJing‐like elements is provided in Tables [Link], [Link], [Link].

Characterization of mJing‐like elements in the rice reference genome

The consensus TSD and TIR sequences of mJing‐like elements in the rice genome were depicted using WebLogo 3.0 (Crooks et al., 2004). To analyze the insertion preference of mJing, the 100‐bp upstream and downstream sequences of the 72 mJing‐like and 51 mPing‐like insertion sites (including TSD sequences), respectively, were extracted from the Nipponbare genome. Furthermore, 72 200‐bp long sites were randomly selected from the Nipponbare genome as a control. The GC content was calculated for each 5‐bp sliding‐window at a 1‐bp increment. To investigate the association of mJing‐like elements and genes in the rice genome, the locations of mJing insertions were investigated, and based on the distance between the insertion site and the annotated genes, the insertion position was categorized as being in an exon or intron, upstream or downstream of a gene‐coding region, or in intergenic regions (>8 kb from a gene). Pairwise diversity among members of the mPing and mJing families in the Nipponbare genome was calculated using a Perl script (each gap was considered to be a single mismatch), and the frequency distribution of pairwise nucleotide diversity was used to describe the amplification event during genome evolution.

Transposition assay

A 2280‐bp genomic fragment harboring the entire Nip_mJing 7.6 sequence with the 986‐bp 5′‐flanking region and 1051‐bp 3′‐flanking region was obtained through PCR amplification and inserted into the pCAMBIA1300 binary vector to generate the construct pmJing7.6. The p35S::Jing construct harbored a genome fragment containing the entire gene‐coding region (1803 bp from ATG to TAG) of Jing controlled by the Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (CaMV 35S). Both constructs were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3103, followed by co‐transformation into Arabidopsis thaliana (Columbia ecotype). Transgenic plants were selected on Murashige and Skoog (MS) solid medium (0.7% (w/v) Phytagel) containing 30 mg L−1 hygromycin B. PCR analysis was performed using primer sets D_pmJing7.6‐2 and D_p35S::Jing to detect positive co‐transformed transgenic plants, respectively, and the amplicons were sequenced to analyze the footprint of the mJing7.6 excision.

Targeted high‐throughput sequencing

Illumina sequencing libraries were constructed for targeted high‐throughput sequencing as described by Williams‐Carrier et al. (2010), with minor modifications. Genomic DNA was extracted using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) method and treated with ribonuclease A (37°C) and proteinase K (42°C) for 1 h. Genomic DNA was sheared into approximately 400–500‐bp fragments by sonication (set to 15 sec on and 45 sec off and sonicated for 10 min). Modified adapters (Table S10) were ligated to the DNA fragments. DNA fragments containing mJing were enriched by hybridization to two biotinylated 40‐bp oligonucleotides of mJing, including the 11‐bp 5′‐TIR and its neighboring 29‐bp sub‐terminal sequence and the 11‐bp 3′‐TIR and its neighboring 29‐bp sub‐terminal sequence (Table S10). During PCR amplification to ‘bulk up’ the DNA, a 6‐bp index barcode in the middle of the P7 primers (index1–index64) was used to distinguish the samples (Table S10). Finally, the paired‐end libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq/MiSeq system at Novogene Company (Beijing, China). Approximately 0.1–0.5 G clean data were obtained per sample. The detailed method used for targeted high‐throughput sequencing is depicted in Figure S9.

Sequencing data analysis

Raw reads were processed using Cutadapt (Martin, 2011) for adapter trimming, and quality filtered reads were aligned to the modified Nipponbare sequence (Os‐Nipponbare‐Reference‐IRGSP‐1.0, MSU7), excluding three sequences that are highly similar to mJing (Nip_mJing2.10, Nip_mJing4.3 and Nip_mJing7.6), using Bowtie2 (Langmead and Salzberg, 2012). The PTEMD program (Ye et al., 2009; Kang et al., 2016) was used to identify mJing insertions in the cultivated and wild rice genomes. The output format of PTEMD contained the insertion sites, TSDs, and breakpoints of each mJing insertion (Table S11). The genotypes of all samples were scored based on presence/absence polymorphisms of the mJing insertions. The fixation index (F ST) of each locus was calculated using DnaSP version 5.1 (Librado and Rozas, 2009).

PCR validation of mJing de novo insertions

To validate the specific and/or unique mJing insertions in the cultivated and wild rice genomes, PCR primers were designed based on the flanking sequences of the mJing insertion, and locus‐specific PCR of the mJing insertion sites was performed. The products were separated using polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) in 1% (w/v) agarose gels to distinguish the presence/absence polymorphisms of mJing insertions in the rice genome. The primer sets used to detect the polymorphisms of the mJing insertions are listed in Table S12.

Phylogenetic analysis

The sequences of 72 mJing‐like MITEs in the Nipponbare genome were aligned using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004), and the phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 6.0 and the neighbor‐joining method (Tamura et al., 2013). Based on the presence/absence polymorphisms of 297 mJing insertions, a phylogenetic tree of cultivated and wild rice was constructed using MEGA 6.0 (Tamura et al., 2013) and Evolview (He et al., 2016).

Primers

The primers used in this study are listed in Table S12.

Statistical analysis

Two‐tailed Student's t‐tests were performed using SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Author Contributions

LT and FL conceived and designed the work. YT performed most of the experiments. YT, XM, and XZ completed the bioinformatics analyses of all data. SZ, WX, HS, PG, ZZ, and CQ contributed to rice materials. YT, FL, and LT wrote the paper.

Supporting information

Figure S1. Phenotypes of wild‐type (WT) and htd mutant rice.

Figure S2. Open reading frame (ORF) of HTD1 and deduced amino acid sequences in WT and htd.

Figure S3. Transposition of mJing in a high‐tillering dwarf population.

Figure S4. Changes in amino acid sequence encoded by the htd1 alleles and phenotypes of F4 individuals that have the mJing +/mJing − or mJing −/mJing − genotype.

Figure S5. Consensus sequences of target site duplications (TSDs) and terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) of 79 mJing‐like elements in the indica variety 93‐11 genome.

Figure S6. PCR analysis to detect co‐transformed transgenic plants.

Figure S7. Validation of the mJing insertion identified through targeted high‐throughput sequencing using PCR analysis.

Figure S8. Distribution and insertion preference of 297 mJing‐like elements identified through targeted high‐throughput sequencing.

Figure S9. Flow chart of the method used for targeted high‐throughput sequencing.

Table S1. Analysis of mJing excisions within the htd1 mutant allele in the F3 through F6 generations.

Table S2. Detailed information on 72 mJing‐like elements in the japonica rice variety Nipponbare genome (Os‐Nipponbare‐Reference‐IRGSP‐1.0, MSU7).

Table S3. Characteristics of target site duplications (TSDs) of 72 mJing‐like elements in the japonica variety Nipponbare genome (Os‐Nipponbare‐Reference‐IRGSP‐1.0, MSU7).

Table S4. Detailed information on 79 mJing‐like elements in the indica rice variety 93‐11 genome (ASM465v1).

Table S5. Presence/absence polymorphism of 297 mJing elements in the 71 samples surveyed.

Table S6. Characteristics of target site duplications (TSDs) of 297 mJing elements identified through targeted high‐throughput sequencing.

Table S7. Detailed information on 297 mJing elements identified through targeted high‐throughput sequencing.

Table S8. Information on mJing de novo insertions sites found in nine F5 individuals in which the mJing element was excised at the htd1 locus.

Table S9. Information of mJing de novo insertions found in the wild rice introgression lines.

Table S10. Oligonucleotides used in targeted high‐throughput sequencing.

Table S11. Enriched reads at the mJing insertions identified in japonica rice variety Do Khao (Chr12:25 499 426) and O. rufipogon accession IRGC89140 (Chr1:14 969 394).

Table S12. Primers used in this study.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31671647) and the program for New Century Excellent Talents in University from the Ministry of Education of China (NCET‐12‐0517).

Contributor Information

Fengxia Liu, Email: liufx@cau.edu.cn.

Lubin Tan, Email: tlb9@cau.edu.cn.

Data availability

The GenBank accessions for nucleotide sequences of mJing and Jing identified in this study are MH727588 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MH727588) and MH727589 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MH727589), respectively. Clean data generated in targeted high‐throughput sequencing in this study have been deposited in NCBI's Short Read Archive under the accession PRJNA507518 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA507518).

References

- Bennett, E.A. , Coleman, L.E. , Tsui, C. , Pittard, W.S. and Devine, S.E. (2004) Natural genetic variation caused by transposable elements in humans. Genetics, 168, 933–951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen, J.L. and Wang, H. (2014) The contributions of transposable elements to the structure, function, and evolution of plant genomes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 65, 505–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen, J.L. , Ma, J. and Devos, K.M. (2005) Mechanisms of recent genome size variation in flowering plants. Ann. Bot. 95, 127–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau, T.E. and Wessler, S.R. (1992) Tourist: a large family of small inverted repeat frequently associated with maize genes elements. Plant Cell, 4, 1283–1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau, T.E. , Ronald, P.C. and Wessler, S.R. (1996) A computer‐based systematic survey reveals the predominance of small inverted‐repeat elements in wild‐type rice genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 8524–8529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks, G.E. , Hon, G. , Chandonia, J.M. and Brenner, S.E. (2004) WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 14, 1188–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.T. , Zhang, L. , Zheng, K.L. et al (2012) A Gaijin‐like miniature inverted repeat transposable element is mobilized in rice during cell differentiation. BMC Genom. 13, 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolittle, W.F. and Sapienza, C. (1980) Selfish genes, the phenotype paradigm and genome evolution. Nature, 284, 601–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar, R.C. (2004) MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, 1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, D. , Meusemann, K. and Korb, J. (2018) Longevity and transposon defense, the case of termite reproductives. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 115, 5504–5509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C. (2008) Transposable elements and the evolution of regulatory networks. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C. and Mouchès, C. (2000) Evidence that a family of miniature inverted‐repeat transposable elements (MITEs) from the Arabidopsis thaliana genome has arisen from a pogo‐like DNA transposon. Mol. Biol. Evol. 17, 730–737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C. , Jiang, N. and Wessler, S.R. (2002) Plant transposable elements: where genetics meets genomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 3, 329–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feschotte, C. , Swamy, L. and Wessler, S.R. (2003) Genome‐wide analysis of mariner‐like transposable elements in rice reveals complex relationships with stowaway miniature inverted repeat transposable elements (MITEs). Genetics, 163, 747–758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino, K. , Sekiguchi, H. and Kiguchi, T. (2005) Identification of an active transposon in intact rice plants. Mol. Genet. Genomics, 273, 150–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González, J. , Karasov, T.L. , Messer, P.W. and Petrov, D.A. (2010) Genome‐wide patterns of adaptation to temperate environments associated with transposable elements in Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He, Z. , Zhang, H. , Gao, S. , Lercher, M.J. , Chen, W.H. and Hu, S. (2016) Evolview v2: an online visualization and management tool for customized and annotated phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W236–W241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, X. , Lu, G. , Zhao, Q. , Liu, X. and Han, B. (2008) Genome‐Wide analysis of transposon insertion polymorphisms reveals intraspecific variation in cultivated rice. Plant Physiol. 148, 25–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J. , Zhang, K. , Shen, Y. , Huang, Z. , Li, M. , Tang, D. , Gu, M. and Cheng, Z. (2009) Identification of a high frequency transposon induced by tissue culture, nDaiZ, a member of the hAT family in rice. Genomics, 93, 274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. , Sun, H. , Xu, D. et al (2018) ZmCCT9 enhances maize adaptation to higher latitudes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 115, E334–E341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, N. , Bao, Z. , Zhang, X. , Hirochika, H. , Eddy, S.R. , McCouch, S.R. and Wessler, S.R. (2003) An active DNA transposon family in rice. Nature, 421, 163–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H. , Zhu, D. , Lin, R. , Opiyo, S.O. , Jiang, N. , Shiu, S.H. and Wang, G.L. (2016) A novel method for identifying polymorphic transposable elements via scanning of high‐throughput short reads. DNA Res. 23, 241–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazazian, H.H. Jr (2004) Mobile elements: drivers of genome evolution. Science, 303, 1626–1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, K. , Terauchi, K. , Wada, M. and Hirano, H.Y. (2003) The plant MITE mPing is mobilized in anther culture. Nature, 421, 167–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohany, O. , Gentles, A.J. , Hankus, L. and Jurka, J. (2006) Annotation, submission and screening of repetitive elements in Repbase: RepbaseSubmitter and Censor. BMC Bioinformatics, 7, 474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langmead, B. and Salzberg, S.L. (2012) Fast gapped‐read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods, 9, 357–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, X. , Guo, K. , Zhu, X. , Chen, P. , Li, Y. , Xie, G. , Wang, L. , Wang, Y. , Persson, S. and Peng, L. (2017) Domestication of rice has reduced the occurrence of transposable elements within gene coding regions. BMC Genom. 18, 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Librado, P. and Rozas, J. (2009) DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics, 25, 1451–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, X. , Long, L. , Shan, X. , Zhang, S. , Shen, S. and Liu, B. (2006) In planta mobilization of mPing and its putative autonomous element Pong in rice by hydrostatic pressurization. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 2313–2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C. , Chen, J. , Zhang, Y. , Hu, Q. , Su, W. and Kuang, H. (2012) Miniature inverted‐repeat transposable elements (MITEs) have been accumulated through amplification bursts and play important roles in gene expression and species diversity in Oryza sativa . Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1005–1017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X. , Fu, Y. , Zhao, X. , Jiang, L. , Zhu, Z. , Gu, P. , Xu, W. , Su, Z. , Sun, C. and Tan, L. (2016) Genomic structure analysis of a set of Oryza nivara introgression lines and identification of yield associated QTLs using whole genome resequencing. Sci. Rep. 6, 27425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M. (2011) Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high‐throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet J. 17, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- McClintock, B. (1984) The significance of responses of the genome to challenge. Science, 226, 792–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S. , Jung, K.H. , Lee, D.E. , Jiang, W.Z. , Koh, H.J. , Heu, M.H. , Lee, D.S. , Suh, H.S. and An, G. (2006) Identification of active transposon dTok, a member of the hAT family, in rice. Plant Cell Physiol. 47, 1473–1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito, K. , Cho, E. , Yang, G. , Campbell, M.A. , Yano, K. , Okumoto, Y. , Tanisaka, T. and Wessler, S.R. (2006) Dramatic amplification of a rice transposable element during recent domestication. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 17620–17625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naito, K. , Zhang, F. , Tsukiyama, T. , Saito, H. , Hancock, C.N. , Richardson, A.O. , Okumoto, Y. , Tanisaka, T. and Wessler, S.R. (2009) Unexpected consequences of a sudden and massive transposon amplification on rice gene expression. Nature, 461, 1130–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazaki, T. , Okumoto, Y. , Horibata, A. , Yamahira, S. , Teraishi, M. , Nishida, H. , Inoue, H. and Tanisaka, T. (2003) Mobilization of a transposon in the rice genome. Nature, 421, 170–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgel, L.E. and Crick, F.H.C. (1980) Selfish DNA: the ultimate parasite. Nature, 284, 604–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebollo, R. , Romanish, M.T. and Mager, D.L. (2012) Transposable elements: an abundant and natural source of regulatory sequences for host genes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 46, 21–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shan, X. , Liu, Z. , Dong, Z. , Wang, Y. , Chen, Y. , Lin, X. , Long, L. , Han, F. , Dong, Y. and Liu, B. (2005) Mobilization of the active MITE transposons mPing and Pong in rice by introgression from wild rice (Zizania latifolia Griseb.). Mol. Biol. Evol. 22, 976–990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J. , Liu, J. , Xie, K. , Xing, F. , Xiong, F. , Xiao, J. , Li, X. and Xiong, L. (2017) Translational repression by a miniature inverted‐repeat transposable element in the 3′ untranslated region. Nat. Commun. 8, 14651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit, A.F. (1996) The origin of interspersed repeats in the human genome. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 6, 743–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit, A.F. and Riggs, A.D. (1996) Tiggers and DNA transposon fossils in the human genome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 93, 1443–1448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song, X. and Cao, X. (2017) Transposon‐mediated epigenetic regulation contributes to phenotypic diversity and environmental adaptation in rice. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 36, 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studer, A. , Zhao, Q. , Ross‐Ibarra, J. and Doebley, J. (2011) Identification of a functional transposon insertion in the maize domestication gene tb1 . Nat. Genet. 43, 1160–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura, K. , Stecher, G. , Peterson, D. , Filipski, A. and Kumar, S. (2013) MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, L. , Zhang, P. , Liu, F. , Wang, G. , Ye, S. , Zhu, Z. , Fu, Y. , Cai, H. and Sun, C. (2008) Quantitative trait loci underlying domestication‐ and yield‐related traits in an Oryza sativa × Oryza rufipogon advanced backcross population. Genome, 51, 692–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukiyama, T. , Teramoto, S. , Yasuda, K. et al (2013) Loss‐of‐function of a ubiquitin‐related modifier promotes the mobilization of the active MITE mPing . Mol. Plant, 6, 790–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Z. (1997) Three novel families of miniature inverted‐repeat transposable elements are associated with genes of the yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti . Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 94, 7475–7480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X. , Weigel, D. and Smith, L.M. (2013) Transposon variants and their effects on gene expression in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker, T. , Guyot, R. , Yahiaoui, N. and Keller, B. (2003) CACTA transposons in Triticeae. A diverse family of high‐copy repetitive elements. Plant Physiol. 132, 52–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams‐Carrier, R. , Stiffler, N. , Belcher, S. , Kroeger, T. , Stern, D.B. , Monde, R.A. , Coalter, R. and Barkan, A. (2010) Use of Illumina sequencing to identify transposon insertions underlying mutant phenotypes in high‐copy Mutator lines of maize. Plant J. 63, 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witherspoon, D.J. , Zhang, Y. , Xing, J. , Watkins, W.S. , Ha, H. , Batzer, M.A. and Jorde, L.B. (2013) Mobile element scanning (ME‐Scan) identifies thousands of novel Alu insertions in diverse human populations. Genome Res. 23, 1170–1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, H. , Jiang, N. , Schaffner, E. , Stockinger, E.J. and van der Knaap, E. (2008) A retrotransposon‐mediated gene duplication underlies morphological variation of tomato fruit. Science, 319, 1527–1530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z. , Yan, X. , Maurais, S. , Fu, H. , O'Brien, D.G. , Mottinger, J. and Dooner, H.K. (2004) Jittery, a Mutator distant relative with a paradoxical mobile behavior: excision without reinsertion. Plant Cell, 16, 1105–1114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G. and Hall, T.C. (2003a) MAK, a computational tool kit for automated MITE analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3659–3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G. and Hall, T.C. (2003b) MDM‐1 and MDM‐2: two Mutator‐derived MITE families in Rice. J. Mol. Evol. 56, 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G. , Nagel, D.H. , Feschotte, C. , Hancock, C.N. and Wessler, S.R. (2009) Tuned for transposition: molecular determinants underlying the hyperactivity of a Stowaway MITE. Science, 325, 1391–1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Q. , Li, Z. , Li, W. et al (2013) CACTA‐like transposable element in ZmCCT attenuated photoperiod sensitivity and accelerated the postdomestication spread of maize. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 110, 16969–16974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye, K. , Schulz, M.H. , Long, Q. , Apweiler, R. and Ning, Z. (2009) Pindel: a pattern growth approach to detect break points of large deletions and medium sized insertions from paired‐end short reads. Bioinformatics, 25, 2865–2871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeadon, P.J. and Catcheside, D.E. (1995) Guest: a 98 bp inverted repeat transposable element in Neurospora crassa . Mol. Gen. Genet. 247, 105–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, Y.W. and Wessler, S.R. (2011) The catalytic domain of all eukaryotic cut‐and‐paste transposase superfamilies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 108, 7884–7889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou, J. , Zhang, S. , Zhang, W. , Li, G. , Chen, Z. , Zhai, W. , Zhao, X. , Pan, X. , Xie, Q. and Zhu, L. (2006) The rice HIGH‐TILLERING DWARF1 encoding an ortholog of Arabidopsis MAX3 is required for negative regulation of the outgrowth of axillary buds. Plant J. 48, 687–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Phenotypes of wild‐type (WT) and htd mutant rice.

Figure S2. Open reading frame (ORF) of HTD1 and deduced amino acid sequences in WT and htd.

Figure S3. Transposition of mJing in a high‐tillering dwarf population.

Figure S4. Changes in amino acid sequence encoded by the htd1 alleles and phenotypes of F4 individuals that have the mJing +/mJing − or mJing −/mJing − genotype.

Figure S5. Consensus sequences of target site duplications (TSDs) and terminal inverted repeats (TIRs) of 79 mJing‐like elements in the indica variety 93‐11 genome.

Figure S6. PCR analysis to detect co‐transformed transgenic plants.

Figure S7. Validation of the mJing insertion identified through targeted high‐throughput sequencing using PCR analysis.

Figure S8. Distribution and insertion preference of 297 mJing‐like elements identified through targeted high‐throughput sequencing.

Figure S9. Flow chart of the method used for targeted high‐throughput sequencing.

Table S1. Analysis of mJing excisions within the htd1 mutant allele in the F3 through F6 generations.

Table S2. Detailed information on 72 mJing‐like elements in the japonica rice variety Nipponbare genome (Os‐Nipponbare‐Reference‐IRGSP‐1.0, MSU7).

Table S3. Characteristics of target site duplications (TSDs) of 72 mJing‐like elements in the japonica variety Nipponbare genome (Os‐Nipponbare‐Reference‐IRGSP‐1.0, MSU7).

Table S4. Detailed information on 79 mJing‐like elements in the indica rice variety 93‐11 genome (ASM465v1).

Table S5. Presence/absence polymorphism of 297 mJing elements in the 71 samples surveyed.

Table S6. Characteristics of target site duplications (TSDs) of 297 mJing elements identified through targeted high‐throughput sequencing.

Table S7. Detailed information on 297 mJing elements identified through targeted high‐throughput sequencing.

Table S8. Information on mJing de novo insertions sites found in nine F5 individuals in which the mJing element was excised at the htd1 locus.

Table S9. Information of mJing de novo insertions found in the wild rice introgression lines.

Table S10. Oligonucleotides used in targeted high‐throughput sequencing.

Table S11. Enriched reads at the mJing insertions identified in japonica rice variety Do Khao (Chr12:25 499 426) and O. rufipogon accession IRGC89140 (Chr1:14 969 394).

Table S12. Primers used in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The GenBank accessions for nucleotide sequences of mJing and Jing identified in this study are MH727588 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MH727588) and MH727589 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MH727589), respectively. Clean data generated in targeted high‐throughput sequencing in this study have been deposited in NCBI's Short Read Archive under the accession PRJNA507518 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA507518).