Abstract

Background

The yield of whole‐body MRI for preventive health screening is currently not completely clear.

Purpose

To systematically review the prevalence of whole‐body MRI findings in asymptomatic subjects.

Study Type

Systematic review and meta‐analysis.

Subjects

MEDLINE and Embase were searched for original studies reporting whole‐body MRI findings in asymptomatic adults without known disease, syndrome, or genetic mutation. Twelve studies, comprising 5373 asymptomatic subjects, were included.

Field Strength/Sequence

1.5T or 3.0T, whole‐body MRI.

Assessment

The whole‐body MRI literature findings were extracted and reviewed by two radiologists in consensus for designation as either critical or indeterminate incidental finding.

Statistical Tests

Data were pooled using a random effects model on the assumption that most subjects had ≤1 critical or indeterminate incidental finding. Heterogeneity was assessed by the I 2 statistic.

Results

Pooled prevalences of critical and indeterminate incidental findings together and separately were 32.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 18.3%, 50.1%), 13.4% (95% CI: 9.0%, 19.5%), and 13.9% (95% CI: 5.4%, 31.3%), respectively. There was substantial between‐study heterogeneity (I 2 = 95.6–99.1). Pooled prevalence of critical and indeterminate incidental findings together was significantly higher in studies that included (cardio)vascular and/or colon MRI compared with studies that did not (49.7% [95% CI, 26.7%, 72.9%] vs. 23.0% [95% CI, 5.5%, 60.3%], P < 0.001). Pooled proportion of reported verified critical and indeterminate incidental findings was 12.6% (95% CI: 3.2%, 38.8%). Six studies reported false‐positive findings, yielding a pooled proportion of 16.0% (95% CI: 1.9%, 65.8%). None of the included studies reported long‐term (>5‐year) verification of negative findings. Only one study reported false‐negative findings, with a proportion of 2.0%.

Data Conclusion

Prevalence of critical and indeterminate incidental whole‐body MRI findings in asymptomatic subjects is overall substantial and with variability dependent to some degree on the protocol. Verification data are lacking. The proportion of false‐positive findings appears to be substantial.

Level of Evidence: 4

Technical Efficacy: Stage 3

J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2019;50:1489–1503.

Keywords: whole‐body MRI, health check‐up, screening, asymptomatic

THE AIM OF PREVENTIVE MEDICINE is to prevent the occurrence or halting of disease and averting resulting complications.1 With a general increase in health awareness and a desire to live longer and healthier,2, 3, 4 a greater utilization of preventive medicine measures can be expected. The lack of ionizing radiation makes magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) attractive for whole‐body screening, aiming at the detection of disease before its symptomatic manifestation.5 Early detection of malignant diseases (such as brain malignancies, lung carcinoma, hepatic malignancies, renal cancer, colonic cancer, lymphoma, and bone and soft‐tissue tumors) or cardiovascular diseases (such as aneurysms) may have a positive impact on the prognosis. In countries such as Canada, Germany, Japan, and the UK, whole‐body MRI is offered by private companies for health check‐up. However, in the Netherlands it is forbidden by law to date, because of uncertainty about the benefit and harms. Some asymptomatic subjects may benefit from timely intervention or treatment of early detected critical findings. However, discovery of indeterminate incidental findings (ie, findings for which the effectiveness of intervention or treatment is unknown) and false‐positive findings (ie, findings which eventually prove to be benign) can lead to unnecessary additional examinations, intervention, and treatment, with the associated risk of complications and costs. Moreover, knowledge of the existence of a critical finding for which no preventive or positive action can be taken, or informing a patient about the presence of an indeterminate incidental finding, can negatively affect psychological quality of life.6 In addition, a false‐negative finding may lead to false reassurance.7 To our knowledge, the first studies on whole‐body MRI for preventive screening were published in 2005.5, 8 In order to get an up‐to‐date insight into the yield of whole‐body MRI for preventive health screening, it was our objective to systematically review the prevalence of whole‐body MRI findings in asymptomatic subjects.

Materials and Methods

Data Sources

A computer‐aided search of the MEDLINE and Embase databases was conducted to find original articles reporting whole‐body MRI findings in symptomatic adult subjects without known disease, syndrome, or genetic mutation. The following search terms were used: (whole‐body OR WB OR full‐body) AND ((magnetic AND resonance) OR (MR AND imaging) OR MRI)) AND ((asymptomatic OR healthy OR symptom‐free OR volunteers OR controls OR population‐based OR (general AND population) OR screening OR (health AND check)). No beginning date limit was used. The search was updated until December 14, 2018. To expand our search, bibliographies of studies that finally remained after the selection process were screened for potentially suitable references.

Study Selection

Original studies reporting whole‐body MRI findings in asymptomatic adult subjects without known disease, syndrome, or genetic mutation were eligible for inclusion. There was no language restriction. Only studies that included at least the head, neck, chest, and abdomen (ie, cranial vertex to groin) in the field‐of‐view (FOV) were included. Studies that only imaged or analyzed selected body parts (such as the cardiovascular or musculoskeletal system) and studies that only analyzed selected, predefined findings (such as white matter lesions or liver steatosis) were excluded. Case reports were also excluded. When data were presented in more than one article, the article with the largest number of patients was chosen. With use of the aforementioned inclusion and exclusion criteria, titles and abstracts of the retrieved studies were reviewed. Articles were rejected if they were clearly ineligible. The full‐text version of each study that was potentially eligible for inclusion was retrieved. Full‐text articles were then reviewed to definitively determine if the study was eligible for inclusion.

Study Data Extraction

Data were extracted by one radiologist with 12 years of experience in data extraction for systematic reviews (R.M.K.). Data on study characteristics that might affect risk of bias were also extracted (Table 1). All whole‐body MRI findings, except predefined presumed benign findings (Table 2), were extracted. Descriptions of all extracted whole‐body MRI findings were reviewed in consensus by two radiologists (R.M.K. and T.C.K., each with 12 years of clinical experience) for designation as either critical finding or indeterminate incidental finding. Critical findings were defined as findings that could result in mortality or considerable morbidity if they were not appropriately treated.9 Indeterminate incidental findings were defined as findings for which the effectiveness of intervention or treatment was unknown.10 The number of critical and indeterminate incidental findings verified by additional examinations, resection, or follow‐up were extracted. Furthermore, all reported true positives (ie, critical or indeterminate incidental findings confirmed by additional examinations, resection, or follow‐up), false positives (ie, critical or indeterminate incidental findings eventually found to be a benign finding), and false‐negative findings (ie, discovery of critical or indeterminate incidental findings on additional examinations, after resection, or follow‐up) were extracted.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics That Might Affect Risk of Bias

| Study | Prospective or retrospective design | Subject selection | Identical whole‐body MRI protocol used in all subjects | Whole‐body MRI interpreter(s) (number, subspecialty, experience) and method of reading |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al14 | Retrospective | Consecutive | Yes | A fellowship‐trained musculoskeletal radiologist, neuroradiologist, and abdominal radiologist with 14, 20, and 15 years' experience). Independent reading, discrepancies were resolved in consensus. |

| Perkins et al15 | Not specified | Not specified | Yes | Not reported |

| Saya et al16 | Not specified | Not specified | Yes |

Two radiologists with at least 5 years’ experience. Independent reading, discrepancies were resolved in consensus with a third radiologist. |

| Ulus et al17 | Prospective | Consecutive | Yes | Two radiologists with ≈15 years' experience in MRI. Independent reading, discrepancies were resolved in consensus. |

| Tarnoki et al19 | Retrospective | Not specified | Yes |

A resident in radiology (2–4 years’ experience) and two senior radiologists. Independent reading, discrepancies were resolved in consensus. |

| Cieszanowski et al20 | Retrospective | Not specified | Yes | Two radiologists with 10 and 10–years, experience in MRI interpretation. Independent reading, discrepancies were resolved in consensus. |

| Hegenscheid et al21 | Prospective | Consecutive | Noa | Two radiology residents with 1–5 years’ experience in MRI interpretation. Independent reading, discrepancies were resolved in consensus with a senior radiologist with 15 years' experience. |

| Laible et al11 | Prospective | Consecutive | Nob | Two radiologists with more than 6 years' experience in cardiovascular MRI. Independent reading, discrepancies were resolved in consensus. |

| Takahara et al23 | Prospective | Consecutive | Yes | Two radiologists with 12 and 20 years’ experience in MRI interpretation. Independent reading. |

| Lo et al26 | Prospective | Not specified | Yes | Five radiologists, each with more than 10 years’ experience in MRI interpretation. Method of reading not reported |

| Baumgart et al12 | Not specified | Consecutive | Yes | Interpreter(s) and method of reading not reported |

| Goehde et al5 | Not specified | Not specified | Yes | Two radiologists with >5 years' experience in MRI. Consensus reading. |

Male subjects had the option of undergoing contrast‐enhanced cardiac MRI and MR angiography, and female subjects had the option of undergoing cardiac MRI and contrast‐enhanced MR mammography.

The first 36 subjects were imaged using a standard clinical 1.5T MRI scanner equipped with eight receiver channels. The following 102 subjects were imaged using a 1.5T MRI scanner equipped with 32 receiver channels.

Table 2.

Predefined Presumed Benign Findings per Body Part

| Body part | Predefined presumed benign finding |

|---|---|

|

Head |

Benign intracranial cysts (arachnoid cysts, pineal gland cysts, choroid plexus cysts, pituitary cysts), dilated Virchow‐Robin spaces |

| Neck | Sinus mucosal thickening or retention cysts, nasopharyngeal cysts, simple thyroid cysts |

| Chest and breast | Lung or pleural scars, bronchogenic cysts, pericardiac cysts, breast cysts |

| Abdomen | Benign liver lesions (cysts, hemangiomas, focal nodular hyperplasia), cholecystolithiasis, splenic hemangioma or cyst, uncomplicated renal cysts, renal angiomyolipoma ≤2 cm,31 adrenal adenoma, prostatic hyperplasia, uterine myoma, uterine adenomyosis, benign‐appearing ovarian cysts, colonic diverticuli, hydrocele |

| Musculoskeletal | Degenerative spinal disease, scoliosis, spondylolisthesis, perineural cysts, sacral meningocele, osteoarthritic joint changes, subacromial bursitis, Baker's cysts, benign‐appearing bone or soft tissue lesions |

| Other | Benign anatomic variants (azygos lobe, unilateral renal agenesis, vascular anatomic variants) |

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta‐Analysis, v. 3.0 (Biostat, Englewood, NJ). Data were pooled using a random effects model. The majority of the included studies only reported the total number of critical or indeterminate incidental findings, without mentioning the number of subjects in whom these findings were observed. Prevalence was pooled on the assumption that most included subjects had no more than one critical or indeterminate incidental finding. In three studies,5, 11, 12 reported cardiac abnormalities (such as infarction and myocardial dysfunction) (Table 3) may overlap in one subject. Therefore, only the cardiac abnormality with the highest prevalence was used for the pooled analysis.

Table 3.

Critical and Indeterminate Incidental Findings, Validated Findings, and Reported True‐Positive, False‐Positive, and False‐Negative Findings per Included Study

| Study | Critical findings (number) | Indeterminate incidental findings (number) | Frequency of reported validated findings | Reported true‐positive findings (number) and final diagnosis | Reported false‐positive findings (number) and final diagnosis | Reported false negatives (number) and final diagnosis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al14 |

‐ Tongue mass (1) ‐ Renal mass (4) ‐ Pancreas lesion (1) ‐ Aortic dissection (1) ‐ Hepatic nodule or mass (13) ‐ Hydronephrosis (1) ‐ Complex ovary cyst (6) ‐ Dilatation of biliary tree (2) ‐ Pancreatic duct dilatation (4) ‐ Enlarged cervical lymph nodes (short axis >1 cm) (2) |

‐ Cerebromalacia (1) ‐ Thyroid nodule (4) ‐ Diffuse thyroid abnormality (2) ‐ Gallbladder polyps (3) ‐ Cystic pancreatic lesion (2) ‐ Neurogenic tumor (1) ‐ Vertebral compression fracture (4) ‐ Bone marrow edema (14) |

1/66 | Renal mass (1) → carcinoma | NR | NR |

| Perkins et al15 |

‐ Intracranial aneurysm (1) ‐ Anterior mediastinal mass (1) ‐ Enlarged aortic root (1) ‐ Lung lesion (1) ‐ Possible renal mass (1) ‐ Complex renal mass (1) ‐ Complicated renal cyst (1) ‐ Prostate lesion (2) ‐ Common iliac artery aneurysm of 2.6 cm (1) |

‐ String of beads appearance of cervical carotid arteries (may represent fibromuscular dysplasia) (1) ‐ 50% loss of signal of the left internal carotid artery at the junction of the cavernous and petrous portions (1) ‐ Cystic parotid gland lesion (1) |

8/13 |

‐ Anterior mediastinal mass (1) → thymoma ‐ Possible renal mass (1) → carcinoma ‐ Prostate lesion (2) → carcinoma ‐ Cystic parotid gland lesion (1) → pleiomorphic adenoma |

‐ String of beads appearance of cervical carotid arteries (1) → refuted (no abnormality) ‐ Complicated renal cyst (1) → Bosniak 2 cyst ‐ Complex renal mass (1) → refuted (no abnormality) |

NR |

| Saya et al 16 | None | ‐Edema and fatty changes in the gastrocnemius muscle (1) | 1/1 | None | Edema and fatty changes in the gastrocnemius muscle (1) → benign vascular malformation | NR |

| Ulus et al17 |

‐ Pulmonary nodule (1) ‐ Tuberculosis pneumonia (1) ‐ Renal mass (1) ‐ Adrenal mass (1) ‐ Cystic pancreatic mass (1) ‐ Splenic mass (1) |

‐ Thyroid nodule (8) ‐ Spinal epidural mass (2) |

15/16 |

‐ Renal mass (1) → carcinoma ‐ Adrenal mass (1) → carcinoma ‐ Spinal intradural mass (2) → schwannoma ‐ Cystic pancreatic mass (1) → mucinous cystadenocarcinoma |

‐ Thyroid nodules (8) → benign nodules ‐ Pulmonary nodule (1) <5 mm → benign ‐ Splenic mass (1) → healing hydatic cyst lesion |

‐ Thyroid carcinoma (1) diagnosed after one year ‐ Coccygeal chordoma (1) diagnosed after two years |

| Tarnoki et al19 |

‐ Lung lesion (1) ‐ Pararectal lesion suspected for malignancy (1) ‐ Solid liver lesion (3) ‐ Pleural effusion (3) ‐ Ascites (1) |

‐ Nonspecific lymph nodes (5) ‐ Liver steatosis (1) ‐ Inguinal hernia (1) |

0/16 | NR | NR | NR |

| Cieszanowski et al20 |

‐ FLAIR hyperintense area in frontal lobe (1) ‐ Pulmonary nodule (59) ‐ Lung lesion (1) ‐ Renal lesion (1) ‐ Complicated renal cyst (1) ‐ Ovarian tumor (1) ‐ Testicular lesion (1) ‐ Lung, liver and adrenal gland lesions (1) ‐ Enlarged neck lymph nodes (21) ‐ Enlarged thoracic lymph nodes (32) ‐ Enlarged abdominal lymph nodes (10) ‐ Splenomegaly (10) |

‐ Brain infarctions (169) ‐ Cerebral atrophy (8) ‐ Thyroid nodules/cysts (81) ‐ Hepatic steatosis (126) ‐ Cystic pancreatic lesion (12) ‐ Bone marrow edema (32) ‐ Endplate fracture (17) |

5/584 |

‐ FLAIR hyperintense area in frontal lobe (1) → glioma ‐ Lung lesion (1) → carcinoma ‐ Renal lesion (1) → renal carcinoma ‐ Testicular lesion (1) → Leydig cell tumor ‐ Lung, liver and adrenal lesions (1) → metastases |

NR | NR |

| Hegenscheid et al21 |

‐ Brain glioma (2) ‐ Brain metastasis (1) ‐ Intraventricular tumor (8) ‐ Subdural hematoma (1) ‐ Intracranial aneurysm (15) ‐ Normal pressure hydrocephalus (1) ‐ Extracranial soft tissue tumor (1) ‐ Goitre with tracheal compression (9) ‐ Thyroid tumor (3) ‐ Cystic or solid pharyngeal or laryngeal tumor (40) ‐ Cystic or solid salivary gland tumor (9) ‐ Cervical lymphadenopathy (8) ‐ Pulmonary nodule (56) ‐ Pneumonia (5) ‐ Pleural effusion (2) ‐ Hilar, mediastinal or axillary lymphadenopathy (13) ‐ Thoracic aorta aneurysm (10) ‐ Heart failure (5) ‐ Myocardial tumor (1) ‐ Pericardial effusion (1/) ‐ Breast lesion ≥BI‐RADS 3 (97) ‐ Hepatocellular carcinoma (1) ‐ Unclear liver lesion (44) ‐ Liver cirrosis (8) ‐ Liver hemochromatosis (5) ‐ Cholestasis (24) ‐ Pancreatic tumor (11) ‐ Splenomegaly (7) ‐ Splenic tumor (5) ‐ Gastrointestinal tumor (6) ‐ Complex renal cyst (110) ‐ Renal carcinoma (13) ‐ Unclear adrenal tumor (8) ‐ Chronic urinary obstruction (5) ‐ Urinary bladder tumor (6) ‐ Complex ovarian cyst or tumor (80) ‐ Uterine or cervical tumor (13) ‐ Abdominal lymphadenopathy (16) ‐ Testicular, epididymal or seminal vesicle tumor (7) ‐ Inguinal testis (11) ‐ Abdominal aorta aneurysm (10) ‐ Absolute spinal canal stenosis with myelopathy (49) ‐ Intraspinal tumor (7) ‐ Bone metastases (8) ‐ Plasmacytoma (2) |

‐ Brain infarction (1) ‐ Brain cavernoma (13) ‐ Pituitary adenoma (9) ‐ Meningioma (9) ‐ Vestibular schwannoma (1) ‐ >50% internal carotid artery stenosis (15) ‐ Thoracic aorta stenosis (1) ‐ Angiomyolipoma (9) ‐ Large abdominal herniation (3) ‐ Abdominal aorta stenosis (3) ‐ Severe bone edema (23) |

0/833 | NR | NR | NR |

| Laible et al11 |

‐ Signs of pericarditis (1) ‐ Pneumonia (1) ‐ Low‐grade aortic aneurysm (2) ‐ Unspecified brain lesion (10) ‐ Pulmonary nodule (1) ‐ Enlarged mediastinal, hilar, or axillary lymph nodes (5) ‐ Encapsulated pleural effusion (1) ‐ Aortic wall ulcer (1) ‐ Cirrhosis, liver steatosis, or ascites (2) ‐ Compression of celiac trunk (2) ‐ Infrarenal aortic dissection (1) ‐ Superficial femoral artery dissection (1) |

‐ Gliosis (6) ‐ White‐matter lesions (9) ‐ Meningioma (1) ‐ Microangiopahic brain changes (3) ‐ Atypical intracranial vessels (1) ‐ Cardiac abnormalities (myocardial hypertrophy (4), infarction (2/), cardiac perfusion deficit (13), myocardial wall motion abnormalities (6), global myocardial dysfunction with ejection fraction <50% (5), valve diseases (9) ‐ Atherosclerosis of large extracranial arteries causing ≥50–70% stenosis (18) |

0/79 | NR | NR | NR |

| Takahara et al23 | ‐Lung lesion (1) | NR | 1/1 | Lung lesion (1) → carcinoma | NR | NR |

| Lo et al26 |

‐ Lung lesion (4/) ‐ Mediastinal lesion (1) ‐ Liver nodules (2) ‐ Renal mass (2) ‐ Pancreatic lesion (1) ‐ Retroperitoneal mass (1) ‐ Prostatic lesion (1) ‐ Bone lesion (2) ‐ Liver cirrhosis (1) ‐ Liver hemochromatosis (1) |

‐ Thyroid nodules (10) ‐ Borderline‐sized lymph nodes (3) |

24/29 |

‐ Thyroid nodule (1) → Hurthle cell tumor ‐ Lung lesion (1) → carcinoma ‐ Renal mass (1) → carcinoma |

‐ Thyroid nodules (9) → benign ‐ Lung lesions (3) → benign ‐ Mediastinal lesion (1) → benign ‐ Liver nodules (2) → benign ‐ Renal mass (1) → angiomyolipoma ‐ Retroperitoneal mass (1) → benign neuroendocrine tumor ‐ Pancreatic lesion (1) → refuted (no abnormality) ‐ Prostatic lesion (1) → refuted (no abnormality) ‐ Bone lesion (2) → benign |

NR |

| Baumgart et al12 |

‐ Intracranial aneurysm (2) ‐ Bronchial carcinoma (2/) ‐ Colon polyps (75) ‐ Renal lesion (5) ‐ Aortic aneurysm (27, 2 >5 cm in size) |

‐ Microangiopathic brain changes (191) ‐ Extra‐axial brain tumor (11) ‐ Cardiac abnormalities (left ventricular hypertrophy (236), infarction (29)) ‐ 10–60% (141) and 60–99% (4) carotid stenosis ‐ Pelvic and leg artery stenosis (49) |

80/743 |

‐ Colon polyps (73) → confirmed ‐ Renal lesion (5) → renal carcinoma |

Colon polyps (2) → refuted (no abnormality) |

NR |

| Goehde et al5 |

‐ Small cerebral tumor (1) ‐ Intracranial aneurysm (1) ‐ Thoracic aorta aneurysm (>4 cm (1/298) ‐ Pulmonary nodule (2, each subject two pulmonary nodules) ‐ Colon polyps (12) ‐ Renal mass (1) ‐ Complicated renal cyst (2) ‐ Infrarenal aortic aneurysm (>4 cm) (2) ‐ Vertebral lesion (1) |

‐ Brain infarction (2) ‐ Cerebral atrophy (1) ‐ Microangiopathic brain changes (5) ‐ Thalamic cavernoma (1) ‐ Intracranial internal carotid artery stenosis (1) ‐ Thyroid lesions/enlargement (4) ‐ Cardiac abnormalities (infarction (1), global or regional myocardial dysfunction (5)) ‐ Hepatic adenoma (1) ‐ Gastric herniation (1) ‐ Atherosclerosis of large extracranial arteries (7) (causing >50% carotid stenosis (2), renal artery stenosis (1), iliac artery stenosis (1), and lower limb artery stenoses (3)) ‐ Focal dissection of infrarenal aorta (1) ‐ Focal dissection of superficial femoral artery (1) |

35/53 |

‐ Intracranial aneurysm (1) → confirmed ‐ Cerebral atrophy (1) → confirmed ‐ Thalamic cavernoma (1) → confirmed ‐ Global or regional myocardial dysfunction (5) → confirmed ‐ Hepatic adenoma (1) → confirmed ‐ Renal mass (1) → carcinoma ‐ Colon polyps (12) → confirmed ‐ Infrarenal aortic aneurysm (2) → confirmed ‐ Arterial stenoses (6) → confirmed ‐ Focal dissection of infrarenal aorta (1) → confirmed ‐ Focal dissection of superficial femoral artery (1) → confirmed |

‐ Pulmonary nodules (2, each subject two pulmonary nodules) → benign ‐ Vertebral lesion (1) → hemangioma |

NR |

aIn Ulus et al's study,17 hepatomegaly, hepatosteatosis, gallbladder polyps smaller than 5 mm, and bladder stones were also detected by whole‐body MRI, but the numbers were not reported. Therefore, we did not include these findings in this table.

The proportion of critical and indeterminate incidental findings verified by additional examinations, resection, or follow‐up was pooled. Proportions of reported false positive (ie, number of reported false‐positive findings divided by number of all critical and indeterminate incidental findings) and false‐negative findings (ie, number of reported false‐negative findings divided by number of all subjects without critical or indeterminate incidental findings) were also pooled, if there were data from at least three studies. Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by calculating the I 2 statistic,13 which ranges from 0 (no heterogeneity) to 100% (all variance due to heterogeneity). Substantial heterogeneity was defined as I 2 > 50%. Potential sources for heterogeneity were explored by subgroup analyses. Covariates were publication year (published in or after vs. published before 2014 [2014 was the median]), study size (>174 vs. <174 subjects [174 was the median]), and additional use of (cardio)vascular or colon MRI. P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant result for all analyses.

Results

Literature Search

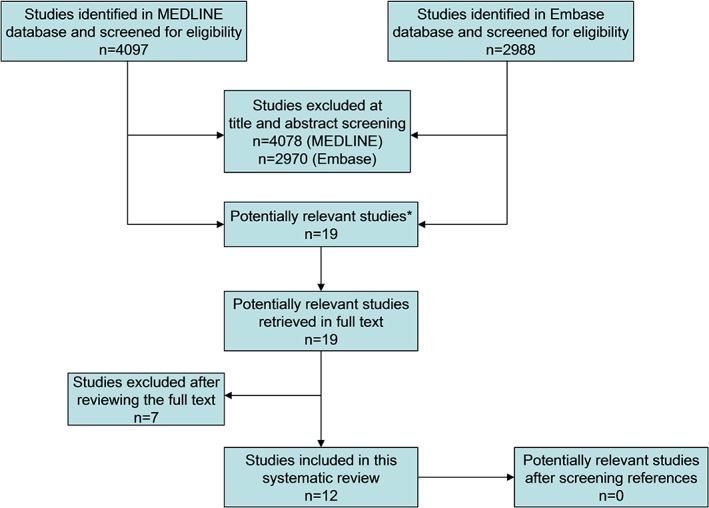

The study selection process is displayed in Fig. 1. Reviewing titles and abstracts of the MEDLINE and Embase databases resulted in 19 studies that were potentially eligible for inclusion.5, 8, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28 After reviewing the full text, five studies were excluded because data were also used in another article from the same group, comprising a larger number of patients8, 18, 25, 27, 28; one study was excluded because it only reported study rationale and design,22 and one study was excluded because it was not clear whether the head and neck region was included in the FOV.22 Eventually, 12 studies were included in this systematic review, published between 2005 and 2018.5, 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 20, 21, 23, 26 Screening the reference lists of these articles did not result in other potentially relevant studies. The principal characteristics of the included studies are presented in Table 4. A standard whole‐body MRI protocol typically included conventional T1‐weighted and fat‐suppressed T2‐weighted sequences, without the use of gadolinium chelate‐enhanced sequences. Some of the included studies obtained additional diffusion‐weighted images and some of the included studies performed additional (cardio)vascular or colon MRI.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection process. *One potentially relevant study was found in the MEDLINE database but not in the Embase database,11 the other 19 potentially relevant studies were found in both databases.

Table 4.

Principal Study Characteristics

|

Study, publication year, country of origin |

Description of subjects | Number of subjects, age and sex |

MRI field strength Sequences Total scan time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al, 14 2018, Korea | Asymptomatic subjects undergoing health check‐up | 229 subjects, mean age 52 years (range 37–73), 139 males |

1.5T Whole body: coronal T1w FS (3D SPGR), coronal T2w STIR, and sagittal T2w 20 minutes, 28 s |

| Perkins et al,15 2018, USA | Asymptomatic subjects undergoing health check‐up | 209 subjects, mean age 55 years (range 20–98), 137 males |

3T Whole‐body: noncontrast, not further specified NR |

| Saya et al,16 2017, UK | Asymptomatic controls with no cancer history and minimal familial cancer history | 44 subjects, median age 38 years (range 19–58), 17 males |

1.5T Whole body: axial T1w, axial T2w FS HASTE and DWIBS, and coronal T1 VIBE NR |

| Ulus et al,17 2016, Turkey | Asymptomatic subjects undergoing health check‐up | 118 subjects, mean age 47.4 years (range 20–81), 71 males |

1.5T ‐ Whole body: coronal T2w HASTE and STIR, and axial T2w ‐ Upper abdomen: axial T1w in‐ and out‐of‐phase and DWI For 12 subjects intravenous contrast was used for lesion characterization 30 minutes (range 28–35) |

| Tarnoki et al,19 2015, Germany | Asymptomatic subjects undergoing health check‐up | 22 subjects, mean age 47 years (±9), 18 males |

3T ‐ Whole body: coronal T1w and STIR, and axial DWIBS ‐ Large extracranial arteries: contrast‐enhanced MRA NR |

| Cieszanowski et al,20 2014, Poland | Asymptomatic subjects undergoing health check‐up | 666 subjects, mean age 46.4 years (age range 20–77), 465 males |

1.5T ‐ Whole body: coronal T2w STIR ‐ Whole spine: sagittal T2w STIR ‐ Neck and trunk: Axial T2w TSE FS ‐ Brain: axial FLAIR ‐ Thorax: axial and coronal 3D T1w GE FS ‐ Abdomen: axial T2w TSE, 3D T1w GE FS, and in‐ and out‐of‐phase 50 minutes |

| Hegenscheid et al,21 2013 Germany | Random sample of adults | 2500 subjects, mean age 53 years (range 21–88), 1229 males |

1.5T ‐ Whole body: coronal TIRM, and sagittal T1w, T2w, and T2w* ‐ Brain: sagittal T2, and axial T1w, FLAIR, DWI, SWI, and 3D TOF MRA ‐ Neck: axial T1w ‐ Chest: axial T1 VIBE and T2 HASTE ‐ Abdomen: axial T2w FS, T1w FLASH FS, DWI, and T1w VIBE, and coronal 3D T2w (MRCP) ‐ Pelvis: axial PDw FS ‐ Cardiac: true FISP short axis and 2‐ and 4 chamber views, cine short axis, axial and 2‐, 3‐ and 4‐chamber views, and late enhancement ‐ Large arteries (men only): pre and postcontrast T1 FLASH ‐ Breast (women only): axial TIRM, T2w, DWI, and dynamic axial 3D T1w FLASH NR |

|

Laible et al,11 2012, Germany |

Asymptomatic subjects undergoing health check‐up | 138 subjects, mean age 54 years (range 39–74), 118 males |

1.5T ‐ Brain: T1w, T2w, (and DWI) ‐ Thorax: half‐Fourier RARE and VIBE ‐ Abdomen: half‐Fourier RARE and FLASH ‐ Cardiac: true FISP, myocardial perfusion (saturation‐recovery true FISP), and late enhancement ‐ Large extracranial arteries: contrast‐enhanced MRA NR |

| Takahara et al,22 2010, Japan | Asymptomatic subjects undergoing health check‐up | 10 subjects, mean age 61.6 years (range 52–79), 5 males |

1.5T Whole body: coronal T1w and T2w, and axial DWI NR |

| Lo et al,26 2008, Hong Kong | Asymptomatic medical doctors | 132 subjects, mean age 56 years (range 38–82), 111 males |

3T ‐ Brain: axial T1w and T2w ‐ Neck: axial T2w FS ‐ Thorax: axial T1w FLASH and T2w HASTE ‐ Abdomen: axial T1w FLASH, T2w HASTE, and T1w FS ‐ Pelvis: axial T1w FLASH and T2w HASTE ‐ Spine: sagittal T2 STIR ‐ Whole body: coronal T1 FLASH 13 minutes, 31 s |

| Baumgart et al,12 2007, Germany | Asymptomatic subjects undergoing health check‐up | 1007 subjects, mean age 55 years (range 40–67), 720 males |

1.5T ‐ Brain: axial pre and postcontrast T1w, axial and sag T2w, and 3D TOF MRA ‐ Large extracranial arteries: 3D contrast‐enhanced MRA ‐ Heart: standard, cine and late enhancement short and long axis views, Lungs: axial VIBE ‐ Colon: T1w colonography ‐ Prostate: T2w 60 minutes |

| Goehde et al,5 2005, Germany | Asymptomatic subjects undergoing health check‐up | 298 subjects, mean age 49.7 years (range 31–73), 247 males |

1.5T ‐ Brain: axial T1w, T2w, FLAIR, DWI and 3D TOF MRA ‐ Large extracranial arteries: 3D coronal FLASH contrast‐enhanced MRA ‐ Thorax: axial HASTE ‐ Heart: CINE (true FISP) and late enhancement short axis and 2‐ and 4 chamber views ‐ Colon: axial pre and postcontrast T1 VIBE 50 minutes |

DWI: diffusion‐weighted imaging; DWIBS: diffusion‐weighted whole body imaging with background body signal suppression; FISP: fast imaging with steady state precession; FLAIR: fluid‐attenuated inversion recovery; FLASH: fast low‐angle shot; FS: fat suppression; HASTE: half‐Fourier acquired single turbo spin‐echo; MRA: magnetic resonance angiography; MRCP: magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; PD: proton density weighted; RARE: rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement; SPGR: spoiled gradient‐echo; SWI: susceptibility weighted imaging; T1w: T1‐weighted; T2w: T2‐weighted; TIRM: turbo inversion recovery magnitude; TOF: time‐of‐flight; VIBE: volumetric interpolated breath‐hold examination.

Study Quality

Data on study characteristics that might affect risk of bias are displayed in Table 1. The study design was prospective in five studies, retrospective in three studies, and in four studies it was not specified. In half of the included studies, subjects were enrolled consecutively; in the other half, it was not specified whether subjects were enrolled consecutively or randomly. In all but two studies, all subjects were scanned with an identical whole‐body MRI protocol. In the majority of included studies, whole‐body MRI scans were read independently by two or more interpreters and discrepancies were resolved in consensus.

Prevalence of Whole‐Body MRI Findings and Reported False Positives

The median number of subjects per included study was 174 (range 10–2500). The total sample size comprised of 5373 subjects. Pooled frequency of male subjects was 68.6% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 59.7%, 76.2%). A detailed description of critical and indeterminate incidental findings, verified findings, and reported true‐positive, false‐positive, and false‐negative findings per included study is displayed in Table 3.

Pooled prevalences of critical and indeterminate incidental findings together and separately were 32.1% (95% CI: 18.3%, 50.1%), 13.4% (95% CI: 9.0%, 19.5%), and 13.9% (95% CI: 5.4%, 31.3%), respectively. There was substantial between‐study heterogeneity (I 2 = 95.6–99.1). Pooled prevalence of critical and indeterminate incidental findings together was significantly higher in studies that included (cardio)vascular and/or colon MRI in the protocol compared with studies that did not (49.7% [95% CI, 26.7%, 72.9%] vs. 23.0% [95% CI, 5.5%, 60.3%], P < 0.001). Prevalence was not statistically significantly different in subgroups according to publication year and study size (Table 5).

Table 5.

Subgroup Analyses.

| Parameter | Variablesa | Pooled prevalence of all critical and indeterminate incidental findings | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publication year |

Published in or after (6) vs. published before 2014 (6) |

27.4 (6.1, 68.7) vs. 35.5 (17.9, 58.1) |

0.710 |

| Study size | >174 (6) vs. <174 subjects (6) |

38.8 (17.9, 64.7) vs. 25.3 (10.4, 49.7) |

0.418 |

| (Cardio)vascular and/or colon MRI in the protocol | Yes (5) vs. no (6)b |

49.7 (26.7, 72.9) vs. 23.0 (5.5, 60.3) |

<0.001 |

Data in parentheses are number of studies.

One study15 did not specify the whole‐body MRI and was therefore not included in this subgroup analysis.

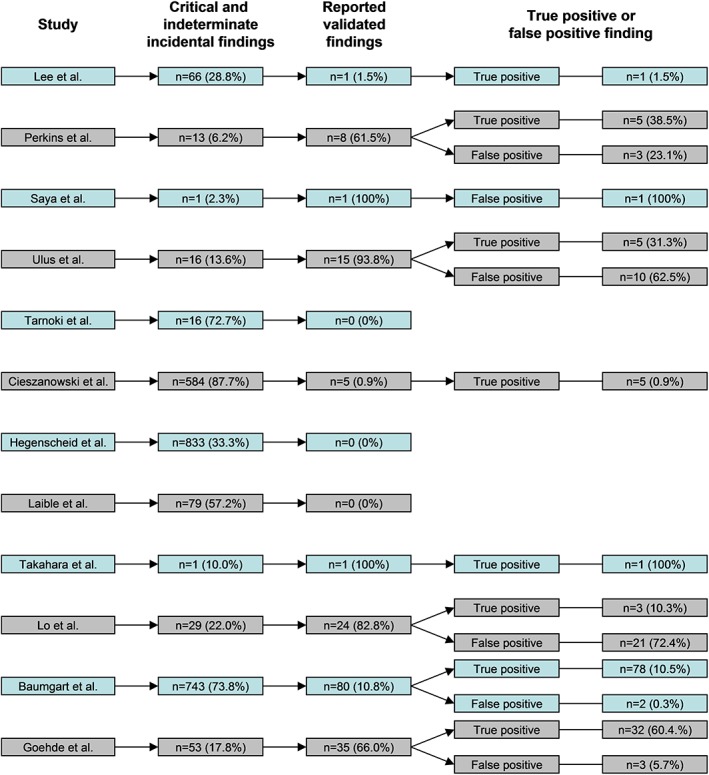

An overview of critical and indeterminate incidental findings, reported validated findings, and true‐positive and false‐positive findings per included study is given in Fig. 2. Pooled proportion of reported verified critical and indeterminate incidental findings was 12.6% (95% CI: 3.2%, 38.8%). False‐positives findings were reported by six studies,5, 12, 15, 16, 17, 26 with a pooled proportion of 16.0% (95% CI: 1.9%, 65.8%). None of the included studies reported long‐term (>5 year) verification of negative findings. Only one study17 performed 3–5‐year follow‐up for the majority (64%) of included subjects, by reviewing any performed radiological work‐up, medical records, and/or telephone interviews: reported proportion of false‐negative findings was 2.0%.18

Figure 2.

Overview of critical and indeterminate incidental findings, reported verified findings, and true‐positive and false‐positive findings per included study.

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta‐analysis demonstrated that the prevalence of critical and indeterminate incidental findings on whole‐body MRI in asymptomatic subjects is overall substantial. Studies including (cardio)vascular and/or colon MRI had significantly more critical and indeterminate incidental findings. This is due to the fact that these additional dedicated MRI protocols are more sensitive than general screening whole‐body MRI for the detection of (cardio)vascular diseases and colon neoplasms. A substantial proportion of critical and indeterminate incidental whole‐body MRI findings proved to be false positive. There was a large number of critical and indeterminate incidental findings without reported verification (Table 3, Fig. 2) and none of the included studies performed systematic and long‐term follow‐up to verify whole‐body MRI examinations with negative findings. Therefore, false‐positive and false‐negative findings may be underreported.

The use of different MRI protocols leads to different sensitivity and specificity, and this was probably the main cause of between‐study heterogeneity. For example, in one study a coccygeal chordoma was probably not detected because no sequence in the sagittal plane was acquired.17 In another study, lung carcinoma was only detected on diffusion‐weighted imaging.23 In yet another study,17 gadolinium‐enhanced sequences were used in 12 subjects for lesion characterization, which increases specificity (and decreases false‐positive findings). Because there was a large variation in MRI protocols used by the included studies, we could not explore the effect of relevant parameters (such as the use of different imaging planes and sequences) on the prevalence of whole‐body MRI findings. All except two studies reported that whole‐body MRI was interpreted by at least two observers, of which at least one was an experienced radiologist. Therefore, we believe that interpreter skill was not a major contributor to between‐study heterogeneity. Nevertheless, it should be noted that whole‐body MRI for preventive health screening is not widely available yet and radiologists in general may have little experience/skills in interpreting whole‐body MRI.

Our systematic review had several limitations. First, a major limitation of our study is that prevalence data were pooled on the assumption that most included subjects had no more than one critical or indeterminate incidental finding. Second, there is no (inter)national consensus list of critical and indeterminate incidental findings.29, 30 All extracted whole‐body MRI findings were reviewed by consensus of two radiologists based on the available information in the original studies. Potentially relevant information such as subject's age and gender, and exact location, size, and signal characteristics of detected lesions were not presented for each subject. This may have resulted in overestimation of prevalence. Third, as mentioned above, we could not fully explore potential sources of heterogeneity by subgroup analyses. Fourth, as there is no validated quality assessment tool for prevalence studies, study quality was not formally assessed. Fifth, the included studies investigated mainly adult male subjects. It could be possible that male subjects were more likely to participate because of a generally higher socioeconomic status. Because of incomplete reporting, we could not pool data for male and female subjects separately. Therefore, the results of our systematic review and meta‐analysis are only generalizable to an asymptomatic population consisting of mainly adult male subjects.

Many people attach high value to the incidental MRI findings of disease that "can save lives." However, there is a need for balance between the benefit and harm of whole‐body screening in asymptomatic subjects. Based on current evidence, healthcare providers should not offer whole‐body MRI for preventive health screening to asymptomatic subjects outside of a research setting. Asymptomatic subjects undergoing whole‐body MRI should be informed about the substantial prevalence of critical and indeterminate incidental findings, the lack of verification data, and the apparent substantial proportion of false‐positive findings.

In order to better understand the potential benefit and harms of whole‐body MRI for preventive health screening, an international consensus list of critical findings would be helpful for standardization and comparison of (future) study results. Furthermore, it remains to be investigated which whole‐body MRI protocol achieves the best sensitivity and specificity. Only a randomized trial with long‐term follow‐up can definitely answer the question of whether or not whole‐body MRI for preventive health screening is beneficial.

In conclusion, the prevalence of critical and indeterminate incidental whole‐body MRI findings in asymptomatic subjects is overall substantial, and with variability dependent to some degree on the protocol. Verification data are lacking. The proportion of false‐positive findings appears to be substantial.

References

- 1. Clarke EA. What is preventive medicine? Can Fam Phys 1974;20:65–68 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kumar S, Preetha G. Health promotion: An effective tool for global health. Indian J Commun Med 2012;37:5–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Musich S, Wang S, Hawkins K, Klemes A. The impact of personalized preventive care on health care quality, utilization, and expenditures. Popul Health Manag 2016;19:389–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Donner Y, Fortney K, Calimport SR, Pfleger K, Shah M, Betts‐LaCroix J. Great desire for extended life and health amongst the American public. Front Genet 2016;6:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Goehde SC, Hunold P, Vogt FM, et al. Full‐body cardiovascular and tumor MRI for early detection of disease: Feasibility and initial experience in 298 subjects. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2005;184:598–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Schmidt CO, Hegenscheid K, Erdmann P, et al. Psychosocial consequences and severity of disclosed incidental findings from whole‐body MRI in a general population study. Eur Radiol 2013;23:1343–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cooper GC, Harvie MN, French DP. Do negative screening test results cause false reassurance? A systematic review. Br J Health Psychol 2017;22:958–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kramer H, Schoenberg SO, Nikolaou K, et al. Cardiovascular screening with parallel imaging techniques and a whole‐body MR imager. Radiology 2005;236:300–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anthony SG, Prevedello LM, Damiano MM, et al. Impact of a 4‐year quality improvement initiative to improve communication of critical imaging test results. Radiology 2011;259:802–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eisenberg RL, Yamada K, Yam CS, Spirn PW, Kruskal JB. Electronic messaging system for communicating important, but nonemergent, abnormal imaging results. Radiology 2010;257:724–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Laible M, Schoenberg SO, Weckbach S, et al. Whole‐body MRI and MRA for evaluation of the prevalence of atherosclerosis in a cohort of subjectively healthy individuals. Insights Imaging 2012;3:485–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baumgart D, Egelhof T. Preventive whole‐body screening encompassing modern imaging using magnetic resonance tomography. Herz 2007;32:387–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta‐analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lee SY, Park HJ, Kim MS, Rho MH, Han CH. An initial experience with the use of whole body MRI for cancer screening and regular health checks. PLoS One 2018;13:e0206681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Perkins BA, Caskey CT, Brar P, et al. Precision medicine screening using whole‐genome sequencing and advanced imaging to identify disease risk in adults. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115:3686–3691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Saya S, Killick E, Thomas S, et al. Baseline results from the UK SIGNIFY study: A whole‐body MRI screening study in TP53 mutation carriers and matched controls. Fam Cancer 2017;16:433–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ulus S, Suleyman E, Ozcan UA, Karaarslan E. Whole‐body MRI screening in asymptomatic subjects: Preliminary experience and long‐term follow‐up findings. Pol J Radiol 2016;81:407–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Schmidt CO, Sierocinski E, Hegenscheid K, Baumeister SE, Grabe HJ, Völzke H. Impact of whole‐body MRI in a general population study. Eur J Epidemiol 2016;31:31–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tarnoki DL, Tarnoki AD, Richter A, Karlinger K, Berczi V, Pickuth D. Clinical value of whole‐body magnetic resonance imaging in health screening of general adult population. Radiol Oncol 2015;49:10–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cieszanowski A, Maj E, Kulisiewicz P, et al. Non‐contrast‐enhanced whole‐body magnetic resonance imaging in the general population: The incidence of abnormal findings in patients 50 years old and younger compared to older subjects. PLoS One 2014;9:e107840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hegenscheid K, Seipel R, Schmidt CO, et al. Potentially relevant incidental findings on research whole‐body MRI in the general adult population: Frequencies and management. Eur Radiol 2013;23:816–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Puls R, Völzke H. Whole‐body MRI in the study of health in Pomerania. Radiologe 2011;51:379–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Takahara T, Kwee T, Kibune S, et al. Whole‐body MRI using a sliding table and repositioning surface coil approach. Eur Radiol 2010;20:1366–1373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morin SH, Cobbold JF, Lim AK, et al. Incidental findings in healthy control research subjects using whole‐body MRI. Eur J Radiol 2009;72:529–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hegenscheid K, Kühn JP, Völzke H, Biffar R, Hosten N, Puls R. Whole‐body magnetic resonance imaging of healthy volunteers: Pilot study results from the population‐based SHIP study. Rofo 2009;181:748–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lo GG, Ai V, Au‐Yeung KM, Chan JK, Li KW, Chien D. Magnetic resonance whole body imaging at 3 Tesla: Feasibility and findings in a cohort of asymptomatic medical doctors. Hong Kong Med J 2008;14:90–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kramer H, Schoenberg SO, Nikolaou K, et al. Cardiovascular whole body MRI with parallel imaging. Radiologe 2004;44:835–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goyen M, Goehde SC, Herborn CU, et al. MR‐based full‐body preventative cardiovascular and tumor imaging: Technique and preliminary experience. Eur Radiol 2004;14:783–791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hussain S. Communicating critical results in radiology. J Am Coll Radiol 2010;7:148–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Honig SE, Honig EL, Babiarz LB, Lewin JS, Berlanstein B, Yousem DM. Critical findings: Timing of notification in neuroradiology. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2014;35:1485–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Maclean DF, Sultana R, Radwan R, McKnight L, Khastgir J. Is the follow‐up of small renal angiomyolipomas a necessary precaution? Clin Radiol 2014;69:822–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]