Abstract

Purpose

Arginine depletion interferes with pyrimidine metabolism as well as DNA damage repair pathways. Preclinical data indicates that pairing pegylated arginine deiminase (ADI-PEG 20) with fluoropyrimidines or platinum enhances cytotoxicity in vitro and in vivo in arginine auxotrophs.

Methods

This is a single-center, open-label, phase 1 trial of ADI-PEG 20 and modified FOLFOX6 (mFOLFOX6) in treatment-refractory hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and other advanced gastrointestinal tumors. A 3 + 3 dose escalation design was employed to assess safety, tolerability, and determine the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) of ADI-PEG 20. A RP2D expansion cohort for patients with HCC was employed to define the objective response rate (ORR). Secondary objectives were to estimate progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), and to explore pharmacodynamics and immunogenicity. Eligible patients were treated with mFOLFOX6 intravenously biweekly at standard doses and ADI-PEG-20 intramuscularly weekly at 18 (Cohort 1) or 36 mg/m2 (Cohort 2 and RP2D expansion).

Results

Twenty-seven patients enrolled—23 with advanced HCC and 4 with other gastrointestinal tumors. No dose-limiting toxicities were observed in cohort 1 or 2. The RP2D for ADI-PEG 20 was 36 mg/m2 weekly with mFOLFOX6. The most common any grade adverse events (AEs) were thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, leukopenia, anemia, and fatigue. Among the 23 HCC patients, the most frequent treatment-related Grade ≥ 3 AEs were neutropenia (47.8%), thrombocytopenia (34.7%), leukopenia (21.7%), anemia (21.7%), and lymphopenia (17.4%). The ORR for this group was 21% (95% CI 7.5–43.7). Median PFS and OS were 7.3 and 14.5 months, respectively. Arginine levels were depleted with therapy despite the emergence of low levels of anti-ADI-PEG 20 antibodies. Arginine depletion at 4 and 8 weeks and archival tumoral argininosuccinate synthetase-1 levels did not correlate with response.

Conclusions

Concurrent mFOLFOX6 plus ADI-PEG-20 intramuscularly at 36 mg/m2 weekly shows an acceptable safety profile and favorable efficacy compared to historic controls. Further evaluation of this combination is warranted in advanced HCC patients.

Keywords: Hepatocellular carcinoma, ADI-PEG 20, FOLFOX, Arginine, Argininosuccinate synthetase-1, Arginine deiminase

Introduction

Arginine, a semi-essential amino acid, is an important cellular nutrient and functions as a key regulator of several immunologic and cell signaling pathways [1–3]. In normal physiology, cells extract exogenously derived arginine or synthesize arginine from citrulline via the enzymes, argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS1) and argininosuccinate lyase (ASL) [1]. Certain cancers, such as hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), are often deficient in ASS1 and are dependent exclusively on exogenous arginine for cell proliferation, growth, and survival [4]. Arginine auxotrophy observed in cancer is a critical metabolic vulnerability that has the potential to be exploited for therapeutic benefit [1, 3].

Preclinical studies in cancer models have demonstrated that arginine deprivation leads to mitochondrial dysfunction, reactive oxygen species accumulation, DNA and chromatin damage, ultimately resulting in cancer cell death [5, 6]. Experiments in vivo and in vitro have also shown that ASS1-deficient HCCs, as well as a number of solid and liquid tumors are sensitive to arginine depletion [4, 7]. To explore arginine deprivation in the clinic, arginine deiminase, the enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of arginine to citrulline, was biochemically modified with polyethylene glycol to form pegylated arginine deiminase (ADI-PEG 20) [8]. Initial studies of ADI-PEG 20 demonstrated safety, tolerability, as well as promising antitumor activity in HCC, mesotheliomas and other solid tumors [9–12]. A large randomized study of ADI-PEG 20 versus placebo in sorafenib-refractory advanced HCC patients; however, did not confirm these preliminary clinical data [13].

Emerging data show that perturbations in arginine metabolism observed in malignancy interlink affect critical cellular processes, such as pyrimidine synthesis, folate metabolism, and DNA damage repair pathways [14–16]. Arginine depletion is known to interfere with thymidylate synthase activity, and importantly ADI-PEG 20 and 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) combination treatment results in enhanced HCC cell death over monotherapy in vitro [15]. Furthermore, arginine deprivation in arginine auxotrophs, results in altered levels of critical DNA repair proteins, potentially increasing HCC susceptibility to platinum [16, 17]. These data suggest that arginine depletion might potentiate the cytotoxic effects of chemotherapeutic agents.

Despite several recent treatment advances for patients with unresectable and metastatic HCC, most patients will make progress with tyrosine kinase or immune checkpoint inhibitors [18–21]. No systemic therapies have been proven to extend overall survival in the third-line setting, thus advanced HCC patients remain a critical area of unmet need. FOLFOX is safe, tolerable, and appears to have some clinical activity in advanced HCC patients, albeit with a modest ORR (8%) [22]. We thus conducted a phase 1 study of ADI-PEG 20 in combination with modified FOLFOX6 (mFOLFOX6) in patients with advanced HCC and other gastrointestinal malignancies.

Methods

Study design

This was a single-center, open-label, phase 1 trial of ADI-PEG 20 combined with mFOLFOX6 in patients with histologically proven HCC and other gastrointestinal cancers (clinicaltrials.gov NCT02102022). A 3 + 3 dose escalation design was used to define the recommended phase 2 dose (RP2D) of the combination. Once the RP2D was established, an exploratory expansion cohort for HCC patients was used to estimate efficacy. The study was conducted in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Patients provided written informed consent.

Patients and eligibility

Patients 18 years of age or older, with histologically proven advanced gastrointestinal cancers for the dose escalation (Cohort 1 and 2) and HCC for the dose expansion were eligible. Patients had evaluable disease assessed by an radiologist blinded to the clinical care of patients by Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors version 1.1 (RECIST1.1) [23]. HCC patients were required to have progressed or have had intolerable toxicity on sorafenib, the sole standard of care at that time. Patients with pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) were required to have progressed on a gemcitabine-based regimen, while other gastrointestinal malignancies could be treatment-naïve or had progressive disease on any form of prior systemic therapies. Any number of prior treatments was allowed for all patients.

Additional criteria included Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status 0 or 1, adequate hematologic, hepatic, and renal function. Specific criteria for HCC included intact hepatic function with a Child Pugh A score. Patients with hepatitis B viremia (HBV) were required to be maintained on antiviral therapy. All patients were required to have archival tissue for ASS1 determination, and if unavailable, the investigator could opt to obtain a pretreatment biopsy.

Exclusion criteria included anticancer therapy within 4 weeks of entering the study, except radiation therapy for symptomatic treatment within 2 weeks of study entry which was then amended to 2 weeks for any anticancer treatment, ongoing toxic manifestations of previous treatments, ≥ grade 2 peripheral sensory neuropathy, symptomatic brain or spinal cord metastases, significant concomitant or uncontrolled intercurrent illness, recent major surgery, history of another primary cancer (unless treated curatively or unlikely to affect patient outcome), allergy to platinum or pegylated or Escherichia coli products, pregnancy, history of seizure disorder, and previous therapy with ADI-PEG 20.

Study treatment

Eligible patients were treated with a weekly intramuscular injection of ADI-PEG 20 at 18 (cohort 1) or 36 mg/m2 (cohort 2 and RP2D expansion) together with intravenous (IV) biweekly mFOLFOX6 (oxaliplatin 85 mg/m2 IV on day 1; leucovorin 400 mg/m2 over 2 h on day 1; 5-fluoro-uracil 400 mg/m2 IV bolus on day 1 then 1200 mg/m2 over 24 h for 2 days). Four weeks of treatment counted as one cycle. Patients continued ADI-PEG 20 and mFOLFOX6 combination treatment for 6 cycles (24 weeks). After 24 weeks, patients with clinical benefit (stable disease or better) were permitted to continue single agent ADI-PEG 20 with or without mFOLFOX6 until disease progression at the treating physician’s discretion. For cohorts 1 and 2, at least three patients were investigated at each dose level for a minimum of 4 weeks before escalation to the next dose cohort. There were no intrapatient dose escalations.

Safety evaluations

All treated patients were evaluated for safety by medical history, physical examination and laboratory testing at screening and every 2 weeks for the duration of the study. Adverse events (AE) were collected weekly prior to ADI-PEG 20 administration. AE monitoring continued for 30 days after patient completed the study.

Dose-limiting toxicities (DLTs) were assessed during cycle one as AEs that were possibly, probably, or definitely related to the combination of mFOLFOX6 and ADI-PEG-20, including grade 4 neutropenia (> 7 days duration); febrile neutropenia; symptomatic grade 3/4 anemia (requiring transfusion therapy); grade 4 thrombocytopenia; or grade 3 or 4 nonhematologic toxicity. DLT exceptions included grade 3 anorexia, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea that resolved to a lower grade with supportive treatment within 7 days; grade 3 or 4 fatigue that resolved within 5 days; alopecia; and grade 3 or 4 asymptomatic laboratory evaluations if assessed clinically insignificant by the investigator.

Efficacy evaluations

Computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with contrast for all advanced GI cancer patients, and CT including multiphasic post-contrast imaging for HCC patients were performed every 8 weeks while on study. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis were used for patients who were intolerant of contrast. Tumor measurements were recorded and assessed by RECIST1.1.

Pharmacodynamics and immunogenicity

Blood samples for the determination of arginine, citrulline, and anti-ADI-PEG 20 antibodies were collected starting at day 1 of cycle 1 and then every week up to 24 weeks. All samples were analyzed as previously described [10]. Pretreatment of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumoral tissue was assessed for ASS1 expression by immunohistochemistry. ASS1 deficiency was defined as 0 or 1 plus immunohistochemistry staining in > 50% of tumor cells, as described previously [24].

Statistics

The primary objective of the dose escalation portion of the study was to assess the safety and tolerability and to define the RP2D of combination treatment. The primary objective of the HCC expansion was to define the objective response rate (ORR). Secondary objectives were to determine progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival (OS), the pharmacodynamics and immunogenicity of combination treatment, and to explore the impact of pretreatment ASS1 expression on objective response.

For determination of the primary endpoint, safety and tolerability were assessed based on AEs graded according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03 (CTCAE 4.03). The number of events and the number of subjects were tabulated for each treatment group. For each event, patients were counted only once if they had more than 1 event reported during the treatment period, and all events were summarized using descriptive statistics. The RP2D was defined as the highest dose study for which the incidence of DLTs was less than 33%.

Upon establishment of the RP2D, an expansion cohort was used to estimate efficacy in advanced HCC patients. HCC patient who were treated at the RP2D but in the escaltion (Cohort 2), were counted for efficiacy analysis in the dose expansion. In this exploratory analysis, a single stage design was employed in which a 5% ORR was considered not promising and a 20% ORR was considered promising given the benchmark of antitumor activity for FOLFOX alone in advanced HCC patients is approximately 8%, although 79% of these patients received FOLFOX in the first-line setting [22]. The probabilities of a type I (α) error and type II (β) error were set at 0.08 and 0.18, respectively. Thus, if ≥ 3 of 21 patients had an objective response, the combination would be considered promising and worthy of further exploration. This design yields at least a 0.82 probability of a positive result if the true response rate is at least 20%. ORR was defined as the proportion of patients who exhibited a confirmed partial response (PR) or complete response (CR). Disease control rate (DCR) was defined as the proportion of subjects at each postbaseline scan who exhibited a CR, PR or stable disease (SD). Both the ORR and DCR were estimated with the exact binomial method.

PFS was defined as the time in months from the first treatment until objective tumor progression or death from any cause. OS was defined as the time in months from the first treatment until death from any cause. PFS and OS were summarized with the Kaplan–Meier method. Pharmacodynamics and immunogenicity are summarized descriptively by time point. The Kruskal–Wallis test was employed to assess the correlation between arginine depletion, defined as negative change from baseline and a level ≤ 10 μM, at 4 and 8 weeks and objective response. Fisher exact test was used to explore the impact of archival ASS1 expression on objective response. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software.

Results

Patient demographics

A total of 27 patients enrolled on the study from January 2014 to October 2017, 7 patients [3 PDAC, 3 HCC, and 1 fibrolamellar carcinoma (FLC)] in the dose escalation, and 20 HCC patients on the expansion cohort (Table 1). The study database cutoff for the data analysis was December 1st, 2017 and at that time 3 patients remained on treatment. Of the 23 advanced HCC patients, the median age was 65 (44–77) years old and 70% were male. Etiologies included non-virally mediated (57%), HCV-associated (30.4%), and HBV-associated (13.4%) HCC. Patients were ECOG PS ≤ 1, had Child–Pugh A liver function, and all failed sorafenib—10 of 23 (43.5%) had progression ≥ 2 prior therapies. Patients received a median of 1 (1–4) prior therapies.

Table 1.

Patient demographics

| HCC Cohort (N =23) | Total (N=27) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Median (range) | 64 (44–77) | 64 (30–77) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 7 (30.4%) | 10 (37.0%) |

| Male | 16 (69.6%) | 17 (63.0%) |

| Race | ||

| Non-Asian | 17 (73.9%) | 20(74.1%) |

| Asian | 2 (8.7%) | 2 (7.4%) |

| Unknown or other | 4 (17.4%) | 5 (18.5%) |

| Tumor history | ||

| Fibrolamellar | 0 | 1 (3.7%) |

| Hepatocellular | 23 (100.0%) | 23 (85.2%) |

| Pancreatic | 0 | 3 (11.1%) |

| Child–Pugh classification | ||

| A: 5–6 points | 23 (100.0%) | 23 (85.2%) |

| NA | 4 (14.8%) | |

| HCC etiology | ||

| Non-viral | 13 (56.5%) | NA |

| HCV | 7 (30.4%) | NA |

| HBV | 3 (13.0%) | NA |

| HCC characteristics | ||

| Intrahepatic | 7 (30.4%) | NA |

| Extrahepatic | 16 (69.6%) | NA |

| Portal vein involvement | 9 (39.1%) | NA |

| AJCC stage | ||

| I | 1 (4.2%) | 1 (3.7%) |

| II | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| III | 5 (21.7%) | 6 (22%) |

| IV | 17 (73.9%) | 20(74.1%) |

| Baseline AFP (ng/mL) | ||

| Median (range) | 217.4(1.9–310,469.6) | NA |

| Lines of prior systemic and previous systemic | ||

| 1 | 13 (56.5%) | 16 (59.3%) |

| 2 | 4 (17.4%) | 5 (18.5%) |

| 3 | 3 (13.0%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| 4 | 3 (13.0%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| Prior surgical resection | ||

| No | 3 (13.0%) | 3 (11.1%) |

| Yes | 20 (87.0%) | 24 (88.9%) |

| Previous radiation treatment | ||

| No | 14 (60.9%) | 16 (59.3%) |

| Yes | 9 (39.1%) | 11 (40.7%) |

Determination of the RP2D

Four patients (3 PDAC, 1 FC) enrolled in cohort 1; no DLTs were observed. One patient was replaced due to a grade 3 cardiac event NOS that occurred after 2 days of treatment. The patient presented with a syncopal episode on cycle 1, day 3. Electrocardiogram revealed transient ST depressions in anterolateral leads with non-diagnostic elevation in troponin (max 0.3, diagnostic > 0.63 mg/mL). An echocardiogram revealed mild dyskinesis of the inferior wall, which resolved on follow-up imaging. The event resolved completely but potentially represented an idiosyncratic cardiotoxicity related to 5-fluorouracil. Three HCC patients enrolled into cohort 2, no DLTs were observed. The RP2D was set at ADI-PEG 20 36 mg/m2 in combination with mFOLFOX6.

Safety and tolerability

All 27 patients were evaluable for safety and tolerability. Among the 23 HCC patients treated in cohort 2 and in the RP2D expansion, all patients reported at least 1 treatment emergent AE. The most frequent treatment emergent AEs of any grade and attribution were thrombocytopenia, neutropenia, leukopenia, anemia, and fatigue (Table 2).

Table 2.

Treatment emergent adverse events of any grade and relationship

| Cohort 1 (N=4) | Cohort 2 (N= 3) | RP2D expansion (N = 20) |

TOTAL HCC(N=23) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of adverse events | 4 | 30 | 159 | 189 |

| Patient reporting ≥ 1 AE | 3 (75%) | 3 (100%) | 20 (100%) | 23 (100%) |

| Grade 1: mild | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Grade 2: moderate | 1 (25.0%) | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Grade 3: severe | 2 (50.0%) | 3 (100.0%) | 11 (55.0%) | 14 (60.9%) |

| Grade 4: life-threatening | 0 | 0 | 4 (20.0%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Grade 5: death | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.6%) |

| Type of toxicity | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) |

| Hematologic disorders | ||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 8 (40.0%) | 12 (52.2%) |

| Neutropenia | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 10 (50.0%) | 11 (47.8%) |

| Anemia | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 6 (30.0%) | 7 (30.4%) |

| Leukopenia | 0 | 0 | 6 (30.0%) | 6 (26.1%) |

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| General disorders | ||||

| Fatigue | 0 | 2 (66.7%) | 5 (25.0%) | 7 (30.4%) |

| Edema peripheral | 0 | 0 | 4 (20.0%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Pain | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Pyrexia | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Chest pain | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Non-cardiac chest pain | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Disease progression | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Investigations | ||||

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 4 (20.0%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 0 | 0 | 4 (20.0%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 0 | 0 | 4 (20.0%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Blood alkaline phosphatase increased | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (10.0%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Lymphocyte count decreased | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (15.0%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time prolonged | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Neurologic disorder | ||||

| Encephalopathy | 0 | 0 | 5 (25.0%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Neuropathy peripheral | 0 | 2 (66.6%) | 1 (5.0%) | 3 (13.3%) |

| Metabolic disorders | ||||

| Hyperglycemia | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (15.0%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Hypoalbuminemia | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Blood creatinine increased | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Decreased appetite | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Glucose tolerance impaired | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Hyperkalemia | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Hypoglycaemia | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 1 (4.3%) |

| Hypophosphatemia | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Hyponatremia | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | ||||

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 3 (15.0%) | 3 (13.0%) |

| Abdominal pain | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Stomatitis | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 1 (4.3%) |

| Esophageal varices | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Abdominal distension | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Nausea | 1 (25.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 1 (25.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | ||||

| Dyspnea | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Cough | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Respiratory failure | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Psychiatric disorders | ||||

| Confusional state | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Depression | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | ||||

| Maculopapular rash | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Urticaria | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | ||||

| Blood creatinine increased | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Acute renal failure | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Vascular disorders | ||||

| Hypertension | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Infections and infestations | ||||

| Cellulitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Influenza | 1 (25.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | ||||

| Spinal compression fracture | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | ||||

| Muscular weakness | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 1 (4.3%) |

| Musculoskeletal chest pain | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Cardiac disorder | ||||

| Cardiac disorder NOS | 1 (25.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Seventeen of 23 (73.9%) patients experienced a grade 3 or 4 event attributed at least possibly related to the study treatment (Table 3). The most common treatment-related grade 3 or 4 AEs were neutropenia (47.8%), thrombocytopenia (34.7%), leukopenia (21.7%), anemia (21.7%), lymphopenia (17.4%), fatigue (8.7%), and encephalopathy (8.7%). Regarding the 2 cases of treatment-related grade 3 encephalopathy, both occurred within the first cycle of the study. Both instances resolved with cessation of study treatment, inpatient admission, and lactulose. One patient restarted mFOLFOX6 and ADI-PEG 20 with a dose reduction and continued treatment for an additional 7 months. The second patient recovered completely, did not receive additional treatment, and was withdrawn from the study for toxicity. The other treatment-related grade 3 or 4 events were febrile neutropenia (1), stomatitis (1), diarrhea (1), hyponatremia (1), upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (1), and transaminitis (1).

Table 3.

Related Grade ≥ 3 events to FOLFOX, ADI-PEG-20, or the combination

| Cohort 1 (N= 4) | Cohort 2 (N= 3) | RP2D expansion (N = 20) |

Total HCC (N=23) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neutropenia | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 10 (50.0%) | 11 (47.8%) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 3 (l00.0%) | 5 (25.0%) | 8 (34.7%) |

| Leukopenia | 0 | 0 | 5 (25.0%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Anemia | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 4 (20.0%) | 5 (21.7%) |

| Lymphopenia | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 3 (15.0%) | 4 (17.4%) |

| Encephalopathy | 0 | 0 | 2 (10.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Fatigue | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 1 (5.0%) | 2 (8.7%) |

| Alanine aminotrans-ferase increased | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 0 | 1 (4.3%) |

| Febrile Neutropenia | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Stomatitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Upper GI hemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Hyponatremia | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Cardiac disorder NOS | 1 (25.0%) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Among the 23 HCC patients, one or more components of ADI-PEG 20 and mFOLFOX6 were dose reduced, discontinued, or reduced and discontinued in 16 (69.6%) patients (Table 4). Dose reductions or discontinuations for toxicity included encephalopathy, diarrhea, hematologic toxicity, and/or peripheral sensory neuropathy. ADI-PEG 20 and mFOLFOX6 were maintained at full dose in 23 (100%) and 7 (30.4%) of the 23 HCC patients, respectively. Three patients died within 30 days of last treatment, 1 due to clinical deterioration and 2 due to disease progression as confirmed by cross-sectional imaging.

Table 4.

Patient disposition

| Cohort 1 (N=4) | Cohort 2 (N= 3) | MTD [1] (N = 20) | HCC [2] (N=23) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median number of cycles | 2 | 2 | 4.5 | 4 |

| Number of patients with ADI-PEG 20 dose reduction | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of patients with FOLFOX reduction Reason for study discontinuation | 2 (50%) | 3 (100%) | 13 (65%) | 16 (69.6%) |

| Reason for study discontinuation | ||||

| Adverse event | 1 (25%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Physician decision | 0 | 0 | 1 (5%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| Progressive disease | 2 (50%) | 2 (66.7%) | 15 (75%) | 17 (73.9%) |

| Withdrawal by subject | 1 (25%) | 0 | 1 (5%) | 1 (4.3%) |

| On treatment | 0 | 1 (33.3%) | 2 (10%) | 3 (13%) |

Efficacy analysis

Among the 4 patients treated in cohort 1, 2 patients (PDAC) were not evaluable—one had clinical deterioration due to disease progression, the other was replaced due to potential idiosyncratic cardiac toxicity of 5-FU. The remaining 2 patients (FLC and PDAC) had progressive disease at first interval scan.

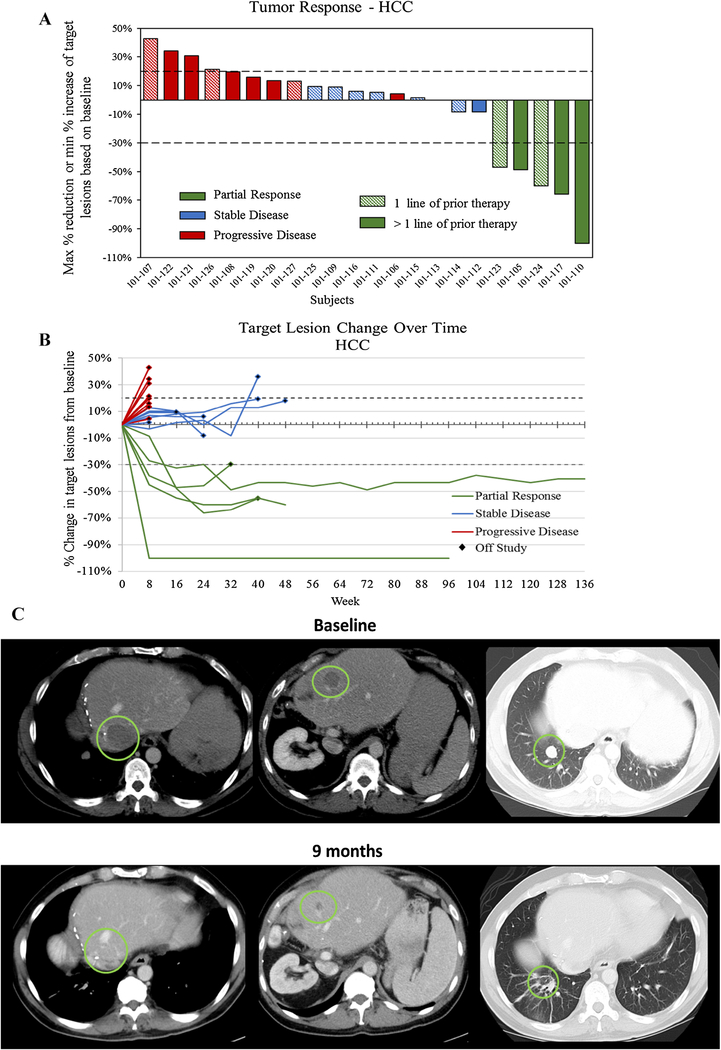

Among the 23 HCC patients enrolled into cohort 2 and the expansion cohort and treated at the RP2D, the best radiologic responses were PR in 5 (21.7%), SD in 8 (34.8%) and progressive disease in 9 (39.1%). One patient was not evaluable due to clinical deterioration (Fig. 1a). The ORR and DCR were 21.7% (95% CI 7.5–43.7) and 56.5% (95% CI 34.5–76.8%), respectively. The median duration of response was 9.5 months (range 5.6–27.6) at the time of the data cutoff—3 patients had ongoing tumoral response at 9.5, 20.5, and 27.6 months (Fig. 1b, c). Objective responses were observed in both virally mediated (2 of 10) and non-virally mediated (3 of 13) HCC patients. Among those 10 patients who had previously progressed on at least 2 prior treatments, 3 patients (30%) attained a partial response to the study treatment. Two of these patients had received prior anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies. The median PFS was 7.3 months (95% CI 1.8–11.0) and the median OS was 14.5 months (95% CI 4.0 to not reached) for the 23 HCC patients.

Fig. 1.

Response status as a waterfall and b spider plots for 22 evaluable HCC patients with ADI-PEG 20 and mFOLFOX6 and c a clinical example of a durable response in a patient with biopsy proven HCC with pulmonary metastasis

Pharmacodynamics, immunogenicity, and biomarker analysis

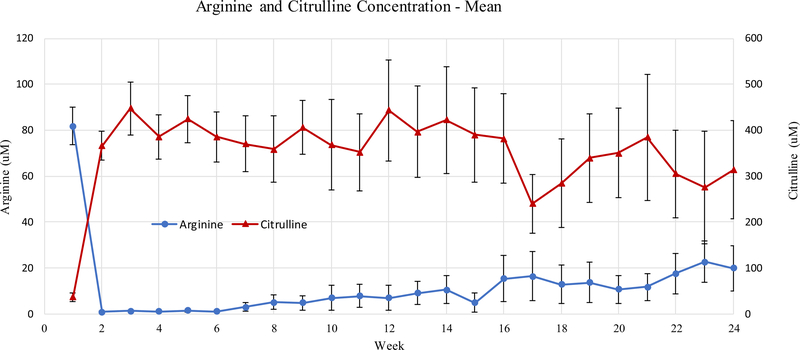

ADI-PEG 20 treatment resulted in rapid depletion of plasma arginine (Mean ± SEM, baseline 81.7 ± 7.7, week 1 0.8 ± 0.2 μM) with a reciprocal increase in plasma citrulline (Mean ± SEM, baseline 36.9 ± 8.9, week 1 369.0 ± 29.5 μM). Arginine suppression persisted throughout the course of treatment and remained suppressed at 25% of baseline levels after 24 weeks of treatment (Mean ± SEM, baseline 81.7 ± 7.7, week 24 20.5 ± 9 μM, Fig. 2). Qualitatively, arginine and citrulline levels did slowly converge over the course of treatment. Anti-ADI-PEG-20 antibody titers are shown in Fig. 3. Titers increased gradually over time though remained below 104 by week 24. No correlation between best objective response and arginine depletion at 4 (p = 0.32) and 8 weeks (p = 0.79) was observed.

Fig. 2.

Pharmacodynamic changes in the mean plasma arginine and citrulline levels by the week of study treatment for all patients

Fig. 3.

Immunogenicity of ADI-PEG-20 depicted as changes in the mean plasma anti–ADI-PEG 20 Ab titer levels by the week of study treatment for all patients

Archival tumor samples were available obtained for 27 patients on study, though for 4 patients, available tissue was insufficient for ASS1 analysis. Among the 23 HCC patients, 19 (82.6%) underwent ASS1 testing. Two of 19 (10.5%) samples were deficient. There was no correlation with ASS1 deficiency and best objective response (p = 1.0).

Discussion

ADI-PEG 20 plus mFOLFOX6 was evaluated in patients with advanced gastrointestinal cancer, with a focused expansion on patients with HCC. In an exploratory HCC expansion, the study met its pre-specified endpoint with an ORR of 21% (CI 95% 7.5–43.7) and a DCR of 56.5% (95% CI 34.5–76.8%). The median PFS and OS were 7.3 months and 14.5 months, respectively. Combination treatment resulted in sustained arginine depletion through 24 weeks, the duration of pharmacodynamic testing. Neither arginine depletion at 4 and 8 weeks nor pretreatment tumoral ASS1 expression correlated with response.

The predominant safety signal observed with this combination was hematologic toxicity, and our data are not appreciably different from data reported in prior large studies of FOLFOX in HCC and other gastrointestinal cancers in both Asian and non-Asian patients [22, 25]. In the EACH [Oxaliplatin (Eloxatin) Plus FOLFOX4 Compared With Single-Agent Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) As Palliative Chemotherapy in Advanced Hepatocellular Carcinoma Patients] study, all grade neutropenia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia occurred in 69, 59, 60, and 43% of patients, respectively [22]. The addition of ADI-PEG 20 to mFOLFOX6 did not appear to alter these frequencies—48, 39, 52, and 30%. It should be noted that the proportion of grade ≥ 3 hematologic toxicity in our study is higher than what has been observed in other studies of FOLFOX in HCC patients. It is unclear if this observation represents a true biologic phenomenon or a consequence of a small sample size. Nevertheless, all such cases were resolved and manageable with dose reductions and growth factor support. The frequency of gastrointestinal and neurologic AEs was also similar to prior studies of FOLFOX in HCC. As expected, we did identify some treatment-related grade 3 events that are likely byproducts of cirrhosis, specifically encephalopathy. These observations illustrate the complexity of drug development in the cirrhotic, will be important events to monitor with further development of this combination, and reinforce the importance of patient selection when considering systemic treatments for patients with advanced HCC [8].

The exploratory single stage HCC expansion cohort met its primary endpoint, combination therapy that led to meaningful and durable tumoral shrinkage in 21% of patients. These results compare favorably to the largest prospective experience of FOLFOX in HCC patients, where the ORR was 8%, although 79% of these patients received FOLFOX in the first-line setting [22]. The addition of platinum-based cytotoxic therapy to ADI-PEG 20 also led to an effective doubling of the response rate in a recent small study of patients with ASS1-deficient thoracic tumors [24]. Similar effective doubling of the response rate also occurred in a recent small study of ASS1-agnostic PDAC patients treated with ADI-PEG 20 and gemcitabine plus nab-paclitaxel [26]. Taken together, these data help to support the hypothesis that arginine depletion might potentiate the cytotoxic effects of certain chemotherapeutics in both ASS1-proficient and deficient cancers. The secondary endpoints of PFS (7.3 months) and OS (14.5 months) in this advanced (73% extrahepatic disease, 40% with portal vein involvement, 40% AFP ≥ 400 ng/mL) and heavily pretreated population were also favorable when compared to recent prospective studies of FOLFOX or multi-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Front-line FOLFOX in advanced HCC patients in Asia resulted in a median PFS and OS of 2.9 and 6.4 months, respectively [22]. Of course, the hazards of cross trial comparisons are well-documented, particularly in HCC where heterogeneous biology, disparate ethnicity, and geography may influence treatment outcomes. As an example, the EACH study was enriched with HBV-associated HCC (> 90%) while in comparison, only a small number of patients in our study had HBV as an etiologic factor (~ 14%), thus the paucity of HBV-associated HCC may lead to a prognostic imbalance that favors a longer PFS and OS in this cohort.

How the combination of FOLFOX6 and ADI-PEG-20 will be explored in the current landscape of treatment for HCC is intriguing. Given the emergence of two TKIs (regorafenib and cabozantinib [18, 27]) and one monoclonal antibody (ramucirumab [28]) with a survival advantage over best supportive care in the second-line, and the durable response rate of nivolumab in patients who failed sorafenib [20], a logical drug development strategy for the proposed therapy is in the 3rd-line space as a salvage therapy. Indeed, 43% of our study population failed at least 2 lines of prior treatment, including anti-PD-1 therapy, and sustained radiographic responses were still observed in this patient population.

Pharmacodynamic data indicate that ADI-PEG 20 depleted plasma arginine for the entirety of the 24-week treatment period to levels below 25% of baseline. This contrasts with prior reports with ADI-PEG 20 monotherapy in HCC where arginine and citrulline concentrations normalized between 8 and 12 weeks [10, 11]. It is possible that this is a result of suppression of neutralizing antibodies, and the qualitative rise in anti-ADI-PEG 20 titers over treatment appeared slower then what has been reported previously. Similar effects have been observed with combination chemotherapy and ADI-PEG 20 in patients with advanced mesothelioma, non-small cell lung cancer, and PDAC, and a potential hypothesis for differential pharmacodynamic data is that the immunosuppressive effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy and/or supportive corticosteroids may lead to anti-drug antibody suppression [24, 26]. Despite rapid and sustained arginine depletion, arginine depletion at 4 and 8 weeks did not appear to correlate with clinical benefit. This finding is not surprising given that arginine concentrations were effectively depleted for the entire study period in most patients. Furthermore, pretreatment tumoral ASS1 levels did not correlate with radiographic response. Of course, this may be a function of the relatively small sample size, or the known difficulties using archival tissue to assess for ASS1 levels [13]. In addition, systemic treatments administered after obtaining the archival sample may also have altered ASS1 levels [29]. Alternatively, given the use of combination treatment, ASS1 deficiency may not be required for a response to treatment when ADI-PEG 20 is part of combination systemic therapy. Indeed, even with ASS1 proficiency, a tumor cell must opt to use aspartate to make arginine and urea, or to make nucleotides and attempt to repair DNA damage caused by agents such as platinums and antifolates to avoid death.

In sum, the combination of ADI-PEG 20 plus mFOLFOX6 was safe and tolerable. The RP2D was defined as ADI-PEG 20 at 36 mg/m2 IM weekly with standard dose mFOLFOX6. The combination exhibited encouraging preliminary efficacy in treatment-refractory HCC patients, and is therefore worthy of further exploration. The small sample size accrued at one center is a limitation of the study, and may lead to selection bias or an incorrect estimation of efficacy and/or toxicity. Thus, a large, international, multicenter, phase 2 trial to confirm these findings in a more diverse patient population who have failed 2 lines of prior therapy is ongoing.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Marinela Capanu for her critical review of the manuscript.

Funding The trial was funded by Polaris Pharmaceuticals, Inc. This research was also funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest Xiaoxing Feng, Amanda Johnston, and John Bomalaski are employees of Polaris Pharmaceuticals Inc. There are no other conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

References

- 1.Patii MD, Bhaumik J, Babykutty S, Banerjee UC, Fukumura D (2016) Arginine dependence of tumor cells: targeting a chink in cancer’s armor. Oncogene 35(38):4957–4972. 10.1038/onc.2016.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray PJ (2016) Amino acid auxotrophy as a system of immunological control nodes. Nat Immunol 17(2):132–139. 10.1038/ni.3323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Peiris-Pages M, Pestell RG, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP (2017) Cancer metabolism: a therapeutic perspective. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 14(1):11–31. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ensor CM, Holtsberg FW, Bomalaski JS, Clark MA (2002) Pegylated arginine deiminase (ADI-SS PEG20,000 mw) inhibits human melanomas and hepatocellular carcinomas in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res 62(19):5443–5450 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kremer JC, Prudner BC, Lange SES, Bean GR, Schultze MB, Brashears CB, Radyk MD, Redlich N, Tzeng SC, Kami K, Shelton L, Li A, Morgan Z, Bomalaski JS, Tsukamoto T, McConathy J, Michel LS, Held JM, Van Tine BA (2017) Arginine deprivation inhibits the Warburg effect and upregulates glutamine anaplerosis and serine biosynthesis in ASS1-deficient cancers. Cell Rep 18(4):991–1004. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.12.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Changou CA, Chen YR, Xing L, Yen Y, Chuang FY, Cheng RH, Bold RJ, Ann DK, Kung HJ (2014) Arginine starvation-associated atypical cellular death involves mitochondrial dysfunction, nuclear DNA leakage, and chromatin autophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(39): 14147–14152. 10.1073/pnas.1404171111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miraki-Moud F, Ghazaly E, Ariza-McNaughton L, Hodby KA, Clear A, Anjos-Afonso F, Liapis K, Grantham M, Sohrabi F, Cavenagh J, Bomalaski JS, Gribben JG, Szlosarek PW, Bonnet D, Taussig DC (2015) Arginine deprivation using pegylated arginine deiminase has activity against primary acute myeloid leukemia cells in vivo. Blood 125(26):4060–4068. 10.1182/blood-2014-10-608133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harding JJ, Abou-Alfa GK (2014) Treating advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: How to get out of first gear. Cancer 120(20):3122–3130. 10.1002/cncr.28850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Izzo F, Marra P, Beneduce G, Castello G, Vallone P, De Rosa V, Cremona F, Ensor CM, Holtsberg FW, Bomalaski JS, Clark MA, Ng C, Curley SA (2004) Pegylated arginine deiminase treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: results from phase I/II studies. J Clin Oncol 22(10):1815–1822. 10.1200/JC0.2004.11.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glazer ES, Piccirillo M, Albino V, Di Giacomo R, Palaia R, Mastro AA, Beneduce G, Castello G, De Rosa V, Petrillo A, Ascierto PA, Curley SA, Izzo F (2010) Phase II study of pegylated arginine deiminase for nonresectable and metastatic hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 28(13):2220–2226. 10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang TS, Lu SN, Chao Y, Sheen IS, Lin CC, Wang TE, Chen SC, Wang JH, Liao LY, Thomson JA, Wang-Peng J, Chen PJ, Chen LT (2010) A randomised phase II study of pegylated arginine deiminase (ADI-PEG 20) in Asian advanced hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Br J Cancer 103(7):954–960. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Szlosarek PW, Steele JP, Nolan L, Gilligan D, Taylor P, Spicer J, Lind M, Mitra S, Shamash J, Phillips MM, Luong P, Payne S, Hillman P, Ellis S, Szyszko T, Dancey G, Butcher L, Beck S, Avril NE, Thomson J, Johnston A, Tomsa M, Lawrence C, Schmid P, Crook T, Wu BW, Bomalaski JS, Lemoine N, Sheaff MT, Rudd RM, Fennell D, Hackshaw A (2017) Arginine deprivation with pegylated arginine deiminase in patients with argininosuccinate synthetase 1-deficient malignant pleural mesothelioma: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 3(1):58–66. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.3049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abou-Alfa GK, Qin S, Ryoo B-Y, Lu S-N, Yen C-J, Feng Y-H, Lim HY, Izzo F, Colombo M, Sarker D, Bolondi L, Vaccaro GM, Harris WP, Chen Z, Hubner R, Meyer T, Bomalaski JS, Lin C, Chao Y, Chen L-T (2018) Phase III randomized study of second line ADI-PEG 20 plus best supportive care versus placebo plus best supportive care in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol 29(6):1402–1408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rabinovich S, Adler L, Yizhak K, Sarver A, Silberman A, Agron S, Stettner N, Sun Q, Brandis A, Helbling D, Korman S, Itzkovitz S, Dimmock D, Ulitsky I, Nagamani SC, Ruppin E, Erez A (2015) Diversion of aspartate in ASS1-deficient tumours fosters de novo pyrimidine synthesis. Nature 527(7578):379–383. 10.1038/nature15529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thongkum A, Wu C, Li YY, Wangpaichitr M, Navasumrit P, Parnlob V, Sricharunrat T, Bhudhisawasdi V, Ruchirawat M, Savaraj N (2017) The combination of arginine deprivation and 5-fluorouracil improves therapeutic efficacy in argininosuccinate synthetase negative hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 10.3390/ijms18061175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAlpine JA, Lu HT, Wu KC, Knowles SK, Thomson JA (2014) Down-regulation of argininosuccinate synthetase is associated with cisplatin resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines: implications for PEGylated arginine deiminase combination therapy. BMC Cancer 14:621 10.1186/1471-2407-14-621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Savaraj N, Wu C, Li YY, Wangpaichitr M, You M, Bomalaski J, He W, Kuo MT, Feun LG (2015) Targeting argininosuccinate synthetase negative melanomas using combination of arginine degrading enzyme and cisplatin. Oncotarget 6(8):6295–6309. 10.18632/oncotarget.3370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruix J, Qin S, Merle P, Granito A, Huang YH, Bodoky G, Pracht M, Yokosuka O, Rosmorduc O, Breder V, Gerolami R, Masi G, Ross PJ, Song T, Bronowicki JP, Ollivier-Hourmand I, Kudo M, Cheng AL, Llovet JM, Finn RS, LeBerre MA, Baumhauer A, Meinhardt G, Han G, Investigators R (2017) Regorafenib for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who progressed on sorafenib treatment (RESORCE): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389(10064):56–66. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32453-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, de Oliveira AC, Santoro A, Raoul JL, Forner A, Schwartz M, Porta C, Zeuzem S, Bolondi L, Greten TF, Galle PR, Seitz JF, Borbath I, Haussinger D, Giannaris T, Shan M, Moscovici M, Voliotis D, Bruix J, Group SIS (2008) Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med 359(4):378–390. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Khoueiry AB, Sangro B, Yau T, Crocenzi TS, Kudo M, Hsu C, Kim TY, Choo SP, Trojan J, Welling THR, Meyer T, Kang YK, Yeo W, Chopra A, Anderson J, Dela Cruz C, Lang L, Neely J, Tang H, Dastani HB, Melero I (2017) Nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (CheckMate 040): an open-label, non-comparative, phase 1/2 dose escalation and expansion trial. Lancet 389(10088):2492–2502. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31046-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng A-L, Finn RS, Qin S, Han K-H, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, Baron AD, Park J-W, Han G, Jassem J, Blanc J-F, Vogel A, Komov D, Evans TRJ, López-López C, Dutcus CE, Ren M, Kraljevic S, Tamai T, Kudo M (2017) Phase III trial of lenvatinib (LEN) vs sorafenib (SOR) in first-line treatment of patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (uHCC). J Clin Oncol 35(15_suppl):4001–4001. 10.1200/JC0.2017.35.15_suppl.4001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Qin S, Bai Y, Lim HY, Thongprasert S, Chao Y, Fan J, Yang TS, Bhudhisawasdi V, Kang WK, Zhou Y, Lee JH, Sun Y (2013) Randomized, multicenter, open-label study of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin versus doxorubicin as palliative chemotherapy in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma from Asia. J Clin Oncol 31(28):3501–3508. 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.5643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M, Rubinstein L, Shankar L, Dodd L, Kaplan R, Lacombe D, Verweij J (2009) New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 45(2):228–247. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Beddowes E, Spicer J, Chan PY, Khadeir R, Corbacho JG, Repana D, Steele JP, Schmid P, Szyszko T, Cook G, Diaz M, Feng X, Johnston A, Thomson J, Sheaff M, Wu BW, Bomalaski J, Pacey S, Szlosarek PW (2017) Phase 1 dose-escalation study of pegylated arginine deiminase, cisplatin, and pemetrexed in patients with argininosuccinate synthetase 1-deficient thoracic cancers. J Clin Oncol 35(16):1778–1785. 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberg RM, Tabah-Fisch I, Bleiberg H, de Gramont A, Tournigand C, Andre T, Rothenberg ML, Green E, Sargent DJ (2006) Pooled analysis of safety and efficacy of oxaliplatin plus fluorouracil/leucovorin administered bimonthly in elderly patients with colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol 24(25):4085–4091. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.9039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowery MA, Yu KH, Kelsen DP, Harding JJ, Bomalaski JS, Glassman DC, Covington CM, Brenner R, Hollywood E, Barba A, Johnston A, Liu KC, Feng X, Capanu M, Abou-Alfa GK, O’Reilly EM (2017) A phase 1/1B trial of ADI-PEG 20 plus nab-paclitaxel and gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer 123(23):4556–4565. 10.1002/cncr.30897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abou-Alfa GK, Meyer T, Cheng A-L, El-Khoueiry AB, Rimassa L, Ryoo B-Y, Cicin I, Merle P, Park J-W, Blanc J-F, Bolondi L, Klümpen HJ, Chan SL, Dadduzio V, Hessel C, Borgman-Hagey AE, Schwab G, Kelley RK (2018) Cabozantinib (C) versus placebo (P) in patients (pts) with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) who have received prior sorafenib: Results from the randomized phase III CELESTIAL trial. J Clin Oncol 36(4_suppl):207 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.4_suppl.207 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhu AX, Kang Y-K, Yen C-J, Finn RS, Galle PR, Llovet JM, Assenat E, Brandi G, Lim HY, Pracht M, Rau K-M, Merle P, Motomura K, Ohno I, Daniele B, Shin D, Gerken G, Abada P, Hsu Y, Kudo M (2018) REACH-2: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study of ramucirumab versus placebo as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and elevated baseline alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) following first-line sorafenib. J Clin Oncol 36(15_suppl):4003–4003. 10.1200/JCO.2018.36.15_suppl.4003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nicholson LJ, Smith PR, Hiller L, Szlosarek PW, Kimberley C, Sehouli J, Koensgen D, Mustea A, Schmid P, Crook T (2009) Epigenetic silencing of argininosuccinate synthetase confers resistance to platinum-induced cell death but collateral sensitivity to arginine auxotrophy in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer 125(6):1454–1463. 10.1002/ijc.24546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]