Abstract

It is postulated that testosterone-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy is driven by myonuclear accretion as the result of satellite cell fusion. To directly test this hypothesis, we utilized the Pax7-DTA mouse model to deplete satellite cells in skeletal muscle followed by testosterone administration. Pax7-DTA mice (6 mo of age) were treated for 5 days with either vehicle [satellite cell replete (SC+)] or tamoxifen [satellite cell depleted (SC-)]. Following a washout period, a testosterone propionate or sham pellet was implanted for 21 days. Testosterone administration caused a significant increase in muscle fiber cross-sectional area in SC+ and SC- mice in both oxidative (soleus) and glycolytic (plantaris and extensor digitorum longus) muscles. In SC+ mice treated with testosterone, there was a significant increase in both satellite cell abundance and myonuclei that was completely absent in testosterone-treated SC- mice. These findings provide direct evidence that testosterone-induced muscle fiber hypertrophy does not require an increase in satellite cell abundance or myonuclear accretion.

Listen to a podcast about this Rapid Report with senior author E. E. Dupont-Versteegden (https://ajpcell.podbean.com/e/podcast-on-paper-that-shows-testosterone-induced-skeletal-muscle-hypertrophy-does-not-need-muscle-stem-cells/).

Keywords: hypertrophy, satellite cell, skeletal muscle, stem cell, testosterone

INTRODUCTION

Satellite cells are required for postnatal skeletal muscle growth and regeneration, but their role during periods of adult skeletal muscle hypertrophy remains to be fully elucidated (10, 13, 17, 20). Most studies that have investigated the requirement for satellite cells during hypertrophic growth in both juvenile and mature mice have utilized the surgical synergist ablation model to induce hypertrophy, which is supraphysiological and nonreversible (5–7, 10, 11, 14). These studies have shown that satellite cells are required for muscle hypertrophy before complete skeletal muscle maturation (<4 mo of age; 5, 7, 11, 14). In mature skeletal muscle, considerable muscle growth can occur over a relatively short time frame in the absence of satellite cell-dependent myonuclear accretion; however, satellite cells are required for sustained periods of muscle growth (6, 10, 14). To further our understanding of satellite cell-mediated muscle hypertrophy, we utilized the Pax7-DTA mouse model to enable depletion of satellite cells and a pharmacological approach to induce muscle hypertrophy. We chose continuous-release (21 days) testosterone pellet implantation as our treatment strategy since high doses of testosterone have been consistently shown to promote an increase in muscle fiber cross-sectional area (CSA), myonuclear number, and satellite cell content (4, 21, 22).

There are multiple mechanisms by which testosterone treatment has been reported to stimulate muscle hypertrophy (3, 18, 19, 22). The primary mechanism is dependent on androgen receptor (AR) content to induce androgen-stimulated increases in protein synthesis (1, 12). Once bound by testosterone, the AR is released from the membrane to induce genomic and nongenomic actions that include increasing IGF-1 expression, Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 phosphorylation events, and subsequent elevated protein synthesis (1, 25, 26). It is well documented that muscle fibers, satellite cells, and other mononuclear cell populations (fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and mast cells) found within skeletal muscle all express the AR; in particular, testosterone treatment of satellite cells in vitro induces a 25% increase in proliferation, and global knockout of the AR in mice alters regulators of proliferation and differentiation (9, 16, 23). Although testosterone administration induces satellite cell proliferation and muscle growth, more work is needed to determine the direct relationship between increased satellite cell content and muscle hypertrophy in response to testosterone (16, 19).

On the basis of the effects of testosterone on satellite cell proliferation and fusion and indirect evidence in humans and in mice demonstrating a relationship between myonuclear accretion and increased muscle size, the general consensus is that testosterone-induced muscle hypertrophy is driven directly by satellite cell activation and subsequent myonuclear accretion; however, direct evidence to support this consensus is currently lacking (21, 22). We therefore set out to test the hypothesis that testosterone-induced myonuclear accretion by satellite cells is required for skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Female Pax7-DTA mice were treated with vehicle [satellite cell replete (SC+)], to serve as controls, or tamoxifen [satellite cell depleted (SC-)] and were supplied with testosterone propionate or sham pellets for 21 days, after which hindlimb muscles were isolated and analyzed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

The Pax7CreER/+-R26RDTA/+ strain, called Pax7-DTA, was generated by crossing the Pax7CreER/CreER mouse strain with the Rosa26DTA/DTA mouse strain (15). The Pax7-DTA mouse allows for the specific and inducible depletion of satellite cells upon tamoxifen treatment, through Cre-mediated activation of the diphtheria toxin A gene in Pax7-expressing cells (10). Mice were housed at 14:10-h light-dark cycle and had access to water and food ad libitum. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Kentucky.

Experimental design.

Thirty-two mature (6-mo-old) female Pax7-DTA mice were treated via intraperitoneal injection with either vehicle (15% ethanol in sunflower seed oil) or tamoxifen at a dose of 2.5 mg/day for 5 days (10). Following a 2-wk washout period, either 2.5 mg testosterone propionate pellet or sham pellet, with a release time of 21 days (A-211; Innovative Research of America), was implanted subcutaneously into the lateral side of the neck with a precision trocar (MP-182; Innovative Research of America) under anesthesia (1–2% inhaled isoflurane). After 21 days, mice were euthanized and muscles [plantaris, soleus, and extensor digitorum longus (EDL)] were excised, weighed, and then pinned to a cork at resting length and covered with Tissue-Tek optimum cutting temperature compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA), frozen in liquid nitrogen-cooled isopentane, and stored at −80°C.

Testosterone enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

To determine the efficacy of the testosterone pellets, eight mice were implanted with either sham (n = 3) or testosterone (n = 5) pellets. Three days after implantation, mice were euthanized, and blood draws were conducted under light anesthesia (1–2% inhaled isoflurane). Blood samples were spun at 2,000 g for 15 min. Serum was collected and analyzed using Mouse/Rat Testosterone ELISA (ALPCO, Salem, NH) per the manufacturer’s protocol.

Immunohistochemistry.

Immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses for determination of cross-sectional area (CSA) and myonuclear number were performed as previously described (14). Frozen muscle samples were sectioned at the midbelly of the muscle at −23°C (7 µm), air-dried, and stored at −20°C. For determining muscle fiber CSA and myonuclear density, cross sections were incubated overnight in an anti-dystrophin antibody (1:100, ab-15277; Abcam, St. Louis, MO). Sections were incubated with a secondary antibody (1:150, anti-rabbit IgG, CI-1000; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Sections were mounted using Vectashield with DAPI (H-1200; Vector Laboratories).

Detection of Pax7+ cells was performed as previously described (10). Sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde followed by antigen retrieval. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% hydrogen peroxide in PBS followed by a blocking step with 1% tyramide signal amplification (TSA) blocking reagent (TSA kit, T-20935; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and Mouse-on-Mouse blocking reagent (Vector Laboratories). Pax7 primary antibody (1:100; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, IA) and laminin primary antibody (1:100; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were diluted in 1% TSA blocking buffer and applied overnight. Samples were then incubated with an isotype-specific anti-mouse biotin-conjugated secondary antibody against the Pax7 primary antibody (1:1,000, 115-065-205; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) and anti-rabbit secondary antibody for laminin (1:250, A-11034, Alexa Fluor 488; Invitrogen). Slides were washed in PBS followed by streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (1:500, S-911; Invitrogen) for 1 h. Alexa Fluor 594 was used to visualize antibody binding for Pax7 (1:100, TSA kit; Invitrogen). Sections were mounted, and nuclei were stained with Vectashield with DAPI (H-1200; Vector Laboratories).

Image quantification.

All images were captured at ×20 magnification at room temperature using a Zeiss AxioImager M1 upright fluorescent microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Whole muscle sections were obtained using the mosaic function in Zeiss Zen 2.3 imaging software (Zeiss). To minimize bias and increase reliability, muscle fiber CSA and myonuclear number were quantified on cross sections using MyoVision automated analysis software (24). MyoVision enables muscle fibers and myonuclei in the whole muscle cross section to be counted and quantified for measures of CSA and myonuclei per fiber (24). To determine satellite cell density (Pax7+ cells per fiber), satellite cells (Pax7+/DAPI+) were counted manually on entire muscle cross sections using tools in the Zen software. Satellite cell counts were normalized to fiber number via laminin. All manual counting was performed by a blinded, trained technician.

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SE. Data were analyzed with GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) via a two-factor ANOVA for Pax7+ cells per fiber, muscle weight, mean fiber CSA, and myonuclei per fiber and a two-factor repeated-measures ANOVA for body weight over time. When interactions were detected, post hoc comparisons were made with Holm-Šidák post hoc tests. Serum testosterone levels were compared using an unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test. Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Testosterone pellet implantation leads to higher satellite cell content in SC+ mice.

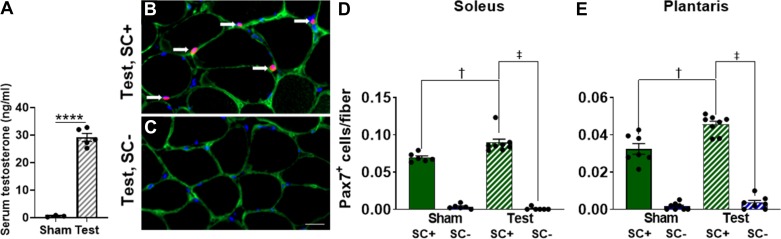

The implantation of testosterone pellets resulted in significantly higher levels of serum testosterone, measured in a subgroup of mice 3 days after implantation of the pellet (Fig. 1A). A representative image of IHC detection of Pax7-positive cells in the soleus muscle is shown in Fig. 1B. IHC image quantification demonstrated effective depletion in the soleus following tamoxifen treatment (Fig. 1C). Tamoxifen treatment effectively depleted satellite cells in the oxidative soleus (Fig. 1D) and the glycolytic plantaris (Fig. 1E). Three weeks of testosterone administration led to higher satellite cell number in soleus (22%, P = 0.007) and plantaris (29%, P < 0.001) from SC+, but not SC-, mice (Fig. 1, D and E).

Fig. 1.

Higher serum testosterone (Test) and higher satellite cell density in vehicle (satellite cell replete, SC+) compared with tamoxifen-treated (satellite cell depleted, SC-) mice after Test administration. A: serum Test concentration after 3 days of Test or Sham administration. B and C: representative images of satellite cell immunohistochemistry in the soleus showing laminin (green) nuclei (blue) and paired-box protein Pax-7 (Pax7, red; white arrows). Scale bar = 20 µm. D and E: satellite cell density in the soleus and plantaris, respectively. Data represent means ± SE; n = 6–8 mice per group. †P < 0.05, Test SC+ vs. Sham SC+; ‡P < 0.05, Test SC+ vs. Test SC-; ****P < 0.0001, Test (n = 5) vs. Sham (n = 3) mice at 3 days.

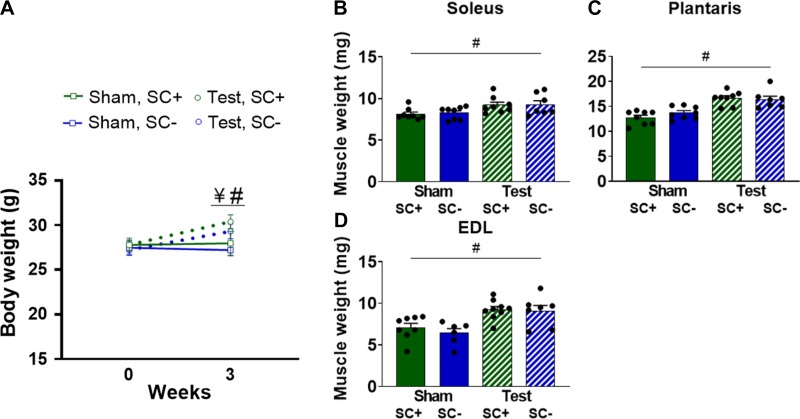

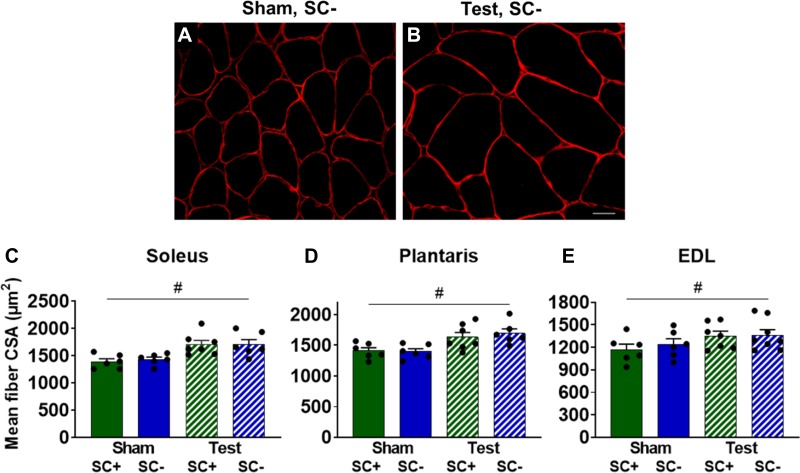

Testosterone administration induces higher whole body weight, muscle weights, and muscle fiber CSA, independent of satellite cell content.

Three weeks of testosterone administration led to a significant increase in body weight (P = 0.044), resulting in a higher body weight compared with sham-treated mice (P = 0.023; Fig. 2A) and higher soleus (P = 0.023), plantaris (P < 0.001), and EDL (P < 0.001) wet weights (Fig. 2, B, C, and D, respectively), independent of satellite cell content. Representative images of plantaris muscle immunoreacted with an antibody against dystrophin to measure CSA are shown in Fig. 3, A and B. Testosterone led to higher muscle fiber CSA in the soleus (17%, P = 0.002), plantaris (16%, P = 0.001), and EDL (14%, P = 0.038) regardless of the presence of satellite cells (Fig. 3, C–E, respectively).

Fig. 2.

Testosterone (Test) increases whole body and muscle weight in mice with [satellite cell replete (SC+)] or without [satellite cell depleted (SC-)] satellite cells. A: body weight at baseline and after 3 wk of Test or Sham administration. B–D: muscle wet weights in the soleus, plantaris, and extensor digitorum longus (EDL), respectively. Data represent means ± SE; n = 6–8 mice per group. ¥P < 0.05, within group change over time in Test-treated mice; #P < 0.05, Test vs. Sham mice at 3 wk.

Fig. 3.

Testosterone (Test) leads to greater muscle fiber size independent of satellite cell content. A and B: representative images of muscle fiber cross-sectional area (CSA) in the plantaris visualized with an antibody against dystrophin. Scale bar = 20 µm. C–E: mean fiber CSA in the soleus, plantaris, and extensor digitorum longus (EDL), respectively. Data represent means ± SE; n = 6–8 mice per group. SC+, satellite cell replete; SC-, satellite cell depleted. #P < 0.05, Test vs. Sham mice.

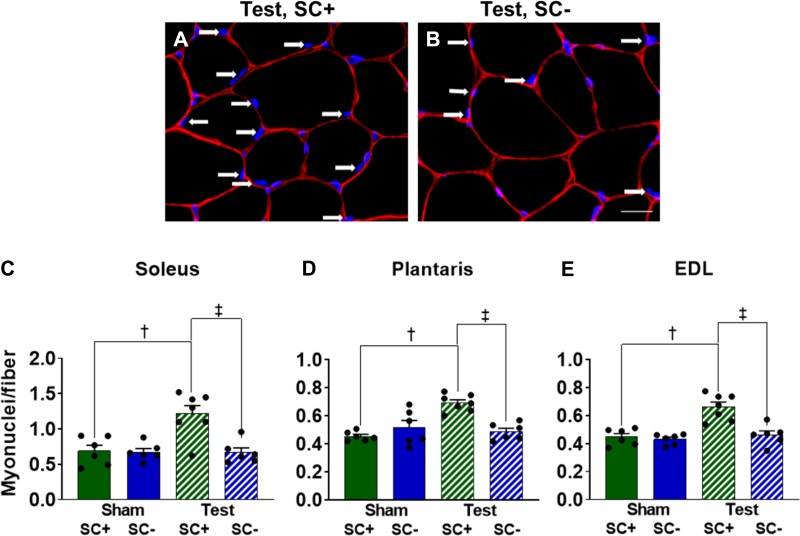

Myonuclear addition in response to testosterone administration is dependent on the presence of satellite cells.

Representative images of soleus muscle immunoreacted with an antibody against dystrophin and DAPI staining to determine myonuclear number are shown in Fig. 4, A and B. Myonuclear density was higher in the soleus (43%, P < 0.001), plantaris (32%, P < 0.001), and EDL (31%, P < 0.001) muscles of testosterone-treated SC+ mice (Fig. 4, C–E). In mice depleted of satellite cells, no myonuclear accretion occurred with testosterone treatment, which did not affect growth, as SC- mice exhibited the same hypertrophic response to testosterone as SC+ mice (see Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 4.

Elevated myonuclear number in response to testosterone (Test) is dependent on satellite cell content. A and B: representative images of dystrophin immunohistochemistry (red) and DAPI (blue) staining from soleus cross sections to identify myonuclei (white arrows). Scale bar = 20 µm. C–E: myonuclear density of the soleus, plantaris, and extensor digitorum longus (EDL), respectively. Data represent means ± SE; n = 6–7 mice per group. SC+, satellite cell replete; SC-, satellite cell depleted. †P < 0.05, Test SC+ vs. Sham SC+; ‡P < 0.05, Test SC+ vs. Test SC-.

DISCUSSION

This study reports the novel finding that neither the presence of satellite cells nor myonuclear addition via satellite cell fusion are required for testosterone-induced muscle hypertrophy, contrary to our hypothesis. It has previously been hypothesized that satellite cells play a direct role in stimulating muscle hypertrophy in response to testosterone (21, 22). However, the findings of the present study demonstrate that the hypertrophic response to testosterone is unaffected by absence of satellite cells arguing against such a mechanism. It is also worth noting that testosterone administration did not lead to the accrual of myonuclei through fusion of an extraneous stem cell population in tamoxifen-treated muscle, as evidenced by the lack of myonuclear addition in satellite cell-depleted mice treated with testosterone.

Our report supports the finding of Egner et al. that robust myonuclear accretion is observed in response to testosterone administration in muscles that have a full complement of satellite cells (4). Interestingly, the hypertrophic growth response noted by Egner et al. (~77% hypertrophy in the soleus) greatly exceeds what we report here (~17% hypertrophy in the soleus). This discrepancy is most likely due to differences in the skeletal muscle maturity of the mice used at the onset of testosterone administration. We utilized fully mature 6-mo-old mice, resulting in a correspondingly larger mean muscle fiber CSA (~1,400 µm) in sham-treated mice than in those used by Egner et al. (mean muscle fiber CSA ~1,000 µm; 4). It therefore seems likely that skeletal muscle maturation in combination with testosterone administration acted synergistically to augment muscle fiber growth in the report by Egner et al. (4).

It is currently unknown whether the higher number of satellite cells and myonuclei observed after testosterone administration is driven by a direct effect of androgen action on the satellite cells or an indirect effect from increased levels of androgen acting directly on the muscle fiber (e.g., elevated IGF-1 expression; 25). On the basis of our findings, it is apparent that testosterone increases satellite cell abundance and myonuclear content, providing further evidence for the proliferative effects of testosterone on satellite cells, either directly or indirectly. Our findings in satellite cell-depleted mice also demonstrate that the genomic and/or nongenomic actions of testosterone within the muscle fibers are sufficient to drive skeletal muscle hypertrophy (1, 25, 26). This finding is supported by a study in rat myotubes in vitro, in which no change in myonuclear number occurred following 12 h of testosterone administration despite the reported 35% higher myotube diameter than in vehicle-treated cells (1). Furthermore, our laboratory has shown that satellite cells are not required for an increase in the activation of the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, and others have shown that muscle fiber hypertrophy resulting from the overexpression of Akt occurs without satellite cell participation (2, 10). The importance of testosterone activity directly on the muscle fiber itself seems to be somewhat lost in the literature, as many groups have hypothesized that increases in skeletal muscle size are a direct consequence of satellite cell fusion and not the transcriptional activity of resident myonuclei (22). This is an important concept, since mechanisms internal to the muscle fiber should also be considered, particularly in designing interventions to increase muscle size. In line with this, we previously showed that resident myonuclei appear to have a transcriptional reserve capacity that can compensate for lack of satellite cells, enabling hypertrophy in response to synergist ablation (8a). We show here that resident myonuclei also appear to be able to compensate in satellite-depleted muscle to enable hypertrophy in response to testosterone administration. Interestingly, it is known that satellite cells are required to support sustained periods of muscle growth in response to mechanical overload (5). Whether satellite cells are also required for continued muscle growth in response to testosterone is currently unknown. Emerging technology and novel transgenic mouse models will allow for future in-depth analysis of resident myonuclei during periods of skeletal muscle growth (8). In particular, the transcriptional profile of resident myonuclei in response to a hypertrophic stimulus in the absence of satellite cell fusion is of interest.

In summary, this paper provides novel insight into the role of satellite cells in the muscle growth response to testosterone. Although testosterone normally increases satellite cell number and promotes myonuclear accretion during hypertrophy, satellite cell-dependent myonuclear accretion is not required in adult muscle for hypertrophic muscle growth. Thus, understanding the compensatory mechanism that enables healthy adult resident myonuclei to support growth in the absence of satellite cells may point to new targets for intervention in conditions where satellite cell abundance and/or activity decline and growth is compromised, such as aging.

GRANTS

This work was supported by funds from the Endowed University Professorship in Health Sciences, University of Kentucky, and NIH National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases Grant AR060701 to C. A. Peterson and J. J. McCarthy and Grant AR071753 to K. A. Murach. The project described was also supported by NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through Grant TL1 TR001997 (to D. A. Englund).

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

D.A.E., B.D.P., and E.E.D.-V. conceived and designed research; D.A.E., B.D.P., K.A.M., A.C.N., and H.A.C. performed experiments; D.A.E. and B.D.P. analyzed data; D.A.E., B.D.P., K.A.M., A.C.N., H.A.C., J.J.M., C.A.P., and E.E.D.-V. interpreted results of experiments; D.A.E., B.D.P., A.C.N., and H.A.C. prepared figures; D.A.E. and B.D.P. drafted manuscript; D.A.E., B.D.P., K.A.M., J.J.M., C.A.P., and E.E.D.-V. edited and revised manuscript; D.A.E., B.D.P., K.A.M., A.C.N., H.A.C., J.J.M., C.A.P., and E.E.D.-V. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basualto-Alarcón C, Jorquera G, Altamirano F, Jaimovich E, Estrada M. Testosterone signals through mTOR and androgen receptor to induce muscle hypertrophy. Med Sci Sports Exerc 45: 1712–1720, 2013. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31828cf5f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaauw B, Canato M, Agatea L, Toniolo L, Mammucari C, Masiero E, Abraham R, Sandri M, Schiaffino S, Reggiani C. Inducible activation of Akt increases skeletal muscle mass and force without satellite cell activation. FASEB J 23: 3896–3905, 2009. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-131870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambon C, Duteil D, Vignaud A, Ferry A, Messaddeq N, Malivindi R, Kato S, Chambon P, Metzger D. Myocytic androgen receptor controls the strength but not the mass of limb muscles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 14327–14332, 2010. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009536107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Egner IM, Bruusgaard JC, Eftestøl E, Gundersen K. A cellular memory mechanism aids overload hypertrophy in muscle long after an episodic exposure to anabolic steroids. J Physiol 591: 6221–6230, 2013. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2013.264457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Egner IM, Bruusgaard JC, Gundersen K. Satellite cell depletion prevents fiber hypertrophy in skeletal muscle. Development 143: 2898–2906, 2016. doi: 10.1242/dev.134411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fry CS, Lee JD, Jackson JR, Kirby TJ, Stasko SA, Liu H, Dupont-Versteegden EE, McCarthy JJ, Peterson CA. Regulation of the muscle fiber microenvironment by activated satellite cells during hypertrophy. FASEB J 28: 1654–1665, 2014. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-239426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goh Q, Millay DP. Requirement of myomaker-mediated stem cell fusion for skeletal muscle hypertrophy. eLife 6: e20007, 2017. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iwata M, Englund DA, Wen Y, Dungan CM, Murach KA, Vechetti IJ Jr, Mobley CB, Peterson CA, McCarthy JJ. A novel tetracyclineresponsive transgenic mouse strain for skeletal muscle-specific gene expression. Skelet Muscle 8: 33, 2018. doi: 10.1186/s13395-018-0181-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8a.Kirby TJ, Patel RM, McClintock TS, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Peterson CA, McCarthy JJ. Myonuclear transcription is responsive to mechanical load and DNA content but uncoupled from cell size during hypertrophy. Mol Biol Cell 27: 788–798, 2016. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E15-08-0585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacLean HE, Chiu WS, Notini AJ, Axell AM, Davey RA, McManus JF, Ma C, Plant DR, Lynch GS, Zajac JD. Impaired skeletal muscle development and function in male, but not female, genomic androgen receptor knockout mice. FASEB J 22: 2676–2689, 2008. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-105726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarthy JJ, Mula J, Miyazaki M, Erfani R, Garrison K, Farooqui AB, Srikuea R, Lawson BA, Grimes B, Keller C, Van Zant G, Campbell KS, Esser KA, Dupont-Versteegden EE, Peterson CA. Effective fiber hypertrophy in satellite cell-depleted skeletal muscle. Development 138: 3657–3666, 2011. doi: 10.1242/dev.068858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moriya N, Miyazaki M. Akt1 deficiency diminishes skeletal muscle hypertrophy by reducing satellite cell proliferation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 314: R741–R751, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00336.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morton RW, Sato K, Gallaugher MP, Oikawa SY, McNicholas PD, Fujita S, Phillips SM. Muscle androgen receptor content but not systemic hormones is associated with resistance training-induced skeletal muscle hypertrophy in healthy, young men. Front Physiol 9: 1373, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murach KA, Englund DA, Dupont-Versteegden EE, McCarthy JJ, Peterson CA. Myonuclear domain flexibility challenges rigid assumptions on satellite cell contribution to skeletal muscle fiber hypertrophy. Front Physiol 9: 635, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murach KA, White SH, Wen Y, Ho A, Dupont-Versteegden EE, McCarthy JJ, Peterson CA. Differential requirement for satellite cells during overload-induced muscle hypertrophy in growing versus mature mice. Skelet Muscle 7: 14, 2017. doi: 10.1186/s13395-017-0132-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Murphy MM, Lawson JA, Mathew SJ, Hutcheson DA, Kardon G. Satellite cells, connective tissue fibroblasts and their interactions are crucial for muscle regeneration. Development 138: 3625–3637, 2011. doi: 10.1242/dev.064162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powers ML, Florini JR. A direct effect of testosterone on muscle cells in tissue culture. Endocrinology 97: 1043–1047, 1975. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-4-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Relaix F, Zammit PS. Satellite cells are essential for skeletal muscle regeneration: the cell on the edge returns centre stage. Development 139: 2845–2856, 2012. doi: 10.1242/dev.069088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossetti ML, Fukuda DH, Gordon BS. Androgens induce growth of the limb skeletal muscles in a rapamycin-insensitive manner. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 315: R721–R729, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00029.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rossetti ML, Steiner JL, Gordon BS. Androgen-mediated regulation of skeletal muscle protein balance. Mol Cell Endocrinol 447: 35–44, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seale P, Sabourin LA, Girgis-Gabardo A, Mansouri A, Gruss P, Rudnicki MA. Pax7 is required for the specification of myogenic satellite cells. Cell 102: 777–786, 2000. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00066-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sinha-Hikim I, Cornford M, Gaytan H, Lee ML, Bhasin S. Effects of testosterone supplementation on skeletal muscle fiber hypertrophy and satellite cells in community-dwelling older men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91: 3024–3033, 2006. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinha-Hikim I, Roth SM, Lee MI, Bhasin S. Testosterone-induced muscle hypertrophy is associated with an increase in satellite cell number in healthy, young men. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285: E197–E205, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00370.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sinha-Hikim I, Taylor WE, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF, Zheng W, Bhasin S. Androgen receptor in human skeletal muscle and cultured muscle satellite cells: up-regulation by androgen treatment. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89: 5245–5255, 2004. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wen Y, Murach KA, Vechetti IJ Jr, Fry CS, Vickery C, Peterson CA, McCarthy JJ, Campbell KS. MyoVision: software for automated high-content analysis of skeletal muscle immunohistochemistry. J Appl Physiol (1985) 124: 40–51, 2018. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00762.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Y, Zhao W, Zhao J, Pan J, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Bauman WA, Cardozo CP. Identification of androgen response elements in the insulin-like growth factor I upstream promoter. Endocrinology 148: 2984–2993, 2007. doi: 10.1210/en.2006-1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zeng F, Zhao H, Liao J. Androgen interacts with exercise through the mTOR pathway to induce skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Biol Sport 34: 313–321, 2017. doi: 10.5114/biolsport.2017.69818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]