Abstract

The recent discovery of cancer cell plasticity, i.e. their ability to reprogram into cancer stem cells (CSCs) either naturally or under chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, has changed, once again, the way we consider cancer treatment. If cancer stemness is a reversible epigenetic state rather than a genetic identity, opportunities will arise for therapeutic strategies that remodel epigenetic landscapes of CSCs. However, the systematic use of DNA methyltransferase and histone deacetylase inhibitors, alone or in combination, in advanced solid tumors including colorectal cancers, regardless of their molecular subtypes, does not seem to be the best strategy. In this review, we first summarize the knowledge researchers have gathered on the epigenetic signatures of CSCs with the difficulty of isolating rare populations of cells. We raise questions about the relevant use of currently available epigenetic inhibitors (epidrugs) while the expression of numerous cancer stem cell markers are often repressed by epigenetic mechanisms. These markers include the three cluster of differentiation CD133, CD44 and CD166 that have been extensively used for the isolation of colon CSCs.and . Finally, we describe current treatment strategies using epidrugs, and we hypothesize that, using correlation tools comparing associations of relevant CSC markers with chromatin modifier expression, we could identify better candidates for epienzyme targeting.

Keywords: Cancer stem cells, Colon cancer, Epigenetics, Chromatin modifying enzymes, CD44, CD133, CD166

Core tip: The recent discovery of cancer cell plasticity, i.e. their ability to reprogram into cancer stem cells either naturally or under chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, has changed, once again, the way we consider cancer treatment. In this review, we try to understand why current epigenetic treatments have failed to prove their efficacy in solid tumors including colorectal cancer and we hypothesize that, using correlation tools comparing associations of relevant cancer stem cell markers with chromatin modifier expression, we may identify better candidates for epienzyme targeting.

INTRODUCTION

Hierarchy of the tumor: turning an old concept into a new dogma

Although only recently upgraded as the keystone of the natural history of tumors, the concept of “cancer stem cells (CSCs)” was anticipated several decades ago as researchers soon discovered that cancer cells possessed unequal capacities when it comes to initiating a new tumor or resisting to therapies[1]. Indeed already during the 1960s, ethically disputed experiments of auto-transplantation that were conducted in human patients demonstrated that numerous cancer cells were necessary to establish cancer transplants, giving hints on the rare nature (1/1000000) of tumor-initiating cells[2].

With the arrival of the first commercially available cell sorters, followed by immunocompromised mouse models that allowed selective xenotransplantation of cancer cells, the interest in this cancer cell subpopulation has then been growing exponentially, with the field of hematologic malignancies as pioneers[1-3]. As early stem or progenitor cells were shown to be involved in leukemias and myelo-proliferative disorders, tumor initiating cells have rapidly been renamed “cancer stem cells”, hence creating a link with histological observations from the 1850’s when pathologists had first hypothesized that tumors could develop from residual embryonic tissues[1-3]. Indeed, CSCs share numerous characteristics with normal embryonic stem cells, such as rareness, cell cycle arrest and quiescence, unlimited self-renewal through asymmetric division, and addiction to stem cell signaling pathways.

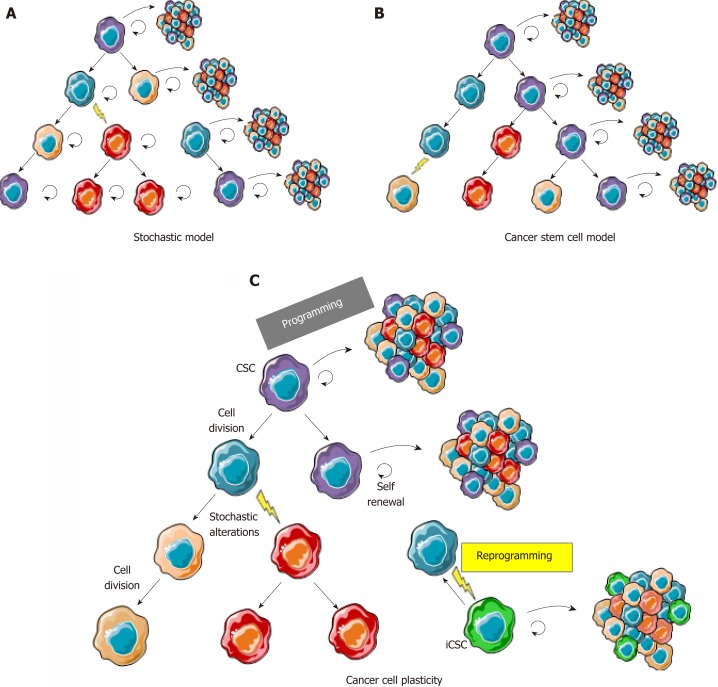

In solid tumors, the cancer stem cell (CSC) model (Figure 1B) was initially considered as a concept that could not be applied to all tumor types and was often opposed to the stochastic clonal evolution hypothesis[4,5], where genetic mutations are the major cause of tumor heterogeneity (Figure 1A)[6,7]. Increasing evidence of cancer plasticity, where cells easily exchange their position in the tumor hierarchy, switching from stem to non-stem states[8,9] and also from non-stem to stem states, reconcile these two models (Figure 1C). Indeed, several studies have demonstrated that cancer cells from different types of tumors, including colon cancer, can naturally convert to CSCs in culture, in total absence of therapeutic agents inducing genetic alteration[8]. Additionally, anti-cancer treatments such as chemotherapies[10] or radiotherapy[9] not only participate in the selection of resistant clones in the bulk of a tumor but also induce stemness characteristics in non-stem cancer cells. These findings are transposable to tumors from patients in whom stemness-related aggressiveness (invasion capacities, release of circulating tumor cells) is either innate or acquired after exposure to hypoxia, metabolic stress, and treatments.

Figure 1.

The cancer cell plasticity model reconciles cancer stem cell and stochastic models. A: In the stochastic model, cancer cells are heterogeneous because of accumulation of genetic and epigenetic alterations acquired through excessive proliferation, but most cells are able to proliferate and initiate new tumors; B: In the cancer stem cell model, cancer cells are organized in a hierarchy comparable to normal tissues where CSCs (in purple) are the only cells able to regenerate a tumor with its whole heterogeneity; C: In the cancer plasticity model, cancer cells are able to rapidly switch back and forth between a stem and a non-stem state. CSCs change to non-stem cell most likely occurs through epigenetic programming and silencing of cancer stem cell/pluripotency markers. Reprogramming, leading to induced CSCs (in green) from non-stem cancer cells, can either occur through reversible epigenetic modifications or genetic alterations, hence leading to a new clonal population of cancer cells in the tumor. CSC: Cancer stem cell; iCSC: Induced CSC.

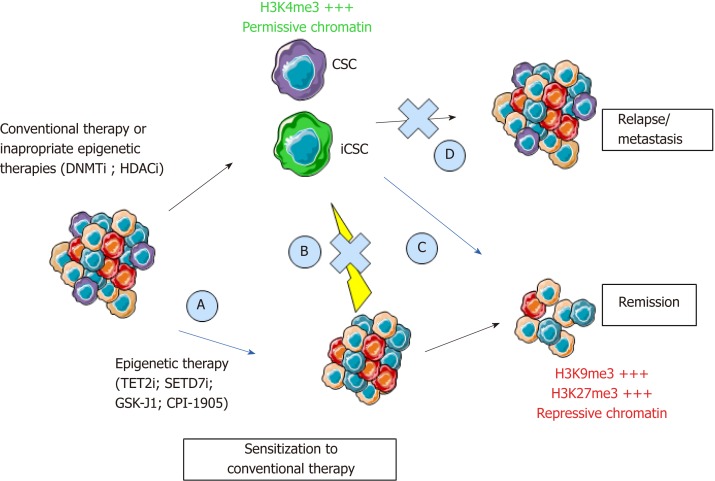

More importantly, the extreme cellular plasticity involving rapid phenotype switches between CSCs and their non-stem counterpart is probably mediated by epigenetic mechanisms that are reversible in nature, rather than newly acquired genetic mutations. Indeed, we (unpublished data) and others have shown a systematic equilibrium between CSC marker expressing and non-expressing cells that spontaneously occurs after cell sorting of negative vs positive populations[11]. In accordance with epigenetic mechanisms involved in this balance between stem and non-stem cancer cells, CSCs harbor a permissive epigenetic state[12-14], comparable to normal stem cells, while epigenetic profiles of differentiated cells are locked in order to shape cellular identity and functions. However, numerous genetic alterations may render cancer cell reprogramming more complicated to target. Understanding this flexibility is crucial for the development of new anticancer drugs. Therefore, new therapeutic strategies will have to combine the targeting of the bulk of the tumor and of the CSCs, whether they are pre-existing or induced. Hence, if these different types of CSCs share the same reversible reprogramming mechanisms, epigenetic therapies would represent an interesting strategy (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Epigenetic programming and reprogramming of cancer cells and consequences for therapeutic strategies. New therapeutics will have to combine the targeting of the bulk of the tumor, pre-existing CSCs, and iCSCs through inhibition of cancer cell reprogramming. Epigenetic therapies could inhibit CSCs to sensitize cancer cells to conventional therapies (A, C), inhibit cancer cells reprogramming (B), and inhibit relapse through inhibition of self-renewal (D). CSC: Cancer stem cell; iCSC: Induced CSCs; DNMTi: DNA methyltransferase inhibitor; HDACi: Histone deacetylase inhibitor; TET2i: Ten-eleven-translocation 2 inhibitor; SETD7i: SET domain containing 7 inhibitor; H3K4me3: Trimethylation of lysine 4 on histone 3; H3K9me3: Trimethylation of lysine 9 on Histone 3; H3K27me3: Trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone 3.

UNRAVELING THE EPIGENETIC SIGNATURE OF CSCs: A KEY TO UNDERSTANDING CANCER CELL PLASTICITY AND REPROGRAMMING

Current research on induced pluripotent stem cells teaches us that erasing epigenetic marks of the differentiated cell of origin greatly improves reprogramming[15,16]. Mapping stemness-associated chromatin modifications would surely facilitate the development of therapeutic strategies evoking differentiation of CSCs. Indeed, the “differentiating strategy” has proven its efficiency in certain types of hematologic tumors years ago[17]. On the other hand, these strategies have failed to prove their systematic efficacy in solid tumors, where CSCs may come from multiple origins, including normal differentiated cells[8,18], or stochastic genetic events altering cancer cells along tumor evolution.

Molecular mechanisms involved in the shaping of the cancer epigenetic landscapes, and especially in CSCs, are complex. Genetic alterations leading to loss or gain of epienzyme functions have been described[19], but only rare studies focus exclusively on CSCs. Furthermore, overexpression of epienzymes may not reflect an oncogenic role. The histone methyltransferase enhancer of zeste 2 (EZH2) is the perfect example of this paradox, while its overactivation in certain types of cancers is the sole sign of a compensation mechanisms in cells where histone H3 K27 trimethylation is diluted over excessive proliferation[20-22].

Because of the rareness and diversity of CSCs and the fact that no consensus has been found for markers that would allow their proper isolation, few studies have been able to define clearly the cancer stemness-associated epigenetic profiles. It has been shown, however, that mammary and hepatic CSCs harbor more permissive chromatin profiles, more prone to gene activation, than non-stem cancer cells[12]. They also harbor decreased DNA methylation and trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone H3 at tumor suppressor genes[12]. Similarly, trimethylation of lysine 4 on histone H3 is found preferentially at pluripotency genes such as BMI1, NOTCH1, and WNT1 in CSCs from acute myeloid leukemia patients[13]. CSCs from head and neck carcinomas harbor an epigenetic signature with only 22 differentially methylated genes between cluster of differentiation (CD)-44+ CSCs and CD44 non-stem cancer cell populations[14], pointing out subtle and specific differences between stem and non-stem cancer cells. The same type of signature has been identified in breast tumors[23], but still needs to be defined for CSCs from the different colon cancer molecular subtypes.

The common findings from studies on CSC epigenetic profiles are that CSC markers are either regulated by epigenetic mechanisms in normal and/or cancer cells or harbor different epigenetic profiles between stem and non-stem cancer cells[24]. Alternatively, CSC markers can themselves be directly or indirectly responsible for chromatin modifications through their presence in Polycomb Repressive Complexes (BMI1) or through histone demethylation (JARID1B).

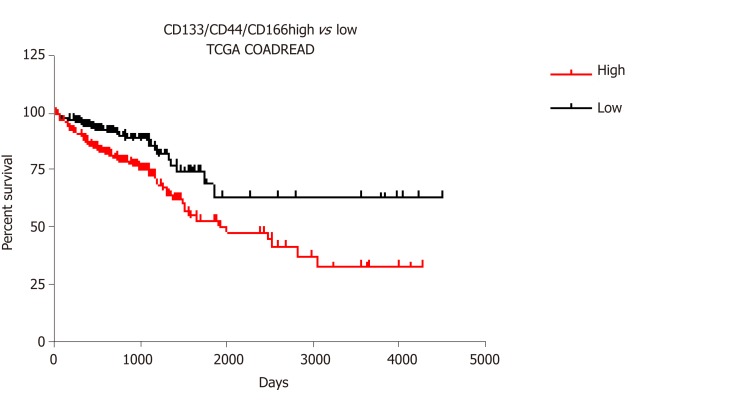

Among CSC markers, CD133 and CD44 have been extensively utilized to isolate cancer cells with tumorigenic characteristics in numerous types of cancers, including colon cancers in which CD133 predicts low survival. In combination with CD166, these two markers better stratify low, intermediate, and high-risk cases of colorectal cancer[25] (CRC) than the three markers alone. We have shown that combined expression of these three markers is associated with stemness and resistance to 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in colon cancer cells[26,27]. Interestingly, expression and splicing of these three markers are epigenetically regulated in cancer cells.

Epigenetic regulation of PROM1, encoding the CSC marker CD133

CD133 is a 120 kDa transmembrane glycoprotein that was initially identified in hematopoietic stem cells[28] and is involved in cell-cell interactions and membrane organization, through its binding to phospholipids[29]. CD133 is now used as a stem cell marker in most solid tumors including colorectal cancers[29]. More importantly, CD133 is directly involved in stemness properties as its inhibition alters self-renewal and tumorigenic capacities[30]. CD133 is also associated with metastasis and invasiveness through the decrease of metalloprotease 2 expression. Interestingly, its expression is positively correlated with the expression of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters ABCG1 and ABCG2, hence associating CSC properties to chemo-resistance through the presence of multidrug efflux pumps[28]. CD133 is correlated to poor prognosis in numerous cancers including CRC.

The human PROM1 gene, which encodes CD133 (prominin-1), consists of 28 exons and is localized on chromosome 4p15. The regulation of PROM1 transcription includes five alternative promoters (P1-5) involved in embryonic phase development. PROM1 harbors seven alternative spliced variants, of which the most documented are CD133s1 and CD133s2 (lacking exon 3)[31,32]. Of those only CD133s1 is mainly associated with normal tissue in brain, bone marrow, and blood[31]. CD133s2 expression is widely observed in human fetal tissue and adult tissues and in several cancers, including breast, colon, lung, and pancreatic carcinomas. CD133s2 is also associated with the human stem cell niche[33].

PROM1 expression is inversely correlated with methylation of CpG islands in its promoter in numerous cancer cell lines[34,35]. For example, in glioma tissues, an inverse correlation has been shown between the CpG methylation status of promoter P1 and P2 and expression levels of PROM1 transcripts. Epigenetic regulation of PROM1 also includes histone modifications, since synergistic effects are observed when using histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors in combination with DNA methyltransferase (DNMT) inhibitors to re-express the cell surface marker CD133 in ovarian cancer cells[24].

Epigenetic regulation of CD44

CD44 is a transmembrane glycoprotein interacting with components of the extracellular matrix including hyaluronic acid, collagens, fibronectins, integrins, and laminin[36]. These interactions induce cytoskeleton modifications and activation of signaling pathways involved in cell adhesion and migration. CD44 expression has been associated with tumor progression, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition[37], and poor survival in colon cancers[38]. Mutations have been described in solid tumors, suggesting its implication in carcinogenesis[37]. Most importantly, CD44-variant-6 (v6) is a well-recognized marker of colon and gastric CSCs[39,40].

The human CD44 gene consists of 20 exons and is located on chromosome 11p13. Exons 1-5 and 15-19 encode homologous N-ter (extracellular) and C-ter (extracellular, transmembrane and intracellular) domains respectively forming the standard isoform CD44s. Alternative splicing of exons 5a-14 result in different variants/isoforms of CD44 (CD44v). CD44 variants are overexpressed in numerous types of solid tumors including pancreatic (CD44v2-6), breast (CD44v6/v8-10), prostate (CD44v2/v6), head and neck (CD44v3), and colon (CD44v6/v10) cancers[37]. In contrast with CD44s variant that is absent from mouse normal intestinal stem cells[37], CD44 variants (CD44v4-10) have been associated with normal and cancer stemness. For instance, CD44v6 and CD44v4 are largely overexpressed in stem cells compared to their progeny (transit-amplifying cells). CD44 variants, and not CD44s, are involved in adenoma formation in mouse models of familial polycystic adenomas[41]. Similarly, expression of CD44v6 is restricted to colon CSCs and is associated with worse survival in patients with CRC[39]. In most studies, CD44v4-10 variants are associated with aggressiveness, resistance, metastasis, and poor prognosis in solid tumors including colon cancers.

Epigenetic regulation of the CD44 gene has recently been described. DNA methylation at CpG islands located in the promoter and histone H3 acetylation regulate its silencing or expression[37], respectively. DNMT inhibition induced DNA methylation and histone modification changes at the CD44 gene promoter, increasing CD44 mRNA levels in cancer cell lines[37,42]. More importantly, alternative splicing of CD44 and, hence, the expression of CSC specific variants is epigenetically regulated. Indeed, accumulation of histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation and HP1 stabilizes pre-mRNA binding to the chromatin and therefore facilitates exon inclusion[43].

Epigenetic regulation of ALCAM encoding the CSC marker CD166

CD166 is a member of the immunoglobulin superfamily and is engaged in homophilic or heterophilic interactions with the cell surface receptor CD6. CD166, which is expressed on antigen-presenting cells, is involved in maturation of CD6-expressing resting T-cells and is also expressed in mesenchymal stem cells, neural cells, osteoblasts, and stromal cells of the bone marrow. It is involved in hematopoiesis, development of central and peripheral nervous system, sense organs, and differentiation of endothelial as well as epithelial lineages[44]. CD166 has proven its relevance as a CSC marker alone or in combination with CD44 in several studies including studies on colon cancer cell lines[45,46].

The human gene ALCAM, encoding CD166, is located on chromosome 3q.13 and consists of 16 exons. A soluble isoform, produced through alternative splicing, has been described, but its role remains unknown[47].

The ALCAM promoter harbors several CpG islands regulated by DNA methylation. It has been shown that the DNMT inhibitor 5-Aza-2’-deoxycytidine increased its expression in breast cancer cells[48], hence raising questions about the use of these inhibitors in breast cancer patients.

Interestingly, the three discussed CSC and survival markers (CD44, CD166, and CD133, Figure 3) are not only epigenetically regulated in cancer cells, but our transcriptomic analyses of public CRC data also revealed that the combined expression of these markers in colon cancer is correlated with a specific panel of epienzyme expression (both positive and negative correlations are listed in Tables 1-6).

Figure 3.

Survival analysis for CD133/CD44/CD166 expression profiles in colorectal cancer. The association of CD133/CD44/CD166 transcript expression with cancer survival in the COADREAD Cancer Genome Atlas dataset was analyzed using the SurvExpress portal[62]. Kaplan-Meier plot and Cox survival statistics were established with maximized risk group assessment (466 patients with 255 in low vs 211 in high risk profile). The log rank for equal curves indicated a significant difference (P value = 0.0007) with a hazard ratio of 2.12 (95%CI: 1.35-3.31, P value = 0.0009).

Table 1.

Negative correlation between combined expression of cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD44 and CD166 and epigenetic writers

| Family/gene symbol | Epidrug/chemical probe | Clinical trials for CRC | Results/status | Z-score | P value |

| DNA methyltransferases | 5-azacytidine (Vidaza)1 | Early Phase I to phase II[63,64] | No OR[63,65] | ||

| 5-aza-2’-désoxycytidine (Decitabine)1 | Phase I to phase II[66-68] | No OR[66]; beneficial with Panitumumab[68] | |||

| EGCG (Green tea extract) | Preclinical spheroid-derived cancer stem cell xenograft models[69] | Sensitization to chemotherapy | |||

| Zebularine | Preclinical xenografts[70] | Anticancer activity | |||

| RG108, Procainamide2 | |||||

| DNMT3A, DNMT3B, DNMT3L | -2.788/-4.848/-4.321 | < 0.005 | |||

| Activating Lysine methyltransferases | |||||

| SETD6 | vp22-RelA302-3163[71] | -4.641 | 3.47E-06 | ||

| SETD1A | -4.375 | 1.212E-05 | |||

| Repressive Lysine methyltransferases | |||||

| SMYD5 | - | -4.514 | 6.371E-06 | ||

| EHMT2 | UNC02243, UNC06423, BIX-012943 | -4.322 | 1.545E-05 | ||

| SETDB2 | - | -3.6 | 0.0003176 | ||

| PRDM13 | - | -3.442 | < 0.005 | ||

| SUV39H1, SUV39H2 | Chaetocin3 | -3.422/-2.934 | 0.0006216 | ||

| PRDM12 | - | -3.089 | 0.00201 | ||

| EZH1 | UNC19993 | -2.787 | 0.005314 | ||

| EZH2 | CPI-12052,4, EPZ-6438 (Tazemetostat)2, DZNep2, UNC19993 | -2.495 | 0.01259 | ||

| Arginine methyltransferases | |||||

| CARM1 | MS0493, SGC20853, TP-0643[72] | -3.812 | 0.0001381 | ||

| PRMT1 | MS0233[72] | -3.659 | 0.0002534 | ||

| PRMT6 | MS0233, MS049c, EPZ0204113[72], 6′-methyleneamine sinefungin3[73] | -3.521 | 0.0004301 | ||

| Histone acetylation | |||||

| KAT2A | CPTH23[74], γ-butyrolactone3 (MB-3)[75] | -4.683 | 2.823E-06 | ||

| NAA10, NAA16, NAA20, NAA38, NAA40 | - | -4.335/-3.255/-3.786/-3.801/-2.665 | < 0.01 | ||

| NAT8, NAT9 | - | -2.573/-3.995 | < 0.01 | ||

| NCOA5, NCOA6 | - | -3.238/-3.112 | < 0.002 | ||

| Histone phosphorylation | |||||

| BAZ1B | - | -2.374 | 0.01758 | ||

| Histone glycosylation | |||||

| OGT | - | -3.172 | 0.001512 | ||

Approved for the treatment of other diseases;

Used in clinical trials for other diseases;

Not yet used in clinical trials;

Activator. CRC: Colorectal cancer; OR: Objective response.

EPIENZYME CORRELATION WITH COLON CSC MARKERS: A HINT FOR SUCCESS IN EPIGENETIC THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES?

Current epigenetic strategies

Most solid tumors, including CRC, acquire chemoresistance over time. In addition to expected chemo-induced genetic alterations, the molecular mechanisms involved include transcriptional plasticity that is regulated epigenetically, for example by multiple DNA methylation changes at CpG islands[49]. Contrary to genetic alterations, epigenetic modifications are potentially reversible, paving the way for novel cancer therapies.

This past decade has seen the emergence of many epigenetic therapies, especially DNA hypomethylating drugs (DNA methyltransferase inhibitors) and HDAC inhibitors (HDACi), as well as lysine-specific histone demethylase-1, EZH2 inhibitors, and many others[50].

Epigenetic drugs have shown beneficial effects for the treatment of hematological malignancies and led to the approval of epidrugs like 5-azacitidine, decitabine, vorinostat, romidepsin, belinostat, and panobinostat for patient treatment[50]. In contrast, clinical trials assessing the efficacy of these epigenetic drugs in monotherapies for CRC and other solid tumors failed to improve clinical outcomes with, in some cases, no response at all[51], never passing the phase III trial necessary for approval (clinical trials for CRC listed in Tables 1-6).

Several hypotheses could be raised regarding this apparent lack of efficacy of epidrugs for solid tumors. First, compared to hematologic malignancies, solid tumors harbor a weaker penetrance of mutations in genes encoding chromatin modifying enzymes[19]. Second, the pleiotropic effect of current epidrugs leads to the combined inhibition of many members of a given family of epienzymes that have a broad spectrum of action and opposing roles in cancer cells. Third, and most importantly, cancer cell plasticity, and the switch between stem and non-stem state, is orchestrated by complex mechanisms, including epigenetic silencing of CSC markers and pluripotency genes. Despite genetic heterogeneity among cancer cells[52] (due to stochastic or chemo-/radio-induced mutations along tumor evolution/treatment), DNA methylation and histone deacetylation seem to represent typical mechanisms involved in repressing stemness markers in non-stem cancer cells, as previously demonstrated for CD44, CD133, and CD166. Therefore, inhibiting DNMT and HDAC may result in increased expression of CSC markers[37,42,48] along with an increased stemness potential. Last, patients included in these clinical trials often present metastatic or advanced disease and are recruited regardless of the molecular subtype of cancer. As aberrant DNA methylation is an early step of carcinogenesis, advanced disease may not be the relevant stage for treatments with DNMTi and HDACi.

To refine these treatment strategies, tumor grade, heterogeneity, and subtypes of cancers will have to be considered. Indeed, determining which tumors will benefit from epigenetic differentiation strategies[53] and which tumors would acquire stemness capacities after epigenetic resetting is mandatory. Hence, modulating epigenetic alterations to sensitize cancer cells to other conventional therapies[54] or to lower their aggressiveness seems to be a reasonable goal when it comes to epigenetic strategies for advanced disease, as shown by numerous studies on cancer cell lines[53]. HDAC and DNMT inhibitors, used alone or in combination, are able to sensitize resistant cancer cells and their use after conventional or targeted therapies have proven their efficacy in clinical trials[55]. For instance, treatment with 5-azacitidine or 5-Aza-2’-deoxycitidine increases sensitivity of colon cancer cells to irinotecan and 5-FU[56]. Irinotecan sensitivity with DNMTi was confirmed in in vivo CRC models showing tumor regression and increased survival in contrast with monotherapies. The same results were observed with the combination of 5-azacitidine and a BRAF inhibitor in CRC xenograft models[57]. Synergetic therapies were also observed with HDACi in combination with 5-FU. Indeed, trichostatine A in combination with 5-FU suppresses colon cancer cell viability[58]. However, initiating re-differentiation in CSCs remains a challenge dependent on the characteristics of each tumor type and with their specific genetic alterations.

Molecular subtypes of CRC or chemoresistance also predict how and whether or not patients will benefit from existing epidrug treatments. For instance, it has been shown that treatment with 5-azacitidine can restore chemosensitivity to irinotecan in microsatellite stable CRC cell lines but not in microsatellite instable CRC cell lines[56]. Moreover, microsatellite instability CRC status is associated with the hypermethylation of glutathione peroxidase 3, a gene encoding an antioxidant selenoprotein involved in drug metabolism. In this case, treatment with 5-azacitidine induced an increase of glutathione peroxidase 3 expression and a decrease of chemosensitivity to oxaliplatin in microsatellite instability CRC cell lines[59]. These findings emphasize the need for personalized therapies that consider CRC interindividual heterogeneity and classification.

Exploring new avenues for colon cancer treatment

In order to better anticipate how colon CSCs will respond to the different existing therapies, we analyzed TCGA_COADREAD data of 379 colon cancer patients using LinkedOmics[60]. With this meta-analysis we assessed the correlation Z-score estimate (Stouffer method-based) and a P value between the combined expression of the three colon CSC markers CD133, CD44, and CD166 and an exhaustive list of known chromatin modifying enzymes (epigenetic writers and erasers) and chromatin binding proteins (epigenetic readers). The observed negative and positive correlation of expression between the three CSC markers and a significant number of epienzymes are highlighted in Tables 1 to 6.

Strikingly, DNMT3A, DNMT3B, and DNMT3L, the DNA methyltransferases that are responsible for de novo DNA methylation, showed a negative correlation score with the combined expression of the three CSC markers studied (Table 1), while the expression of DNMT1, responsible for DNA methylation maintenance, was not significantly correlated with the combination of these markers (-2 < score < 2). Similarly, three class I and II HDAC as well as two sirtuins were found negatively correlated to the combination of markers (Table 2). None of the known HDAC were found positively correlated with the expression of the three CSC markers. This strongly suggests that inhibiting DNMT or HDAC activity would have no effect in colon cancers overexpressing CSC markers (and potentially harbor high stemness properties) but may have adverse effect in low-expressing and maybe less aggressive colon cancers. These data are in accordance with disappointing clinical trials that have been conducted so far with these inhibitors in colon cancer patients. Interestingly, our analyses suggest that another strategy to regulate DNA methylation in colon CSCs may be the inhibition of the methylcytosine dioxygenase TET2, known to trigger DNA demethylation and found correlated to CSC marker expression in our analyses (Table 3).

Table 2.

Negative correlation between combined expression of cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD44 and CD166 and epigenetic erasers

| Family/gene symbol | Epidrug/chemical probe | Clinical trials for CRC | Results | Z-score | P value |

| Histone deacetylation (Zinc-dependent) | |||||

| Acide valproïque1 | I to II | In combination: OR in 64% patients or SD[76,77] | |||

| Belinostat2, Apicidin3 | |||||

| Entinostat | I to I/II | No OR[78] or SD[79] | |||

| Panobinostat | I | PR and SD in combination with Bevacizumab[80] | |||

| Vorinostat (SAHA) | I to II | No OR[81,82]; SD and PR with Bortezomib or 5FU and leucovorin or Doxorubicin[83-85] | |||

| Trichostatine A2 | |||||

| Mocetinostat2 | |||||

| Sodium phenylbutyrate2 | I | In combination with 5-FU: SD[86] | |||

| Class I | Romidepsin (Istodax)1 | II | Ineffective[86] | ||

| CI-994 | I | PR in combination with carboplatin and placlitaxel[87] | |||

| HDAC8 | TM-2-514, CUDC-1012, Pracinostat2, Ricolinostat2, Citarinostat2, Abexinostat2, Quisinostat3, PCI-340513 | -2.527 | 0.0115 | ||

| Class IIa (1 catalytic site, mainly cytoplasmic) | |||||

| HDAC5 | CUDC-1012, Pracinostat2, Domatinostat2, Quisinostat3, LMK-2353, TMP1953, TMP2693 | -4.133 | 3.581E-05 | ||

| Class IIb (2 catalytic sites, mainly cytoplasmic) | |||||

| HDAC10 | CUDC-1012, CUDC-9072, Pracinostat2, Domatinostat2, Abexinostat2, Tucidinostat2, Quisinostat3 | -3.17 | 0.001525 | ||

| Histone deacetylation NAD+ dependent (Class III) | |||||

| Resveratrol4 | I | Reduced cell proliferation[88] | |||

| Salermide3[89] | |||||

| SIRT6 | OSS_1281673 | -3.467 | 0.0005257 | ||

| SIRT7 | -2.582 | 0.009835 | |||

| Histone demethylation | |||||

| LSD family of demethylases | |||||

| ORY-10013, (±)-tranylcypromine3 | |||||

| KDM2B | - | -3.54 | 0.0004003 | ||

| KDM4D | - | -2.704 | 0.006848 | ||

| JmjC containing lysine demethylases | |||||

| JIB-043 | |||||

| JMJD6 | IOX13 | -2.59 | 0.00961 | ||

| JMJD5 | IOX13 | -2.588 | 0.009654 | ||

Approved for the treatment of other diseases;

Used in clinical trials for other diseases;

Not yet used in clinical trials;

Activator. CRC: Colorectal cancer; OR: Objective response; SD: Stable disease; PR: Partial response.

Table 3.

Positive correlation between combined expression of cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD44 and CD166 and epigenetic erasers

| Family/gene symbol | Putative epidrug/chemical probe | Z-score | P value |

| DNA demethylation | |||

| TET2 | - | 5.968 | 2.40E-09 |

| Histone demethylation | |||

| LSD family of demethylases | |||

| ORY-10013, (±)-tranylcypromine3 | |||

| KDM3B | 5.636 | 1.74E-08 | |

| KDM4B | CP23[90] | 5.212 | 1.87E-07 |

| KDM4C | CP23[90] | 3.895 | 9.81E-05 |

| KDM5B | CPI-4553, AS-83513, 593 (KDOAMA-253)[90] | 9.092 | 9.72E-20 |

| KDM6A | GSK-J13 | 2.84 | 0.00451 |

| KDM6B | GSK-J13 | 4.014 | 5.98E-05 |

1Approved for the treatment of other diseases; 2Used in clinical trials for other diseases;

Not yet used in clinical trials.

The correlation scores we obtained for other chromatin writers, readers, and erasers seem more specific to the enzyme itself than to their role in the shaping of epigenetic landscapes (Tables 1-6).

We found a negative correlation between the expression of the three markers and several histone lysine methyltransferases associated with the establishment of constitutive or facultative heterochromatin, including EZH2 that has recently emerged as one of the new favorite targets for epigenetic therapies[20] (Table 1). These estimated scores in colon cancer expressing CD133, CD44, and CD166 suggest that an activator of EZH2, such as CPI-1205, may have better efficacy than known inhibitors in clinical trials to influence cancer stemness and are in accordance with a protective role of EZH2 in cell differentiation. Similarly, expression of EHMT2 (also known as G9A and KMT1C), encoding another lysine methyltransferase that also recently raised interests in the epidrug field, was inversely correlated with the three CSC markers expression (Table 1).

Only few lysine methyltransferases associated with gene activation were found correlated or inversely correlated with the combined expression of the three markers. Among them, SETD7 (Table 4), but not SETD6 (Table 1), may be a good candidate to inhibit stemness in colon cancer cells.

Table 4.

Positive correlation between combined expression of cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD44 and CD166 and epigenetic writers

| Family/gene symbol | Epidrug/chemical probe | Clinical trials for CRC | Results/status | Z-score | P value |

| Histone acetyltransferases | |||||

| EP300 | Curcumin | Early phase I to III | Low bioavailability[91] | 2.513 | 0.01198 |

| Garcinol3, C6463 | |||||

| NCOA1 | Bufalin2[92] | 5.45 | 5.04E-08 | ||

| NCOA4 | - | 4.183 | 2.88E-05 | ||

| NCOA7 | - | 5.788 | 7.14E-09 | ||

| KAT2B | Ischemin3[93] | 6.514 | 7.31E-11 | ||

| Activating Lysine methyltransferases | |||||

| ASH1L | - | 2.591 | 0.009565 | ||

| SMYD1 | - | 2.739 | 0.00616 | ||

| SETD7 | PFI-23 | 5.11 | 3.23E-07 | ||

| Repressing Lysine methyltransferases | |||||

| PRDM8 | - | 3.411 | 0.0006465 | ||

| Putative Lysine methyltransferase | |||||

| PRDM10 | - | 2.448 | 0.01438 | ||

| Arginine methyltransferases | |||||

| PRDM1 | - | 2.874 | 0.004056 | ||

| PRMT2 | - | 2.901 | 0.003726 | ||

| Histone ubiquitination | |||||

| UBE2B | - | 2.748 | 0.005991 | ||

| UBE2H | - | 5.809 | 6.30E-09 | ||

| Histone phosphorylation | |||||

| JAK1 | Ruxolitinib | Phase I and II | No benefit over Regorafenib alone[94] | 7.739 | 1.01E-14 |

| Baricitinib2, Momelotinib2, Filgotinib2, Decernotinib2, Cerdulatinib2, Solcitinib2, Oclacitinib maleate2 | |||||

| JAK2 | Ruxolitinib | Phase I and II | No benefit over Regorafenib alone[94] | 6.7 | 2.09E-11 |

| Gandotinib2, AZD14802, BMS-9115432, AT92832, XL0192, Baricitinib2, Momelotinib2, Filgotinib2, Decernotinib2, Cerdulatinib2, JAK2/HDAC Dual Inhibitors3[95] | |||||

| Histone biotinylation | |||||

| BTD | Biotinyl-methyl 4-(amidomethyl)benzoate3[96] | 4.379 | 1.19E-05 | ||

1Approved for the treatment of other diseases;

Used in clinical trials for other diseases;

Not yet used in clinical trials. CRC: Colorectal cancer.

Recently, small molecules that can target specific bromodomains have been extensively developed[61]. Bromodomains are part of a family of epigenetic readers that play pivotal roles in transcriptional regulation through the binding of acetylated histones and the recruitment of other epienzymes in epigenetic complexes at specific sites. We found only a few bromodomain-containing proteins whose expression was positively (BPTF, BAZ2B, Table 5) or negatively (BRD7, Table 6) correlated to the combined expression of the three CSC markers.

Table 5.

Positive correlation between combined expression of cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD44 and CD166 and epigenetic readers

| Family/gene symbol | Epidrug/chemical probe | Z-score | P value |

| Methylated DNA binding | |||

| MBD1 | - | 2.593 | 0.009517 |

| MBD2 | - | 3.477 | 0.0005076 |

| ZBTB4 | - | 5.496 | 3.89E-08 |

| Methylated histone binders | |||

| Zinc finger, PHD-type | |||

| DPF3 | 3.503 | 0.0004602 | |

| Bromodomain | Apabetalone2, Bromosporine3 | ||

| BPTF | 2.621 | 0.008773 | |

| BAZ2B | GSK28013 | 4.791 | 1.66E-06 |

| Tudor domain | |||

| TDRD1 | - | 2.459 | 0.01394 |

| TP53BP1 | - | 2.965 | 0.003029 |

| Other cofactors of epigenetic complexes | |||

| RBBP5 | - | 2.966 | 0.003014 |

| TADA2B | - | 3.382 | 0.0007189 |

| ELP2 | PLX-47203 | 3.277 | 0.00105 |

| ELP3 | - | 2.622 | 0.00875 |

| TAB2 | - | 2.551 | 0.01074 |

| NCOR1 | - | 3.62 | 0.0002949 |

| Chromodomain (Chromatin Organization Modifier Domain) | |||

| CHD1, CHD3, CHD9 | - | 3.007/4.099/4.367 | < 0.003 |

1Approved for the treatment of other diseases;

Used in clinical trials for other diseases;

Not yet used in clinical trials.

Table 6.

Negative correlation between combined expression of cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD44 and CD166 and epigenetic readers

| Family/gene symbol | Putative epidrug/chemical probe | Z-score | P value |

| Methylated DNA binding | |||

| MBD3 | - | -3.601 | 0.0003174 |

| ZBTB38 (Kaiso family) | - | -2.557 | 0.01055 |

| Histone binders | |||

| Bromodomains | |||

| BRD7 | BI72733, BI-95643, TP-4723[97] | -4.906 | 9.301E-07 |

| Zinc finger, Plant Homeodomain (PHD)-type | |||

| ING1, ING5 | - | -2.544/-4.255 | < 0.05 |

| PHF20 | - | -3.094 | 0.001973 |

| PHF14 | - | -2.934 | 0.003344 |

| PHF5A | - | -2.521 | 0.01171 |

| DPF1 | - | -2.78 | 0.00543 |

| Tudor domain | |||

| TDRKH | - | -2.755 | 0.005875 |

| WD40 motif | |||

| EED | A-3953[98] | -4.307 | 1.652E-05 |

| Other cofactors of epigenetic complexes | |||

| DPY30 | - | -3.549 | 0.0003863 |

| WDR5 | OICR-94293 | -3.31 | 0.0009321 |

| TADA2A | -2.473 | 0.01341 | |

1Approved for the treatment of other diseases; 2Used in clinical trials for other diseases;

Not yet used in clinical trials.

Among epigenetic readers, methylated DNA binding proteins have probably been overlooked as epidrug targets since expression of both MBD1 and MBD2 is positively correlated with CSC markers (Table 5).

Targeting members of the lysine-specific histone demethylase family of histone demethylases using inhibitors such as GSK-J1 may also be a good option since only a few of them are inversely correlated with the three CSC markers while KDM3B, KDM4B/C, KDM5B, KDM6A (UTX), and KDM6B (JMJD3) are positively correlated to their expression (Table 3).

Finally, JAK1/2 kinases, which possess a histone phosphorylation activity and are the targets of numerous inhibitors already tested in the clinic, mainly for other diseases, should probably be reconsidered for colon cancer patients with high expression of CD133, CD44, and CD166 or after conventional therapies. Indeed, our meta-analyses suggest that their expression is positively correlated to the expression of the three CSC markers (Table 4).

As mentioned above, CD44, CD133, and CD166 are potent markers of CSCs from multiple tissues including digestive (gastric, pancreatic) and non-digestive cancers in which they are epigenetically regulated. Therefore, these considerations could be largely applicable to other types of cancers, in which correlation studies between epienzymes and CSC markers may be of great interest.

PERSPECTIVES

Although epigenetic therapies are conceptually very promising, several pitfalls will have to be overcome in order to take a step forward in clinical trials for solid tumors. First, while intra-tumor and inter-individual heterogeneity of CRC is now evident, epigenetic landscapes and epienzyme activity will have to be studied in all types of tumor cells. Single cell approaches will be very useful to circumvent the difficulty of exploring rare CSCs from different CRC consensus molecular subtypes. Second, studies to prove causal correlations between epienzyme expression and the control of stemness will be mandatory in order to clear up confusion relative to the oncogenic or tumor suppressive roles of chromatin modifiers. Finally, the major difficulty for the design of new epidrugs is to target efficiently a single member of entire families of epienzymes that have homologous domains but different roles in stemness. To circumvent this difficulty, increasing specificity by targeting epigenetic complexes and therefore epienzyme-epienzyme interactions may be a better option for new designs. Based on these considerations, epigenetic personalized medicine will be truly envisioned.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr Samuel Malone for his careful and critical reading of the manuscript, for the helpful comments and for English editing.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare no conflicts of interests for this article.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: March 28, 2019

First decision: June 3, 2019

Article in press: September 11, 2019

Specialty type: Cell and tissue engineering

Country of origin: France

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): A, A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Chivu-Economescu M, Kiselev SL, Miyoshi E S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Xing YX

Contributor Information

Audrey Vincent, Lille University, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, CHU Lille, UMR-S 1172-Jean-Pierre Aubert Research Center, Lille F-59000, France.

Aïcha Ouelkdite-Oumouchal, Lille University, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, CHU Lille, UMR-S 1172-Jean-Pierre Aubert Research Center, Lille F-59000, France.

Mouloud Souidi, Lille University, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, CHU Lille, UMR-S 1172-Jean-Pierre Aubert Research Center, Lille F-59000, France.

Julie Leclerc, Lille University, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, CHU Lille, UMR-S 1172-Jean-Pierre Aubert Research Center, Lille F-59000, France; Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Lille University Hospital, Lille F-59000, France.

Bernadette Neve, Lille University, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, CHU Lille, UMR-S 1172-Jean-Pierre Aubert Research Center, Lille F-59000, France.

Isabelle Van Seuningen, Lille University, Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale, CHU Lille, UMR-S 1172-Jean-Pierre Aubert Research Center, Lille F-59000, France. isabelle.vanseuningen@inserm.fr.

References

- 1.D'Andrea V, Guarino S, Di Matteo FM, Maugeri Saccà M, De Maria R. Cancer stem cells in surgery. G Chir. 2014;35:257–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Southam CM, Brunschwig A. Quantitative studies of autotransplantation of human cancer. Cancer. 1961;14:971–978. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huntly BJ, Gilliland DG. Leukaemia stem cells and the evolution of cancer-stem-cell research. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:311–321. doi: 10.1038/nrc1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and CSCs. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shackleton M, Quintana E, Fearon ER, Morrison SJ. Heterogeneity in cancer: cancer stem cells versus clonal evolution. Cell. 2009;138:822–829. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basicević V, Kleut-Jelić R, Orovcanec M, Vuković D. [Frequency and significance of lambliasis in the clinical material] Med Pregl. 1972;25:323–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turajlic S, McGranahan N, Swanton C. Inferring mutational timing and reconstructing tumour evolutionary histories. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2015;1855:264–275. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frohman LA, Downs TR, Williams TC, Heimer EP, Pan YC, Felix AM. Rapid enzymatic degradation of growth hormone-releasing hormone by plasma in vitro and in vivo to a biologically inactive product cleaved at the NH2 terminus. J Clin Invest. 1986;78:906–913. doi: 10.1172/JCI112679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bardají JL, Villarroel MT, Vázquez de Prada JA, Ruano J, Olalla JJ, Martín Durán R, Martín Lorente JL, López Morante A. [Acute pericarditis and cardiac tamponade as the initial manifestation of ulcerative colitis] Rev Esp Cardiol. 1988;41:257–260. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freitas DP, Teixeira CA, Santos-Silva F, Vasconcelos MH, Almeida GM. Therapy-induced enrichment of putative lung cancer stem-like cells. Int J Cancer. 2014;134:1270–1278. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sugiura T, Iwasaka T, Takayama Y, Takahashi N, Matsutani M, Inada M. The factors associated with fascicular block in acute anteroseptal infarction. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:529–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yasuda H, Soejima K, Watanabe H, Kawada I, Nakachi I, Yoda S, Nakayama S, Satomi R, Ikemura S, Terai H, Sato T, Suzuki S, Matsuzaki Y, Naoki K, Ishizaka A. Distinct epigenetic regulation of tumor suppressor genes in putative cancer stem cells of solid tumors. Int J Oncol. 2010;37:1537–1546. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamazaki J, Estecio MR, Jelinek J, Graber D, Lu Y, Ramagli L, Liang S, Kornblau SM, Issa JP. 2010. Genome-wide epigenetic analysis of CSCs in acute myeloid leukemia. ASH Annual Meeting; 2010. American Society of Hematology. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furusawa J, Zhang H, Vural E, Stone A, Fukuda S, Oridate N, Fang H, Ye Y, Suen JY, Fan CY. Distinct epigenetic profiling in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma stem cells. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144:900–909. doi: 10.1177/0194599811398786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bar-Nur O, Russ HA, Efrat S, Benvenisty N. Epigenetic memory and preferential lineage-specific differentiation in induced pluripotent stem cells derived from human pancreatic islet beta cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2011;9:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.el-Fiky SM, Kolkaila AM, Dawd DS, Wahab RM. Histochemical aspects of hydatidiform mole and choriocarcinoma. Acta Histochem. 1973;47:115–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cimino G, Lo-Coco F, Fenu S, Travaglini L, Finolezzi E, Mancini M, Nanni M, Careddu A, Fazi F, Padula F, Fiorini R, Spiriti MA, Petti MC, Venditti A, Amadori S, Mandelli F, Pelicci PG, Nervi C. Sequential valproic acid/all-trans retinoic acid treatment reprograms differentiation in refractory and high-risk acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8903–8911. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vincent A, Van Seuningen I. On the epigenetic origin of cancer stem cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1826:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Timp W, Feinberg AP. Cancer as a dysregulated epigenome allowing cellular growth advantage at the expense of the host. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:497–510. doi: 10.1038/nrc3486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim KH, Roberts CW. Targeting ezh2 in cancer. Nat Med. 2016;22:128–134. doi: 10.1038/nm.4036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Vlerken LE, Kiefer CM, Morehouse C, Li Y, Groves C, Wilson SD, Yao Y, Hollingsworth RE, Hurt EM. EZH2 is required for breast and pancreatic cancer stem cell maintenance and can be used as a functional cancer stem cell reporter. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2013;2:43–52. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan J, Yang X, Jiang X, Zhou J, Li Z, Lee PL, Li B, Robson P, Yu Q. Integrative epigenome analysis identifies a Polycomb-targeted differentiation program as a tumor-suppressor event epigenetically inactivated in colorectal cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1324. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun JG, Liao RX, Qiu J, Jin JY, Wang XX, Duan YZ, Chen FL, Hao P, Xie QC, Wang ZX, Li DZ, Chen ZT, Zhang SX. Microarray-based analysis of microRNA expression in breast cancer stem cells. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2010;29:174. doi: 10.1186/1756-9966-29-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baba T, Convery PA, Matsumura N, Whitaker RS, Kondoh E, Perry T, Huang Z, Bentley RC, Mori S, Fujii S, Marks JR, Berchuck A, Murphy SK. Epigenetic regulation of CD133 and tumorigenicity of CD133+ ovarian cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:209–218. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horst D, Kriegl L, Engel J, Kirchner T, Jung A. Prognostic significance of the cancer stem cell markers CD133, CD44, and CD166 in colorectal cancer. Cancer Invest. 2009;27:844–850. doi: 10.1080/07357900902744502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corvaisier M, Bauzone M, Corfiotti F, Renaud F, El Amrani M, Monté D, Truant S, Leteurtre E, Formstecher P, Van Seuningen I, Gespach C, Huet G. Regulation of cellular quiescence by YAP/TAZ and Cyclin E1 in colon cancer cells: Implication in chemoresistance and cancer relapse. Oncotarget. 2016;7:56699–56712. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Touil Y, Igoudjil W, Corvaisier M, Dessein AF, Vandomme J, Monté D, Stechly L, Skrypek N, Langlois C, Grard G, Millet G, Leteurtre E, Dumont P, Truant S, Pruvot FR, Hebbar M, Fan F, Ellis LM, Formstecher P, Van Seuningen I, Gespach C, Polakowska R, Huet G. Colon cancer cells escape 5FU chemotherapy-induced cell death by entering stemness and quiescence associated with the c-Yes/YAP axis. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:837–846. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jang JW, Song Y, Kim SH, Kim J, Seo HR. Potential mechanisms of CD133 in cancer stem cells. Life Sci. 2017;184:25–29. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ren F, Sheng WQ, Du X. CD133: a cancer stem cells marker, is used in colorectal cancers. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:2603–2611. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i17.2603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li Z. CD133: a stem cell biomarker and beyond. Exp Hematol Oncol. 2013;2:17. doi: 10.1186/2162-3619-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tabu K, Sasai K, Kimura T, Wang L, Aoyanagi E, Kohsaka S, Tanino M, Nishihara H, Tanaka S. Promoter hypomethylation regulates CD133 expression in human gliomas. Cell Res. 2008;18:1037–1046. doi: 10.1038/cr.2008.270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fargeas CA, Huttner WB, Corbeil D. Nomenclature of prominin-1 (CD133) splice variants - an update. Tissue Antigens. 2007;69:602–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.2007.00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu Y, Flint A, Dvorin EL, Bischoff J. AC133-2, a novel isoform of human AC133 stem cell antigen. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:20711–20716. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202349200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Irollo E, Pirozzi G. CD133: to be or not to be, is this the real question? Am J Transl Res. 2013;5:563–581. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Friel AM, Zhang L, Curley MD, Therrien VA, Sergent PA, Belden SE, Borger DR, Mohapatra G, Zukerberg LR, Foster R, Rueda BR. Epigenetic regulation of CD133 and tumorigenicity of CD133 positive and negative endometrial cancer cells. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2010;8:147. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-8-147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yan Y, Zuo X, Wei D. Concise Review: Emerging Role of CD44 in Cancer Stem Cells: A Promising Biomarker and Therapeutic Target. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2015;4:1033–1043. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen C, Zhao S, Karnad A, Freeman JW. The biology and role of CD44 in cancer progression: therapeutic implications. J Hematol Oncol. 2018;11:64. doi: 10.1186/s13045-018-0605-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia P, Xu XY. Prognostic significance of CD44 in human colon cancer and gastric cancer: Evidence from bioinformatic analyses. Oncotarget. 2016;7:45538–45546. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Todaro M, Gaggianesi M, Catalano V, Benfante A, Iovino F, Biffoni M, Apuzzo T, Sperduti I, Volpe S, Cocorullo G, Gulotta G, Dieli F, De Maria R, Stassi G. CD44v6 is a marker of constitutive and reprogrammed cancer stem cells driving colon cancer metastasis. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:342–356. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eom DW, Hong SM, Kim G, Bae YK, Jang KT, Yu E. Prognostic Significance of CD44v6, CD133, CD166, and ALDH1 Expression in Small Intestinal Adenocarcinoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2015;23:682–688. doi: 10.1097/PAI.0000000000000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zeilstra J, Joosten SP, van Andel H, Tolg C, Berns A, Snoek M, van de Wetering M, Spaargaren M, Clevers H, Pals ST. Stem cell CD44v isoforms promote intestinal cancer formation in Apc(min) mice downstream of Wnt signaling. Oncogene. 2014;33:665–670. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Müller I, Wischnewski F, Pantel K, Schwarzenbach H. Promoter- and cell-specific epigenetic regulation of CD44, Cyclin D2, GLIPR1 and PTEN by methyl-CpG binding proteins and histone modifications. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:297. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Saint-André V, Batsché E, Rachez C, Muchardt C. Histone H3 lysine 9 trimethylation and HP1γ favor inclusion of alternative exons. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:337–344. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weidle UH, Eggle D, Klostermann S, Swart GW. ALCAM/CD166: cancer-related issues. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2010;7:231–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Park IK, Liu R, Wang X, Cho RW, Hoey T, Gurney A, Huang EH, Simeone DM, Shelton AA, Parmiani G, Castelli C, Clarke MF. Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10158–10163. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703478104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kemper K, Grandela C, Medema JP. Molecular identification and targeting of colorectal cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 2010;1:387–395. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ikeda K, Quertermous T. Molecular isolation and characterization of a soluble isoform of activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule that modulates endothelial cell function. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:55315–55323. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407776200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.King JA, Tan F, Mbeunkui F, Chambers Z, Cantrell S, Chen H, Alvarez D, Shevde LA, Ofori-Acquah SF. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation and prognostic significance of activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule in cancer. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:266. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wei SH, Brown R, Huang TH. Aberrant DNA methylation in ovarian cancer: is there an epigenetic predisposition to drug response? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;983:243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb05979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baretti M, Azad NS. The role of epigenetic therapies in colorectal cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2018;42:530–547. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Azad N, Zahnow CA, Rudin CM, Baylin SB. The future of epigenetic therapy in solid tumours--lessons from the past. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2013;10:256–266. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2013.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McGranahan N, Swanton C. Biological and therapeutic impact of intratumor heterogeneity in cancer evolution. Cancer Cell. 2015;27:15–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.S Franco S, Szczesna K, Iliou MS, Al-Qahtani M, Mobasheri A, Kobolák J, Dinnyés A. In vitro models of cancer stem cells and clinical applications. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:738. doi: 10.1186/s12885-016-2774-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ahuja N, Easwaran H, Baylin SB. Harnessing the potential of epigenetic therapy to target solid tumors. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:56–63. doi: 10.1172/JCI69736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brown R, Curry E, Magnani L, Wilhelm-Benartzi CS, Borley J. Poised epigenetic states and acquired drug resistance in cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14:747–753. doi: 10.1038/nrc3819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sharma A, Vatapalli R, Abdelfatah E, Wyatt McMahon K, Kerner Z, A Guzzetta A, Singh J, Zahnow C, B Baylin S, Yerram S, Hu Y, Azad N, Ahuja N. Hypomethylating agents synergize with irinotecan to improve response to chemotherapy in colorectal cancer cells. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0176139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mao M, Tian F, Mariadason JM, Tsao CC, Lemos R, Jr, Dayyani F, Gopal YN, Jiang ZQ, Wistuba II, Tang XM, Bornman WG, Bollag G, Mills GB, Powis G, Desai J, Gallick GE, Davies MA, Kopetz S. Resistance to BRAF inhibition in BRAF-mutant colon cancer can be overcome with PI3K inhibition or demethylating agents. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:657–667. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Huang TH, Wu SY, Huang YJ, Wei PL, Wu AT, Chao TY. The identification and validation of Trichosstatin A as a potential inhibitor of colon tumorigenesis and colon cancer stem-like cells. Am J Cancer Res. 2017;7:1227–1237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pelosof L, Yerram S, Armstrong T, Chu N, Danilova L, Yanagisawa B, Hidalgo M, Azad N, Herman JG. GPX3 promoter methylation predicts platinum sensitivity in colorectal cancer. Epigenetics. 2017;12:540–550. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1265711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vasaikar SV, Straub P, Wang J, Zhang B. LinkedOmics: analyzing multi-omics data within and across 32 cancer types. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:D956–D963. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pérez-Salvia M, Esteller M. Bromodomain inhibitors and cancer therapy: From structures to applications. Epigenetics. 2017;12:323–339. doi: 10.1080/15592294.2016.1265710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aguirre-Gamboa R, Gomez-Rueda H, Martínez-Ledesma E, Martínez-Torteya A, Chacolla-Huaringa R, Rodriguez-Barrientos A, Tamez-Peña JG, Treviño V. SurvExpress: an online biomarker validation tool and database for cancer gene expression data using survival analysis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74250. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Azad NS, El-Khoueiry A, Yin J, Oberg AL, Flynn P, Adkins D, Sharma A, Weisenberger DJ, Brown T, Medvari P, Jones PA, Easwaran H, Kamel I, Bahary N, Kim G, Picus J, Pitot HC, Erlichman C, Donehower R, Shen H, Laird PW, Piekarz R, Baylin S, Ahuja N. Combination epigenetic therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) with subcutaneous 5-azacitidine and entinostat: a phase 2 consortium/stand up 2 cancer study. Oncotarget. 2017;8:35326–35338. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.15108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bauman J, Verschraegen C, Belinsky S, Muller C, Rutledge T, Fekrazad M, Ravindranathan M, Lee SJ, Jones D. A phase I study of 5-azacytidine and erlotinib in advanced solid tumor malignancies. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:547–554. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1729-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Overman MJ, Morris V, Moinova H, Manyam G, Ensor J, Lee MS, Eng C, Kee B, Fogelman D, Shroff RT, LaFramboise T, Mazard T, Feng T, Hamilton S, Broom B, Lutterbaugh J, Issa JP, Markowitz SD, Kopetz S. Phase I/II study of azacitidine and capecitabine/oxaliplatin (CAPOX) in refractory CIMP-high metastatic colorectal cancer: evaluation of circulating methylated vimentin. Oncotarget. 2016;7:67495–67506. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.11317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schwartsmann G, Schunemann H, Gorini CN, Filho AF, Garbino C, Sabini G, Muse I, DiLeone L, Mans DR. A phase I trial of cisplatin plus decitabine, a new DNA-hypomethylating agent, in patients with advanced solid tumors and a follow-up early phase II evaluation in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2000;18:83–91. doi: 10.1023/a:1006388031954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Appleton K, Mackay HJ, Judson I, Plumb JA, McCormick C, Strathdee G, Lee C, Barrett S, Reade S, Jadayel D, Tang A, Bellenger K, Mackay L, Setanoians A, Schätzlein A, Twelves C, Kaye SB, Brown R. Phase I and pharmacodynamic trial of the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor decitabine and carboplatin in solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4603–4609. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.8688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garrido-Laguna I, McGregor KA, Wade M, Weis J, Gilcrease W, Burr L, Soldi R, Jakubowski L, Davidson C, Morrell G, Olpin JD, Boucher K, Jones D, Sharma S. A phase I/II study of decitabine in combination with panitumumab in patients with wild-type (wt) KRAS metastatic colorectal cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2013;31:1257–1264. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-9947-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Toden S, Tran HM, Tovar-Camargo OA, Okugawa Y, Goel A. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate targets cancer stem-like cells and enhances 5-fluorouracil chemosensitivity in colorectal cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:16158–16171. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.7567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang PM, Lin YT, Shun CT, Lin SH, Wei TT, Chuang SH, Wu MS, Chen CC. Zebularine inhibits tumorigenesis and stemness of colorectal cancer via p53-dependent endoplasmic reticulum stress. Sci Rep. 2013;3:3219. doi: 10.1038/srep03219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Feldman M, Levy D. Peptide inhibition of the SETD6 methyltransferase catalytic activity. Oncotarget. 2017;9:4875–4885. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.23591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kaniskan HÜ, Eram MS, Zhao K, Szewczyk MM, Yang X, Schmidt K, Luo X, Xiao S, Dai M, He F, Zang I, Lin Y, Li F, Dobrovetsky E, Smil D, Min SJ, Lin-Jones J, Schapira M, Atadja P, Li E, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Arrowsmith CH, Brown PJ, Liu F, Yu Z, Vedadi M, Jin J. Discovery of Potent and Selective Allosteric Inhibitors of Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 3 (PRMT3) J Med Chem. 2018;61:1204–1217. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b01674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wu H, Zheng W, Eram MS, Vhuiyan M, Dong A, Zeng H, He H, Brown P, Frankel A, Vedadi M, Luo M, Min J. Structural basis of arginine asymmetrical dimethylation by PRMT6. Biochem J. 2016;473:3049–3063. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20160537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chimenti F, Bizzarri B, Maccioni E, Secci D, Bolasco A, Chimenti P, Fioravanti R, Granese A, Carradori S, Tosi F, Ballario P, Vernarecci S, Filetici P. A novel histone acetyltransferase inhibitor modulating Gcn5 network: cyclopentylidene-[4-(4'-chlorophenyl)thiazol-2-yl)hydrazone. J Med Chem. 2009;52:530–536. doi: 10.1021/jm800885d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Aquea F, Timmermann T, Herrera-Vásquez A. Chemical inhibition of the histone acetyltransferase activity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;483:664–668. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.12.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wheler JJ, Janku F, Falchook GS, Jackson TL, Fu S, Naing A, Tsimberidou AM, Moulder SL, Hong DS, Yang H, Piha-Paul SA, Atkins JT, Garcia-Manero G, Kurzrock R. Phase I study of anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody bevacizumab and histone deacetylase inhibitor valproic acid in patients with advanced cancers. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2014;73:495–501. doi: 10.1007/s00280-014-2384-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Münster P, Marchion D, Bicaku E, Schmitt M, Lee JH, DeConti R, Simon G, Fishman M, Minton S, Garrett C, Chiappori A, Lush R, Sullivan D, Daud A. Phase I trial of histone deacetylase inhibition by valproic acid followed by the topoisomerase II inhibitor epirubicin in advanced solid tumors: a clinical and translational study. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1979–1985. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pili R, Salumbides B, Zhao M, Altiok S, Qian D, Zwiebel J, Carducci MA, Rudek MA. Phase I study of the histone deacetylase inhibitor entinostat in combination with 13-cis retinoic acid in patients with solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:77–84. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ngamphaiboon N, Dy GK, Ma WW, Zhao Y, Reungwetwattana T, DePaolo D, Ding Y, Brady W, Fetterly G, Adjei AA. A phase I study of the histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor entinostat, in combination with sorafenib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 2015;33:225–232. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0174-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Strickler JH, Starodub AN, Jia J, Meadows KL, Nixon AB, Dellinger A, Morse MA, Uronis HE, Marcom PK, Zafar SY, Haley ST, Hurwitz HI. Phase I study of bevacizumab, everolimus, and panobinostat (LBH-589) in advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;70:251–258. doi: 10.1007/s00280-012-1911-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ree AH, Dueland S, Folkvord S, Hole KH, Seierstad T, Johansen M, Abrahamsen TW, Flatmark K. Vorinostat, a histone deacetylase inhibitor, combined with pelvic palliative radiotherapy for gastrointestinal carcinoma: the Pelvic Radiation and Vorinostat (PRAVO) phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:459–464. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wilson PM, El-Khoueiry A, Iqbal S, Fazzone W, LaBonte MJ, Groshen S, Yang D, Danenberg KD, Cole S, Kornacki M, Ladner RD, Lenz HJ. A phase I/II trial of vorinostat in combination with 5-fluorouracil in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer who previously failed 5-FU-based chemotherapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;65:979–988. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1236-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Fakih MG, Groman A, McMahon J, Wilding G, Muindi JR. A randomized phase II study of two doses of vorinostat in combination with 5-FU/LV in patients with refractory colorectal cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:743–751. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1762-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Munster PN, Marchion D, Thomas S, Egorin M, Minton S, Springett G, Lee JH, Simon G, Chiappori A, Sullivan D, Daud A. Phase I trial of vorinostat and doxorubicin in solid tumours: histone deacetylase 2 expression as a predictive marker. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:1044–1050. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Deming DA, Ninan J, Bailey HH, Kolesar JM, Eickhoff J, Reid JM, Ames MM, McGovern RM, Alberti D, Marnocha R, Espinoza-Delgado I, Wright J, Wilding G, Schelman WR. A Phase I study of intermittently dosed vorinostat in combination with bortezomib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest New Drugs. 2014;32:323–329. doi: 10.1007/s10637-013-0035-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Whitehead RP, Rankin C, Hoff PM, Gold PJ, Billingsley KG, Chapman RA, Wong L, Ward JH, Abbruzzese JL, Blanke CD. Phase II trial of romidepsin (NSC-630176) in previously treated colorectal cancer patients with advanced disease: a Southwest Oncology Group study (S0336) Invest New Drugs. 2009;27:469–475. doi: 10.1007/s10637-008-9190-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pauer LR, Olivares J, Cunningham C, Williams A, Grove W, Kraker A, Olson S, Nemunaitis J. Phase I study of oral CI-994 in combination with carboplatin and paclitaxel in the treatment of patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Invest. 2004;22:886–896. doi: 10.1081/cnv-200039852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Patel KR, Scott E, Brown VA, Gescher AJ, Steward WP, Brown K. Clinical trials of resveratrol. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1215:161–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rotili D, Tarantino D, Nebbioso A, Paolini C, Huidobro C, Lara E, Mellini P, Lenoci A, Pezzi R, Botta G, Lahtela-Kakkonen M, Poso A, Steinkühler C, Gallinari P, De Maria R, Fraga M, Esteller M, Altucci L, Mai A. Discovery of salermide-related sirtuin inhibitors: binding mode studies and antiproliferative effects in cancer cells including cancer stem cells. J Med Chem. 2012;55:10937–10947. doi: 10.1021/jm3011614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lin H, Li Q, Li Q, Zhu J, Gu K, Jiang X, Hu Q, Feng F, Qu W, Chen Y, Sun H. Small molecule KDM4s inhibitors as anti-cancer agents. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2018;33:777–793. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1455676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Bar-Sela G, Epelbaum R, Schaffer M. Curcumin as an anti-cancer agent: review of the gap between basic and clinical applications. Curr Med Chem. 2010;17:190–197. doi: 10.2174/092986710790149738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wang J, Chen C, Wang S, Zhang Y, Yin P, Gao Z, Xu J, Feng D, Zuo Q, Zhao R, Chen T. Bufalin Inhibits HCT116 Colon Cancer Cells and Its Orthotopic Xenograft Tumor in Mice Model through Genes Related to Apoptotic and PTEN/AKT Pathways. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:457193. doi: 10.1155/2015/457193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wapenaar H, Dekker FJ. Histone acetyltransferases: challenges in targeting bi-substrate enzymes. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:59. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0225-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fogelman D, Cubillo A, García-Alfonso P, Mirón MLL, Nemunaitis J, Flora D, Borg C, Mineur L, Vieitez JM, Cohn A, Saylors G, Assad A, Switzky J, Zhou L, Bendell J. Randomized, double-blind, phase two study of ruxolitinib plus regorafenib in patients with relapsed/refractory metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2018;7:5382–5393. doi: 10.1002/cam4.1703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Chu-Farseeva YY, Mustafa N, Poulsen A, Tan EC, Yen JJY, Chng WJ, Dymock BW. Design and synthesis of potent dual inhibitors of JAK2 and HDAC based on fusing the pharmacophores of XL019 and vorinostat. Eur J Med Chem. 2018;158:593–619. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Kobza KA, Chaiseeda K, Sarath G, Takacs JM, Zempleni J. Biotinyl-methyl 4-(amidomethyl)benzoate is a competitive inhibitor of human biotinidase. J Nutr Biochem. 2008;19:826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moustakim M, Clark PG, Trulli L, Fuentes de Arriba AL, Ehebauer MT, Chaikuad A, Murphy EJ, Mendez-Johnson J, Daniels D, Hou CD, Lin YH, Walker JR, Hui R, Yang H, Dorrell L, Rogers CM, Monteiro OP, Fedorov O, Huber KV, Knapp S, Heer J, Dixon DJ, Brennan PE. Discovery of a PCAF Bromodomain Chemical Probe. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2017;56:827–831. doi: 10.1002/anie.201610816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.He Y, Selvaraju S, Curtin ML, Jakob CG, Zhu H, Comess KM, Shaw B, The J, Lima-Fernandes E, Szewczyk MM, Cheng D, Klinge KL, Li HQ, Pliushchev M, Algire MA, Maag D, Guo J, Dietrich J, Panchal SC, Petros AM, Sweis RF, Torrent M, Bigelow LJ, Senisterra G, Li F, Kennedy S, Wu Q, Osterling DJ, Lindley DJ, Gao W, Galasinski S, Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Vedadi M, Buchanan FG, Arrowsmith CH, Chiang GG, Sun C, Pappano WN. The EED protein-protein interaction inhibitor A-395 inactivates the PRC2 complex. Nat Chem Biol. 2017;13:389–395. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]