Abstract

Individuals who have ocular features of albinism and skin pigmentation in keeping with their familial background present a considerable diagnostic challenge. Timely diagnosis through genomic testing can help avert diagnostic odysseys and facilitates accurate genetic counselling and tailored specialist management. Here, we report the clinical and gene panel testing findings in 12 children with presumed ocular albinism. A definitive molecular diagnosis was made in 8/12 probands (67%) and a possible molecular diagnosis was identified in a further 3/12 probands (25%). TYR was the most commonly mutated gene in this cohort (75% of patients, 9/12). A disease-causing TYR haplotype comprised of two common, functional polymorphisms, TYR c.[575 C > A;1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)], was found to be particularly prevalent. One participant had GPR143-associated X-linked ocular albinism and another proband had biallelic variants in SLC38A8, a glutamine transporter gene associated with foveal hypoplasia and optic nerve misrouting without pigmentation defects. Intriguingly, 2/12 individuals had a single, rare, likely pathogenic variant in each of TYR and OCA2 – a significant enrichment compared to a control cohort of 4046 individuals from the 100,000 genomes project pilot dataset. Overall, our findings highlight that panel-based genetic testing is a clinically useful test with a high diagnostic yield in children with partial/ocular albinism.

Subject terms: Paediatric research, Genetics research, Molecular medicine, Disease genetics, Eye manifestations

Introduction

Albinism is a group of hereditary conditions characterised by decreased or absent ocular pigmentation and variable skin/hair pigmentation. It can be broadly subdivided into oculocutaneous albinism (OCA) and ocular albinism (OA) [MIM: 300500]. Syndromic forms of albinism have also been described (including Hermansky-Pudlak [MIM: 203300] and Chediak-Higashi syndromes [MIM: 214500]); in these rare disorders, pigmentation abnormalities co-exist with other pathological alterations1. Ocular features are present in all albinism patients and are characteristic of the condition; these may include nystagmus, foveal hypoplasia, fundal hypopigmentation, iris transillumination and optic nerve misrouting. In contrast, cutaneous features may or may not be present2.

Albinism, and OCA in particular, exhibits significant clinical and genetic heterogeneity3,4. Notably, skin pigmentation abnormalities can often be difficult to evaluate, especially in people with light-skinned familial backgrounds. In such cases, there is significant phenotypic overlap with a range of other ophthalmic conditions including X-linked idiopathic congenital nystagmus [MIM: 310700]5, SLC38A8-associated foveal hypoplasia (also known as FHONDA [MIM: 609218], a condition including optic nerve decussation defects and, in some cases, anterior segment dysgenesis)6, and dominant PAX6-related oculopathy [MIM: 136520]7. Obtaining a precise diagnosis and distinguishing between these different entities is particularly important as it enables accurate genetic counselling and personally tailored surveillance and management decisions (e.g. dermatological input). However, the current diagnostic pathway for these individuals is often prolonged, cumbersome and frequently unsuccessful. Investigations such as slit lamp examination, macular optical coherence tomography and visual electrophysiology can be helpful and are typically used to formally diagnose iris transillumination, foveal hypoplasia and optic nerve misrouting respectively. However, performing such tests in infants and young children can be challenging as co-operation for several minutes at a time is required. Furthermore, the ocular signs of partial albinism can be subtle and certain features may be absent in mild cases8. As a result, multiple clinic visits over years and several investigations may be needed to reach a formal diagnosis.

The use of genetic testing early in the care pathway offers significant potential for accelerating diagnosis in individuals suspected to have partial OCA. Over the past decade, advances in DNA sequencing technologies including gene panel testing and genome sequencing have revolutionised diagnostics across many heterogeneous inherited disorders9. A recent report on the use of a panel-based sequencing approach in a large cohort of patients with albinism found that a definitive molecular diagnosis could be obtained in 72% of cases10. A notable finding of this study was the confirmation of a TYR allele containing two relatively common variants in cis TYR c.[575 C > A;1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] as a prevalent cause of mild albinism when in trans with a TYR pathogenic variant3,10,11. Despite this recent progress in dissecting the molecular pathology of albinism, our understanding of the genetic basis of partial OCA remains incomplete.

Here, we studied 12 individuals who presented diagnostic challenges as they had some ocular features of albinism but their skin was not hypopigmented in the context of their family. Phenotypic and gene panel testing results are discussed. The clinical utility of early genomic testing in this group of patients is highlighted.

Results

Clinical findings

We identified 12 children (under 16 years of age at time of testing) with nystagmus, at least one other ocular feature of albinism, and no apparent skin hypopigmentation in the context of their family. Their clinical features are summarised in Table 1. Nystagmus was the presenting symptom in all patients and the median age at referral for genetic testing was 5.5 years. Foveal hypoplasia was suspected in 11/12 and iris transillumination was detected in 7/12. Possible electrophysiological evidence of optic nerve misrouting was identified at some point in the life of 9/10 patients tested; 3 of these 9 children were tested more than once and there was variability in the visual evoked potential (VEP) findings between visits (Table 1). For example, proband 2 had electrodiagnostic studies at age 9 months which showed minimal crossed asymmetry. When the test was repeated at age 2 years, there was no evidence of crossed asymmetry but a further assessment at age 14 years showed marked crossed asymmetry. This is perhaps not surprising as the visual system undergoes dramatic maturationial change in the first few years of life which is manifested in flash and pattern VEPs12,13, leading to the recommendation to wait until 4 years of age before repeating ambiguous VEPs.

Table 1.

Clinical findings in 12 children with ocular features of albinism and no obvious skin pigmentation abnormalities.

| proband ID | age at genetic testing (years) | sex | iris transillumination | foveal hypoplasia | fundal hypopigmentation | age at VEP testing (years) | VEP crossed asymmetry (pattern & flash VEP score) | relevant family history |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <1 | M | no | yes | yes | <1 | possible (P-1, F1) | none reported |

| 2 | 14 | F | no | yes | yes | <1; 2; 14 | probable (P-1, F2); no (P-1, F0); yes (P3, F3) | none reported |

| 3 | 1 | M | yes | yes | yes | not tested | not tested | none reported |

| 4 | 3 | M | yes | yes | yes | <1 | yes (P3, F3) | mother with iris transillumination & foveal hypoplasia |

| 5 | 6 | M | yes | yes | yes | 5 | yes (P3, F3) | identical twin affected |

| 6 | 1 | M | yes | yes | yes | <1 | yes (P3, F3) | none reported |

| 7 | 8 | M | yes | yes | yes | <1 | probable (P2, F1) | none reported |

| 8 | 11 | F | yes | yes | yes | not tested | not tested | brother affected |

| 9 | 1 | F | yes | yes | yes | 1 | no (P0, F0) | none reported |

| 10 | 7 | F | no | yes | yes | 3; 6 | probable (P2, F0); probable (P0, F2) | none reported |

| 11 | 7 | M | no | yes | no | 1; 4 | possible (P1, F0); no (P0, F0) | half-brother of paternal grandmother with nystagmus |

| 12 | 5 | M | no | no | no | 2 | yes (P1, F3) | parental consanguinity |

VEP, visual evoked potential; M, male; F, female. All study participants had skin pigmentation in keeping with their familial background. Other clinical features included prominent posterior embryotoxa in proband 2, easy bruising in proband 9 and mild developmental delay in proband 12.

Pattern (P) and flash (F) VEP scores are shown. A score of [−1] corresponds to inadequate signal, either due to poor cooperation or simply because spatial vision was too poor. A score of [0] suggests no crossed asymmetry (i.e. the right-left difference plots for right and left eyes were indistinguishable). A score of [1] denotes possible crossed asymmetry (i.e. whilst most components are not asymmetrical, one or two are). A score of [2] suggests probable crossed asymmetry (i.e. crossed asymmetry is partial or the polarity of the components is reversed but the phase is shifted). A score of [3] denotes definite crossed asymmetry (i.e. while right-left interhemispheric difference plots may be of differing amplitude, their waveforms are more or less mirror images of each other.

Genetic findings and diagnostic pick-up rate

A probable molecular diagnosis was identified in 8/12 patients (67%); a possible molecular diagnosis was identified in a further 3/12 patients (25%). Overall, 10/12 children were found to have pathogenic variants in OCA or OA-associated genes. The most frequently implicated gene was TYR: sequence alterations in this gene were identified in 75% of patients (9/12). One child was found to have a hemizygous pathogenic variant in GPR143 [MIM: 300808], the gene associated with X-linked OA, and another child was found to have a compound heterozygous changes in SLC38A8, a gene associated with foveal hypoplasia and optic nerve misrouting without pigmentation abnormalities. We identified four previously unreported disease-causing changes: two in SLC38A8, one in TYR and one in OCA2. The genetic findings in all study participants can be found in Table 2 and further details on the individual variants are in Table 3. Familial segregation is discussed below and family trees are provided in the Supplementary File.

Table 2.

Genetic findings in 12 children with ocular features of albinism and no obvious skin pigmentation abnormalities.

| proband ID | gene panel used for testing (number of genes evaluated) | variant 1 | variant 2 | variant 3 | samples available for segregation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ocular/oculocutanous albinism (18) | GPR143 c.659-1 G > A | — | — | mother |

| 2 | nystagmus & foveal hypoplasia (26) | SLC38A8 c.534 C > G p.(Ile178Met) | SLC38A8 exon 2 to 5 deletion | — | none |

| 3 | ocular/oculocutanous albinism (18) | TYR c.1217 C > T p.(Pro406Leu) | TYR c.575 C > A p.(Ser192Tyr) | TYR 1205 G > A p.(Arg402Gln) | none |

| 4 | optic nerve disorders (40) | TYR c.1118 C > A p.(Thr373Lys) | TYR c.575 C > A p.(Ser192Tyr) | TYR 1205 G > A p.(Arg402Gln) | mother & father |

| 5 | ocular/oculocutanous albinism (18) | TYR c.823 G > T p.(Val275Phe) | TYR c.[575 C > A; 1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] | OCA2 c.1327 G > A p.(Val443Ile) | mother & father |

| 6 | nystagmus & foveal hypoplasia (26) | TYR c.1118 C > A p.(Thr373Lys) | TYR c.[575 C > A; 1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] | — | mother & father |

| 7 | nystagmus & foveal hypoplasia (26) | TYR c.[575 C > A; 1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] | TYR c.[575 C > A; 1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] | — | no |

| 8 | ocular/oculocutanous albinism (18) | TYR c.[575 C > A; 1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] | TYR c.[575 C > A; 1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] | TYRP1 c.208 G > A p.(Ala70Thr) | mother, father & affected brother |

| 9 | clinical exome | OCA2 c.1327 G > A p.(Val443Ile) | TYR c.575 C > A p.(Ser192Tyr) | TYR 1205 G > A p.(Arg402Gln) | no |

| 10 | nystagmus & foveal hypoplasia (26) | OCA2 c.2346deIG p.(Thr783Hisfs*2) | TYR c.1392dupT p.(Lys465*) | — | mother |

| 11 | nystagmus & foveal hypoplasia (26) | OCA2 c.1441 G > A, (p.Ala481Thr) | TYR c.1217 C > T, p.(Pro406Leu) | — | mother |

| 12 | ocular/oculocutanous albinism (18) | no pathogenic variant identified | — | — | no |

The genes and transcripts included in each gene panel can be found in Supplementary Table 1. The results of segregation are discussed in the text and family trees are provided in the Supplementary File.

Table 3.

Analysis of disease-associated variants identified in children with ocular features of albinism.

| gene | genotype | protein | probands affected | report describing the variant in association with albinism | gnomAD total frequency % (allele count) | polyphen-2 HumVar score | CADD score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GPR143 | c.659-1 G > A | not applicable | 1 | Han et al.15 | not detected (0/183,366) | not applicable | 26.5 |

| TYR | c.1217 C > T | p.(Pro406Leu) | 3,11 | Giebel et al.18 | 0.3918% (1,104/281,766) | 0.997 | 27.2 |

| TYR | c.[575 C > A; 1205 G > A] | p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] | 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 | Norman et al.3 | 25.02% (70,744/282,804) & 17.65% (49,703/281,606) | 0.974 & 0.994 | 24.2 & 29.4 |

| TYR | c.1118 C > A | p.(Thr373Lys) | 4, 6 | King et al.19 | 0.0354% (100/282,382) | 0.004 | 23.5 |

| TYR | c.823 G > T | p.(Val275Phe) | 5 | Giebel et al.18 | 0.0099% (28/282,378) | 0.42 | 11.17 |

| TYR | c.1392dupT | p.(Lys465*) | 10 | novel | not detected (0/251,158) | not applicable | not applicable |

| SLC38A8 | c.534 C > G | p.(Ile178Met) | 2 | novel | 0.0016% (4/250,998) | 0.701 | 22.1 |

| SLC38A8 | exon 2 to exon 5 deletion | exon 2 to exon 5 deletion | 2 | novel | not applicable | not applicable | not applicable |

| OCA2 | c.1327 G > A | p.(Val443Ile) | 5, 9 | Lee et al.20 | 0.3055% (860/281,442) | 0.998 | 27.0 |

| OCA2 | c.2346deIG | p.(Thr783Hisfs*2) | 10 | novel | not detected (0/251,472) | not applicable | not applicable |

| OCA2 | c.1441 G > A, | p.(Ala481Thr) | 11 | Yuasa et al.22 | 0.8427% (2,384/282,886) | 0.466 | 24.7 |

| TYRP1 | c.208 G > A | p.(Ala70Thr) | 8 | Marti et al.21 | 0.0242% (68/281,344) | 0.606 | 23.0 |

Polyphen-222 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/) predicts the impact of an amino acid substitution on a human protein using physical and comparative considerations. The output is a 0 to 1 score; the higher the score the more likely it is that the variant is pathogenic. Combined Annotation-Dependent Depletion23 (CADD; https://cadd.gs.washington.edu/) combines information from many different in silico tools and uses a support vector machine classifier. The CADD score ranges from 1 to 99; a higher score indicates greater pathogenicity. Values ≥10 are predicted to be the 10% most deleterious substitutions and ≥ 20 in the 1% most deleterious. The overall gnomAD26 (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) minor allele frequency is presented. Polyphen-2, CADD and gnoMAD were all accessed on 23/01/2019.

Proband 1

Proband 1, a 1-year-old white British male, was found to have the GPR143 c.659-1 G > A change in hemizygous state. This variant was not detected in a maternal sample and is not present in gnomAD14. It has, however, previously been reported in a Chinese male patient with OA15.

Proband 2

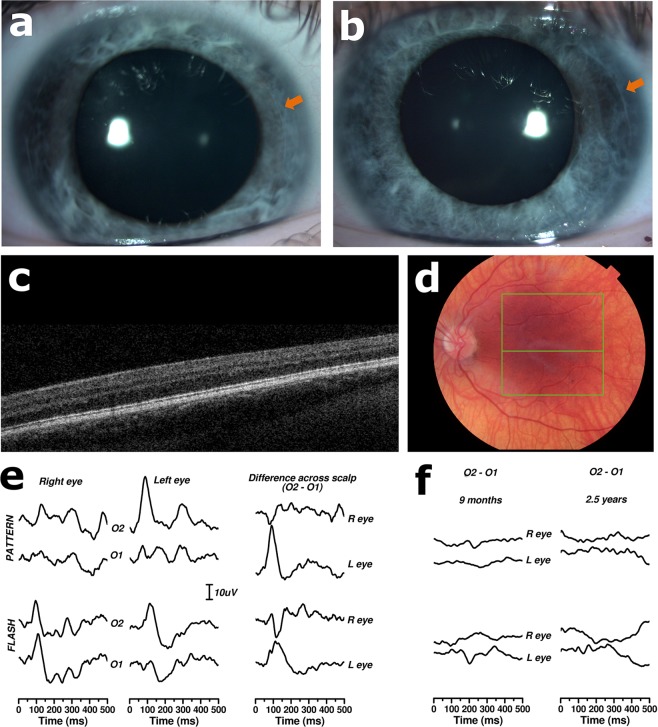

Proband 2, a 14-year-old white British female, was found to have compound heterozygous changes in the SLC38A8 gene; these included a heterozygous missense change c.534 C > G p.(Ile178Met) and a heterozygous large inframe deletion removing exons 2 to 5. The missense mutation has not been previously reported as disease causing. It is found at very low frequency in population databases and it is reported as possibly damaging by in silico tools (Table 3). The large deletion removes 167 amino acids (the total length of the protein is 435 amino acids) affecting 5 of the 11 transmembrane domains of this glutamine transporter. Notably, the patient has prominent posterior embryotoxa (Fig. 1). Such abnormalities have been described in 3 of the 9 families with SLC38A8-associated disease reported to date6,16,17.

Figure 1.

Ocular and electrodiagnostic findings in a patient with SLC38A8-associated disease (proband 2). (a,b) Anterior segment photographs of right (a) and left (b) eyes obtained at age 14 years. The arrows mark the location of the embryotoxa. (c,d) Linear optical coherence tomography (OCT) scan through the centre of the macula of the left eye demonstrating absence of the foveal depression in keeping with foveal hypoplasia. (c) The associated left colour fundus photograph highlighting the location of the scan (line in the middle of the green box) is also shown. This image (d) reveals that, although the central macula appears to be adequately pigmented, there is a degree of fundal hypopigmentation mid-peripherally. It is noteworthy that the proband is of white British background and her skin was not hypopigmented in the context of her family. These images were obtained when the patient was 12 years of age. (e) Monocular pattern and flash visual evoked potentials (VEPs) recorded from electrodes mounted 3 cm to right (O2) and left (O1) of midline. The patient was 14 years old at the time of testing. The difference plots are subtractions of left from right scalp recordings to show how scalp asymmetry is reversed in the two eyes (crossed asymmetry) when virtually all optic nerve fibres cross at the chiasm. (f) Difference plots recorded at age 9 months and 2.5 years, showing minimal or no crossed asymmetry; this is in contrast to the assessment at age 14 years, shown in (e), which was in keeping with marked crossed asymmetry.

Probands 3, 4, 5 and 6

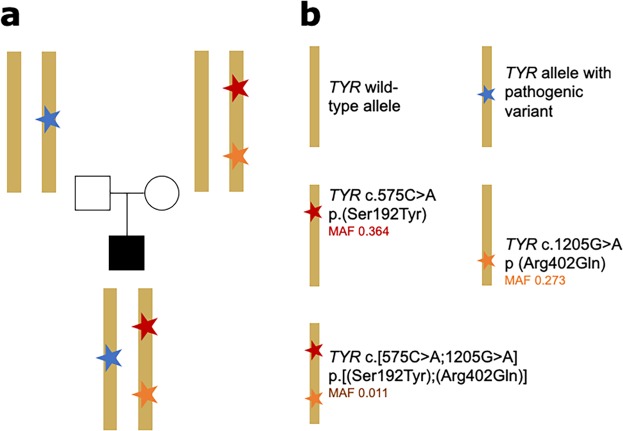

In four probands (3, 4, 5 and 6), we identified a known disease-associated TYR variant along with a genotype in keeping with the presence of the TYR complex haplotype p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] (Table 2; Fig. 2). It was possible to perform segregation analysis only in probands 4, 5 and 6 (please see Supplementary File for more details). For proband 4 it was not possible to verify cis/trans phase of the variants. In proband 5 and 6, the TYR variants p.(Arg402Gln) and p.(Ser192Tyr) were found to be in cis and the resultant haplotype – p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] – was verified as being in trans with known pathogenic TYR variants: TYR c.823 G > T p.(Val275Phe)18 in proband 5 and TYR c.1118 C > A p.Thr373Lys19 in proband 6 (Fig. 2). An established pathogenic variant in OCA2 – OCA2 c.1327 G > A p.(Val443Ile)20 – was also identified in proband 5.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the formation of the TYR c.[575 C > A;1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] complex allele. (a) Basic pedigree including parental haplotypes from an individual (proband 6) carrying the TYR complex allele (red & orange stars) in trans with a TYR pathogenic allele (blue star). (b) Figure key for (a) explaining the variants present in each allele. Notably, each of c.575 C > A p.(Ser192Tyr) and c.1205 G > A p (Arg402Gln) has been shown to predispose to decreased pigmentation40,41 and to result in reduced tyrosinase activity11. The minor allele frequencies (MAF) shown for these two variants are from the gnomAD variant database25 (accessed 23/01/2019, European non-Finnish population). The MAF shown for the c.[575 C > A;1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] complex allele is estimated using data from the “British in England & Scotland” subset of the 1000 genomes project3.

Probands 7 and 8

In probands 7 and 8, both the TYR p.(Arg402Gln) and p.(Ser192Tyr) variants were detected in a homozygous state. These two probands had all the cardinal ocular features of albinism but their skin pigmentation was in keeping with their wider family. Proband 8 was also found to have a rare TYRP1 variant: TYRP1 c.208 G > A p.(Ala70Thr). This variant is reported to be possibly damaging by in silico tools (Table 3) and a recent study identified the variant in a patient with albinism21. Proband 8 also has a 1-year-old brother with nystagmus who was also homozygous for TYR p.(Arg402Gln) and TYR p.(Ser192Tyr) but did not carry the TYRP1 p.(Ala70Thr) variant.

Probands 9, 10 and 11

Probands 9, 10 and 11 were found to have heterozygous disease-causing variants in each of the TYR and OCA2 genes. Proband 9 had a single, previously reported disease-associated variant in OCA2 – OCA2 p.(Val443Ile)20 – and is also heterozygous for the TYR c.575 C > A p.(Ser192Tyr) and TYR c.1205 G > A p.(Arg402Gln) variants; segregation analysis was not possible. Proband 10 had two previously unreported heterozygous truncating variants, one in TYR c.1392dupT p.(Lys465*) and one in OCA2 c.2346deIG p.(Thr783Hisfs*2). Her unaffected mother was found to only carry the TYR variant. Proband 11 harboured a previously reported disease-associated variant in TYR – TYR c.1217 C > T p.(Pro406Leu)18 – and a hypomorphic allele in OCA2 – OCA2 p.(Ala481Thr)22. This OCA2 change has previously been suspected to cause albinism in some patients but reports on ClinVar are conflicting23,24. A maternal sample was available for segregation revealing that the proband’s mother carried both the TYR and OCA2 alleles but in the absence of a clinical phenotype of partial OCA. This result raises questions over the penetrance/pathogenicity of the genotype in proband 11. However, according to the criteria outlined in the methods section, proband 11 meets the definition for having a possible molecular diagnosis.

Proband 12

In proband 12, no pathogenic variants were identified.

Prevalence of selected genotypes in an external cohort

To gain insights into the prevalence of certain combinations of variants in individuals without a clinical diagnosis of albinism, we interrogated the genomic data of 4046 individuals from the 100,000 genomes project pilot dataset25. First, we looked at how many individuals in this external dataset were homozygous for the TYR p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] haplotype (like probands 7 & 8); two of 4046 individuals were found to be homozygous for both TYR p.(Arg402Gln) and p.(Ser192Tyr). Then, we looked for individuals that have a genotype in keeping with the presence of the TYR p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] haplotype in combination with a rare (MAF < 0.047 in ExAC14) TYR variant (like probands 3–6). Six of the 4046 individuals in the external cohort met this criterion. In all these six cases data from other family members were available; we therefore assessed the phase of the variants in the complex TYR allele and found that in all these individuals p.(Arg402Gln) and p.(Ser192Tyr) were highly likely to occur in trans. Finally, we looked for individuals that had both a rare TYR variant and a rare OCA2 variant (like probands 10 & 11). One of the 4046 individuals in the external cohort met this criterion. Evaluation using the Fisher exact test revealed that each of these 3 variant combinations is significantly enriched in the patient cohort compared to the external, 100,000 genomes project pilot cohort (p-value of < 0.0001 for each of the 3 comparisons).

Discussion

Although the study of severe, complete albinism phenotypes is relatively straightforward, milder subtypes remain difficult to diagnose clinically. Recent studies have made considerable progress in appreciating the clinical heterogeneity and elucidating the genetic basis in this group of conditions3,8,10,26. Here, we identified a cohort of children who have ocular features of albinism and skin pigmentation that is in keeping with their familial background. Panel-based genetic testing was performed and the current utility of this investigation in clinical practice was evaluated

Detailed phenotyping of study participants highlighted the heterogeneity of partial albinism. There were varying combinations of ophthalmic symptoms and signs present in each child. This observation is in line with a recent study on the phenotypic spectrum of albinism that found no pathognomonic features for this condition8. This study by Kruijt and colleagues8 represents a significant milestone towards establishing clinical criteria for albinism. However, although the described classification system is precise and carefully designed, it is also dependent upon high-quality phenotypic information (such as OCT-based grading of foveal hypoplasia) that can be challenging to routinely and consistently obtain in infants and young children. Given this issue and the significant clinical variability, genetic testing represents an important method for obtaining a precise, timely diagnosis in children with partial albinism. We utilised a panel test for genes known to cause albinism or plausible differential diagnoses which in all cases contained 18 common genes linked to albinism (Supplementary Table 1). We established a high diagnostic rate with 92% (11/12) of study participants receiving a probable or possible molecular diagnosis. This finding is comparable to that of a recent report on albinism that identified biallelic or monoallelic variants in relevant genes in 85% (837/990) of patients with albinism10. We found that most individuals in the present partial albinism cohort (10/12) had mutations in OA/OCA-related genes. TYR was the most frequently mutated gene: 6/8 (75%) patients who received probable molecular diagnosis had TYR-associated disease. In contrast, Lasseaux and colleagues, in a larger and more heterogeneous albinism cohort (including individuals with both complete and incomplete forms), reported identifying TYR mutations in 300/717 (42%) of the solved cases s10.

Notably, one patient in in the present study had SLC38A8-associated disease, an important differential diagnosis of partial albinism. SLC38A8 encodes a glutamate transporter that, unlike OA/OCA-related genes, has not been linked with defects in melanin biosynthesis or melanocyte differentiation6. Individuals with this condition present with nystagmus, foveal hypoplasia and optic nerve misrouting without iris, fundal or skin pigmentation defects (Fig. 1)6,16,17. Prominent posterior embryotoxa are present in some cases (including proband 2) and the presence of this anterior segment sign in an individual with partial albinism should raise suspicion for SLC38A8-associated disease.

In this cohort, TYR c.[575 C > A;1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] was the most common pathogenic allele as it was suspected to be present in 7/12 patients. The two genotypes TYR c.575 C > A and TYR c.1205 G > A have arisen on different ancestral haplotypes27 and each is known to reduce pigmentation28,29. Individually both variants are common (gnomAD frequencies: 25.02% and 17.65% respectively) but their presence together on a recombinant haplotype TYR c.[575 C > A;1205 G > A] p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] is a relatively rare event, predicted to be found in British patients at a frequency of 1.1%3. This haplotype has been found to lead to an additive decrease in tyrosinase function compared to each of the two variants individually (Fig. 2)11. Recent genome sequencing in nine individuals with albinism carrying this haplotye and follow-up functional work did not support any other variants on the haplotype as having a role in reducing TYR function26. It appears likely that this haplotype is pathogenic because the combination of these two functional coding variants reduces TYR production to pathogenic levels. This recombination of common single polymorphisms that aberrantly affect protein function onto a single haplotype, with resulting significant decrease in protein function (in an additive or multiplicative fashion) to pathogenic levels is a rarely reported mechanism. Although initially described as a ‘tri-allelic genotype’ by Norman et al. (2017), we feel it would be better to classify this as a ‘complex’ or ‘pathogenic’ haplotype, like Grønskov et al.26, to reflect these mechanistic underpinnings. Such a ‘complex/pathogenic’ haplotype has also recently been noted in ABCA4-related eye disease30. The discovery of such alleles re-enforces the importance of considering cis-genomic context in mutational analysis31. Current genetic laboratory pipelines are often suboptimally set up to identify these complex disease-causing haplotypes as data are filtered based on the rarity of individual variants rather than haplotypes. However, complex/pathogenic alleles may underlie some of the current missing heritability in rare genetic disease. Detailed analysis of individuals with monoallelic pathogenic variants in genes associated with recessive disorders offers the best chance to identify such haplotypes, as has happened serendipitously in albinism.

We identified two individuals with partial albinism that were homozygous for the TYR p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] allele. Compared to a control cohort from the 100,000 genomes project pilot dataset, this genotype is significantly enriched among albinism patients. Grønskov et al.26 identified six further individuals with mild albinism that were homozygous for the haplotype in their cohort of 93 albinism patients; five of these individuals were clinically diagnosed with OA – supporting the mild cutaneous phenotype associated with this genotype. Grønskov et al.26 also noted that, given the high predicted carrier frequency of this haplotype in the general population, (i) it would be surprising if it were a fully penetrant disease-associated allele and (ii) mild cases of albinism may remain undiagnosed/asymptomatic especially in light-skinned population. Indeed, homozygosity for the complex haplotype may only cause ocular de-pigmentation that is significant enough to prompt tertiary referral for ophthalmological complications upon an already low pigmentation background.

We identified two individuals with partial albinism and monoallelic rare variants in both TYR and OCA2 – a significant enrichment compared to a control cohort from the 100,000 genomes project pilot dataset. We with “considered these individuals as having a possible molecular diagnosis given that they have a variant in a gene linked with recessive disease and a strong genotype-phenotype fit. Intriguingly, oligo/digenic inheritance mechanisms have been hypothesised previously in albinism32–34 and given that melanin biosynthesis is known to be an interactive pathway this remains an attractive hypothesis35,36. However, convincing evidence is yet to be reported in the scientific literature.

This study has a number of limitations. A notable one relates to the fact that the panel tests utilised here did not include three genes previously linked to rare forms of ‘syndromic albinism’, HSP137, AP3D138, MITF39, and one gene recently linked to ocular albinism, GNAI340. In addition to being unable to rule out defects in these four genes, we did not evaluate non-coding variation associated with known albinism-related genes. Further studies of probands and families with an eluding molecular diagnosis would be of interest to identify the sources of the remaining missing heritability in albinism.

In conclusion, we report that panel-based genetic testing has a high diagnostic rate in ocular/partial albinism suspects. It has the potential to allow timely diagnosis whilst avoiding multiple clinical assessments and diagnostic tests. Also, it impacts clinical management; for example, individuals with confirmed OCA will receive appropriate support and advice regarding skin care. Notably, variants in OCA-related genes account for most genetic diagnoses in this cohort of patients. Findings in a small but significant minority of individuals with partial albinism suggest that investigating the penetrance of TYR variants and exploring a digenic inheritance model involving TYR and OCA2 would be of interest. However, large, collaborative research cohorts with high quality phenotyping and familial segregation data would be required to unravel these genetic phenomena.

Methods

Editorial policies and ethical considerations

This study obtained ethics approval from the North West Research Ethics Committee (11/NW/0421 and 15/YH/0365). Informed consent was gained from all patients (or their respective parental guardians) prior to ophthalmic examination and genetic testing. The research adhered to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Patient ascertainment and phenotypic data collection

Children (under 16 years of age) with: (i) nystagmus, (ii) at least one other ocular feature of albinism (iris transillumination, foveal hypoplasia, optic nerve misrouting) and (iii) skin pigmentation in keeping with their familial background were retrospectively ascertained through the database of the North West Genomic Laboratory Hub, Manchester, UK. The children were self-reported as unrelated. Only individuals for whom a referral for genetic testing was received between June 2015 and June 2018 (36 months total) were included.

All study participants were examined in tertiary paediatric ophthalmic genetic clinics at Manchester University Hospitals, Manchester, UK. A 3-generation pedigree and full ocular, developmental and medical history were obtained for each patient; this included questioning about skin and hair pigmentation at birth, ability to tan, and ease of burning on sun exposure; eye colour was also noted. Clinical assessment included visual acuity testing using age-appropriate optotypes, dilated fundus examination, cycloplegic refraction and orthoptic assessment; the dermatological phenotype at the time of consultation was also recorded.

Optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging was offered to children aged 4 or more years. The Spectralis HRA + OCT system (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) or the Topcon 3D OCT 2000 (Topcon GB, Newberry, Berkshire, UK) were used. Due to limited compliance and the presence of nystagmus it was possible to obtain reliable scans of the fovea in only 6/12 study subjects.

Electrodiagnostic testing to look for optic nerve misrouting was performed in 10/12 cases. The protocols used incorporated the standards of the International Society for Electrophysiology of Vision (ISCEV) for clinical VEPs41,42; both pattern onset (30’ checks, 200 ms on, 800 ms off) and flash (Grass #4, 1 Hz) stimulation were attempted in all tested subjects. The tests were carried out using either an Espion2 or Espion3 clinical electrophysiology system (Diagnosys LLC, Lowell, MA, USA), with flash stimulation provided by a PS33 photic stimulator (Grass Technologies, Warwick, RI, USA). Misrouting was assessed using an index of crossed asymmetry, looking at the difference between the VEP recorded 3 cm to the right and left of the occipital midline and comparing right and left eye stimulation. Results were graded using the following scale: −1: No response recordable; 0: No crossed asymmetry (right-left scalp difference plots were the same for the right and left eye); +1: Possible crossed asymmetry (wherein most VEP components did not cross, but minor components did); +2: Probable crossed asymmetry (partial crossed asymmetry, where asymmetry is only seen in one eye, or the polarity of the difference plots is opposite but partially out of phase); +3: Definite crossed asymmetry (difference plots are mirror images of each other). An alternative approach is to use the asymmetry index43. However, whereas the asymmetry index utilises a single time slice, our method considers the whole range of the visual response. Notably, we have opted to use this subjective grading technique as opposed to other, more objective approaches that evaluate the whole response (such as Pearson’s correlate44 or the chiasmal coefficient45) for two reasons. Firstly, both Pearson’s correlate44 and the chiasmal coefficient45 do not take data scale into consideration. As a result, when there is no signal, background noise can give an artificially high numeric measure of crossed asymmetry. Secondly, significant but localised optic nerve misrouting may be masked by high positive correlation of the rest of the waveform. In any case, our approach was compared to both Pearson’s correlate and chiasmal coefficient and we found these three methods to be in good agreement.

Clinical genetic testing and bioinformatic analysis

Gene panel testing and analysis were performed at the North West Genomic Laboratory Hub Genomic Diagnostic Laboratory, a UK Accreditation Service Clinical Pathology Accredited medical laboratory (Clinical Pathology Accredited identifier, no. 4015). DNA was extracted from peripheral blood samples and subsequently processed using Agilent SureSelect target-enrichment kits (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA). These were designed to capture all exons and 50 base pairs of flanking introns of 193 genes associated with inherited ophthalmic disease. Analysis was then limited to a panel of clinically relevant genes, chosen by the referring clinician. For our selected partial albinism cases, the panels used for analysis included: an OA/OCA panel consisting of 18 genes (5/12 cases), a nystagmus & foveal hypoplasia panel consisting of 26 genes (encompassing the genes included in the OA/OCA panel; 5/12 cases), an optic nerve disorders panel consisting of 40 genes (encompassing both the OA/OCA and the nystagmus & foveal hypoplasia panel genes; 1/12); a list of all tested transcripts and genes can be found in Supplementary Table S1. One study participant (proband 9) underwent clinical exome sequencing using a specifically designed Agilent SureSelect target-enrichment kit.

A detailed description of our sequencing pipeline and downstream bioinformatics analysis has been previously reported46. Briefly, after enrichment, the samples were sequenced on an Illumina HiSeq. 2000/2500 system (Illumina, Inc, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Sequence reads were subsequently demultiplexed using CASAVA software version 1.8.2 (Illumina, Inc, San Diego, CA) and aligned to the hg19 reference genome using the Burrows Wheeler Aligner (BWA-short version 0.62)47. Duplicate reads were removed using Samtools before base quality score recalibration and insertion-deletion realignment using the Genome Analysis Tool Kit (GATK-lite version 2.0.39)48. The UnifiedGenotyper within the Genome Analysis Tool Kit was used for single nucleotide variant and insertion-deletion discovery49. To reduce the number of false-positive variants, we primarily limited the clinical analysis to changes with sequencing quality metrics above specific criteria: single nucleotide variants with ≥50x independent sequencing reads and ≥45 mean quality value, and insertions-deletions with support from >25% of the aligned and independent sequencing reads were considered46. Copy number variants were detected from high-throughput sequencing read data using ExomeDepth version 1.1.646,50.

Clinical interpretation of variants was broadly consistent with the 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics best practice guidelines51. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor52 was used to predict functional consequences of the identified genetic changes, and a pathogenicity classification score51 was assigned after extensive appraisal of the scientific literature, and the patient’s clinical referral. In silico modelling was also used, utilising PolyPhen-253 and Combined Annotation-Dependent Depletion (CADD)54. A clinical report was then generated and variants that possibly or probably accounted for the tested individual’s clinical presentation were highlighted. Where possible, the samples of relatives were sought to identify zygosity and confirm pathogenicity.

For the purpose of this study, participants were split into 3 groups, as previously described in Taylor et al.55:

Probable molecular diagnosis group: patients with clearly or likely disease-associated variant(s) in an apparently disease-causing state (e.g., ≥1 variant in a gene linked with dominant disease or ≥2 variants in a gene linked with recessive disease).

Possible molecular diagnosis group: cases harboring a single clearly or likely disease-associated variant in a gene linked with recessive disease, provided the patient phenotype matches the known spectrum of clinical features for this gene; it can be speculated that most of these participants will carry a second variant that could not be detected.

Unknown molecular diagnosis group: all other cases for which no clearly or likely disease-associated variants were detected.

Evaluating the prevalence of selected genotypes in an external cohort

After identifying some unexpected combinations of TYR variants in the patient cohort, we aimed to ascertain how frequently these combinations were encountered in individuals without a clinical diagnosis of albinism. We interrogated genomic data from 4046 individuals within the 100,000 genomes pilot dataset25. None of these individuals had features suggestive of albinism. The data were accessed via remote desktop after the relevant participant agreement was signed. The following questions were asked:

How many of the 4046 individuals have the TYR p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] allele in homozygous state?

How many of the 4046 individuals have the TYR p.[(Ser192Tyr);(Arg402Gln)] allele in heterozygous state AND another rare TYR variant?

How many of the 4046 individuals have a rare TYR variant AND a rare OCA2 variant?

To define rare for the purposes of this experiment, we interrogated the gnomAD variant database14 (accessed 23/01/2019) for known disease-associated variants in both OCA2 and TYR. The minor allele frequency (MAF) of the most prevalent OCA2 or TYR mutation was used as cut-off: this corresponded to 0.047, the frequency of the OCA2 c.1441 G > A, (p.Ala481Thr) variant in the gnomAD European Finnish population.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the North West Research Ethics Committee (11/NW/0421 and 15/YH/0365).

Provenance and peer review

Externally peer reviewed.

Supplementary information

Supplementary material for "clinical and genetic variability in children with partial albinism"

Acknowledgements

PIS is supported by the UK National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Lecturer Programme. Other sources of funding include: The Manchester NIHR Biomedical Research Centre (IS-BRC-1215-20007), the NIHR Greater Manchester Clinical Research Network, RP Fighting Blindness and Fight For Sight (RP Genome Project GR586). The funding organizations had no role in the design or conduct of this research.

Author contributions

Contributors Design and conception of study: PIS. Data collection and assembly: P.C., J.E., N.R.A.P., T.F., S.C.R., T.G., G.H., K.S., D.K., E.T., I.C.L., S.D., J.C.S., S.B., J.L.A., G.C.B. and P.I.S. Data analysis and interpretation: P.C., J.E. and P.I.S. Writing of manuscript: PC and PIS. Critical review and revision of manuscript: J.E., N.R.A.P., T.F., S.C.R., T.G., G.H., I.C.L., S.D., J.C.S., S.B., J.L.A., G.C.B. & P.I.S. Submission of manuscript: P.C.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Patrick Campbell and Jamie M. Ellingford.

Contributor Information

Graeme C. M. Black, Email: graeme.black@manchester.ac.uk

Panagiotis I. Sergouniotis, Email: panagiotis.sergouniotis@manchester.ac.uk

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-51768-8.

References

- 1.Montoliu L, et al. Increasing the complexity: new genes and new types of albinism. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:11–18. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Summers CG. Albinism: classification, clinical characteristics, and recent findings. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2009;86:659–662. doi: 10.1097/OPX.0b013e3181a5254c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Norman CS, et al. Identification of a functionally significant tri-allelic genotype in the Tyrosinase gene (TYR) causing hypomorphic oculocutaneous albinism (OCA1B) Sci. Rep. 2017;7:4415. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-04401-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCafferty BK, et al. Clinical Insights Into Foveal Morphology in Albinism. J. Pediatr. Ophthalmol. Strabismus. 2015;52:167–172. doi: 10.3928/01913913-20150427-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tarpey P, et al. Mutations in FRMD7, a newly identified member of the FERM family, cause X-linked idiopathic congenital nystagmus. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1242–1244. doi: 10.1038/ng1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Poulter JA, et al. Recessive mutations in SLC38A8 cause foveal hypoplasia and optic nerve misrouting without albinism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013;93:1143–1150. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hingorani M, Williamson KA, Moore AT, van Heyningen V. Detailed ophthalmologic evaluation of 43 individuals with PAX6 mutations. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009;50:2581–2590. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kruijt, C. C. et al. The Phenotypic Spectrum of Albinism. Ophthalmology, 10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.08.003 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Newman WG, Black GC. Delivery of a clinical genomics service. Genes. 2014;5:1001–1017. doi: 10.3390/genes5041001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lasseaux E, et al. Molecular characterization of a series of 990 index patients with albinism. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018;31:466–474. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagirdar K, et al. Molecular analysis of common polymorphisms within the human Tyrosinase locus and genetic association with pigmentation traits. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:552–564. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Apkarian, P. & Bour, L. J. Aberrant albino and achiasmat visual pathways: noninvasive electrophysiological assessment. Principles and practice of clinical electrophysiology of vision. MIT Press, Cambridge 369–411 (2006).

- 13.Neveu MM, Jeffery G, Burton LC, Sloper JJ, Holder GE. Age-related changes in the dynamics of human albino visual pathways. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2003;18:1939–1949. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lek M, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han R, et al. GPR143 Gene Mutations in Five Chinese Families with X-linked Congenital Nystagmus. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:12031. doi: 10.1038/srep12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez Y, et al. Isolated foveal hypoplasia with secondary nystagmus and low vision is associated with a homozygous SLC38A8 mutation. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2014;22:703–706. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toral MA, et al. Structural modeling of a novel mutation that causes foveal hypoplasia. Mol Genet Genomic Med. 2017;5:202–209. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giebel LB, et al. Tyrosinase gene mutations associated with type IB (‘yellow’) oculocutaneous albinism. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1991;48:1159–1167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.King RA, et al. Tyrosinase gene mutations in oculocutaneous albinism 1 (OCA1): definition of the phenotype. Hum. Genet. 2003;113:502–513. doi: 10.1007/s00439-003-0998-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee ST, et al. Mutations of the P gene in oculocutaneous albinism, ocular albinism, and Prader-Willi syndrome plus albinism. N. Engl. J. Med. 1994;330:529–534. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402243300803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marti A, et al. Lessons of a day hospital: Comprehensive assessment of patients with albinism in a European setting. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2018;31:318–329. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yuasa I, et al. OCA2 481Thr, a hypofunctional allele in pigmentation, is characteristic of northeastern Asian populations. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;52:690–693. doi: 10.1007/s10038-007-0167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Landrum MJ, et al. ClinVar: public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:D980–5. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saitoh S, Oiso N, Wada T, Narazaki O, Fukai K. Oculocutaneous albinism type 2 with a P gene missense mutation in a patient with Angelman syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2000;37:392–394. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.5.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caulfield, M. et al. The 100,000 Genomes Project Protocol, 10.6084/M9.FIGSHARE.4530893.V2 (2017).

- 26.Grønskov K, et al. A pathogenic haplotype, common in Europeans, causes autosomal recessive albinism and uncovers missing heritability in OCA1. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:645. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-37272-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hudjashov G, Villems R, Kivisild T. Global patterns of diversity and selection in human tyrosinase gene. PLoS One. 2013;8:e74307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0074307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stokowski RP, et al. A Genomewide Association Study of Skin Pigmentation in a South Asian Population. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81:1119–1132. doi: 10.1086/522235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nan H, Kraft P, Hunter DJ, Han J. Genetic variants in pigmentation genes, pigmentary phenotypes, and risk of skin cancer in Caucasians. Int. J. Cancer. 2009;125:909–917. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zernant J, et al. Frequent hypomorphic alleles account for a significant fraction of ABCA4 disease and distinguish it from age-related macular degeneration. J. Med. Genet. 2017;54:404–412. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2017-104540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan DM, et al. Identification of cis-suppression of human disease mutations by comparative genomics. Nature. 2015;524:225–229. doi: 10.1038/nature14497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oh J, et al. Positional cloning of a gene for Hermansky–Pudlak syndrome, a disorder of cytoplasmic organelles. Nat. Genet. 1996;14:300–306. doi: 10.1038/ng1196-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ammann S, et al. Mutations in AP3D1 associated with immunodeficiency and seizures define a new type of Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome. Blood. 2016;127:997–1006. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-09-671636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simeonov DR, et al. DNA variations in oculocutaneous albinism: an updated mutation list and current outstanding issues in molecular diagnostics. Hum. Mutat. 2013;34:827–835. doi: 10.1002/humu.22315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wei A-H, Yang X-M, Lian S, Li W. Genetic analyses of Chinese patients with digenic oculocutaneous albinism. Chin. Med. J. 2013;126:226–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gazzo A, et al. Understanding mutational effects in digenic diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:e140. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D’Mello, S. A. N., Finlay, G. J., Baguley, B. C. & Askarian-Amiri, M. E. Signaling Pathways in Melanogenesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 17 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Wollstein A, et al. Novel quantitative pigmentation phenotyping enhances genetic association, epistasis, and prediction of human eye colour. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:43359. doi: 10.1038/srep43359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.George A, et al. Biallelic Mutations in MITF Cause Coloboma, Osteopetrosis, Microphthalmia, Macrocephaly, Albinism, and Deafness. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;99:1388–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Young A, et al. GNAI3: Another Candidate Gene to Screen in Persons with Ocular Albinism. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162273. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Odom JV, et al. ISCEV standard for clinical visual evoked potentials: (2016 update) Doc. Ophthalmol. 2016;133:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10633-016-9553-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robson AG, et al. ISCEV guide to visual electrodiagnostic procedures. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2018;136:1–26. doi: 10.1007/s10633-017-9621-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Apkarian P. A practical approach to albino diagnosis. VEP misrouting across the age span. Ophthalmic Paediatr. Genet. 1992;13:77–88. doi: 10.3109/13816819209087608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Soong F, Levin AV, Westall CA. Comparison of techniques for detecting visually evoked potential asymmetry in albinism. J. AAPOS. 2000;4:302–310. doi: 10.1067/mpa.2000.107901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pott JWR, Jansonius NM, Kooijman AC. Chiasmal coefficient of flash and pattern visual evoked potentials for detection of chiasmal misrouting in albinism. Doc. Ophthalmol. 2003;106:137–143. doi: 10.1023/A:1022526409674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ellingford JM, et al. Molecular findings from 537 individuals with inherited retinal disease. J. Med. Genet. 2016;53:761–767. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2016-103837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McKenna A, et al. The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res. 2010;20:1297–1303. doi: 10.1101/gr.107524.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van der Auwera GA, et al. From FastQ data to high confidence variant calls: the Genome Analysis Toolkit best practices pipeline. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2013;43:11.10.1–33. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1110s43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Plagnol V, et al. A robust model for read count data in exome sequencing experiments and implications for copy number variant calling. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:2747–2754. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McLaren W, et al. The Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor. Genome Biol. 2016;17:122. doi: 10.1186/s13059-016-0974-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adzhubei I, Jordan DM, Sunyaev SR. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. 2013;Chapter 7:Unit7.20. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kircher M, et al. A general framework for estimating the relative pathogenicity of human genetic variants. Nat. Genet. 2014;46:310–315. doi: 10.1038/ng.2892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Taylor RL, et al. Panel-Based Clinical Genetic Testing in 85 Children with Inherited Retinal Disease. Ophthalmology. 2017;124:985–991. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2017.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for "clinical and genetic variability in children with partial albinism"