Abstract

Bison (Bison bison) are one of the few terrestrial megafauna to survive the transition into the Holocene and provide a unique opportunity to study a species on a broad spatiotemporal scale. Today, bison are primarily managed in small and isolated herds with little known about their ancestral ecology. We studied the carbon and nitrogen isotopes of Northern Great Plains bison from the terminal Pleistocene and throughout the Holocene to gain insight into their paleoecology. This time span is contemporary with the first population bottleneck experienced by bison at the end of the Pleistocene and includes the second bottleneck which occurred in the late 19th century. Results were compared with modern bison herd isotopic values from Theodore Roosevelt National Park (TRNP). Patterns of isotopic variation found in bison over time indicate significant (δ13C p = 0.0008, δ15N p = 0.002) differences in diet composition and correlate with climate throughout the Holocene. Isotopic relationships described here reveal the plasticity of ancient bison in unrestricted rangelands during periods of climatic fluctuations. Managers at TRNP and elsewhere should pursue opportunities to expand bison range to maximize forage opportunities for the species in the face of future environmental change.

Subject terms: Conservation biology, Palaeoecology, Stable isotope analysis, Palaeoecology

Introduction

The transition from the Pleistocene into the Holocene epoch (~11.7 thousand years ago) marked the disappearance of many North American megafauna. As this mass extinction event is more thoroughly investigated it has become clear that the cause cannot be attributed to any singular explanation for all species or regions1–4. Bison (Bison bison) are one of the few terrestrial megafauna to survive the late Pleistocene extinction in North America. Because of their longevity on the landscape and widespread historical range, they provide a unique opportunity for species study across broad temporal and spatial scales.

Bison entered North America from Eurasia via the Bering Land Bridge during two separate windows of time (195 to 135 thousand years ago and 45 to 21 thousand years ago) when the area’s ice sheets retreated and the exposed ground was above sea level5. They rapidly colonized lower latitudes of North America when an ice-free corridor between the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets opened around 14 to 13.5 thousand years ago2,6. In North America, the stable climate during interglaciation led to the rapid spreading of peatlands and dense forests, limiting connectivity of suitable habitat and the ability of megafauna to disperse when coping with climate change2,7. This issue was confounded by rising sea levels that flooded former dispersal corridors2,4. Fossil records show that animal populations were dwindling before evidence of human presence even though some researchers have attributed the loss of Pleistocene megafauna at least in part to human activity2,4.

Ancient DNA data reveal that bison experienced a drastic reduction in numbers during the terminal Pleistocene, resulting in a genetic bottleneck8,9. Subsequently, they successfully repopulated North America in the tens of millions by the Early Holocene, spanning from Alaska to Mexico6,9. Near the end of the 19th century, bison suffered a second bottleneck when they were reduced to a few hundred individuals as a result of European settlement of the continent9,10. Through conservation efforts enacted during the last century, North American bison have been brought back from the brink of extinction, but their long-term viability as a species remains threatened due to restricted rangelands, artificial selection within confined herds, and a lack of gene flow between herds. Questions remain about the genetic diversity currently found in conservation herds and how the species will respond to environmental change within restricted areas. Analysis of stable isotopes in bison remains may help shed light on bison diet and foraging habitat selection over time, providing insights regarding physiological plasticity of the species relevant to management.

Isotopic biogeochemistry of collagen found in ancient bones and teeth is increasingly used in the construction of paleoecology and paleoenvironments. In addition to recording climatic variables such as temperature and precipitation, stable isotopic signatures encapsulate feeding strategies of animals from the past11–13. Isotopic ratios of carbon (δ13C) and nitrogen (δ15N) are assimilated into herbivore skeletal collagen and tooth dentin through diet, recording the isotopic composition of plant material consumed14. These values will remain the same over time in well-preserved specimens15. Bone collagen has a slow turnover rate and will record several years of the animal’s life16–18. Tooth dentin forms at a specific point in development and records a shorter window of time, in the order of months19,20. The carbon isotopic signature depends on the proportion of plants having C3 and C4 photosynthetic pathways in ecosystems21,22 as well as changes in atmospheric CO2 from canopy cover in forested areas23 or post-industrial revolution CO2 emissions13. The values of C3 plants in North America range from −30 to −24‰ and C4 plants fall between −15 and −11‰24. This allows us to distinguish between grazers, browsers, and mixed feeders due to the depletion in 13C (i.e. lower δ13C values) observed in grazing diets17. Bison exhibit an enrichment factor of 6.3‰25 when carbon isotopes are assimilated into their skeletal tissue and this value needs to be factored into calculating the percentage of C3 and C4 plants in bison diet. Therefore, the expected δ13C values of bison feeding primarily on C3 plants would be between −23.7 and −17.7‰, while C4 bison diets would range from −8.7 and −4.7‰. Throughout the Holocene, the Great Plains have been largely dominated by Poaceae (grass) communities26, which can exhibit C3 or C4 photosynthetic pathways. The climate in the Northern Great Plains has predominately favored the C3 subfamily Pooideae with a smaller amount of C4 subfamilies, Panicoideae and Chloridoideae. The abundance of C4 grasses increases as warm seasons get longer, allowing us to capture climatic changes in the diets of grazers22. Nitrogen isotopic values provide insight into moisture level and nutritional stress due to an observed increase in δ15N in animal tissue from the recycling of urea under conditions of drought15,17,27,28. However, there are other factors that contribute to nitrogen values in herbivores. Higher nitrogen can indicate warmer temperatures and a diet composed of more graminoids and herbs than trees and shrubs13,29–32. In modern European bison, it was found that canopy cover had the biggest influence on δ15N, where less light will decrease nitrogen values in plants29.

North American isotopic studies of bison to date have primarily focused on Pleistocene paleoecology30,31,33–36, climatic interpretations11,32, and values from modern herds12,27,37. At present, there are few isotopic studies of Holocene bison in North America. Existing research covers relatively short time periods or small sample sizes11,38–41. The limited data on North American bison from the Holocene may be in part due to the prior perception of a relatively stable climate during this epoch, though the most recent studies of paleoclimate portray the Holocene as a dynamic period with fluctuations in temperature and precipitation42–44. An analysis of approximately fifty paleoclimatic records of greenhouse gases, glacial coverage, and pollen profiles determined that the Holocene had several periods of sudden climate change outlined by variations in atmospheric circulation, moisture, and temperature changes43. For instance, a study of pollen records found three periods in which climate rapidly heated during the Holocene43 and evidence of a steep drop in temperature at ~8.2 thousand years ago as well as other large fluctuations in temperature throughout the Holocene are supported by the analysis of Greenland ice cores44. Therefore, bison in North America during the Holocene had to adapt to a wider range of climatic conditions than previously thought. The amount of variation seen in bison isotopic values throughout specific time periods provides insight into their use of different resources as the environment changed39,40.

The above-described wealth of information available on Holocene and Pleistocene isotope variation provides a unique opportunity to better understand historic bison through analysis of their bones and teeth represented in archaeological and natural history collections in the Northern Great Plains. Here, we explore a subset of that history through analysis of bison specimens from 22 archaeological sites across the Northern Great Plains spanning the Late Pleistocene to the Late Holocene in comparison to extant bison from Theodore Roosevelt National Park (TRNP), North Dakota, USA (Fig. 1). Our objectives are to: 1) identify δ13C and δ15N variation indicative of environmental change across time, and 2) utilize isotopic signatures to elucidate feeding ecology of historic bison in context of modern counterparts in North Dakota. We expect that isotopic values in bison will follow changes in climate and subsequently, isotope values of plant material. We expect increased δ13C and δ15N during periods of warm and dry conditions22.

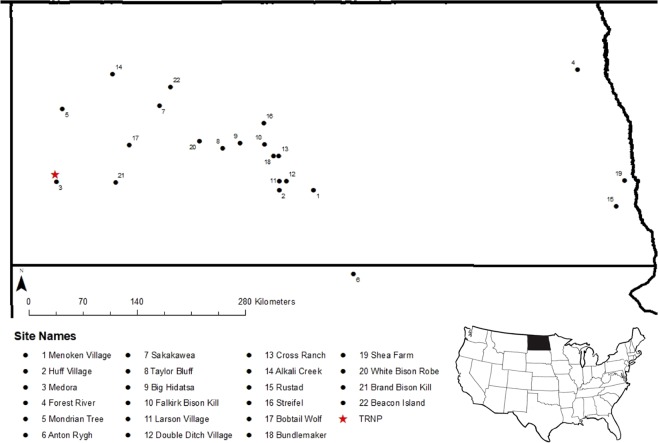

Figure 1.

Locations of sample sites within North Dakota and South Dakota, USA. Black circles indicate archaeological sites and a red star identifies the modern bison sample site, Theodore Roosevelt National Park (TRNP). Map layer sourced from: Esri, derived from Tomtom North America, Inc. “U.S. State Boundaries, North Dakota” [downloaded file]. Scale 1:4,750,000. “USA State Boundaries”. URL: https://www.arcgis.com/home/item.html?id = 540003aa59b047d7a1f465f7b1df1950. (September 9, 2019). This map was created using ArcGIS® software version 10.6 by Esri (www.esri.com).

Results

Fifty-five of the fifty-nine samples of ancient bison bones and teeth yielded sufficient collagen (>1%) to produce reliable data. All samples included in the analysis have C:N ratios between 2.9 and 3.6, relative carbon (%C) >30%, and relative nitrogen (%N) between 11 and 16%, indicative of well-preserved collagen (Table 1)45,46. Five modern bison tooth samples (Bison 100–Bison 104) from TRNP herds returned carbon and nitrogen isotopic ratios for comparison with ancient samples.

Table 1.

Bison sample description including archaeological sites, skeletal component, age in cal BP, and diagnostics for well-preserved collagen isotopic values.

| Bison | Sample Site | Skeletal Component | Cal BP Date Range | Median Age (cal BP) | % Collagen | % C | % N | C:N | δ13C (‰ VPDB) | δ15N (‰ AIR) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Medora | molar fragment | 270 | 12 | 112 | 4.4 | 45.0 | 16.3 | 3.2 | −17.4 | 6.2 |

| 2 | Mondrian Tree 32MZ58 | bone fragment | 3357 | 3241 | 3291 | 4.5 | 46.9 | 16.0 | 3.4 | −21.1 | 8.1 |

| 3 | Mondrian Tree 32MZ58 | phalanx | 2724 | 2497 | 2580 | 3.0 | 42.6 | 14.9 | 3.3 | −18.5 | 4.9 |

| 4 | Anton Rygh 39CA4 | metatarsal | 501 | 332 | 469 | 6.3 | 42.9 | 15.1 | 3.3 | −14.8 | 5.8 |

| 5 | Anton Rygh 39CA4 | carpal | 481 | 318 | 388 | 5.3 | 45.6 | 16.7 | 3.2 | −17.5 | 5.7 |

| 6 | Menoken Village 32BL2 | phalanx | 910 | 787 | 863 | 2.6 | 45.9 | 16.3 | 3.3 | −19.1 | 6.4 |

| 10 | White Bison Robe 32ME7 | molar fragment | 679 | 571 | 665 | 2.5 | 44.4 | 16.5 | 3.1 | −17.8 | 6.8 |

| 11 | White Bison Robe 32ME7 | molar | 460 | 313 | 381 | 4.7 | 45.9 | 17.0 | 3.2 | −17.8 | 6.6 |

| 12 | Huff Village 32MO11 | molar fragment | 527 | 501 | 513 | 5.0 | 46.0 | 16.8 | 3.2 | −19.3 | 6.0 |

| 13 | Huff Village 32MO11 | M3 | 518 | 487 | 504 | 9.9 | 41.6 | 15.3 | 3.2 | −18.6 | 6.5 |

| 14 | Alkali Creek 32DU336 | premolar | 1529 | 1412 | 1466 | 3.0 | 39.8 | 14.5 | 3.2 | −18.3 | 6.9 |

| 18 | Sakakawea 32ME11 | M3 | 302 | 7 | 166 | 5.4 | 46.4 | 16.7 | 3.2 | −18.8 | 6.3 |

| 20 | Rustad Site 32R1775 | molar fragment | 8176 | 8041 | 8107 | 1.4 | 40.2 | 14.3 | 3.3 | −16.3 | 9.3 |

| 22 | Streifel Site 32ML903 | head of femur | 7834 | 7701 | 7768 | 3.8 | 41.9 | 15.0 | 3.3 | −14.6 | 5.0 |

| 25 | Big Hidatsa 32ME12 | molar | 294 | 14 | 167 | 5.9 | 45.4 | 16.5 | 3.2 | −18.6 | 7.4 |

| 26 | Big Hidatsa 32ME12 | M3 | 290 | 14 | 170 | 4.3 | 44.0 | 16.4 | 3.1 | −20.5 | 7.5 |

| 29 | Falkirk Bison Kill 32ML927 | vertebrae | 694 | 661 | 677 | 8.2 | 43.1 | 14.9 | 3.4 | −15.6 | 5.8 |

| 30 | Falkirk Bison Kill 32ML927 | molar | 309 | 156 | 296 | 3.5 | 44.9 | 16.7 | 3.1 | −16.3 | 6.4 |

| 31 | Bobtail Wolf 32DU955A | phalanx | 283 | 5 | 189 | 6.2 | 44.9 | 15.6 | 3.4 | −20.1 | 6.1 |

| 32 | Larson Village 32BL9 | M3 | 491 | 320 | 437 | 3.8 | 45.3 | 16.9 | 3.1 | −17.1 | 5.5 |

| 33 | Larson Village 32BL9 | metatarsal | 485 | 319 | 429 | 5.4 | 43.9 | 16.0 | 3.2 | −20.3 | 7.3 |

| 34 | Double Ditch Village 32BL8 | molar fragment | 465 | 315 | 379 | 2.5 | 44.2 | 16.5 | 3.1 | −15.1 | 5.0 |

| 35 | Bundlemaker 32OL159 | molar | 1173 | 979 | 1027 | 6.2 | 42.3 | 15.2 | 3.2 | −16.7 | 6.6 |

| 36 | Cross Ranch 32OL151 | M3 | 1175 | 1010 | 1107 | 5.0 | 44.2 | 16.1 | 3.2 | −17.2 | 6.4 |

| 37 | Taylor Bluff 32ME366 | phalanx | 272 | 11 | 125 | 6.2 | 42.3 | 15.2 | 3.2 | −18.2 | 5.8 |

| 38 | Taylor Bluff 32ME366 | molar fragment | 294 | 14 | 167 | 3.6 | 44.8 | 16.4 | 3.2 | −20.1 | 7.0 |

| 39 | Falkirk Bison Kill 32ML927 | molar fragment | 673 | 566 | 656 | 1.5 | 40.4 | 14.3 | 3.3 | −19.4 | 8.3 |

| 40 | Shea Farm 32CS101 | premolar root | 527 | 492 | 509 | 5.2 | 43.0 | 15.6 | 3.2 | −16.5 | 5.5 |

| 41 | White Bison Robe 32ME7 | M3 | 465 | 315 | 379 | 3.6 | 44.7 | 16.5 | 3.2 | −19.6 | 8.3 |

| 42 | White Bison Robe 32ME7 | M3 | 458 | 307 | 386 | 6.3 | 42.3 | 15.5 | 3.2 | −20.3 | 8.0 |

| 43 | Menoken Village 32BL2 | molar fragment | 1175 | 989 | 1077 | 9.7 | 41.9 | 15.3 | 3.2 | −15.4 | 6.2 |

| 44 | Brand Bison Kill 32SK201 | atlas | 703 | 668 | 683 | 3.5 | 45.8 | 16.5 | 3.2 | −19.7 | 6.2 |

| 45 | Brand Bison Kill 32SK201 | atlas | 688 | 665 | 675 | 2.5 | 44.8 | 16.0 | 3.3 | −20.3 | 7.5 |

| 46 | Forest River | molar fragment | 284 | 22 | 185 | 3.7 | 44.9 | 16.4 | 3.2 | −17.8 | 6.0 |

| 47 | Falkirk Bison Kill 32ML927 | molar fragment | 670 | 565 | 653 | 2.8 | 45.4 | 16.3 | 3.3 | −20.2 | 6.9 |

| 48 | Rustad Site 32R1775 | molar | 7972 | 7860 | 7936 | 7.2 | 43.6 | 15.8 | 3.2 | −17.9 | 8.8 |

| 49 | Alkali Creek 32DU336 | molar | 2750 | 2539 | 2728 | 5.0 | 42.6 | 15.8 | 3.2 | −18.3 | 7.8 |

| 50 | Rustad Site 32R1775 | mandible | 9029 | 8786 | 8999 | 2.1 | 42.0 | 15.0 | 3.3 | −18.2 | 6.6 |

| 51 | Mondrian Tree 32MZ58 | M3 | 631 | 516 | 544 | 12.0 | 42.5 | 15.6 | 3.2 | −19.8 | 6.8 |

| 52 | Alkali Creek 32DU336 | premolar root | 1567 | 1416 | 1533 | 5.7 | 43.0 | 16.0 | 3.1 | −20.3 | 7.3 |

| 53 | Streifel Site 32ML903 | bone fragment | 4079 | 3897 | 3964 | 11.3 | 42.0 | 15.4 | 3.2 | −20.3 | 7.0 |

| 54 | Beacon Island 32MN234 | molar fragment | 12389 | 12030 | 12209 | 1.0 | 37.5 | 13.0 | 3.4 | −21.5 | 6.2 |

| 55 | Streifel Site 32ML903 | metatarsal | 4082 | 3892 | 3966 | 12.6 | 42.0 | 15.5 | 3.2 | −19.1 | 6.3 |

| 56 | Mondrian Tree 32MZ58 | bone fragment | 2744 | 2502 | 2701 | 9.3 | 42.6 | 15.3 | 3.2 | −19.1 | 7.8 |

| 57 | Mondrian Tree 32MZ58 | phalanx | 2744 | 2497 | 2622 | 6.2 | 41.6 | 15.0 | 3.2 | −19.8 | 5.8 |

| 58 | Beacon Island 32MN234 | molar | na | na | na | <1 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 59 | Beacon Island 32MN234 | molar | 12396 | 12056 | 12229 | 3.7 | 41.7 | 14.9 | 3.3 | −21.1 | 5.0 |

| 60 | Beacon Island 32MN234 | molar | 12373 | 11845 | 12068 | 2.0 | 41.9 | 15.0 | 3.3 | −21.2 | 5.7 |

| 61 | Beacon Island 32MN234 | molar | na | na | na | <1 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 62 | Beacon Island 32MN234 | M3 | 12547 | 12140 | 12431 | 4.2 | 41.4 | 15.2 | 3.2 | −18.4 | 5.9 |

| 63 | Beacon Island 32MN234 | molar | na | na | na | <1 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 64 | Mondrian Tree 32MZ58 | phalanx | 3825 | 3640 | 3705 | 5.6 | 40.3 | 14.3 | 3.3 | −20.7 | 8.1 |

| 65 | Brand Bison Kill 32SK201 | horncore | 691 | 661 | 675 | 8.7 | 45.6 | 16.7 | 3.2 | −18.8 | 7.5 |

| 66 | Rustad Site 32R1775 | molar | 8191 | 8042 | 8116 | 3.8 | 41.7 | 14.9 | 3.3 | −16.2 | 8.1 |

| 67 | Rustad Site 32R1775 | M3 | 8178 | 8036 | 8107 | 5.1 | 40.5 | 14.7 | 3.2 | −17.5 | 6.8 |

| 68 | Rustad Site 32R1775 | molar | 8187 | 8042 | 8116 | 5.0 | 41.5 | 14.9 | 3.3 | −16.2 | 7.8 |

| 97 | Streifel Site 32ML903 | phalanx | 4984 | 3998 | 3913 | 10.5 | 42.4 | 15.2 | 3.3 | −19.3 | 6.5 |

| 98 | Streifel Site 32ML903 | bone fragment | 7932 | 7793 | 7862 | 3.8 | 42.3 | 14.9 | 3.3 | −19.1 | 8.5 |

| 99 | Streifel Site 32ML903 | phalanx | na | na | na | <1 | na | na | na | na | na |

| 100 | TRNP (bull) | M3 | na | na | modern | 13.3 | 42.4 | 15.6 | 3.2 | −21.2 | 5.0 |

| 101 | TRNP (bull) | molar | na | na | modern | 16.9 | 42.9 | 15.5 | 3.2 | −20.1 | 5.2 |

| 102 | TRNP (cow) | M3 | na | na | modern | 17.4 | 41.9 | 15.1 | 3.2 | −20.7 | 4.6 |

| 103 | TRNP (cow) | M3 | na | na | modern | 15.8 | 42.7 | 15.6 | 3.2 | −20.0 | 5.0 |

| 104 | TRNP (cow) | molar | na | na | modern | 20.4 | 42.3 | 15.5 | 3.2 | −20.8 | 4.7 |

We determined that the age of ancient bison specimens range from the Late Pleistocene to the Late Holocene, 12,344 to 104 calibrated years before present (cal BP) with samples from the Late Pleistocene (~12.5 cal BP, n = 4), Early Holocene (11,700–8,200 cal BP, n = 1), Middle Holocene (8,200–4,200 cal BP, n = 7), and Late Holocene (4,200–100 cal BP, n = 43) (Table 2)47.

Table 2.

Summary statistics and %C4 plants for bison bones and teeth within each episode.

| Episode (cal BP) | Tissue | n | Mean δ13C ‰ | SD δ13C ‰ | δ13C ‰ | Mean δ15N ‰ | SD δ15N ‰ | δ15N ‰ | % C4 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| low | high | low | high | ||||||||

| Modern | Dentin | 5 | −20.5 | 0.47 | −21.1 | −20.0 | 4.9 | 0.24 | 4.6 | 5.2 | 0 |

| Late Holocene (4,200 – 100) | Dentin | 25 | −18.3 | 1.57 | −20.5 | −15.1 | 6.7 | 0.85 | 5.0 | 8.3 | 14 |

| Bone | 18 | −19.0 | 1.67 | −21.1 | −14.8 | 6.6 | 0.94 | 4.9 | 8.1 | 9 | |

| Middle Holocene (8,200 – 4,200) | Dentin | 5 | −16.8 | 0.82 | −17.9 | −16.2 | 8.2 | 0.96 | 6.8 | 9.3 | 24 |

| Bone | 2 | −16.9 | 3.18 | −19.1 | −14.6 | 6.8 | 2.47 | 5.0 | 8.5 | 24 | |

| Early Holocene (11,700 – 8,200) | Bone | 1 | −18.2 | na | −18.2 | −18.2 | 6.6 | na | 6.6 | 6.6 | 14 |

| Late Pleistocene (12,500 – 11,700) | Dentin | 4 | −20.6 | 1.44 | −21.5 | −18.4 | 5.7 | 0.51 | 5.0 | 6.2 | 0 |

As previously stated, dentin and bone collagen represent different lengths of time in the bison’s life. The sampling method in this study for dentin likely captures less than a year20 while the collagen from bone samples describes the average over several years of the animal’s diet16–18. To compare the variation found in each tissue type, we conducted t-tests for the dentin and bone samples as a whole and also separated into temporal groups. We found no significant differences in the means or variation found in sample tissue types (Supplementary Figure S1), therefore, they are treated functionally the same for the purpose of this paper.

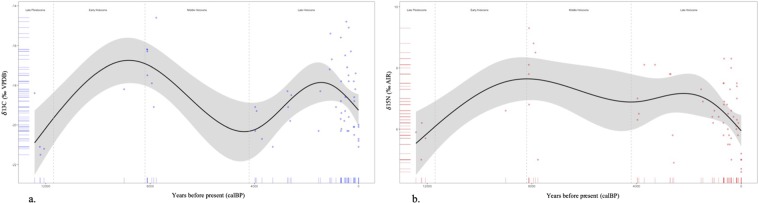

Generalized additive models (GAMs) identified significant changes in bison δ13C (y = −18.42, p = 0.0008) and δ15N (y = 6.49, p = 0.002) values over time (Fig. 2). Model fit values are included in Supplementary Table S2. Bison dentin δ13C values ranged from −21.5 to −15.1‰ and dentin δ15N ranged from 4.6 to 9.3‰. Bison bone δ13C values ranged from −21.1 to −14.6‰ and bone δ15N ranged from 4.9 to 8.5‰ (Table 2). Overall, we observed considerable variability among temporal episodes for isotope values δ13C and δ15N (Table 2, Figs 3, 4). Only one data point is categorized into the Early Holocene, however GAM models visualize the increase in bison’s carbon and nitrogen isotopic values throughout this sub-epoch (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Estimated trendline of isotopic values over time for (a) carbon and (b) nitrogen. Smoothed functions were determined using generalized additive models with shaded areas representing 95% confidence intervals and points representing the data points. Dashed lines separate sub-epoch boundaries; Late Pleistocene – Early Holocene (11,700 ya), Early Holocene – Middle Holocene (8,200 ya), and Middle Holocene – Late Holocene (4,200 ya). Stable isotope measurements were determined on amino acid hydrolysate samples.

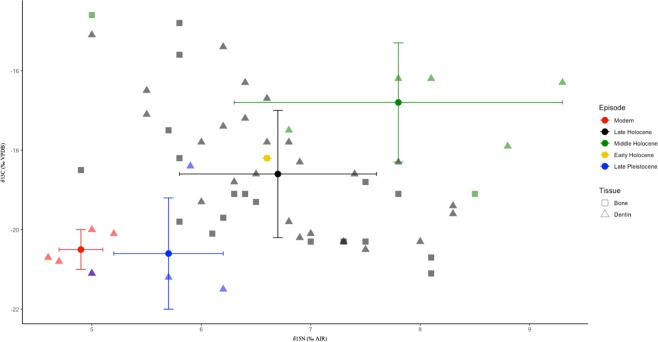

Figure 3.

Plot of δ13C and δ15N values for bison by temporal episode. Bone samples are represented by squares and dentin samples are labeled with triangles. Means and standard deviations are plotted for temporal episodes. Stable isotope measurements were determined on amino acid hydrolysate samples.

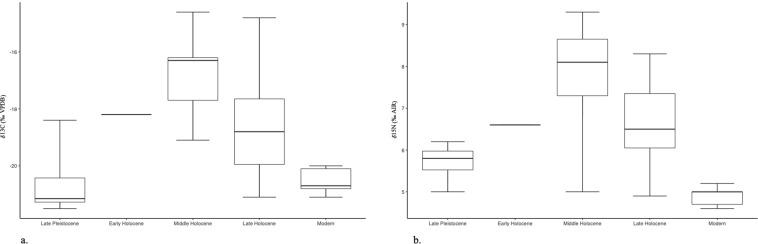

Figure 4.

Box plots of (a) δ13C and (b) δ15N values measured for Late Pleistocene, Early Holocene, Middle Holocene, Late Holocene, and Modern bison. Boxes show the median and upper and lower quartiles while the whiskers show the range of values. Stable isotope measurements were determined on amino acid hydrolysate samples.

Modern bison had the least variation in carbon and nitrogen values and the lowest mean δ15N value, 4.9‰. The highest variation for both isotopes was seen in Middle Holocene bone samples. The highest mean δ13C and δ15N values, −16.8‰ and 8.2‰ respectively, were observed in Middle Holocene bison dentin. Late Pleistocene and modern bison dentin were the most depleted in 13C with a mean δ13C of −20.6‰ and −20.5‰, respectively (Table 2, Figs 3, 4).

Ratios of C3:C4 plants demonstrated that bison diet for each temporal episode predominately included C3 plants (Table 2). Late Pleistocene bison consumed entirely C3 vegetation with an increase in the consumption of C4 plants in the Early Holocene, a peak abundance of C4 material in the Middle Holocene and a small decrease again in the Late Holocene (Table 2, Fig. 2a). Modern bison in TRNP exhibited an entirely C3 diet, congruent with the vegetation found in the park48.

Discussion

This study uses the archaeological record of bison in the Northern Plains to understand their evolutionary responses to environmental change and provide insight for best practices in bison conservation and management. Our analysis of isotopic values from bison remains spans the terminal phase of the Late Pleistocene to present, representing post-glacial changes in bison diet and vegetation associated with changing climate during the recent natural history of the species. The sample assemblage is contemporary with two bison population bottlenecks. The first bottleneck occurred during the terminal Pleistocene and the second in the late 19th century when bison were nearly extirpated by humans6,9.

The Late Pleistocene in the Northern Great Plains is described as a time of sudden environmental change and a significantly wetter landscape after the recent retreat of the Laurentide ice sheet49. Pollen records from the study region indicate an abundance of Picea (evergreen) species and relatively low amounts of herbaceous plants (grasses and forbs)49,50. Late Pleistocene bison samples in the current study are derived from Beacon Island, a Paleoindian kill site in the Agate basin (Fig. 1). The concurrent stratigraphic layer at this site exhibits C3 dominated plant material51 and is congruent with the 100% C3 diet recorded in the δ13C of bison remains (Table 2). However, bison δ15N values from the Late Pleistocene appear surprisingly low considering environmental conditions in the Late Pleistocene were adverse enough to wipe out the majority of megafaunal species and facilitate bison’s first recorded population bottleneck2,8. Though low nitrogen values could be explained by a heavier dependence on nitrogen poor browse material in bison diet17. Substantial incorporation of browse is reported by other Late Pleistocene bison paleoecology studies in North America based on stable isotopes and bison dentition wearing patterns33,52. Additionally, more canopy cover from prominent evergreens would lower the abundance of nitrogen in plant material consumed29. However, we cannot ignore that this could also be an effect of small sample size from only bison dentin for this temporal period.

Evergreen forests south of the Laurentide ice sheet were rapidly succeeded by other vegetative communities in the transition between the Pleistocene and the Holocene49,53,54. By the Early Holocene, new deciduous forest south of the evergreens formed and bordered along riparian areas while grasslands spread throughout the open landscape54. As the Great Plains quickly became dominated by prairie49,54 bison migrated northward into the developing terrain and became plentiful at this time53. Yet only one data point from our sample assemblage falls within the Early Holocene boundaries. This single bison indicates an increase in C4 vegetation incorporated into diet (Table 2), consistent with rising temperatures and the presence of more C4 Chloridoideae grasses51,55. Additional evidence of an increase in C4 grasses are recorded in bison living during the Early Holocene within present day Yellowstone National Park and the state of Nebraska40,56. Nitrogen levels are higher than in Late Pleistocene bison despite an increase in effective moisture in the Early Holocene55, further supporting the idea that bison selected more browse material from low light areas in evergreen forests during the Late Pleistocene.

The Middle Holocene climate is summarized as highly variable with an overall shift towards warmer, drier conditions and patchiness of resources1. Herbaceous plants fluctuated throughout the Middle Holocene, alternating between Poaceae and Ambrosia (ragweed) communities, indicating frequent changes in precipitation50,57. Bison from this sub-epoch exhibit the highest mean values for carbon and nitrogen as well as large variation in bone samples (Table 2, Figs 3, 4). Although the two bone samples from the Middle Holocene (Bison 22 and 98) coincide in both time and space, they exhibit large isotopic differences (Table 1, Figs 1, 3). This could be representative of the vastly fluctuating climate or a remnant of different feeding strategies among bison sexes37. In any case, we observe the greatest amount of C4 vegetation in bison diet at this time for both tissue types (24%), indicating a trend towards longer and warmer growing seasons39. This is corroborated by bison isotopic values from the Eastern Great Plains during the Middle Holocene11.

Climatic conditions in the Northern Great Plains during the Late Holocene generally followed a cooling trend with increasing moisture up to modern day26,55. However, climate proxies provide evidence that severe arid conditions occurred at intervals throughout this time period26,49. We do not observe any obvious indicators of drought in bison samples from the Late Holocene but changes in vegetation type may lower the amount of nitrogen available in soils and dampen the signal of physiological stress58. A wide range of δ13C values and more C4 plant material is recorded in Late Holocene bison (Table 2, Figs 3, 4), suggesting diverse vegetation utilized and a continued shift towards extended growing seasons39,41. Pollen records indicate that Poaceae increased in abundance during the Late Holocene and the first appearance of Salaginella densa (spikemoss) is documented in the Northern Great Plains50. The ground cover provided by spikemoss and its ability to persist in dry conditions provides protection from erosion and forage to subsist on during lean winter months. Its expansion likely increased foraging capacity and contributed to the immense presence of bison on the prairie during the Late Holocene.

Coinciding with the environmental changes that took place during the Late Holocene is the rise of a more complex human ecosystem throughout North America. How humans influenced landscapes, bison behavior, and available food supplies during the Holocene are currently not well understood but research suggests they had an active role in the Great Plains ecosystem59. Bison’s past response to changing composition of habitat remains unclear but their ability to adapt and exploit a variety of resources is attributed to the species’ long-term survival over other megafauna.

Finally, we compared isotopic values of modern bison dentin from TRNP with ancient bison from the Late Pleistocene through the Late Holocene. We observe comparatively low variability in modern bison stable isotopes (Table 2, Figs 3, 4). TRNP bison have a more restricted rangeland than their ancient counterparts as well as a presumably shorter window for sample collection. Modern bison are depleted in 13C, similar to Late Pleistocene bison (Figs 3, 4), indicating a diet of 100% C3 plant material (Table 2) despite different climatic conditions experienced by the temporal groups. Nitrogen values are notably lower than in other bison groups (Table 2, Fig. 4), indicating no evidence of nutritional stress and adequate available moisture27. While low variation may be attributed to small sample size, other studies have found similar results in several living herds25,39. Tieszen (1994)13 showed that the Wind Cave National Park bison herd in South Dakota had a diet with more C4 plants but bison also contained a small amount of δ13C variability within the herd. The Catalina Island bison population also exhibits a comparable δ13C average and low variability22. Modern Yellowstone National Park bison exhibit low variability in δ13C values and a similar mean to the TRNP bison in this study despite their ability to cover much larger areas and complete substantial elevational migrations37,60. Whether this trend in low variability in modern bison diet is due to restricted rangelands and herd management practices or if it is a result of a narrowing in plasticity from the recent genetic bottleneck in bison history is still not clear. We would expect that if it were only due to the habitat restrictions imposed upon modern bison, we would observe more variability in Yellowstone herds.

Understanding the predecessors of present-day bison may unlock new views for reintroducing them more broadly to the North American landscape. These techniques are already influencing management decisions for European bison (Bison bonasus). European bison had to overcome similar environmental challenges as North American species during the terminal Pleistocene and are also predominately constricted to limited rangelands today61. Most habitat of modern European bison is forested but their morphological adaptations suggest they evolved in open grasslands62 and then moved into woodland areas as the forests expanded and pressure from humans increased29. Isotopic studies of the ancient Eurasian steppe bison (Bison priscus) are informing conservation strategies for their ecological successor, Bison bonasus63. Several studies have found that Bison priscus did rely heavily on grazing, with more browse incorporated over time, as woody vegetation became more accessible52,61. This information makes the introduction of European bison to more open grassland habitats a plausible strategy for large scale restoration and is an example of the value of conservation paleobiology for current species management.

The North American landscape has been transformed dramatically during the last 250 years, and with few exceptions, bison are no longer allowed to migrate or range widely in localities where they currently exist. Further, the extreme population bottleneck experienced by bison at the end of the 19th century has left the species with only a microcosm of the genetic toolkit that it once wielded for adaptation. Thus, both the resiliency of the species and the landscape it once inhabited have been altered in a manner unprecedented since the last ice age. We may expect that genetically isolated and spatially confined herds will be the most challenged by environmental fluctuations64. Range expansion efforts such as opening of new state, federal, and tribal lands to bison and establishment of conservation herds on private lands are already underway, and bison range is currently expanding, but only at incrementally small amounts in comparison to the native range of the species.

Despite limitations imposed on present day herds, isotopic relationships identified here have provided a unique glimpse at paleoecology that is relevant to current management of the species. Managers would benefit from a spatially and temporally expanded study of bison isotopic profiles throughout the known historic range of the species. An evaluation of historic genetic diversity of the species may also reveal pre-extirpation global and local herd level values that can be used in parallel with isotopic data to illuminate ancient bison ecology and inform management. The common occurrence of bison remains in archaeological collections curated in facilities throughout North America makes this effort feasible and demonstrates the value of such collections to present day management of species and systems.

Materials and Methods

Sample assemblage

Ancient bison bone and tooth samples were collected from four North Dakota museum collections: North Dakota Heritage Center and State Museum (State Historical Society of North Dakota), Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site, University of North Dakota’s Department of Anthropology, and University of North Dakota’s Biology Museum. Samples included in this project were collected as part of twenty-one previously excavated archaeological sites in North Dakota and one previously excavated site in northern South Dakota (Fig. 1). The context of the archaeological sites encompasses a large temporal scale from the Late Pleistocene throughout the Holocene. Holocene sites are associated with each North Dakota Native American cultural tradition as defined by long standing archaeological schema including Plains Village (AD 1200–1800’s), Plains Woodland (400 BC to AD 1700’s), Plains Archaic (5,500 BC to 400 BC) and Paleo-Indian (11,500 to 5,500 BC). To avoid repeat sampling of bison individuals, we selected the right 3rd molar whenever possible. In other cases, we selected the molars or large premolars from the right side of the jawbone. Specimens were also chosen from different stratigraphic layers in the archaeological site context. While every effort was made to not repeat samples in the assemblage, there is a minute chance that repeats were made in some cases.

The integrity of skeletal elements was observed under stereo microscopy, revealing well preserved tissues at surfaces and on cross section of bones and teeth. Preservation quality was determined by a clear delineation between cortical and spongy material with little discoloration, compact tooth dentin and opalescent enamel (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Modern bison teeth were obtained from animals (n = 5) culled for management purposes or those dying of natural causes within the North and South Units of TRNP. Bison range at TRNP includes two geographically separate units encompassing in total 28,542 ha the badlands of Western North Dakota. The Little Missouri River traverses park lands from south to north, and the landscape is characterized by stratified clay buttes capped with clinker and interspersed with lignite and fossils dating to the Paleocene Epoch. Annual precipitation is 38.1 cm, and vegetative communities include mixed grass prairie and sage (Salvia and Artemisia spp.) and other woody shrubs in uplands, cottonwood (Populus deltoides) galleries along riparian corridors, ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) groves in draws, and juniper (Juniperus spp.) stands along north facing slopes. Temperature varies widely, with means ranging from highs of approximately +29 °C in summer to lows of −18 °C in winter, with extremes sometimes ranging +43 to −43 °C.

At TRNP, bison forage alongside feral horses (Equus caballus), longhorn cattle (Bos taurus), elk (Cervis elaphus), pronghorn antelope (Antilocapra americana), mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus), moose (Alces alces), sheep (Ovis canadensis), black-tailed prairie dogs (Cynomys ludovicianus), and other small mammals. Park lands are fenced, and in the absence of predators, bison are managed to prevent overgrazing through roundups, after which excess animals are transferred primarily to tribes. Herds have typically been allowed to range between 100–300 individuals in the North Unit and between 300–500 in the South Unit, in alignment with a forage allocation model and perceived social carrying capacity48,65,66.

Research was approved by the University of North Dakota (UND) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol number 1511-5) and the UND Institutional Biosafety Committee (registration number IBC-201511-007). All methods and experiments were performed within the guidelines and regulations for the use of experimental animal specimens.

All archaeological samples were selected from human derived contexts. This provides potential to access both bison ecology and human selection processes that resulted in the culling and ultimate deposition of individual skeletal elements in the archaeological record. We acknowledge the human induced bias in our sample. Taking this bias into account allows us to access a record of bison population dynamics otherwise unavailable as a result of the late 19th century population bottleneck.

Sample preparation and isotope analysis

Sections of cortical bone or tooth dentin weighing 1–3 grams were cut from bison specimens using a band saw. Tooth dentin samples were taken in 0.5 to 1 inch contiguous pieces from dentin underlying enamel in the orientation of crown to cusp. Some tooth dentin portions included root material. Samples were then sent to the University of California Irvine (UCI) Keck Carbon Cycle Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory where they were decalcified in 1 N HCl and then gelatinized at 60 °C, pH of 2, and ultrafiltered to select for a high molecular weight fraction (>30 kDa). Aliquots of ultrafiltered collagen were measured on a Fisons NA1500NC elemental analyzer/Finnigan Delta Plus isotope ratio mass spectrometer to obtain δ13C and δ15N values at a precision of <0.1‰ and <0.2‰, respectively. Stable isotope measurements were determined on amino acid hydrolysate samples. Samples with C:N atomic ratios between 2.9 and 3.6 are indicative of well-preserved collagen46,67 and were then measured for 14C dating at the UCI Keck AMS facility using the methods outlined in Lohse et al.11. The error range for 14C ages (BP) in this study is ±15–35 years. All 13C to 12C ratios were reported relative to the Vienna PeeDee Belemnite (VPDB) standard and all 15N to 14N ratios are reported relative to the Ambient Inhalable Reservoir (AIR) standard.

14C Calibration and temporal episodes

14C ages were calibrated using OxCal 4.368 and the IntCal13 curve69 for the Northern Hemisphere. All bison sample ages are reported in calibrated years before present (cal BP) and are within a 95% confidence interval. The median of the confidence interval was used as the sample date for separation into temporal episodes. All δ13C values dated before 1800 AD were adjusted by -1.5‰ to account for the reduction in atmospheric CO2 due to the increased burning of fossil fuels after the Industrial Revolution13.

The temporal range was split into episodes to allow comparisons between bison from the Late Pleistocene to modern. The episodes follow formal Holocene subdivisions recognized by the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) and is based on data from Greenland ice cores, pollen records, lake sediments, and Global Stratotype Section and Points (GSSPs)47. The Pleistocene-Holocene boundary was marked at 11.7 thousand years ago. The Holocene was split into four episodes, Early Holocene (11.7 to 8.2 thousand years ago), Middle Holocene (8.2 to 4.2 thousand years ago), and Late Holocene (4.2 to 100 years ago)47. Modern bison are also considered an episode.

δ13C and δ15N data analysis

We used generalized additive models (GAMs) to illustrate bison carbon and nitrogen isotopes over time with R statistical software and the package “mgcv”70. This method allows the estimation of isotope values between data points, providing a continuous view of bison isotopic fluctuations throughout the Holocene with a 95% confidence interval. GAMs were modeled with a gaussian distribution, an identity link function, and a smoothing parameter on time (k = 5).

The δ13C means of temporal episodes were also used to calculate the percentage of C3 and C4 grasses in bison using equation 1, modified from Carlson et al. (2018)32.

| 1 |

where δ13Ccollagen includes a 6.3‰ adjustment for trophic level fractionation specific to bison16,66, δ13C C4 = −12.5‰ and δ13CC3 = −26.5‰.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Park Service agreement (P16AC00001) to I.V.O. and B.M. The authors wish to thank Robert Bryson (NPS Midwest Regional Office) and Ann Bauermeister (NPS Midwest Archaeological Center) for their support for this project. We are grateful for the bison specimens used in this study which were provided by the North Dakota Heritage Center and State Museum (Bismarck), the State Historical Society of North Dakota (Bismarck), Knife River Indian Villages National Historic Site (Stanton), UND Museum and Department of Anthropology, and the UND Biology Museum. We thank Dennis Toom, Melinda Leach, and Robert Seabloom for providing part of historic bison samples, Robert Newman for statistical guidance, Phoebe Stubblefield for help with preparing bone and tooth samples. We are grateful to Jenna Folluo and Taylor Holm for help with creating the GIS archaeological site map. We also express gratitude to Anders Angerbjörn and Kenneth Cannon for reading the manuscript and providing critical comments and the anonymous reviewers whose insight and feedback greatly improved the quality of this paper. We acknowledge the Keck Carbon Cycle Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at the University of California Irvine and John Southon for isotope analysis of bison specimens.

Author contributions

B.M. and I.V.O. performed the study design and methodology. B.M., J.S., F.S. and I.V.O. contributed to sample collection. G.D. conducted preparing samples for isotope analyses and statistical evaluation of the isotope results. J.S., B.M., I.V.O. and G.D. provided funding acquisition. G.D., B.M. and I.V.O. contributed to the writing of original draft. G.D. prepared the tables and illustrations. All authors provided critical interpretations of the results and evaluations of the drafts.

Data availability

All data generated for this study are included within this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-019-52873-4.

References

- 1.Meltzer DJ. Pleistocene overkill and North American mammalian extinctions. Annu. Rev. Anthropol. 2015;44:33–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-anthro-102214-013854. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mann DH, et al. Life and extinction of megafauna in the ice-age Arctic. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:14301–14306. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516573112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lorenzen ED, et al. Species-specific responses of Late Quaternary megafauna to climate and humans. Nature. 2011;479:359–364. doi: 10.1038/nature10574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooper A, et al. Paleoecology. Abrupt warming events drove Late Pleistocene Holarctic megafaunal turnover. Science. 2015;349:602–606. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Froese D, et al. Fossil and genomic evidence constrains the timing of bison arrival in North America. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:3457–3462. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620754114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heintzman PD, et al. Bison phylogeography constrains dispersal and viability of the Ice Free Corridor in western Canada. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:8057–8063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601077113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilmour DM, et al. Chronology and ecology of late Pleistocene megafauna in the northern Willamette Valley, Oregon. Quat. Res. (United States) 2015;83:127–136. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro B, et al. Rise and fall of the Beringian steppe bison. Science. 2004;306:1561–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.1101074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lott, D. F. American bison: A natural history in Organisms and environments, 229 p. (Univ. of California Press, 2002).

- 10.Hedrick PW. Conservation genetics and North American Bison (Bison bison) J. Hered. 2009;100:411–420. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esp024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lohse JC, Madsen DB, Culleton BJ, Kennett DJ. Isotope paleoecology of episodic mid-to-late Holocene bison population expansions in the Southern Plains, USA. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2014;102:14–26. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoppe KA, Paytan A, Chamberlain P. Reconstructing grassland vegetation and paleotemperatures using carbon isotope ratios of bison tooth enamel. Geology. 2006;34:649–652. doi: 10.1130/G22745.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tieszen, L. L. Stable isotope analyses and diet determination. In Skeletal Biology in the Great Plains 261–282 (Smithsonian Press, 1994).

- 14.Schwarcz, H. P., White, C. D. & Longstaffe, F. J. Stable and radiogenic isotopes in biological archaeology: Some applications. In Isoscapes: Understanding movement, pattern, and process on Earth through isotope mapping 335–356 (Springer, 2010).

- 15.Tykot, R. H. Stable isotopes and diet: You are what you eat. Phys. Methods Archaeom (2004).

- 16.Manolagas SC. Birth and death of bone cells: Basic regulatory mechanisms and implications for the pathogenesis and treatment of osteoporosis. Endocrine Reviews. 2000;21:115–137. doi: 10.1210/edrv.21.2.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ambrose S, DeNiro M. The Isotopic ecology fo East African Mammals. Oecologia. 1986;69:395–406. doi: 10.1007/BF00377062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dalerum F, Angerbjörn A. Resolving temporal variation in vertebrate diets using naturally occurring stable isotopes. Oecologia. 2005;144:647–658. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0118-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Metcalfe, J. Z. Late Pleistocene climate and proboscidean paleoecology in North America: insights from stable isotope compositions of skeletal remains (University of Western Ontario, 2011).

- 20.Balasse M, Bocherens H, Mariotti A, Ambrose SH. Detection of dietary changes by intra-tooth carbon and nitrogen isotopic analysis: An experimental study of dentine collagen of cattle (Bos taurus) J. Archaeol. Sci. 2001;28:235–245. doi: 10.1006/jasc.1999.0535. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Clementz MT. New insight from old bones: stable isotope analysis of fossil mammals. J. Mammal. 2012;93:368–380. doi: 10.1644/11-MAMM-S-179.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cotton JM, Cerling TE, Hoppe KA, Mosier TM, Still CJ. Climate, CO2, and the history of North American grasses since the Last Glacial Maximum. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1501346. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van der Merwe NJ, Medina E. The canopy effect, carbon isotope ratios and foodwebs in Amazonia. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1991;18:249–259. doi: 10.1016/0305-4403(91)90064-V. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coppedge BR, Leslie DM, Shaw JH. Botanical composition of bison diets on tallgrass prairie in Oklahoma. J. Range Manag. 1998;51:379–382. doi: 10.2307/4003321. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feranec RS. Stable carbon isotope values reveal evidence of resource partitioning among ungulates from modern C3-dominated ecosystems in North America. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2007;252:575–585. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Valero-Garcés BL, et al. Holocene climate in the Northern Great Plains inferred from sediment stratigraphy, stable isotopes, carbonate geochemistry, diatoms, and pollen at Moon Lake, North Dakota. Quat. Res. 1997;48:359–369. doi: 10.1006/qres.1997.1930. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hobson KA, Alisauskas RT, Clark RG. Stable-nitrogen isotope enrichment in avian tissues due to fasting and nutritional stress: Implications for isotopic analyses of diet. Condor. 1993;95:388–394. doi: 10.2307/1369361. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fizet M, et al. Effect of diet, physiology and climate on carbon and nitrogen stable isotopes of collagen in a late Pleistocene anthropic palaeoecosystem: Marillac, Charente, France. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1995;22:67–79. doi: 10.1016/S0305-4403(95)80163-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofman-Kamińska E, Bocherens H, Borowik T, Drucker DG, Kowalczyk R. Stable isotope signatures of large herbivore foraging habitats across Europe. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0190723. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0190723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bocherens H, Pacaud G, Lazarev PA, Mariotti A. Stable isotope abundances (13C,15N) in collagen and soft tissues from Pleistocene mammals from Yakutia: Implications for the palaeobiology of the mammoth steppe. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 1996;126:31–44. doi: 10.1016/S0031-0182(96)00068-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fox-Dobbs K, Leonard JA, Koch PL. Pleistocene megafauna from eastern Beringia: Paleoecological and paleoenvironmental interpretations of stable carbon and nitrogen isotope and radiocarbon records. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2008;261:30–46. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Carlson K, Bement LC, Carter BJ, Culleton BJ, Kennett DJ. A Younger Dryas signature in bison bone stable isotopes from the southern Plains of North America. J. Archaeol. Sci.: Reports. 2018;21:1259–1265. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coltrain JB, et al. Rancho la Brea stable isotope biogeochemistry and its implications for the palaeoecology of late Pleistocene, coastal southern California. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2004;205:199–219. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2003.12.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feranec RS, Hadly EA, Paytan A. Stable isotopes reveal seasonal competition for resources between late Pleistocene bison (Bison) and horse (Equus) from Rancho La Brea, southern California. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2009;271:153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.palaeo.2008.10.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feranec RS, MacFadden BJ. Evolution of the grazing niche in Pleistocene mammals from Florida: Evidence from stable isotopes. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2000;162:155–169. doi: 10.1016/S0031-0182(00)00110-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zazula GD, MacKay G, Andrews TD. A late Pleistocene steppe bison (Bison priscus) partial carcass from Tsiigehtchic, Northwest Territories, Canada. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2009;28:2734–2742. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.06.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berini JL, Badgley C. Diet segregation in American bison (Bison bison) of Yellowstone National Park (Wyoming, USA) BMC Ecol. 2017;17:27. doi: 10.1186/s12898-017-0137-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leyden JJ, Oetelaar GA. Carbon and nitrogen isotopes in archeological bison remains as indicators of paleoenvironmental change in southern Alberta. In Great Plains. Research. 2001;11:3–23. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Widga C, Walker JD, Stockli LD. Middle Holocene bison diet and mobility in the eastern Great Plains (USA) based on δ13C, δ18O, and87Sr/86Sr analyses of tooth enamel carbonate. Quat. Res. 2010;73:449–463. doi: 10.1016/j.yqres.2009.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jahren AH, Todd LC, Amundson RG. Stable isotope dietary analysis of bison bone samples from the Hudson-Meng bonebed: effects of paleotopography. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1998;25:465–475. doi: 10.1006/jasc.1997.0248. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cannon KP. The analysis of a Late Holocene bison skull from Fawn Creek, Lemhi County, Idaho, and its implications for understanding the history and ecology of bison in the intermountain west. US Natl. Park Serv. Publ. Pap. 1997;59:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayewski P, et al. Holocene climate variability. Quat. Res. 2004;62:243–255. doi: 10.1016/j.yqres.2004.07.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marsicek J, Shuman BN, Bartlein PJ, Shafer SL, Brewer S. Reconciling divergent trends and millennial variations in Holocene temperatures. Nature. 2018;554:92–96. doi: 10.1038/nature25464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alley RB, et al. Holocene climatic instability: A prominent, widespread event 8200 yr ago. Geology. 1997;25:483–486. doi: 10.1130/0091-7613(1997)025<0483:HCIAPW>2.3.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deniro MJ. Postmortem preservation and alteration of in vivo bone collagen isotope ratios in relation to palaeodietary reconstruction. Nature. 1985;317:806–809. doi: 10.1038/317806a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Van Klinken GJ. Bone collagen quality indicators for palaeodietary and radiocarbon measurements. J. Archaeol. Sci. 1999;26:687–695. doi: 10.1006/jasc.1998.0385. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Walker MJC, et al. Formal subdivision of the Holocene Series/Epoch: A Discussion Paper by a Working Group of INTIMATE (Integration of ice-core, marine and terrestrial records) and the Subcommission on Quaternary Stratigraphy (International Commission on Stratigraphy) J. Quat. Sci. 2012;27:649–659. doi: 10.1002/jqs.2565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Westfall JA, Irby LR. A forage allocation model for the four ungulate species in Theodore Roosevelt National Park. J. Environ. Manage. 1993;64:153–169. doi: 10.1006/jema.2001.0514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yansa CH. The timing and nature of Late Quaternary vegetation changes in the northern Great Plains, USA and Canada: A re-assessment of the spruce phase. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2006;25:263–281. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.02.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grimm EC, Donovan JJ, Brown KJ. A high-resolution record of climate variability and landscape response from Kettle Lake, northern Great Plains, North America. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2011;30:2626–2650. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2011.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mandel RD, Murphy LR, Mitchell MD. Geoarchaeology and paleoenvironmental context of the Beacon Island site, an agate basin (Paleoindian) bison kill in northwestern North Dakota, USA. Quat. Int. 2014;342:91–113. doi: 10.1016/j.quaint.2014.06.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rivals F, Solounias N, Mihlbachler MC. Evidence for geographic variation in the diets of late Pleistocene and early Holocene Bison in North America, and differences from the diets of recent Bison. Quat. Res. 2007;68:338–346. doi: 10.1016/j.yqres.2007.07.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pielou, E. After the ice age: The return of life to glaciated North America. (University Of Chicago Press,1991).

- 54.Jacobson, G. L., Webb, T. & Grimm, E. C. Patterns and rates of vegetation change during the deglaciation of eastern North America. In North America and Adjacent Oceans During the Last Deglaciation (Geological Society of America, 2015).

- 55.Shuman BN, Marsicek J. The structure of Holocene climate change in mid-latitude North America. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016;141:38–51. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2016.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cannon KP, Hughes SH, Simpson C. The ecology of Early-Holocene bison in the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem, Wyoming: preliminary results from the Horner Site. Curr. Res. Pleistocene. 2010;27:161–163. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Commerford JL, et al. Regional variation in Holocene climate quantified from pollen in the Great Plains of North America. Int. J. Climatol. 2018;38:1794–1807. doi: 10.1002/joc.5296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Craine JM, et al. Isotopic evidence for oligotrophication of terrestrial ecosystems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2018;2:1735–1744. doi: 10.1038/s41559-018-0694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Roos CI, Zedeño MN, Hollenback KL, Erlick MMH. Indigenous impacts on north american great plains fire regimes of the past millennium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2018;115:8143–8148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1805259115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kauffman, M. J. et al. Wild Migrations: Atlas of Wyoming’s Ungulates. 26–27 (Oregon State University Press, 2018).

- 61.Bocherens H, Hofman-Kamińska E, Drucker DG, Schmölcke U, Kowalczyk R. European bison as a refugee species? Evidence from isotopic data on Early Holocene bison and other large herbivores in northern Europe. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0115090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0115090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kerley GIH, Kowalczyk R, Cromsigt JPGM. Conservation implications of the refugee species concept and the European bison: King of the forest or refugee in a marginal habitat? Ecography. 2012;35:519–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0587.2011.07146.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stuart, A. J. Late Pleistocene Megafaunal Extinctions. In Extinctions Near Time. 257–269 (Springer, 1999).

- 64.USGRCP. Impacts, Risks, and Adaptation in the United States: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume II: Report-in-Brief. (U.S. Global Change Research Program, 2018).

- 65.Harmon, D. At the open margin: the NPS’s administration of Theodore Roosevelt National Park. (Theodore Roosevelt Nature and History Association, 1986).

- 66.Norland JE, Irby LR, Marlow CB. Determination of optimum stocking rate in Theodore Roosevelt National Park. J. Environ. Manage. 1985;21:225–239. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ambrose, S. & Norr, L. Experimental evidence for the relationship of the carbon isotope ratios of whole diet and dietary protein to those of bone collagen and carbonate. In Prehistoric human bone 1–38 (1993).

- 68.Bronk Ramsey C. Bayesian Analysis of Radiocarbon Dates. Radiocarbon. 2009;51:337–360. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200033865. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reimer PJ, et al. IntCal13 and Marine13 Radiocarbon Age Calibration Curves 0–50,000 Years cal BP. Radiocarbon. 2013;55:1869–1887. doi: 10.2458/azu_js_rc.55.16947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wood SN. Fast stale restricted maximum likelihood and marginal likelihood estimation of semiparametric generalized linear models. J. R. Stat. Soc. 2011;73:3–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9868.2010.00749.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated for this study are included within this paper.