Abstract

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have been shown to hinder cardiomyocyte signaling, raising concerns about their safety during pregnancy. Approaches to assess SSRI-induced effects on fetal cardiovascular cells following passage of drugs through the placental barrier in vitro have only recently become available. Herein, we report that the SSRIs, fluoxetine and sertraline, lead to slowed cardiomyocyte calcium oscillations and induce increased secretion of troponin T and creatine kinase-MB with reduced secretion of NT-proBNP, three key cardiac injury biomarkers. We show the cardiomyocyte calcium handling effects are further amplified following indirect exposure through a placental barrier model. These studies are the first to investigate the effects of placental barrier co-culture with cardiomyocytes in vitro and to show cardiotoxicity of SSRIs following passage through the placental barrier.

Keywords: placenta, placental barrier, tissue engineering, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, cardiomyocytes

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction

Historically, there has been a lack of a priori knowledge about whether medications would hinder fetal development, such as the thalidomide birth defects in the 1960s[1]. This is concerning as more than 90% of pregnant women report taking at least one medication during pregnancy[2,3]. Further complicating this are medications prescribed for co-presenting conditions, such as depression which is estimated at occurring in 20% of pregnant women[4]. The primary treatment for depression is selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which act by blocking serotonin reuptake thus creating more free serotonin within the synaptic cleft [4]. Fetal exposure rates to SSRIs are 6–8%, and continue to rise[5,6]. Moreover, there is widespread acceptance that SSRIs readily cross the maternal-fetal interface[7,8], termed the blood-placenta barrier (BPB), a barrier intended to limit fetal exposure to toxins prenatally. Given these trends, additional studies are needed to understand the effects resulting from medication use during pregnancy.

SSRIs have been linked to congenital heart disease (CHD), though inconsistently, with arguments claiming SSRIs cause no deleterious effects and others showing dramatic consequences and increased fetal development risks[4,9–12]. The two most common SSRIs are sertraline and fluoxetine, each being prescribed in 2% of pregnancies[2,13]. Previous literature has summarized the effects of both of these drugs on changes in cardiovascular physiology[14–16]. Both sertraline and fluoxetine have been linked to inhibition of ion channels (Na+, Ca2+, and K+), inhibition of L-type Ca2+ current in cardiomyocytes, and depressant effects on cardiovascular cells, where observed effects are drug-dependent[14,15,17]. In vivo, SSRIs have led to QT prolongation and syncope [4,18], sertraline has led to small left heart syndrome[10], and fluoxetine has been linked to bradycardia[16], suggesting SSRIs can lead to abnormal heart rhythms. Since QT interval, action potential duration, and calcium transients (CaT) all correlate[19,20], though not directly comparable, it is perhaps intuitive that these in vitro and in vivo results agree. Interestingly, while many of these studies suggest issues in cardiomyocyte cell-cell signaling, to our knowledge, few studies have evaluated drug-induced changes in cardiac injury biomarkers [21]. Specifically, creatine kinase-MB (CKMB) and troponin T have been suggested as cardiovascular defect biomarkers for newborns and children, given their usage as biomarkers for adults[21–23]. Similarly, N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) has been suggested as a cardiac load and heart failure biomarker, and may show changed expression levels when other cardiac biomarkers do not [21,24]. Another important development marker is vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM), which was previously shown to be impacted by SSRIs[25–27]. Thus, relating these biomarker expression levels to cardiovascular signaling changes may provide predictive measures to improve clinical care of women taking SSRIs during pregnancy.

The gold standard approach for fetal toxicity and developmental changes is the use of animal models. Although developmental cardiovascular disease models exist, they are primarily for evaluation of genetic mutation lethality[28,29], and do not adequately reflect direct drug-induced changes at the tissue or cellular levels during pregnancy. Moreover, animal models do not recapitulate the key features of the human placenta, raising questions as to their relevance to human physiology[30]. Thus, a critical need for improving the safety and efficacy of SSRIs during pregnancy, to ultimately maximize maternal benefit and minimize fetal harm, is the development and utilization of biomimetic in vitro models of the human placenta and developing fetus.

We have previously reported using a biomimetic placenta-fetus model system to study maternal-fetal transmission and fetal neural toxicity of Zika Virus, where our findings agreed with in vivo studies[31,32]. The model system mimics the complexity of the human BPB and allows for investigating the effects of drugs on the placenta and downstream fetal tissue. Herein, we utilized this model to determine: (1) whether the SSRIs fluoxetine and sertraline lead to changes in cardiomyocyte calcium transients, through direct exposure and indirect exposure following passage through the BPB; and (2) whether levels of CKMB, troponin T, NT-proBNP, and VCAM change in response to drug exposure. Given that fluoxetine and sertraline have elicited drug-specific effects despite being in the same class of drugs, we assessed whether the two drugs lead to the same effects in cardiomyocytes. We hypothesized that both drugs would lead to similar elongations in calcium transients, and that all biomarkers would show similar trends of higher secretions with increasing drug dosage. Herein, we report on SSRI-induced extended oscillation period for cardiomyocyte calcium transients, increases in CKMB, troponin T, and VCAM secretions, and BPB model-induced cardiomyocyte response changes. Collectively, these results improve: (1) our understanding of SSRIs’ impact on cardiomyocytes and, (2) the BPB’s influence in altering the drug-induced response of cardiomyocytes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell culture

BeWo cells (trophoblast) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and grown in F12-K medium (ATCC) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Gaithersburg, MD) and antibiotic-antimycotic (A/A, Gibco). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs, or endothelial cells) were purchased from Lonza and grown in Endothelial Cell Growth Medium (Promocell, Heidelberg, Germany). Induced pluripotent stem cell derived-cardiomyocytes (iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes; iCell Cardiomyocytes2, previously characterized[33–36]) were purchased from Fujifilm Cellular Dynamics (Madison, WI) and grown in plating and maintenance media, as per manufacturer’s protocols. For co-culture studies involving trophoblast and endothelial cells, HUVEC media was utilized, as in previous studies[31]. For indirect co-culture studies involving BPB models, fabricated as described below, and iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes, media appropriate for each cell type was used within the apical and basolateral compartments of the co-culture setup.

2.2. BPB Model Fabrication

BPB models were fabricated using gelatin methacrylate (GelMA, 10% w/v), decellularized placental extracellular matrix (pECM, 10% v/v), trophoblast cells, and endothelial cells, using a similar approach as previously described[31,37].

Briefly, hydrogel precursor solution was made by combining GelMA in cell culture media with a photo-initiator (Omnirad 2959, IGM Resins, The Netherlands) and pECM. Trophoblast were encapsulated within this solution, which was cast into acrylic molds and allowed to soft cure prior to UV crosslinking. These cell-laden hydrogels were placed in media, additional trophoblast seeded on top, and constructs cultured for 4 days, at which point endothelial cells were seeded on the reverse side of the gel. Models were grown for 7 days in total, prior to being incorporated into co-culture studies with cardiomyocytes.

Placental decellularization was also performed using previously established protocols[38]. In brief, frozen whole placental tissue purchased from Zen-Bio (Research Triangle Park, NC) was thawed and mechanically digested via surgical tools. Tissue was washed with antibiotic overnight and decellularized using sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 0.1%) at room temperature for 48 hours. The decellularized tissue was repeatedly washed over 2 days, frozen, and lyophilized. Following lyophilization, the tissue was digested via pepsin (10% w/w in 0.5M acetic acid) at 4°C for 48 hours. This solution was pH-adjusted to 7.4, the tissue pelleted, and supernatant run though cell strainer (40μm) and sterile filter (0.2μm). This sterile solution was the pECM added into BPB models.

2.3. BPB Model-Cardiomyocyte Exposure Assays

Cardiomyocytes were exposed to fluoxetine and sertraline through one of two methods: (1) directly, where drug was included in maintenance media given to cardiomyocytes at the start of drug exposure; or, (2) indirectly, where drug was added to the apical compartment of a co-culture setup (see Fig. 4) where the BPB model, in a transwell insert, separated the apical and basolateral compartments and cardiomyocytes were seeded in the basolateral compartment, indicating cardiomyocyte exposure to drug following its passage through the BPB. For all assays, glass bottom dishes (MatTek, Ashland, MA) were coated with fibronectin (Gibco) prior to seeding cardiomyocytes in plating media (Fujifilm Cellular Dynamics). After 4 hours, plating media was replaced with maintenance media, which was changed every 2 days thereafter. Cardiomyocytes were grown for 7 days prior to inclusion in indirect exposure co-culture studies involving the BPB model. For exposure studies, fluoxetine hydrochloride or sertraline hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich) was solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and added to either cardiomyocyte maintenance media or HUVEC media, for direct and indirect exposure studies, respectively, at the appropriate dosage (10, 100, or 1,000 ng/mL, final concentration, based on previously reported concentrations[7]). Media with DMSO but without drug was used as a no exposure control. Further, DMSO content was controlled across all groups, with all media having a concentration <1% DMSO. In all instances, the drug-containing media was given to cells on day 7 post-seeding. For indirect exposure studies, drug-containing media was used in the apical compartment while cardiomyocyte maintenance media was used in the basolateral compartment. Volumes and culture conditions were used as per manufacturer’s recommendations.

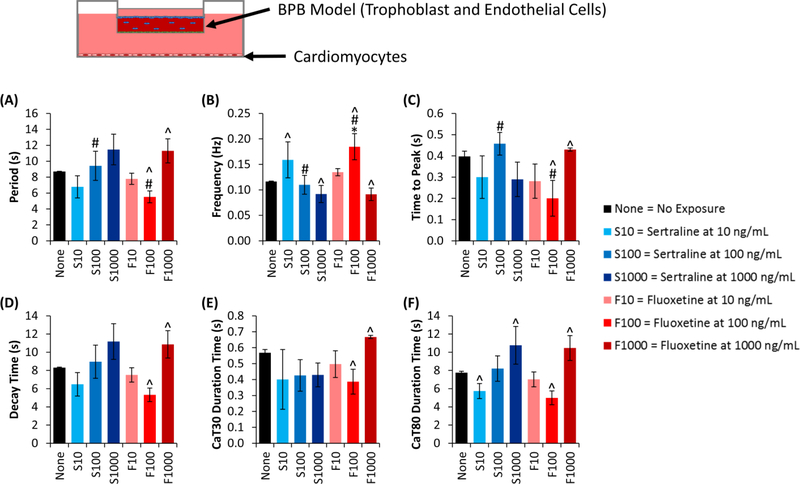

Fig. 4. Cardiomyocyte calcium handling response following SSRI exposure through BPB model.

Calcium intensity for cardiomyocytes in the basolateral compartment was quantified following exposure to SSRIs (either fluoxetine or sertraline) through a BPB model, using these metrics: (A) the peak-to-peak time (i.e. the period of the oscillations), (B) the frequency of oscillations, (C) the time to reach the peak, (D) the decay time, from peak to a minimum value, (E) the duration time at 30% calcium reuptake, and (F) the duration time at 80% calcium reuptake. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation, with n=3 for all groups. Where indicated by *, #, or ^, groups are significantly (p<0.05) different, where: *indicates a difference compared to the negative control, # indicates a difference compared to the other drug at the same dosage, and ^ indicates a difference compared to other dosages of the same drug.

2.4. Calcium Assays and Quantification

Following drug-exposure, Fluo-4 calcium dye (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was given to cells in maintenance media and incubated for 1 hour at 37°C. Dye was removed and replaced with maintenance media prior to live-cell imaging via confocal microscopy (Olympus FV3000) with incubation chamber. Resonant scanning was performed, imaging samples for 1500 frames at a rate of 15 frames per second (fps).

Quantification of calcium intensity data to evaluate spatial signaling was done using methods previously described in literature[39]. Cells were manually selected for analysis, which was performed on all cells individually and collectively within the field of view of the image.

A Fast Fourier transform (FFT) was performed on the raw intensity matrices for each calcium signaling video using MATLAB. Calcium-induced calcium release (CICR)[40] was excluded from the analysis. The built-in MATLAB FFT function (‘fft’) was used to generate a vector of amplitude values corresponding to discrete frequencies between 0 and the frame rate (15 Hz for these studies), with the same total number of values as the input video length and at an interval of frame rate divided by video length. To exclude imaginary amplitudes, we took the absolute value of the FFT matrix. FFT values for each discrete frequency were averaged across all samples for a given group. Further, we excluded the zero value as this likely did not contribute to oscillatory behavior (i.e. it was background fluorescence). The amplitudes output by the MATLAB function (‘fft’) had units of fluorescent intensity, where it was assumed that the fluorescent intensity at any given time is proportional to the number of cells fluorescing. Further, the amplitude output by the FFT corresponds to the relative contribution of that frequency to the overall signal[41]. Therefore, the FFT value can be interpreted as the proportion of cells fluorescing at that frequency. To generate this matrix, we divided the vector by the scalar sum of the amplitudes in the matrix. Since we were interested in general trends of calcium signaling frequency, we binned the FFT values into discrete bins of equivalent width. (Here, the bins have a width of 0.300 Hz, with the first frequency value being 0.018 Hz.) From there, we plotted the single-sided spectrum correlating to the first half of the bins.

For each sample, calcium intensity was further quantified using FIJI image analysis software[42]. From this intensity, calculations were manually performed in Excel to determine: average oscillation period, average oscillatory frequency, time to peak, decay time, and calcium transients at 30% and 80% reuptake (CaT30 and CaT80, respectively). All of these quantified metrics are explained visually in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Cardiomyocyte calcium handling response to SSRI exposure.

Calcium intensity for cardiomyocytes was quantified following direct exposure to SSRIs (either fluoxetine or sertraline) using multiple metrics: (A) the peak-to-peak time (i.e. the period of the oscillations), (B) the frequency of oscillations, (C) the time to reach the peak, (D) the decay time, from peak to a minimum value, (E) the duration time at 30% calcium reuptake, and (F) the duration time at 80% calcium reuptake. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation, with n=3 for all groups. Where indicated by *, #, or ^, groups are significantly (p<0.05) different, where: *indicates a difference compared to the negative control, # indicates a difference compared to the other drug at the same dosage, and ^ indicates a difference compared to other dosages of the same drug.

2.5. Co-culture DNA Content, XTT, and Viability Assays

Co-culture studies were performed to assess DNA content, metabolism, and viability of cardiomyocytes. Here, cardiomyocytes were seeded as above discussed previously, with either BeWo cells, HUVECs, or an acellular GelMA + pECM hydrogel seeded in a transwell insert for indirect co-culture with the cells. Cardiomyocytes and the other cells or hydrogel were in co-culture for 24 hours prior to assaying. DNA content of cardiomyocytes was quantified using a PicoGreen assay (Invitrogen). Metabolism was assessed using an XTT assay (Roche). Viability was assessed using a live-dead assay kit (Invitrogen) with samples imaged via fluorescent microscope (Nikon). All assays were performed as per manufacturer’s protocols.

2.6. Cardiomyocyte Secretions and ELISAs

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were used to determine secretions of biomarkers. Assay kits for Creatine Kinase MB and Troponin T were purchased from Ray Biotech (Norcross, GA). DuoSet assay kits for N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM) from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). All kits were used as per manufacturer’s protocols. At each time point, cell culture supernatant was collected, spun at 10,000g for 10 min at 4°C, then frozen at −80°C. Samples were thawed at room temperature prior to running each assay. Absorbance was measured via plate reader.

2.7. Statistical Methods and Analysis

For all assays, samples were run in biological triplicate (n=3), with independent cell samples within each group. Calcium handling samples were also run in technical replicate, with repeated observations of the same cell sample. Quantitative results are reported as a mean ± standard deviation (calculated using Excel), excluding FFT data, which are presented as binned values. Significance was determined using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s modification via Minitab or MATLAB, where p<0.05 was considered significant. For FFT data, statistical analysis was performed for all direct or indirect exposure groups at each frequency with symbols and comparisons noted in the appropriate figure caption. For all assays, excluding FFT, samples not sharing a letter within the same graph are significantly different and graphs with no letters shown indicate no statistically significant differences across all groups.

3. Results

3.1. Quantification of Calcium Signaling Intensity

Drug-induced effects on calcium transients were evaluated qualitatively by assessing changes in shape of the fluorescent intensity waveform (FIW, Fig. 1). The FIW was initially assumed to be spatially heterogeneous within a single sample (i.e. a single population of cells). However, it was observed that this was not the case; the cells’ fluorescent intensity changes were in sync, allowing a simplified analysis on the entire population of cells, rather than on each individual cell (Fig. 1A/B). The cells’ fluorescent intensity changes in sync was further supported by the reduction in noise when comparing a single cell’s intensity (Fig. 1A) to that of the population (Fig. 1B). Additionally, to ensure appropriate analysis of signals, the well-documented CICR effect[40] observed (Fig. 1A/B) was excluded from later FIW analysis. Following this decision to evaluate populations of cells, we evaluated how cardiomyocytes’ calcium signaling changed in response to drug exposure. Cardiomyocytes were exposed to fluoxetine and sertraline either directly (Fig. 1C) or indirectly (Fig. 1D). Changes in the FIW following direct exposure (Fig. 1C) suggested drug-induced effects for calcium influx to the sarcoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 1C). When comparing direct and indirect exposure, the period of oscillations was increased for all indirect exposure groups, including the no exposure control group (‘None’, Fig. 1D), compared to direct exposure groups. This suggests that the BPB model impacted cardiomyocyte calcium signaling on its own, independent of any drug exposure. Further studies were conducted to better explain why this may be the case (see section 3.4 below).

Fig. 1. Quantification of cardiomyocyte calcium handling.

(A) Representative time-dependent intensity profile for a single cell, showing oscillatory behavior and CICR in early time period. Red dots indicate peak values. (B) Representative time-dependent intensity profile for all cells within a field of view, indicating noise is reduced when evaluating the whole population. Red dots indicate peak values. (C/D) Calcium intensity across the field of view for cardiomyocytes exposed to vehicle control (None), fluoxetine at 1,000 ng/mL (F1000), or sertraline at 1,000 ng/mL (S1000) for 24 hours. Representative graphs are shown for each group. Cardiomyocytes were either (C) directly exposed to treatment, or (D) indirectly exposed following passage of drug through the placental barrier model.

Following the decision to evaluate FIW from populations of cells, we utilized a Fast Fourier transform (FFT) to determine the range of frequencies for each treatment group (Fig. 2), anticipating two clear peaks corresponding to a primary and secondary frequency of cell oscillations. However, this was not the case. When evaluating the direct exposure groups (Fig. 2A–G), we observed no differences between the negative control (None, Fig. 2A) and drug treatments (Fig. 2B–G). Significant differences were observed between sertraline and fluoxetine at a dosage of 100 ng/mL for 3 frequencies (Fig. 2C and Fig. 2F), though these differences are modest. When evaluating the indirect exposure groups (Fig. 2H–N), the only significant difference compared to the negative control (None, Fig. 2H) was fluoxetine at 100 ng/mL (Fig. 2M). As with direct exposure, differences between sertraline and fluoxetine were also observed in the indirect exposure groups at a dosage of 100 ng/mL, though only at two frequencies (Fig. 2J and Fig. 2M). Differences across dosages of a single drug was only observed for fluoxetine, at 5 frequencies (Fig. 2L–N), though these differences are modest. In total, though differences were observed between some groups, the change in FIW was not clarified from this data, indicating additional analysis was needed.

Fig. 2. Fast Fourier transform (FFT) of cardiomyocyte calcium handling.

(A-G) FFTs for calcium handling following direct exposure of cardiomyocytes to either sertraline (S, panels B-D) or fluoxetine (F, panels E-G) at 10, 100, or 1000 ng/mL, or exposed to a vehicle control (None, panel A). (H-N) Similar treatments and concentrations as panels A-G, though in panels H-N cardiomyocytes were indirectly exposed to drug, following the drug’s passage through the placental barrier. Data are reported as binned values, as described in the methods. Where indicated by *, #, or ^, groups are significantly (p<0.05) different at that frequency, where: *indicates a difference compared to the negative control, # indicates a difference compared to the other drug at the same dosage, and ^ indicates a difference compared to other dosages of the same drug (comparisons are across either the direct or indirect exposure groups).

3.2. SSRI-Induced Calcium Signaling Changes in Cardiomyocytes

We further evaluated changes in calcium signaling when cardiomyocytes were exposed to SSRIs (Fig. 3), given its correlation with action potential duration and QT interval in the myocardium[19,20], to better characterize changes in FIW. In quantifying these results, we found that sertraline at dosages of 100 and 1000 ng/mL led to a slight increase in period (Fig. 3A), and a corresponding slight decrease in frequency (Fig. 3B), not observed in other groups, though these were not significant differences (Fig. 3A/B). To further characterize the changes in FIW, the time to peak (Fig. 3C) and decay time (Fig. 3D) were determined, where these phases correspond with release and reuptake of calcium, respectively, into the sarcoplasmic reticulum of cardiomyocytes. Differences between fluoxetine and sertraline were observed when evaluating time to peak, with fluoxetine-exposed groups exhibiting a lower time to peak than sertraline groups, though no group differed significantly from the negative control (Fig. 3C). In evaluating decay time, indicative of the reuptake of calcium, we found no significant differences between groups, though there appears to be a trend that increasing sertraline dosage leads to increased decay time (Fig. 3D). We also evaluated duration time for the calcium transient at 30% reuptake and 80% reuptake[20,43]. We observed a significant increase in the CaT30 duration time for sertraline (1000 ng/mL) compared to fluoxetine (Fig. 3E). We found no differences across groups when evaluating CaT80 duration time, though fluoxetine (10 ng/mL) seems to increase this time (Fig. 3F). Overall, these data suggest some differential effect from each drug, though further studies are needed to more thoroughly characterize these effects.

3.3. BPB Modifies SSRI-Induced Cardiomyocyte Calcium Signaling Changes

Beyond direct exposure calcium handling changes in cardiomyocytes, we also evaluated indirect drug exposure calcium handling trends (Fig. 4). As before, we evaluated the period (Fig. 4A) and frequency (Fig. 4B) of calcium oscillations, finding significant differences between sertraline and fluoxetine at 100 ng/mL (Fig. 4A/B), and between fluoxetine at 100 ng/mL and the control (Fig. 4B). Notably, the period for all groups increased, with a corresponding frequency decrease, (Figs. 4A/3A) when the BPB model was present (Figs. 4B/3B). When evaluating time to peak, there were differences between dosage of fluoxetine (100 and 1000 ng/mL), and between drugs (sertraline and fluoxetine, both at 100 ng/mL) (Fig. 4C). In evaluating decay time, we found differences between fluoxetine dosages (100 and 1000 ng/mL) (Fig. 4D). We saw similar differences when evaluating the CaT30 duration time (Fig. 4E). When evaluating the CaT80 duration time, we found differences between sertraline dosages (10 and 1000 ng/mL) and between fluoxetine dosages (100 and 1000 ng/mL) (Fig. 4F). Overall, these data suggest that the BPB model leads to an increase in the period of calcium oscillations for cardiomyocytes, that fluoxetine dosage differentially impacts these oscillations in a non-dose-dependent manner, and that these changes primarily occur in the reuptake phase of calcium.

3.4. Cardiomyocytes Are Affected by Co-culture Conditions

To examine the apparent BPB-model induced effects on cardiomyocytes, we evaluated co-culture between cardiomyocytes and each BPB model component (Fig. 5). We found no significant differences in cardiomyocyte DNA content across groups (Fig. 5A). Moreover, no significant differences in metabolic activity were found between groups when evaluated at 6 hours (Fig. 5B) or at 24 (Fig. 5C) hours after addition of reaction mixture. With live-dead microscopy studies, we observed highly confluent cardiomyocyte populations in co-culture with acellular hydrogels and HUVECs, but visibly reduced confluency with BeWo co-culture (Fig. 5D). Thus, it is possible that BeWo cells within the BPB model are negatively impacting cardiomyocyte population viability. Further studies would be prudent to more thoroughly characterize why cardiomyocyte confluence and viability are negatively impacted by BeWo cells compared to HUVECs and acellular hydrogels, while the metabolic activity and DNA content of the populations remain comparable between all three groups.

Fig. 5. Cardiomyocyte Response to Co-culture Conditions.

(A) DNA content for cardiomyocytes indirectly co-cultured with an acellular GelMA hydrogel (Blank), HUVECs, or BeWo cells, following 1 day of co-culture. (B/C) XTT assay for cardiomyocytes following indirect co-culture with an acellular GelMA hydrogel, HUVECs, or BeWo cells. Measurements were taken (B) 6 hours and (C) 24 hours after addition of XTT reagent mixture. (D) Viability staining for cardiomyocytes following coculture with an acellular GelMA hydrogel, HUVECs, or BeWo cells (scale bar = 200μm). Throughout samples in co-culture with BeWo cells, there were clear regions where cardiomyocytes had lifted off the culture surface, not present in the Blank or HUVEC groups. For all graphs, groups not sharing a letter are significantly (p<0.05) different. Graphs with no letters indicate no significant differences across all groups. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation, with n=3 for all groups.

3.5. Myocardial Injury Biomarkers Show Drug-Dependent Effect

We further characterized cardiomyocyte damage by assessing secretion levels of CKMB and Troponin T[21] (Fig. 6). We observed significant differences in CKMB secretions for direct exposure to fluoxetine at 100 ng/mL, compared to all other groups (Fig. 6A). CKMB secretions in the basolateral compartment following indirect exposure showed no significant differences, though we observed a trend of lower dosages leading to higher secretions (Fig. 6B). These trends carried over when evaluating troponin T secretions (Figs. 6C/D). Following direct exposure, almost all of the groups fell below the detection limit of the assay kit (0.35 ng/mL) suggesting no deleterious effects to the cardiomyocytes (Fig. 6C). These levels increased following indirect exposure, though with no significant differences between groups (Fig. 6D). These data suggest that fluoxetine (100 ng/mL) may cause myocardial damage, but may not induce highly toxic effects.

Fig. 6. Cardiomyocyte Injury Marker Secretions in Response to Drug Exposure.

(A/B) Creatine Kinase MB secretions for cardiomyocytes either (A) directly exposed to the drugs (fluoxetine, F, or sertraline, S) at one of two dosages (100 or 1000 ng/mL), with a non-exposed (NoE) negative control, or (B) indirectly exposed to the drugs, via additional to apical compartment of placental barrier and secretions in basolateral compartment assessed. (C/D) Troponin T secretions for cardiomyocytes either (C) directly exposed to the drug, or (D) indirectly exposed to the drug, with annotation as stated above. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation, with n=3 for all groups. Where indicated by *, #, or ^, groups are significantly (p<0.05) different, where: *indicates a difference compared to the negative control, # indicates a difference compared to the other drug at the same dosage, and ^ indicates a difference compared to other dosages of the same drug.

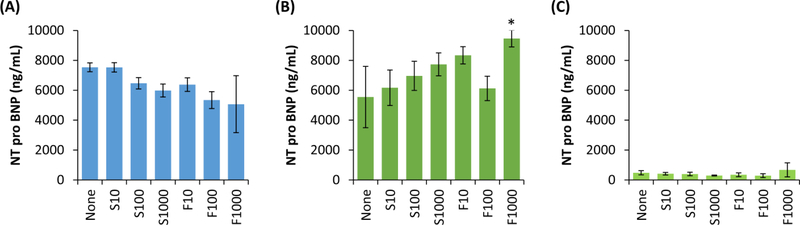

We also evaluated NT-proBNP as a cardiac biomarker given that its expression does not necessarily correlate with CKMB and Troponin T, providing a wider view of cardiac injury (Fig. 7). Counter to CKMB and Troponin T, we found that direct exposure to higher dosages of both sertraline and fluoxetine leads to decreases in NT-proBNP secretions from cardiomyocytes (Fig. 7A). Interestingly, when cardiomyocytes were indirectly exposed to drug, we observed a trend of increasing sertraline dosage led to increased NT-proBNP secretions in the basolateral compartment, though these were not significant differences (Fig. 7B). We observed fluoxetine at a dosage of 1000 ng/mL led to a significant increase in NT-proBNP secretions, whereas other dosages of fluoxetine did not (Fig. 7B). We found NT-proBNP secretions do not differ significantly across drug or dosage groups in the apical compartment (Fig. 7C). This suggests that NT-proBNP secretions, though impacted by the drugs, do not significantly cross from fetal into maternal compartment. Further, the BPB appears to influence whether increasing drug dosage leads to increased or decreased secretions.

Fig. 7. Cardiomyocyte secretions of NT-proBNP following exposure to SSRIs.

(A) Secretions of NT-proBNP from cardiomyocytes following 1 day of exposure to SSRIs (either sertraline, S, or fluoxetine, F) at one of three dosages (10, 100, or 1000 ng/mL), or no drug exposure (None). (B) Secretions in the basolateral compartment, where cardiomyocytes were indirectly exposed to the drug following passage through a BPB model. (C) Secretions in the apical compartment, indicating protein that was secreted in the basolateral compartment and passed through the BPB model. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation, with n=3 for all groups. Where indicated by *, #, or ^, groups are significantly (p<0.05) different, where: *indicates a difference compared to the negative control, # indicates a difference compared to the other drug at the same dosage, and ^ indicates a difference compared to other dosages of the same drug.

3.6. Myocyte Cell Adhesion Impacted by SSRIs

Previous work has shown that SSRIs modulate vascular cell CAM expression[25–27]. Given that VCAM is particularly important for cardiomyocyte function[44], we assessed whether iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes are similarly impacted by SSRIs. We found that cardiomyocytes directly exposed to sertraline show no difference in VCAM secretions, but that exposure to low dosages of fluoxetine (10 and 100 ng/mL) significantly increased VCAM secretions (Fig. 8A). When cardiomyocytes were indirectly exposed to drug, we only found significant differences between fluoxetine dosages (100 and 1000 ng/mL) (Fig. 8B). Notably, these secretions may be from cardiomyocytes in the basolateral compartment and/or HUVECs in the apical compartment. However, secretions in the apical compartment were lower than in the basolateral compartment (Fig. 8C). Overall, this suggests that sertraline has minimal impact on cardiomyocyte VCAM secretions while fluoxetine has an exposure-dependent effect. Fluoxetine may damage cardiomyocytes through direct exposure, but may provide some protective effect through indirect exposure. Additional studies are needed to clarify this exposure-dependent, counterintuitive effect.

Fig. 8. Secretions of VCAM following exposure to SSRIs.

(A) Secretions of VCAM from cardiomyocytes following 1 day of exposure to SSRIs (either sertraline, S, or fluoxetine, F) at one of three dosages (10, 100, or 1000 ng/mL), or no drug exposure (None). (B) Secretions in the basolateral compartment, where cardiomyocytes were indirectly exposed to the drug following passage through a BPB model. (C) Secretions in the apical compartment, indicating protein that was secreted in the basolateral compartment and passed through the BPB model or protein secreted by the cells within the BPB model in response to drug exposure. Data shown are mean ± standard deviation, with n=3 for all groups. Where indicated by *, #, or ^, groups are significantly (p<0.05) different, where: *indicates a difference compared to the negative control, # indicates a difference compared to the other drug at the same dosage, and ^ indicates a difference compared to other dosages of the same drug.

4. Discussion

The extent to which SSRIs impact fetal cardiac development has been inconsistent in the literature, with some studies arguing that SSRIs do not increase the risk of congenital heart defects, while others argue SSRIs can be extremely detrimental to development[10,45,46]. Therefore, the overall goal of this study was to better understand whether SSRIs influence cardiomyocytes, and the extent to which the BPB impacts the observed response. Given that sertraline and fluoxetine have been increasingly used during pregnancy over the past few decades, and sertraline in particular has been associated with fetal cardiac issues, we investigated whether there were drug-specific differences[2,10,14]. We hypothesized that both drugs would lead to reduced calcium transient frequencies and increased secretion of damage biomarkers, but that sertraline would be worse for cardiomyocytes than fluoxetine in all assays.

We evaluated changes in the calcium transient as a metric for changes to the action potential duration and QT interval, as these generally, though not directly, correlate[19,20]. Though these metrics have been previously studied in response to fluoxetine and sertraline[14,15,17], those studies utilized rat cardiomyocytes, and we are unaware of any studies utilizing human iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes to investigate these effects induced by SSRIs. We observed that the iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes exposed to SSRIs directly led to modest drug-specific differences in decay time and CatT30 duration time, though all other metrics showed no differences by drug. Cardiomyocytes that were indirectly exposed to SSRIs showed some differences between fluoxetine and sertraline at a dosage of 100 ng/mL (in period, frequency, and time to peak) and differences between fluoxetine dosages of 100 and 1,000 ng/mL (in in all metrics assessed). Taken together, this suggests that there may be minor differences leading to drug-specific mechanisms in altering cardiomyocyte calcium handling, but that the two drugs largely elicit a similar response. Other studies have evaluated how these drugs impact cardiomyocytes and have tried to elucidate the mechanism behind the observed effects. Park et al. found that fluoxetine prolonged the action potential duration at 50% and that both fluoxetine and sertraline inhibited L-type Ca2+ current[17], the latter of which is a mechanism for involved in cardiomyocyte contractility and electrical activity, and has been shown to be important in preventing cardiac arrhythmias[47,48]. This suggests that both drugs lead to elongation of the calcium transient, whereas we observed only a modest increase in elongation in response to drug treatment, whether or not the BPB model was utilized. In another study by Lee et al., it was observed that sertraline inhibited sodium, potassium, and calcium ion channel currents, at concentrations comparable to the study by Park et al., both of which were between 100 and 1000 ng/mL[14,17]. As before, this suggests sertraline at a high dosage (1000 ng/mL) should negatively impact the calcium transient, where we observed a modest, non-significant differences when utilizing this dosage. The data presented herein suggests modest changes to cardiomyocytes’ calcium handling, but further studies are necessary to explain a potential mechanism by which these SSRIs induce changes in calcium handling, for example evaluating drug interactions with the sodium-calcium exchanger (NCX), a prominent protein involved in cardiomyocyte calcium handling[49,50].

Beyond changes in calcium oscillations, we evaluated whether secretion of cardiac biomarkers was influenced by SSRI exposure as these changes could provide an easy-to-assess metric perinatally and potentially prenatally. We observed that direct exposure to fluoxetine at lower dosages (10 and 100 ng/mL) led to increased CKMB, troponin T, and VCAM, whereas sertraline induced no changes. For indirect exposure, a trend was observed of lower dosages of either drug leading to increased secretions of CKMB and troponin T, though these were not significant differences. There was no clear trend for VCAM secretions in response to indirect drug exposure. When evaluating NT-proBNP, we observed that direct exposure to SSRIs with increasing dosages led to modest decreases. Surprisingly, this trend was generally reversed for indirect exposure groups. These NT-proBNP studies are of particular interest as multiple studies have observed that NT-proBNP in maternal serum is higher when a pregnancy is complicated by disease, such as pre-eclampsia[51,52]. This suggests that NT-proBNP can be useful as a biomarker of cardiac stress during pregnancy, but that maternal and fetal measurements may be necessary to distinguish between maternal and fetal cardiac concerns as the placenta itself may influence the measured values. Taken all together, these biomarker secretion results suggest that: (1) fluoxetine and sertraline elicit differential effects when directly exposed to cardiomyocytes, with fluoxetine inducing increased injury biomarker secretion where sertraline does not, (2) the BPB may provide some protective effect against these drug-induced injury biomarker secretions, and (3) multiple cardiac proteins should be screened for to assess damage resulting from SSRI exposure. Others have also observed differences between the two drugs[53], though why this occurs remains unclear. One hypothesis is that the differences in chemical structure of these two molecules leads to differences in cardiomyocyte-drug interactions. However, extensive studies would be necessary to validate this hypothesis. Regarding the BPB model, the idea that it provides a protective effect is not new nor unreasonable. We observed a similar phenomenon previously when studying Zika virus using the model described herein[31], and intuitively, the placental barrier should limit fetal damage. This should be further studied to better understand the limitations to this protective effect and the mechanism by which it occurs. Regarding multiple biomarkers, the trends observed are beneficial, but whether they correlate to injury in vivo still needs to be determined. Nearly a decade ago, Kocylowski et al. sought to establish reference values for these markers, indicating cardiovascular injury, in postpartum cord blood[21]. They found that cardiac injury does indeed lead to abnormal levels of these biomarkers[21], supporting their use as biomarkers of congenital heart issues. Therefore, to build upon having previously validated biomarkers, the next key step to improving in vitro studies would be to correlate the in vitro and in vivo values of these biomarkers. This could improve the predictive value of in vitro placenta-fetus models to evaluate maternal and fetal cardiac injury.

One surprising aspect of the studies presented herein was the role the BPB model played in cardiomyocyte response to these drugs. We observed clear differences between direct and indirect exposure groups when evaluating calcium transients, where the indirect exposure, through the BPB model, led to periods nearly 3x the length as direct exposure groups. This suggests that the BPB model plays a more prominent role than we initially anticipated. To determine what factors within the model influenced cardiomyocyte behavior, we performed co-culture studies with each component of the BPB model, finding no changes in DNA content or metabolism of the cell population, though we observed markedly reduced confluency in cardiomyocyte layers when co-cultured with BeWo cells. This suggests that the trophoblast in the model are responsible for the observed changes in cardiomyocyte calcium handling response between direct and indirect exposure groups. Given that other studies have shown phenotypic effects from trophoblast are dependent upon the cell type[54], future studies should more thoroughly investigate the role of alternative trophoblast cell types, such as primary term-derived trophoblast, to improve placenta-fetus models.

Although this work provides additional information regarding fluoxetine and sertraline’s impact on cardiomyocytes and the role that the BPB plays, it is not without limitations. As mentioned above, one interesting facet was the extent to which the BPB caused changes in the cardiomyocyte response. Potentially, this was due to the specific cell types used (trophoblast cell line, primary endothelial cells, and iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes). It begs the question of whether alternative cell types, particularly primary trophoblast, would lead to similar observations, given that these cell types generally do not hinder fetal development and other studies have shown different responses between primary trophoblast and cell lines[54]. Additionally, calcium handling studies do not directly indicate changes in electrical signaling and myocardial contraction[20,55], thus future studies to investigate drug-induced changes to electrical signaling and muscle contraction are necessary. Future studies should also investigate the proteins involved and the mechanism behind the observed changes in calcium handling.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we assessed the extent to which iPSC-derived cardiomyocyte calcium transients and biomarker secretions are influenced by SSRIs by evaluating direct and indirect drug exposure. We observed a differential effect between drugs on calcium transients when cardiomyocytes were directly exposed to the drugs, but indirect exposure (passage through the BPB) seemed to moderate these effects. Further, we found that fluoxetine influenced CKMB, Troponin T, and VCAM secretions, whereas sertraline did not. This differential effects between drugs of the same class may be due to their chemical structure, though additional studies are needed to validate this hypothesis. To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies evaluating these parameters using iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes and evaluating the extent to which the placental barrier influences these effects. This will ultimately improve our ability to understand how SSRIs influence fetal development, and maybe enable improved clinical care through the knowledge gained.

Statement of Significance.

Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a class of antidepressants, during pregnancy continues to rise despite multiple studies showing potential for detrimental effects on the developing fetus. SSRIs are particularly thought to slow cardiovascular electrical activity, such as ion signaling, yet few, if any, methods exist to rigorously study these drug-induced effects on human pregnancy and the developing fetus. Within this study, we utilized a placenta-fetus model to evaluate these drug-induced effects on cardiomyocytes, looking the drugs’ effects on calcium handling and secretion of multiple cardiac injury biomarkers. Together, with existing literature, this study provides a platform for assessing pharmacologic effects of drugs on cells mimicking the fetus and the role the placenta plays in this process.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by a seed grant from the Sheikh Zayed Institute for Pediatric Surgical Innovation at Children’s National Medical Center and the A. James Clark School of Engineering at the University of Maryland. This work was also supported by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering/National Institutes of Health (NIBIB/NIH) Center for Engineering Complex Tissues (P41 EB023833). The authors acknowledge the BioWorkshop core facility in the Fischell Department of Bioengineering at the University of Maryland – College Park for use of the FV3000 Olympus Confocal microscope in imaging samples for calcium handling analysis. Additionally, we acknowledge Manelle Ramadan and Nikki Posnack, PhD, for their advice regarding analysis of calcium studies.

Footnotes

Disclosures

None of the authors have competing interests with the work presented herein.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Mcbride WG, Thalidiomide and congenital abnormalities, Lancet. 278 (1961) 1358. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(61)90927-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mitchell AA, Gilboa SM, Werler MM, Kelley KE, Louik C, Hernández-Díaz S, Medication use during pregnancy, with particular focus on prescription drugs: 1976–2008, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 205 (2011) 51.e1–51.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sinclair SM, Miller RK, Chambers C, Cooper EM, Medication Safety During Pregnancy: Improving Evidence-Based Practice, J. Midwifery Women’s Heal 61 (2016) 52–67. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Marchocki Z, Russell NE, Donoghue KO, Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and pregnancy: A review of maternal, fetal and neonatal risks and benefits, Obstet. Med 6 (2013) 155–158. doi: 10.1177/1753495X13495194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Shea AK, Oberlander TF, Rurak D, Fetal serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant exposure: Maternal and fetal factors, Can. J. Psychiatry 57 (2012) 523–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Andrade SE, Raebel MA, Brown J, Lane K, Livingston J, Boudreau D, Rolnick SJ, Roblin D, Smith DH, Willy ME, Staffa JA, Platt R, Use of antidepressant medications during pregnancy: a multisite study, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 198 (2008). doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.07.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Hendrick V, Stowe ZN, Altshuler LL, Hwang S, Lee E, Haynes D, Placental passage of antidepressant medications, Am. J. Psychiatry 160 (2003) 993–996. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.5.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Rampono J, Simmer K, Ilett KF, Hackett LP, Doherty DA, Elliot R, Kok CH, Coenen A, Forman T, Placental transfer of SSRI and SNRI antidepressants and effects on the neonate, Pharmacopsychiatry. 42 (2009) 95–100. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1103296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Alwan S, Friedman JM, Chambers C, Safety of Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors in Pregnancy: A Review of Current Evidence, CNS Drugs. 30 (2016) 499–515. doi: 10.1007/s40263-016-0338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Haskell SE, Hermann GM, Reinking BE, Volk KA, Peotta VA, Zhu V, Roghair RD, Sertraline exposure leads to small left heart syndrome in adult mice, Pediatr. Res 73 (2013) 286–293. doi: 10.1038/pr.2012.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Morrison JL, Riggs KW, Rurak DW, Fluoxetine during pregnancy: Impact on fetal development, Reprod. Fertil. Dev 17 (2005) 641–650. doi: 10.1071/RD05030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wichman CL, Moore KM, Lang TR, St Sauver JL, Heise RH, Watson WJ, Congenital heart disease associated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use during pregnancy., Mayo Clin. Proc 84 (2009) 23–7. doi: 10.4065/84.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Cooper WO, Willy ME, Pont SJ, Ray WA, Increasing use of antidepressants in pregnancy, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 196 (2007) 544.e1–544.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lee HA, Kim KS, Hyun SA, Park SG, Kim SJ, Wide spectrum of inhibitory effects of sertraline on cardiac ion channels, Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol 16 (2012) 327–332. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2012.16.5.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Pacher P, Ungvari Z, Kecskemeti V, Furst S, Review of Cardiovascular Effects of Fluoxetine, a Selective Serotonine Reuptake Inhibitor, Compared to Tricyclic Antidepressants, Curr. Med. Chem 5 (1998) 381–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Pacher P, Kecskemeti V, Cardiovascular Side Effects of New Antidepressants and Antipsychotics: New Drugs, old Concerns?, Curr. Pharm. Des 10 (2004) 2463–2475. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Park KS, Kong ID, Park KC, Lee JW, Fluoxetine Inhibits L-Type Ca2+and Transient Outward K+Currents in Rat Ventricular Myocytes, Yonsei Med. J 40 (1999) 144–151. doi: 10.3349/ymj.1999.40.2.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Yekehtaz H, Farokhnia M, Akhondzadeh S, Cardiovascular considerations in antidepressant therapy: an evidence-based review., J. Tehran Heart Cent 8 (2013) 169–76. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26005484 (accessed March 21, 2018). [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Vaughan Williams EM, QT and action potential duration., Heart. 47 (1982) 513–514. doi: 10.1136/hrt.47.6.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wang K, Terrar D, Gavaghan DJ, Mu-u-min R, Kohl P, Bollensdorff C, Living cardiac tissue slices: An organotypic pseudo two-dimensional model for cardiac biophysics research, Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol 115 (2014) 314–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2014.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kocylowski RD, Dubiel M, Gudmundsson S, Sieg I, Fritzer E, Alkasi Ö, Breborowicz GH, von Kaisenberg CS, Biochemical tissue-specific injury markers of the heart and brain in postpartum cord blood, Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 200 (2009) 273.e1–273.e25. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Neves AL, Cabral M, Leite-Moreira A, Monterroso J, Ramalho C, Guimarães H, Barros H, Guimarães JT, Henriques-Coelho T, Areias JC, Myocardial Injury Biomarkers in Newborns with Congenital Heart Disease, Pediatr. Neonatol 57 (2016) 488–495. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2015.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Neves AL, Cabral M, Leite-Moreira A, Monterroso J, Ramalho C, Guimarães H, Barros H, Guimarães JT, Henriques-Coelho T, Areias JC, Time-dependence of cardiac biomarker levels in newborns with congenital heart defects: Umbilical cord versus peripheral newborn blood, Int. J. Cardiol 214 (2016) 412–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.03.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Sugimoto M, Kuwata S, Kurishima C, Kim JH, Iwamoto Y, Senzaki H, Cardiac biomarkers in children with congenital heart disease, World J. Pediatr 11 (2015) 309–315. doi: 10.1007/s12519-015-0039-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kwee L, Baldwin HS, Shen HM, Stewart CL, Buck C, Buck CA, Labow MA, Defective development of the embryonic and extraembryonic circulatory systems in vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM-1) deficient mice., Development. 121 (1995) 489–503. doi: 10.1002/app.40137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dawood T, Barton DA, Lambert EA, Eikelis N, Lambert GW, Examining endothelial function and platelet reactivity in patients with depression before and after SSRI therapy, Front. Psychiatry 7 (2016). doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Lopez-Vilchez I, Diaz-Ricart M, Navarro V, Torramade S, Zamorano-Leon J, Lopez-Farre A, Galan AM, Gasto C, Escolar G, Endothelial damage in major depression patients is modulated by SSRI treatment, as demonstrated by circulating biomarkers and an in vitro cell model, Transl. Psychiatry 6 (2016) e886. doi: 10.1038/tp.2016.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Moon A, Mouse Models of Congenital Cardiovascular Disease, Curr. Top. Dev. Biol 84 (2008) 171–248. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(08)00604-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Conway SJ, Kruzynska-Frejtag A, Kneer PL, Machnicki M, Koushik SV, What cardiovascular defect does my prenatal mouse mutant have, and why?, Genesis. 35 (2003) 1–21. doi: 10.1002/gene.10152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Sastry BVR, Techniques to study human placental transport, Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev 38 (1999) 17–39. doi: 10.1016/S0169-409X(99)00004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Arumugasaamy N, Ettehadieh LE, Kuo CY, Paquin-Proulx D, Kitchen SM, Santoro M, Placone JK, Silveira PP, Aguiar RS, Nixon DF, Fisher JP, Kim PCW, Biomimetic Placenta-Fetus Model Demonstrating Maternal–Fetal Transmission and Fetal Neural Toxicity of Zika Virus, Ann. Biomed. Eng 46 (2018) 1963–1974. doi: 10.1007/s10439-018-2090-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Miner JJ, Cao B, Govero J, Smith AM, Fernandez E, Cabrera OH, Garber C, Noll M, Klein RS, Noguchi KK, Mysorekar IU, Diamond MS, Zika Virus Infection during Pregnancy in Mice Causes Placental Damage and Fetal Demise, Cell. 165 (2016) 1081–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Doherty KR, Talbert DR, Trusk PB, Moran DM, Shell SA, Bacus S, Structural and functional screening in human induced-pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes accurately identifies cardiotoxicity of multiple drug types, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 285 (2015) 51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Maddah M, Heidmann JD, Mandegar MA, Walker CD, Bolouki S, Conklin BR, Loewke KE, A non-invasive platform for functional characterization of stem-cell-derived cardiomyocytes with applications in cardiotoxicity testing, Stem Cell Reports. 4 (2015) 621–631. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2015.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Sirenko O, Cromwell EF, Crittenden C, Wignall JA, Wright FA, Rusyn I, Assessment of beating parameters in human induced pluripotent stem cells enables quantitative in vitro screening for cardiotoxicity, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 273 (2013) 500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2013.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Ivashchenko CY, Pipes GC, Lozinskaya IM, Lin Z, Xiaoping X, Needle S, Grygielko ET, Hu E, Toomey JR, Lepore JJ, Willette RN, Human-induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes exhibit temporal changes in phenotype, Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol 305 (2013) H913–H922. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00819.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Arumugasaamy N, Gudelsky A, Hurley‐Novatny A, Kim PCW, Fisher JP, Model Placental Barrier Phenotypic Response to Fluoxetine and Sertraline: A Comparative Study, Adv. Healthc. Mater (2019) 1900476. doi: 10.1002/adhm.201900476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Kuo CY, Guo T, Cabrera-Luque J, Arumugasaamy N, Bracaglia L, Garcia-Vivas A, Santoro M, Baker H, Fisher J, Kim P, Placental basement membrane proteins are required for effective cytotrophoblast invasion in a three-dimensional bioprinted placenta model, J. Biomed. Mater. Res. - Part A 106 (2018) 1476–1487. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.36350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Lembong J, Lerman MJ, Kingsbury TJ, Civin CI, Fisher JP, A Fluidic Culture Platform for Spatially Patterned Cell Growth, Differentiation, and Cocultures, Tissue Eng. Part A 24 (2018) 1715–1732. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2018.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Fabiato A, Calcium-induced release of calcium from the cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum, Am. J. Physiol. - Cell Physiol 14 (1983) C1–C14. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.245.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Heideman MT, Johnson DH, Burrus CS, Gauss and the History of the Fast Fourier Transform, IEEE ASSP Mag. 1 (1984) 14–21. doi: 10.1109/MASSP.1984.1162257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A, Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis, Nat. Methods 9 (2012) 676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Zhu R, Millrod MA, Zambidis ET, Tung L, Variability of Action Potentials Within and among Cardiac Cell Clusters Derived from Human Embryonic Stem Cells, Sci. Rep 6 (2016) 18544. doi: 10.1038/srep18544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Iwamiya T, Matsuura K, Masuda S, Shimizu T, Okano T, Cardiac fibroblast-derived VCAM-1 enhances cardiomyocyte proliferation for fabrication of bioengineered cardiac tissue, Regen. Ther 4 (2016) 92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.reth.2016.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Casper RC, Use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressants in pregnancy does carry risks, but the risks are small., J. Nerv. Ment. Dis 203 (2015) 167–9. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Bérard A, Zhao JP, Sheehy O, Antidepressant use during pregnancy and the risk of major congenital malformations in a cohort of depressed pregnant women: An updated analysis of the Quebec Pregnancy Cohort, BMJ Open. 7 (2017) e013372. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Satin J, Schroder EA, Autoregulation of Cardiac L-type calcium channels, Trends Cardiovasc. Med 19 (2009) 268–271. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Splawski I, Timothy KW, Decher N, Kumar P, Sachse FB, Beggs AH, Sanguinetti MC, Keating MT, Severe arrhythmia disorder caused by cardiac L-type calcium channel mutations, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 102 (2005) 8089–8096. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0502506102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Crespo LM, Grantham CJ, Cannell MB, Kinetics, stoichiometry and role of the Na-Ca exchange mechanism in isolated cardiac myocytes, Nature. 345 (1990) 618–621. doi: 10.1038/345618a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Lang D, Holzem K, Kang C, Xiao M, Hwang HJ, Ewald GA, Yamada KA, Efimov IR, Arrhythmogenic remodeling of β2 versus β1 adrenergic signaling in the human failing heart, Circ. Arrhythmia Electrophysiol 8 (2015) 409–419. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.114.002065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Junus K, Wikström AK, Larsson A, Olovsson M, Placental expression of proBNP/NT-proBNP and plasma levels of NT-proBNP in early- and late-onset preeclampsia, Am. J. Hypertens 27 (2014) 1225–1230. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Sadlecki P, Grabiec M, Walentowicz-Sadlecka M, Prenatal clinical assessment of NT-proBNP as a diagnostic tool for preeclampsia, gestational hypertension and gestational diabetes mellitus, PLoS One. 11 (2016) e0162957. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Kapoor A, Iqbal M, Petropoulos S, Ho HL, Gibb W, Matthews SG, Effects of Sertraline and Fluoxetine on P-Glycoprotein at Barrier Sites: In Vivo and In Vitro Approaches, PLoS One. 8 (2013) 3–8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Clabault H, Flipo D, Guibourdenche J, Fournier T, Sanderson JT, Vaillancourt C, Effects of selective serotonin-reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) on human villous trophoblasts syncytialization, Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol 349 (2018) 8–20. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2018.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kaufmann RL, Antoni H, Hennekes R, Jacob R, Kohlhardt M, Lab MJ, Mechanical response of the mammalian myocardium to modifications of the action potential, Cardiovasc. Res 5 (1971) 64–70. doi: 10.1093/cvr/5.supp1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]